Abstract

Artificial intelligence can solve complex scientific problems beyond human capabilities, but the resulting solutions offer little insight into the underlying physical principles. One prominent example is quantum physics, where computers can discover experiments for the generation of specific quantum states, but it is unclear how finding general design concepts can be automated. Here we address this challenge by training a transformer-based language model to create human-readable Python code that generates entire families of experiments. The model is trained on millions of synthetic examples of quantum states and their corresponding experimental blueprints, enabling it to infer general construction rules rather than isolated solutions. This strategy, which we call meta-design, enables scientists to gain a deeper understanding and to extrapolate to larger experiments without additional optimization. We demonstrate that the approach can rediscover known design principles and uncover previously unknown generalizations of important quantum states, such as those from condensed-matter physics. Beyond quantum optics, the methodology provides a blueprint for applying language models to interpretable, generalizable scientific discovery across disciplines such as materials science and engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Quantum physics is a notoriously unintuitive field of study. Despite this, it has developed to a point at which some of its most counterintuitive effects—such as entanglement—could become the basis of a new generation of technological development. These applications include quantum imaging1,2,3,4, quantum metrology5,6,7, quantum communication8,9, quantum simulation10,11 and quantum computation12. Due to difficulties in manually designing experimental setups, researchers have started to utilize algorithmic optimization and artificial intelligence (AI) techniques to discover experimental setups in quantum physics13.

AI techniques have been previously applied to the search for experimental setups in quantum physics14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22, nanophotonic structures23,24,25,26 and quantum circuits27,28,29,30,31. In all of these works, the algorithm produces only a single solution, often surpassing designs by human experts. For example, for a given target quantum state, a machine could design the experimental setup that creates the state, but the interpretation and generalization of the results is left to the researcher and is often an exceptionally difficult challenge, if possible at all.

In this work, we introduce meta-design. Instead of designing one solution for a single target (that is, one experimental setup for the creation of one quantum state), we train a sequence-to-sequence transformer to generate a meta-solution in the form of Python code. A meta-solution solves an infinitely large class of targets (a class of quantum states) by generating different experimental setups for different system sizes.

From a software engineering perspective, our approach can be described as the automated discovery of meta-programs, programs that generate or transform other programs32. In our case, the discovered meta-solution generates different programs that construct solutions for an entire class of targets.

Transformer architectures have demonstrated remarkable success in solving a wide range of mathematics and physics reasoning tasks; refs. 33,34 show that a transformer-based sequence-to-sequence model can tackle symbolic math problems such as symbolic integration, differential equations and symbolic regression. AlphaGeometry35 has achieved remarkable performance in solving geometry problems at an olympiad level36, finding that by training transformers on synthetic data, they can accurately predict the Lyapunov functions of polynomial and non-polynomial dynamical systems. In the field of theoretical high-energy physics37, transformers were applied to compute scattering amplitudes. Furthermore, a transformer model38, when trained on symbolic sequence pairs, can correctly predict the squared amplitudes of Standard Model processes. Language models have also been used in quantum simulation39, although not as a generative model for symbolic language as in our or the other works mentioned here.

In recent years, automated code synthesis with large language models has been very promising and powerful, and it fits more naturally with our work. Building on systematic baselines such as program synthesis with large language models40, the field has advanced through large-scale sampling and clustering in AlphaCode41, evolutionary search loops in FunSearch42 and AlphaEvolve43, and reinforcement-learning refinement in StepCoder44. Our technique differs from other automated code synthesis approaches in the purpose of the generated code: each program describes a generalization of solutions to a class of design tasks in physics. For that, it has to learn the underlying physical design principles from data and apply them to output a meta-solution. The resulting Python codes can then be read by humans, who can directly learn these general design principles from the readable code. The readability of the code representation helps to uncover the underlying patterns in the class of solutions. Therefore, our technique is a step towards AI methods that can help gain a new understanding in physics45,46,47. In that sense, the meta-design idea shares technical details with the field of program synthesis; however, when applied for automated scientific discovery, it offers fundamentally new insights that are very challenging to obtain with other known techniques.

Background quantum optics

We choose the design of quantum optics experiments as a proof of concept and point to the potential in applying the approach in other fields. Quantum optics is concerned with photons, the fundamental particles of light. A photon can have different polarization modes, for example, horizontal (mode 0) or vertical (mode 1). A basic property of quantum particles is that they can be in a superposition of multiple modes, that is, they can be considered to be two things simultaneously. The state \(| \psi \rangle\) of one photon in equal superposition can be expressed in Dirac notation as

We omit the normalization factor for all quantum states shown in this work for readability. It can be assumed that all states are normalized. Another important concept is entanglement, where multiple photons are in a state that cannot be described independently, such as a three-particle superposition in which either all particles are in mode 0 or all are in mode 1:

This state is called a Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger (GHZ) state48,49.

In quantum optics, highly entangled states can be created by combining probabilistic photon-pair sources. The number of possible experimental setups increases combinatorially with the number of photons for a given target state. This makes it very difficult to manually design experiments, and thus, computational techniques have been successfully applied to the problem20. For sufficiently large systems, these tasks become too difficult even for current methods as they become too computationally expensive (Fig. 1, right).

