Abstract

Non-Hermitian systems have been shown to have a dramatic sensitivity to their boundary conditions. In particular, the non-Hermitian skin effect induces collective boundary localization upon turning off boundary coupling, a feature very distinct from that under periodic boundary conditions. Here we develop a full framework for non-Hermitian impurity physics in a non-reciprocal lattice, with periodic/open boundary conditions and even their interpolations being special cases across a whole range of boundary impurity strengths. We uncover steady states with scale-free localization along or even against the direction of non-reciprocity in various impurity strength regimes. Also present are Bloch-like states that survive albeit broken translational invariance. We further explore the co-existence of non-Hermitian skin effect and scale-free localization, where even qualitative aspects of the system’s spectrum can be extremely sensitive to impurity strength. Specific circuit setups are also proposed for experimentally detecting the scale-free accumulation, with simulation results confirming our main findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spatial inhomogeneity in physical systems is the norm rather than the exception. It can trigger a wide variety of physical phenomena, such as the Anderson localization, topological edge states, and topological defect states. In non-Hermitian systems, intriguing physics from spatial inhomogeneity encompasses not just the non-Hermitian skin effect (NHSE)1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29, but also impurity-induced or defect-induced topological bound states30,31,32,33, disorder-driven non-Hermitian topological phase transitions34, as well as non-Hermitian quasi-crystals and mobility edges with an incommensurate modulation35,36,37,38.

Due to their emergent non-locality, non-reciprocal impurities in non-Hermitian systems generate dramatic spectral flows as their strengths are varied3,39,40. This has even been proposed for exponentially enhanced quantum sensing in an experimentally realistic setting41,42. Since most of conventional condensed matter studies have been based on the assumption of locality, this non-locality can challenge usual notions of wavefunction decay, such as the relationship between scale-free behavior and criticality. Besides, there does not exist a full framework for non-Hermitian impurity physics, with periodic and open boundary conditions (PBCs and OBCs) being special cases across a whole range of boundary impurity strengths. This work aims to fill in this important gap and reports unexpected findings of general theoretical and experimental interest.

Specifically, we discover that boundary impurities in non-reciprocal lattices can generate new types of steady-state localization behavior characterized by scale-free accumulation (SFA) of eigenstates, despite having non-power-law profile. This enigmatic behavior is possible because the correlation length does not have a fixed value but scales with the system size, despite the system being not critical. In sharp contrast to the NHSE, the SFA direction can be counter-intuitive, opposite of the non-reciprocal directionality. With varying impurity strengths, the steady state makes transitions between the NHSE behavior, Bloch-like eigenstates with broken translational invariance, ordinary SFA, and reversed SFA. A careful inspection of these qualitatively rich transitions reveals fascinating duality relations between weak and strong inhomogeneities, yielding a big picture of non-Hermitian impurity physics. Known NHSE properties are thus revealed as only one of the many impurity-induced consequences in non-reciprocal non-Hermitian systems. Drastically different steady-state behaviors can even co-exist when next-nearest hoppings are present, a useful phenomenon that can benchmark the hyper-sensitivity of non-Hermitian systems to boundary/impurity effects due to their emergent non-locality.

Results

Impurity-induced SFA

We consider impurities in the simplest 1D Hatano–Nelson chain43, which already exhibits nearly the full scope of impurity-induced phenomena in more generic lattices. An impurity is represented as a modified coupling between the first and last sites:

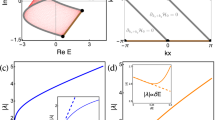

with μ± = μe±α, μ controlling the local impurity, α > 0 and x = 0, 1, . . ., L labeling the lattice sites (Fig. 1a). Physics of impurity in a non-Hermitian lattice was also studied in ref. 33. However, ref. 33 investigated a topological nontrivial lattice with on-site impurity, with a focus on the few topological edge modes isolated from the continuous bands. Of central interest here is the impact of hopping impurity on the bulk eigenmodes. Because of our setting, PBCs are recovered at μ = 1, where translational symmetry is restored and the system can be described by a Bloch Hamiltonian H(z) = eαz + e−α/z with z = eik, k the quasi-momentum. Perfect OBCs yielding the NHSE are recovered at μ = 0, although a finite-size system behaves like OBCs when μ ≲ e−α(L+1)26,40. Cases with 0 < μ < 1 may be interpreted as interpolations between PBCs and OBCs, but a full picture with new physics emerges only if the whole range of 0 < μ < ∞ is investigated. Beyond μ ∈ [0, 1], eigenstates can exhibit weaker boundary accumulation toward either direction, even unexpectedly against the direction of non-reciprocity and NHSE (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, this intriguing localization phenomenon is dubbed the SFA because the eigenstates display a scale-free spatial profile, decaying as e−Cx/L with constant C, as elaborated later. Unlike in the NHSE, the spectrum of these SFA eigenstates forms a loop that can be deformed away from, or even enclosing the PBC spectrum (Fig. 1c). Different accumulation regimes exist for μ ranging from 0 to ∞, and notably similar behaviors are seen in both the small and large μ limits (Fig. 1d). As detailed in our concrete examples later, we find two types of dualities between μ and ~1/μ, which allow us to probe the large μ regime from the small μ regime, and vice versa.

a The Hatano–Nelson model with x = 0, 1, 2, . . ., L the number of lattice sites, e±α the non-reciprocal nearest-neighbor couplings, and impurity couplings μe±α between the sites 0 and L. Periodic and open boundary conditions (PBCs and OBCs) correspond to μ = 1 and 0, respectively, but other μ support qualitatively different phenomena. b Spatial eigenstate distributions ρ(x) = ∣ψx∣2 with different accumulating behaviors (normal and reversed scale-free accumulations, and the non-Hermitian skin effect (NHSE)), with ψx the wave-function value at x. c Complex spectra with \({\rm{Re}}[E]\) and \({\rm{Im}}[E]\) the real and imaginary parts of the energies, distinguishing the four types of eigenstates in (b). d Different regimes across the whole range μ are marked by different accumulation phenomena, with dualities relating strong and weak μ.

