Abstract

The search for stable compounds containing an antiaromatic cyclic 4π system is a challenge for inventive chemists that can look back on a long history. Here we report the isolation and characterization of the novel 4π-electron tetrasilacyclobutadiene, an analogue of a 4π neutral cyclobutadiene that exhibits surprising features of a Möbius-type aromatic ring. Reduction of RSiCl3 (R = (iPr)2PC6H4) with KC8 in the presence of cycloalkyl amino-carbene (cAAC) led to the formation of corresponding silylene 1. Compound 1 shows further reactivity when treated with RSiCl3 under reducing conditions resulting in the formation of unsymmetrical bis-silylene 2, which was isolated as a dark red crystalline solid. Compound 3 was obtained when chlorosilylene was reduced with potassium graphite in the presence of 2. Although 3 is, according to Hückel’s rule an antiaromatic system it possesses significant aromatic character due to the unusual delocalization of the HOMO-1 and the loss of degeneracy of the higher-lying π MOs. The aromatic character of 3 is indicated by the structural stability of the compound by the very similar Si-Si bond lengths and by the NICS values. There is an unusual π conjugation between the 4 π electrons in the nearly square-planar Si4 ring where the delocalization of the HOMO-1 occurs at two opposite sides of the ring. The reversal of the π conjugation resembles the twisting of the π conjugation in Möbius aromatic systems and it contributes to the stability of the compound.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aromaticity is a fundamental concept in chemistry whose understanding goes back to the pioneering work of Erich Hückel in 19311, who showed that the stability of cyclic π-conjugated molecules depends on the number of respective π-valence electrons in the molecules. It was later transformed in 1951 by Doering2 into the famous 4n + 2 rule for aromatic molecules, while antiaromatic species have 4n electrons. This rule still serves as a helpful guide to explain the particular stability of Hückel aromatic compounds not only for carbon species, but also for heteroatomic systems3. The reverse rule applies to Möbius aromatic compounds, where a sign reversal occurs in a twisted ring and the stabilizing interaction of the conjugated electrons arises on different sides of the ring. Such systems were theoretically proposed by Heilbronner in 19644, but the first isolated compound was only reported in 2003 by Herges5. Möbius aromatic compounds have 4n π electrons while Möbius antiaromatic molecules have 4n + 2 electrons. It should be noted that the specification of π electrons in twisted Möbius compounds is not strictly valid, as the molecules do not have a mirror plane. The notation of σ, π, δ, etc., introduced by Hund in 19276,7, refers to the symmetry of the molecular orbitals with respect to a mirror plane. The conjugated systems on Möbius systems actually have AO (atomic orbital) contributions which are not pure p orbitals. But the most important feature of a Möbius aromatic system is the rotation of the conjugation to the other side of the ring. This is important for the present work.

Much work has been devoted to the synthesis of Hückel antiaromatic 4π compounds, which are intrinsically unstable due to the degeneracy of the π2 and π3 orbitals shown for cyclobutadiene (Fig. 1)8,9. The degeneracy of the π orbitals can be resolved by the introduction of electron donor and electron acceptor substituents in the 1,3 and 2,4 positions of the ring. This strategy was used by Gompper10 who synthesized a push–pull stabilized cyclobutadiene with amino and nitrile substituents, which was spectroscopically identified but could not be isolated as a solid. The use of bulky substituents was more successful and several substituted cyclobutadienes could be synthesized and characterized by x-ray spectroscopy11,12. Recent advances have shown that the combination of heavier Group 14 elements in main group chemistry to form neutral and charged cyclobutadiene allows the fine-tuning of its stability and electronic structures by disrupting its aromatic and antiaromatic character13,14,15,16. Many heteroatom-containing four-membered rings with 4π electrons were successfully synthesized and isolated, and theoretical studies have also been carried out on a large scale to identify the electronic nature of such systems17,18,19. Nevertheless, there are only a handful of four-membered silicon rings with 4π electrons, which have a weak antiaromatic and aromatic character, that have been synthesized and studied by theoretical calculations. In 2011 Driess et al.20 and our group21 independently reported that the amidinate ligand stabilized 2,4-disila-1,3-diphosphacyclobutadiene has almost negligible antiaromaticity. The presence of amidinate ligands on the Si atoms contributes to the stabilization of the conjugated 4π electron system by increasing the energy difference between the occupied and unoccupied π MOs. In the same year, Inoue and Driess isolated the formal 4π-electron tetrasilacyclobutadiene dication A22. In the structure of A, the four-membered rhombic Si4 core is represented as a charge-localized structure with a disordered π-system, which is in contradiction to a classical Hückel antiaromatic system22,23. The delocalization is comparable to the dismutational aromaticity which was anticipated in the case of hexasilabenzene reported by Scheschkewitz24.

Very recently, a paper by Zhu, Cui, and coworkers25 appeared which reported the synthesis of a weakly aromatic 4π tetrasilacyclobutadiene compound (Fig. 2; B) with aryl and amidinate substituents which was used as a precursor for the isolation of saturated planar and puckered 2π tetrasilacyclobutane-1,3-diyls that show higher aromatic character than the 4π system25. Similar 4π tetrasilacyclobutadiene compounds were previously reported by So and co-workers (D)26 and by Suzuki et al. (C)27. The electronic structure in the Si4 ring was described in terms of cyclically delocalized n, π, σ electrons which yield moderate aromatic character although the systems are formally Hückel antiaromatic26.

