Abstract

Multispecies sustainability and justice can serve as narratives to support and transform nature conservation. Using discourse analysis, we study whether and how three major stakeholders engaged with such narratives to address the representation and agency of swifts (Apus apus). We focus on a debate on mandating ‘swift bricks’ to mitigate the loss of their nesting sites in the UK. Representation refers to acknowledging and articulating the diversity of human and swift interests. Agency refers to recognising and positioning nonhuman actors as subjects of justice. The activist-conservationist gave an imaginary voice to swifts and thus attempted to focus public attention on what these birds demand. The policymakers did not relate to realities other than human and remained impervious to nonhuman rights. We suggest creatively addressing the multispecies perspective in the standard political debates on infrastructural improvements and biodiversity net gain by rethinking the role of built infrastructures for nature conservation and restoration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the biodiversity crisis one of the most pressing challenges for humanity, urgent action is required to reverse biodiversity decline and support ecosystem restoration1,2,3. As cities are now home to more than half of humanity, they are where relationships between people and other species can be renegotiated to find new ways of aligning human-mediated environmental transformation with both conventional and more innovative actions to support biodiversity4,5. Yet, for whom cities are planned remains largely a rhetorical question. Even more broadly, protecting nature is typically justified by human interest, preferences and sensitivities6,7. Humans have altered urban environments, and finding ways to make them more supportive of multiple, nonhuman-specific needs is one of the challenges of the Anthropocene.

Many approaches have been proposed to shift the anthropocentric discourse about cities and help people see and relate to biodiversity in their everyday lives. Examples include biophilic design8,9,10 and the ‘no net loss’ and ‘net gain’ ecological compensation ideals11,12, recently often packaged as nature-based solutions13,14 when there is an ambition to also tackle societal challenges. With ongoing criticism of the dominant anthropocentric and neoliberal urban governance, there have been increasing calls to tackle the societal challenge of making people and cities more caring and inclusive for not only people but also for other species15,16,17,18. New approaches keep emerging to advance the debate regarding the nonhuman beings, such as more-than-human design and planning19, interspecies design20, rewilding cities21 and compassionate conservation22.

This rapidly expanding area of research and practice increasingly acknowledges nonhuman interests23,24,25. It reframes sustainability as multispecies sustainability, regarding whose needs are considered at present and in the future26, and multispecies justice, problematising the question of ‘justice for whom’27,28. Similar ideas have also been advanced as ecological justice, addressing the interests of ecological and human actors simultaneously, and Indigenous environmental justice that highlights how Indigenous worldviews often overcome the duality of people and nature23,29,30,31. Others have also referred to similar ideas as convivial cohabitation32,33,34, positive coexistence35 and interspecies justice and solidarity36,37. One recurrent example of a specific transformative approach that promotes multispecies justice and sustainability is the recognition of nature’s rights38,39. These rights may also be framed as capabilities or entitlements, such as good health and controlling one’s own environment40. A related approach that takes into account a broader perspective on what constitutes justice is recognising the representation and agency of nature28, the issues we explore in this paper in the context of the swifts’ right to nest in human infrastructures.

Representation refers to how to affirm the diverse needs and interests of humans and swifts in decision-making and policies28. It includes communication, co-learning, and ultimately co-becoming, which are all meant to better articulate the needs of all those who constitute the multispecies communities. Representation of nonhuman species is missing from most urban planning cases, giving them no opportunities to be meaningfully involved in decisions. Agency refers to recognising nonhuman actors as subjects of justice, both in the moral and political sense28. As agents, nonhuman beings influence the world, and they should be granted the political power to be part of decision-making processes. Instead of merely using nonhuman actors to support human interests, their agency should allow humans to see them as partners and equal members of the multispecies community. In line with the ideas of multispecies sustainability and justice, we investigate whether and how three major stakeholders in the UK addressed the representation and agency of swifts (Apus apus) in a debate on a seemingly simple measure that might mitigate the loss of the swifts’ nesting sites.

Although globally considered of least concern41, swifts have experienced a continued population decline in many countries. In the UK, their numbers plummeted by 68% between 1995 and 2023, and in 2021, they were red-listed in the UK Birds of Conservation Concern41, signalling a broader trend of the loss of insectivorous and cavity-nesting species. Insulating old buildings and other ways of closing the crevices where swifts used to nest, along with new energy-efficient building techniques and designs, are among the most important reasons for their decline41. To remedy this situation, conservationists suggested that installing ‘swift bricks’ in all new houses across the UK could help restore the population42,43. Swift bricks resemble standard bricks and sit inside a wall, empty inside with a swift-sized entrance hole (Fig. 1). We analyse the narratives invoked in the debate on swift bricks: from Hannah Bourne-Taylor’s initial petition to mandate this solution in November 2022, which was signed by 109,894 human individuals by the end of April 2023, to the parliamentary debate in July 2023. We focus on different standpoints in terms of recognising swifts and their stake in the urban environment. We argue that Bourne-Taylor’s campaign, initiated by her Feather Speech and partly made on behalf of swifts, specific as it may seem, is a telling example of the issues with giving voice and offering nonhumans recognition and procedural justice.

The swift is one of the nonhuman species that make active use of human-made infrastructures. In many places, swifts have come to depend on them and thus have ‘[thrown] in their lot with us’44. Although many people have called for the installation of nest boxes for swifts in the past45, these calls have intensified in recent years as their population continues to decline (for an overview of numerous initiatives that support swifts, see ref. 46). Many different arguments have been used to explain why swifts needed protection, from sentimental to utilitarian44,46,47. Conservation concern for the declines in population has intermingled with references to the special cultural importance of these birds, the amazement and wonder associated with their aerial abilities and extraordinary lifestyles, and ultimately, the instrumental benefits they bring to humans in eliminating certain insects. Some people also touched on the swifts’ rights and claims to space and resources, recognising them as subjects rather than objects, suggesting that they are ‘Not yours: not mine: not anyone’s. They are their own’44. However, it was not until Bourne-Taylor suggested in her Feather Speech what swifts might say if they ‘could fight for their existence with words’ that swifts were symbolically given their own voice.

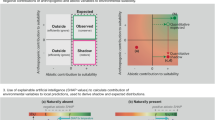

Using discourse analysis, we investigate the language and arguments in documents detailing the interventions of three groups of stakeholders who spoke on the potential to mandate swift bricks in all new housing in the UK. We present the methods we used at the end of the paper, along with the broader context within which this debate emerged, the chronological order of events spurred by the Feather Speech campaign, and the detailed information on the sources analysed and the procedure followed. Meanwhile, directly after the Introduction, we present the Results and Discussion. In the Results section, we highlight the most relevant issues addressed by Bourne-Taylor’s petition, the UK Government in its response to this petition, and the Members of Parliament (MPs) in their debate on whether installing swift bricks should become compulsory in new housing. We assess whether the respective stakeholders recognised nonhuman representation and agency and whether they overcame the dichotomy between people and nature to address the co-production of the environment by the entangled human and nonhuman actors. We discuss how non-standard conservation narratives may not be properly understood by policymakers and politicians, and how to creatively address multispecies perspectives in standard political debates on infrastructural improvements and net gain narratives (for an overview of this paper’s narrative, see Fig. 2).