Ordinary and reversed SFA

To understand why SFA occurs, we analytically solve for the eigenstates \({{{\Psi }}}_{n}=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{x}^{L}{\psi }_{x,n}{\hat{c}}_{x}^{\dagger }\left|0\right\rangle\), n = 0, . . . , L via HΨn = EnΨn, under reasonable approximations. In the large-μ limit with μ ≫ e±α, two isolated eigenstates strongly localize at x = 0, L, with eigenenergies Eiso ≈ ±μ (see the “Methods” section). The other eigenstates are exponentially decaying:

with ψ0,n ≈ 0 (see the “Methods” section], n = 1, 2, . . . , L−1 yielding L−1 different eigenstates. These L−1 eigenstates have the common decay constant κL. Physically, the vanishing amplitude at x = 0 can be partially appreciated by the physics underlying electromagnetic field-induced transparency44. That is, the much stronger coupling between sites L and 0 effectively makes the rest of the lattice more “transparent”, and hence suppresses the population pumping from the rest of the lattice to site 0. In a more restricted parameter regime with eα ≫ e−α and μ ≪ eα(L+1), the corresponding eigenenergies can be further approximated by

with kn := (2n + 1)π/(L−1) and ϵ(k) the eigenenergy function at μ = 1 (i.e. PBCs) (see the “Methods” section). Remarkably, here the spectrum is obtainable via a complex deformation of the PBC quasi-momentum, similar to the approach of generalized Brillouin zone (GBZ) for OBC systems1,2,3, yielding an exponential decay profile of the eigenstates. Yet, the associated decay exponent κL in Eq. (1) is inversely proportional to the size of the lattice, namely, \({\kappa }_{L}\propto \frac{1}{L-1}\approx \frac{1}{L}\), indicating weaker accumulation for a larger system. In fact, because of this, the overall decay of the eigenstates from one end of the lattice to the other end, given by ∣ψL,n/ψ1,n∣ = e2α/μ, is independent of L, thus giving rise to a scale-free decay profile from x = 1 to L. The dependence of κL on μ (and L) also differs from that of impurity-induced topological localization (see Supplementary Note 1 and Fig. 1).

Counter-intuitively, reversed accumulation with negative κL can occur when μ < e2α, which still falls into a valid sub-regime if μ ≫ eα ≫ e−α, as confirmed by the agreement between our approximate solutions and numerical results in Fig. 2a. For the peculiar borderline case of μ = e2α between ordinary and reversed SFA, κL = 0 and the eigenstates are uniformly distributed (except at x = 0) and hence resemble Bloch states [Eq. (1) and Fig. 2a], even though translational invariance is broken. Indeed, the continuous part of the associated spectrum also coincides with the PBC spectrum [Eq. (2) and Fig 2b]. This curious case of quasi-PBC delocalized states is elaborated in the “Methods” section. While we have considered a strong non-reciprocity of α = 4 in Fig. 2 for a better illustration, more examples with weaker α are found in Supplementary Note 2 and Fig. 2.

a Average distribution of all the anomalously accumulating eigenstates \(\bar{\rho }(x)=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{n = 1}^{L-1}{\rho }_{n}(x)/(L-1)\) with ρn(x) = ∣ψx,n∣2, ψx,n the wave-function value of the nth eigenstate at x, and α = 4, L = 20. The blue, orange, and green cases correspond to reversed scale-free accumulation (SFA), quasi-periodic boundary conditions (PBCs) and SFA. b Spectra for these anomalously accumulating eigenstates, excluding the two isolated eigenstates induced by the strong impurity. The black dashed curve is the true PBC spectrum (μ = 1), which overlaps with the quasi-PBC orange curve at μ = e2α = e8. In both panels, the circles, squares, and triangles are numerical data points, and the colored solid curves are approximations from Eqs. (1) and (2).

Duality between strong and weak impurity couplings

The discussions above imply a duality between PBCs at μ = 1 and quasi-PBCs at μ = e2α. This motivates us to seek duality relations for the whole range of μ. For e−2α ≪ μ ≪ 1, another set of exponentially decaying eigenfunctions are found, i.e.,

with

provided that eα ≫ e−α, where \({k}_{n}^{\prime}:=2n\pi /(L+1)\) (see the “Methods” section of the weak impurity). Taking κL and \({\kappa }_{L}^{\prime}\) as functions of μ, we have \({\kappa }_{L}(\mu )\approx {\kappa }_{L}^{\prime}({e}^{2\alpha }/\mu )\) for a sufficiently large system, suggesting a duality between \(\mu ={\mu }_{\alpha }^{\pm }\) with \({\mu }_{\alpha }^{\pm }={e}^{\alpha }{A}^{\pm 1}\) parametrized by a variable A, with \({\mu }_{\alpha }^{+}={\mu }_{\alpha }^{-}\) at A = 1.

This duality can be seen in both the spectrum and the eigenstate accumulation, which can be characterized by the inverse participation ratio (IPR) defined as In = ∑x∣ψx,n∣4 for a given eigenstate. The IPR approaches 1 for a perfectly localized state, and 1/(L + 1) for a spatially homogeneous one. To further characterize the different directions of the SFA states, we define a directed IPR as Id,n = ∑x(xc − x)∣ψx,n∣4/(L/2), with xc = L/2 being the center of the system. By definition, Id takes positive (negative) values for states accumulating at x = 0 (x = L), and Id = 0 for a spatially homogeneous state.

