Abstract

Chiral magnets are known to possess interesting electromagnetic properties that result from the coupling of electrons with nontrivial magnetic phases, such as particle-like magnetic spin textures termed skyrmions. So far, it is unclear how the local and global chirality of magnetic spin textures contributes to the electromagnetic transport responses that have so far been observed. In this work, we focus on unraveling the contributions in the field-dependent longitudinal resistivity response that arises from magnetic spin textures in a centrosymmetric Fe/Gd multilayer that exhibits an array of magnetic phases ranging from stripe, mixed stripe-skyrmion, skyrmion lattice, and disordered skyrmion. Using a combination of transport measurements and micromagnetic simulations, we demonstrate a domain wall chirality reconfiguration occurs as the domain morphology transitions from disordered stripe to skyrmion lattice phase under applied fields that is responsible for the interesting transport responses noted in the field-dependent longitudinal resistivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Skyrmions, particle-like chiral magnetic spin textures, exhibit unique electric and magnetic properties given they carry quantized topological charge1,2. Numerous studies have shown that when conduction electrons interact with these nontrivial spin textures, the electrons couple to the magnetic texture of the skyrmion accumulating a Berry phase that gives rise to an additional Hall contribution, termed topological Hall effect3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Furthermore, magnetoresistance (MR) measurements reveal that a close-packed skyrmion lattice results in a unique signature in the MR-response10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. In general, these electromagnetic properties have primarily been attributed to skyrmions which form in non-centrosymmetric magnets where the presence of a sizeable Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction (DMI) favors a distinct canting between neighboring magnetic spins. Such canting ultimately embeds a single and global chirality among the formed magnetic spin textures. Since these novel electric and magnetic responses tend to result from electrons coupling with skyrmions, we seek of understand how the local and global chirality as well as their spatial arrangement contribute to the observed signatures. The single helicity of DMI skyrmions makes it difficult to discern chirality contributions. On the other hand, dipole-stabilized skyrmions present a testbed to investigate these effects.

Here, we present a transport study of an amorphous Fe/Gd multilayer, of the form [Fe (0.36 nm) /Gd (0.4 nm)]x80, that favors a stripe phase that undergoes a transition to disordered skyrmion phase under applied perpendicular fields at/near room temperature, and a stripe phase that undergoes a field-driven transition into a mixed stripe-skyrmion, close-packed skyrmion lattice, and disordered skyrmion phase at temperatures spanning from T = 180 K to T = 100 K18,19. These skyrmions possess a hybrid structure with a Bloch-line at the center of the film and opposite chirality Néel caps that extend from the center of the film toward the surface18,19,20,21. Given the lack of DMI, the skyrmion phase consists of an equal population of skyrmions with two opposite helicities: if the Bloch-line wraps continuously (S = +1) in a clockwise fashion then it has helicity γ = −π/2; similarly, a skyrmion with Bloch-line that wraps counter-clockwise is said to have helicity = +π/218,19,20,21. Previously, we demonstrated that these chiral spin textures are stabilized under a delicate balance of competing dipolar energy and domain wall energy18,19,20, like achiral stripe and bubble domains (S = 0)22,23,24,25,26,27,28, reason for which we term them dipole-stabilized skyrmions. Our experimental findings in centrosymmetric Fe/Gd multilayers show the magnetic phase transition from stripes to a close-packed skyrmion lattice results in a unique and field-dependent polar longitudinal resistivity anomaly, which differs from observations in non-centrosymmetric magnets where the helicity is preserved under applied magnetic fields10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. By studying field history effects, we observe that the polar longitudinal resistivity anomaly only emerges under specific field reversal conditions. Using numerical simulations, we validate our experimental transport observations and show that the longitudinal resistivity anomaly is correlated to a field-driven Bloch-line reconfiguration, which makes possible the formation of skyrmions under positive and negative magnetic fields in centrosymmetric Fe/Gd multilayers. Overall, our results demonstrate the mechanism by which dipole-stabilized skyrmions form under applied fields in centrosymmetric magnets, as well as show how dipole-stabilized magnetic stripes and skyrmions provide a platform to investigate the interplay between local and global chirality effects.