This paper contributes to the discussion on how nature-based solutions and other presumably biodiversity-supportive actions must be reframed to ensure that those most concerned, human or other, have a say in the decisions made. Focusing on the procedural side of justice, our study explores how ‘voice’ morphs as it becomes politicised in debates and deliberation. Moreover, we interrogate just how humans understand the nature of other species and whose needs or interests these measures are meant to satisfy. Ultimately, this study adds to the debate on the elusive notion of biodiversity net gain, which, although meant to benefit biodiversity, still prioritises human developments and interests.

Results: Will swift bricks become compulsory in new housing in the UK?

Hannah Bourne-Taylor: ‘an alliance with our wild neighbours’

When activist-conservationist Hannah Bourne-Taylor launched the petition to mandate swift bricks in new housing in Britain (5 November 2022 in London), she figuratively gave swifts their voice:

“If a swift could fight for their existence with words, they might say this: (…) I have spiralled above the clouds cloaked in the setting sun, spun through the eyes of ferocious storms, crossed deserts, oceans, continents. For generations my kind has existed, our blood line unbroken for millions of years. And we have screamed in delight at your creativity, innovation, progression. But now we are screaming for you to help us. To look up. To remember you share your home with other kinds. Feathered, furred, finned, scaled, winged. Our shared home is becoming parched of life, destroyed, flooded, licked by flames, ablaze. Through these shared struggles, we only ask for one thing. A safe place to rest after our perilous journey home. You can help us. You can remember your walls also belong to adventurers. You can unblock the holes and make new ones”.

On her own behalf, Bourne-Taylor added: ‘The Feather Speech is not just a campaign aimed at the government or to the people of Britain. It is an alliance with our wild neighbours.’ She did not want people to sign the petition because she asked for it, but because swifts couldn’t. Although the campaign focused on swifts, it addressed other UK red-listed birds: house martins, starlings and house sparrows. In the briefing note published online, Bourne-Taylor42 suggested that ‘a national policy [mandating swift bricks] would be a small and straightforward solution for small urban birds’. As highlighted in the briefing note, the demanded solution would support humans’ relationship with nature: ‘urban birds live so close to us, they provide us with an invaluable connection with nature which is even more relevant when the majority of people in the UK live in urban areas’.

The petition mentioned facts about swifts from a human perspective, including that ‘they’re tidy and quiet neighbours’, ‘iconic and irreplaceable’ and that they ‘define our summers’. The same perspective was prevalent throughout the briefing note that highlighted the connection between swifts and humans: indicating that they nest in ‘our walls’, fly ‘over our skies’, ‘they come home to us’, ‘our home is their home’ and eventually that ‘The birds who share our walls are quite literally our very closest neighbours’.

From the beginning, Bourne-Taylor indicated that existing measures (such as the then-debated biodiversity net gain) did not target swifts or other individual species. The briefing note also referred to official documents, such as the Environment Act, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework Targets (e.g. to ‘ensure biodiversity-inclusive urban planning’), the UK Government’s Environmental Improvement Plan 2023, and the United Nations’ Decade on Ecosystem Restoration.

Finally, the briefing note also mentioned more practical arguments not highlighted in the original petition. It indicated that ‘swift bricks are an existing, low-cost, proven conservation measure’ characterised by permanence and zero maintenance requirements.

UK Government: ‘particular forms of green infrastructure’

In its response to the petition (1 December 2022), the Government wrote: ‘We will not be legislating […] to compel local authorities or developers to include particular forms of green infrastructure in every development’48. This response was based on the presumption that ‘In some high density schemes the provision of ‘swift bricks’ […] might be inappropriate; in other places it could not achieve the desired connectivity for wildlife’. In consequence, the Government suggested that ‘For the natural environment to thrive we need both local authorities and developers to understand the natural characteristics of each site, and to take proportionate and reasonable action relevant to that location’.

According to the Government, existing planning prescriptions could be used in favour of swifts, and previous initiatives of local governments across the UK suggested that those concerned with swifts could implement respective solutions within the existing system. Most notably, in the case of England, the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) introduced a requirement for the planning system to ‘provide biodiversity net gains where possible’. Crucially, ‘opportunities to improve biodiversity in and around developments should be integrated as part of their design, especially where this can secure measurable net gains for biodiversity’ (NPPF, paragraph 187). The Government indicated that swift bricks were already listed in the NPPF ‘as one option for LPAs [Local Planning Authorities] to minimise impacts on biodiversity and provide net gains in biodiversity’. At the same time, the Government admitted that the petition was right in saying that ‘the metric for calculating biodiversity net gain doesn’t include existing nesting sites in buildings, or swift bricks’ and that it only referred ‘to habitat categories as a proxy measure for biodiversity and the species that those habitats support’. This, the Government indicated, would remain in force even after the expected revisions of the biodiversity metric, but the Government ‘would consider how habitat criteria could be updated in future to take account of protected and other important species’.

The other existing provision invoked by the Government as a potential solution alternative to mandatory swift bricks was the Environment Act 2021 and its local nature recovery strategies (LNRSs), soon to be required from all LPAs. LNRSs are supposed to ‘identify locations to create or improve habitat most likely to provide the greatest benefit for nature and the wider environment’. However, as noted in the Debate Pack prepared by the House of Commons Library48, again, this provision is unlikely to benefit swifts because their ‘wide foraging habits’ escape the framing of localised actions.

Parliamentary debate: ‘we must start by quite literally making a home for nature’

MPs are expected to represent the UK public, and the debate in the House of Commons shows that they recognise their constituents’ care for birds. Many MPs frame swift bricks as an exemplary, tangible solution to multiple environmental challenges. On the one hand, humans owe it to swifts: ‘Having learned to live alongside us because we are good partners to them, they are now losing out on that habitat; and we ought to do something about that’ (Robert Courts, Conservative). On the other hand, swifts epitomise broader environmental problems. In the words of Caroline Lucas (Green), ‘If we are to have any chance of changing that terrifying picture, we must start by quite literally making a home for nature—by living once again with a species that has long been our closest neighbour. If the swift goes, it will be its own tragedy, but it will also be symbolic of so much else’. However, the latter approach is ultimately driven by human self-interest:

‘taking care of nature is a way of taking care of ourselves and all the other species with which we are so privileged to share this one precious planet. Mandating the use of swift bricks in new buildings is one of the smallest and simplest steps we could take, but it would symbolise so much more. It would be that first step, but it would also be a symbol of our recognition of deeper interconnectedness’ (Caroline Lucas).

