Abstract

While it has been long supposed that asteroids played a role in the delivery of important prebiotic compounds to early Earth, the exact nature of the interactions between asteroidal material and metabolism remains largely unquantified. Pristine material from asteroid sample-return missions provides an unprecedented opportunity to evaluate the potential for the asteroids’ chemistry to support the origin and persistence of life. Here we use metabolic network expansion to computationally test the viability of contrasted biochemical networks, including a group of acetogens and methanogens representing primitive metabolisms, on the known chemistry of three asteroids (Itokawa, Ryugu, Bennu) and two meteorites (Murchison, Murray). The chemistry of Murchison and Bennu appears to support the potential viability of the acetogenic and methanogenic metabolisms. In contrast, Murray, Ryugu and Itokawa samples lack critical substrates, particularly adenine and D-ribose needed for ATP production, suggesting that carbonaceous bodies vary in their compositional capacity to support the acetogenic and methanogenic metabolisms. This highlights the astrobiological relevance of asteroids rich in carbon, nitrogen, and phosphate such as Bennu, and hints at the habitability, past or present, of their parent bodies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The delivery of chemical compounds important to prebiotic chemistry to the early Earth has long been a topic of interest in astrobiology, particularly the introduction of simple organic compounds from primitive asteroids by meteorite impact1,2. A critical question is to what extent compounds present in primitive bodies formed during the early evolution of the Solar System—which could then provide meteoritic material to Earth—could support the metabolic function of life as we know it. Are these primitive compounds sufficient to support metabolisms that are thought to be present on the early Earth? If not, what compounds might be missing? The recent returns and in-depth analyses of pristine asteroid samples provide a unique opportunity to answer these questions3,4,5.

Contemporary cellular life is driven by metabolic networks that are composed of hundreds of enzymatic species and reactions. However, only a subset of key chemical species from the environment is needed as input to these networks to deliver the full complement of enzymes that underlie cell maintenance, growth, and division. This is essentially because, given the available compounds, new products resulting from functional reactions may become substrates that fuel other reactions. The key question, as stated by Smith et al.6, then is ”whether or not a given biochemical system (organism or ecosystem) could, in principle, produce the compounds necessary for its survival from environmentally available compounds”. In other words, does the chemical environment contain a minimal set of compounds needed for a biochemical network to produce its full enzymatic complement? With a positive answer, the corresponding metabolism is deemed ”potentially viable” in that chemical environment. We should note that this definition does not necessarily take into account the thermodynamic favorability of the enzymatic reactions, though these factors are discussed in other works7,8,9,10,11. In addition, it is assumed that requisite compounds are available in sufficiently high concentrations for the enzymatic reactions to take place, but not so high that there is a risk of “poisoning” the networks.

The network expansion approach developed by Handorf et al.12 provides a computational pipeline to answer this question. Our goal is to apply this approach to the known chemical composition of asteroid samples and of carbonaceous meteorites for comparison. Specifically, the analysis of samples recently returned from the B-type asteroid 101955 (Bennu) by the Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, and Security-Regolith Explorer mission (OSIRIS-REx) adds to the short list of directly collected asteroid samples (from C-type 162,173 Ryugu and S-type 25,143 Itokawa) and data from meteorites, which altogether provide a unique opportunity to assess the potential for primitive material chemistry to deliver to Earth the compounds needed for metabolic viability on a planetary surface—or even to have sustained metabolism on the primordial parent bodies of these asteroids during the early solar system.

B-type asteroid Bennu and C-type asteroid Ryugu share many key chemical features with CM carbonaceous chondrites, especially in hydration, organics, and primitive composition; they also represent less altered, more pristine records of early solar system materials13. Bennu may be more similar to CI chondrites (like Orgueil) in bulk chemistry but resembles CM in hydration. Ryugu samples show less altered fragments than typical CM chondrites. The Bennu and Ryugu asteroids may reflect different depths or regions of CM-like parent bodies or multiple parent bodies14.

In addition to chemical data from Bennu, Ryugu, and Itokawa samples, we consider the CM2 chondrites Murchison and Murray. Having some of the richest chemical inventories among meteorites, with relatively high concentrations of organic materials and hydrated minerals, CM2 chondrites are outstanding candidates to test the ability of asteroidal material to supply compounds required for primitive metabolic viability to an aqueous, early Earth environment.

Following the network expansion approach12, environmentally available compounds are used as a ”seed set” for the reactions of a metabolic network, which may characterize a single species, a metabolic guild, or a more complex ecological system. The network expansion algorithm then determines the set of all possible reaction products, called the “scope” of the seed set. The potential viability of the organism, metabolic guild, or ecological system in that environment is defined by comparing the scope of the seed set with the “target set” of the metabolic network. The target set may include all compounds known to be used in the biochemistry of the organism or ecological system of interest, or it may be a distilled list, such as the 66 metabolites identified by Freilich et al.15 as essential for terrestrial life as a whole. In turn, the potential metabolic viability thus evaluated provides a qualitative assessment of the chemical habitability of the environment. As we pointed out earlier, and echoing6, we re-emphasize that network expansion provides a minimum criterion for metabolic viability and environmental habitability, which ignores other basic environmental factors such as temperature, pH or salinity, as well as kinetic and thermodynamic constraints on metabolic rates and biomass production. These limitations will be addressed further in the discussion.

To better understand how the compounds available in an environment could support or limit metabolic function, we use network expansion to construct a ”reverse ecology” of metabolisms based on the genomic data that describe these metabolisms16,17. We implement this approach in three stages. First, as a proof of concept, we apply and validate the method using a bacterium species known to form an isolated single-species ecosystem. The species, Candidatus Desulforudis audaxviator, is a chemoautotroph that was isolated from a rock fracture 2.8 km below the surface in a South African gold mine18. The detailed description of its metabolism and chemical environment makes it an ideal example for testing the network expansion approach. The expectation is that the predicted species’ seed set is entirely contained in the environmental chemical inventory.

