Abstract

This study delves into the relatively uncharted territory of Above Threshold Ionization in atoms, triggered by intense X-ray radiation fields. At these frequencies, the energy of a single photon far exceeds the ionization potential of valence electrons in atoms and molecules. The conditions we examine are similar to those achievable with current or future free-electron laser facilities. Under such high-energy scenarios, the onset of strong field ionization requires a shift away from the traditional quasi-classical approach. Here, we present an analytical model to characterize how the field-free ionization potential, ponderomotive energy, and photon energy govern the transition to this regime, all accounted for by means of the Keldysh and Reiss parameters. We show that both of these parameters are needed to capture the onset of strong-field behavior due to both bound state and continuum state properties. At higher X-ray intensities, we find that ionization rates deviate from the linear intensity scaling expected from lowest order perturbative processes, corresponding to channel closure and higher-order photon absorption processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The majority of X-ray absorption measurements conducted at X-ray Free-Electron Laser (XFEL) facilities have been satisfactorily explained using perturbation theory1,2, with a few notable exceptions3. With an advent of intense attosecond X-ray pulses4, we are led to an inquiry into the non-perturbative realm of strong-field phenomena at high frequencies. Previous experiments, though informative, may have fallen short due to factors such as inadequate intensity, prolonged pulse duration, signal contamination, and low signal-to-noise ratios.

Over the past decade, XFEL capabilities have been significantly enhanced. Techniques like X-ray Laser-Enhanced Attosecond Pulse Generation (XLEAP) at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray free electron laser have drastically reduced pulse duration, and the planned increase in repetition rate for LCLS-II further enables the detection of weaker signals4,5. As XFEL intensity increases further, a physical description of the strong-field limit becomes paramount.

This article embarks on an exploration of the strong-field regime of X-rays interacting with atoms through Above-Threshold Ionization (ATI), akin to analogous observations in the optical domain6. Our objective extends beyond delineating the boundaries of strong-field behavior for single-active electron processes; we venture into uncharted territory where conventional strong field intuition may falter.

Recent theoretical interest in ATI within intense X-ray radiation fields has grown. While early studies mainly focused on perturbative results7,8,9, there’s now a shift towards exploring ATI’s non-perturbative aspects. This includes using computational methods to understand multiphoton ATI in super-intense laser fields, especially in ultra-strong laser fields. The importance of relativistic effects, such as non-dipole effects and electron spin dynamics, is increasingly recognized10,11,12,13.

In our study, we introduce an analytical model that operates within the non-relativistic framework and the dipole approximation. This model provides a deeper understanding of the transition from weak to strong field ionization of atoms in terms of physical quantities. While our model disregards higher-order effects that are used in some numerical calculations, it still offers a clear physical interpretation of the process. Therefore, our analytical model serves as a valuable addition to the insights provided by numerical simulations.

Methods

Our study comprehensively delves into hydrogen-like applications, akin to treatments in refs. 14,15. It offers insights into the mechanisms underlying single-electron ionization and holds promise for elucidating emissions within the broader realm of single-active electron studies. Leveraging the foundational work laid out in ref. 16, we initially probe fundamental phenomena within a One-Dimensional (1D) spatial framework to bolster conceptual clarity, before encapsulating the key outcomes of our comprehensive Three-Dimensional (3D) theory. The path from weak-to-strong field emission is essentially the same in any number of dimensions. We will briefly outline assumptions and limitations of our model in the following subsection.

Assumptions and Limitations

This work deals with the intense X-ray regime, where the ejection of electrons can occur through the absorption of a single photon. We pay particular attention to the ponderomotive shift of the continuum17,18,19, focusing on laser intensities that are present before the initial closure of channels. The condition for this is given by

for monochromatic radiation where our work uses the Gaussian centimeter-gram-second unit system unless explicitly mentioned otherwise. In this equation, ℏω represents the energy of a single photon, expressed in terms of the reduced Planck constant ℏ and the angular frequency of the field ω. The field-shifted ionization potential, \({\tilde{I}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\), is decomposed into its field-free value Ip and a ponderomotive shift Up, which scales with the intensity I ≡ (c/8π)E2, where E is the electric field amplitude, ∣e∣ is the electronic charge magnitude, me is the mass of the electron, and c is the speed of light. This condition ensures that electrons are directly ejected into the field-shifted continuum, and the photons are sufficiently energetic to prevent populations from flowing into field-shifted Rydberg states. This limit encompasses a wide range of studies, including, but not limited to, the emission of individual electrons in a sequential ionization process20. For each subsequent ion, the closure condition must be recursively applied to its new binding energy.

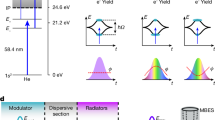

The current work focuses on processes similar to the type labeled (a) in Fig. 1. In these processes, the intensity I is less than the channel closure value I(cl), and the absorption of a single photon provides enough energy for an electron bound with energy \({\tilde{\varepsilon }}_{0}\approx -{I}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\) to overcome the field-shifted threshold \({\tilde{\varepsilon }}_{{{{\rm{thresh.}}}}}={U}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\). Processes of the type labeled (b) will not be discussed in this work. In these processes, the intensity levels exceed the closure value I(cl), causing the single-photon emission peak to shift below the ionization threshold. This shift reduces the ionization rate and enables populations to transfer from the ground state through AC-shifted Rydberg states of the atom21,22 during ionization. Furthermore, these dressed Rydberg states are power broadened by a characteristic scale ~ Γ and shift with the ionization threshold, as exemplified by \({\tilde{\varepsilon }}_{{{{\rm{Ryd.}}}}}^{(1,2)}\) in Fig. 1. This broadening can lead to the trapping of electrons in these states when the broadening of levels Γ is comparable in size to the spacing Δ between Rydberg levels. As these energy levels broaden, interference effects between different ionization pathways can occur, leading to the phenomenon of interference stabilization. In this phenomenon, an increase in field intensity results in a reduced ionization rate. Similar stabilization effects are discussed extensively in refs. 19,23,24,25,26,27,28.

a Illustrates the processes discussed in this work, where the intensity I is less than the channel closure value I(cl). b Shows processes not covered in this work, where the intensity exceeds I(cl). \({\tilde{\varepsilon }}_{{{{\rm{Ryd.}}}}}\) denotes the energy level of Rydberg states that shift with the ionization threshold. Superscripts 1 and 2 label separate Rydberg levels with energy difference Δ between them.

In this scenario, there is also a possibility for electrons to re-scatter off the atomic potential. Zhou et al.’s work, which is based on numerical solutions to the time-dependent Schrödinger equation (TDSE), illustrates that when the field intensity is less than the closure of the single-photon channel, direct electrons are ejected. This is evident from the emission features in Fig. 3(g) of their study10. As the intensity surpasses the closure point, it’s plausible that electrons re-scatter off the atomic potential. This could account for the observed plateau in the high-energy segment of the energy distribution, as shown in Fig. 3(h–i) in ref. 10, although the authors did not delve into the underlying mechanisms. Figure 3 panels (c), (f), and (i) in the same study display distinct low and high energy features. The yield of electrons at low energies rapidly diminishes, while those at high energies maintain a plateau. These characteristics mirror the behavior of direct and re-scattered electrons, akin to observations made in refs. 29,30,31 at long wavelengths.

Furthermore, we will investigate situations where the AC Stark shift of the ground state is small relative to its field-free value. This condition is given by

where the quiver length ξ ≡ ∣e∣E/meω2 associated with the oscillations of an otherwise free electron in an alternating field is smaller than or approximately equal to the effective Bohr radius of the target a0 under consideration given by \({I}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\equiv {\hslash }^{2}/2{m}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}{a}_{0}^{2}\). A precise discussion of these effects is given by refs. 22,32,33,34 for atomic hydrogen. Similar assumptions to ours have been applied in the conceptually similar ionization model of ref. 35 which ignores the AC Stark shift of the initial state in their discussion of electron emission by ultrahigh laser intensities in the visible to infrared spectrum. In high-frequency scenarios where ξ ≳ a0, dynamical or Kramers–Henneberger36,37 stabilization may occur. This phenomenon arises when the rapid oscillations of the laser field generate an effective binding potential, thereby decreasing the probability of ionization. This topic and specific criteria for the onset of this effect are detailed in refs. 19,26,38,39,40,41,42,43,44.