While different MPs assumed the role of stewards of nature to different degrees and they used diverse arguments, the debate showed evident cross-party support for the use of swift bricks in new housing. Some even suggested mandating swift boxes in other types of buildings and extensions of existing residential buildings, going beyond what the petition demanded (Caroline Nokes, Conservative; Kerry McCarthy, Labour). Others went beyond the original demands by suggesting that ‘we must also consider their need to feed by tackling the depletion of insect varieties’ (Helen Morgan, Liberal Democrats). Even the very few MPs who openly spoke against mandating swift bricks still considered it necessary to ‘drive up rates of swift brick installation in new build properties […] as part of efforts to increase biodiversity net gain’ [fragments have been reordered for clarity] (Matthew Pennycook, Labour). MPs seemed to be united in positive sentiments related to swifts, as reflected in their personal memories and stories of wonder and admiration, emphasising the importance of people’s connection to nature. Providing nesting habitats for swifts was seen as ‘a wonderful opportunity to celebrate these birds’ (Siobhan Baillie, Conservative).

This broad support is partly related to the iconic status of swifts, considered ‘amazing’ (Kerry McCarthy), ‘breathtakingly charismatic’ (Robert Courts) and ‘one of nature’s miracles’ (Caroline Lucas). Matt Vickers referred to ‘the public’s concern about losing these iconic birds completely, which would be a huge loss to our country’s biodiversity and culture’. MPs highlighted that other species of birds would benefit from swift boxes, such as house sparrows, house martins, starlings, blue tits and wrens, along with hibernating tortoiseshell butterflies and bees. Caroline Lucas noted that ‘Swifts symbolise the decline of almost all long-distance, insect-eating migrants to the UK’. However, they also acknowledged that ‘the swift brick is needed, because it is niche [sic] to swifts’ (Robert Courts). The most important reasons ‘why swifts merit a specific planning requirement, as opposed to any other creature that is under threat [might be…] first, this is a known problem with an identifiable cause and a practical, straightforward and cost-effective solution. […] Secondly, other species are already protected by planning policy in a way that swifts are not’ (Kerry McCarthy). Finally, as reflected in the debate, not all species are equally welcome, with parakeets, pigeons, and seagulls given as examples of species likely to cause nuisance to human residents, unlike swifts that were considered ‘excellent lodgers’ (Kerry McCarthy). ‘Using bricks would give other species opportunities and would protect swifts from being evicted by more aggressive species’ (Kit Malthouse, Conservative).

From a practical point of view, MPs emphasised that swift bricks are ‘utterly unobtrusive’ (Robert Courts), ‘clean and noise-free’, and ‘a no-brainer in many ways’ that ‘cost little and have a huge impact’ (Matt Vickers, Conservative). They also underlined that swift bricks are ‘welcomed by the public and by developers’ (Matt Vickers), which they supported by examples and survey results. However, MPs emphasised that the multiple bottom-up initiatives of local planning authorities, developers and local swift conservation groups did not match the swifts’ nesting needs and, despite the Government’s suggestions, installing swift bricks was not effectively supported by existing regulations. Many MPs challenged the Government’s response to the petition and underlined that ‘a legal duty to include swift bricks in all new developments is essential to deliver the new level of action that is required to save our swifts’ (Caroline Lucas). They also suggested specific amendments to existing regulations, including the biodiversity net gain metric, ‘by understanding that for a swift, a building is its habitat’ (Robert Courts) or allowing ‘developers to consider whether swift bricks are an efficient way for them to meet their biodiversity targets’ (Kerry McCarthy). These suggestions were welcomed even by the highly sceptical Matthew Pennycook, who suggested that ‘with swift bricks properly scored on the BNG [biodiversity net gain] metric system, the onus would at least be on local authorities and developers to justify not installing swift bricks in each instance across specific sites’. Kerry McCarthy mentioned that as long ago as 3 years earlier she had called on the Government ‘for the building regulations to be revised to make swift bricks compulsory in all new homes’, a request that had been rejected. And yet, despite noticing the rare instance of ‘cross-party unity’, the Government’s representative, Dehenna Davison, closed the debate by saying: ‘it is not something that is being considered by Government at the moment’, ‘not wanting to add unnecessary additional complexity to a service that already faces a great deal of it’.

Discussion

Although the political debate on swift bricks continues (see the subsection on the context of the debate in Methods), the three cases above clearly represent the positions expressed by major stakeholders. Table 1 summarises our interpretation of the stakeholders’ positions regarding the swifts’ representation and agency. While the ecologically reflexive activist-conservationist Hannah Bourne-Taylor claimed to speak on behalf of the swifts, and MPs showed empathy and attentiveness to swifts’ interests, speaking as their stewards, the Government’s response represented a technocratic rationality, with swift bricks framed as part of ‘green infrastructure’ and ‘biodiversity net gain’. Although the Feather Speech may unnecessarily anthropomorphise the birds, Bourne-Taylor herself suggested that it ‘was really more of a song for swifts, an ode for their survival’43.

Both Bourne-Taylor and MPs agreed that swifts are a culturally iconic species that can potentially serve as an ecological umbrella for other species, thus alluding to their social-ecological importance49. Some MPs embraced the idea of the swift brick as a simple gesture that could help the swift population recover and saw it as a rare example of an easy measure to have such an important potential impact. MPs were largely sympathetic towards swifts and swift bricks, reflecting the broader social support captured by books also cited during the parliamentary debate46,47. Still, wary of enforcing any new obligations on developers, the Government and some MPs emphasised the opportunities to protect swifts within the existing legal framework, including via the biodiversity net gain provisions. Meanwhile, both Bourne-Taylor and some MPs highlighted the failures of the existing solutions to provide swifts with nesting sites. Even if the Government were right and swifts would choose not to use some of the bricks that might have been created for them, in this case, they were still not allowed to make these choices themselves.

Adopting a nonhuman perspective is meant to be an evocative conservation argument. It appeals to people’s empathy and attentiveness, trying to understand nonhuman actors, such as swifts, as their own beings whose needs are closely intertwined with those of humans. The language used matters a lot here, especially given that only humans took part in the debate. In a sense, all stakeholders referred to the swifts’ needs and spoke on their behalf. However, it was only the activist-conservationist who gave an imaginary voice to the swifts and, in this way, attempted to focus public attention on what the swifts demand. The example of the debate on swift bricks demonstrates the challenges of adopting a nonhuman perspective as a conservation narrative, which may be one of the reasons why established conservation organisations rarely refer to arguments such as multispecies justice or nonhuman rights. Most importantly, policymakers and politicians seem to be impervious to these rights narratives.