We synthesized the related 4π tetrasilacyclobutadiene compound 3 with aryl and amidinate substituents (Fig. 2) and analyzed the electronic structure with a variety of methods. The bonding analysis showed that there is an unusual delocalization of the 4π-type electrons in the ring which resembles the situation in Möbius systems. This is suggested as the reason for the weak aromatic character of the ring and the stability of the compounds. The model may be used as a guideline for other systems where the proposed π stabilization is utilized to find related stable compounds.

Results and discussion

Reduction of RSiCl3 with potassium graphite in the presence of cycloalkyl amino-carbene (cAAC) at −80 °C to room temperature in THF resulting in the formation of a light-yellow coloured solution. After one-week light yellow block-shaped crystals of cAAC stabilized silylene RSi-Cl(cAAC) (1), (Scheme 1) were isolated with 70% yield at −30 °C from conc. solution of Et2O. Furthermore, the reduction of RSiCl3 with KC8 in the presence of crystalline 1 in 1:4:1 molar ratio in THF at −78 °C to room temperature afforded a red-coloured solution.

After two weeks red block-shaped crystals of a new type of unsymmetrical bis-silylene R(cAAC)Si-SiR (2) were obtained in 48% yield (Scheme 1) from Et2O at −30 °C, which incorporates an unprecedented five-membered ring where bis-silylene is stabilized by intramolecular phosphine and intermolecular cAAC carbene. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 1 and 2 are fully consistent with their formulation (Figs. S1–S9). The 31P NMR spectrum exhibits a sharp singlet at 8.99 ppm (for 1) and two sharp singlets at 1.67 and 38.13 ppm (for 2), attributed to free −P(iPr)2 and silylene coordinated Si-P(iPr)2 groups, respectively. Their 29Si NMR spectra exhibit one doublet resonance at δ 25.37 ppm (JSi-P = 46 Hz for 1), shifted downfield in comparison to chlorosilylene (δ 14.6), while 2 exhibits one doublet at 25.17 ppm (Si-cAAC; JSi-P = 31 Hz), and one singlet at −122.17 ppm (for Si-P), significantly shifted upfield compared to bis-silylene (δ 76.29)28,29. The difference in the chemical shift of compounds 1 and 2 could be due to the presence of free cAAC carbene ligands and slightly different ligands. The LIFDI mass spectra of 1 and 2 in toluene show ions at m/z 541.7 and 717.3, respectively, corresponding to the formation of RSi-Cl(cAAC) and R(cAAC)Si-SiR (Figs. S5 and S10). The UV–Vis spectrum of 1 in toluene shows an absorption band at 446 nm possibly due to n →π* excitation, while compound 2 exhibits a band at 430 nm possibly due to π→π* excitation (Fig. S16). Yellow-orange, block-shaped crystals suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction experiments (XRD) were obtained from a concentrated Et2O of 1 via slow evaporation. The compound crystallizes in the triclinic space group P\(\bar{{{{\boldsymbol{1}}}}}\) with one molecule in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 3).

The structural motif comprises one silicon atom in the centre, coordinated by a cAAC ligand, a chlorine atom, and the inserted group R(C6H4-PiPr2). The bond lengths of the Si-C bonds span from 1.848 to 1.910 Å, which is within the range of previously reported Si-C bond lengths30. Same applies for the C-Si-C angle, which is 108.83(7)° and therefore close to the ideal tetrahedron angle of 109.5°. This is also valid for the C9-Si-Cl angle, whose value is 109.36°. With a value of 100.39°, the C1-Si-Cl angle deviates the most from the ideal tetrahedron shape. Further, the Si1-Cl1 distance with a value of 2.172 Å correlates well with other already reported compounds containing a Si-Cl bond31. For 2, we obtained red block-shaped crystals suitable for XRD experiments from a saturated Et2O solution. In the asymmetric unit, one molecule is found, featuring the triclinic space group P\(\bar{{{{\boldsymbol{1}}}}}\). The two central silicon atoms together with one phosphorus and two carbon atoms form a five-membered ring. (Fig. 4). The corresponding Si-Si bond length is 2.367 Å and is in alignment with the expected silicon-silicon distance32,33. For P1-Si1 a bond length of 2.293 Å was determined, which fits well into the range of known bond lengths34,35. The angles C1-P1-Si1 (109.96(7)°) and C2-Si2-Si1 (106.61(7)°) are close to the ideal tetrahedral angle of 109.5°, while the P1-Si1-Si2 angle with a value of 85.38° is considerably smaller, thus showing a relatively high p-character36.