Left: our process takes the first three states from a class of target quantum states and—when successful—produces a Python program that generates the correct experimental setup for arbitrary system sizes. For this, a sequence-to-sequence transformer is trained purely on randomly generated pairs of sequences. Right: designing an experimental setup that produces a target quantum state is fast for small particle numbers, but the computational cost grows rapidly with system size. Calculations of floating point operations per second (FLOP) counts are shown in Supplementary Section 1.

Meta-design

We introduce meta-design, the idea of generating a single meta-solution that can solve a whole series of problems (in our case, for the design problems of quantum states with increasing particle number). We define meta-solutions as Python programs that generate blueprints of multiple experimental setups (Fig. 1), for example, a function construct_setup(N), which constructs valid setups for a growing system size N = 0, 1, 2…. In the quantum optics example, the code makes calls to a function defined in the software package PyTheus to generate and simulate the setups20. There is no explicit limitation on the syntax or language of the script used. We train a sequence-to-sequence transformer on synthetic data to translate from a class of quantum states to Python code and sample the model to discover meta-solutions for a selection of 20 classes of quantum states.

Meta-design for quantum experiments

A famous class of quantum states are the GHZ states (Fig. 1, left). They are superpositions in which all particles are either in mode 0 or in mode 1 (equation (2)), with an increasing number of photons (here 4, 6, 8…). Because the experimental setups are based on photon-pair sources, only an even number of photons can be created. We now aim to find a program construct_setup(N) that generates the correct experimental setup for creating GHZ states for a given particle number 2N + 4. This is possible because the GHZ states follow a specific pattern. The solution to the problem is shown in Fig. 1. After constructing the setup, we can compute the expected quantum state that emerges at the detectors. The code shown in Fig. 1 will generate the correct experimental setups for arbitrarily high particle numbers. This code can express the correct experiments for an entire class of quantum states. The goal of this work is to show that it is possible to use language models for the discovery of programs, which solve classes of quantum states such as the GHZ state.

Synthetic data generation

On an abstract level, we can describe the subject of our work as dealing with two sequences: A (a list of three quantum states) and B (Python program). Direction B → A (computing the resulting quantum states from experimental setups) follows clear instructions and can be considered easy. Direction A → B is highly non-trivial. Designing experiments can be very difficult because it usually requires an optimization process even for a single target20 and no general method for discovering the construction rules (Python code) is established. An instructive example of this asymmetry is the problem of finding an integral versus a derivative of a mathematical function. This has been previously explored33. As there exist clear rules for differentiation, they could generate a large number of random functions and compute their derivatives. They then trained a sequence-to-sequence transformer to translate in the reverse direction, which is the more difficult task of integration.

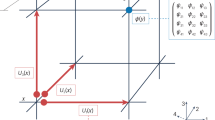

Similar to the approach in ref. 33, we train a sequence-to-sequence transformer to translate in the hard direction (from quantum states to Python code). Because the opposite direction is a straightforward computation, we can produce a large amount of data to train the model by generating random codes (Fig. 2). Our training data consist of two sequences for each sample. The process of translating sequence A (list of states) to sequence B (meta-solution in form of Python code) is the difficult direction, which the model is trained to do.

Using a simple set of rules, we generate a random Python program, which contains instructions for how to set up an experiment. Each program contains the integer index N. This means that the code will result in a different experimental setup for each value of N. Simulating the experiment for N = 0, 1, 2, we produce three states (Fig. 2). After computing the states, sequence A has the form [state 1] [state 2] [state 3] and sequence B is [Python code]. and are the start-of-sequence and end-of-sequence tokens, respectively, and is a separation token. Figure 6 shows a full example for how a training sample is generated and tokenized. We curate a vocabulary (shared by both sequences) for the tokenization. Supplementary Section 2.1 provides further details on tokenization. The maximum length for both sequences during data generation is 640 tokens. We spent approximately 50,000 CPU hours generating 56 million samples.

For the model to successfully generalize to unseen targets, it is advisable to select the distribution of the synthetic data carefully50. A simple example is that a model trained on random samples containing states with three polarizational modes can have difficulties solving a task containing states with only two modes, even though this would be expected to be easier, because it is a subspace. To ensure performance on a diverse range of possibly interesting subspaces, we generate separate datasets at different levels of difficulty and specialization (length of states and codes, number of modes and constraints on phase parameters) and combine them into one final training dataset.

Training (learn A → B)

The transformer is an autoregressive model designed to predict a probability distribution over the vocabulary for the next token given all previous tokens. A readily trained model can then be used to generate tokens by sampling tokens from the distribution and adding them to the sequence one after the other. We train a model of a standard encoder–decoder transformer architecture51, with pre-layer normalization52. We choose the dimensions nemb = 512, nlayer = 18 and nheads = 8. We use learned positional encoding 53, as we are not attempting to apply our model to unseen lengths. The model has approximately 133 million parameters and is trained from random initialization for 750,000 steps with a batch size of 256 (approximately 2.5 epochs on a dataset of 56 million samples). The learning rate of the Adam optimizer54 was 10−4 for the first epoch and was then lowered to 10−5. The training was performed on four A100-40GB GPUs.

In addition to training a transformer from scratch, we also fine-tuned a pretrained large language model (Llama-3 8B) on our code generation task using parameter-efficient QLoRA. Although this approach achieved promising results, it did not outperform the purpose-trained transformer (Supplementary Section 3 provides details on the implementation and Extended Data Fig. 1 shows the results).