In the field-free system, we will assume motion described by a time-independent Hamiltonian for a scalar electron. Spin-orbit coupling, fine-structure, and other relativistic effects are all ignored. This limits our applications to light atoms and scenarios where spin-flip transitions are unimportant. Furthermore, the kinetic energy of ejected electrons needs to be at most about 1% of the 511 keV mass for ejected electrons to remain non-relativistic. Explicitly this condition is given by

and limits our non-relativistic approach to soft X-rays. Interesting features associated with the relativistic limit are discussed in refs. 45,46,47,48.

Finally, we assume that interactions between electrons and the field may be described within the dipole approximation. This applies additional constraints on our model. Emission in the weak-field X-ray limit is described by the absorption of a single photon by an initially bound electron. The interaction is localized to a region occupied by the initial bound-state density. If the wavelength λ of the radiation field is significantly larger than the Bohr radius a0 of a given target, then the entire electron cloud experiences essentially the same constant field in space. Processes discussed in this work satisfy

For hydrogen, the wavelength must be significantly larger than 0.053 nm or photon energies significantly less than 23 keV again limiting our application to soft X-rays. Our conclusions are supported with Fig. 3 of ref. 10. In this figure the authors give results where direct electrons in panel (g) (at an intensity preceding channel closure) agree with and without the dipole approximation. Contrastingly, the dipole approximation may not be applied to describe the plateau after the closure of channels as reported in panels (h) and (i). We speculate this to be the case since ejected electrons propagate in the continuum and re-scatter. The characteristic length-scale here is the quiver-radius ξ opposed to the Bohr radius a0. Here ξ becomes comparable to or may become larger than the wavelength λ inducing dipole breakdown conceptually similar to that discussed in ref. 49.

In the following subsections, we provide a comprehensive discussion of our model, including scenarios where it may or may not be applicable.

Preliminary model discussion

Our immediate aim is to identify the onset of the strong-field regime in X-ray radiation and discern its similarities and disparities compared to the analogous strong-field limit encountered in low-frequency fields. To achieve this, we will initially focus on the photo-ionization of a single electron in a one-dimensional setting, allowing us to disentangle target-dependent and target-independent aspects of ionization. The non-perturbative scaling laws identified in this context serve as a foundation for generalization to three dimensions. Despite potential variations in specific details, the overarching conclusions remain consistent.

Our approach involves rigorously integrating the Keldysh amplitude to ensure alignment with numerical solutions of the TDSE. The model follows the same methodology as described in ref. 50 and is akin to the one-dimensional model presented in ref. 16, with the inclusion of the long-range atomic potential and replacement of the saddle point approximation by full time integration.

In this study, we employ final continuum states represented by approximate atom-Volkov states. These states are particularly suitable for single photon energies that surpass the ionization threshold, once adjusted for AC effects. The first-order diagram from ref. 51, which has been utilized in several other studies50,52,53,54,55, simplifies to the scenario depicted in ref. 56 when applied to atomic hydrogen in the length gauge. The compatibility of our model with the TDSE for ATI initiated by strong extreme ultraviolet radiation fields is demonstrated for direct electrons in Fig. 1 of ref. 56.

Our detailed treatment of long-range potentials is discussed in the following subsection.

Ionization of electrons bound by long-range potentials

Our model, as derived in refs. 50,51, is based on an approximate solution of the TDSE:

Here, a (scalar) electron initially bound to a level of the atomic Hamiltonian

interacts with an applied laser field through the interaction VL(x) ≡ ∣e∣E(t) ⋅ r in the length gauge where E(t) is the electric field. Here Va(r) is the atomic potential, pop ≡ − iℏ ∇ is the momentum operator and the variable x ≡ {r, t} represents the combined position r and time t coordinates, with r considered in either one-dimensional or three-dimensional space.

An exact solution to this problem is provided by the time-dependent version of the initial-state Lippmann–Schwinger equation57,58:

Here, ϕ0(x) represents the initial electronic state of the atomic Hamiltonian prepared at time t = 0, before the laser field is applied. The second term accounts for electrons “ionized" from the coordinate xi within the ground-state density due to the laser interaction VL(xi) which represents the absorption (emission) of a single photon. The Green’s function (propagator) G(x; xi) describes the electronic motion from the ionization location xi to the detector at a location x (t > ti), illustrating how electrons leave the atom.

The standard perturbative approach

Typically, photo-ionization by weak X-ray radiation fields involves the absorption of a single photon. The propagation of ejected electrons is described by:

where horizontal lines above symbols represent the complex conjugate. This equation represents the motion of ejected electrons within the continuous spectrum of the atomic Hamiltonian. During the electron’s propagation from the ionization location xi within the ground-state density to a location x at the detector, the atomic potential is treated exactly. The laser field is completely ignored during this propagation. The states \({\phi }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(-)}(x)\) of the continuous atomic spectrum have asymptotic momentum ℏk at the detector (either in 1D or 3D) and are asymptotically equivalent to a plane wave plus an ingoing spherical wave at r → ∞15,59. Complex ionization amplitudes (photo-electron distributions) are derived from the expansion coefficients of the approximate wave function with respect to each momentum state \({\phi }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(-)}(x)\).

For stronger fields, which result in subsequent photon absorption processes (see refs. 60,61), the propagation of an ejected electron is instead described recursively. This procedure is represented by the Lippmann–Schwinger equation as:

Here, Ga(x; xi) contains both continuous and discrete spectra of the atom, and the coordinate \({x}^{{\prime} }\) may be interpreted as an instant where higher-order photon absorption or emission processes occur. If \({V}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}({x}^{{\prime} })\) is relatively small, then few iterations may be required. However, this procedure will not converge for any finite order in the non-perturbative strong-field limit (see refs. 62,63). Therefore, an alternative strong-field approach is required.

The standard non-perturbative approach

For “short-enough" range potentials (see discussion in ref. 50), the non-perturbative emission of electrons is typically described as

in length-gauge16,50,64 with complementary velocity-gauge models described in refs. 62,65 and examples of relativistic generalizations discussed in refs. 66,67.

In this context, the so-called length-gauge (Gordon-)Volkov states68,69 are given by:

in D − dimensional space. These states describe the exact propagation of an electron in the field. During the propagation from the ionization location xi to the detector x, the atomic potential is neglected. This approximation is valid for emission processes where electrons, bound by short-range potentials (such as anions), are ejected by long-wavelength radiation fields. In such scenarios, the ionization locations ri are far from the nuclear center, allowing the atomic potential to be neglected. Consequently, the electronic trajectories are determined solely by the field. This conclusion is supported by Equations (B7) and (C5) of ref. 50, which show that ionization locations are suppressed near the nuclear center for strong fields (large quanta) and dominate near the nuclear center for weak fields (few quanta). The dominance of the asymptotic “tail” of the ground state density in ionization at long wavelengths is further discussed in ref. 16. The electron-laser interaction VL(xi) described in Eq. (7) represents the initial absorption (or emission) of a single photon, which initiates the dynamics. All higher-order photon processes are inherently included in the time-dependence of the Volkov state (Eq. (11)). Ionization amplitudes, similar to those in perturbative theory, are derived from the expansion coefficients corresponding now to each canonical momentum state Φk(x) of the electron in the field.

These states are expressed in terms of the classical action

of a liberated electron and are determined from the kinetic momentum

of an electron in the field where ℏk represents the canonical momentum and A(t) is the vector potential which is related to the electric field by E(t) = − (1/c)∂tA(t).

This approximation becomes inadequate when considering shorter-wavelength radiation fields, where ionization locations may reside closer to the nuclear center, and the “trajectory" of ejected electrons is influenced by the atomic potential. Figure 2(c) of ref. 50 presents ionization yields for an electron bound to the ground state of a short-range Yukawa potential. The green curve represents emission where the atomic potential is ignored in the propagation of ejected electrons post-ionization. While this model provided accurate results at the longest infrared wavelengths considered, it overestimated yields compared to results of the TDSE at shorter X-ray and ultraviolet wavelengths.