Results

Temperature- and field-dependent transport responses of the Fe/Gd patterned wire

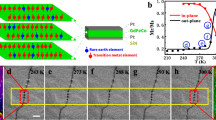

Figure 1a shows the field-dependent polar Hall resistivity (\({\rho }_{{xy}}^{{{\odot}}}\)) obtained for the Fe/Gd patterned wire at T = 300 K. Inspecting the \({\rho }_{{xy}}^{{{\odot}}}\) loop, we can clearly observe signatures the Fe/Gd patterned wire exhibits a stripe phase at zero-field: net zero \({\rho }_{{xy}}^{{{\odot}}}\) is analogous to net zero magnetic moment which indicates an equal population of opposite perpendicular magnetic domains exists at remanence. The monotonic and nonlinear increase in \({\rho }_{{xy}}^{{{\odot}}}\) with applied perpendicular fields, from zero up to the saturated \({\rho }_{{xy}}^{{{\odot}}}\), exhibits a characteristic response commonly seen in magnetic materials hosting stripe phases (i.e., identifying the presence of skyrmion lattice or disordered skyrmion phases is not directly possible from field-dependent magnetometry nor \({\rho }_{{xy}}^{{{\odot}}}\) loops). Figure 1b shows the temperature dependence of the polar longitudinal resistivity (\({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\)) for the Fe/Gd patterned wire under a zero-field-cooling protocol. The measurement shown in Fig. 1b were collected after applying a perpendicular field up to positive saturation and then reducing the field to zero-field. At T = 300 K, the average polar longitudinal resistivity is relatively high (\({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) ~260 μΩ-cm) in comparison to ferromagnetic alloys29 which suggests the amorphous Fe and Gd layers are disordered and there is intermixing between the layers, as we have previously shown in ref. 18. As the temperature is reduced, from T = 300 K to T = 10 K, we observe \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) increases for the Fe/Gd patterned wire which suggests the specimen is semi-metallic; the latter observation is unexpected because most metals exhibit a drop in \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) as the temperature is reduced29.

a Field-dependent polar Hall resistivity (\({\rho }_{{xy}}^{\odot}\)) obtained at room temperature for the 10 μm-wide Fe/Gd patterned wire. The \({\rho }_{{xy}}^{\odot}\) is color-coded to show field-dependent responses: (red-colored) positive-to-negative saturation, while (blue-colored) negative-to-positive saturation. The magnetic field was swept from Hz = ±10 kOe, but for ease of viewing a smaller field range is shown. The inset in a shows the magnetic field and current configurations used to measure the response of the Fe/Gd patterned wire. b The temperature-dependent polar longitudinal resistivity (\({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\odot}\)) of the Fe/Gd patterned wire under a zero-field-cooling (ZFC) protocol; prior to field-cooling, the Fe/Gd patterned wire was saturated with a perpendicular field and then the field was reduced to Hz = 0.

Figure 2 shows the field-dependent parallel (\({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}\)), transverse (\({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }\)), and polar (\({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\)) longitudinal resistivity at discrete temperatures, ranging from T = 300 K to T = 80 K in 20 K steps, for the Fe/Gd patterned wire. In general, we know the longitudinal resistivity response depends on the scatter angle between the current and the magnetization. Lower scattering of electrons is expected from magnetic moments aligned perpendicular and orthogonal to the current flow, whereas moments parallel and anti-parallel to the current flow result in stronger scattering. Because the current is fixed along the length of the wire, different field orientations allow us to probe the behavior of different magnetic spin arrangements more favorably. Considering we know the Fe/Gd film possesses perpendicular magnetic spin textures with hybrid Néel-Bloch-Néel domain walls18,19, we can deduce that: (i) \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) is more sensitive to scattering from magnetic spins in the Bloch-line and Néel caps, while (ii) \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}\) and \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }\) are more sensitive to changes in the perpendicular component of magnetic spins.

a–l Field-dependent parallel (\({{{{{{\rm{\rho }}}}}}}_{{{{{{\rm{xx}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{||}}}}}}}\)), transverse (\({{{{{{\rm{\rho }}}}}}}_{{{{{{\rm{xx}}}}}}}^{\perp }\)), and polar (\({{{{{{\rm{\rho }}}}}}}_{{{{{{\rm{xx}}}}}}}^{{{{{{\rm{\odot}}}}}}}\)) resistivity of the 10 μm-wide Fe/Gd patterned wire from T = 300 K to T = 80 K in 20 K intervals. At each temperature, the magnetic field is swept from H = ±10 kOe, but for ease of viewing a smaller field range is shown. The ρxx is color-coded to show field-dependent responses: (red-colored) positive-to-negative saturation, while (blue-colored) negative-to-positive saturation. The insets, at each temperature, show an enlarged view of features observed in \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\odot}\) as fields are swept from negative to positive saturation.

By surveying the temperature dependence of the zero-field parallel (\({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}\)), transverse (\({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }\)), and polar (\({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\)) longitudinal resistivity for the Fe/Gd patterned wire, shown in Fig. 2, we can gain insights about the domain morphology and its three-dimensional configuration. At room temperature (T = 300 K), both \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}\) and \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }\) exhibit the same electron scattering from the ground state given \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}\left(H=0\right)={\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }\left(H=0\right)\), which is lower than the zero-field polar longitudinal resistivity, \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}(H=0) \, < \, {\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}(H=0)\). Since we know the Fe/Gd multilayer exhibits perpendicular stripe domains with Néel caps and a Bloch-line18,19, we can infer the stripe domains are disordered because the scattering at zero-field is the same along \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}\) and \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }\) (i.e., aligned stripes would result in different electron scattering along parallel or transverse in-plane field geometries). Meanwhile, a higher zero-field \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) suggests the Néel caps occupy a sizable portion of the three-dimensional magnetization volume fraction. As the temperature is reduced, the electron scattering from the ground state along \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}\) and \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }\) both increase at different rates relative to each other, such that \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}(H=0) \, > \, {\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }(H=0)\) below T = 300 K, which indicates perpendicular stripes tend to order transverse the length of the Fe/Gd patterned wire. This rearrangement is possible when the magnetization of the Fe/Gd patterned wire is fully saturated and an applied in-plane field is reduced towards remanence19. Since \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}(H=0) \, > \, {\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }(H=0)\), we can further infer the Néel caps occupy a larger volume fraction of the hybrid domain wall relative to the Bloch-line, and that Néel caps/Bloch-line aligns parallel/transverse to the in-plane field19. Supplementary Note 1 details the anticipated longitudinal resistivity response and orientation of hybrid domain walls with different volume fraction.