The most studied bis-silylene to date is the amidinate stabilized three-coordinated LSi-SiL (L = PhC(NtBu)2), which was reported by our group in 200937. Since that time, this compound has been employed in a remarkable array for the reductive activation of numerous p-block elements29,38. Fascinated by the reactivity of bis-silylene, we want to explore the reactivity of new unsymmetrical bis-silylene with highly reactive silylene39,40,41,42. Reaction of unsymmetrical bis-silylene with chlorosilylene (LSiCl) under reducing conditions in THF at −78 °C to room temperature resulted in the formation of a dark red-coloured solution. After two weeks reddish block-shaped crystals were obtained from Et2O solution at −30 °C which confirmed the formation of 4π-electron Si-containing four-membered ring (3). The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 3 are fully consistent with structural composition. 31P NMR spectrum of compound 3 exhibits a sharp singlet at 4.95 ppm illustrating the presence of a symmetrical pair of −P(iPr)2 groups (Fig. S13). Its 29Si NMR spectrum shows a doublet resonance at δ −93.71(JSi-P = 27 Hz) and a triplet at δ 51.31(JSi-P = 17 Hz), which are significantly shifted upfield and downfield compared to the reported Si4 ring (D; δ −70.8, 32.2)43 which is likely due to the different substituents. In compound D the substituted nitrogen atom is directly connected to the silylene of the ring causing a downfield shift (δ −70.8 ppm) compared to 3 (−93.71 ppm) and another silylene shows upfield shifting (δ 32.2 ppm) in comparison to 3 (51.31 ppm). The LIFDI mass spectrum of 3 in toluene shows an ion at m/z 717.3 corresponding to the formation of R2L2Si4 (Fig. S15) and the UV–Vis spectrum in toluene displays major absorption bands at 430 possibly due to π→π* excitation (Fig. S16). Single crystals of 3 (red, block-shaped) suitable for XRD were obtained from a concentrated Et2O solution. The compound crystallizes in monoclinic space group C2/c with half of a molecule in the asymmetric unit. Two symmetry-independent Si1 and Si2 silicon atoms, with a bond distance of 2.2792(4) Å, act as a building motif that expands via the presence of an inversion centre into a planar four-membered ring, creating an additional silicon-silicon bond with a bond length of 2.3018(4) Å (see Fig. 5). Angles Si1-Si2-Si1A and Si2-Si1-Si2A, where A stands for symmetry operation of 3/2-x,3/2-y,1-z, are 80.24(1)° and 99.76(1)°, respectively, and all torsion angles within the Si4 ring assembly are of 0°. All the structural features of this central moiety closely align with the recently published reports by So and co-workers43 and by Cui et al.25. In the asymmetric unit of compound 3 one can also observe another distinctive four-membered ring formed via Si1-N1-C5-N2 atoms. The ring is nearly planar with a torsion angle of 2.23(9)°. The N-Si bond lengths in the ligand backbone (1.8562(9)-1.862 Å) and the N-Si-N angle (70.40°) correlate well with other published similar complexes44,45,46.

The reaction mechanism for the formation of 3 from 2 and chlorosilylene (Scheme 1) is not known so far. It may involve the initial reduction of 2 with KC8 and the formation of a radical LSi• which then inserts into 2 and the dimerizes. Such a mechanism was suggested by So and co-workers for the formation of the related compound D (Chart 2)26.

Quantum chemical calculations

We carried out quantum chemical calculations using density functional theory with inclusion of dispersion interactions at the BP86 + D3(BJ)/def2-SVP level and we analyzed the electronic structures of the molecules to gain insight into the nature of the chemical bonds. Details of the theoretical methods are given in Supporting Information. The calculated equilibrium geometries of 1–3 are in very good agreement with the experimental data (Fig. S21). Table 1 shows the calculated NBO partial charges and the Mayer bond orders of the most important bonds. The results suggest that the cAAC ligands in 1–2 carry small negative charges, which indicates that they are stronger π acceptors than σ donors in these compounds. The Si atoms always have positive charges, but the size varies considerably between +1.01 e in 1 and only +0.01 for Si2 and Si2’ in 3, which can be explained by the nature of the respective substituents. The Mayer bond orders, which are more suitable for polar bonds than the Wiberg bond orders47, have values greater than 1 for the Si-cAAC bonds and support the notion of a significant Si→cAAC π-backdonation alongside the Si←cAAC σ-donation in compounds 1–2. This is further confirmed by the shape of the MOs. Figure S22 shows that the HOMO of 1–2 is a π-type orbital which describes the π interaction Si→cAAC. The Si-P bond orders in 1 (0.10) and 3 (0.13) are very small but they suggest some weak interactions, which is also indicated by the 29Si NMR spectrum which shows two signals with significant Si-P coupling constants.

The focus of the theoretical study is the analysis of the bonding situation in tetrasilacyclobutadiene 3. It deserves special attention because it has an unusual aromatic moiety. Compound 3 possesses a nearly planar cyclic 4π-electron system, which should be antiaromatic according to Hückel’s rule introduced by Doering4. But compound 3 can be isolated and structurally characterized by X-ray crystallography, which suggests that the Si-Si bonds in the four-membered ring are very similar.

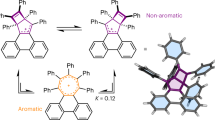

Figure 6a, b show the HOMO and HOMO-1 of 3, which illustrate the shape of the occupied π orbitals of the Si4 ring. The HOMO is a non-bonding MO localized at the three-coordinated Si2 and Si2A atoms. The shape of the AO contributions shows that they are spx hybridized orbitals with large 3 s character (59.6% s and 40.2% according to the NBO analysis) where the large lobes of the AOs are at opposite sides of the ring. The three substituents at the Si2 and Si2A atoms have a pyramidal arrangement, which leads to spx hybridized orbitals. The HOMO orbital of 3 resembles otherwise the π3 orbital of cyclobutadiene (Fig. 1). The hybridization of the AO contributions of the HOMO weakens the antibonding character of the orbital, because the overlap of the lobes with opposite sign on each side of the plane is reduced.