An attempt to correct trajectories post-ionization at shorter wavelengths involves utilizing the Lippmann–Schwinger equation58,70:

Here, GV(xr; xi) describes the trajectories of electrons in the field that re-scatter off the atomic potential Va(rr) at a location rr and time tr. This recurrence relation represents the exact motion of liberated electrons. However, in practice, it is only approximate, as it is recursively applied finitely many times to describe re-scattering events. This is not an issue for short-range potentials, from which electrons may eventually escape. Diagrammatic approximations similar to this have been applied early on in the work of refs. 71,72,73,74,75,76,77 with varying degrees of accuracy depending upon the specific application. In the absence of a field, this is identical to the Born approximation where plane-wave electrons scatter off an atomic potential78,79,80. Scattering amplitudes of this type, present for long-range potentials and relevant for neutral atoms and the majority of systems under investigation, are generally divergent, and the procedure is not necessarily valid81,82,83,84.

The diagrammatic expansion is often avoided altogether in long-wavelength situations, where the quasi-classical approximation is instead applied to modify the Volkov states to include the Coulomb potential in ionization, as discussed in refs. 85,86,87,88. Unfortunately, the use of the saddle point approximation and other quasi-classical approximations used in these works makes these models inapplicable to the present application of ionization by strong X-ray radiation fields. A comparison of “exact" and saddle-point results given in Fig. 1 of ref. 50 (for short range potentials) shows agreement for emission driven by long-wavelength infrared radiation fields and disagreement for emission driven by short-wavelength X-ray and ultraviolet fields. Ionization by free-electron lasers requires an alternative description.

The atom-Volkov approach utilized in this article

In perturbative photon absorption processes (Eq. (9)), the propagation of liberated electrons is treated exactly, while the absorption of photons is considered as a higher-order correction. In contrast, the standard strong-field approach treats the propagation of the removed electron in the field exactly, with the atomic potential introduced through perturbative corrections involving re-scattering (Eq. (18)). Both approaches are valid in the limit of weak interactions. However, in practice, the former fails for strong fields, and the latter fails for long-range Coulomb potentials. These limitations are relevant to the application under investigation.

We seek states that accurately represent the propagation of liberated electrons within the atomic potential at short distances, where the field is of lesser importance, and at long distances, where the acceleration of liberated electrons in the field is more significant than the atomic potential. Therefore, we need a method that can effectively address both limits, which would require determining an exact solution to the TDSE of Eq. (5), for which there is no known analytic solution. To overcome this limitation, we instead utilize alternative (approximate) atom-Volkov continuum states:

as described in refs. 50,51,52,53,54,55. This ansatz replaces the plane-wave present in the “standard" Volkov states of Eq. (11) with scattering states of the atomic potential \({\phi }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(-)}({{{\bf{r}}}})\). At large distances (r → ∞), atomic continuum states become increasingly similar to their plane-wave counterparts. In this limit, atom-Volkov states tend towards the exact propagation of electrons in the field. These states become approximate near the nuclear center, where electronic motion is influenced by both the atomic forces and the applied laser field.

To further understand these states, we can consider the perturbative weak-field limit. If this approximation is valid, these states should reduce precisely to the perturbative single-photon result discussed earlier. In the limit where the field amplitude is set to zero, the atom-Volkov states should converge exactly to the atomic continuum states \({\phi }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(-)}(x)\).

Taking the weak-field limit, we obtain:

which immediately yields the desired result:

where εk ≡ ℏ2k2/2me is the energy of liberated electrons with asymptotic momentum magnitude ℏk. The atom-Volkov approach exactly describes the motion of liberated electrons in fields of any strength when the electrons are far from the residual ion, as well as throughout all of space in the weak-field perturbative single-photon limit. The approximation lies in the strong-field limit at positions near the atomic center. The scattering state \({\phi }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(-)}({{{\bf{r}}}})\) approximates how an electron couples to the atomic continuum and higher-order photon absorption processes are approximated by the time-dependent phase-factors contained in the ansatz given by Eq. (15).

The deviation between the exact and approximate propagation of liberated electrons within the model is described by the Lippmann–Schwinger equation:

This equation describes the exact emission of liberated electrons in terms of scattering processes involving atom-Volkov states (refs. 51,52,53,54,55). When iterated finitely many times, it corrects the approximate atom-Volkov propagation of electrons, described by GaV(xs; xi), with scattering processes off an effective potential VaV,op(xs). Our particular application focuses on situations where all higher-order scattering processes represented by the integral contained in the equation above may be neglected.

The approach is valid in situations where the action of VaV,op(x) on the atom-Volkov propagator:

results in a small quantity, indicating that electrons weakly scatter off the potential. This expression includes both the continuous spectrum of states \({\Phi }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(-)}({{{\bf{r}}}})\) discussed earlier and an additional discrete spectrum:

While these discrete states are not considered in our discussion of direct electron emission by X-ray photons, they are useful for evaluating scenarios where the matrix elements of VaV,op(x) are small, allowing the model to be applied. These states are related to the bound states of the atomic Hamiltonian \({\phi }_{j}(x)={e}^{-({{{\rm{i}}}}/\hslash ){\varepsilon }_{j}t}{\phi }_{j}({{{\bf{r}}}})\), with the action given as:

These states could potentially approximate the AC-shift of Rydberg levels (the time average of the second term is Up for a monochromatic field), but it does not satisfactorily describe the AC-shift of the ground state, as discussed in ref. 53. Modifications to this model are required in such situations.

Differentiating the Green’s function with respect to time yields the relation:

where the approximate atom-Volkov Hamiltonian is given by:

Here, we have utilized a momentum operator:

which subtracts off the vector-potential contribution in length gauge. An additional operator πop is defined which extracts the asymptotic momentum of a state, defined on bound and continuum states as:

whose spectra describes the momentum of liberated electrons at a moment where the laser field is turned off and at a position asymptotically far from the atomic center. The resulting “scattering" potential is therefore obtained as the difference between the exact and approximate atom-Volkov Hamiltonians:

which may look strange, but has a simple physical interpretation. It quantifies the significance of the atomic potential Va(r) through the deviation of states \({\Phi }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(-)}(x)\) from “zero-range" states determined in a limit where Va(r) → 0.

The conventional approach utilized by Keldysh applied plane-wave Volkov states, which is exactly the “zero-range" limit of the current atom-Volkov approach under consideration. We will therefore investigate scattering processes in an application where the atomic potential is of such short range that it may be negated after ionization. Scattering processes here are obtained from matrix elements of the interaction VaV,op(x) with respect to the Volkov states Φk(x). Interestingly, these interactions vanish completely. This can be most easily observed from the action of the momentum difference operator Δpop(t) and the asymptotic momentum operator πop on the states separately. Specifically, we have:

This result arises from the fact that Φk(x) is proportional to a plane-wave with momentum-vector ℏk + (∣e∣/c)A(t). This is exactly the same result obtained from the application of the asymptotic momentum operator in Eq. (25). This result should not be surprising. If there is no atomic potential, then there is also no re-scattering, as seen earlier in Eq. (18). The operator πop reads off the asymptotic momentum of liberated electrons where the field is neglected, while the momentum difference Δpop defines a momentum operator that has been shifted by the field. For plane-wave Volkov states, these quantities are identical, but they differ in general for atom-Volkov states \({\Phi }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(-)}(x)\).

In our initial discussion of atom-Volkov states, we mentioned that the present result becomes exact in the weak-field limit for scattering states \({\phi }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(-)}({{{\bf{r}}}})\) determined from any potential. This is evident from the fact that in the single-photon weak-field limit, as A(t) → 0, so does VaV,op(x). However, how can we justify the method for the present case of strong-field electron emission from atoms bound by long-range forces? To address this, we will act on general atom-Volkov states with the interaction VaV,op(x) and observe situations where this quantity may or may not be significant.

When acting on the atom-Volkov states with the interaction, we obtain:

with similar expression obtained for the dressed bound-states Φj(x) when the limit (ℏk) → 0 is taken. Scattering is unlikely at locations where r → ∞ because the local momentum of electrons, determined from pop, tends towards its asymptotic value ℏk15. In contrast, the momentum of electrons may differ from its asymptotic value at locations near the nucleus. The interaction is nearly identical to the perturbative single-photon matrix element, but with additional phase factors when acting on Φj(x), allowing for the transfer of additional quanta. Similarly, the continuum-state matrix elements mirror the perturbative result, with the operator pop replaced by pop − (ℏk) and similar phase factors.

Plotting hydrogenic states from ref. 15 shows that energetic electrons are described by continuum states that tend towards their asymptotic plane-wave limits closer to the atomic center than slow electrons, which are closer to the ionization threshold in energy. This suggests that the matrix elements of the interaction VaV,op(x) become negligibly small not only when electrons are asymptotically far from the ionized atom, but also at any location in space at high-energy limits, where fast electrons are significantly above the ionization threshold in energy.