Results

Application to selected quantum state classes without known solutions

Our goal is now to apply the trained model to targets for which the code (sequence B) is unknown. Randomly generated data are abundant and, thus, useful for training our model, but our aim is to discover codes for quantum state classes of particular interest (because of particular mathematical or physical properties). We compiled 20 target classes based on quantum states found in ref. 20—all of these states have exceptional properties that have been studied previously, for example, in the context of quantum simulations or quantum communication. The first three states of each target class are explicitly shown in Supplementary Information. They are expressed as strings in the same way in which they are given to the model as input.

For 4 of the 20 targets, meta-solutions were manually crafted by researchers in the past. For 16 of the 20 target classes, no meta-solution was known before our work. Furthermore, we do not even know whether a solution can exist at all with the quantum-physical resources we provide (for example, number of particles necessary to realize a state, and the amount of quantum entanglement). Thus, every meta-solution for these 16 classes is not a rediscovery but a genuine, unbiased discovery.

Hypothesis generation

We let the model produce hypotheses for possible meta-solutions by giving the first three states of a target class as an input sequence. For each target, we can generate many varying predictions by picking randomly from the most likely next tokens with top-p sampling (p = 0.5 and temperature is 0.2 (refs. 55,56)) for 4 h on one RTX 6000 GPU, which produces 800–2,500 samples (depending on the target class) at a speed of ~25 tokens per second. We evaluate the resulting codes by executing them to produce experimental setups for N = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 (training data were generated only for N = 0, 1, 2). We compute the states produced by these setups and their fidelity with respect to the corresponding target state. The fidelity ranges from 0 (orthogonal to target) to 1 (perfect match). In Fig. 3, we show the fidelities of the best sample for 14 of the 20 target classes.

We show the resulting fidelities of the best code produced for 14 of the 20 target classes. The fidelity ranges from 0 (orthogonal to target) to 1 (perfect match). The green line represents the six target classes for which our approach produces code that correctly extrapolates beyond the first three elements. The blue lines show classes for which the best generated codes have fidelity of one for the first three elements of the class, but do not extrapolate beyond. These cases are interesting as the model is still successful in generating a code that matches the three states provided as an input sequence, but the output for N ≥ 3 does not match what we expect. The orange and red lines are representatives of the 8 cases, for which the model was not able to predict correct solutions up to N = 3. The full table of the target classes with their maximum correct N is shown in Supplementary Information, which also contains an extended version of this plot for all 20 classes and for values of N up to 7 (Extended Data Fig. 2).

Here a majority of the sampling time is spent on model inference, whereas computing the fidelities for N = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 is relatively fast. Evaluating fidelities for much larger scales (such as N = 20) can take substantially more time. For this reason, we only include N = 3, 4 as an initial test for correct extrapolation. Successful samples are then evaluated for higher N as well. In Extended Data Figs. 3–5, we show the distribution of fidelities for all the generated samples and how they compare with the training data. We see that for the successful classes, more than 1% of the produced codes are correct, which means that a shorter sampling time would have sufficed.

We found that our trained model produces a syntactically valid code for all the target classes at low temperatures, even if they do not generate the correct states. This is not obvious, as there are many ways in which a randomly generated, syntactically correct code can still be invalid.

Successful meta-design of codes (6 out of 20 cases)

Before training the model, we prepared a set of 20 classes of quantum states as targets for our method. All the target classes we consider here have wave functions that can be expressed as a function \(| \psi (N)\rangle\) of a positive integer N. We require the number of particles in \(| \psi (N)\rangle\) to be ≤2N + 4, the maximum system size allowed during data generation.

In Fig. 3, we show the fidelities of the best sample for 14 of the 20 target classes. The best sample is chosen by filtering for samples with the highest N such that all fidelities up to order N are equal to one and then choosing the one with the highest average fidelity for all N ≤ 4. We find six target classes that our model can solve perfectly. For these classes, the output extrapolates beyond what the model was trained to do, that is, match the states for N = 0, 1, 2.

For four well-known classes (GHZ, W, 2d-Bell, and 3d-Bell), construction rules with 2N + 4 particles are known; these serve as a baseline check of our method. Our model rediscovered all four meta-solutions of these states.

Most importantly, two of the six classes our method solves were previously unknown and, thus, constitute genuine discoveries. The first previously unknown case is the general spin-\(\frac{1}{2}\) state. There, no two neighbouring spin-ups appear in the ground state. In Rydberg-atom experiments, this situation occurs due to the Rydberg blockade20,57; however, it was previously unknown how to build such a class of entangled states for photonic systems. The second novel class contains the states of the famous Majumdar–Ghosh model in condensed-matter physics. In this one-dimensional Heisenberg chain, the value of the next-nearest-neighbour interaction is half the value of the nearest-neighbour antiferromagnetic exchange interaction20,58. The experimental setups generated by our meta-solutions are shown in Fig. 4 (the top two rows).