Next, we focus on two metabolic guilds that may have played a key role in the emergence of primitive ecosystems: anaerobic acetogenic bacteria and methanogenic archaea. Phylogenetic analyses have placed acetogenesis and methanogenesis among the earliest metabolisms, with recent studies supporting the claim that LUCA was acetogenic19,20. Acetogenesis and methanogenesis are thus natural candidates for assessing the potential viability of primitive metabolisms on a chemical environment shaped by meteoritic delivery. Finally, for comparison, we determine the seed set of the metabolic network that represents the total biosphere. Rather than focusing on the wide possible scope of biochemical products that can be produced by compounding all known biochemistry, our objective is to target the 66 compounds identified by Freilich et al.15 as critical to terrestrial biology (Table 1).

The seed sets of the acetogenic and methanogenic guilds can be compared with the known chemical composition of asteroid samples and meteorites. A sample containing a full seed set would indicate a chemical environment whose composition might support the corresponding metabolism. A sample lacking some of the compounds in the acetogenic or methanogenic seed sets but containing all compounds of the biosphere metabolic seed set would indicate a chemical environment whose composition might support the metabolism of an ecological network of metabolic complexity intermediate between our two endmember biologies—the putatively primitive acetagonesis and methanogenesis, and the whole modern biosphere (Fig. 1).

A Metabolic network and seed set of the bacterium Candidatus Desulforudis audaxviator, which forms a single-species ecosystem in a deep-underground isolated environment. The metabolic network is composed of 615 nodes and 2577 edges. The initial seed set contains 94 nodes, comprised of 26 compounds and 68 generic species (see “Methods” for more details). B Combined network of the 11 acetogenic bacterial species examined, composed of 1289 nodes and 5278 edges. Note that this combined network is different from the individual-species networks that we subject to network expansion (see “Methods”). C Metabolic network of the total biosphere, composed of 8954 nodes and 34,583 edges. Networks were constructed by querying the KEGG database for the reactants and products of every reaction in a species' reaction list, which were then converted into nodes, and the reactions themselves were assigned as edges. The resulting graph was then visualized using Cytoscape99.

Results

Network expansion requires a seed set of compounds, which are then reacted with a given group of enzymes, the products of which are then added back to the seed set, and the process is repeated until no new products can be produced. The identification of the minimum seed sets required to produce the entire metabolic network of the organisms under consideration was a primary goal of this study.

In all cases, we find the seed sets to include elemental sources of the basic compounds of terrestrial life (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur), as well as a varying mix of trace elements. These trace elements include manganese (crucial in a vast array of enzymes, particularly those involving redox reactions21), zinc (involved in many enzymes and transcription factors22), iron (a central component of iron–sulfur proteins and heme proteins23), calcium (used in enzymes and signal transduction pathways)24), magnesium (critical to stabilizing polyphosphate bonds, e.g., ATP25), sodium (plays a key role in transport systems26), cobalt (central component of cobalamin and other enzymes27), selenium (utilized via the amino acid selenocysteine28) and molybdenum (used in several enzymes, particularly nitrogenases29) as well as other metals that play roles in specific metabolisms, e.g., nickel (an essential component to the enzymes used in methanogenesis30). While these findings are purely qualitative, as the network expansion algorithm used does not account for minimum and maximum concentrations, it nonetheless offers insight into the necessary conditions of terrestrial biochemistry, particularly in regard to the need for simple organics.

Testbed: single-species ecosystem

The single-species ecosystem formed by D. audaxviator provides a unique opportunity to test and validate the network expansion approach. In multi-species ecosystems, chemical substrates needed by any species may be the metabolic product of another species, thus potentially causing a spurious reduction in the apparent seed set of the focal species. We were able to determine the minimal seed set of D. audaxviator required to synthesize the organism’s entire biochemical scope (Table 2). All compounds in this seed set are available in the organism’s environment18. Moreover, the metabolic network of D. audaxviator is able to produce 65 out of 66 compounds essential to terrestrial biochemistry out of the predicted seed set (see Table 1). The only compound missing, ubiquinone, is not a compound used in D. audaxviator’s metabolism, explaining its absence.

This demonstrates that the chemical environment needed for metabolic viability can be inferred by network expansion and successfully matched with the known chemical environment. Interestingly, there is a notable degree of redundancy in terms of inorganic substrates for several vital elements—sulfur, for example, must be present in two different forms (sulfate and hydrogen sulfide) in order for D. audaxviator to synthesize the entirety of its biochemical scope. While D. audaxviator possesses the enzymes necessary to reduce sulfate to hydrogen sulfide, synthesizing the necessary co-reactants itself requires the presence of hydrogen sulfide. Thus, the presence of hydrogen sulfide allows this pathway to be ‘bootstrapped’ into functionality. While D. audaxviator was not able to produce its full scope using meteoritic material as a seed set due to the redundancy mentioned above, it was able to produce all compounds essential to terrestrial biochemistry (see Table 1).

Potential viability of acetogens and methanogens

The minimal seed set required to synthesize 100% of the biochemical scope of the acetogen and methanogen species (Table 3) are similar to that of D. audaxviator, but with a few salient differences: the acetogens do not require as diverse an array of inorganic substrates in terms of iron, sulfur, and selenium, and the methanogens require even fewer inorganic substrates. This is in line with the fact that the environment of acetogen species is generally less metal-rich than that of D. audaxviator. Like D. audaxviator, the acetogens and methanogens both require the presence of d-ribose and adenine to produce ATP (but see ref. 31 for a discussion of the shortfalls of the KEGG database in this respect).