In Fig. 3a, we take averages over all continuous states for the IPRs and directed IPRs (\(\bar{I}({\mu }_{\alpha }^{\pm })\) and \({\bar{I}}_{d}({\mu }_{\alpha }^{\pm })\)), and present them as functions of A. Note that for μ ≫ 1, the continuous eigenstates have vanishing amplitude at x = 0, analogous to a system with L, not L + 1 sites. Therefore, to properly compare the averaged IPRs between large and small μ, they are rescaled as \((\bar{I},{\bar{I}}_{d})\to (\bar{I},{\bar{I}}_{d})L/(L+1)\) for μ > eα, and the system’s center is redefined as xc = (L − 1)/2 for the directed IPR. We can see from Fig. 3a that the quasi-PBCs and PBCs are recovered at A = eα for \(\mu ={\mu }_{\alpha }^{\pm }\) respectively, where \(\bar{I}(\mu )=1/(L+1)\) and \({\bar{I}}_{d}(\mu )=0\) as all eigenstates are fully delocalized. The IPR profiles agree well between the dual values of μ in the regime close to PBCs and quasi-PBCs (A ~ eα), but begin to diverge when A gets larger.

a and b Average inverse participation ratios (IPRs) defined as \(\bar{I}(\mu )={\sum }_{n}{I}_{n}/N\) and \({\bar{I}}_{d}(\mu )={\sum }_{n}{I}_{n,d}/N\), with In = \({\sum }_{x}\)∣ψx,n∣4 and Id,n = \({\sum }_{x}\)(xc − x)∣ψx,n∣4/(L/2), ψx,n the wave-function value of the nth eigenstate at x, N and L the total number of states and lattice sites, and xc = L/2 being the center of the system. The impurity strength μ is parametrized by a variable A, i.e. \(\mu ={\mu }_{\alpha }^{\pm }={e}^{\alpha }{A}^{\pm 1}\) and \(\mu ={\mu }_{0}^{\pm }={A}^{\pm 1}\) for (a) and (b), respectively. In (a), \({\mu }_{\alpha }^{+}\) and \({\mu }_{\alpha }^{-}\) form a pair of duality, whereas in (b) with much larger A values, \({\mu }_{0}^{+}\) and \({\mu }_{0}^{-}\) form a pair of duality. The summation of n runs over all continuous eigenstates, and N = L−1 (L + 1) is their total number in the presence (absence) of the pair of isolated states Eiso ≈ ± μ. Colors of the curves indicate IPRs for different choices of μ. Blue and orange curves are almost identical in (a). c Spectra with dual parameters, as indicated by the gray arrows. A phase transition to OBC-like line-spectrum at μ = e±(L+1)α = e±21, with the parameters L = 20 and α = 1. The duality indicated in (a) is further confirmed by the identical spectra (blue circles and red stars) of \(\mu ={\mu }_{\alpha }^{\pm }\) (with α = 1), at A = 0.5 and A = 2 for the left two panels, respectively. Similarly, the two panels on the right depict the duality between \(\mu ={\mu }_{0}^{\pm }\) indicated in (b), for the two points of A = 20.5 and A = 21.

To understand this divergence, we unveil a second duality between μ ~ e(L+1)α and μ ~ e−(L+1)α, the latter corresponds to a transition between the qualitative spectral properties found for PBCs (loops) and OBCs (lines)26,40. In Fig. 3b, we illustrate both IPRs for \(\mu ={\mu }_{0}^{\pm }\) as functions of the variable A, i.e. \({\mu }_{0}^{\pm }={A}^{\pm 1}\). The above PBC–OBC transition is seen as \(\bar{I}({\mu }_{0}^{-})\) and \({\bar{I}}_{d}({\mu }_{0}^{-})\) become constant for \(\mathrm{ln}\,A\,\geqslant \,(L+1)\alpha\), reflecting the OBC skin modes. Interestingly, a similar transition also occurs at large μ = e(L+1)α, characterized by the constant IPRs in Fig. 3b when μ exceeds the critical value, indicating a second duality between \(\mu ={\mu }_{0}^{\pm }\) in the large A limit. These IPRs take different saturation values mainly because of the rescaling in the large μ regime with effectively different number of sites. The critical value for this transition can also be identified from our approximation of Eq. (1), where the decay exponent κL = α at μ = e(L+1)α, recovering the decay exponent (and the imaginary flux) κOBC for NHSE under OBCs. In Fig. 3c, we illustrate the spectra with several pairs of dual parameters, clearly showing the two types of dualities and the transition to a OBC-like spectrum.

Co-existence of different regimes

The decay exponents κL(μ) of SFA states, as induced by the impurity, are insensitive to the exact configuration of non-reciprocal hoppings in the bulk. By contrast, skin modes under OBCs may have k-dependent decay exponents κOBC(k) if the system has hoppings beyond nearest neighbors45. That is1,2,3, the GBZ describing the NHSE under OBCs is given by \(z:={e}^{i[k+i{\kappa }_{{\rm{OBC}}}(k)]}\), and may not be a prefect circle on the complex plane. On the other hand, the decay exponents κL(μ) also suggests an effective GBZ given by \({z}_{{\rm{SFA}}}:={e}^{i[k+i{\kappa }_{L}(\mu )]}\), which is always a prefect circle with its radius determined by μ. Requiring κL(μc) = κOBC(k), one finds a k-dependent critical value of μc(k), where the GBZ of z and the effective one of zSFA coincide at the corresponding k. A remarkable consequence then arises from this competition, namely, the co-existence of the SFA and NHSE for different eigenstates at a fixed μ. Physically, this coexistence reflects that at different wavenumbers k, an eigenstate effectively experiences couplings across different distances.

Consider a system with different forward and backward couplings ranges and an impurity between x = 0 and L:

The decay exponents for the SFA at μ ≪ 1 and the NHSE under OBCs can be obtained as45 (see the “Methods” section)

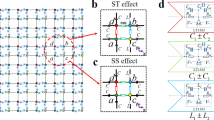

with j = ⌊(k + π/3)/(2π/3)⌋. In Fig. 4a–c we illustrate these two quantities versus k for different μ. Together with the spectra in Fig. 4d–f, we see that an eigenstate always obeys the localization behavior with the smaller decaying exponent. That is, all eigenstates exhibit the SFA when κL < κOBC(k) in Fig. 4a and d, and the NHSE when κL > κOBC(k) in Fig. 4c and f. In the intermediate regime of Fig. 4b and e, the SFA and NHSE co-exist for different k, as the spectrum follows the prediction of SFA when k ∈ [k2m−1, k2m] (m = 1, 2, 3) where κL is smaller, and the prediction of the NHSE otherwise, with k2m and k2m−1 being the six special momentum values marked on Fig. 4b for which κL = κOBC. As also seen from Fig. 4, due to the possibility of coexistence of the SFA and NHSE accumulation, even the qualitative spectral features are extremely sensitive to boundary impurity parameter μ, an observation of general interest when it comes to build a sensing platform based on non-Hermiticity.

a–c Decaying exponents κL and κOBC(k) of the SFA and NHSE, respectively, for the Hamiltonian of Eq. (5) with different boundary impurities μ. d–f Their corresponding spectra under different parameters and different boundary conditions. The blue lines, blue circles, and gray dots in d–f correspond to the spectra of the SFA with eigenenergy given by E = ϵ(k + iκL), numerical results with a boundary impurity, and the NHSE where E = ϵ(k + iκOBC(k)) respectively, with ϵ(k) the eigenenergy under periodic boundary conditions. The system’s parameters are α = 1, L = 80, and μ = e−30, e−45, and e−60 from left to right.