The energetically lower-lying HOMO-1 of 3 is a bonding MO delocalized over all four Si atoms which display an unusual pattern. The shape of the HOMO shows the same pattern as the π1 orbital of cyclobutadiene (Fig. 1) but there are peculiar differences due to the substituents. The Si1 and Si1A atoms are four-coordinated to the amidinate ligands which retain pure 3p AOs at silicon whereas the three-coordinated Si2 and Si2A atoms have a pyramidal arrangement. The shape of the HOMO-1 resembles two distorted allyl-like units with the largest delocalization of each fragment on the opposite side of the ring. There is a sign reversal of the sites with larger delocalization at Si1 and Si1A, which reminds of the sign reversal of Möbius aromatics introduced in 1964 by Heilbronner4 and realized for the first time in 2003 by Herges et al. 5. This is schematically shown in Fig. 6c. The delocalization of the HOMO-1 induces significant ring current, which comes to the fore by the calculated nucleus-independent chemical shift (NICS) values of NICS(0) = −9.1, NICSzz(−1) = −8.5, NICS(−1) = −5.9. The NICS values along with the chemical stability and the very similar Si-Si bond lengths suggest that 3 encounters significant aromatic stability due to the unusual π-delocalization of the HOMO-1. The higher-lying HOMO is not degenerate because of the very different substitution pattern at the silicon atoms.

We wish to emphasize that the reversal of charge delocalization exhibited by the HOMO-1 of 3 is not the same as the reversal of π conjugation in genuine Möbius systems, which comes from the twisting of the rings. Real Möbius aromaticity is only found in large cyclic systems where the graduate twist of the p(π) AOs leads to conjugative stabilization of 4π systems48,49,50. The π-type AOs of the Si atoms in 3 retain the same symmetry in the HOMO-1, but the hybridization of the spx AOs of Si2 and Si2A in opposite directions yields a reversal of the conjugation in a similar way. This is schematically shown in Fig. 6c, At the same time there is a strong hybridization of the spx AOs of Si2 and Si2A in the HOMO, which weakens its antibonding character. The two factors contribute to the shift from the antiaromatic character of the 4π Hückel system to a weakly aromatic 4π Möbius-type system, which is revealed by the NICS values for 3. Alternatively, one could consider the molecule as a doubly homoaromatic system where the unsaturated Si atoms Si2 and Si2A conjugate via the formally saturated Si atoms Si1 and Si1A. Since the π-interaction exhibits a reversal of the large area of conjugation to an opposite side of the ring, we consider a classification as a 4π Möbius system to be more appropriate. We readily acknowledge that the very unusual π interaction in 3 may be differently interpreted by other workers.

We calculated the vibrational spectrum of 3 and compared it with the experimental IR spectrum (Fig. S17). Unfortunately, the results are not very helpful for giving information about the Si-Si interactions, because the stretching modes are strongly coupled among each other and with the substituents. There are calculated vibrational modes at 611.7 cm−1, 529.4 cm−1 and 458.7 cm−1 which can clearly be assigned to the Si4 ring, with the second one having a very low IR intensity (see Table 2). The other two signals can be tentatively assigned to experimental vibrations, knowing that the calculated harmonic frequencies are usually a bit higher than the experimental anharmonic frequencies.

It is interesting to compare the bonding situation of the central Si4 moiety of 3 with previous studies of related compounds. The pioneering study by Matsuo, Tamao47 reported a cyclic Si4L4 compound (C, Fig. 2)) with four identical bulky ligands which built a planar rhombic structure with alternating planar and pyramidal configurations at the silicon atoms. The HOMO and HOMO-1 exhibit a similar pattern as in our compound, but the NICS value is only −0.9 ppm. The authors suggested that their Si4L4 compound is nonaromatic, because of a significant charge separation between the pyramidal Si atoms (q = 0.14 and 0.17 e) and planar Si atoms (q = 0.64 and 0.65 e)22. We found an even larger charge separation in our Si4L1L2 compound 3 between the pyramidal Si atoms (q = 0.01 e) and tetra-coordinated Si atoms (q = 0.94 e) but the NICS(1) value is −5.9 ppm. The Si4L1L2 compound (D, Fig. 1)43 with two three-coordinated and two tetra-coordinated Si atoms reported by So and co-workers is similar to our species 3. The authors did not report the atomic partial charges. The shape of the HOMO and HOMO-1 of their compound is similar to the HOMO and HOMO-1 of 3 with a notable difference of the HOMO-1, which is delocalized like a typical π orbital that extends to all four Si atoms without sign reversal of the largest part of the delocalization. This may be the reason that the NICS value of their compound is −10.1 ppm, comparable to benzene, which suggests an even higher degree of aromaticity than in 3.