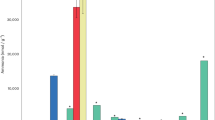

We then surveyed the literature to determine whether the members of these seed sets could be found in the asteroids and meteorites chemical inventories (Table 3). All required compounds are present in Murchison. The chemistry of the Bennu asteroid can support the acetogen networks and the methanogen networks, though in the case of the former, species in the order of Eubacteriales would not be viable, due to the apparent absence of sulfite, which has yet to be reported on Bennu. Sulfide minerals, however, have been reported32, and, assuming that these minerals would give rise to hydrogen sulfide when reacting with water, would provide a sulfur source for the methanogens. Chemical seeds that are critical for the potential viability of acetogenic and methanogenic networks are missing from Murray, Itokawa, and Ryugu (Table 3).

The functional consequences of the chemical deficiencies of Murray, Itokawa, and Ryugu compared to the seed sets of primitive metabolisms (acetogens and methanogens) become apparent when considering the ability of the corresponding metabolic networks to generate the 66 signature compounds of biochemistry (see Table 1). While sufficiently complex ecosystems would produce all or almost all of them from the seed compounds present in any of the five meteorites and asteroids tested here, the acetogenic or methanogenic networks on Murray, Itokawa, and Ryugu would generate no more than twelve of these signature compounds, all amino acids. In contrast, acetogenic and methanogenic networks generate very similar biochemical complements on Murchison and Bennu, which comprise almost all 66 signature compounds. The acetogenic network expansions only miss heme O and ubiquinone, consistent with the fact that these are primarily used by eukaryotes.

Potential viability of the total biosphere

Using the entirety of known enzymes, we determined the minimum seed set required to produce the 66 essential compounds of Earth total biochemistry (see Table 1). To this end, we initiated the selection process with the primitive prebiotic seed set used by Goldford et al.33 and sequentially removed substrates from the seed set until the expansion algorithm was no longer able to produce one or more of the 66 essential compounds. The resulting minimal seed set is composed of carbon (in inorganic and organic forms), ammonia, orthophosphate, sulfate, and an array of trace metals and inorganic cofactors (see tick marks in Seed Set column of Table 3).

All members of the minimal seed set exist in the asteroids Ryugu and Bennu, as well as in the Murchison and Murray meteorites (Table 3). A seed set based on Itokawa was less successful, as it was able to generate only 55 of the 66 essential compounds by the total biosphere (see Table 1). This was due to the lack of a source of sulfur, which prevented the synthesis of the amino acids cysteine, methionine, and their derivatives; this sulfur depletion is believed to be the result of partial melting of the asteroid’s parent body34 and/or space weathering35.

Discussion

The network expansion approach provides a first test of the potential viability of a metabolic network in a given chemical environment. Applying this approach to the bacterial extremophile D. audaxviator, which forms a deep-surface isolated single-species ecosystem, supports the validity of the method. Network expansion of acetogenic and methanogenic metabolisms in the chemical environment of CM chondrites Murchison and Murray, S-type asteroid Itokawa, C-type asteroid Ryugu, and B-type asteroid Bennu, yields contrasting results. A key finding is that the acetogenic and methanogenic guilds analyzed here are potentially metabolically viable on the chemistry of Murchison and Bennu. In contrast, both Murray and Ryugu samples lack substrates that are critical to the viability of acetogens and methanogens and the production of the essential compounds of Earth's biochemistry. Itokawa, which belongs to a different class of asteroids (silica-rich rather than carbon-rich), shows even more severe deficiencies for the viability of acetogenic and methanogenic metabolisms.

Murchison and Murray are CM chondrites, which are rich in carbon and hydrated minerals. While Murchison contains the full seed sets required for the metabolic viability of tested acetogens and methanogens, the Murray meteorite is lacking five key compounds required by the acetogenic and methanogenic metabolisms: pyruvate (an organic carbon source), sodium and molybdenum (inorganic cofactors), and adenine and D-ribose, necessary for bootstrapping ATP production. Indeed, while Murray is known to contain simple organic compounds, pyruvate does not appear to be among them36. The sodium cofactor has been detected in the Murray meteorite, but its abundance is much lower compared to similar meteorites, including Murchison, possibly due to post-fall leaching37,38. The analysis of molybdenum in Murray is poorly constrained, only inferred from the detection of presolar grains, such as silicon carbide (SiC), which are known to contain trace amounts of molybdenum. Direct isotopic analyses of molybdenum in Murray are limited, and most detailed studies have focused on other CM2 chondrites like Murchison. These studies suggest that molybdenum exists in various forms in meteorites, yet the specific identification of molybdate ions remains rare overall (e.g., refs. 39,40,41). As for adenine and D-ribose, one may not fully exclude that their relative molecular instability could have caused their degradation over time or during sample collection and analysis.

In terms of primitive metabolic viability, samples from Bennu turn out to be similar to Murchison in that they contain the full seed sets of acetogens and methanogens. In comparison, samples of asteroid Ryugu and Itokawa lack several compounds from the acetogen and methanogen seed sets. Of two key organic carbon sources, pyruvate and 2-oxoglutarate (both central intermediates in the Krebs cycle), only pyruvate was detected in Ryugu42. Extensive studies have identified a variety of organic compounds in Ryugu’s samples, including amino acids, aliphatic amines, carboxylic acids, and nucleobases like uracil; yet the specific detection of 2-oxoglutarate has not been reported.

Ryugu and Itokawa are also poor in nitrogen sources. The nitrogen content in Ryugu’s insoluble organic matter is lower than that found in certain meteorites43. Even though micrometer-sized NH-rich organic compounds, including amine-related molecules44, have been identified in some Ryugu particles, overall the S-rich composition of the Ryugu samples contrasts with the N-rich chemistry of Bennu45. On Itokawa, nitrogen exists in the form of polyaromatic carbon46), but ammonium as a nitrogen source is lacking.

