Abstract

Turbulence in active fluids is a rapidly developing area in active-matter research. Yet the mechanisms and universal statistics of turbulence in a binary mixture of counter-rotating spinners remain unclear. We uncover activity-driven crossover from phase separation to a turbulent state in a two-dimensional system of counter-rotating spinners. This state exhibits spatiotemporal chaos with fluctuating vortex doublets that form, decay, and reappear. We study the statistical properties of this turbulence, using the active-rotor Cahn-Hilliard-Navier-Stokes model, and show that, as the activity increases, the vorticity ω ∝ ϕ, the scalar field that distinguishes regions with clockwise- and counter-clockwise rotation. Using direct numerical simulations, we characterize the power-law forms of fluid-energy spectra and show they are significantly different from those in fluid and bacterial turbulence. In addition to presenting evidence for small-scale intermittency in active-rotor turbulence, we characterize flow-topology statistics and contrast it with that in 2D fluid turbulence. Subsequently, we propose experimental tests for our predictions, and suggest biological implications of active-rotor turbulence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Turbulence abounds in nature: it manifests itself from astrophysical to biophysical scales and continues to pose challenging problems for physicists, mathematicians, biologists, and engineers. Over the last decade or so, turbulence in active fluids, driven via internal active mechanisms and not by external energy input, has attracted a lot of attention [see, e.g., refs. 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Such active fluids belong to the class of nonequilibrium active-matter systems16,17 that include the collective motion of self-propelled particles18, liquid phases without attractive forces19, and dense bacterial suspensions and their non-living equivalents20,21,22,23, to name but a few. There is increasing interest in active-fluid systems with self-rotating particles24,25,26,27,28,29,30, which have been shown to display a distinct type of torque-induced phase separation31,32. In particular, mixtures of counter-rotating particles exhibit phase separation in both wet33 and dry34 environments. Studies of self-rotating particles have important biological implications, for they are found in a variety of biological systems, e.g., spinning organisms like sperm-cell clusters34, the bacterium Thiovulum majus35, dancing Volvox algae36, and starfish embryos37; synthetic experimental systems have also been developed38,39,40.

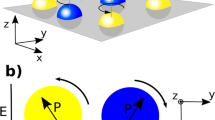

We consider a system of counter-rotating active spinners Fig. 1a that exhibits coarsening41, into phases with clockwise- and anticlockwise-rotating spinners. We demonstrate that, as we increase the activity, this system crosses over to a hitherto unanticipated nonequilibrium statistically state (NESS) of emergent active-rotor turbulence, which leads, in turn, to coarsening arrest. We examine the statistical properties of active-rotor turbulence, both theoretically and numerically, and show that it is markedly different from two-dimensional (2D) fluid turbulence42,43 and active-fluid turbulence in a variety of systems [see, e.g., refs. 1,2,7,8,10,11,12,13,15]. We discuss the possible implications of our work for biological and synthetic systems with active spinners36,38,39,40,44.

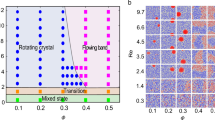

a A schematic diagram showing CCW (red) and CW (blue) phases separated by an interfacial region (orange) of width ϵ; b an illustrative pseudocolor plot of ω in the active-rotor-induced turbulent NESS with vortex doublets [shown enlarged in (c)]; pseudocolor plots of ω for d τ = 0.5, e τ = 1.5, f τ = 4, and g τ = 5, with corresponding pseudocolor plots for ϕ in (h–k), respectively, at representative times, showing partial phase separation at low values of τ and turbulent NESSs, with ω ∝ ϕ, at large values of τ. As τ increases, the number of vortex doublets rises, but their sizes decrease. For the full spatiotemporal evolution of these fields, see Supplementary Movies 1–4.

Our study is based on an extensive analysis of the 2D minimal hydrodynamical description of the active-rotor system [see ref. 41 for the relation with rotor-particle-based models] that uses the following partial differential equations (PDEs) [henceforth, the active-rotor Cahn–Hilliard–Navier–Stokes (ARCHNS) model] in 2D in terms of the vorticity ω [for the velocity formulation of Eq. (3) see the Supplementary Methods]:

the scalar order parameter ϕ, which distinguishes between regions with rotors that rotate counterclockwise (CCW with ϕ > 0) and clockwise (CW with ϕ < 0), is coupled to the fluid velocity u as in the incompressible Cahn–Hilliard–Navier–Stokes PDEs [τ = 0 in Eq. (3)] for a binary-fluid mixture12,45,46 with the free-energy functional \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\), the constant fluid density ρ = 1, and M, ϵ, σ, ν, and β the mobility, interfacial width, surface tension, kinematic viscosity, and friction coefficient, respectively. The strength of the activity depends on the magnitude of the torque \(\tau =\tau {\hat{e}}_{z}\), which is perpendicular to the xy plane, like the vorticity \(\omega =\omega {\hat{e}}_{z}\) that is related to the stream function ψ via the Poisson equation (4). For details, see the Section on “Methods” and the Supplementary Methods. At low values of τ, this model leads to phase separation into clockwise- and anticlockwise-rotating states; however, as we increase τ, this phase separation is suppressed by the emergent active-rotor turbulence, in a manner that is qualitatively similar to the suppression of phase separation by conventional fluid turbulence46,47. We uncover several properties of active-rotor turbulence. It displays vortex doublets Fig. 1b, c, which also appear in the absence of turbulence41. Next, the scalar order parameter ϕ, which distinguishes between regions with clockwise- and anticlockwise-rotating states, turns out to be proportional to the vorticity ω Fig. 1d–k, a remarkable proportionality that has not been seen in any binary-fluid system so far; we explain this theoretically via a dominant-balance argument. With increasing τ, active-rotor-turbulence leads to fluctuations in the energy, a suppression of phase separation, and an increase in the Reynolds number [Fig. 2]. Energy and concentration spectra [Fig. 3] show well-developed power-law ranges, with τ-independent universal exponents for 1.5 ≲ τ; these exponents are markedly different from their counterparts in 2D fluid turbulence42,43 and bacterial turbulence8,10,11,15. Not only does active-rotor turbulence display power-law spectra, but it also shows manifestations of small-scale intermittency, which we uncover by examining the length-scale dependence of the probability distribution functions (PDFs) of velocity-increment and their flatness Fig. 4a, b. We compute the Okubo-Weiss parameter Λ, which can be used to distinguish between vortical and extensional regions of the flow, and show that its PDF Fig. 4c is qualitatively akin to its counterpart in 2D fluid turbulence. We suggest that active-rotor turbulence has possibly important biological implications; and we make specific proposals for experimental studies of active-rotor turbulence in both biological34,35,36,37 and synthetic systems38,39,40.

Plots versus the scaled time tΩL of a the scaled energy E(t)/E0, where \({E}_{0}=E(t={\Omega }_{L}^{-1})\), and b the coarsening-arrest length scale Lϕ(t), for τ = 0.5, 1, 1.5, 4, and 5. c Plots versus τ of the mean domain size 〈Lϕ〉 (red curve) and the integral-scale Reynolds number Re (blue curve).

Log–log plots of compensated spectra versus the scaled wavenumber 〈Lϕ〉k, for τ = 1, 3, 4, and 5, with power-law scaling regions shaded in gray: a k−1E(k) [scaling region 1 ≲ k ≲ 8]; b k5E(k) [scaling region 8 ≲ k ≲ 35]. c k−3S(k) [scaling region 1 ≲ k ≲ 8]; d k3S(k) [scaling region 8 ≲ k ≲ 35]; for the spatiotemporal evolution of these pseudocolor plots, see Supplementary Movies 1–4. Log-lin plots of Tu(k)(red), Trot(k)(green), Sϕ(k)(orange), 2νk2E(k)(blue) and 2βE(k)(magenta) [see Eq. (11)] versus 〈Lϕ〉k, in the NESS, for β = 0.3 and e τ = 1 and (f) τ = 5. For plots of the energy and rotational fluxes, Πu(k) and Πrot(k), see Fig. S1a–c in the Supplementary Figs.g Scatter plots of ω versus ϕ for different values of τ illustrating ω ∝ ϕ; h the dashed lines show linear fits, which have slopes m(τ) that are plotted versus τ.

Semi-log plots of: a the PDFs of the longitudinal-velocity increments δu(l) for τ = 1 and separations l = 30δl, l = 50δl, l = 100δl, and l = 200δl; these PDFs are nearly Gaussian, unlike those for τ = 5; b the PDFs of longitudinal-velocity increments δu(l) for separations l = 30δl, l = 50δl, l = 100δl, and l = 200δl for τ = 5; c the flatness \({F}_{4}\equiv {S}_{4}/{({S}_{2})}^{2}\) versus l, for τ = 1, 3, 4, and 5, shows distinct deviations from the Gaussian value of 3 for τ > 1 and small length scales l.

Results

We carry out a series of direct numerical simulations (DNSs) that we have designed to illustrate the emergence of active-rotor turbulence, as we increase τ in the ARCHNS model (1–4). In Fig. 1b, we present a pseudocolor plot of ω at a representative time in the turbulent NESS, that contains several vortex doublets [one is enlarged in Fig. 1c]. Figure 1e–h show how such pseudocolor plots of ω evolve as we increase τ from 0.5, 1.5, 4, up until 5; Fig. 1h–k are, respectively, the counterparts of these plots for ϕ. The spatiotemporal evolution of these plots is given in the Supplementary Movies 1–4. These videos show clearly that, with increasing τ, our system of counterrorating spinners goes into a nonequilibrium, but statistically steady, state that displays spatiotemporal chaos and in which vortex doublets are created and destroyed as they are advected by the emergent active-rotor turbulence.

From Fig. 1e, i we observe that phase separation occurs at τ = 0.5, but it is arrested to some extent. The plots versus tΩL of E(t)/E(t = 1/ΩL) and Lϕ(t) in Fig. 2a, b, respectively, show that the fluctuations in the energy increase with τ, whereas the coarsening-arrest length decreases. We quantify coarsening arrest by the plots in Fig. 2c, which show that the mean domain size 〈Lϕ〉 (red curve) decreases with τ as the integral-scale Reynolds number Re (blue curve) increases.