In the top two rows, we show two previously unknown constructions for the spin-\(\frac{1}{2}\) states and the Majumdar–Ghosh states (described in more detail in ref. 20). For each of the two examples, the code produces the correct experimental setup for the three states used to prompt the model, as well as for higher particle numbers, indicating that the model was able to pick up on the pattern and write the correct code for the entire class of states. We highlight the ‘building blocks’ in green, which are repeated multiple times as the particle number grows (stemming from lines written in the for loop). The bottom row shows a code for the Dyck 1 state. The setups generated by this code produce the correct state up to the third iteration, but are missing terms for indices N > 2. This means that the model was able to solve the task it was trained to do (match the first three states), but failed at the meta-task of picking up on the pattern we intended it to match beyond the first three examples. It is also notable that in contrast to the other two examples, all setups produced for the Dyck 1 state also contained additional crystals that did not actually contribute to the resulting quantum state. We have omitted them by masking them by a grey rounded rectangle.

Codes with unexpected generalizations (6 out of 20 cases)

In these cases, the model produces code that generates the correct states for the first three elements but then yields states that deviate from the intended pattern. These cases are interesting to examine because the model successfully performs the task it was trained for, as the first three states match the input sequence. The fact that it does not continue to match the target beyond N = 3 is due to a degree of ambiguity that exists for the continuation of any infinite sequence if only a finite number of elements is given. One way to reduce (but not remove) this ambiguity in our application would be to train the model on more than three elements, which has to be traded off with an additional computational cost due to a longer sequence length. Further, the output is highly influenced by synthetic data. The model will be more likely to produce an output that closely fits the data distribution it was trained on. One example—the Dyck 1 states—is shown and analysed in Fig. 4. This is an example that does not follow the intended pattern for N ≥ 3, but produces valid states regardless, which randomly generated experimental setups generally do not do. There is potential in examining these cases in more detail to see if the pattern they follow is interesting from the physics side, as they might represent new unexplored classes of quantum states.

Codes that fail to match the first 3 states (8 out of 20 cases)

Four classes match the first two states of the input. Another four classes only match the first state of the input states. There were no examples in which the model could not match any input states. These also include cases for which the setups generated by the output code do not produce a valid quantum state at higher indices N. These cases could be either too complex for the model to give the correct prediction, or generalizations cannot exist at all for physical reasons, given the experimental resources we provide (for example, the total size of the setup). We have found, after analysing our results and testing with direct optimization algorithms, that, for example, the GHZ3d × GHZ3d state is not achievable in the six-particle case without additional ancillary photons, meaning that this would not be a solvable task, no matter how well the model is trained.

Additional application to design of quantum circuits and quantum graph states

To show that the meta-design can be useful in other fields, we also applied it to finding codes for circuit and graph state design, which can be implemented on existing quantum computing platforms. Details on data generation and training can be found in the Methods section.

Quantum circuits

Quantum circuit diagrams are an abstract representation of qubits and the transformations that are applied to them in the form of quantum gates, reminiscent of logic gates in classical computing59. These transformations are unitary and can act on one qubit (for example, Pauli gates or Hadamard gates), two qubits (for example, CNOT or controlled-Z) or three qubits (for example, Toffoli gates or Fredkin gates).

We can also express quantum circuits as code with functions corresponding to specific gates and arguments corresponding to the qubits the gate is applied to (Fig. 5, blue boxes).

a, Output codes (blue boxes, left) of a model trained for the quantum circuit design. We draw the circuit diagram for N = 1, 2, 3. Computation of the resulting states confirms that each of the codes (GHZ, Affleck–Kennedy–Lieb–Tasaki (AKLT) and Majumdar–Ghosh (MG)) correctly produces the corresponding target states, even for N = 3, which shows that the code extrapolates beyond the training scale (N = 0, 1, 2). b, Output codes (blue boxes, left) of a model trained for the quantum graph state. We draw the generated graphs for N = 1, 2, 3. Computation of the resulting states confirms that each of the codes (linear, ring and star) correctly produces the corresponding target states, even for N = 3, which shows that the code extrapolates beyond the scales that are seen during training (N = 0, 1, 2).

We tested the trained model on the state classes from the main task and successfully discover codes for some of them (Bell, GHZ, Affleck–Kennedy–Lieb–Tasaki and Majumdar–Ghosh). We visualize some of the solutions in Fig. 5. We show a more detailed plot of the tested classes in Extended Data Fig. 3. The target states are also expressed as strings in Supplementary Tables 6 and 7.

Quantum graph states

Graph states are a type of entangled quantum states that serve as a universal resource for measurement-based quantum computation60. Graph states are represented as graphs, where each node corresponds to a qubit initialized in the superposition \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(| 0\rangle +| 1\rangle )\) and is entangled with its neighbours through controlled-Z gates.

We can express the codes for generating classes of graph states by using the same syntax as quantum circuit design and restricting possible gates to the controlled-Z gate.

We show that the model can write code for the three well-known classes of graph states, namely, linear, ring and star (Fig. 5).

The target states are also expressed as strings (Supplementary Table 8).

Discussion

We demonstrate how a language model can create human-readable Python code (meta-solutions), which solves an entire class of physical design tasks. We discover previously unknown generalizations of experimental setups for quantum state classes of particular interest. The ability to automatically create generalizations is not only a way of generating and extracting scientific insight but also offers a decisive advantage over conventional AI-driven design in terms of computational costs.