Below, we reflect on why different stakeholders acknowledge or refuse nonhuman representation and agency, offering additional insights into how multispecies justice could be further operationalised in the context of arguments that might speak to a broader range of stakeholders. In particular, we connect to the debate on the value of nature and the underlying worldviews to creatively address a multispecies perspective in standard political debates on infrastructural improvements and net gain narratives. Indeed, politicians and policymakers are so used to hearing standard narratives, including through interaction with established conservation organisations, that they have difficulty engaging with an alternative discourse that refers to nonhuman representation and agency. We hypothesise that had a critical mass of conservationists started using these arguments, policymakers would need to engage with them, too. Strategic exposure to these narratives in the formative stages of respective political debates might help to make a difference. And here is a crucial role to be played by more independent activist-conservationists, such as Hannah Bourne-Taylor.

Being a culturally iconic species, swifts are fortunate enough to attract broader attention to their troubles28,50,51. Unlike some other bird species, such as pigeons, which evolved from a symbol of peace and a rightful urban resident to a ‘rat with wings’52,53,54, swifts are typically considered eligible urban cohabitants. Meanwhile, pigeons provide an emblematic example that reflects a broader trend of banishing species considered ‘pests’ or ‘pollution’, categories which almost any nonhuman actor can fit, ‘unless it is controlled or civilised’53. These may include geese, crows, the Australian white ibis, as well as gulls, parakeets and even starlings, which were mentioned in the parliamentary debate. This links to the distinction between the beneficial and the harmful, which has always been fundamental to the debate on nature conservation. The ‘utterly unobtrusive’ and ‘clean and noise-free’ swift bricks remain a relatively safe option. They do not require any particular sacrifices from humans to make space for other species while providing the additional cultural and insect control services of swifts—humans’ ‘tidy and quiet neighbours’.

As exemplified by the parliamentary debate, as stewards of nature, people may be willing to help birds, but they tend to selectively provide nest boxes to their preferred species (cf.55). Due to their priority status for many humans, the swifts’ case emphasises relationships with particular nonhuman species rather than broader multispecies sustainability26 or multispecies justice27,28. Embracing a multispecies perspective requires ‘the courage to question our most basic cultural narratives’56, most notably pertaining to the human–nonhuman divide. It might acknowledge kinship between humans and nonhuman entities23,57, or at least foster more convivial cohabitation33,58 or positive coexistence59 that acknowledges the nonhuman beings’ needs and capabilities.

Ultimately, what is at stake is not just the conservation/protection of an individual species but a broader acknowledgement of nonhuman rights and claims to space and resources. Acknowledging these rights translates into an obligation for humans to recognise and meet nonhuman needs18. Acknowledging nonhuman rights and agency would correspond with both parties consciously co-shaping or co-creating social-ecological reality, offering a transformative worldview change that lies at the heart of the social-ecological systems concept60,61. Indeed, the beneficial/harmful debate—reflected, for example, in debates on ecosystem services and disservices and the power of nature-based solutions to address human problems6—may favour swifts, but is also a way of reasoning that is fiercely rejected by some swift advocates44.

The Life Framework of values provides a helpful lens regarding the integration of intrinsic, instrumental and relational values in policy- and decision-making61,62, especially given the opportunity to apply it from the reverse nonhuman perspective63. It considers living from, in, with and as nature or its specific components, indicating why they matter to humans (or vice-versa, how humans may be perceived by nonhumans). While Bourne-Taylor tried to evoke a feeling of living as swifts, internalising a nonhuman perspective, MPs expressed the living with swifts perspective when referring to providing nest sites for these birds within human infrastructures. The government’s response is difficult to contextualise here because of its purely anthropocentric perspective and the fact that it treats swifts and their world as external to the world of humans that the government manages. It barely links to living in the broader environment, which the different legal instruments mentioned in the government’s response are meant to address. It also shows how easily the formal recognition of nonhuman rights, and even needs, can be sidestepped, despite these needs often being recognised in law, albeit with many loopholes. Meanwhile, swifts offer a perfect example of a nonhuman actor that has adapted to living with humans. From the swifts’ perspective, a city may be seen as ‘a petrified forest inhabited by strange creatures’45, but only Bourne-Taylor acknowledged this potential way of the swifts’ thinking.

The parliamentary debate, and certainly government policy, failed to acknowledge the stakes of nonhumans regarding different decisions and political choices62. Even when the swifts’ interests were represented, it was rather paternalistic (albeit well-intentioned), as reflected in MPs’ statements, such as ‘They are not here for terribly long, which is why we should give them a nice home to live in’ (Kit Malthouse) or ‘Swifts have been with us for millions of years [sic], and I hope that we can ensure that this remarkable species stays with us for much longer’ (Samantha Dixon, Labour). Perhaps the MPs considered the comforts of people caring for swifts, thus only indirectly acknowledging the swifts’ interests. While Bourne-Taylor’s campaign started with giving swifts a voice, acknowledging them as human co-inhabitants and thus being the closest to a pluricentric perspective, the government and MPs discussed these issues through an anthropocentric lens, leaving space only for the affection for swifts of certain members of the public. This reflects how the participation of many disadvantaged stakeholders is often tokenised, as seen in the cases of children64 or people with disabilities65. Indeed, most humans have difficulty envisioning nonhuman participation or representation other than through appointed guardians58,66, be it a benign steward (MPs) or a self-acclaimed ‘go-between’ (Bourne-Taylor).

Recognising the interests of nonhuman species requires a broader worldview regarding human–nonhuman or multispecies cohabitation59,67. Interestingly, with the progress of more-than-human design, representation increasingly involves ‘the creation of hybrid voices based on an ever-expanding array of beings that come to matter’68. This is shown by multiple examples of imagining exercises and role-playing games within which humans imagine and role-play the other species’ perspectives and use AI, field observations, and interactive agent-based models28,67,69,70. Nonhuman stories might be based on observing their behaviours, an approach that has also supported more-than-human design thinking related to swifts elsewhere71. While most debates remain selective about who is considered to matter enough to be represented, new approaches may be driven by addressing past harms incurred by multiple species in an attempt to repair human relations with the nonhuman actors69. This approach would be particularly relevant in the case of swifts, given that mandating swift bricks was intended to make up for past injustices—the loss of nesting sites due to new building techniques. Ultimately, empathy and attentiveness are always the first steps towards justice.

However, as the case of the demand to mandate swift bricks demonstrates, the nonhuman or more-than-human approach above is distant from the world of formal politics. It is a language and a broader worldview that politicians and policymakers are reluctant to embrace. In its response, the Government used very few counterarguments to directly try to reframe the swifts or their needs. Instead, it sought an elusive ‘biodiversity net gain’ that fits into and reinforces a neoliberal economic approach of biodiversity offsetting72 that has already been shown not to benefit individual species73. Similar problems have been observed in other cases of biodiversity offsetting74,75,76. Moreover, it is ineffective and leaves space for multiple abuses, as evidenced by developers not respecting guidance or even legally binding planning requirements. This raises broader doubts about the delivery of ecological mitigations, enhancements and offsets within the biodiversity net gain framework77. Although Bourne-Taylor and MPs raised similar concerns, the government sees biodiversity net gain as a potential primary solution to the loss of nesting sites, along with other similarly ineffective measures, such as the mention of swift bricks in the Government’s planning practice guidance.