The pseudocolor plots in the second and third rows of Fig. 1 uncover a remarkable crossover that occurs at τ ≃ 1.5 from a NESS with partial phase separation to another NESS in which active-rotor-induced turbulence (i) suppresses phase separation and (ii) the field ω ∝ ϕ. This suppression of phase separation, or coarsening arrest, is similar to its counterpart in binary-fluid turbulence46,48. The proportionality of ω and ϕ has not been seen in any other binary-fluid model. We develop a theory of this proportionality below.

Two important lengths, L and Lϕ, characterize our system. They are, respectively, the integral and coarsening-arrest lengths scales, which are defined in terms of the energy spectrum E(k) and phase-field spectrum S(k) as follows:

the tildes denote spatial Fourier transforms, k and \({k}^{\prime}\) are the moduli of the wave vectors k and \({{{\bf{k}}}}^{\prime}\), and < ⋅ >t denotes the time average over the statistically steady state. In the absence of turbulence, Lϕ grows with time because the small- and large-ϕ regions undergo phase separation; however, as the activity increases, active-rotor-induced turbulence arrests this phase separation, Lϕ saturates at a finite value Fig. 2b, which is the coarsening-arrest length scale [cf. ref. 46 for the suppression of phase separation by conventional fluid turbulence in a binary-fluid mixture]. In our model, not only does Lϕ denote the coarsening-arrest length scale, but it also yields an estimate for the typical vortex size, at large activity τ, because ω ∝ ϕ here [see Fig. 1f, j, g, k]. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 2c, 〈Lϕ〉 decreases with increasing activity (τ), indicating that the higher the activity τ, the smaller the vortical structures [cf. ref. 49 for active nematics].

We compute the energy spectrum E(k) and the phase-field spectrum S(k) for various values of the activity τ; we plot these in Fig. 3a–d. One way of uncovering a power-law scaling range, say E(k) ~ k−n, is to make a log-log plot of the compensated spectrum knE(k) versus k. This log-log plot shows a flat region (indicated by dashed horizontal lines) over the range of wavenumbers k in which such a scaling range occurs; to the right and left of this scaling range, the compensated spectrum falls, because, at small k, there is another power-law form [see Fig. 3a, c] and, at large k, viscous dissipation leads to rapid decay, which is predominantly exponential. In Fig. 3, we present log–log plots of compensated energy and phase-field spectra versus the scaled wavenumber 〈Lϕ〉k for τ =1, 3, 4, and 5. The plots in Fig. 3a–d, which display k−1E(k), k5E(k), k−3S(k), and k3S(k), respectively, are consistent with the following scaling forms at small and intermediate values of k [see the dashed horizontal lines in Fig. 3a–d]: (i) E(k) ~ k and S(k) ~ k3, for 1 ≲ 〈Lϕ〉k ≲ 8 [especially for τ = 1]; and (ii) E(k) ~ k−5 and S(k) ~ k−3, for 11 ≲ 〈Lϕ〉k ≲ 35 [especially for τ > 1]. If we assume ω ∝ ϕ, then the spectrum of ϕ is proportional to the enstrophy spectrum, i.e., \(S(k) \sim \Omega (k) \sim | \tilde{\omega }({{{\bf{k}}}}){| }^{2} \sim {k}^{2}E(k)\), which is consistent with Fig. 3. The power laws we obtain numerically in these spectra are unique to this system, differing significantly from those in conventional and active-fluid turbulence. We note that these power laws are universal, at large τ, in the sense that, given the resolution of our DNSs, their power-law exponents do not depend on τ. An analytical theory for these exponents remains an important challenge.

At low-Re, one might argue, naïvely, that ω ∝ ϕ because, if some particles spin clockwise and others counterclockwise, the vorticity that they impart to the fluid should be determined by the net number of counterclockwise spinners. However, we note that (a) we consider the case with an equal concentration of CW and CCW spinners and (b) our DNS shows that ω ∝ ϕ holds well only for large τ, when the system displays turbulence and linear theory is not valid. This proportionality can be explained only if we look at the spectral balance carefully, so our result ω ∝ ϕ is both surprising and important; we show this below.

In Fig. 3e, f we present, for τ = 1 and τ = 5, respectively, log-lin plots of the terms in Eq. (11), namely, Tu(k) (red), Trot(k) (green), Sϕ(k) (orange), 2νk2E(k) (blue), and 2βE(k) (magenta) versus 〈Lϕ〉k, for the illustrative value β = 0.3.

These plots show that, for low activity [Fig. 3e], the four terms Tu(k), T rot(k), Sϕ(k), and 2νk2E(k) play dominant roles in the spectral balance (11); all these terms have significant weight over all wavenumbers k and display only mild peaks and/or troughs. As we have seen in Fig. 1, phase separation is partially arrested in this regime; there are no prominent vortex doublets, and ω is not quite proportional to ϕ. The plot of Πu(k) [Fig. F1a in the Supplementary Figs.], the advection flux (12), shows that the system has a split cascade [see Section 3.3 on split energy cascade in ref. 50], at τ = 1, that crosses over from an inverse to a forward cascade of energy when 〈Lϕ〉k ≃ 8, because of the arrested phase separation.