Increasing the magnetic field, along either of the three transport configurations [Fig. 2], results in longitudinal resistivity curves that are dependent on the domain morphology. We first focus on interpreting the temperature- and field-dependent \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}\) and \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }\) response. Starting from zero-field, \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}\) and \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }\) curves linearly change with increasing field. The observation of a symmetric \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}\) and \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }\) responses, around zero-field, suggests that the field-dependent domain morphology evolves similarly along both positive and negative field directions. Moreover, the linear response indicates the domains smoothly and continuously tilt in the direction of the applied field. From T = 300 K to T = 100 K, \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}\) and \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }\) exhibit a linear response that narrows around zero-field with decreasing temperature. Above the saturation field (\({H}_{{sat}}\)), \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}\) and \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }\) become constant because the magnetization is uniformly aligned in the direction of the applied field; hence, the scattering of conduction electrons does not change above magnetic saturation. The fact that we observe a reduction in the saturation field along \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}\) and \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }\) implies tilting of the perpendicular magnetic spins in the direction of the applied in-plane field becomes easier as the temperature is lowered; this trend is possible because the Fe/Gd films exhibit a Q-factor, defined as the ratio between uniaxial anisotropy (KU) and shape anisotropy (\(2\pi {M}_{S}^{2}\)), of less than 1 and an effective anisotropy (Keff) that becomes more negative with decreasing temperature18,19. Below T = 100 K, \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}\) exhibits a very weak response between nonuniform and uniform (saturated) magnetic phases, while \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }\) swiftly changes under low in-plane fields.

Next, we focus on the evolution of the field-dependent polar longitudinal resistivity (\({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\)) as a function of temperature, which shows the evidence that the domain morphology undergoes microstructure reconfiguration at/near temperatures at which a close-packed skyrmion lattice phase emerges [Fig. 2]. At room temperature (T = 300 K), \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) exhibits a parabolic field dependence where \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) smoothly decays around zero-field toward magnetic saturation30,31,32,33. The smooth decay of \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) indicates the stripe domains undergo a continuous evolution under applied magnetic fields, a common feature of this magnetic phase. The parabolic trend of \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) is mostly consistent from T = 300 K to T = 260 K, were changes in the Hsat are mostly noted [Fig. 2a–c]. When the temperature is reduced, from T = 240 K to T = 220 K, \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) begins to exhibit a non-symmetric field reversal around zero-field [Fig. 2d, e]. We observe that when the field is swept from negative to positive magnetic saturation, \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) does not smoothly decay in a parabolic fashion, over a narrow field range, above zero-field [Fig. 2e, d, insert]. Similar observations are also noted when the field is reversed from positive to negative magnetic saturation. By further reducing the temperature, from T = 200 K to T = 100 K, the prior kink in the field-dependent \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) becomes a well-defined anomaly [Fig. 2f–k], where \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) tends to locally increase over a narrow field region before it decays at higher magnetic fields in a parabolic trend. The local increase in \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) indicates higher electron scattering takes place, where one would typically expect reduced scattering, which could be explained by a local rearrangement of the three-dimensional magnetic spin textures. Furthermore, we observe that the field range in which the \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) anomaly emerges tends to shift towards zero-field as the temperature is reduced. Below T = 100 K, the amplitude of the \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) anomaly decays, which suggests that the energetics favoring the domain reconfigurations are no longer favorable [Fig. 2l].