A characteristic value of this energy scale can be obtained from the atomic Hamiltonian in Eq. (6). The present approximation is most valid when the kinetic energy is larger than the atomic potential. A characteristic value for the former is εk, and for the latter is Ip. We aim for εk ≳ Ip to ensure the approach is most accurate in the strong-field limit. Alternatively, we can express the condition as ka0 ≳ 1, where a0 is the effective Bohr radius as before.

This criterion should ensure that the quantity defined in Eq. (28) remains relatively small. It should be taken as a rule of thumb rather than an exact criterion, as the method aligns with accurate solutions of the TDSE for photoionization, where the lowest-order emission peak falls within this window, as shown in refs. 50,56. This criterion may become more significant in the ultra-strong-field limit due to the proportionality factor of A(t) within VaV,op(x).

Finally, the complex ionization amplitude and resulting photo-electron distributions are determined from the initial-state Lippmann–Schwinger equation in Eq. (7). In this context, the approximated state Ψ(x) is obtained by approximating the propagation of liberated electrons using the atom-Volkov states from Eq. (15). The amplitude

is determined by projecting \({\Phi }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(-)}(x)\) onto the approximate state Ψ(x). This form is similar to both that of perturbation theory and the original work of Keldysh64.

To further refine this model, we integrate by parts and express it in an alternative form:

Here, the contribution

describes how liberated electrons exit the ground state. The shifted action

is defined to simplify results.

Areas of model weakness

The primary limitation of the model is its focus on a first-order transition between a single discrete state and the continuum. Our formulation effectively characterizes electrons that are ejected from the ground state into the AC-shifted continuum. However, it does not account for multiphoton transitions that may involve an intermediate resonance or re-scattering. Additionally, higher-order transitions (radiative scattering) between atom-Volkov states are possible, even with photons that possess energy exceeding the field-shifted threshold \({\tilde{I}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\). The atom-Volkov states utilized in our work are essentially exact in the asymptotic limit as r → ∞, but neglect part of the laser interaction and exhibit distortion near the atomic center. Errors may be introduced in the lowest-order approach for slow electrons near the ionization threshold (ka0 ≲ 1), as discussed in the prior section. Additionally, the atom-Volkov wave-function ansatz of Eq. (15) utilizes field-free states of the atomic Hamiltonian \({\phi }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(-)}({{{\bf{r}}}})\). This may become suboptimal in applications involving both high frequencies and ultra-high intensities after the onset of dynamical stabilization effects, where distorted states of the Kramers–Henneberger Hamiltonian could possibly form the basis of a new wave-function ansatz. In this work, we will assume that these effects are secondary and may be disregarded. The rationale for this assumption is provided in the following paragraph. However, these effects may become significant for near-threshold (low-energy) continuum states in extremely strong fields, particularly when the quiver radius ξ is approximately equal to or larger than the Bohr radius a0 of a specific atom. This underscores the complexity and nuances of the phenomena under study.

In Fig. 2 of ref. 50, the model was compared with TDSE emission results for a Yukawa potential with a large decay parameter, representing a zero-range system. The range was systematically increased until it reached the hydrogen-like case, at a fixed ionization potential, Ip. The model was accurate in both the tunneling and single-photon limits for all decay parameters before the emergence of an excited state. The breakdown for hydrogen was due to the formation of excited states in the atomic spectrum. The yield was accurately represented for photons with enough energy to eject electrons with a single quantum, but the yield was underestimated once two or more photons were needed to overcome the AC stark shifted ionization threshold.

Our interpretation of these results is further supported by potentials of intermediate range, which only support a finite number of excited states. In ref. 89, the authors conducted a more detailed analysis of the numerical results from Fig. 3(c) of ref. 50. A Yukawa potential, serving as a short-range analog of neon and containing a highest allowed 2p excited state, was studied. This was selected to match the valence of the model potential. Reference 50 reported the total yield due to the sum of all orbitals, while ref. 89 examined these contributions individually. It was found that single-active electrons initially bound to the 2s state of the potential were accurately represented by the model in both the single-photon and tunneling ionization limits. However, a deviation between our model and the TDSE was observed in the two-photon spectrum. The enhanced emission observed in the numerical results of the TDSE was absent from our model at wavelengths localized near the 2s-2p transition energy. Interestingly, when prepared in a 2p excited state, we observed diminished emission exactly at wavelengths within this window. Notably, these contributions canceled each other out in the cumulative results of the combined orbitals from ref. 50. The resonant-enhancement of the initial 2s state offset the suppression in emission from the 2p state. The model results provided quantitative agreement with the TDSE for the summed yield, even at wavelengths at the 2s-2p transition energy.

It is speculated that the inclusion of higher-order diagrams defined in the prior subsections and discussed in refs. 51,52,53, should be considered to describe processes which require either the inclusion of intermediate bound states or re-scattering of electrons off of the atomic potential. However, these higher-order processes are beyond the scope of the current work. In this study, we focus solely on a leading-order description of direct electrons.

Calculation of ionization rates

We will now describe results of our model in a single dimension. An identical three-dimensional derivation of these results, tailored to the case of linear polarization, is provided in the “Supplementary Note 1: Three-Dimensional Emission" section of the Supplementary Information. This format allows for a direct comparison with the present one-dimensional outcomes.

Here, the vector potential is given by

and emission in 1D, along the z-axis, is characterized by the complex probability amplitude given by (Eq. (30)),

which describes contributions to ionization due to intermediate “ionization times” ti for a given final momentum, ℏkz.

The classical action in Eq. (34) is given by,

where pz(t) is the kinetic momentum given by,

Equation (34) includes:

where a line over symbols is used to represent the complex-conjugate and ϕ0(zi) is the time-independent bound state, which is given in 1D by:

where r ≡ ∣z∣ represents the radius, \(\hat{r}\equiv \,{\mbox{sign}}\,(z)\) is a unit vector, and “linear harmonics” are defined as:

depicting states of even parity l = 0 and odd parity l = 1.

The \(\overline{{\phi }_{{k}_{z}}^{(-)}({z}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}})}\) in Eq. (37) can be obtained from the continuum-state wave-function,

where k ≡ ∣kz∣ describes the momentum of ejected electrons in the direction \(\hat{k}\equiv \,{\mbox{sign}}\,({k}_{z})\), and \({Y}_{{l}_{k}}(\hat{k})\) is defined in Eq. (39). Radial functions \({R}_{{k}_{z},{l}_{k}}(r)\) of even and odd parity are introduced through a partial-wave decomposition of the atomic scattering states similar to refs. 15,59. The radial functions \({R}_{k,{l}_{k}}(r)\) are determined numerically from the atomic Hamiltonian and \({\eta }_{{l}_{k}}({k}_{z})\) are scattering phase shifts determined numerically from the asymptotic expression

with Sommerfeld parameter η ≡ − Zion∣e∣2/ℏv, mev ≡ ℏk and a k − space normalization convention.

The time-dependent part of Eq. (37) (that incorporates the effect of the vector potential) can be expanded using the Jacobi-Anger expansion62,90,91

with ℏkA ≡ ∣e∣E/ω defined as the vector potential momentum amplitude. \({e}^{-i{n}_{A}\omega {t}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}}\) represents an energy transfer − Ip ↦ − Ip + nAℏω from the field to the electron (in the long pulse limit).

We further note that the field interaction is introduced in Eq. (42), with the amplitudes in the expansion given by,

which represents spatial contributions of even and odd parity with lA ≡ mod(nA, 2) for each photon process nA. During this step \({Y}_{{l}_{A}}({\hat{r}}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}})\) represents a parity transfer l0 ↦ mod(l0 + lA, 2) from the radiation field to the atom and should be interpreted as a one-dimensional analog of the angular momentum transfer.