What mattered to politicians in the House of Commons and policymakers in the Government was the political choice of whether decisions should be made in a top-down or a bottom-up manner, i.e. mandating vs leaving it to developers and local authorities to find the best solution for swifts on a case-by-case basis. Labour MPs were particularly sympathetic ‘with the Government’s position that local authorities and developers should not be compelled to include swift bricks in every single housing unit that they respectively authorise or construct’ and keen on allowing ‘for maximum local discretion’ (position summarised by Matthew Pennycook). Meanwhile, Conservative MPs were more eager to support mandating permanent and weather-resistant swift bricks, observing that developers were not necessarily complying with the NPPF guidance on biodiversity net gain and that, at best, they put up ‘wooden boxes here and there that will deteriorate over three or four years and then be gone’ (highlighted by Kit Malthouse). Clearly, the pursuit of economic growth and the interrelated processes of capital accumulation, economic liberty, and urbanisation affect not only the environment in general but also individual species and their rights15,69,78. Meanwhile, one of the challenges that planners and other stakeholders experience when trying to do something out of the ordinary is that the system within which they operate does not grant them the resources or the flexibility to do so28. This may be the case even when there are general guidelines that they could potentially use to support the cause, such as in this example. This underlines the importance of solutions that level the playing field for all stakeholders by mandating swift bricks rather than merely recommending them.

Beyond issues related to environmental values and worldviews, this case provides insights into debates on built, non-biological infrastructure. It differs from discussions about green spaces and more conventional habitat resources and extends the question of multispecies justice even further into the human realm. In this way, it invites multiple stakeholders to rethink the role of constructed infrastructure for nature conservation and restoration. Conventionally understood as ‘artificial’ and largely separate from (and often interfering with) nature, constructed infrastructure is also a place where nonhuman agency could be written into the human experience. Instead of an artificial world where most human constructions—buildings, transportation infrastructure, and so forth—offer little in terms of supporting biodiversity or our relationships with it, repositioning the artificial as something with the potential to also support nonhuman interests may provide an interesting opportunity to think differently about how life-worlds meet.

This perspective, however, remains distant from the current political debate. Legislation and pro-environmental policies are still positioned as having a bearing primarily on the green, not the grey. The opportunity to design for justice may help make an abstract concept more concrete and relatable. Design and the artefacts it creates mediate the capacity to empathise, understand, and, not least, compromise in daily interactions with the many human and nonhuman cohabitants79. While the discourse surrounding nature-based solutions typically focuses on biological components, non-biological components have much to offer, even regarding ecological compensation that underlies biodiversity net gain. Including the functions of non-biological components as nesting sites or potential substrates for soils might be the examples to start with, along with other debates on making human-built infrastructures less detrimental to nonhuman actors (such as preventing bird collisions with windows, powerlines and wind turbines).

Next, we address the question of when ‘nature-based solutions’ are also ‘solutions for nature’. Perhaps most importantly, the question that needs to be addressed in this context is: Whose problems are nature-based solutions meant to solve? While the classical definitions mentioned environmental, social and economic problems, clearly the focus has been on the problems experienced by humans. Our case study shows the potential to broaden this perspective by referring to multispecies justice, treating nature as a partner rather than a tool7,80. Indeed, multispecies justice considerations represent a cutting-edge area for nature-based solutions research, with a particular emphasis on relational thinking and a pluralistic approach to human–nonhuman interests16,28,81.

Our case study connects issues of justice with a broader emotional appeal, connecting nonhuman interests with the design of built, non-biological infrastructure. Could swift bricks that involve the creation of nesting sites for swifts within new human infrastructures be considered nature-based solutions for the sake of providing a just and equitable arrangement of shared multispecies space? Historically, swift nest holes were integrated into buildings to collect their chicks for food46,82. Recent attempts at mandating swift bricks, however, are targeted at benefiting swifts and restoring the habitats they are losing due to changes in human building techniques and broader sterilisation of human habitats. Hence, we explore a nature-based solution that is intended to restore nature for nature’s own sake. We argue that calling this a nature-based solution is as valid as any other intervention intended to protect, restore or provide habitats for nonhuman beings. It shows how the development of infrastructure that serves human needs can also support the interests of nonhuman cohabitants. Unlike in the conventional interpretation of nature-based solutions81,83, mandatory swift bricks would primarily benefit swifts, with any advantages to humans and other species being secondary co-benefits. Similar arguments (and indeed a similar petition and debate) could be made about the loss of insects with the ongoing use of chemical pesticides, which directly threatens the insects themselves, but also other species, such as swifts, who depend on them for their survival.

Further research could explore such an alternative framing of nature-based solutions. Studies could also investigate how the interests of swifts have actually been considered by those local authorities and developers who introduced the respective local requirements or voluntarily installed swift bricks in their new developments, despite the lack of formal requirements. The developers’ role could be explored within the framework of exploratory research on multispecies entrepreneurship, within which humans and nonhumans work as partners to deliver solutions, ultimately promoting nonhuman welfare84.

Finally, the issue of providing nesting sites is perhaps still easier to address—including by adopting a nonhuman perspective—than challenges such as insect availability or pollution, both of which are important interrelated problems for swifts and many other urban birds. While people may be relatively eager to help by providing alternative nesting spaces (and even acknowledge the rights of swifts to such spaces), they may be less likely to make larger sacrifices, such as changing their mobility, food consumption patterns or gardening practices. Nonetheless, the main point that we made in this paper is the need to go beyond technocratic rationalities (represented here by concepts such as biodiversity net gain and offsets) and genuinely recognise the rights of nonhuman species to the shared space, by recognising their representation and agency. Following a relational approach that is intended to overcome the human–nature dualism provides a foundation for a genuine multispecies cohabitation and justice18,31,85.

In conclusion, only Hannah Bourne-Taylor, the activist-conservationist, recognised the swifts’ agency and representation. Reflecting the broader societal perspective44,46,47, the parliamentary debate showed many expressions of admiration for the wonder of nature that the swifts epitomise, but not so much in terms of justice and recognising their rights and agency. Although the debate was initiated by an activist-conservationist who claimed to give voice to swifts, when confronted with formal politics, the questions of representation and agency of swifts receded to the background. The political debate over mandating swift bricks, and thus normalising human–nonhuman cohabitation, at least with regard to certain nonhuman actors, has been dominated by human perspectives on sharing space. While politicians welcomed the idea of humans living with swifts, some were sceptical of normalising it through legislation that might then be translated into an obligation to recognise and meet nonhuman needs. Broader exposure to arguments regarding nature’s representation and agency, particularly those rooted in non-Western and non-anthropocentric worldviews and value systems, might increase the opportunities to include them in political debates. Similarly, broadening the debate on nature-based solutions and biodiversity net gain to cover non-biological components and nonhuman interests would help to make human-built infrastructure less detrimental to nonhuman beings.