Since the anomaly in the \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) is not symmetric with applied fields, we posit microstructural changes in the domain morphology are field history dependent. We performed \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) measurements on the Fe/Gd patterned wire under different field history protocols at two fixed temperatures, one which primarily favors stripe domains (T = 300 K) and the other a close-packed skyrmion lattice (T = 160 K) under applied fields, to gain insights on the origin of the \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) anomaly. The magnetic field history protocols are as follow: (i) First, the perpendicular field is set to positive magnetic saturation, and it is then reduced to negative magnetic saturation; afterwards, the field is swept from negative saturation to positive saturation. This is the field history which has been detailed for measurements shown in Fig. 2. (ii) The second field history protocol proceeds (i) with the perpendicular field being reduced from positive saturation to zero-field, then increasing the field once again to positive saturation, and finally reducing it to zero-field. Figure 3a, b shows the field-dependent \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) at T = 300 K and T = 160 K, respectively, under both field history protocols. At room temperature, we observe that \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) exhibits a parabolic-like field response and there are no indications of any notable anomalies that are dependent on either field history protocol utilized [Fig. 3a]; meanwhile, at low temperatures, field-dependent effects in \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) can clearly be discerned. As before [Fig. 2h], the anomaly in \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) appears under field protocol (i) [Fig. 3b]. For field history (ii), when the field is swept from positive saturation to zero-field, the field-dependent \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) exhibits a parabolic-like trend that mimics the prior field response at high magnetic fields but differs at fields where the \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) anomaly was detected and also exhibits a lower \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) amplitude at magnetic fields preceding the anomaly. These differences suggest that the underlying magnetic spin textures and their ordering differ. Subsequentially increasing the field from zero-field to positive saturation, we observe \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) smoothly decays with a parabolic trend and there is no emergence of the \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) anomaly. Lastly, sweeping the field from positive saturation to zero-field results in a field-dependent \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) response which mimics the prior sweep, thus the field-dependent evolution between magnetic phases is continuous. The transport responses under both field history protocols show that a discontinuous microstructure reconfiguration occurs when transitioning between magnetic close-packed skyrmion lattice phases is stabilized under opposite polarity fields.

a, b Field-dependent polar longitudinal resistivity (\({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\odot}\)) of the 10μm-wide Fe/Gd patterned wire at a T = 300 K and b T = 160 K under two consecutive field history protocols. The inserts in a, b show the Hz field sweep protocols for the four field-dependent \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\odot}\) responses (blue, red, green, black-colored datasets) that were obtained in sequential order at each temperature: the first sweeps are detailed in a, while the subsequent field sweeps are shown in b.

Micromagnetic simulations

To aid unraveling the source of the anomaly in the field-dependent \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\), we performed micromagnetic simulations by solving the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert (LLG) equation using the FastMag micromagnetic simulator34. Using magnetic properties previously identified for these Fe/Gd films18,19, we modeled the equilibrium states which form in a slab with volume of 10 μm × 10 μm × 80 nm which we discretize with 10 nm tetrahedra. To model a slab which supports a close-packed skyrmion lattice we used: saturation magnetization, MS = 400 emu/cm3, uniaxial anisotropy, KU = 4 × 105 erg/cm3 and exchange length, Aex = 5 × 10−7 erg/cm. The equilibrium states on the slab were recorded as the magnetic field was swept from Hz = −5000 Oe to Hz = +5000 Oe in Hz = 50 Oe field steps with 10 ns rise and 20 ns relaxation time, in the high damping regime (α = 1). Since the anisotropic magnetoresistance (AMR) ratio is relatively low for these films (~0.3%), we assume that scattering is uniform across the slab when computing the resistivity at each field step. The resistivity was calculated via:

where ϕ is the angle between the magnetization and current direction. For our simulations, we set \(\Delta \rho =200\mu \varOmega -{cm}\) based on results in Fig. 2 and assume that the current direction is along the two sides of the slab. The overall resistivity resulting from each equilibrium state is calculated as a network of resistors: elements lying in the direction of the current are added in series and elements transverse to the current direction are added in parallel. Figure 4a shows that the calculated field-dependent resistivity exhibits a parabolic-like dispersion with two major anomalies appearing when the field is swept from negative to positive saturation. We overlay the corresponding magnetic phases (disordered stripes [Fig. 4b, c], stripe-skyrmion transition [Fig. 4d, e], skyrmion lattice [Fig. 4f, g], disordered skyrmions [Fig. 4h, i], and uniform magnetization [Fig. 4j, k]) via color-shaded blocks on Fig. 4a to facilitate correlating signatures in the calculated resistivity to different magnetic phases. Supplementary Note 2 shows the field-dependent evolution of the equilibrium states from negative to positive saturation. The first anomaly is abrupt and occurs in a narrow negative field range when transitioning from disordered skyrmions into a close-packed skyrmion lattice. The second anomaly is broad and occurs over a large positive field range within the stripe-skyrmion transition phase. Inspecting the magnetic phases that form under opposite polarity magnetic fields [Fig. 4b–k], distinctions in size and shape of perpendicular domains and their domain walls can be noted (e.g., magnetic spin textures in the stripe, stripe-skyrmion, and skyrmion lattice phase are narrower under negative fields compared to those stabilized under the same positive fields), suggesting that the distribution of the in-plane versus perpendicular magnetic moments differs.

a Field-dependent calculated anisotropic magnetoresistance (AMR) obtained from processing equilibrium states stabilized on a 10 μm × 10 μm × 80 nm slab with 10 nm tetrahedra, and magnetic properties: saturation magnetization, MS = 400 emu/cm3, uniaxial anisotropy, KU = 4 × 105 erg/cm3, and exchange length, Aex = 5 × 10−7 erg/cm. Overlaid on (a) are the respective field-dependent magnetic phases (disordered stripes, stripe-skyrmion transition, skyrmion lattice, disordered skyrmion, uniform magnetization). b–k Equilibrium states, at different perpendicular fields, illustrate the top-side view of the magnetization along the z-axis (mz) at the top surface of the slab (z = 40 nm). The perpendicular magnetization (mz) is represented by regions in red (+mz) and blue (−mz), while the in-plane magnetization (mx, mz) is represented by white regions. Each image depicts a 2 × 2 μm field of view near the center of the 10 × 10 μm total area. The colorbar details the (mz) magnetization polarity detailed in the equilibrium states.