By contrast, for high activity [say τ = 5 as in Fig. 3f], the dominant terms in the spectral balance (11) are the rotation-injection term Trot(k) and the viscous-dissipation and frictional contributions −2νk2E(k), and −2βE(k) which balance each other, more-or-less locally in k [the term Tu(k) contributes marginally at small values of k], so the transfer across scales is reduced; in particular, the advection flux (12) shows that the system has an inverse-cascade of energy when 〈Lϕ〉k ≲ 8 and hardly any cascade thereafter, for τ ≥ 3 [see Fig. F1a in the Supplementary Figs.]. The torque-driven motion dominates over forces that would normally lead to coarsening. Finally, a dominant-balance argument [see the Supplementary Methods] yields the theoretical prediction

this is consistent with our qualitative suggestion ω ∝ ϕ in the large-τ plots of Fig. 1. We verify the relation (8) explicitly by making scatter plots of ω versus ϕ for different values of τ in Fig. 3g; the dashed lines show linear fits, which have slopes m(τ) that are plotted versus τ in Fig. 3h.

Since the pioneering work of Frisch and Parisi51,52 on intermittency corrections to simple Kolmogorov-type scaling52,53,54 in three dimensions, which yields, inter alia, a power-law fluid-energy spectrum E(k) ~ k−5/3, for the inertial range that lies between the energy-injection and dissipation scales52, the study of such corrections has played a central role in the characterization of fluid turbulence. Given that the energy spectra in Fig. 3 exhibit power-law scaling ranges that are qualitatively reminiscent of turbulence in 2D fluids42,43,55 and active fluids2,8,10,11, it is natural to ask whether active-rotor turbulence also exhibits intermittency and flow topologies of the types seen in classical-fluid42,43,55 and active-fluid8,10,11,15 turbulence. To answer this question, we calculate several PDFs. The PDFs of the Cartesian components of u are nearly Gaussian, like their fluid and active-turbulence counterparts [see, e.g., refs. 56,57,58]. To uncover intermittency52, we first define the longitudinal velocity increments \(\delta {{{\boldsymbol{u}}}}(l)\equiv \left({{{\boldsymbol{u}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{x}}}}+{{{\boldsymbol{l}}}})-{{{\boldsymbol{u}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{x}}}})\right)\cdot \hat{{{{\boldsymbol{l}}}}}\) and then obtain their PDFs, for different values of the separation l = ∣l∣, which we display in Fig. 4b for τ = 5 [for τ = 1, see Fig. 4a]; these PDFs show distinct scale dependence, more so for τ = 5 than for τ = 1, because there is more rotor-induced turbulence in the former case. To quantify this scale dependence, we compute the order-p longitudinal-velocity structure functions Sp(l) ≡ 〈[δu(l)]p〉 and, therefrom, the flatness \({F}_{4}(l)\equiv {S}_{4}(l)/{[{S}_{2}(l)]}^{2}\), which increases as l decreases [see Fig. 4c], a clear signature of small-scale intermittency; the value of F4(l) increases as τ goes up from 1 to 5; and at large l it is close to 3, the value of the flatness for a Gaussian PDF, especially for τ = 1.

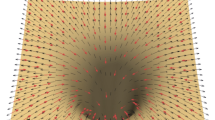

To investigate the topology of active-rotor flow, we calculate Λ, the Okubo-Weiss42,55,59,60 parameter (10), and plot the PDFs \({{{\mathcal{P}}}}(\Lambda )\) in Fig. 5a for τ = 1, 3, 4, and 5; it has zero mean, by definition, and, in the NESS of rotor-induced turbulence [τ > 1], it shows a characteristic cusp at Λ = 0. We note that \({{{\mathcal{P}}}}(\Lambda )\) is skewed like its counterparts in 2D fluid turbulence42,55 and in the 2D Toner–Tu–Swift–Hohenberg model for bacterial turbulence10,11. The skewness of \({{{\mathcal{P}}}}(\Lambda )\) increases markedly as τ goes from 1 to 5 [see Fig. F1d in the Supplementary Figs.], which implies that vortical regions dominate extensional regions as τ increases [this is in consonance with the increase in ω with τ as in Fig. 1e–g]. In Fig. 5b–d, we show pseudocolor plots of the Okubo-Weiss parameter for τ = 3, 4, and 5, respectively. These plots have overlaid contours of ω = −0.6 (dashed-brown contours), ω = 0 (white contours), and ω = 0.6 (black contours); and they show clearly how Λ partitions the flow into elliptical (Λ > 0, rotation-dominated) and hyperbolic (Λ < 0, strain-dominated) regions. The white ω = 0 contours highlight the boundaries between CCW (red) and CW (blue) rotating domains. The flow topology is reminiscent of its counterpart in 2D fluid turbulence55,61.

a the PDF of the Okubo-Weiss parameter Λ [see text] for τ = 1, 3, 4, and 5. Pseudocolor plots of the normalized Okubo-Weiss paramemter Λ/Λmax for b τ = 3, c τ = 4, and d τ = 5, with overlaid contours of the normalized ω/ωmax = −0.6 (dashed-brown contours), ω/ωmax = 0 (white contours), and ω/ωmax = 0.6 (black contours).