A comparison of our results for compound 3 with the recent study by Zhu, Cui and coworkers is particularly interesting. The authors reported the synthesis, structural characterization and reactivity of several saturated tetrasilacyclubutane-1,3-diyls, which possess puckered equilibrium structures. One species adopts puckered and planar structures in the solid state. The analysis of the electronic structure suggested aromatic character and the molecules were introduced as 2π-aromatic system, which is a remarkable success. The authors reported also about the synthesis and bonding analysis of the tetrasilacyclobutadiene compound B, which is very similar to our compound 3. The authors noted that the HOMO of B is mainly composed of the lone-pair orbitals of the silicon atoms and that the HOMO-1 corresponds to a distorted π-type orbitals over the Si4 ring which makes the compound weakly aromatic. We think that they missed the unusual feature of Möbius-type aromaticity as shown in Fig. 6c, which leads to cyclic delocalization giving rise to significant magnetic anisotropy.

Summary and conclusion

In summary, we have succeeded in synthesizing a new highly reactive silylene which results in unsymmetrical bis-silylene 2 under reducing conditions. Compound 2 affords tetrasilacyclobutadiene 3 when treated with chlorosilylene under reducing conditions. Compound 3 exhibits an unusual π conjugation between 4π electrons in the nearly square-planar Si4 ring where the delocalization of the HOMO-1 occurs at two opposite sides of the ring. The reversal of the π conjugation resembles the twisting of the π conjugation in Möbius aromatic systems and it contributes to the stability of the compound.

Methods

All manipulations were carried out using standard Schlenk and glove box techniques under an atmosphere of high-purity dinitrogen. THF, hexane, and toluene were distilled over Na/K alloy (25:75), while diethyl ether was distilled over potassium mirror. Deuterated NMR solvents C6D6, C7D8, and THF-d8 were dried by stirring for 2 days over Na/K alloy followed by distillation in vacuum and degassed. 1H, 13C{1H} NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker Avance 200, Bruker Avance 300, and Bruker Avance 500 MHz NMR spectrometers and were referenced to the resonances of the solvent used. Microanalyses were performed by the Analytisches Labor für Anorganische Chemie der Universität Göttingen. Melting points were determined in sealed glass capillaries under dinitrogen and were uncorrected. LIFDI measurements were performed on a Joel AccuTOF spectrometer under an inert atmosphere, while all other reagents were used as received.

Synthesis of 1; [RSiCl(CAAc); R = C6H4P(iPr)2]

A mixture of RSiCl3 (335 mg, 1 mmol), cAAC (442 mg, 1 mmol), and KC8 (300 mg, 2.2 mmol) was taken in a 100 mL round bottom flask and 50 mL of THF was added at −80 °C. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature slowly and stirred until all the KC8 was consumed completely to give a yellow-coloured solution of compound 1. After solvent evaporation and filtration of insoluble residue, the Et2O solution was concentrated to 10 mL under reduced pressure. The flask was stored at 0 °C for 2 weeks to obtain X-ray quality yellow crystals of 1 (Yield: 378 mg, 70%), Mp: 205–210 °C.

1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6, 298 K, ppm): δ 0.91 (dd, 3 H, CHMe, J = 10 Hz), 1.04 (s, 3 H, CMe) 1.09 (dd, 3 H, CHMe, J = 5 Hz), 1.12 (s, 3 H, CMe3), 1.17 (dd, 6 H, CHMe2, J = 5 Hz), 1.24–1.25 (m, 6 H, CHMe2), 1.27 (d, 3 H, CHMe, J = 5 Hz), 1.57–1.60 (m, 5 H, CH2 & Me), 1.66 (d, 3 H, CHMe, J = 5 Hz), 1.77 (d, 3 H, CHMe, J = 5 Hz), 1.93 (sep, 1 H, CH), 2.15 (sep, 1 H, CH), 3.18 (sep, 1 H, CH), 3.29 (sep, 1 H, CH), 7.12–7.15 (m, 3 H, ArH), 7.19–7.23 (m, 2 H, ArH), 7.32–7.33 (m, 1 H, ArH), 8.20–8.22 (m, 1 H, ArH). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, C6D6, 298 K, ppm): δ 15.61, 19.04, 19.08, 20.02, 20.18, 20.80, 20.93, 23.93, 24.07, 24.51, 25.69, 25.75, 26.40, 26.54, 27.90, 28.20, 28.62, 29.78, 30.14, 31.03, 31.07, 32.64, 32.67, 49.58, 49.60, 55.16, 65.92, 67.83, 71.82, 124.24, 125.72, 128.35, 128.64, 129.03, 131.82, 131.83, 134.85, 141.03, 141.10, 143.96, 144.05, 148.59, 148.84, 154.31, 154.66, 195.48, 195.61. 31P{1H} NMR (202 MHz, C6D6, 298 K, ppm): δ 8.99. 29Si{1H} NMR (99 MHz, C6D6, 298 K, ppm): δ 25.37 (d, JSi-P = 46.53 Hz). Elemental analysis (%) calcd. for C32H51ClNPSi (541.32): C, 72.62; H, 9.45; N, 2.57; Found: C, 72.86; H, 9.23; N, 2.42; MS (LIFDI, toluene): m/z = 541.7 ([M+]+).