Proposed experimental demonstration

As steady-state phenomena, the SFA can be most easily demonstrated in an electrical circuit setting. In place of the Hamiltonian, we consider the circuit Laplacian J which governs its steady-state response via I = JV, where the components of V and I are, respectively, the electrical potentials and input currents at each node. The eigenspectra and eigenstates of J can be directly resolved by measuring the voltage profile46,47 viz.

where \(\left|{\psi }_{\lambda }^{{\mathrm{{L}}}/{\mathrm{{R}}}}\right\rangle\) are the left/right eigenvectors of J corresponding to eigenvalue ϵλ, and Vα, \(\langle \alpha | {\psi }_{\lambda }^{{\mathrm{{R}}}}\rangle\) are, respectively, the potential and \({\psi }_{\lambda }^{{\mathrm{{R}}}}\) values at the αth node. To isolate a particular \(\lambda ^{\prime}\)th eigenmode, we tune the circuit until \({\epsilon }_{\lambda ^{\prime} }\approx 0\), either by adjusting its variable components or by varying the AC frequency ω46. Vα is then dominated by \({\epsilon }_{\lambda ^{\prime} }^{-1}\langle \alpha | {\psi }_{\lambda ^{\prime} }^{{\mathrm{{R}}}}\rangle \langle {\psi }_{\lambda ^{\prime} }^{{\mathrm{{L}}}}| {\bf{I}}\rangle\). If we further connect an input current I0 to a fixed node \(\beta ^{\prime}\) (the current leaves via the ground), \(\langle {\psi }_{\lambda ^{\prime} }^{{\mathrm{{L}}}}| {\bf{I}}\rangle ={I}_{0}{\langle \beta ^{\prime} | {\psi }_{\lambda ^{\prime} }^{{\mathrm{{L}}}}\rangle }^{* }\) and the eigenstate profile \(\langle \alpha | {\psi }_{\lambda ^{\prime} }^{{\mathrm{{R}}}}\rangle\) across all nodes α becomes approximately proportional to the measured potential profile Vα i.e.

In other words, \({\psi }_{\lambda ^{\prime} }^{{\mathrm{{R}}}}\) can be approximately measured through V when it is topolectrically resonant (\({\epsilon }_{\lambda ^{\prime} }\approx 0\)).

A circuit Laplacian J with a similar form as H of Eq. (1) can be realized with the L + 1-node LC circuit of Fig. 5a. Adjacent nodes acquire asymmetric non-Hermitian couplings through a negative impedance converter with current inversion (INIC)48,49 in series with a capacitor C1, which together contribute an admittance of \(i\omega {C}_{1}\left(\begin{array}{ll}-1&1\\ -1&1\end{array}\right)\) to the Laplacian48 (see the “Methods” section). The extent of asymmetry is regulated by another parallel capacitor C2, such that \({C}_{1}/{C}_{2}=\tanh \alpha\) (see the “Methods” section). To implement an "impurity” coupling between nodes L and 0, we connect an extra variable inductor l in series with the parallel INIC + capacitors configuration, such that the admittance in both directions is uniformly scaled by a factor of \(\mu (\omega )=\mu (\omega )={(1-{\omega }^{2}l({C}_{2}-{C}_{1}))}^{-1}\) (see the “Methods” section). To measure the profile of a desired eigenmode \({\psi }_{\lambda ^{\prime} }^{{\mathrm{{R}}}}\), we first need to shift its eigenvalue \({\epsilon }_{\lambda ^{\prime} }\) maximally close to 0. This can be achieved with additional identical grounding inductors lg at each bulk node, together with more carefully designed grounding circuits j0, jL at the impurity nodes (see the “Methods” section). In all, our circuit Laplacian takes the form

where \({C}_{1}=C\sinh \alpha\), \({C}_{2}=C\cosh \alpha\) and \({\omega }_{0}^{-2}={l}_{gr}C\), which is equal to −iωCH (Eq. (1)) up to a tunable real shift (the \(\left|x\right\rangle \left\langle x\right|\) term). Plotted in Fig. 5b are simulated impedance measurements \({Z}_{0,L}={\sum }_{\lambda }{\epsilon }_{\lambda }^{-1}\left\langle {{\Delta }}| {\psi }_{\lambda }^{{\mathrm{{R}}}}\right\rangle \left\langle {\psi }_{\lambda }^{{\mathrm{{L}}}}| {{\Delta }}\right\rangle\), \(\left|{{\Delta }}\right\rangle =\left|0\right\rangle -\left|L\right\rangle\)46 across the impurity as ω is varied, for different μ(ω) = μ adjusted through the inductors l. The impedance peaks correspond to values of ω where a Laplacian eigenvalue ϵ ≈ 0. For instance, the strongest peaks belonging to \(\mathrm{ln}\,\mu =0,1\) arise from eigenvalues already on the real line (inset), while the weakest peaks from \(\mathrm{ln}\,\mu =2\) are due to eigenvalues far from the real line. The entire spectrum (inset) can be reconstructed via systematic impedance measurements28,47.

a The circuit of Eq. (8), whose asymmetric couplings are implemented through a negative impedance converter with current inversion (INICs) and capacitors. The extra variable inductor l gives rise to a coupling "impurity’’. Suitably designed grounding elements (see the “Methods” section) enable desired eigenstates to be isolated at appropriate driving voltage frequency ω. b Simulated impedance measurements across the impurity at various impurity strength μ, with position ω and height of impedance peaks loosely corresponding to the real and imaginary parts of the spectrum ϵ/(iωC) (inset). Here the capacities of C1 and C2 are parameterized as \({C}_{1}=C\sinh \alpha\), \({C}_{2}=C\cosh \alpha\). Parameters used are L = 9, C1 = 1 and C2 = 3, so that \(C=\sqrt{8}\) and α = 0.364. c Simulated electrical potential measurements vs. the profile of the bulk eigenstate with largest ϵ/(iωC), tuned close to resonance via Eq. (2). Not only is Eq. (7) accurate, the nature of eigenstate accumulation also agrees perfectly with the regimes of Fig. 1d. Parameters are L = 20, C1 = 2.9, C2 = 3, such that 2α ≈ 4.