Methods

Case study description

The debate on mandating swift bricks emerged because of the broad concern for the fate of swifts, whose populations experienced a particularly acute decline in the UK. Swifts epitomise broader problems of cavity-nesting birds that have adapted to living within human infrastructures. These problems are becoming increasingly acute with the ongoing sterilisation of human habitats, restricting the availability of nesting spaces and food resources for bird species that have adapted to living with humans8,47. Swift bricks have been proposed as a specific solution to the problem of losing nesting sites due to the loss of cavities, which has been linked to factors such as the thermal insulation of buildings86,87. Several local authorities have promoted swift bricks through local planning instruments46. In response to increasing demand, the British Standards Institution issued a specification on designing and installing integral nest boxes88. Ultimately, Hannah Bourne-Taylor’s e-petition no. 626737 demanded that the UK Government mandate swift bricks in all new housing in the UK. The petition was promoted through the broader Feather Speech campaign, which received support from many stakeholders, including the RSPB, Wild Justice, and the Home Builders Federation. Bourne-Taylor has comprehensively documented this campaign43.

The petition, titled: ‘Make swift bricks compulsory in new housing to help red-listed birds’, was initiated on 31 October 2022 and officially launched by Hannah Bourne-Taylor on 5 November 2022 with her Feather Speech in London’s Hyde Park. Once a petition reaches 10,000 signatures, which in this case happened on 10 November 2022, the Government must issue a formal response. The response was provided on 1 December 2022. And once a petition reaches 100,000 signatures, as this one did on 8 April 2023, Parliament is obliged to debate the issue in question. By the time the petition closed on 30 April 2023, it had been signed by 109,894 people. The debate in the House of Commons took place on 10 July 2023. The sole purpose of these parliamentary debates is to discuss the issues raised in the petitions, without any formal voting on the potential implementation of what a petition requested.

The debate in the House of Commons did not put an end to the story, and efforts to promote making swift bricks compulsory have continued. In September 2023, Lord Zac Goldsmith (Conservative) advanced an amendment to the Levelling-up and Regeneration Act of 2023 to add a new clause specifically demanding that swift bricks and boxes be installed in new build developments over five metres in height (giving preference to bricks). Planning authorities would still be able to grant exceptions, but they would need to explain them. Despite broad cross-party support, the Government rejected this amendment. In February 2024, Bourne-Taylor and Lord Goldsmith met with the Secretary of State, Michael Gove, and housebuilding lobby groups. Although the lobby groups did not raise objections to mandating swift bricks, the Government did not act. Following a general election, the new Parliament and Labour-led Government started in June 2024. However, as of April 2025, the idea of mandating swift bricks remains as unlikely as it was, with the new government continuing the push for new developments and economic growth despite environmental costs. Despite these ongoing efforts, the three examples we selected give a good overview of the arguments raised and provide enough written material to study.

Discourse analysis

We analysed the discourse invoked in the debate on swift bricks by an activist-conservationist, the Government, and MPs. We analysed the contents and language of the petition and the broader Feather Speech campaign, the Government’s response, and the transcript of the debate in the House of Commons. Hannah Bourne-Taylor provided the transcript of the Feather Speech in her newest book43. We also studied the briefing note posted on her website42. All quotes from the parliamentary debate come from the official transcript89, and the recording of the debate can be found on the House of Commons website. Finally, we also read the House of Commons Library debate pack48, which summarises the petition, the related debate, and the Government’s response.

When reading these documents through the lens of multispecies justice, we sought statements that reflected how swifts and their representation and agency were viewed by the respective stakeholders28. For representation, we investigated how and by whom swifts were represented and how humans connected to swifts. We also looked for potential inequities in how different species were treated. For agency, we checked whether swifts were considered to have moral or political rights to space shared with humans, and whether enabling agency—space to live according to their own wishes or biology—was used in the debate. We also looked for ways that collaboration and cohabitation were envisaged for the potential duad of humans and swifts within a shared environment. We considered what arguments were indicated for or against mandating swift bricks and, ultimately, the broader protection of swifts. Finally, although the main focus of the petition and the debate was on swifts, they also referred to three other red-listed species in the UK facing sharp population declines: house martins, starlings and house sparrows. We examined how the stakeholders referred to these and other species.

Data availability

The data analysed in the current study are available at, respectively: Transcript of the Feather Speech: Bourne-Taylor, H. Nature Needs You: The Fight to Save Our Swifts. (Elliott & Thompson, London, 2025), pages 264–265: https://eandtbooks.com/books/nature-needs-you/. Transcript and explanation of the Government response: Rankl, F., Ares, E. & Sturge, G. Debate on E-Petition 626737 Relating to Swift Bricks. (House of Commons Library, London, 2023): https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cdp-2023-0126/. Transcript of the Parliamentary debate: https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2023-07-10/debates/203F1289-9D61-415A-9429-984EFBF599F5/NewHousingSwiftBricks.

References

Brondizio, E. S., Settele, J., Díaz, S. & Ngo, H. T. (eds) Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES Secretariat, 2019). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3831673

Fischer, J., Riechers, M., Loos, J., Martin-Lopez, B. & Temperton, V. M. Making the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration a social-ecological endeavour. Trends Ecol. Evol. 36, 20–28 (2021).

Pörtner, H.-O. et al. Overcoming the coupled climate and biodiversity crises and their societal impacts. Science 380, eabl4881 (2023).

Kronenberg, J. et al. Cities, planetary boundaries, and degrowth. Lancet Planet. Health 8, e234–e241 (2024).

Oke, C. et al. Cities should respond to the biodiversity extinction crisis. npj Urban Sustain. 1, 1–4 (2021).

Muradian, R. & Gómez-Baggethun, E. Beyond ecosystem services and nature’s contributions: Is it time to leave utilitarian environmentalism behind?. Ecol. Econ. 185, 107038 (2021).

Welden, E. A., Chausson, A. & Melanidis, M. S. Leveraging nature-based solutions for transformation: reconnecting people and nature. People Nat. 3, 966–977 (2021).

Beatley, T. The Bird-Friendly City (Island Press, 2020).

Kellert, S. R. Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design (Yale University Press, 2018).