Discussion

We have carried out the first study of active-rotor-induced turbulence in a system of counter-rotating spinners. Using the ARCHNS model (1–4), we have demonstrated that, as we increase the activity τ, phase separation into clockwise- and anticlockwise-rotating states is suppressed as active-rotor turbulence emerges. This turbulence has several properties: It displays vortex doublets, which also appear in the absence of turbulence41; next, ω ∝ ϕ, a remarkable proportionality that has not been seen in any binary-fluid system so far; energy and concentration spectra show well-developed power-law ranges, with τ-independent exponents for 1.5 ≲ τ.

Our work has uncovered statistically homogeneous and isotropic turbulence in a system of active spinners that is distinctly different from that in earlier numerical studies62,63, which have seen some signatures of low-Reynolds-number turbulence; but it is not fully developed like the turbulence we find. Reference 62 sees the emergence of turbulent-like motion, but this gives way to a chirality-breaking transition, and the system moves to a state with a single sense of rotation. The turbulent state in ref. 63 is a transient that yields to a coherent flow with macroscopically phase-separated domains. Furthermore, refs. 62,63 do not find the vortex doublets that we obtain. It will be interesting to examine experiments with active rotors—either natural or artificial—to see whether they can attain the types of nonequilibrium states that we find and those discussed in refs. 62,63.

Although there have been experimental studies of active-rotor systems in both biological34,35,36,37 and synthetic settings38,39,40, none of them have attempted to explore high-activity regimes at which active-spinner turbulence should be found. Especially in assemblies of magnetically driven counter-rotating disks27 it should be possible to reach such a turbulent state, whose statistical properties can then be characterized by the statistical measures that we have employed. Other synthetic systems include those driven by chemical reactions64, external magnetic fields27,65,66,67, electric fields68, optical fields69, oscillating platforms70, ultrasound71, and airflow72. Rotors play important roles in diverse biological systems, too, including uniflagellar mutants of Chlamydomonas73,74, in suspensions of the bacterium Thiovulum majus, sperm-cell clusters34, and starfish embryos37. It will be interesting to explore if these systems can exhibit the type of rotor turbulence we have discussed.

What could be the biological implications or benefits of such active-rotor turbulence? Specific answers to these questions can only emerge from future studies. We note, however, that ref. 36 has already conjectured that, “…flows driving Volvox clustering at surfaces enhance the probability of fertilization during the sexual phase of their life cycle”.

Our work lays the foundation for further studies—theoretical, numerical, and experimental—of exotic turbulent states in spinner systems that can be described, e.g., by the ARCHNS model (1–4). In particular, as we will show elsewhere, this model can also exhibit states with vortex triplets; such triplets have been obtained in the single-phase study of ref. 75.

Methods

The minimal hydrodynamical description of the active-rotor system41 uses the following PDEs ARCHNS PDEs (1–4). The scalar order parameter ϕ, which distinguishes between regions with rotors that rotate counterclockwise (CCW with ϕ > 0) and clockwise (CW with ϕ < 0), is coupled to the fluid velocity u as in the incompressible Cahn–Hilliard–Navier–Stokes PDEs [τ = 0 in Eq. (3)] for a binary-fluid mixture12,45,46 with the free-energy functional \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\), the constant fluid density ρ = 1, and M, ϵ, σ, ν, and β the mobility, interfacial width, surface tension, kinematic viscosity, and friction coefficient, respectively. The strength of the activity depends on the magnitude of the torque \(\tau =\tau {\hat{e}}_{z}\), which is perpendicular to the xy plane, like the vorticity \(\omega =\omega {\hat{e}}_{z}\) that is related to the stream function ψ via the Poisson Eq. (4).

We consider a symmetric mixture of two incompressible, Newtonian liquids, and, for simplicity, the case in which the two liquids have equal viscosities. In equilibrium, these two fluids coexist, and they are separated by an interfacial region [see, e.g., refs. 47,76 for recent reviews]. The two coexisting phases of such a binary mixture are distinguished by a scalar order-parameter field ϕ(x, t), well-known in statistical mechanics47,76,77, that is related to the local composition as follows:

where ρCW and ρCCW denote, respectively, the local number of CW and CCW spinners per unit area, and the angular brackets denote a mesoscopic average76 that yields a smooth field ϕ. We consider a symmetric mixture of two incompressible, Newtonian liquids; for simplicity, we consider the case of equal viscosities. The CCW-rich (ϕ > 0) and CW-rich (ϕ < 0) phases are separated by an interface. The coupling to the Navier-Stokes equation is well known in the binary-fluid literature; we refer the reader to ref. 47 for a recent review. The active rotation, for the spinner fluids we consider, is characterized by an applied torque density τϕ, which is proportional to the order parameter ϕ and to a constant vector τ that characterizes the magnitude and direction of the rotation. The relation between our continuum model and a particle-based model for rotors is discussed in detail in ref. 41.