At these impedance peaks, the potential profile approximately corresponds to the eigenstate profile of the resonant eigenmode, as verified by simulated measurements (Fig. 5c). We clearly observe reversed and non-reversed eigenstates at different μ, perfectly as predicted (Figs. 1d and 2a). Physically, the reversed voltage profile is a steady-state solution that represents a compromise between the competing non-reciprocal feedback mechanisms from the op-amps in the INICs. Scale-free behavior can be similarly detected when new nodes are introduced. More generally, we expect to measure these new forms of impurity-induced eigenstate accumulation in a variety of media whose steady-state description involve non-Hermitian asymmetric couplings49,50,51.

Discussion

The key and surprising finding of this work is the impurity-induced scale-free decay of steady states in a non-Hermitian non-reciprocal lattice. On the one hand the steady states are exponentially localized; on the other hand the decay exponent is inversely proportional to the system’s size, hence the overall decay is free of system’s size. This peculiar scale-free feature may be first observed in an electrical circuit setting. We have also found rich transitions between NHSE, Bloch-like, and SFA eigenstates along or against the direction of non-reciprocity, with stimulating duality relations between cases of weak and strong impurity strengths. Recognizing now that the well-known NHSE is only one of many impurity-induced consequences, a new basket of non-Hermitian phenomena waits to be discovered. The coexistence of SFA and NHSE can be highlighted, because of which even qualitative spectral features of a non-Hermitian system can be extremely sensitive to some system parameters. This finding may lead to new sensing-related applications of non-Hermitian lattices.

This work also hints that even more exotic phenomena can be expected with spatial inhomogeneity beyond the single impurity cases considered here. One straightforward extension is to consider multiple impurities with independent strengths, each can lead to the SFA or NHSE individually. In this scenario different segments separated by these impurities may exhibit different localization behaviors, and a complete framework of such phenomena still awaits further studies.

Methods

SFA in the Hatano–Nelson model with a boundary impurity

Strong impurity

We consider the following Hamiltonian:

Solving eigen-equation HΨn = EnΨn with \({{{\Psi }}}_{n}=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{x}^{L}{\psi }_{x,n}{\hat{c}}_{x}^{\dagger }\left|0\right\rangle\) the nth eigenstate of the system, we obtain the following recursive conditions:

for x = 1, 2, . . . , L − 1, and

Intuitively, when μ is large, two isolated solutions localized around x = 0 and x = L are expected due to the strong couplings between these two sites. Assuming these solutions decay exponentially from the two sites into the bulk, we find that they can be explicitly expressed as

whose eigenenergies are given by

These solutions are valid provided that μ > e±α, so that they indeed decay from x = 0 and x = L into the bulk; and \({({e}^{\pm \alpha }/\mu )}^{L} \sim 0\), so that they have vanishing amplitudes in the middle of the system. In the main text, we have assumed μ ≫ e±α, therefore the above conditions are satisfied and we have \({E}_{{\rm{iso}}}^{\pm }\approx \pm \mu\).

For convenience, we label these two isolated eigenstates with n = 0 and n = L, respectively. The other L − 1 eigenstates of n ∈ [1, L − 1], referred to as continuous eigenstates as they have a continuous spectrum, shall mainly distribute within the rest L − 1 sites of the system with eigenenergies En ≪ μ. Thus one expects a vanishing ψ0,n from Eq. (11). We further consider an ansatz of exponentially decaying eigenstates given by

Substituting the ansatz into Eq. (12), we obtain

yielding

However, Eqs. (10) and (11) give different eigenenergies for the exponentially decaying solutions. A consistent solution can be obtained by further requiring eα ≫ e−α and \({e}^{\alpha }{e}^{-{M}_{n}}\gg {e}^{-\alpha }{e}^{{M}_{n}}\). The first condition corresponds to a strong non-reciprocity of the system, and the second one is equivalent to μ ≪ e(L+1)α, which is generally satisfied for a large enough system. Under these conditions, Eq. (10) gives

with kn: = (2n + 1)π/(L−1), n = 1, 2, . . . , L−1, and ϵ(k) ≈ eαeik the eigenenergies under PBCs and strong non-reciprocity. On the other hand, since now we have μ ≫ eα ~ En ≫ e−α, the second term of Eq. (11) can be neglected, yielding

which is consistent with the vanishing ψ0,n obtained previously.

Weak impurity

Next we consider a weak impurity limit with μ ≪ 1 and a strong non-reciprocity eα ≫ e−α, and correspondingly a different ansatz

with Mn > 0 (because we do not observe any cases with reversed accumulation in the regime with μ < 1). Thus Eq. (12) is simplified to

Substituting the above equation into Eq. (11) with its second term being neglected, one can obtain

This solution also confirms that the second term of Eq. (11) is negligible as compared with the rest two terms. The eigenenergies are thus directly given by Eq. (21).