By examining the average magnetization (\( < {m}_{x,y,z} > \)) and average modulus magnetization (\( < |{m}_{x,y,{z}}| > \)), we can obtain insights how individual magnetization components and volume fraction profiles change with applied magnetic fields. Figure 5a–c shows the field-dependent average modulus magnetization (\( < |{m}_{x}| > \), \( < |{m}_{y}| > \), \( < |{m}_{z}| > \)) obtained from processing field-dependent equilibrium states. As expected, the domain wall occupies the highest volume fraction at zero-field [Fig. 5a, b], while at positive/negative saturation all the magnetization is oriented along the negative/positive z-axis [Fig. 5c]. Sweeping the field from one polarity to another, each \( < |{m}_{x,y,{z}}| > \) profile exhibits a parabolic distribution which generally mimics the calculated field-dependent \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\) [Fig. 4a]. Both \( < |{m}_{x}| > \) and \( < |{m}_{y}| > \) exhibit similar distribution with applied fields [Fig. 5a, b], which suggests the volume fraction of mx and my tends to be uniform along the x- and y-axis throughout the domain morphology. In terms of the anomaly features noted in the calculated field-dependent resistivity [Fig. 4a]: the first anomaly, occurring under negative fields, exhibits a sharper/stronger response in \( < |{m}_{x}| > \) and \( < |{m}_{y}| > \) suggesting a more pronounced reconfiguration of the in-plane magnetization (i.e., domain wall) occurs compared to the perpendicular magnetization of the spin textures [Fig. 5a–c]. The second anomaly, occurring under positive fields, tends to show \( < |{m}_{x,y,{z}}| > \) similarly changing when increasing the field from zero-field towards positive saturation. Figure 5d–f shows the field-dependent average magnetization (\( < {m}_{x} > \), \( < {m}_{y} > \), \( < {m}_{z} > \)) obtained from processing field-dependent equilibrium states. As the magnetic field is swept from negative to positive saturation, \( < {m}_{x} > \) and \( < {m}_{y} > \) profiles change polarity with increasing field several times [Fig. 5d, e] at/near field ranges where the anomalies appear [Figs. 4a, 5a, b]; while \( < {m}_{z} > \) tends to monotonically increase with applied fields [Fig. 5f]. Changes in the magnetization polarity suggest the orientation and/or chirality of magnetic spin textures reconfigure with increasing fields.

a–c The field-dependent average modulus of (mx, my, mz) magnetization. d–f The field-dependent average of (mx, my, mz) magnetization. Overlaid on a–f are reference-colors detailing red (positive) and blue (negative) magnetization. g–y Field-dependent evolution of equilibrium states as perpendicular field is swept from negative to positive saturation. Each image shows the top-side view of the magnetization along the x-axis (mx) at the center of the slab (z = 0 nm), or z-axis (mz) at the top surface of the slab (z = 40 nm). All the images capture the evolution of domain states in the same 2 × 2 μm region near the center of the 10 × 10 μm total area. The colorbar details for respective polarity of the (mx, mz) magnetization detailed in the equilibrium states. A reference for the eye is placed in panels a–c at Hz = 0 Oe to aid distinguishing \( < \left|{m}_{x,y,{z}}\right| > \) features between negative and positive fields.