Plugging Eq. (42) into Eq. (37) and taking a time-derivative, we obtain,

We now use Eq. (40), which gives the expression for \({\phi }_{{k}_{z}}^{(-)}({z}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}})\), take its complex conjugate, and plug it into the above equation, also substituting ϕ0(zi) from Eq. (38). We obtain,

where the integral

represents how strongly some momentum ℏk is weighted for a given kA and nA due to initial and final states of a particular atomic target and the directional dependence

represents the multiphoton selection rule lk = mod(l0 + lA, 2) and is valid for initial states of definite parity. This is similar to the addition of angular momentum in three dimensions. Note that the quantity \({I}_{{l}_{k},{l}_{0}}^{({n}_{A})}(k,{k}_{A})\) contains all information about contributions to ionization dependent on the initial bound and continuum states R0(ri) and \({R}_{k,{l}_{k}}({r}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}})\) respectively.

To complete our evaluation of Eq. (34), we will now turn to the action integral, S(kz, ti), given in Eq. (35). Plugging Eqs. (33) and (36) into Eq. (35), using \({\hslash }^{2}{k}_{z}^{2}/2{m}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}={\varepsilon }_{k}\) (the field-free energy), and the trig identity \({\sin }^{2}\theta =(1-\cos (2\theta ))/2\), we obtain after integrating,

where the function ξz(t) is given by \({\xi }_{z}(t)\equiv \xi \cos (\omega t)\), with ξ ≡ ∣e∣E/meω2, and characterizes the quiver motion of the free electron induced by the external field. Furthermore, Reiss’s parameter \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\), is given by \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\equiv {U}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}/\hslash \omega\)62, where Up ≡ ∣e∣2E2/4meω2 corresponds to the cycle-averaged quiver (ponderomotive) energy of the field. The continuous parameter N(k), defined by \(N(k)\equiv ({\varepsilon }_{k}+{\tilde{I}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}})/\hslash \omega\), acts as a gauge for the number of photons with energy ℏω required for an electron to surpass the field-shifted ionization potential \({\tilde{I}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\), thus facilitating its propagation and attainment of a field-free energy level εk. Here, \({\tilde{I}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\) is represented as \({\tilde{I}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\equiv {I}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}+{U}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\).

Note that \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\) in the above equation serves as the continuum-state intensity parameter, providing insights into the non-perturbative characteristics of the system and essentially reflecting the number of photons “contained” within the ponderomotive shift of the continuum. Values \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\, \gtrsim \, 0.1\) are typically associated with non-perturbative emission.

We now plug Eqs. (45) and (48) into Eq. (34). Grouping all the time-dependent terms inside the time-integral over ti, and using the Jacobi-Anger expansion (such as was done in Eq. (42)) for the trigonometric functions in S(kz, ti), we get

with n ≡ nA + nS + 2a and parity lS ≡ mod(nS, 2).

The golden-rule-like quantity92

describes the distribution of final energy states after the absorption of nA + nS + 2a photons by a finite flat-top pulse. Contributions to ionization discussed here are present in all ionization events regardless of the particular choice of atomic target. In the “Continuum-State Distortions" subsection of the Results section we will systematically investigate this quantity to show the emergence of strong-field effects due to propagation of otherwise free electrons in the alternating electric field.

Using results in Eqs. (45) and (49), the complex ionization amplitude in Eq. (34) becomes,

where the total yield is given by

if t is assumed to be the end of the pulse.

Taking now the long pulse limit t → ∞ and utilizing the sinc representation of the Dirac delta distribution we have the photo-electron momentum distribution

with \({k}_{z}={k}_{n}\hat{k}\) and partial contributions

for each photon process. Here \(\hslash {k}_{n}=\sqrt{2{m}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}(n\hslash \omega -{\tilde{I}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}})}\equiv m{v}_{n}\) defines the final momentum of ejected electrons with nS ≡ n − nA − 2a and lS = mod(n − nA, 2). We have applied the addition of parity \({Y}_{{l}_{S}}(\hat{k}){Y}_{{l}_{k}}(\hat{k})=(1/\sqrt{2}){Y}_{{l}_{n}}(\hat{k})\)15 with ln ≡ mod(lk + lS, 2) = mod(l0 + n, 2).

Integrating over kz yields the total ionization rate

with partial contributions \({w}_{n}(\hat{k})\equiv | {{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}_{n}(\hat{k}){| }^{2}.\)

Similar results are typically written in the form

where the generalized Bessel functions93

have been introduced.

In this section, we’ve divided the ionization amplitude into two parts. The first part is attributed to the specific wave-function of the ground and continuum states, while the second part is due to the propagation of a free electron in a dynamic electric field. Moreover, we’ve expressed our final result using the generalized Bessel function \({J}_{n-{n}_{A}}(\cdot ,\cdot )\)62,93. This representation facilitates a comparison of our findings with the conventional long-wavelength limit and will be discussed within the “Characteristic Behavior" subsection of the following Results section.

It’s important to note that both high and low frequency fields can trigger strong-field ionization. However, the phenomenon of tunneling is exclusive to low frequencies.

Results

Building upon the analytical model derived in the previous section, we now turn our attention to its practical application. We explore a one-dimensional version of hydrogen to demonstrate the onset of above-threshold ionization with respect to laser intensity. The initial bound electron, belonging to the 1s − state (l0 = 0, Ip ≈ 13.6 eV) of the atom, corresponds to the potential

and is ejected into a set of discrete energy levels \({\varepsilon }_{k}\equiv {\hslash }^{2}{k}_{n}^{2}/2{m}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}\). Emission at each energy is due to a single channel l of definite parity.

Above-threshold ionization

Our focus is on the emission of direct electrons by fields that contain photons with energies of 125 eV and 250 eV. We study these fields at intensities ranging from 1010 W/cm2 up to their respective channel closures I(cl), as illustrated in Table 1. For context, we also include closure values for fields with photon energies of both 500 eV and 1000 eV.

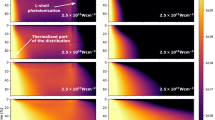

The results of this study are depicted in Fig. 2. Panels (a–c) correspond to a photon energy of ℏω = 125 eV, while panels (d–f) are associated with ℏω = 250 eV. Panels labeled (a) and (d) display the total ionization rate (blue line) for a given intensity I. In weak fields, the rate shows a linear relationship with intensity, denoted as w ∝ I, which is represented by the dashed line (black). This is indicative of the lowest-order perturbative behavior. However, a significant deviation from this linear scaling is observed once the intensity exceeds I ≈ 1015 W/cm2 in both cases.

Results of strong-field ionization by X-ray drivers at 125 eV (a–c) and at 250 eV (d–f). Panels a and d indicate the total ionization rate w (blue line). Panels b, e and c, f give partial rates into each ATI peak as a heat map, where b, e is on a log scale and c, f is on a linear scale. Additional dashed black lines indicate w ∝ I scaling in a, d and εk ∝ Up scaling in b, e. Vertical lines are included for intensity parameters at \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}=0.1\) (light blue) and \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}=0.1\) (green). The vertical pink line labeled T1/2 = 50 as corresponds to a limit where 50% of the ground-state is depleted after 50 as. For 125 eV this curve is located behind the \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}=0.1\) mark.

A vertical line (pink), labeled T1/2 = 50 as, is included to indicate an intensity level where 50% of the initial ground-state population is depleted after 50 as. This specific value is chosen to align with the duration of the shortest pulses produced in experiments to date94,95,96,97.

To observe substantial strong-field behavior, it’s necessary for the pulse to rise rapidly and for the depletion of the ground state to be minimized. A time-dependent analysis of the problem, which includes ground-state depletion and the pulse profile, should be considered for intensities that are similar to or exceed the T1/2 = 50 as mark. It’s likely that atomic populations would deplete before electrons have a chance to experience the true peak intensity of the field, which may prevent the observation of strong field behavior. However, this won’t be an issue in the full three-dimensional theory. While one-dimensional models are a useful tool for gaining intuition, it is observed that they greatly overestimate rates and strong field effects.

In the panels labeled (b) and (e) for both fields, we have broken down the total ionization rate into individual contributions from each ATI peak, represented as \({\varepsilon }_{k}={\hslash }^{2}{k}_{n}^{2}/2{m}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}\), on a logarithmic scale. For fields with intensities less than approximately 1015 W/cm2, the emission process of the lowest order n = 1 predominates, with the rate scaling as w ∝ I. However, at higher intensities, the rate deviates significantly from this linear behavior, coinciding with emissions due to higher ATI orders n > 1. For comparison, we have included a dashed line (black) corresponding to εk ∝ Up, which indicates an approximately linear scaling of the ATI cutoff energy with respect to field intensity.