Quasi-PBC delocalized eigenstates

To gain further insights into the quasi-PBCs at μ = 2α, let us exploit the following effective translational invariant Hamiltonian, \({\bar{H}}_{{\rm{PBC}}}(k)={H}_{{\rm{PBC}}}(k+i{\kappa }_{L})\), with its real-space form being

In above site L + 1 is understood as site 0. According to our spectral results in Eq. (2) in the main text, \({\bar{H}}_{{\rm{PBC}}}\), though having an extra κL-related imaginary flux, yields the approximate eigenvalues of our lattice system for \(\mu ={e}^{(L-1){\kappa }_{L}+2\alpha }\). We next remove the imaginary flux in the bulk by applying a similarity transformation \(\bar{H}^{\prime} ={S}_{L}^{-1}{\bar{H}}_{{\rm{PBC}}}{S}_{L}\) with \({S}_{L}={\rm{Diag}}\{1,{e}^{{\kappa }_{L}},{e}^{2{\kappa }_{L}},...,{e}^{{\kappa }_{L}L}\}\). This gives (without changing the eigenvalues)

So long as L is sufficently large, we still have \({\kappa }_{L}(L+1)\approx \mathrm{ln}\,\mu -2\alpha\), thus the boundary hopping in \(\bar{H}^{\prime}\) shown above becomes

It is seen that at μ = e2α, \(\bar{H}^{\prime}\) recovers the original Hamiltonian under PBCs. This is fully consistent with the observation from Eq. (1) in the main text, namely, the decay exponent κL = 0 for μ = e2α. The above treatment is however more stimulating to digest situations with μ ≠ e2α, where the translational invariance of \(\bar{H}^{\prime}\) is broken at the boundary. For μ > e2α, the hopping from x = L to x = 0 is further enhanced whereas the opposite hopping is further suppressed (as respectively, compared with the translational invariant case). The eigenstates are then expected to populate more at x = 0. Likewise, eigenstates should accumulate more at x = L when μ < e2α, thereby exhibiting the reversed SFA.

Different accumulating behaviors of the model with two non-reciprocity length scales

We consider a system with nearest-neighbor backward couplings and next-nearest-neighbor forward couplings, and a local impurity between sites x = 0 and x = L, described by the Hamiltonian

Solving for eigen-function HNNNΨn = EnΨn with \({{{\Psi }}}_{n}=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{x}^{L}{\psi }_{x,n}{\hat{c}}_{x}^{\dagger }\left|0\right\rangle\), the recursive conditions of ψx,n are given by

for x = 1, 2, . . . , L−1, and

Similar to the model of Eq. (9) at weak impurity limit, we consider the parameter regime with μ ≪ 1 and eα ≫ e−α, and the same SFA solution can be obtained as

On the other hand, to solve the OBC system with μ = 0, we consider an imaginary flux κOBC(k) under PBCs, corresponding to an effective Hamiltonian

with \(z={e}^{i[k+i{\kappa }_{{\rm{OBC}}}(k)]}\). The OBC system is described by a GBZ, where the eigenenergies satisfy \(\bar{E}({k}_{1})=\bar{E}({k}_{2})\) for pairs of quasi-momenta with κOBC(k1) = κOBC(k2). Numerically, we find that this condition is satisfied when k1 + k2 = 0, 2π/3, and 4π/3, for k1, k2 ∈ [ − π/3, π/3], [π/3, π], and [π, 5π/3], respectively. With these relations between k1 and k2, we obtain

with j = ⌊(k + π/3)/(2π/3)⌋.

Derivation of circuit Laplacian

Here we provide a detailed derivation of the Laplacian (Eq. (8) of the main text) of the circuit as illustrated in Fig. 5 of the main text, and also furnish more details about its grounding connections. This circuit design is inspired by previous experimental cicuit realizations of various topological and non-Hermitian states46,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59.

The Laplacian J is defined as the operator that connects the vectors of input current and electrical potential via I = JV. In this work, we design a circuit array that (i) is non-Hermitian and non-reciprocal, with right/left couplings proportional to e±α, (ii) has special impurity couplings (in both directions) that are stronger than the rest by a tunable factor of μ = μ(ω) and (iii) also contains suitable grounding elements that allows the Laplacian eigenvalue spectrum to be shifted uniformly as desired.

For (i), the unbalanced couplings ∝ e±α can be implemented by a parallel configuration of a capacitor C2, and a combination of another capacitor C1 that is connected in series with an INIC (negative INIC). As elaborated in ref. 48, an INIC is an arrangement of operation amplifiers (op-amps) that reverses the sign of the impedance of components “in front of” it. Specifically, for a generic ideal INIC configuration as shown in Fig. 6a, the input currents and potentials at the two ends obey

where ZA, ZB are the impedances of components A and B. The Laplacian matrix above is not just asymmetric and hence non-Hermitian, but is also inversely proportional to the difference between the two impedances, contrary to the usual case without the INIC.

a Two generic elements with impedances ZA, ZB connected in series at either side of a negative impedance converter with current inversion (INIC) (elaborated in ref. 48) give rise to a non-Hermitian Laplacian Eq. (33). b Asymmetric couplings of the simplest form (Eq. (34)) can be realized with a parallel configuration containing one INIC and two capacitors. c An impurity bond consisting of tunable equivalently rescaled asymmetric couplings (Eq. (36)) can be realized with a variable inductor l connected in series with JNN. d, e Explicit example realizations of j0, jL grounding components needed to make the grounding terms of the impurity nodes equivalent to the others’. Changing the AC frequency ω leads to a uniform shift in Laplacian eigenvalues through \({(i\omega {l}_{{\mathrm{{gr}}}})}^{-1}\).

To implement the ∝ e±α couplings, we consider parallel configurations of two capacitors C1, C2, one on its own, and the other in series with an INIC (Fig. 6b). This gives a Laplacian contribution of

if we set \({C}_{1}=C\sinh \alpha\), \({C}_{2}=C\cosh \alpha\), \(C=\sqrt{{C}_{2}^{2}-{C}_{1}^{2}}\) a reference capacitance scale. If we connect each node of a OBC linear circuit array with these parallel configuration units, we end up with the Laplacian

Note that the coefficient of \(\left|x\right\rangle \left\langle x\right|\) merely sums out the total outgoing hopping amplitude.