To identify the microstructural changes in the domain morphology that cause \( < {m}_{x} > \) and \( < {m}_{y} > \) to change polarity, we surveyed the field-dependent evolution of the in-plane magnetization along the mid-height of the slab, where Bloch-lines are present. Figure 5g–y shows field-dependent equilibrium states as the field is swept from negative to positive saturation. The images primarily depict the magnetization along the x-axis (mx) at the mid-height of the slab (z = 0 nm), or the magnetization along the z-axis (mz) at the top surface of the slab (z = +40 nm) for select fields. Near the negative critical field (Hz = −2600 Oe), a whole range of cylindrical-like spin textures with S = −1, 0, and +1 chirality (i.e., antiskyrmions35, bubbles, and skyrmions) are formed when the field is reduced below negative saturation [Fig. 5g]. Via field-driven elliptical instabilities26, the cylindrical-like spin textures transform into dumbell-like spin textures retaining their original chirality [Fig. 5h, i]. Within/outside the field-of-view, spin textures with S = 0 and S = −1 tend to collapse or merge with neighboring magnetic spin textures, as the field is increased, and there is a predominance of S = +1 chiral spin textures with coexisting left and right helicities [Fig. 5j, l]. A chiral stripe is represfented by opposite helicity (colored) Bloch-lines along the stripe domain wall (perimeter). As the field approaches zero-field, stripe domains primarily populate the domain morphology with some skyrmions still present [Fig. 5m–o]. Further increasing the field, a local reconfiguration and merger of chiral stripe and skyrmions occurs which results in a domain morphology primarily consisting of achiral stripe domains with many Bloch-points [Fig. 5o–q]. Achiral stripe exhibit the same helicity (color) Bloch-lines on opposite stripe domain walls, while a Bloch point is represented by a white-colored feature on a domain wall where the helicity of the Bloch-line changes from left-to-right or vice versa along the length of the domain wall. The reconfiguration/merger of chiral-to-achiral spin textures results in a local change of chirality for the domain morphology, which takes places near/at fields at which the second anomaly is observed [Fig. 5d, e]. Also noted, under applied fields, is the local rerrangement of Bloch-lines within each stripe [Fig. 5r–t], which is possible due to the displacement of Bloch-points in the stripe domain wall. Increasing the field, achiral stripe domains pinch into cylindrical-like spin textures with S = −1, 0, and +1 chirality, which corresopond to antiskyrmions35, bubbles, and skyrmions, respectively [Fig. 5u, v]. Inspecting the stripe-to-skyrmion and skyrmions lattice phases, we find skyrmions predominantly occupy the domain morphology [Fig. 5u–x]. As the field approaches positive saturation, antiskyrmions35 and bubbles tend to collapse first, while higher fields are required to collapse skyrmions [Fig. 5y]. Recently, we experimentally demonstrated the topological robustness of skyrmions versus bubbles in a similar Fe/Gd multilayer that can be tailored to favor either chiral or achiral phases under different field history protocols36, which matches trends observed in our simulations. Overall, numerical simulations suggest that the field-dependent domain morphology undergoes a three-dimensional local magnetization reconfiguration, which enables the formation of dipole skyrmions under opposite polarity applied fields.

Discussion

To further elucidate competing local and global chirality effects observed in dipole-stabilized magnetic phases, we explore the anticipated perpendicular field transitions of global chiral and achiral magnetic phases. Figure 6a–e schematically details the Bloch-line evolution to support single-helicity skyrmions under opposite applied fields. If we assume the skyrmion lattice phase favors 100% right-handed (R) helicity skyrmions under negative fields [Fig. 6a], then reducing the field towards zero-field results in the elongation of skyrmions into stripe textures that possesses the same 100% right-handed (R) helicity [Fig. 6b]. Under negative fields, both positive and negative magnetization stripe textures possess 100% right-handed (R) Bloch helicity [Fig. 6a, b]. As the field approaches zero, we can expect that the widths of the opposite polarity stripe textures become equivalent [Fig. 6c]. Then, under positive applied fields, the positive/negative polarity perpendicular stripe textures grow/shrink with increasing fields [Fig. 6d] until the shrinking stripes pinch into a collection of 100% right-handed (R) helicity skyrmions [Fig. 6e] (i.e., a perpendicular stripe domain can also coalesce into a skyrmion). The detailed field evolution of 100% right-handed (R) Bloch helicity skyrmion lattice phase, from negative to positive applied fields, demonstrates the Bloch-line helicity is globally and locally conserved. Shifting our focus to achiral global phases, where we anticipate local chirality under opposite applied fields, we can similarly explore the field evolution of chiral spin textures with 50% left-handed (L) and 50% right-handed (R) Bloch helicity. Figure 6f–j illustrates a potential global achiral ground state and an anticipated Bloch-line evolution under applied fields. As before, similar helicity skyrmions elongate into stripe textures that preserve the helicity distribution [Fig. 6f, g]. Under negative and zero fields, the positive magnetization stripes possess 50% left-handed (L) and 50% right-handed (R) Bloch helicity, while negative magnetization stripes exhbit 50% left-handed (L) and 50% achiral (A) Bloch helicity [Fig. 6g, h]. To conserve the local chirality under high positive fields, it is clear that at least one Bloch-line rotation [Fig. 6i] is required to achieve a skyrmion lattice phase consisting of 50% left-handed (L) and 50% right-handed (R) Bloch helicity [Fig. 6j]; alternatively, four Bloch-line rotations would be required to conserve the local chirality at positive fields (see Supplementary Note 3). Given the nature of dipole-stabilized magnetic spin textures with local chirality, there are other potential global achiral ground states, which can also exhibit 50% left-handed (L) and 50% right-handed (R) Bloch helicity, each possessing distinct Bloch-line rotations to conserve local chirality under applied fields. Moreover, multiple global achiral ground states can coexist and locally neighbor one another, which increases the complexity of magnetization dynamics when magnetic phases undergo field-induced morphological changes. Supplementary Note 3 details other potential global achiral ground states, which possess distinct Bloch-line distribution and their anticipated Bloch-line reorientation to preserve their local chirality. Altogether, this empirical analysis demonstrates that in order to properly understand and describe local and global chirality effects in centrosymmetric magnets there is a need to consider the helicity of all magnetic spin textures stabilized at any field including their spatial arrangment to understand their local and global electrical and magnetic responses.

a–j Schematic illustration of the Block-line evolution for global a–e chiral and f–j achiral skyrmion lattice phases as perpendicular magnetic field is applied from negative to positive (left to right images) saturation. The right-handed (R) and left-handed (L) Bloch-line helicity is depicted with a black-hue arrowheads along the perimeter of red/blue-colored features which represent positive/negative perpendicular magnetic domains. A green-hue arrowhead depicts a Bloch-line whose helicity changed compared to prior applied fields. For each ground state, the local and global Bloch-line helicity distribution is depicted for both perpendicular magnetization textures. Local/global Bloch-line helicity is shown above/below the spin texture arrangement.