Emissions occurring near the conditions of channel closure are illustrated in panels labeled (c) and (f), which are displayed on a linear scale. A multitude of ATI orders are evident. The oscillatory behavior of Bessel functions, inherent within the strong-field amplitude with respect to intensity, is responsible for the beating observed within an individual ATI order n. It’s noteworthy that single-photon ionization has the potential to be non-perturbative, provided the field intensity can be escalated rapidly enough. In the following section we investigate this transition from weak to strong field behavior.

Intensity parameters

We can refine the characterization of the previous numerical outcomes by employing dimensionless intensity parameters, each delineating the onset of strong-field ionization. One parameter addresses distortions in the ground state, while the other addresses distortions in continuum states62,64.

Continuum-state distortions

Let’s begin with the non-perturbative continuum-state intensity parameter discussed earlier, denoted as \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\), defined by the ratio Up/ℏω. This parameter becomes significant when \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}} \, \gtrsim \, 1/10\), indicating that the shifts in ATI peaks (Up) are substantial compared to the energy spacing (ℏω). Conversely, when \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\ll 0.1\), the effect of the AC shift on the continuum is negligible compared to the photon energy. Consider, for instance, a Ti-sapphire laser operating at a wavelength of 800 nm and an intensity of 1014 W/cm2. In this case, we find that \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\approx 4\), which signifies a significant deviation from the weak-field limit. Our study is primarily focused on XFEL lasers operating below the first channel closure. It becomes clear that \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}} \, < \, 1-{{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{0}\), where \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{0}\equiv {I}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}/\hslash \omega \, < \, 1\). This condition guarantees that \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\) always remains less than 1. The distortion in continuum states is significantly less than the previous example at long wavelengths. In Table 1, we present the values of the intensity parameter at the closure intensity I(cl) for various photon energies ℏω.

The dependence of the generalized Bessel function \({J}_{n-{n}_{A}}({k}_{n}\xi ,-{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}/2)\) on \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\) is evident in the strong-field amplitude. When we move sufficiently far from the channel closure (\({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\to 0\)), we can apply the limit98

to simplify to

Here, a = 0 corresponds to the weak-field limit, while a ≠ 0 signifies strong-field effects due to electron motion within the continuum.

Similarly, as \(k_n\xi = 2\sqrt{2{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}(n-{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_0-{{{\mathcal{Z}}}})}\mathop{\longrightarrow}^{{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\ll 1} 2\sqrt{2{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}(n-{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}_0)}\), we find

with weak-field contributions when nA = n, and strong-field contributions when nA ≠ n.

As the parameter \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\) approaches zero, the expression for \({{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}_{n}(\hat{k})\) simplifies significantly:

In this equation, the effects of strong fields, which originate from continuum propagation, are eliminated. By investigating additional values of a and nA that are adjacent to their weak-field counterparts, we can measure deviations from weak-field predictions.

The expression in the equation above (dashed line) has been compared with the earlier results (solid line) in Fig. 3 at 125 eV. This comparison demonstrates agreement far from the channel closure and the emergence of deviations as the closure is approached. Panel (a) shows a quantitative agreement between weak-field and numerical results of the total rate. In contrast, panel (b) reveals a similar agreement for partial rates corresponding to the first two ATI peaks at low intensities but significant discrepancies at high intensities. The oscillatory behavior of partial rates at high intensity is due to a departure from our lowest-order weak-field analysis. The Bessel functions contained within the rate oscillate with intensity, indicating a departure from the lowest-order polynomial behavior typically observed in a weak field.

Results of Fig. 2 represented differently. a Shows the total rate w (blue line) and two additional approximations. The first (w, dashed pink line) corresponds to Eq. (62) and second (vw, dotted black line) corresponds to this approximation combined with the further approximation of Eq. (64). In panel b we have plotted these same quantities, but now for the partial rates w1 and w2. The solid blue (red) line corresponds to the partial rate w1 (w2), the dashed pink (black) line corresponds to the approximation of Eq. (62) for w1 (w2) and the dotted pink (black) line corresponds the the approximation of Eq. (64) for w1 (w2).

Ground-state distortions

The behavior discussed so-far dealt with properties of the continuum. We did not include information about the atomic system itself. This dependence is contained in \({I}_{{l}_{k},{l}_{0}}^{({n}_{A})}({k}_{n},{k}_{A})\), given by Eq. (46), with interaction described by \({J}_{{n}_{A}}({k}_{A}{r}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}})\). In the weak-field limit one has kA → 0, but a characteristic length scale for ri is required to further understand this contribution. Positions of relevance correspond to regions of non-zero ground-state density. At large distances (ri → ∞) the ground state is proportional to \({e}^{-{r}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}/{a}_{0}}\) where the characteristic length scale a0 is the effective Bohr radius determined from \({I}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\equiv {\hslash }^{2}/2{m}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}{a}_{0}^{2}\). This means that position coordinates ri (ionization locations) are dominated by contributions satisfying

which we have written in terms of both a bound-state intensity parameter \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}\equiv 2{U}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}/{I}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\)62 and the Keldysh parameter γ64 (kAri = ri/γa0).

In the weak-field limit \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}\ll 1\) (γ ≫ 1), Keldysh’s parameter re-scales the interaction such that the Bessel function \({J}_{{n}_{A}}({r}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}/\gamma {a}_{0})\) changes so slowly across the atomic ground-state that it may be treated as a lowest-order polynomial. This may be understood from the small-argument behavior98

For large values of \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}\,(\gamma \ll 1)\) the Bessel function oscillates rapidly over the ground-state density. A near-infinite number of polynomial terms may be required to describe emission. Ionization has a qualitatively different behavior. We did not take \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}\to 0\) as in the continuum-state contribution since this represents the lowest ATI order n = 1 alone.

The lowest-order polynomial approximation mentioned earlier has been integrated with the prior approximations for \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\to 0\). This integration results in an additional dotted curve, as depicted in Fig. 3. This model provides an accurate prediction of emission for weak fields. However, for strong field values, both the total and partial rates display significant deviations. These additional deviations mark the emergence of strong-field ground-state distortions at high intensities.

Characteristic behavior

In our earlier exploration of a Ti-sapphire laser operating at 800 nm and with an intensity of 1014 W/cm2, we identified a significant departure from the weak-field regime, evidenced by \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\approx 4\). Furthermore, when examining a hydrogen-like target, we observe \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\) surpassing \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}\), which is roughly 1. This departure from weak-field ionization primarily stems from distortions in continuum states, with ground-state distortions contributing secondarily, as indicated by the Keldysh parameter.

Expanding on this analysis, under even longer wavelength conditions, where \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\gg {{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}\gg 1\), we derive the tunneling exponent. This expression, extensively studied in works such as62,85,93,99,100, is given by:

This expression characterizes ionization by a nearly static (adiabatic) field, as elaborated in ref. 101. Importantly, tunneling phenomena arise from the influence of long wavelength fields rather than from intensity alone. It’s notable that works such as refs. 15,102 construct a similar exponent to describe static-field emission, assuming a weak electric field.

On the contrary, when examining X-ray drivers of the type under consideration, it’s notable that \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\) consistently remains below 1. This distinction is important. The intensity parameter \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\) only slightly deviates from weak-field behavior in this scenario. However, intriguingly, we find that \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}\) can be notably larger than 1, signifying the dominance of ground-state distortions. This marks a departure from the tunneling limit.

At the point of channel closure, bound-state distortion reaches its peak. For a given photon energy ℏω, this upper bound is given by:

and is depicted with \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}^{{{{\rm{(cl)}}}}}\) in Table 1 for a set of photon energies ℏω. Higher frequency fields facilitate greater bound-state distortions and stronger field effects at channel closure.

The scenarios under consideration, which are distinguished by their long and short wavelengths, display unique characteristics. Both scenarios lead to substantial distortion in the bound state (γ ≪ 1). In the case of long wavelengths, the distortion in the continuum state, (\({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\)), significantly surpasses the distortion in the ground state (\({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}\)). On the other hand, in the strong-field limit of short wavelengths, the distortion in the ground state exceeds that in the continuum. The discussion of intensity parameters within the model, particularly at long wavelengths, is elaborated in Section 3 of Chapter 5 from ref. 103. It becomes clear that relying solely on the Keldysh parameter is inadequate for fully capturing the phenomena of strong field ionization. A thorough understanding of these processes necessitates considering contributions from both the ground state and the continuum state.