Itokawa belongs to the family of S-type (silica-rich) asteroids, which are known to be carbon-poor. Although both inorganic and organic carbon have been reported from Itokawa samples, they occur in forms (graphite and disordered polyaromatic carbon) that may not seed metabolic reactions and suggest a complex thermal history of the asteroid’s parent body, including significant thermal metamorphism with heating possibly exceeding 800 °C47. This process may also have caused volatile elements like Zn to evaporate. Similar depletion of volatile elements (including zinc) has been documented in highly metamorphosed meteorites (such as type 6 ordinary chondrites). In addition to zinc, Itokawa lacks selenium as a critical inorganic factor.

d-ribose and adenine, which are present in Murchison and Bennu48,49 samples but lack in Murray, Itokawa, and Ryugu, turn out to be essential for the potential viability of primitive metabolisms (Table 3). This is clearly indicated by the similarly dramatic reduction of essential biochemistry compounds produced by acetogenic and methanogenic networks on Murray, Itokawa, and Ryugu chemistry alike (Table 3). There are other critical seeds missing specifically in each of these bodies for the viability of acetogens and methanogens, but the similar reduction of essential compounds across all three suggests that the deficiency in adenine and D-ribose is chiefly responsible. Even though d-ribose and adenine are not required to bootstrap production of ATP when all terrestrial enzymatic reactions are available, de novo synthesis is not possible until after 14 iteration of network expansion (out of a total of 38), suggesting that the pathway is not easily accessible by simpler biochemistry. This strongly suggests that LUCA and other early forms of life made use of adenine and d-ribose to synthesize ATP. The alternative of abiotic ATP synthesis50,51, in which case life would only later have gained the ability to produce it de novo, may not be excluded, however.

On a more conceptual note, we re-emphasize that the network expansion analysis is a purely qualitative approach to metabolic viability that does not account for kinetic or thermodynamic constraints and how these constraints are shaped or influenced by substrate and product quantities as well as environmental conditions (e.g., local temperature, pH, salinity). Taking these constraints into account would require explicit dynamical modeling of metabolic reactions, cell population growth, and environmental feedbacks, as was done for methanogenic or acetogenic metabolisms in highly simplified chemical environments of early Earth surface ocean9, Enceladus interior ocean52, and Mars subsurface brines53. In future research, these models could be adapted to use the full seed sets as inventories of environmental resources, capture the dynamics of substrates and products with general kinetic and thermodynamic laws, and quantitatively evaluate the habitability of the asteroid or parent body’s environment for the metabolisms under consideration.

Conclusion

The presence of the minimal seed sets for acetogenic and methanogenic metabolisms on Murchison and Bennu lends support to the potential importance of carbonaceous meteorites in the promotion of prebiotic and transition to biotic chemistry on the early Earth2,54, and also explains why terrestrial bacteria were able to colonize contaminated samples so quickly once given the opportunity55. The detection of adenine and D-ribose in Murchison and Bennu points to the possibility that these compounds could have been available in their parent bodies and that meteorites may have delivered them to early Earth. While adenine and D-ribose may have been elusive in Ryugu samples due to limited mass available for analysis, their absence in the Murray meteorite indicates that such compounds may not be uniformly distributed across all carbon-rich bodies. With mounting evidence of hydrothermal alteration of asteroids56,57,58, as well as the fact that even in the current day, some asteroids (including Bennu) show signs of activity and volatile outgassing59,60, and, in the case of Ceres, may possess a subsurface ocean61,62, our results highlight the value of furthering the astrobiological investigation of asteroids. Indeed, the potential metabolic viability of asteroid chemistry is a first hint at the possible habitability, past or present, of the parent bodies.

Methods

Network expansion starts with a seed set of compounds. The algorithm searches the KEGG database of enzymatic pathways known to terrestrial biology to determine what compounds can be formed using the seed set as available substrates. Enzymes can be restricted to only those that appear in a specific organism, or all enzymes known can be used. The new compounds produced by these pathways are then added to the seed set as potential substrates for the enzymatic pathways, and the process is repeated, producing further new compounds. This continues iteratively until it is no longer possible to produce new compounds. This method allows us to quickly explore the metabolic space accessible to terrestrial biology, given the available substrates in an environment.

Single-species ecosystem: Candidatus Desulforudis audaxviator

To perform network expansion on D. audaxviator, we first needed to determine what biochemical reactions it could facilitate as an organism. To find this information, we used the Bio.KEGG package from BioPython63 to query the KEGG database. The KEGG database includes the annotated genome of D. audaxviator, categorizing its genes in terms of the metabolic pathways the gene products participate in (e.g., the pathway dau00010 includes all genes associated with glycolysis and gluconeogenesis). The enzymes among these products are bundled with the reaction(s) they catalyze; each reaction is assigned a unique reaction ID (RID) by KEGG (e.g., R00299 is the RID for the reaction catalyzed ATP:d-glucose 6-phosphotransferase, which transfers a phosphate group onto a glucose molecule).

The reactions are used as the basis of the network expansion algorithm, as mentioned above. However, due to the presence of incomplete or not-yet-characterized pathways64, some modification of the reaction list was required, either by adding reactions or removing them.

Reactions were added for three reasons (see Table S1). First, if the missing reaction was required for the biosynthesis pathway for a biomolecule that is known to be essential to all terrestrial life (e.g., thiamine), it was added back to the list, since the organism would simply not be able to survive without it.

Second, if the pathway was otherwise complete and only missing one or two enzymatic steps, it was reasoned that it was unlikely that D. audaxviator would have evolutionary pressure to otherwise maintain the rest of the entire pathway, and therefore the missing reaction must be being performed using an equivalent unknown enzyme or pathway.