To implement (ii) the impurity couplings that are equally asymmetric, but larger than the other couplings by a factor of μ, we connect a tunable inductor l with admittance (iωl)−1 in series with the abovementioned parallel configuration (Fig. 6c). Elementary applications of Kirchhoff’s law gives us

which is proportional to JNN at the two nodes coupled by the impurity, up to a factor of \(\mu (\omega )=\frac{1}{1-{\omega }^{2}({C}_{2}-{C}_{1})l}\). In other words, the impurity strength μ(ω) can be adjusted both by changing the AC frequency ω, or by tuning the inductor l itself. Note that the upper-left term of Jbdry. NN reduces to the simple result that the combined impedance of components connected in series is just the sum of their impedances.

The third important feature (iii), which is the implementation of grounding components that allow for a uniform shift in Laplacian eigenvalues, is more tricky. With ground connections given by \({J}_{\text{gr}}=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{x = 0}^{L}{j}_{x}\left|x\right\rangle \left\langle x\right|\), the circuit Laplacian we have is given by (impurity is between the Lth and 0th nodes)

Notably, the on-site terms are not even uniform. For identification with the Hatano–Nelson model with a single coupling impurity (see the main text), we need to add grounding terms such that they are not just uniform but also tunable i.e. giving rise to a tunable multiple of the (L + 1)-by-(L + 1) identity matrix. Since nodes 1 through L−1 already have the same onsite coefficient of \(2i\omega C\cosh \alpha\), we just need to ground them via identical inductors lgr, such that \({j}_{x}={(i\omega {l}_{\text{gr}})}^{-1}\) for x = 1, . . . , L−1. The more tricky part is grounding nodes 0 and L with appropriate sets of components with combined admittance j0, jL such that all onsite terms are equal. We first tidy up Eq. (37) such that the NN couplings, bulk groundings and impurity groundings are grouped together:

For all onsite terms to be equal, we hence require that

Recall from Eq. (36) that iωμ(ω)(C2 ± C1) are the admittances of the Jimp. NN configuration with respect to the ground. The remaining admittances iω(C2 ± C1) can be realized by the configuration of JNN (Eq. (34)). As such, j0 and jL can be realized by the configurations illustrated in Fig. 6d, e.

All in all, our circuit Laplacian takes the form

whose realization is illustrated in Fig. 5 of the main text.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from any of the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Yao, S. & Wang, Z. Edge states and topological invariants of non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 086803 (2018).

Yokomizo, K. & Murakami, S. Non-bloch band theory of non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 066404 (2019).

Lee, C. H. & Thomale, R. Anatomy of skin modes and topology in non-hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. B 99, 201103 (2019).

Lee, C. H. et al. Tidal surface states as fingerprints of non-Hermitian nodal knot metals. Preprint at arXiv:1812.02011 (2018).

Kunst, F. K. & Dwivedi, V. Non-hermitian systems and topology: a transfer-matrix perspective. Phys. Rev. B 99, 245116 (2019).

Edvardsson, E., Kunst, F. K. & Bergholtz, E. J. Non-Hermitian extensions of higher-order topological phases and their biorthogonal bulk-boundary correspondence. Phys. Rev. B 99, 081302 (2019).

Yang, Z., Zhang, K., Fang, C. & Hu, J. Non-Hermitian bulk-boundary correspondence and auxiliary generalized brillouin zone theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 226402 (2020).

Zhang, K., Yang, Z. & Fang, C. Correspondence between winding numbers and skin modes in non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 126402 (2020).

Brandenbourger, M., Locsin, X., Lerner, E. & Coulais, C. Non-reciprocal robotic metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–8 (2019).

Lee, C. H., Li, L. & Gong, J. Hybrid higher-order skin-topological modes in nonreciprocal systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 016805 (2019).

Mu, S., Lee, C. H., Li, L. & Gong, J. Emergent fermi surface in a many-body non-Hermitian fermionic chain. Phys. Rev. B 102, 081115 (2020).

Li, L., Lee, C. H. & Gong, J. Geometric characterization of non-Hermitian topological systems through the singularity ring in pseudospin vector space. Phys. Rev. B 100, 075403 (2019).

Lee, C. H. & Longhi, S. Ultrafast and anharmonic Rabi oscillations between non-bloch bands. Commun. Phys. 3, 147 (2020).

Longhi, S. Non-bloch-band collapse and chiral zener tunneling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 066602 (2020).

Lee, C. H. Many-body topological and skin states without open boundaries. Preprint at arXiv:2006.01182 (2020).

Cao, Y., Li, Y. & Yang, X. Non-Hermitian bulk-boundary correspondence in periodically driven system. Preprint at arXiv:2007.13499 (2020).

Xue, W.-T., Li, M.-R., Hu, Y.-M., Song, F. & Wang, Z. Non-Hermitian band theory of directional amplification. Preprint at arXiv:2004.09529 (2020).

Liu, C.-H., Zhang, K., Yang, Z. & Chen, S. Helical damping and dynamical critical skin effect in open quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 043167 (2020).

Rosa, M. N. & Ruzzene, M. Dynamics and topology of non-Hermitian elastic lattices with non-local feedback control interactions. New J. Phys. 22, 053004 (2020).

Yoshida, T., Mizoguchi, T. & Hatsugai, Y. Mirror skin effect and its electric circuit simulation. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 022062 (2020).

Yi, Y. & Yang, Z. Non-Hermitian skin modes induced by on-site dissipations and chiral tunneling effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 186802 (2020).

Xiao, L. et al. Non-Hermitian bulk-boundary correspondence in quantum dynamics. Nat. Phys. 16, 761–766 (2020).

Li, L., Lee, C. H. & Gong, J. Topological switch for non-hermitian skin effect in cold-atom systems with loss. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 250402 (2020).

Schomerus, H. Nonreciprocal response theory of non-hermitian mechanical metamaterials: response phase transition from the skin effect of zero modes. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 013058 (2020).

Okuma, N., Kawabata, K., Shiozaki, K. & Sato, M. Topological origin of non-hermitian skin effects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 086801 (2020).

Koch, R. & Budich, J. C. Bulk-boundary correspondence in non-hermitian systems: stability analysis for generalized boundary conditions. Eur. Phys. J. D 74, 1–10 (2020).