Conclusions

We have measured the transport properties of dipole skyrmions that form in Fe/Gd multilayer patterned wires through temperature- and field-dependent resistivity studies. By experimentally studying an Fe/Gd pattened wire with composition that primarily favors stripes at room temperature and a close-packed skyrmion lattice at low temperatures, we profiled the evolution of the transport signatures as a function of temperature and applied fields for three current-field geometries (parallel, transverse, and polar), which provided valuable insights about the dipole-stabilized magnetic spin textures and their three-dimensional arrangement. First, we confirmed stripe phases undergo continuos morphological transformations under applied fields, which are characterized by a representative parabolic-like resistivity response under perpendicular fields, while skyrmion lattice exhibit a parabolic-like resistivity response with a nontrivial anomaly. Field history studies revealed that the presence of a close-packed skyrmion lattice results in discontinuos microstructural changes in the domain morphology when transitioning between magnetic phases stabilized under opposite magnetic fields. Through micromagnetic simulations, we reproduced our experimental observations of an anomaly in the field-dependent polar longitudinal resistivity, and obtained detailed insights on the field-dependent evolution of complex three-dimensional magnetic spin textures. Micromagnetic simulations showed that the stripe phase undergoes a Bloch-line reorientation as the magnetic field is swept from one polarity to another, which enables the formation of an equal population of two helicity dipole skyrmions under negative and positive magnetic fields. Our results provide a strategy to aid the identification of materials capable of hosting dipole-stabilized skyrmion lattice phases, elucidate the mechanism by which dipole-stabilized skyrmions form in centrosymmetric magnets under applied perpendicular fields, and demonstrate how dipole-stabilized magnetic phases provide a distinctive testbed for studying interactions between local and global chirality effects.

Methods

Sample synthesis and device fabrication

The Fe/Gd films were prepared by DC magnetron sputtering by alternatively depositing Fe and Gd thin layers at room temperature using an Argon process gas pressure of 3 mTorr in a chamber whose base pressure was less than 1 × 10−8 Torr. A seed and capping layer of 5 nm Ta is used to protect the film from corrosion. The magnetic specimen exhibiting a close-packed skyrmion lattice from 180 to 100 K, of the form [Fe (0.36 nm) /Gd (0.4 nm)] × 80, is deposited onto a photolithography defined 8-bar Hall cross transport device on Si substrate with a 300 nm thermal oxide layer, and native-oxide Si substrate for magnetic characterization.

Transport characterization

Transport measurements were performed using the standard 4-point probe AC (~10 Hz) bridge technique with an applied current of I = 1 μA. The patterned wires have a length of 3.5 mm and width of 10 μm. Field-dependent longitudinal resistivity (ρxx) and Hall resistivity (ρxy) measurements were collected as the magnetic field was swept from positive to negative saturation and conversely, at discrete temperatures from T = 300 K to T = 20 K in 20 K steps; meanwhile, temperature-dependent ρxx measurements were collected at discrete temperatures from T = 300 K to T = 10 K in 2 K steps. We measure the ρxx in three different magnetic field configurations: (i) in-plane and parallel to the length of the wire (parallel, \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{||}}\)), (ii) in-plane and perpendicular to the length of the wire (transverse, \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{\perp }\)), and (iii) perpendicular to the film (polar, \({\rho }_{{xx}}^{{{\odot}}}\)). In our ρxx and ρxy measurements, the magnetic field is swept from H = +10 kOe to H = −10 kOe, and conversely.

Data availability

The data that support this work and the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Skyrme, T. H. R. A unified field theory of mesons and baryons. Nucl. Phys. 31, 556–569 (1962).

Nagaosa, N. & Tokura, Y. Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 899–911 (2013).

Kanazawa, N. et al. Large topological hall effect in a short-period helimagnet MnGe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 156603 (2011).

Schulz, T. et al. Emergent electrodynamics of skyrmions in a chiral magnet. Nat. Phys. 8, 301–304 (2012).

Huang, S. X. & Chien, C. L. Extended skyrmion phase in epitaxial FeGe(111) thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 267201 (2012).

Li, Y. et al. Robust formation of skyrmions and topological hall effect anomaly in epitaxial MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 117202 (2013).

Liang, D., DeGrave, J. P., Stolt, M. J., Tokura, Y. & Jin, S. Current-driven dynamics of skyrmions stabilized in MnSi nanowires revealed by topological Hall effect. Nat. Commun. 6, 8217 (2015).

Neubauer, A. et al. Topological Hall effect in the A Phase of MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 186602 (2009).