There are a number of interesting open questions for future research. First, in many design questions, objects can be continuously parameterized. In our work, we constrain ourselves to a subset of special numbers (for example, integers or \(\sqrt{2}\)). One can construct arbitrary number approximations by accessing individual integers as tokens; however, this process is highly inefficient. It would be interesting to develop a method that can automatically create arbitrary numbers. Second, our approach works when a large number of code examples for training can be generated efficiently. Because example generation was reasonably fast in our setting, we did not need to optimize the models’ data efficiency. For other questions, examples might be more computationally expensive, and it will be interesting how to optimize the training data efficiency in such cases. Third, at the moment, it is not well understood how the neural scaling law—an empirical law that relates increased training examples, modes sizes and compute times with improved values of the loss value for text-generating LLMs61—translates to symbolic and mathematical solutions such as those in refs. 33,37 and this work. A better understanding of this relation would help improve the model quality, thereby reducing the sample size required to find solutions.

Fourth, more generally, our method is not constrained to quantum physics and can be applied directly to other domains, such as the discovery of new microscopes62, new gravitational wave detectors63, new experimental hardware for high-energy physics64 or the design of new functional molecules65.

At a more abstract level, we see that the application of a powerful intermediate language that can be written and read by both machines and humans can significantly enhance the understandability and generalizability of AI-driven discoveries.

Methods

Details on data generation

The process of data generation is outlined in Fig. 6. The following subsections describe the hyperparameters that are used to create the full training dataset. The source code (and a pseudocode description) can be found on GitHub.

Data generation is split into two parts: the topology workflow (left) and the state workflow (right). In the topology workflow, we find codes that could generate plausible experimental setups. In the state workflow, additional arguments are added to the codes that result in the final states that are created by the experimental setups. The figure follows a real example of a generated sample. The data generation is constrained by a set of hyperparameters (shown in grey boxes). On the bottom, we show the final training data sample as it was used for training the model.

Hyperparameters for data generation

The following hyperparameters are introduced to have more direct control on the distribution of generated data. They are not essential to train a working model. One could also train the model on one very weakly constrained data distribution. We chose to combine multiple datasets with different constraints into the training dataset to make sure that, for example, short, two-dimensional states would be well represented in the training data, which would otherwise not be the case in the most general setting. There are 25 = 32 combinations of the five hyperparameters, resulting in 32 individual datasets with 1.75 million samples each. The final training dataset is generated by combining and shuffling all 32 × 1.75 × 106 = 56 × 106 samples.

Length of code

All codes follow the structure of n0 lines outside of a for loop and then n1 lines inside of a for loop. For long codes, the numbers are constrained by 4 ≤ n0 ≤ 12 and 2 ≤ n1 ≤ 12. For short codes, the numbers are constrained by 4 ≤ n0 ≤ 8 and 2 ≤ n1 ≤ 6

Minimum degree of graphs

DEG1 requires each detector to be connected to at least one photon-pair source, which is the minimum requirement to achieve a valid output state. DEG2 requires each detector to be connected to at least two photon-pair sources, which leads to more advanced entanglement in the resulting quantum state.

Dimensionality

DIM2 creates quantum states made from two modes (qubits) and DIM3 allows for three quantum modes (qutrits) resulting in more advanced states. We chose to include DIM2 states explicitly because they would be rarely generated by a DIM3 distribution, but there are many potentially interesting quantum states that exist in the DIM2 subspace.

Weighted/unweighted

Weighted allows for the introduction of additional phases in the experimental setups, which lead to more advanced interference phenomena. Unweighted restricts the setups to not have any phases. Similar to DIM2/DIM3, we chose to include unweighted codes explicitly so that this subspace would be better represented in the training data.

Maximum length of states

We restricted the number of terms in the output states to limit the length of the sequences that had to be processed by the model, because in our experience, more interesting states tend to have fewer terms. We defined long states to have a maximum of 8, 16 and 32 terms (for N = 0, 1, 2) and short states to have a maximum of 6, 6 and 6 terms (for N = 0, 1, 2).

Background on quantum circuits

A quantum circuit is the quantum counterpart to a circuit of logical gates in classical computer science. It can be represented as a diagram that can be read from left to right (Fig. 5a). A quantum circuit is usually initialized with N qubits in a separable state such as \({| 0\rangle }^{\bigotimes N}\). Gates such as H (Hadamard gate) and CNOT are then consequently applied to produce an entangled state. Designing a quantum circuit for a desired target state can be a difficult task and is approached with different algorithmic methods such as reinforcement learning27,28,30 or variational optimization29,31.

Data generation for additional tasks (quantum circuits and quantum graph states)

Code structure

Each training sample code has the structure:

[1–5 lines of gate functions]

for ii in range ([formula]):

[1–5 lines of gate functions]

[1–5 lines of gate functions]

The number of lines is picked randomly (uniform distribution). In the case of quantum circuits, the type of gate is also picked randomly for each line.

Valid argument formulas

We construct position argument formulas from integers, the scale index and iteration index.

ints = [′-4′,′-3′,′-2′,′-1′,″,′1′,′2′,′3′,′4′]

scale = [″,′+NN′,′+2×NN′]

its = [’-ii’,″,′+ii′,′+2×ii′]

Valid argument formulas for lines outside of the for loop are concatenated combinations of ints and scale that satisfy 0 ≤ f(N) ≤ 2 + 2N for N < 8.

Valid argument formulas for lines inside the for loop are concatenated combinations of ints, scale and its that satisfy 0 ≤ f(N) ≤ 2 + 2N for N < 8 and 0 ≤ ii < range.