Lastly, in the case of cobalamin, D. audaxviator is known to synthesize the compound65, and the compound plays an important role in organisms living in similar deep subsurface environments66, even though it seemingly lacks the ability to produce many of the known enzymes required for cobalamin biosynthesis. Nonetheless, these reactions must be occurring within the organism, and so the necessary reactions were added to the reaction set.

Reactions were removed under several conditions (see Table S2). First, reactions were judged to be “side reactions” if they were the result of an enzyme’s specificity to multiple substrates. For example, D. audaxviator possesses a gene for the production of the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase, which plays multiple roles in the metabolism of carbon compounds. However, it can also catalyze the degradation of 1-hydroxymethylnaphthalene, and consequently, KEGG included this reaction in the reaction list—but since D. audaxviator completely lacks the rest of the metabolic pathways necessary for the degradation of naphthalene, this reaction was judged as very unlikely to occur, and thus removed.

In addition, some enzymes of high substrate specificity were seemingly missing the rest of the pathway they belonged to. For example, D. audaxviator possesses a gene corresponding to the coenzyme B:coenzyme M:methanophenazine oxidoreductase and its associated reaction R04540, but lacks the genes required to synthesize coenzyme B and coenzyme M. This may be the result of a pseudogene or of the rest of the pathway being facilitated by unknown enzymes, and, in light of such uncertainty, the reaction was removed.

Finally, several reactions were categorized as “generic”, and were included by KEGG to illustrate a class of reactions. As these reactions, by their nature, did not correspond to reactions involving specific compounds, they were removed as extraneous.

The seed set was determined by starting first with the seed set developed by Goldford et al.33, and then sequentially adding or removing compounds until the minimum set required to generate the entire biochemical scope of the organism, within the constraints of its environment. In addition to compounds available in its environment18, a number of other compounds were added (see Table S3). The majority of these compounds were “generics”–compounds listed in KEGG that represent an entire class of compounds. For example, compound C00161, 2-oxo acid, is a generic compound that represents any alpha-keto acids, such as pyruvic acid, oxaloacetic acid, or alpha-ketoglutaric acid. Due to their generic nature, KEGG does not include a formation pathway for them, and they must be included in the seed set in order for reactions that use them to function.

Adenine and ribose were also included–while there is a de novo biosynthesis pathway for both of them, many of the enzymes in their pathways require the presence of ATP, itself a derivative of adenine and ribose, and KEGG currently lacks a straightforward pathway for its synthesis31. Thus, without access to a much larger range of enzymes, it is difficult to make these precursors without already having them, and its presence is required to ‘bootstrap’ the metabolic network of the organism.

From the results of the BioXP network expansion, we were in turn able to determine the minimal seed set of compounds required to generate the entire scope of D. audaxviator’s metabolic scope.

Primitive metabolic guild: acetogens and methanogens

To determine the seed set of acetogens and methanogens as a class, we queried the KEGG database for the genomes and reaction lists of 13 anaerobic acetogens and 9 methanogenic archaea. We focused primarily on organisms found in the ambient environment (as opposed to gut flora), as this seemed more likely to resemble a putative acetogenic LUCA20.

As a first-pass analysis, we fed the reaction list of each species through NetSeed, a Perl script written to identify the seed set of a biochemical network67. The resulting seed sets were then fed into BioXP and adjusted until we found a single seed set that the network expansion algorithm was able to generate at least ≈ 100% of the biochemical scope of all 11 acetogen species; we then repeated this process to find a single seed set that could generate at least ≈ 100% of the biochemical scope of all 9 methanogen species.

These adjustments included removing extraneous species and adding KEGG’s generic compounds when there was no pathway in the KEGG database to produce them (see Tables S4 and S5 in the SI). In addition, four compounds–(2S)-2-Phospholactate, pimelate, methanofuran, and 7,8-dihydromethanopterin–were added to the seed set of the methanogens, as KEGG appears to lack complete synthesis pathways for these compounds. Finally, as was the case with D. audaxviator, adenine and D-ribose were added to both the seed sets of the acetogens and the methanogens to bootstrap ATP production.

In addition, like D. audaxviator, reactions were added or removed to more realistically model the biochemical networks of the organisms. 25 reactions were added to all acetogens (see Table S6), and 15 were removed (see Table S7).

To the methanogens, 51 reactions were added (see Table S8); this higher number is likely a result of the genomes and pathways of archaea being less well-characterized compared to bacteria and eukaryotes68; in particular, folate synthesis pathways were included, as Archaea are known to make use of folate equivalents even if the exact pathway is not well understood69. Eight reactions were removed (see Table S9), six of which were all part of the same incomplete metabolic pathway.

Further reactions were added and removed on a species-by-species basis (see Tables S11–32 for acetogens and Tables S33–50 for methanogens in the SI).

Total biosphere

Based on the analysis of the metabolic networks of 447 organisms in the KEGG database70,71, 66 specific compounds are present in 90% of the organism-specific networks, suggesting that these compounds are essential for terrestrial biochemistry to sustain itself12,72 (see Table 1). However, it should be noted that any given organism is not guaranteed to use all 66 compounds; for example, ubiquinone is largely restricted to eukaryotes and the phylum Pseudomonadota of bacteria73, and heme O is predominantly associated with aerobes74. This is particularly true for the methanogens, which, being archaea, produce ether-linked lipids instead of ester-linked lipid compounds, and therefore do not need many of the intermediates required for glycerophospholipid production.

Some reactions in KEGG were removed from those available to terrestrial biochemistry, due to being elementally unbalanced stoichiometrically31–that is, an element is present on the left side of the reaction equation, but not the right side (see Table S10). For example, R09158 in the KEGG database is listed as CO2 → C2HCl3O2, seemingly generating a chlorine and hydrogen atom from nowhere in violation of the laws of physics, necessitating its removal.