In Fig. 4, we use diagrams similar to that of ref. 104 to present intensity values corresponding to fixed \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}=0.1\) (light blue lines) and \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}=0.1\) (green lines) for hydrogen, plotted against both photon energy (a) and wavelength (b). These contours delineate the laser parameters marking the onset of strong-field (non-perturbative) behavior attributed to each contribution. Additionally, we’ve included a yellow line representing a 250 eV and a red line representing an 800 nm driving field in each panel for reference. A pink curve labeled \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\le 1-{{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{0}\) represents the channel closure condition for single-photon ionization. Emission at intensities preceding this bound are within the scope of our model. Panel (a) illustrates that ground-state distortion precedes continuum-state distortions across all X-ray frequencies, with the gap widening as energy increases, owing to the scaling behaviors of \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\propto 1/{\omega }^{3}\) and \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}\propto 1/{\omega }^{2}\). In panel (b), we’ve represented wavelengths on a logarithmic scale, highlighting how this frequency scaling leads to the dominance of continuum-state distortions over bound-state distortions at longer wavelengths. The crossover point \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}={{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}\) occurs at Ip = 2ℏω (\({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{0}=2\)) and is indicated with a vertical black line.

Figure depicts two diagrams. a Represents the relationship between photon energy (ℏω) and intensity (I), and b illustrates the correlation between wavelength (λ) and intensity. The intensity values that lie above the curves, which correspond to \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}=0.1\) (light blue lines) and \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}=0.1\) (green lines), signify a deviation from the perturbative values. A curve denoted by \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\le 1-{{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{0}\) (pink lines) symbolizes the channel closure condition and the maximum intensity permissible by our model. The curve where \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{0}=2\) (vertical black lines) marks the wavelength at which \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}={{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}\). Additional curves are incorporated to underscore the characteristic behavior for a strong field at 250 eV (vertical yellow lines) and 800 nm (vertical red lines).

Further insights from this analysis are gained from Figs. 2 and 3. In each panel, vertical lines are positioned at \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}=0.1\) and \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}=0.1\). Figure 3 reveals a marked deviation from weak-field results for ground-state distortion (\({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}\, \gtrsim \, 0.1\)) in both panels (a) and (b). Moreover, in panel (c) of Fig. 2, we observe that \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1} \, \gtrsim \, 0.1\) leads to the non-perturbative formation of many ATI orders of similar magnitude in the energy distribution, which is a distinct strong-field feature.

Ionization of real atoms

The study of strong field ionization within a 3D framework reveals a complex interplay of factors that shape the ionization dynamics. Unlike standard 1D models, which do not include the centrifugal barrier, 3D models account for this crucial element, providing a more accurate representation of the atomic Hamiltonian for states with different parity105. It is within this more intricate setting that we observe the effects of strong field ionization—still present but rendered with less intensity compared to their 1D counterparts.

The findings presented here align with the model detailed in ref. 50. It’s crucial to highlight that these prior results were formulated for the broad case of elliptical polarization. A simplified derivation of these results, tailored for the case of linear polarization, is provided in the “Supplementary Note 1: Three-Dimensional Emission" section of the Supplementary Information. This format facilitates a more direct comparison with one-dimensional outcomes. Parity extends to orbital angular momentum, leading to an expanded array of ionization channels. We observe that the strong-field effects, which were somewhat overstated in the unidimensional model, are consistent in the three-dimensional scenario. The overall conclusions remain unchanged.

Above-threshold ionization

We now turn our attention to the three-dimensional version of hydrogen, aiming to demonstrate the onset of above-threshold ionization and to establish consistency with our previous one-dimensional results. The initial bound electron is associated with the 1s − state (l0 = 0, Ip ≈ 13.6 eV) of the atom, which corresponds to the potential

Upon absorption of n photons, the electron is ejected into a discrete set of energy levels \({\varepsilon }_{k}\equiv {\hslash }^{2}{k}_{n}^{2}/2{m}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}\), resulting in final states of definite parity, as in the one-dimensional case. The results of our study are depicted in Fig. 5, where we have determined the ionization rates for hydrogen atoms under the influence of fields with photon energies of ℏω = 125 eV. These fields vary in intensity from 1014 W/cm2 to the threshold of channel closure.

Panel a indicates the total ionization rate w (blue line). Panels b and c give partial rates into each ATI peak as a heat map, where b is on a log scale and c is on a linear scale. An additional dashed black line indicates w ∝ I scaling in a and εk ∝ Up scaling in b. Vertical lines are included for intensity parameters at \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}=0.1\) (light blue) and \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}=0.1\) (green). The vertical pink line labeled T1/2 = 50 as corresponds to a limit where 50% of the ground-state is depleted after 50 as. Panels d and e present the results of b and c alternatively. Panel e is a zoomed-in version of panel d. A black dashed line shows the ∝ I scaling of the first peak (1) with respect to intensity. Higher-order peaks are indicated by a line labeled (2) for the second-order peak, with subsequent higher-order peaks represented by thinner lines continuing sequentially to the right of (2) without labels. Panels d and e contains a vertical gray dot-dashed line at I ≈ 7 × 1018 W/cm2 corresponding to the maxima for the n = 1 emission peak. ATI emission energy vs rate have been plotted in panel f for intensities at this maxima as blue bars and a location very close to the threshold as red bars (1.1 × 1019 W/cm2) to show suppression of n = 1 near threshold.

Figure 5 comprises panels (a), (b), and (c), reflecting the findings parallel to those in Fig. 2. Panel (a) illustrates the aggregate ionization rate (blue line), which generally conforms to the anticipated w ∝ I trend (dashed black line) for field intensities up to roughly \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}=0.1\) (indicated by the green line). Notably, there is a slight divergence from the w ∝ I relation due to the influence of ground state distortion (small γ). This divergence intensifies around \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}=0.1\) (light blue line), signifying a disruption in the continuum. A supplementary pink line denotes an intensity level at which 50% of the ground-state population undergoes ionization within 50 as.

The presence of strong-field effects is apparent; however, their significance is reduced when transitioning from one to three dimensions. Ground state distortion, characterized by \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1} \, \gtrsim \, 0.1\), has a small effect on the ionization rate until the emergence of continuum-state distortions, denoted by \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}} \, \gtrsim \, 0.1\). The behavior of free electrons remains consistent across different dimensions, with acceleration aligned with the field polarization. The interaction between the initial ground state and the applied field dictates the velocity at which particles transition into the continuum upon ionization. It is important to note that the characteristics of bound states are strongly influenced by dimensionality.

Panels (b) and (c) present the energy \({\varepsilon }_{k}={\hslash }^{2}{k}_{n}^{2}/2{m}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}\) of ATI peaks plotted against the field intensity I. Panel (b), displayed on a logarithmic scale, uncovers a series of ATI peaks whose cutoff energy scales ∝ Up (represented by the black dashed line), indicative of non-perturbative phenomena. Conversely, panel (c) demonstrates the emission of ATI orders significantly less energetic than in the one-dimensional scenario. The processes with n = 1, 2, and 3 generate a comparable quantity of electrons, albeit only near the threshold.

Panels (d) and (e) present a unique interpretation of the data from panels (b) and (c) where (e) is a zoomed in version of (d). They plot the partial-rates associated with ATI channels, denoted as n, against the intensity (blue lines). The labels 1 and 2 are included to indicate the first two orders. For orders 3 and above, they are not explicitly labeled but can be identified as the thinner curves that sequentially follow the curve for n = 2 from left to right. In this scenario, the single-photon process for n = 1 peaks at approximately 7 × 1018 W/cm2, predominating across most intensities until it is surpassed by the n = 2 process just before the channel closure. The peaks for subsequent higher-order emissions mostly conform to the weak-field perturbative scaling.

Lastly, panel (f) delineates the partial rates for various ATI peaks at two distinct intensities. The initial intensity, approximately 7 × 1018 W/cm2, highlights the peak of single-photon emission rates (blue bars), while the latter, just before channel closure at roughly 1.1 × 1019 W/cm2, illustrates a scenario where two-photon (n = 2) processes are dominant in electron production compared to single-photon emission (red bars). An escalation in field intensity, represented by a larger Reiss parameter \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\), propels the lowest-order n = 1 ATI peak nearer to the ionization threshold. As suggested by the transition matrix element between atom-Volkov states in ref. 51, this shift augments the probability of higher-order continuum-continuum transitions (radiative scattering). This intriguing effect merits in-depth investigation in subsequent studies.