Zhong, W., Schröder, T. & Bekkering, J. Biophilic design in architecture and its contributions to health, well-being, and sustainability: a critical review. Front. Archit. Res. 11, 114–141 (2022).

zu Ermgassen, S. O. S. E., Utamiputri, P., Bennun, L., Edwards, S. & Bull, J. W. The role of “No Net Loss” policies in conserving biodiversity threatened by the Global Infrastructure Boom. One Earth 1, 305–315 (2019).

Sonter, L. J. et al. Local conditions and policy design determine whether ecological compensation can achieve No Net Loss goals. Nat. Commun. 11, 2072 (2020).

McPhearson, T., Kabisch, N. & Frantzeskaki, N. (eds) Nature-Based Solutions for Cities (Edward Elgar, 2023).

Sarabi, S. et al. Renaturing cities: from utopias to contested realities and futures. Urban For. Urban Green. 86, 127999 (2023).

Kronenberg, J. From neoliberal urban green space production and consumption to urban greening as part of a degrowth agenda. Cities 159, 105739 (2025).

Maller, C. Re-orienting nature-based solutions with more-than-human thinking. Cities 113, 103155 (2021).

Mullenbach, L. E., Breyer, B., Cutts, B. B., Rivers, L. III & Larson, L. R. An antiracist, anticolonial agenda for urban greening and conservation. Conserv. Lett. 15, e12889 (2022).

Sheikh, H., Foth, M. & Mitchell, P. From legislation to obligation: Re-thinking smart urban governance for multispecies justice. Urban Gov. 3, 259–268 (2023).

Fieuw, W., Foth, M. & Caldwell, G. A. Towards a more-than-human approach to smart and sustainable urban development: designing for multispecies justice. Sustainability 14, 948 (2022).

Roudavski, S. Interspecies design. in Cambridge Companion to literature and the Anthropocene (ed. Parham, J.) 147–162 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Steele, W. Planning Wild Cities: Human–Nature Relationships in the Urban Age. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315688756 (Routledge, 2020).

Wallach, A. D. et al. Recognizing animal personhood in compassionate conservation. Conserv. Biol. 34, 1097–1106 (2020).

Houston, D., Hillier, J., MacCallum, D., Steele, W. & Byrne, J. Make kin, not cities! Multispecies entanglements and ‘becoming-world’ in planning theory. Plan. Theory 17, 190–212 (2018).

Metzger, J. A more-than-human approach to environmental planning. in The Routledge Companion to Environmental Planning (eds Davoudi, S., Cowell, R., White, I. & Blanco, H.) 190–199 (Routledge, 2019).

Metzger, J. & Hillier, J. Bugs in the smart city: a proposal for going upstream in human–mosquito co-becoming. in Designing More-than-Human Smart Cities: Beyond Sustainability, Towards Cohabitation (eds Heitlinger, S., Foth, M. & Clarke, R.) 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1093/9780191980060.003.0009 (Oxford University Press, 2024).

Rupprecht, C. D. D. et al. Multispecies sustainability. Glob. Sustain. 3, e34 (2020).

Celermajer, D. et al. Multispecies justice: theories, challenges, and a research agenda for environmental politics. Environ. Polit. 30, 119–140 (2021).

Raymond, C. M. et al. Applying multispecies justice in nature-based solutions and urban sustainability planning: tensions and prospects. npj Urban Sustain. 5, 2 (2025).

Bawaka Country et al. Co-becoming Bawaka: towards a relational understanding of place/space. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 40, 455–475 (2016).

Grabowski, Z. J., Wijsman, K., Tomateo, C. & McPhearson, T. How deep does justice go? Addressing ecological, indigenous, and infrastructural justice through nature-based solutions in New York City. Environ. Sci. Policy 138, 171–181 (2022).

Graham, M., Maloney, M. & Foth, M. A city of good ancestors: urban governance and design from a relationist ethos. in Designing More-than-Human Smart Cities: Beyond Sustainability, Towards Cohabitation (eds Heitlinger, S., Foth, M. & Clarke, R.) 239–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/9780191980060.003.0014 (Oxford University Press, 2024).

Franklin, A. The more-than-human city. Sociol. Rev. 65, 202–217 (2017).

McKiernan, S. & Instone, L. From pest to partner: rethinking the Australian White Ibis in the more-than-human city. Cult. Geogr. 23, 475–494 (2016).

Toncheva, S., Fletcher, R. & Turnhout, E. Convivial conservation from the bottom up: human-bear cohabitation in the Rodopi Mountains of Bulgaria. Conserv. Soc. 20, 124 (2022).

Parker, D., Soanes, K. & Roudavski, S. Learning with owls: human–wildlife coexistence as a guide for urban design. People and Nature 7, 1619–1638 (2025).

Hayward, T. Interspecies solidarity: care operated upon by justice. in Justice, Property and the Environment (eds Hayward, T. & O’Neill, J.) 67–84 (Routledge, 1997).

Healey, R. & Pepper, A. Interspecies justice: agency, self-determination, and assent. Philos. Stud. 178, 1223–1243 (2021).

Thiel, P. L. & Hallgren, H. Rights of nature as a prerequisite for sustainability. in Strongly Sustainable Societies: Organising Human Activities on a Hot and Full Earth (eds Bonnedahl, K. J. & Heikkurinen, P.) 61–76 (Routledge, 2019).

Putzer, A., Cook, J. & Pollock, B. Putting the rights of nature on the map. A quantitative analysis of rights of nature initiatives across the world—Second Edition. J. Maps 21, 2440376 (2025).

Nussbaum, M. C. Justice for Animals: Our Collective Responsibility (Simon & Schuster, 2023).

BTO. BirdFacts: Swift. https://www.bto.org/understanding-birds/birdfacts/swift (2025).

Bourne-Taylor, H. Petition 626737: Make Swift Bricks Compulsory in New Housing to Help Red-Listed Birds (Briefing Note). (2023).

Bourne-Taylor, H. Nature Needs You: The Fight to Save Our Swifts (Elliott & Thompson, 2025).

Foster, C. The Screaming Sky: In Pursuit of Swifts (Little Toller Books, 2021).

Bromhall, D. Devil Birds: The Life of the Swift (Hutchinson, 1980).

Gibson, S. Swifts and Us: The Life of the Bird That Sleeps in the Sky (William Collins, 2022).

Cocker, M. One Midsummer’s Day: Swifts and the Story of Life on Earth (Jonathan Cape, 2023).

Rankl, F., Ares, E. & Sturge, G. Debate on E-Petition 626737 Relating to Swift Bricks. (House of Commons Library, 2023).

Kronenberg, J., Andersson, E. & Tryjanowski, P. Connecting the social and the ecological in the focal species concept: case study of White Stork. Nat. Conserv. 22, 79–105 (2017).

Arcari, P., Probyn-Rapsey, F. & Singer, H. Where species don’t meet: Invisibilized animals, urban nature and city limits. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 4, 940–965 (2021).