We then determined the minimal seed set required to produce all 66 of these compounds via BioXP, using the minimal seed set found for D. audaxviator as a starting point, and BioXP being able to use all enzymatic pathways in the KEGG database. We then removed compounds until the minimal set was found.

Data availability

Data are available at https://github.com/tessarion87/AE_NetworkExpansion.

Code availability

Code is available at https://github.com/tessarion87/AE_NetworkExpansion.

References

Pizzarello, S. Chemical evolution and meteorites: an update. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 34, 25–34 (2004).

Pizzarello, S. Prebiotic chemical evolution: a meteoritic perspective. Rendiconti Lincei 22, 153–163 (2011).

Parker, E. T., Chan, Q. H., Glavin, D. P. & Dworkin, J. P. Non-protein amino acids identified in carbon-rich hayabusa particles. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 57, 776–793 (2022).

Naraoka, H. et al. Soluble organic molecules in samples of the carbonaceous asteroid (162173) Ryugu. Science 379, eabn9033 (2023).

Lauretta, D. S. et al. Asteroid (101955) Bennu in the laboratory: properties of the sample collected by OSIRIS-REx. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 59, 2453–2486 (2024).

Smith, H. B., Drew, A., Malloy, J. F. & Walker, S. I. Seeding biochemistry on other worlds: Enceladus as a case study. Astrobiology 21, 177–190 (2021).

Nisbet, E. & Sleep, N. The habitat and nature of early life. Nature 409, 1083–1091 (2001).

Moore, E. K., Jelen, B. I., Giovannelli, D., Raanan, H. & Falkowski, P. G. Metal availability and the expanding network of microbial metabolisms in the Archaean eon. Nat. Geosci. 10, 629–636 (2017).

Sauterey, B., Charnay, B., Affholder, A., Mazevet, S. & Ferrière, R. Co-evolution of primitive methane-cycling ecosystems and early Earth’s atmosphere and climate. Nat. Commun. 11, 2705 (2020).

Chatterjee, S. Bioenergetics and primitive metabolism. In From Stardust to First Cells: The Origin and Evolution of Early Life, 67–74 (Springer, 2023).

Lyons, T. W. et al. Co-evolution of early Earth environments and microbial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 22, 572–586 (2024).

Handorf, T., Ebenhöh, O. & Heinrich, R. Expanding metabolic networks: scopes of compounds, robustness, and evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 61, 498–512 (2005).

Grady, M. M. et al. Overview of the findings for samples returned from Ryugu and implications for early solar system processes. Nat. Astron. 9, 1–6 (2025).

Barosch, J. et al. Presolar stardust in asteroid Ryugu. Astrophys. J. Lett. 935, L3 (2022).

Freilich, S. et al. Metabolic-network-driven analysis of bacterial ecological strategies. Genome Biol. 10, 1–8 (2009).

Borenstein, E., Kupiec, M., Feldman, M. W. & Ruppin, E. Large-scale reconstruction and phylogenetic analysis of metabolic environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 14482–14487 (2008).

Levy, R. & Borenstein, E. Reverse ecology: from systems to environments and back. In Evolutionary Systems Biology, (ed. Soyer, O. S.) 329–345 (Springer, 2012).

Chivian, D. et al. Environmental genomics reveals a single-species ecosystem deep within Earth. Science 322, 275–278 (2008).

Schwander, L. et al. Serpentinization as the source of energy, electrons, organics, catalysts, nutrients and pH gradients for the origin of LUCA and life. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1257597 (2023).

Moody, E. R. et al. The nature of the last universal common ancestor and its impact on the early Earth system. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 1654–1666 (2024).

Rice, D. B., Massie, A. A. & Jackson, T. A. Manganese–oxygen intermediates in o–o bond activation and hydrogen-atom transfer reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 2706–2717 (2017).

Maret, W. Zinc biochemistry: from a single zinc enzyme to a key element of life. Adv. Nutr. 4, 82–91 (2013).

Crichton, R. R. & Boelaert, J. R. Inorganic Biochemistry of Iron Metabolism: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Consequences (John Wiley & Sons, 2001).

Brini, M., Ottolini, D., Calì, T. & Carafoli, E. Calcium in health and disease. In Interrelations Between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases (eds. Sigel, A. Sigel, H. & Sigel, R.K.O.) 81–137 (Springer, 2013).

Wolf, F. I. & Cittadini, A. Chemistry and biochemistry of magnesium. Mol. Asp. Med. 24, 3–9 (2003).

Dimroth, P. Mechanisms of sodium transport in bacteria. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B, Biol. Sci. 326, 465–477 (1990).

Okamoto, S. & Eltis, L. D. The biological occurrence and trafficking of cobalt. Metallomics 3, 963–970 (2011).

Wendel, A. Biochemical functions of selenium. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 67, 405–415 (1992).

Mendel, R. R. & Bittner, F. Cell biology of molybdenum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 1763, 621–635 (2006).

Ragsdale, S. W. Nickel biochemistry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2, 208–215 (1998).

Slocombe, L., Millsaps, C., Narasimhan, K. & Walker, S. CBRdb: a curated biochemical reaction database for precise biochemical reaction analysis. https://chemrxiv.org/engage/chemrxiv/article-details/67c28c046dde43c908f7aa37 (2025).

Zega, T. J. et al. Mineralogical evidence for hydrothermal alteration of bennu samples. Nat. Geosci. 18, 832–839 (2025).

Goldford, J. E., Smith, H. B., Longo, L. M., Wing, B. A. & McGlynn, S. E. Primitive purine biosynthesis connects ancient geochemistry to modern metabolism. Nat. Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.07.511356v2 (2024).

Arai, T. et al. Sulfur abundance of asteroid 25143 Itokawa observed by X-ray fluorescence spectrometer onboard Hayabusa. Earth Planets Space 60, 21–31 (2008).