For two-qubit gates, we check if the first and second arguments of the gate are equal for any valid combination of N and ii. If they are, we pick a different argument formula for the second argument, to avoid the invalid operation of applying a two-qubit gate to a single qubit.

Computation and expression of states

We compute the resulting states by setting the values for N = 0, 1, 2 and executing the code with IBM’s Qiskit66. We further process the states by filtering out terms with zero amplitudes and dividing all coefficients by the smallest coefficient. This resulted in all states in our training data having integer-valued coefficients. To reduce ambiguity in the expression of the states, we multiply each state with a global phase such that the first coefficient has a positive sign. The states are tokenized according to the vocabulary given in Supplementary Section 2. We then concatenate the states for N = 0, 1, 2 as in the main task, separated by the token.

For the quantum circuit design task, we allow a maximum token sequence length of 640 for the source and target sequence each. For the quantum graph state design task, the maximum token sequence length for the source sequence (states) is set to 1,792, because graph states (including the linear, ring and star graphs) commonly contain all possible kets.

Training

We train two separate models for both tasks (A and B). The training procedure was nearly identical for both. We generate 9.6 million training samples according to the rules specified in the above section. For these additional tasks, we chose slightly smaller models than in the main task. Each model has 12 layers, 8 attention heads and an embedding dimension of 512, resulting in 89 million total parameters. Because of the longer sequence length for task B, we used different batch sizes (task A, 96; task B, 32). Each model was trained for 3 days on one node of eight V100 GPUs with AdamW and a learning rate 2 × 10−4.

Fidelity computation

The fidelity of a quantum state with respect to a target quantum state is a measure of how much the two states overlap. Quantum states are generally represented as elements of a Hilbert space, a vector space equipped with additional properties. The highest possible fidelity is achieved when the two states are exactly the same, giving a value of 1 (the inner product of two identical normalized vectors). The smallest possible value is when the vectors are exactly orthogonal. For example, we define the following one-photon states in bra-ket notation.

We can compute the fidelity of each state with respect to another state. The fidelities of each state with respect to \(| {\psi }_{1}\rangle\) are as follows.

For a multiphoton example, we define the following two normalized four-particle states:

The state \(| \psi \rangle\) contains the two terms of the \(| {\mathrm{GHZ}}_{4}\rangle\) state, but also another third term, which does not contribute to the inner product performed for computing the fidelity:

Extended Data Fig. 4 shows how the terms of a resulting quantum state are derived from a given experimental setup. We compute the fidelity by overlapping this state with the corresponding target state in the same way as demonstrated here.

Data availability

Model checkpoints and training data samples are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14899993 (ref. 67).

Code availability

The code repository for this work is available via GitHub at https://github.com/artificial-scientist-lab/metadesign and Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17287889 (ref. 68).

References

Lemos, G. B. et al. Quantum imaging with undetected photons. Nature 512, 409–412 (2014).

Kviatkovsky, I., Chrzanowski, H. M., Avery, E. G., Bartolomaeus, H. & Ramelow, S. Microscopy with undetected photons in the mid-infrared. Sci. Adv. 6, 0264 (2020).

Moreau, P.-A., Toninelli, E., Gregory, T. & Padgett, M. J. Imaging with quantum states of light. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 367–380 (2019).

Aslam, N. et al. Quantum sensors for biomedical applications. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 157–169 (2023).

Pezzè, L., Smerzi, A., Oberthaler, M. K., Schmied, R. & Treutlein, P. Quantum metrology with nonclassical states of atomic ensembles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 035005 (2018).

Polino, E., Valeri, M., Spagnolo, N. & Sciarrino, F. Photonic quantum metrology. AVS Quantum Sci. 2, 024703 (2020).

DeMille, D., Hutzler, N. R., Rey, A. M. & Zelevinsky, T. Quantum sensing and metrology for fundamental physics with molecules. Nat. Phys. 20, 741–749 (2024).

Flamini, F., Spagnolo, N. & Sciarrino, F. Photonic quantum information processing: a review. Rep. Progr. Phys. 82, 016001 (2018).

Couteau, C. et al. Applications of single photons to quantum communication and computing. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 326–338 (2023).

Aspuru-Guzik, A. & Walther, P. Photonic quantum simulators. Nat. Phys. 8, 285–291 (2012).

Cornish, S. L., Tarbutt, M. R. & Hazzard, K. R. A. Quantum computation and quantum simulation with ultracold molecules. Nat. Phys. 20, 730–740 (2024).

Madsen, L. S. et al. Quantum computational advantage with a programmable photonic processor. Nature 606, 75–81 (2022).

Krenn, M., Erhard, M. & Zeilinger, A. Computer-inspired quantum experiments. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 649–661 (2020).

Krenn, M., Malik, M., Fickler, R., Lapkiewicz, R. & Zeilinger, A. Automated search for new quantum experiments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 090405 (2016).

Knott, P. A search algorithm for quantum state engineering and metrology. New J. Phys. 18, 073033 (2016).

Nichols, R., Mineh, L., Rubio, J., Matthews, J. C. & Knott, P. A. Designing quantum experiments with a genetic algorithm. Quantum Sci. Technol. 4, 045012 (2019).