Colléony, A., Clayton, S., Couvet, D., Saint Jalme, M. & Prévot, A.-C. Human preferences for species conservation: animal charisma trumps endangered status. Biol. Conserv. 206, 263–269 (2017).

Allen, B. Pigeon (Reaktion Books, 2009).

Jerolmack, C. The Global Pigeon (University of Chicago Press, 2013).

Petri, O. & Guida, M. (eds) Winged Worlds: Common Spaces of Avian-Human Lives (Routledge, 2023).

Holmes, M. Bird boxes and sparrow traps: the technological regulation of avian life in the United States. Technol. Cult. 65, 819–842 (2024).

Plumwood, V. Nature in the active voice. Aust. Humanit. Rev. 46, 111–127 (2009).

Van Horn, G., Kimmerer, R. W. & Hausdorfer, J. (eds) Partners Vol. 3 (Center for Humans and Nature Press, 2021).

Roudavski, S. The ladder of more-than-human participation: a framework for inclusive design. Cult. Sci. 14, 110–119 (2022).

Parker, D., Roudavski, S., Isaac, B. & Bradsworth, N. Toward interspecies art and design: prosthetic habitat-structures in human-owl cultures. Leonardo 55, 351–356 (2022).

O’Brien, K. et al. IPBES Transformative Change Assessment: summary for policymakers. https://zenodo.org/records/14513975, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14513975 (2024).

Pascual, U. et al. Diverse values of nature for sustainability. Nature 620, 813–823 (2023).

O’Connor, S. & Kenter, J. O. Making intrinsic values work; integrating intrinsic values of the more-than-human world through the Life Framework of Values. Sustain. Sci. 14, 1247–1265 (2019).

Willemen, L., Kenter, J. O., O’Connor, S. & van Noordwijk, M. Nature living in, from, with, and as people: exploring a mirrored use of the Life Framework of Values. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 63, 101317 (2023).

Dominiak-Szymańska, P., Łaszkiewicz, E. & Kronenberg, J. Children’s participation in green space planning: a pathway to environmental justice. Child. Geogr. 22, 944–964 (2024).

McFadden, E. & Downie, K. Overcoming the tokenization of people with disabilities in community development. in Community Development and Public Administration Theory (eds Nickels, A. E. & Rivera, J. D.) 191–208 (Routledge, 2018).

Stone, C. D. Should trees have standing—toward legal rights for natural objects. South. Calif. Law Rev. 45, 450–501 (1972).

Heitlinger, S., Foth, M. & Clarke, R. (eds) Designing More-than-Human Smart Cities: Beyond Sustainability, Towards Cohabitation (Oxford University Press, 2024).

Tănăsescu, M. Representation, democracy, and the ecological age. Quad. Filos. 10, 121–132 (2023).

Sheikh, H., Mitchell, P. & Foth, M. Reparative futures of smart urban governance: a speculative design approach for multispecies justice. Futures 154, 103266 (2023).

Tomitsch, M., Fredericks, J., Vo, D., Frawley, J. & Foth, M. Non-human personas. Including nature in the participatory design of smart cities. Interact. Des. Archit. 50, 102–130 (2021).

d’Hoop, A. Crossing worlds in buildings: caring for swifts in Brussels. Humanimalia 14, 43–82 (2023).

Knight-Lenihan, S. Achieving biodiversity net gain in a neoliberal economy: the case of England. Ambio 49, 2052–2060 (2020).

Marshall, C. A. M. et al. England’s statutory biodiversity metric enhances plant, but not bird nor butterfly, biodiversity. J. Appl. Ecol. 61, 1918–1931 (2024).

Apostolopoulou, E. & Adams, W. M. Biodiversity offsetting and conservation: reframing nature to save it. Oryx 51, 23–31 (2017).

zu Ermgassen, S. O. S. E. et al. The ecological outcomes of biodiversity offsets under “no net loss” policies: a global review. Conserv. Lett. 12, e12664 (2019).

Lindenmayer, D. B. et al. The anatomy of a failed offset. Biol. Conserv. 210, 286–292 (2017).

Chapman, K., Tait, M. & Postlethwaite, S. Are Housing Developers Delivering Their Ecological Commitments? (Wild Justice, 2024).

Wolch, J. Green urban worlds. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 97, 373–384 (2007).

Ávila, M. Designing for Interdependence: A Poetics of Relating (Bloomsbury, 2022).

Lemes de Oliveira, F. Nature in nature-based solutions in urban planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 256, 105282 (2025).

Pineda-Pinto, M., Frantzeskaki, N. & Nygaard, C. A. The potential of nature-based solutions to deliver ecologically just cities: lessons for research and urban planning from a systematic literature review. Ambio 51, 167–182 (2022).

Ferri, M. Ancient artificial nests to attract swifts, sparrows and starlings to exploit them as food. in Birds as Food: Anthropological and Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives (eds Duhart, F. & Macbeth, H.) 217–239 (International Commission on the Anthropology of Food and Nutrition, 2018).

Randrup, T. B., Buijs, A., Konijnendijk, C. C. & Wild, T. Moving beyond the nature-based solutions discourse: introducing nature-based thinking. Urban Ecosyst. 23, 919–926 (2020).

Thomsen, B. et al. Reimagining entrepreneurship in the Anthropocene through a multispecies relations approach. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 22, e00507 (2024).

Chan, K. M. A. et al. The multiple values of nature show the lack of a coherent theory of value—in any context. People Nat. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.70039 (2025).

Day, J., Mayer, E. & Newell, D. The Swift—A Bird You Need to Help! Bull. Chart. Inst. Ecol. Environ. Manag. 104, 38–42 (2019).

Williams, C., Murphy, B. & Gunnell, K. Designing for Biodiversity: A Technical Guide for New and Existing Buildings (RIBA Publishing, 2013).

BSI. BS 42021:2022 Integral Nest Boxes. Selection and Installation for New Developments. Specification. (British Standards Institution, 2023).

UK Parliament. New Housing: Swift Bricks (Volume 736: Debated on Monday 10 July 2023 in the House of Commons). (UK Parliament, 2023).

Acknowledgements

This research has been funded by the National Science Centre, Poland, with grant number 2023/49/B/HS4/01926 (BirdEcon). The funder played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Stockholm University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.K. and E.A. conceived the idea; J.K. carried out the analysis and wrote the initial draft; E.A. and C.R. reviewed the manuscript; all authors revised the draft and wrote the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kronenberg, J., Andersson, E. & Sandbrook, C. If a swift could fight for their existence with words: nonhuman interests and politics. npj Urban Sustain 5, 70 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-025-00263-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-025-00263-3

This article is cited by

-

Respecting nature’s limits in urban planning: values and principles for human–nature partnerships

npj Urban Sustainability (2026)