Matsumoto, T., Harries, D., Langenhorst, F., Miyake, A. & Noguchi, T. Iron whiskers on asteroid Itokawa indicate sulfide destruction by space weathering. Nat. Commun. 11, 1117 (2020).

Cooper, G., Reed, C., Nguyen, D., Carter, M. & Wang, Y. Detection and formation scenario of citric acid, pyruvic acid, and other possible metabolism precursors in carbonaceous meteorites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14015–14020 (2011).

Kallemeyn, G. W. & Wasson, J. T. The compositional classification of chondrites—I. the carbonaceous chondrite groups. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 45, 1217–1230 (1981).

Huss, G. R., Meshik, A. P., Smith, J. B. & Hohenberg, C. Presolar diamond, silicon carbide, and graphite in carbonaceous chondrites: implications for thermal processing in the solar nebula. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 4823–4848 (2003).

Dauphas, N., Marty, B. & Reisberg, L. Molybdenum evidence for inherited planetary scale isotope heterogeneity of the protosolar nebula. Astrophys. J. 565, 640 (2002).

Yin, Q., Jacobsen, S. B. & Yamashita, K. Diverse supernova sources of pre-solar material inferred from molybdenum isotopes in meteorites. Nature 415, 881–883 (2002).

Burkhardt, C. et al. Molybdenum isotope anomalies in meteorites: constraints on solar nebula evolution and origin of the Earth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 312, 390–400 (2011).

Takano, Y. et al. Primordial aqueous alteration recorded in water-soluble organic molecules from the carbonaceous asteroid (162173) Ryugu. Nat. Commun. 15, 5708 (2024).

Quirico, E. et al. Compositional heterogeneity of insoluble organic matter extracted from asteroid Ryugu samples. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 59, 1907–1924 (2024).

Vacher, L. et al. Amides from the carbonaceous asteroid (162173) Ryugu: Nanoscale spectral and isotopic characterizations. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 60, 2033–2051 (2025).

Glavin, D. P. et al. Abundant ammonia and nitrogen-rich soluble organic matter in samples from asteroid (101955) Bennu. Nat. Astron. 9, 199–210 (2025).

Chan, Q. et al. Organic matter and water from asteroid Itokawa. Sci. Rep. 11, 5125 (2021).

Burgess, K. & Stroud, R. Comparison of space weathering features in three particles from Itokawa. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 56, 1109–1124 (2021).

Furukawa, Y. et al. Extraterrestrial ribose and other sugars in primitive meteorites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 24440–24445 (2019).

Furukawa, Y. et al. Bio-essential sugars in samples from asteroid (101955) Bennu. Nat. Geosci. 19, 19–24 (2025).

Chu, X.-Y. & Zhang, H.-Y. Prebiotic synthesis of ATP: a terrestrial volcanism-dependent pathway. Life 13, 731 (2023).

Pinna, S. et al. A prebiotic basis for ATP as the universal energy currency. PLoS Biol. 20, e3001437 (2022).

Affholder, A., Guyot, F., Sauterey, B., Ferrière, R. & Mazevet, S. Bayesian analysis of Enceladus’s plume data to assess methanogenesis. Nat. Astron. 5, 805–814 (2021).

Sauterey, B., Charnay, B., Affholder, A., Mazevet, S. & Ferrière, R. Early Mars habitability and global cooling by H2-based methanogens. Nat. Astron. 6, 1263–1271 (2022).

Chimiak, L. et al. Carbon isotope evidence for the substrates and mechanisms of prebiotic synthesis in the early solar system. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 292, 188–202 (2021).

Genge, M. J. et al. Rapid colonization of a space-returned Ryugu sample by terrestrial microorganisms. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 60, 64–73 (2024).

Dyl, K. A. et al. Early solar system hydrothermal activity in chondritic asteroids on 1–10-year timescales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 18306–18311 (2012).

Che, S. & Zega, T. J. Hydrothermal fluid activity on asteroid Itokawa. Nat. Astron. 7, 1063–1069 (2023).

McCoy, T. J. et al. An evaporite sequence from ancient brine recorded in Bennu samples. Nature 637, 1072–1077 (2025).

Jewitt, D. The active asteroids. Astron. J. 143, 66 (2012).

Lauretta, D. et al. Episodes of particle ejection from the surface of the active asteroid (101955) Bennu. Science 366, eaay3544 (2019).

Castillo-Rogez, J. C. et al. Ceres: astrobiological target and possible ocean world. Astrobiology 20, 269–291 (2020).

Castillo-Rogez, J. Future exploration of Ceres as an ocean world. Nat. Astron. 4, 732–734 (2020).

Cock, P. J. et al. Biopython: freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 25, 1422 (2009).

Kanehisa, M. et al. Data, information, knowledge and principle: back to metabolism in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D199–D205 (2014).

Jungbluth, S. P., Del Rio, T. G., Tringe, S. G., Stepanauskas, R. & Rappé, M. S. Genomic comparisons of a bacterial lineage that inhabits both marine and terrestrial deep subsurface systems. PeerJ 5, e3134 (2017).

Mateos, G., Martínez-Bonilla, A., Martínez, J. M. & Amils, R. Vitamin B12 auxotrophy in isolates from the deep subsurface of the Iberian Pyrite Belt. Genes 14, 1339 (2023).

Carr, R. & Borenstein, E. Netseed: a network-based reverse-ecology tool for calculating the metabolic interface of an organism with its environment. Bioinformatics 28, 734–735 (2012).

Makarova, K. S., Wolf, Y. I. & Koonin, E. V. Towards functional characterization of archaeal genomic dark matter. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 47, 389–398 (2019).

White, R. H. Purine biosynthesis in the domain archaea without folates or modified folates. J. Bacteriol. 179, 3374–3377 (1997).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. et al. From genomics to chemical genomics: new developments in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D354–D357 (2006).