For the initial condition, we use a statistically homogeneous state with ϕ(x, y, t = 0) independent and identically distributed random numbers drawn uniformly from the interval [ −0.1, 0.1]; we set the vorticity ω(x, y, t = 0) to zero. The statistical properties of the nonequilibrium, statistically steady state (NESS) of active-rotor turbulence depend on the Reynolds number Re ≡ Lurms/ν, the Cahn number Cn ≡ ϵ/L, the Weber number \(We\equiv L{u}_{rms}^{2}/\sigma\), the Péclet number Pe ≡ Lurmsϵ/Mσ, and the non-dimensionalised activity \(\alpha =\tau /{u}_{rms}^{2}\) and friction \(\beta {\prime} =\beta L/{u}_{rms}\), where urms is the root-mean-square velocity, and L and Lϕ are, respectively, the integral and coarsening-arrest lengths scales, which are defined in terms of the energy spectrum E(k) and phase-field spectrum S(k) [see the Supplementary Methods] as follows: here, k denotes the wave number. We use the integral-scale frequency ΩL ≡ urms/L to non-dimensionalize time. We monitor the flow topology via the Okubo-Weiss parameter42,55,59,60

where Σ is the symmetric part of the velocity derivative tensor; Λ > 0 (Λ < 0) in the vortical (extensional) regions of the flow. The spectral energy balance is given by12,43,78

where the Tu(k, t), Trot(k, t), Sϕ(k, t), 2νk2E(k, t), and 2βE(k, t) are the k-shell averaged contributions from the advective, torque, stress-tensor (∇2ϕ ∇ ϕ), viscous dissipation, and friction, terms, respectively; their time averages in the NESS, E(k), S(k), Tu(k), Trot(k), and Sϕ(k), are defined as follows:

Here \({P}_{ij}(k)={\delta }_{ij}-\frac{{k}_{i}.{k}_{j}}{{k}^{2}}\) are the elements of the transverse projector P(k); and the fluxes because of advection and active rotation are, respectively, Πu(k) and Πrot(k). We solve the PDEs (1–4) by using pseudospectral DNSs12,79, which we describe in the Supplementary Methods.

Data availability

Simulation results are reproducible following the methodology described. The data utilized in this study can be made available from the authors upon reasonable request at nadia_bihari.padhan@tu-dresden.de.

Code availability

The code utilized in this study can be made available from the authors upon reasonable request at nadia_bihari.padhan@tu-dresden.de.

References

Wensink, H. H. et al. Meso-scale turbulence in living fluids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 14308–14313 (2012).

Bratanov, V., Jenko, F. & Frey, E. New class of turbulence in active fluids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 15048–15053 (2015).

Thampi, S. & Yeomans, J. Active turbulence in active nematics. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 225, 651–662 (2016).

Saintillan, D. Rheology of active fluids. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 50, 563–592 (2018).

Rana, N. & Perlekar, P. Coarsening in the two-dimensional incompressible toner-tu equation: signatures of turbulence. Phys. Rev. E 102, 032617 (2020).

Bowick, M. J., Fakhri, N., Marchetti, M. C. & Ramaswamy, S. Symmetry, thermodynamics, and topology in active matter. Phys. Rev. X 12, 010501 (2022).

Sanjay, C. & Joy, A. Transport phenomena in active turbulence. Pramana 96, 60 (2022).

Alert, R., Casademunt, J. & Joanny, J.-F. Active turbulence. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 13, 143–170 (2022).

Gibbon, J. D., Kiran, K. V., Padhan, N. B. & Pandit, R. An analytical and computational study of the incompressible toner–tu equations. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 444, 133594 (2023).

Kiran, K. V., Gupta, A., Verma, A. K. & Pandit, R. Irreversibility in bacterial turbulence: insights from the mean-bacterial-velocity model. Phys. Rev. Fluids 8, 023102 (2023).

Mukherjee, S., Singh, R. K., James, M. & Ray, S. S. Intermittency, fluctuations and maximal chaos in an emergent universal state of active turbulence. Nat. Phys. 19, 891–897 (2023).

Padhan, N. B., Kiran, K. V. & Pandit, R. Novel turbulence and coarsening arrest in active-scalar fluids. Soft Matter 20, 3620–3627 (2024).

Padhan, N. B., Vincenzi, D. & Pandit, R. Interface-induced turbulence in viscous binary fluid mixtures. Phys. Rev. Fluids 9, L122401 (2024).

Rana, N. et al. Defect turbulence in a dense suspension of polar, active swimmers. Phys. Rev. E 109, 024603 (2024).

Kiran, K. V., Kumar, K., Gupta, A., Pandit, R. & Ray, S. S. Onset of intermittency and multiscaling in active turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 088302 (2025).

Ramaswamy, S. The mechanics and statistics of active matter. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 1, 323–345 (2010).

Fodor, É. et al. How far from equilibrium is active matter? Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 038103 (2016).

Vicsek, T. & Zafeiris, A. Collective motion. Phys. Rep. 517, 71–140 (2012).

Tailleur, J. & Cates, M. E. Statistical mechanics of interacting run-and-tumble bacteria. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 218103 (2008).

Aranson, I. S. Active colloids. Phys. Uspekhi 56, 79 (2013).

Driscoll, M. & Delmotte, B. Leveraging collective effects in externally driven colloidal suspensions: experiments and simulations. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 40, 42–57 (2019).