Synthesis of 2 [R(cAAC)Si-SiR

THF (50 mL) was added to a mixture of 1 (290 mg, 0.5 mmol), RSiCl3 (170 mg, 0.5 mmol), and KC8 (150 mg, 1.1 mmol) in a 100 mL round bottom flask at −80 °C. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature slowly to give a red-colored solution of compound 2. After solvent evaporation and filtration of insoluble residue, the Et2O solution was concentrated to 10–15 mL under reduced pressure. The flask was stored at 0 °C for 2 weeks to obtain X-ray quality red crystals of 2 (Yield: 174 mg, 48%); Mp: 192–200 °C.

1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6, 298 K, ppm): δ 0.63 (d, 3 H, CHMe, J = 5 Hz), 0.68 (dd, 3 H, CMe, J = 5 Hz) 0.77 (dd, 3 H, CHMe, J = 5 Hz), 1.02 (s, 3 H, CMe), 1.05–1.13 (dd, 6 H, CHMe2, J = 5 Hz), 1.17 (d, 3 H, CHMe, J = 5 Hz), 1.25 (s, 3 H, CMe), 1.26 (dd, 3 H, CHMe, J = 5 Hz), 1.31–1.33 (m, 5 H, CH2 & CHMe), 1.40–1.45 (m, 5 H, CH2 & CHMe), 1.47 (dd, 3 H, CHMe, J = 5 Hz), 1.77 (d, 3 H, CHMe, J = 5 Hz), 1.86 (s, 3 H, CHMe), 2.23 (sep, 1 H, CH), 2.26 (s, 3 H, CHMe), 2.40 (sep, 1 H, CH), 2.52 (sep, 1 H, CH), 3.34 (sep, 1 H, CH), 3.58 (sep, 2 H, CH), 5.23–5.25 (m, 1 H, ArH), 6.69–6.72 (m, 1 H, ArH), 6.74–6.77 (m, 1 H, ArH), 6.91–6.94 (m, 1 H, ArH), 6.99–7.02 (m, 2 H, ArH), 7.03–7.06 (m, 1 H, ArH), 7.24–7.26 (m, 2 H, ArH), 7.29–7.32 (m, 1 H, ArH), 8.72–8.74 (m, 1 H, ArH). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, C6D6, 298 K, ppm): δ 15.60, 17.53, 17.56, 17.68, 18.40, 18.77, 18.84, 19.99, 20.05, 20.44, 20.52, 20.54, 20.72, 21.15, 21.28, 22.27, 22.41, 24.36, 24.43, 24.51, 24.56, 25.07, 25.41, 25.81, 26.61, 26.88, 27.41, 27.55, 28.37, 28.58, 28.87, 29.50, 30.21, 32.94, 32.98, 37.46, 37.49, 48.88, 57.83, 65.92, 67.83, 67.88, 124.39, 124.44, 125.30, 125.92, 126.68, 126.71, 126.91, 128.35, 128.99, 130.09, 131.19, 131.49, 131.79, 135.86, 135.98, 139.90, 143.10, 143.13, 143.16, 143.20, 146.57, 146.61, 146.66, 146.70, 151.09, 152.21, 152.75, 152.79, 153.06, 153.09, 154.40, 154.43, 154.66, 154.68, 187.37, 187.44. 31P{1H} NMR (202 MHz, C6D6, 298 K, ppm): δ 1.67, 38.13. 29Si{1H} NMR (99 MHz, C6D6, 298 K, ppm): δ 25.17 (d, JSi-P = 31 Hz), 122.15. Elemental analysis (%) calcd. for C44H69NP2Si2 (727.43): C, 72.38; H, 9.53; N, 1.92; Found: C, 72.42; H, 9.39; N, 1.74; MS (LIFDI, toluene): m/z = 717.3 ([M-5H2]+).

Synthesis of 3 [R2L2Si4]

A mixture of PhC(NtBu)2SiCl (150 mg, 0.5 mmol), 2 (364 mg, 0.5 mmol), and KC8 (150 mg, 1.1 mmol) was placed in a 100 mL round bottom flask and 50 mL of THF was added at −80 °C. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature slowly and stirred at the same temperature until all the KC8 was consumed. After the evaporation of volatiles and filtration of insoluble residue, the Et2O solution was concentrated to 10 mL under reduced pressure. The flask was stored at −30 °C for two weeks to obtain X-ray quality red block-shaped crystals of 3 (Yield: 96 mg, 40%). Mp: Decomp. at 215 °C.

1H NMR (500 MHz, C7D8, 298 K, ppm): δ 1.25 (dd, 12 H, CHMe2, J = 5 Hz), 1.35 (dd, 12 H, CHMe2) 1.50 (s, 36 H, CMe3), 2.27 (sep, 4 H, CH), 7.02–7.05 (m, 8 H, ArH), 7.23–7.24 (m, 2 H, ArH), 7.54–7.55 (m, 4 H, ArH), 8.20–8.21 (m, 2 H, ArH). 13C NMR (126 MHz, C6D6, 298 K, ppm): δ 21.21, 21.31, 25.11, 25.24, 31.99, 55.27, 124.29, 125.39, 126.70, 127.84, 128.23, 129.16, 129.33, 129.71, 130.87, 134.17, 136.97, 137.06, 137.22, 137.46, 140.46, 140.54, 159.97, 160.34, 168.64. 31P{1H} NMR (202 MHz, C7D8, 298 K, ppm): δ 4.95. 29Si{1H} NMR (99 MHz, C7D8, 298 K, ppm): δ 51.31 (t, JSi-P = 17,82 Hz), −93.71 (d, JSi-P = 27,72 Hz). Elemental analysis (%) calcd. for C54H82N4P2Si4 (962.52): C, 67.31; H, 8.79; N, 5.81 Found: C, 67.13; H, 8.93; N, 5.67; MS (LIFDI, toluene): m/z = 717.3 ([M-PhC(tBuN)2Si + CH3]+).