Handorf, T., Christian, N., Ebenhöh, O. & Kahn, D. An environmental perspective on metabolism. J. Theor. Biol. 252, 530–537 (2008).

Nowicka, B. & Kruk, J. Occurrence, biosynthesis and function of isoprenoid quinones. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenerg. 1797, 1587–1605 (2010).

Rivett, E. D., Dang, M. A. & Hegg, E. L. Heme o isolation and analysis using heme o synthase heterologously expressed. In Escherichia coli. In Iron Metabolism: Methods and Protocols, (ed. Khalimonchuk, O.) 131–149 (Springer, 2024).

Pizzarello, S., Feng, X., Epstein, S. & Cronin, J. R. Isotopic analyses of nitrogenous compounds from the Murchison meteorite: ammonia, amines, amino acids, and polar hydrocarbons. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58, 5579–5587 (1994).

Cooper, G. W., Onwo, W. M. & Cronin, J. R. Alkyl phosphonic acids and sulfonic acids in the Murchison meteorite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 4109–4115 (1992).

Zhu, C. et al. Space weathering-induced formation of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and hydrogen disulfide (H2S2) in the Murchison meteorite. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 124, 2772–2779 (2019).

Huang, S. & Jacobsen, S. B. Calcium isotopic compositions of chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 201, 364–376 (2017).

Bouvier, A., Wadhwa, M., Simon, S. B. & Grossman, L. Magnesium isotopic fractionation in chondrules from the Murchison and Murray cm 2 carbonaceous chondrites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 48, 339–353 (2013).

Nichiporuk, W. & Moore, C. B. Lithium, sodium and potassium abundances in carbonaceous chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 38, 1691–1701 (1974).

Koga, T., Takano, Y., Oba, Y., Naraoka, H. & Ohkouchi, N. Abundant extraterrestrial purine nucleobases in the Murchison meteorite: Implications for a unified mechanism for purine synthesis in carbonaceous chondrite parent bodies. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 365, 253–265 (2024).

Martins, Z., Alexander, C. O., Orzechowska, G., Fogel, M. & Ehrenfreund, P. Indigenous amino acids in primitive cr meteorites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 42, 2125–2136 (2007).

Hayes, J. M. & Biemann, K. High resolution mass spectrometric investigations of the organic constituents of the Murray and Holbrook chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 32, 239–267 (1968).

Krähenbühl, U., Morgan, J. W., Ganapathy, R. & Anders, E. Abundance of 17 trace elements in carbonaceous chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 37, 1353–1370 (1973).

Lee, M. R. & Greenwood, R. C. Alteration of calcium-and aluminium-rich inclusions in the Murray (cm2) carbonaceous chondrite. Meteoritics 29, 780–790 (1994).

Nichiporuk, W., Chodos, A., Helin, E. & Brown, H. Determination of iron, nickel, cobalt, calcium, chromium and manganese in stony meteorites by X-ray fluorescence. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 31, 1911–1930 (1967).

Kadlag, Y. & Becker, H. Highly siderophile and chalcogen element constraints on the origin of components of the Allende and Murchison meteorites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 51, 1136–1152 (2016).

Ebihara, M. et al. Neutron activation analysis of a particle returned from asteroid Itokawa. Science 333, 1119–1121 (2011).

Nakamura, T. et al. Itokawa dust particles: a direct link between s-type asteroids and ordinary chondrites. Science 333, 1113–1116 (2011).

Yamaguchi, A. et al. Insight into multi-step geological evolution of c-type asteroids from Ryugu particles. Nat. Astron. 7, 398–405 (2023).

Yokoyama, T. et al. Samples returned from the asteroid Ryugu are similar to Ivuna-type carbonaceous meteorites. Science 379, eabn7850 (2022).

Hessel, V. et al. Continuous-flow extraction of adjacent metals—a disruptive economic window for in situ resource utilization of asteroids? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 3368–3388 (2021).

Nakamura, T. et al. Formation and evolution of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu: direct evidence from returned samples. Science 379, eabn8671 (2022).

Nakanishi, N. et al. Nucleosynthetic s-process depletion in mo from Ryugu samples returned by Hayabusa2. Geochem. Perspect. Lett. 28, 31–36 (2023).

Yoshimura, T. et al. Chemical evolution of primordial salts and organic sulfur molecules in the asteroid 162173 Ryugu. Nat. Commun. 14, 5284 (2023).

Pilorget, C. et al. Phosphorus-rich grains in Ryugu samples with major biochemical potential. Nat. Astron. 8, 1529–1535 (2024).

Bazi, B. et al. Trace-element analysis of mineral grains in Ryugu rock fragment sections by synchrotron-based confocal X-ray fluorescence. Earth Planets Space 74, 161 (2022).

Bizzarro, M. et al. The magnesium isotope composition of samples returned from asteroid Ryugu. Astrophys. J. Lett. 958, L25 (2023).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504 (2003).

Acknowledgements

We thank Harrison Smith for his assistance in using BioXP and Dante Lauretta for sharing unpublished results from the chemical analysis of 101955 Bennu samples and allowing us to use them in our analysis. This work was funded by the United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Interdisciplinary Consortium for Astrobiology Research program (award number 80NSSC21K059). R.F. acknowledges additional support from the US National Science Foundation, Biology Integration Institute-Implementation (award number DBI-2022070), Growing Convergence in Research (award number OIA-2121155), and National Research Traineeship (award number DGE-2022055) programmes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.F. conceived the research. T.F. collected the metabolic and chemical data, performed the network expansion analysis of the metabolic networks, collated and organized the results, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. R.F. edited and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Raphael Plasson and Yamei Li for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fisher, T., Ferriere, R. Potential metabolic viability on asteroid chemistry. Commun Chem 9, 54 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01860-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01860-0