Zöttl, A. & Stark, H. Emergent behavior in active colloids. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 28, 253001 (2016).

Elgeti, J., Winkler, R. G. & Gompper, G. Physics of microswimmers-single particle motion and collective behavior: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 78, 056601 (2015).

Yeo, K., Lushi, E. & Vlahovska, P. M. Collective dynamics in a binary mixture of hydrodynamically coupled microrotors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 188301 (2015).

Nguyen, N. H., Klotsa, D., Engel, M. & Glotzer, S. C. Emergent collective phenomena in a mixture of hard shapes through active rotation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 075701 (2014).

Goto, Y. & Tanaka, H. Purely hydrodynamic ordering of rotating disks at a finite Reynolds number. Nat. Commun. 6, 5994 (2015).

Kokot, G. et al. Active turbulence in a gas of self-assembled spinners. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 12870–12875 (2017).

Haldar, A., Sarkar, A., Chatterjee, S. & Basu, A. Active xy model on a substrate: density fluctuations and phase ordering. Phys. Rev. E 108, 034114 (2023).

Haldar, A., Sarkar, A., Chatterjee, S. & Basu, A. Mobility-induced order in active xy spins on a substrate. Phys. Rev. E 108, L032101 (2023).

Kushwaha, D. & Mishra, S. From flocking to condensation: Collective dynamics in binary chiral active matter. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Appl. 677, 130897 (2025).

Zhang, J., Alert, R., Yan, J., Wingreen, N. S. & Granick, S. Active phase separation by turning towards regions of higher density. Nat. Phys. 17, 961–967 (2021).

Dauchot, O. Turn towards the crowd. Nat. Phys. 17, 883–884 (2021).

Fily, Y., Baskaran, A. & Marchetti, M. C. Cooperative self-propulsion of active and passive rotors. Soft Matter 8, 3002–3009 (2012).

Riedel, I. H., Kruse, K. & Howard, J. A self-organized vortex array of hydrodynamically entrained sperm cells. Science 309, 300–303 (2005).

Petroff, A. P., Wu, X.-L. & Libchaber, A. Fast-moving bacteria self-organize into active two-dimensional crystals of rotating cells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 158102 (2015).

Drescher, K. et al. Dancing volvox: hydrodynamic bound states of swimming algae. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 168101 (2009).

Tan, T. H. et al. Odd dynamics of living chiral crystals. Nature 607, 287–293 (2022).

Kokot, G. & Snezhko, A. Manipulation of emergent vortices in swarms of magnetic rollers. Nat. Commun. 9, 2344 (2018).

Soni, V. et al. The odd free surface flows of a colloidal chiral fluid. Nat. Phys. 15, 1188–1194 (2019).

Han, K. et al. Emergence of self-organized multivortex states in flocks of active rollers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9706–9711 (2020).

Sabrina, S., Spellings, M., Glotzer, S. C. & Bishop, K. J. Coarsening dynamics of binary liquids with active rotation. Soft Matter 11, 8409–8416 (2015).

Pandit, R. et al. An overview of the statistical properties of two-dimensional turbulence in fluids with particles, conducting fluids, fluids with polymer additives, binary-fluid mixtures, and superfluids. Phys. Fluids 29, 111112 (2017).

Boffetta, G. & Ecke, R. E. Two-dimensional turbulence. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 44, 427–451 (2012).

Grzybowski, B. A., Stone, H. A. & Whitesides, G. M. Dynamic self-assembly of magnetized, millimetre-sized objects rotating at a liquid–air interface. Nature 405, 1033–1036 (2000).

Pal, N., Perlekar, P., Gupta, A. & Pandit, R. Binary-fluid turbulence: signatures of multifractal droplet dynamics and dissipation reduction. Phys. Rev. E 93, 063115 (2016).

Perlekar, P., Pal, N. & Pandit, R. Two-dimensional turbulence in symmetric binary-fluid mixtures: coarsening arrest by the inverse cascade. Sci. Rep. 7, 44589 (2017).

Padhan, N. B. & Pandit, R. The Cahn–Hilliard–Navier–Stokes framework for multiphase fluid flows: laminar, turbulent and active. J. Fluid Mech. 1010, P1 (2025).

Perlekar, P., Benzi, R., Clercx, H. J., Nelson, D. R. & Toschi, F. Spinodal decomposition in homogeneous and isotropic turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 014502 (2014).

Doostmohammadi, A., Ignés-Mullol, J., Yeomans, J. M. & Sagués, F. Active nematics. Nat. Commun. 9, 3246 (2018).

Alexakis, A. & Biferale, L. Cascades and transitions in turbulent flows. Phys. Rep. 767, 1–101 (2018).

Frisch, U. On the singularity structure of fully developed turbulence. Turbulence and Predictability in Geophysical Fluid Dynamics and Climate Dynamics (1985).

Frisch, U. Turbulence: the Legacy of A.N. Kolmogorov (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Kolmogorov, A. Dokl. akad. nauk. SSSR 30, 299–303 (1941).

Kolmogorov, A. N. The local structure of turbulence in incompressible viscous fluid for very large Reynolds numbers. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 434, 9–13 (1991).