Matsuno, J. et al. Interface-driven topological hall effect in SrRuO3-SrIrO3 bilayer. Sci. Adv. 2, E1600304 (2016).

Kakihana, M. et al. Giant Hall resistivity and magnetoresistance in cubic chiral antiferromagnet EuPtSi. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 87, 023701 (2018).

Khanh, N. D. et al. Nanometric square skyrmion lattice in a centrosymmetric tetragonal magnet. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 444 (2020).

Liang, D. et al. Current-driven dynamics of skyrmions stabilized in MnSi nanowires revealed by topological Hall effect. Nat. Commun. 6, 8217 (2015).

Kadowaki, K., Onose, K. & Date, M. Magnetization and magnetoresistance of MnSi. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 51, 2433 (1982).

Chapman, B. J., Grossnickle, M. G., Wolf, T. & Lee, M. Large enhancement of emergent magnetic fields in MnSi with impurities and pressure. Phys. Rev. B 88, 214406 (2013).

Du, H. et al. Highly stable skyrmion state in helimagnet MnSi nanowires. Nano Lett. 14, 2026–2032 (2014).

Du, H. et al. Electric field probing of field-driven cascading quantized transitions of skyrmion cluster states in MnSi nanowires. Nat. Commun. 6, 7637 (2015).

Li, Z. et al. Phase selection in Mn–Si alloys by fast solid-state reaction with enhanced skyrmion stability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2009723 (2021).

Montoya, S. A. et al. Tailoriing magnetic energies to form dipole skyrmions and skyrmion lattices. Phys. Rev. B 95, 024415 (2017).

Montoya, S. A. et al. Resonant properties of dipole skyrmion in amorphous Fe/Gd multilayers. Phys. Rev. B 95, 224405 (2017).

Desauutels, R. D. et al. Realization of ordered magnetic skyrmions in thin films at ambiend conditions. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 104406 (2019).

Montoya, S. A. et al. Spin-orbit torque induced dipole skyrmion motion at room temperture. Phys. Rev. B 98, 104432 (2018).

Kittel, C. Physical theory of ferromagnetic domains. Rev. Mod. Phys. 21, 541 (1949).

Kooy, C. & Enz, U. Experimental and theoretical study of the domain configuration in thin layers of BaFe12O19. Philips Res. Rep. 15, 7 (1960).

Lin, Y. S., Grundy, J. & Giess, E. A. Bubble domains in magnetostatically coupled garnet films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 23, 485–487 (1973).

Cape, J. A. & Lehman, W. Magnetic domain structures in thin uniaxial plates with perpendicular easy axis. J. Appl. Phys. 42, 13 (1971).

Thiele, A. Theory of static stability of cylindrical domains in uniaxial platelets. J. Appl. Phys. 41, 1139 (1970).

Malek, Z. & Kambersky, V. On the theory of domain structure of thin films of magnetically uniaxial materials. Czech. J. Phys. 8, 416 (1958).

Kittel, C. Theory of the structure of ferromagnetic domains in films and small particles. Phys. Rev. 70, 965 (1946).

Meaden, G. T. Electrical resistance of metals. (Plenum, 1965).

Rüdiger, U., Yu, J., Thomas, L., Parkin, S. S. P. & Kent, A. D. Magnetoresistance, micromagnetism, and domain-wall scattering in epitaxial hcp Co films. Phys. Rev. B. 59, 11914 (1999).

Kent, A. D., Yu, J., Rüdiger, U. & Parkin, S. S. P. Domain wall resistivity in epitaxial thin film microstructures. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 13, R461 (2001).

Kent, A. D., Rüdiger, U. & Yu, J. Magnetoresistance, micromagnetism, and domain wall effects in epitaxial Fe and Co structures with stripe domains. J. App. Phys. 85, 8 (1999).

Ravelosona, D. et al. Domain-wall scattering in epitaxial FePd ordered alloy films with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 59, 4322 (1999).

Chang, R., Li, S., Lubarda, M. V., Livshitz, B. & Lomakin, V. FastMag: fast micromagnetic simulator for complex magnetic structures. J. Appl. Phys. 109, 07D358 (2011).

Heigl, M. et al. Dipolar-stabilized first and second order antiskyrmions in ferrimagnetic multilayers. Nat. Commun. 12, 2611 (2021).

Je, S.-G. et al. Direct demonstration of topological stability of magnetic skyrmions via topology manipulation. ACS Nano 14, 3251 (2020).

Acknowledgements

S.A.M. acknowledges support from the U.S. Department of Defense.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Project and experiment design was performed by S.A.M. Device fabrication and characterization were performed by S.A.M. Micromagnetic simulations and numerical analysis were performed by S.A.M., M.V.L., and V.L. The first draft of the text was written by S.A.M. All authors made contributions to the approved final text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Montoya, S.A., Lubarda, M.V. & Lomakin, V. Transport properties of dipole skyrmions in amorphous Fe/Gd multilayers. Commun Phys 5, 293 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-022-01073-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-022-01073-0

This article is cited by

-

Periodicity staircase in a centrosymmetric Fe/Gd magnetic thin film system

npj Quantum Materials (2024)