Wallnöfer, J., Melnikov, A. A., Dür, W. & Briegel, H. J. Machine learning for long-distance quantum communication. PRX Quantum 1, 010301 (2020).

Prabhu, M. et al. Accelerating recurrent ising machines in photonic integrated circuits. Optica 7, 551–558 (2020).

Krenn, M., Kottmann, J. S., Tischler, N. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Conceptual understanding through efficient automated design of quantum optical experiments. Phys. Rev. X 11, 031044 (2021).

Ruiz-Gonzalez, C. et al. Digital discovery of 100 diverse quantum experiments with pytheus. Quantum 7, 1204 (2023).

Goel, S. et al. Inverse design of high-dimensional quantum optical circuits in a complex medium. Nat. Phys. 20, 232–239 (2024).

Landgraf, J., Peano, V. & Marquardt, F. Automated discovery of coupled-mode setups. Phys. Rev. X 15, 021038 (2025).

Molesky, S. et al. Inverse design in nanophotonics. Nat. Photon. 12, 659–670 (2018).

Sapra, N. V. et al. On-chip integrated laser-driven particle accelerator. Science 367, 79–83 (2020).

Ma, W. et al. Deep learning for the design of photonic structures. Nat. Photon. 15, 77–90 (2021).

Gedeon, J., Hassan, E. & Lesina, A. C. Time-domain topology optimization of arbitrary dispersive materials for broadband3D nanophotonics inverse design. ACS Photon. 10, 3875–3887 (2023).

Ostaszewski, M., Trenkwalder, L. M., Masarczyk, W., Scerri, E. & Dunjko, V. Reinforcement learning for optimization of variational quantum circuit architectures. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 18182–18194 (2021).

Nägele, M. & Marquardt, F. Optimizing ZX-diagrams with deep reinforcement learning. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 5, 035077 (2024).

Kottmann, J. S. Molecular quantum circuit design: a graph-based approach. Quantum 7, 1073 (2023).

Zen, R. et al. Quantum circuit discovery for fault-tolerant logical state preparation with reinforcement learning. Phys. Rev. X 15, 041012 (2025).

MacLellan, B., Roztocki, P., Czischek, S. & Melko, R. G. End-to-end variational quantum sensing. npj Quantum Inf. 10, 118 (2024).

Czarnecki, K. & Eisenecker, U. W. Generative Programming: Methods, Tools and Applications (Addison-Wesley, 2000).

Lample, G. & Charton, F. Deep learning for symbolic mathematics. In Proc. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2020).

Kamienny, P.-A., d’Ascoli, S., Lample, G. & Charton, F. End-to-end symbolic regression with transformers. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 10269–10281 (Curran Associates, 2022).

Trinh, T. H., Wu, Y., Le, Q. V., He, H. & Luong, T. Solving olympiad geometry without human demonstrations. Nature 625, 476–482 (2024).

Alfarano, A., Charton, F. & Hayat, A. Discovering Lyapunov functions with transformers. In Proc. 3rd Workshop on Mathematical Reasoning and AI at NeurIPS’23 1–11 (NeurIPS, 2023).

Cai, T. et al. Transforming the bootstrap: using transformers to compute scattering amplitudes in planar N = 4 super Yang–Millstheory. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 5, 035073 (2024).

Alnuqaydan, A. et al. Symbolic machine learning for high energy physics calculations. In Proc. Machine Learning and the Physical Sciences Workshop 1–7 (NeurIPS, 2023).

Melko, R. G. & Carrasquilla, J. Language models for quantum simulation. Nat. Comput. Sci. 4, 11–18 (2024).

Austin, J. et al. Program synthesis with large language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.07732 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Competition-level code generation with AlphaCode. Science 378, 1092–1097 (2022).

Romera-Paredes, B. et al. Mathematical discoveries from program search with large language models. Nature 625, 468–475 (2024).

Novikov, A. et al. AlphaEvolve: a coding agent for scientific and algorithmic discovery. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.13131 (2025).

Dou, S. et al. StepCoder: improve code generation with reinforcement learning from compiler feedback. In Proc. 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL, 2024).

De Regt, H. W. Understanding Scientific Understanding (Oxford Univ. Press, 2017).

Krenn, M. et al. On scientific understanding with artificial intelligence. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 761–769 (2022).

Barman, K. G., Caron, S., Claassen, T. & De Regt, H. Towards a benchmark for scientific understanding in humans and machines. Minds Mach. 34, 6 (2024).

Greenberger, D. M., Horne, M. A., Shimony, A. & Zeilinger, A. Bell’s theorem without inequalities. Am. J. Phys. 58, 1131–1143 (1990).

Pan, J.-W., Bouwmeester, D., Daniell, M., Weinfurter, H. & Zeilinger, A. Experimental test of quantum nonlocality in three-photon Greenberger-Horne-Zeilinger entanglement. Nature 403, 515–519 (2000).

Charton, F. Linear algebra with transformers. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. (2022).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 5998–6008 (Curran Associates, 2017).

Xiong, R. et al. On layer normalization in the Transformer architecture. In Proc. International Conference on Machine Learning 10524–10533 (PMLR, 2020).

Gehring, J., Auli, M., Grangier, D., Yarats, D. & Dauphin, Y. N. Convolutional sequence to sequence learning. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. 70, 1243–1252 (2017).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. In Proc. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2015).