Perlekar, P. & Pandit, R. Statistically steady turbulence in thin films: direct numerical simulations with Ekman friction. N. J. Phys. 11, 073003 (2009).

Batchelor, G. K. The Theory of Homogeneous Turbulence (Cambridge University Press, 1953).

Pandit, R., Perlekar, P. & Ray, S. S. Statistical properties of turbulence: an overview. Pramana 73, 157–191 (2009).

Dunkel, J. et al. Fluid dynamics of bacterial turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 228102 (2013).

Okubo, A. Horizontal dispersion of floatable particles in the vicinity of velocity singularities such as convergences. In Proc. Deep sea research and Oceanographic Abstracts, vol. 17, 445–454 (Elsevier, 1970).

Weiss, J. The dynamics of enstrophy transfer in two-dimensional hydrodynamics. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 48, 273–294 (1991).

Daniel, W. B. & Rutgers, M. A. Topology of two-dimensional turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 134502 (2002).

Reeves, C. J., Aranson, I. S. & Vlahovska, P. M. Emergence of lanes and turbulent-like motion in active spinner fluid. Commun. Phys. 4, 92 (2021).

Hrishikesh, B., Takae, K., Mani, E. & Tanaka, H. Phase separation of rotor mixtures without domain coarsening driven by two-dimensional turbulence. Commun. Phys. 5, 337 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Dynamic interactions between fast microscale rotors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 9926–9927 (2009).

Zhang, B., Sokolov, A. & Snezhko, A. Reconfigurable emergent patterns in active chiral fluids. Nat. Commun. 11, 4401 (2020).

Grzybowski, B. A., Jiang, X., Stone, H. A. & Whitesides, G. M. Dynamic, self-assembled aggregates of magnetized, millimeter-sized objects rotating at the liquid-air interface: macroscopic, two-dimensional classical artificial atoms and molecules. Phys. Rev. E 64, 011603 (2001).

Han, K. et al. Reconfigurable structure and tunable transport in synchronized active spinner materials. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz8535 (2020).

Shields IV, C. W. et al. Supercolloidal spinners: complex active particles for electrically powered and switchable rotation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1803465 (2018).

Friese, M. E., Nieminen, T. A., Heckenberg, N. R. & Rubinsztein-Dunlop, H. Optical alignment and spinning of laser-trapped microscopic particles. Nature 394, 348–350 (1998).

Tsai, J.-C., Ye, F., Rodriguez, J., Gollub, J. P. & Lubensky, T. A chiral granular gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 214301 (2005).

Sabrina, S. et al. Shape-directed microspinners powered by ultrasound. ACS Nano 12, 2939–2947 (2018).

Farhadi, S. et al. Dynamics and thermodynamics of air-driven active spinners. Soft Matter 14, 5588–5594 (2018).

Huang, B., Ramanis, Z., Dutcher, S. K. & Luck, D. J. Uniflagellar mutants of chlamydomonas: evidence for the role of basal bodies in transmission of positional information. Cell 29, 745–753 (1982).

Brokaw, C., Luck, D. & Huang, B. Analysis of the movement of chlamydomonas flagella: the function of the radial-spoke system is revealed by comparison of wild-type and mutant flagella. J. Cell Biol. 92, 722–732 (1982).

van Kan, A., Favier, B., Julien, K. & Knobloch, E. Spontaneous suppression of inverse energy cascade in instability-driven 2-d turbulence. J. Fluid Mech. 952, R4 (2022).

Cates, M. E. & Tjhung, E. Theories of binary fluid mixtures: from phase-separation kinetics to active emulsions. J. Fluid Mech. 836, P1 (2018).

Puri, S. Kinetics of phase transitions. In Kinetics of phase transitions, 13–74 (CRC Press, 2009).

Verma, M. K. Energy Transfers in Fluid Flows: Multiscale and Spectral Perspectives (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Canuto, C., Hussaini, M. Y., Quarteroni, A. & Zang, T. A. Spectral Methods: Evolution To Complex Geometries and Applications to Fluid Dynamics (Springer Science & Business Media, 2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank V.K. Babu, K.V. Kiran, E. Knobloch, and A. Jayakumar for discussions, the Anusandhan National Research Foundation (ANRF), the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB), and the National Supercomputing Mission (NSM), India, for support, and the Supercomputer Education and Research Centre (IISc) for computational resources. The authors would like to thank the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Cambridge, for support and hospitality during the program Anti-diffusive dynamics: from sub-cellular to astrophysical scales, where some of the work on this paper was undertaken; this work was supported by EPSRC grant EP/R014604/1.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.B. Padhan and R. Pandit conceived the project. N.B. Padhan and B. Maji designed and implemented the computational pipeline, performed numerical experiments, and analyzed the results. R. Pandit supervised the study, secured funding, and contributed to the analysis. All authors contributed to the preparation and writing of the manuscript. The authors confirm that all contributors were appropriately acknowledged and that the work reflects equitable collaboration among researchers from different institutions and career stages. The study followed ethical standards for authorship, data handling, and scientific integrity.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maji, B., Padhan, N.B. & Pandit, R. Emergent turbulence and coarsening arrest in active-spinner fluids. Commun Phys 8, 488 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02437-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02437-y