Poly-electronic systems

Our results are potentially applicable to targets with multiple electrons, assuming a sequential ionization mechanism is valid106,107,108,109,110. In this scenario, individual active electrons are removed one by one, and rate equations are applied. Correlated emission is not included in this approximation, which is expected to be valid if the pulses are “long enough" and electrons can be removed from each residual ion by a single photon20. In the weak-field perturbative work of ref. 20, a sequential ionization model is justified for helium applications involving photons with single quanta energetic enough to overcome the single-electron ionization potential of both the neutral atom and single ion. If the photons are energetic enough to overcome the neutral potential but not the ionic potential, a non-sequential mechanism becomes relevant. A clear intermediate ionic state is not formed, and emission becomes correlated. This limit is akin to the closure of the single-photon ionization channel for the ion. Although ref. 20 does not discuss strong fields, we anticipate a similar mechanism here, where the energy of quanta must now be compared to the field-shifted ionization potential \({\tilde{I}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}\) used in our work.

We expect correlated emission in the non-sequential regime, where electrons, treated as single-particle functions, scatter off each other in a manner that is conceptually akin to the non-sequential mechanisms discussed in refs. 58,111,112. We may also observe additional scattering of electrons off residual ionic cores, reminiscent of the re-scattering events that emerge beyond the closure of the single-photon ionization channel, as seen in the ionization of hydrogen in Fig. 3(h, i) of ref. 10. This stands in contrast to the lack of re-scattered electrons observed in Fig. 3(g) of the same reference. In the case of helium, the non-sequential criteria \(\hslash \omega \, < \, {\tilde{I}}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{({{{{\rm{He}}}}}^{+})}\) aligns precisely with the channel closure condition of the ion’s single-photon emission process. Here, electrons scatter off both ionic cores and each other. Our current model describes the emission of direct electrons using only the lowest-order term of the systematic expansion.

We anticipate that incorporating higher-order scattering diagrams, similar to those in refs. 51,52,53,58,111,112, into the model could extend its applicability to non-sequential emission processes involving few-electron atoms. We also anticipate that the model could be applicable to molecular systems within the Born-Oppenheimer approximation under analogous sequential conditions. The initial-bound ϕ0(r) and final-continuum \({{{{\mathbf{\phi }}}}}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(-)}({{{\bf{r}}}})\) states of the electronic Hamiltonian are represented as a linear combination of partial waves. The steps implemented in our model would proceed identically with these substituted states of the molecule.

Conclusion

We investigated the onset of strong-field ionization of atoms in relation to X-ray driving fields. Our study revealed substantial strong-field effects, culminating in the emergence of higher-order perturbative and non-perturbative emission peaks. Ionization rates deviated significantly from the ∝ I scaling expected in the lowest-order perturbative limit. The Keldysh parameter \(\gamma =\sqrt{{I}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}/2{U}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}}\) (with \({{{{\mathcal{Z}}}}}_{1}=1/{\gamma }^{2}\)) and the Reiss parameter \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}={U}_{{{{\rm{p}}}}}/\hslash \omega\) served as effective metrics in distinguishing the transition from strong to weak field ionization.

At first glance, it may seem that the impact of strong-field effects is less pronounced in three dimensions compared to their one-dimensional counterparts. However, this may not be an accurate interpretation. The lines labeled as T1/2 = 50 as in various figures correspond to intensity values causing a 50% reduction in the ground-state population after 50 as, associated with some of the shortest pulses available. In the one-dimensional results, this threshold was reached prematurely at approximately 1017 W/cm2, attributed to an exaggerated n = 2 process. It’s improbable for pulses to increase swiftly enough for ejected electrons to experience higher intensities before ground-state depletion. In contrast, in the detailed 3D results, the T1/2 = 50 as mark is located just beneath the channel closure condition, where the first two ATI orders display comparable magnitudes. Furthermore, if pulse envelopes escalate rapidly enough the rates will actually decline due to channel closure and stabilization effects. In such a situation, continuum state distortions \({{{\mathcal{Z}}}}\) might exceed unity, and γ could be further diminished, enabling the observation of more pronounced strong-field effects accompanied by a decrease in ground-state depletion.

With the advent of high intensity X-ray pulses produced by XFELs, it is now possible to experimentally explore the regime treated in this paper. Therefore, the aim of this work is to use analytic results to both gain insight into this interesting limit of ionization and help experimentalists plan fruitful experiments using attosecond XFEL sources, such as the ones very recently demonstrated at LCLS113.

The ideal amalgamation of atomic target and laser interaction to maximize the intensity of strong-field effects remains elusive. Nevertheless, additional theoretical and experimental explorations in this direction could yield a more profound understanding of strong-field ionization in an asymptotic limit that is seldom considered. If a notable deviation from perturbative behavior in electron emission is observed, it would be logical to expect analogous non-perturbative behavior in the generation of radiation. As such, the prospect of high-order harmonic generation warrants further contemplation.

Data availability

Simulation data can be provided upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Programs used to produce data can be provided upon reasonable request.

References

Young, L. et al. Femtosecond electronic response of atoms to ultra-intense X-rays. Nature 466, 56–61 (2010).

Doumy, G. et al. Nonlinear atomic response to intense ultrashort X-rays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 083002 (2011).

Fuchs, M. et al. Anomalous nonlinear X-ray Compton scattering. Nature Phys. 11, 964–970 (2015).

Duris, J. et al. Tunable isolated attosecond X-ray pulses with gigawatt peak power from a free-electron laser. Nature Photon 14, 30–36 (2020).

Montironi, M. et al. Xleap-ii motion control. In 17th Int. Conf. on Acc. and Large Exp. Physics Control Systems ICALEPCS2019 (JACoW Publishing, 2019). https://doi.org/10.18429/JACoW-ICALEPCS2019-WEPHA099.

Agostini, P., Fabre, F., Mainfray, G., Petite, G. & Rahman, N. K. Free-free transitions following six-photon ionization of xenon atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 42, 1127–1130 (1979).

Bachau, H., Budriga, O., Dondera, M. & Florescu, V. Above-threshold ionization of hydrogen and hydrogen-like ions by X-ray pulses. Open Physics 11, 1091–1098 (2013).

Tilley, M., Karamatskou, A. & Santra, R. Wave-packet propagation based calculation of above-threshold ionization in the X-ray regime. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 48, 124001 (2015).

Varma, H. R., Ciappina, M. F., Rohringer, N. & Santra, R. Above-threshold ionization in the X-ray regime. Phys. Rev. A 80, 053424 (2009).

Zhou, Z. & Chu, S.-I. Multiphoton above-threshold ionization in superintense free-electron X-ray laser fields: Beyond the dipole approximation. Phys. Rev. A 87, 023407 (2013).

Ivanov, I. Spin-flip processes and nondipole effects in above-threshold ionization of hydrogen in ultrastrong laser fields. Phys. Rev. A 96, 013419 (2017).

Tumakov, D. A., Telnov, D. A., Plunien, G., Zaytsev, V. A. & Shabaev, V. M. Relativistic mask method for electron momentum distributions after ionization of hydrogen-like ions in strong laser fields. Eur. Phys. J. D 74, 1–8 (2020).

Dondera, M. & Bachau, H. Exploring above-threshold ionization of hydrogen in an intense X-ray laser field through nonperturbative calculations. Phys. Rev. A 85, 013423 (2012).

Bethe, H. & Salpeter, E.Quantum Mechanics of One-and Two-electron Atoms (Springer, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-12869-5.

Landau, L. & Lifshitz, E.Quantum Mechanics: Non-Relativistic Theory vol. 3 (Elsevier, 1981). [Nauka, 1974].

Perelomov, A., Popov, V. & Terent’Ev, M. Ionization of atoms in an alternating electric field. Sov. Phys. JETP 23, 924–934 (1966).

Bucksbaum, P. H., Freeman, R. R., Bashkansky, M. & McIlrath, T. J. Role of the ponderomotive potential in above-threshold ionization. JOSA B 4, 760–764 (1987).

Eberly, J. H., Javanainen, J. & Rzażewski, K. Above-threshold ionization. Phys. Rep. 204, 331–383 (1991).

Fedorov, M. V. Atomic and free electrons in a strong light field (World Scientific, 1997). https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812817204.