Chen, M. et al. Evaluating large language models trained on code. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.03374 (2021).

Li, R. et al. StarCoder: may the source be with you. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. (2023).

Bernien, H. et al. Probing many-body dynamics on a 51-atom quantum simulator. Nature 551, 579–584 (2017).

Chhajlany, R. W., Tomczak, P., Wójcik, A. & Richter, J. Entanglement in the Majumdar-Ghosh model. Phys. Rev. A 75, 032340 (2007).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010).

Briegel, H. J., Browne, D. E., Dür, W., Raussendorf, R. & Nest, M. Measurement-based quantum computation. Nat. Phys. 5, 19–26 (2009).

Kaplan, J. et al. Scaling laws for neural language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.08361 (2020).

Rodríguez, C., Arlt, S., Möckl, L. & Krenn, M. Automated discovery of experimental designs in super-resolution microscopy with XLuminA. Nat. Commun. 15, 10658 (2024).

Krenn, M., Drori, Y. & Adhikari, R. X. Digital discovery of interferometric gravitational wave detectors. Phys. Rev. X 15, 021012 (2025).

Baydin, A. G. et al. Toward machine learning optimization of experimental design. Nucl. Phys. News 31, 25–28 (2021).

Pollice, R. et al. Data-driven strategies for accelerated materials design. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 849–860 (2021).

Javadi-Abhari, A. et al. Quantum computing with Qiskit. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.08810 (2024).

Arlt, S. Model checkpoints and example training data for ‘Meta-designing quantum experiments with language models’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14899993 (2025).

Arlt, S. Krenn, M. artificial-scientist-lab/metadesign: V1.0. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17287889 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank B. Newman for useful discussions. We also thank F. Charton for sharing valuable insights on the capabilities and current limitations of language models for mathematics. M.K. acknowledges support by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme (ERC-2024-STG, 101165179, ArtDisQ) and by the German Research Foundation DFG (EXC 2064/1, Project 390727645).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: S.A., Y.W. and M.K. Methodology: S.A., H.D., F.L., S.M.X., Y.W. and M.K. Formal analysis: S.A. and M.K. Writing: S.A. and M.K. with input from all others.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Machine Intelligence thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Results for fine-tuned Meta-Llama-3-8B.

We show the resulting fidelities of the best produced code for the 20 target classes in the main task.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Extended version of fidelity vs. particle number.

We show the resulting fidelities of the best produced code for all 20 target classes as an extension of Fig. 3 of the main text. Here we include the fidelities up to N = 7 (18 particles). This shows that the produced codes for the six successful classes (shown in green) are not only correct for small particle numbers but extend beyond.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Overlap between target states and training data.

To evaluate the generalization capabilities of the model, we computed the fidelity (overlap) of all 56M samples in the training data with respect to all target data and show their distribution. This serves to rule out that the full space of possible solutions is explored. Most of the target states for four particles (N = 0) are found by codes in the training data. This is not very surprising, as the space of four-particle states is small enough to be fully explored by a large number of samples. Notably, there is even a single training sample code, which generates setups creating the GHZ states for N = 0, 1, 2, but it does not match the GHZ state for N = 3 (for which the fidelity is 0.25). This means that we would not consider this code a complete solution, as it does not generalize to N≥3. For each sample of the training data, sequence A only includes the four-, six- and eight-particle state (N = 0, 1, 2), but we can find the ten-particle state corresponding to the code by setting N = 3 and computing the resulting setup. The highest of all 56M fidelities is emphasized by a vertical dashed line in each histogram (colored green for perfect overlap).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Fidelities for codes produced during sampling.

Each row corresponds to a target state class. Each column corresponds to the value of N for which the code is evaluated. Columns N = 3 and N = 4 show how the codes perform at generalizing beyond the training range N = 0, 1, 2.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Comparing the maximum overlap with the overlap of the best model output.

We compare the best fidelities of codes found in the training data and codes generated by the model for each target class and for N = 0, 1, 2, 3. Instances where the model prediction matches the target state exactly are marked with a star. For all points, the best model output is better. We also see that the best values from training codes decrease as N grows, but the model output either decreases slower or even stays constant at fidelity 1 for the six classes where the generalizing code was discovered. The grey coloring under the diagonal shows the area where the best training sample would be better than the best model output.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Results for quantum circuits.

We show the best fidelities for each of the target classes that apply to the quantum circuit case (only qubits are permitted, so we do not test three-dimensional states).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Example for computing the resulting quantum state for a given setup.

We show the setup for the spin 1/2 state for six particles. Each panel highlights one configuration of photon-pair sources which can fire at the same time to result in one photon at each detector. All possible configurations are shown. When the six detectors at the top click, we can not know from which configuration of pair-sources the photons have originated. This results in a superposition of all eight possibilities. As different sources can create photons in different modes (blue creating photons in mode 0 and red creating photons in mode 1), the outcome is an entangled state, particularily the six particle spin 1/2 state. The experimental setup is shown with the detectors reordered for visual simplicity. This induces a global permutation of the 0s and 1s of the terms, which can be reversed.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Sections 1–4, Fig. 1 and Tables 1–8.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arlt, S., Duan, H., Li, F. et al. Meta-designing quantum experiments with language models. Nat Mach Intell (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-025-01153-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-025-01153-0