Teo, W. X. T., Li, L., Zhang, X. & Gong, J. Topological characterization of non-Hermitian multiband systems using Majorana’s stellar representation. Phys. Rev. B 101, 205309 (2020).

Li, L., Lee, C. H., Mu, S. & Gong, J. Critical non-Hermitian skin effect. Nat. Commun. 11, 5491 (2020).

Arouca, R., Lee, C. H. & Morais Smith, C. Unconventional scaling at non-hermitian critical points. Phys. Rev. B 102, 245145 (2020).

Bosch, M., Malzard, S., Hentschel, M. & Schomerus, H. Non-Hermitian defect states from lifetime differences. Phys. Rev. A 100, 063801 (2019).

Liu, C.-H. & Chen, S. Topological classification of defects in non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. B 100, 144106 (2019).

Fu, L. B., Yi, X. X., Zhao, X. L. & Chen, L. B. Topological phase transition of non Hermitian crosslinked chain. Ann. Phys. 532, 1900402 (2020).

Liu, Y. & Chen, S. Diagnosis of bulk phase diagram of nonreciprocal topological lattices by impurity modes. Phys. Rev. B 102, 075404 (2020).

Luo, X.-W. & Zhang, C. Non-Hermitian disorder-induced topological insulators. arXiv:1912.10652 (2019).

Longhi, S. Topological phase transition in non-hermitian quasicrystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 237601 (2019).

Jiang, H., Lang, L.-J., Yang, C., Zhu, S.-L. & Chen, S. Interplay of non-Hermitian skin effects and anderson localization in nonreciprocal quasiperiodic lattices. Phys. Rev. B 100, 054301 (2019).

Zeng, Q.-B., Yang, Y.-B. & Xu, Y. Topological phases in non-Hermitian Aubry–André–Harper models. Phys. Rev. B 101, 020201 (2020).

Claes, J. & Hughes, T. L. Skin effect and winding number in disordered non-Hermitian systems. Preprint at arXiv:2007.03738 (2020).

Xiong, Y. Why does bulk boundary correspondence fail in some non-Hermitian topological models. J. Phys. Commun. 2, 035043 (2018).

Kunst, F. K., Edvardsson, E., Budich, J. C. & Bergholtz, E. J. Biorthogonal bulk-boundary correspondence in non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 026808 (2018).

Budich, J. C. & Bergholtz, E. J. Non-Hermitian topological sensors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 180403 (2020).

McDonald, A. & Clerk, A. A. Exponentially-enhanced quantum sensing with non-Hermitian lattice dynamics. Nat. Commun. 11, 5382 (2020).

Hatano, N. & Nelson, D. R. Localization transitions in non-Hermitian quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 570–573 (1996).

Fleischhauer, M., Imamoglu, A. & Marangos, J. P. Electromagnetically induced transparency: optics in coherent media. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 633–673 (2005).

Lee, C. H., Li, L., Thomale, R. & Gong, J. Unraveling non-Hermitian pumping: emergent spectral singularities and anomalous responses. Phys. Rev. B 102, 085151 (2020).

Lee, C. H. et al. Topolectrical circuits. Commun. Phys. 1, 1–9 (2018).

Helbig, T. et al. Band structure engineering and reconstruction in electric circuit networks. Phys. Rev. B 99, 161114 (2019).

Hofmann, T., Helbig, T., Lee, C. H., Greiter, M. & Thomale, R. Chiral voltage propagation and calibration in a topolectrical chern circuit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 247702 (2019).

Helbig, T. et al. Generalized bulk–boundary correspondence in non-Hermitian topolectrical circuits. Nat. Phys. 16, 747–750 (2020).

Hofmann, T. et al. Reciprocal skin effect and its realization in a topolectrical circuit. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 023265 (2020).

Weidemann, S. et al. Topological funneling of light. Science 368, 311–314 (2020).

Ningyuan, J., Owens, C., Sommer, A., Schuster, D. & Simon, J. Time-and site-resolved dynamics in a topological circuit. Phys. Rev. X 5, 021031 (2015).

Imhof, S. et al. Topolectrical-circuit realization of topological corner modes. Nat. Phys. 14, 925 (2018).

Kotwal, T. et al. Active topolectrical circuits. Preprint at arXiv:1903.10130 (2019).

Lu, Y. et al. Probing the berry curvature and fermi arcs of a weyl circuit. Phys. Rev. B 99, 020302 (2019).

Olekhno, N. A. et al. Topological edge states of interacting photon pairs emulated in a topolectrical circuit. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–8 (2020).

Lee, C. H. et al. Imaging nodal knots in momentum space through topolectrical circuits. Nat. Commun. 11, 4385 (2020).

Bao, J. et al. Topoelectrical circuit octupole insulator with topologically protected corner states. Phys. Rev. B 100, 201406 (2019).

Zhang, W. et al. Topolectrical-circuit realization of a four-dimensional hexadecapole insulator. Phys. Rev. B 102, 100102 (2020).

Acknowledgements

L.L. started this research at NUS and continued his work after moving to SYSU (Zhuhai). J.G. acknowledges support from the Singapore NRF Grant No. NRF-NRFI2017-04 (WBS No. R-144-000-378-281). C.H.L. acknowledges support from the Singapore MOE Tier I grant (WBS No. R-144-000-435-133).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.L. initiated this project, with input from C.H.L. and J.G. All authors discussed the theoretical and computational results. C.H.L. worked out the experimental proposal using circuits. All authors contributed significantly to the writing. J.G. finalized this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, L., Lee, C.H. & Gong, J. Impurity induced scale-free localization. Commun Phys 4, 42 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-021-00547-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-021-00547-x

This article is cited by

-

Many-body critical non-Hermitian skin effect

Communications Physics (2025)

-

Non-Hermitian delocalization induced by residue imaginary velocity

Communications Physics (2025)

-

Tailoring bound state geometry in high-dimensional non-hermitian systems

Communications Physics (2025)

-

Dynamical suppression of many-body non-Hermitian skin effect in anyonic systems

Communications Physics (2025)

-

Non-Hermitian strong bosonic clustering through interaction-induced caging

Communications Physics (2025)