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the authors upon request.

References

Hückel, E. Quantum-theoretical contributions to the benzene problem. I. The electron configuration of benzene and related compounds. Z. Phys. 70, 204–286 (1931).

Doering, Wv. E. & Detert, F. L. Synthesis of tropone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 73, 876–877 (1951).

Schleyer, P. R. For review articles about various aspects of aromaticity see the special issues entitled: “Introduction: Aromaticity” in Chem. Rev. 101, 1115–1118, (2001) and: “Introduction: Delocalization - pi and sigma” in Chem. Rev. 105, 3433–3435 (2005).

Heilbronner, E. Hűckel molecular orbitals of Mőbius-type conformations of annulenes. Tetrahedron Lett. 5, 1923–1928 (1964).

Ajami, D., Oeckler, O., Simon, A. & Herges, R. Synthesis of a Möbius aromatic hydrocarbon. Nature 426, 819–821, (2003).

Hund, F. Zur Frage der chemischen Bindung. Zeit. f. Phys. 73, 1 (1931).

Hund, F. Zur Frage der chemischen Bindung II. Zeit. f. Phys. 73, 565 (1932).

Maier, G. The cyclobutadiene problem. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 13, 425–438 (1974).

Sekiguchi, A., Tanaka, M., Matsuo, T. & Watanabe, H. From a cyclobutadiene dianion to a cyclobutadiene: synthesis and structural characterization of tetrasilyl-substituted cyclobutadiene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 40, 1675–1677 (2001).

Gompper, R. & SeyboId, G. A stable cylobutadiene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 7, 824 (1968).

Maier, G. Tetrahedrane and cyclobutadiene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 27, 824 (1988).

For a recent overview on antiaromaticity see: Karas, L. J., Wu, J. Antiaromatic compounds: a brief history, applications, and the many ways they escape antiaromaticity. in Aromaticity – Modern computational methods and application (ed. Fernandez, I.) 319–338 (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2021).

Lee, V. Y., Sekiguchi, A., Ichinohe, M. & Fukaya, N. Stable aromatic compounds containing heavier group 14 elements. J. Organomet. Chem. 611, 228–235 (2000).

Tokitoh, N. New progress in the chemistry of stable metallaaromatic compounds of heavier group 14 elements. Acc. Chem. Res. 37, 86–94 (2004).

Lee, V. Y. & Sekiguchi, A. Aromaticity of group 14 organometallics: experimental aspects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 6596–6620, (2007).

Yang, Y. F. et al. Silicon‐containing formal 4π‐electron four‐membered ring systems: antiaromatic, aromatic, or nonaromatic? Chem. Eur. J. 18, 7516–7524 (2012).

Canac, Y. et al. Isolation of a benzene valence isomer with one-electron phosphorus-phosphorus bonds. Science 279, 2080–2082 (1998).

Bertrand, G. Ylidic four π electron four‐membered λ5‐phosphorus heterocycles: electronical isomers of heterocyclobutadienes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 37, 270–281 (1998).

Ishida, Y., Donnadieu, B. & Bertrand, G. Stable four-π-electron, four-membered heterocyclic cations and carbenes. PNAS 103, 13585–13588 (2006).

Sen, S. S. et al. Zwitterionic SiK -C-Si-PL and SiK -P-Si-PL four-membered rings withtwo-coordinate phosphorus. At. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 2322–2325 (2011).

Inoue, S. et al. An ylide-like phosphasilene and striking formation of a 4π-electron, resonance-stabilized 2, 4-disila-1, 3-diphosphacyclobutadiene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 2868–2871, (2011).

Inoue, S., Epping, J. D., Irran, E. & Driess, M. Formation of a donor-stabilized tetrasilacyclobutadiene dication by a lewis acid assisted reaction of an N-heterocyclic chloro silylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 8514–8517 (2011).

Yang, Y.-F. et al. Silicon-containing formal 4π-electron four-membered ring systems: antiaromatic, aromatic, or nonaromatic? Chem. – Eur. J. 18, 7516–7524 (2012).

Abersfelder, K., White, A. J. P., Rzepa, H. S. & Scheschkewitz, D. A tricyclic aromatic isomer of hexasilabenzene. Science 327, 564–566 (2010).

Li, Y. et al. π-Aromaticity dominating in a saturated ring: neutral aromatic silicon analogues of cyclobutane-1,3-diyls. J. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.3c06555 (2023).

Zhang, S.-H., Xi, H.-W., Lim, K. H. & So, C.-W. An extensive n, π, σ-electron delocalized Si4 ring. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 12364–12367 (2013).

Suzuki, K. et al. A planar rhombic charge-separated tetrasilacyclobutadiene. Science 331, 1306–1309 (2011).

Sen, S. S., Khan, S., Nagendran, S. & Roesky, H. W. Interconnected bis-silylenes: a new dimension in organosilicon chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 578–587, (2012).

Ding, Y. et al. Stabilization of reactive nitrene by silylenes without using a reducing metal. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 27206–27211 (2021).

Pyykkö, P. Additive covalent radii for single-, double-, and triple-bonded molecules and tetrahedrally bonded crystals: a summary. J. Phys. Chem. 119, 2326–2337 (2015).

Hao, F.-Y., Su, R.-Z. & Cui, J.-G. Geometric structures and electron affinities of chlorine-doped silicon clusters. Mol. Phys. 108, 1919–1927 (2010).

Kyushin, S. et al. Silicon–silicon π single bond. Nat. Comm. 11, 4009 (2020).

Kern, T., Fischer, R., Flock, M. & Hassler, K. Synthesis and solid-state molecular structure of Bi(silacyclohexyls) C5H10SiX-XSiC5H10 with X = H, PH, F, CL, BR, and I. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 188, 931–940 (2013).

Seitz, A. E. et al. Different reactivity of As4 towards disilenes and silylenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 6655–6659 (2017).

Pyykkö, P. & Atsumi, M. Molecular single-bond covalent radii for elements 1–118. Chem. Eur. J. 15, 186–197 (2009).

Hartmann, M. et al. Synthesis, characterisation and complexation of phosphino disilenes. Dalton Trans. 39, 9288–9295, (2010).

Sen, S. S., Jana, A., Roesky, H. W. & Schulzke, C. A remarkable base-stabilized Bis(silylene) with a Silicon(I)–Silicon(I) Bond. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 8536–8538 (2009).

Nazish, M. et al. Compounds with alternating single and double bonds of antimony and silicon; Isoelectronic to Ethane-1,2-diimine. Inorg. Chem. 62, 9306–9313 (2023).

Nazish, M. et al. Coordination and stabilization of a lithium ion with a silylene. Chem. Eur. J. 29, e202203528 (2023).

Nazish, M. et al. Excellent yield of a variety of silicon-boron radicals and their reactivity. Dalton Trans. 51, 11040–11047 (2022).

Nazish, M. et al. Synthesis and coordination behavior of a new hybrid bidentate ligand with phosphine and silylene donors. Chem. Eur. J. 27, 1744–1752 (2021).

Nazish, M. et al. A neutral borylene and its conversion to a radical by selective hydrogen transfer. Inorg. Chem. 62, 9343–9349 (2023).

Azhakar, R., Ghadwal, R. S., Roesky, H. W., Hey, J. & Stalke, D. Facile access to transition‐Metal–Carbonyl complexes with an amidinate‐stabilized chlorosilylene ligand. Chem. Asian J. 7, 528–533, (2012).

Li, J. et al. Reactions of amidinate-supported silylene with organoboron dihalides. Inorg. Chem. 59, 7910–7914 (2020).

Jana, A. et al. Reactions of stable amidinate chlorosilylene and [1+4]-oxidative addition of N-heterocyclic silylene with N-benzylideneaniline. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 5006–5013 (2011).

von, E., Doering, W. & Detert, F. L. Cycloheptatrienylium oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 73, 876–877 (1951).

Zhao, L., Pan, S., Wang, G. & Frenking, G. The nature of the polar covalent bond. J. Chem. Phys. 157, 034105 (2022).

Szysko, B., Sprutta, N., Chwalisz, P., Stepien, M. & Latos-Grazynski, L. Hückel and Möbius expanded para-benziporphyrins: synthesis and aromaticity switching. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 1985–1997 (2014).

Rzepa, H. Linking number analysis of a pentadecanuclear metallamacrocycle: a Möbius-Craig system revealed. Inorg. Chem. 47, 8932–8943 (2008).

Stepien, M., Latos-Grazynski, L., Sprutta, N., Chwalisz, P. & Szterenberg, L. Expanded porphyrin with a split personality: a Hückel–Möbius aromaticity switch. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 7869–7873 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to Prof. Christian Reichardt on the occasion of his 90th birthday. L.Z. and G.F. acknowledge financial support from Nanjing Tech University (No. 39837123, 39837132, and the International Cooperation), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22373050), Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu province (BK20211587), the State Key Laboratory of Material-Oriented Chemical Engineering (SKL-MCE-23A06), and computational support from the high-performance centre of Nanjing Tech University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.N. and A.K. designed the project and carried out the experiments and analyzed the data. M.N., A.K., and G.F. wrote the manuscript. H.W.R. designed the project and helped in the analysis of the data and preparation of the manuscript. Y.H., L.Z., and G.F. performed computational studies. T.P. and A.K. performed and refined the crystallographic part. S.K.K. performed the Raman and IR spectroscopic work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nazish, M., Patten, T., Huang, Y. et al. Neutral 4π-electron tetrasilacyclobutadiene contains unusual features of a Möbius-type aromatic ring. Commun Chem 7, 307 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-024-01396-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-024-01396-9