Abstract

Phononic crystals and acoustic metamaterials are expected to become an important enabling technology for science and industry. Currently, various experimental methods are used for evaluation of acoustic meta-structures, such as impedance tubes and anechoic chambers. Here we present a method for the precise characterization of acoustic meta-structures that utilizes rapid broadband acoustic pulses generated by point-like and effectively massless laser plasma sound sources. The method allows for broadband frequency response and directivity evaluations of meta-structures with arbitrary geometries in multiple sound propagation axes while also enabling acoustic excitation inside the structure. Experimental results are presented from acoustic evaluations of various phononic crystals with band gaps in the audible range, notably also in the very low frequencies, validating the predictions of numerical models with high accuracy. The proposed method is expected to boost research and commercial adoption of acoustic metamaterials in the near future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nature offers various physical materials that allow for acoustic wave manipulation, i.e., reflection, absorption, refraction, diffraction, and diffusion. The solution to the quantum mechanical wave equation in crystalline materials, which revealed the existence of electronic band gaps1,2, inspired the design of artificial periodic structures with extraordinary properties regarding their interaction with classical electromagnetic, mechanical and acoustic waves3,4,5. Such structures can be broadly divided in Phononic Crystals (PCs), which exploit Bragg diffraction to form phononic band gaps6,7, and Acoustic Metamaterials (AMMs), which rely on locally resonant structures8,9,10 to achieve extraordinary wave manipulation capabilities. Due to their remarkable acoustic properties, PCs and AMMs, simply termed thereafter AMMs, already find application in various technological fields with broad commercial potential11,12, such as room acoustics and noise insulation13,14,15 but also in radical acoustic innovations, e.g., the development of acoustic super-lenses, low-frequency reflectors, acoustic cloaks and particle manipulators16,17,18,19,20,21. Additionally, AMMs have been used to create acoustic wave decelerators and acoustic traps for quantum sensing and computation22,23,24,25,26,27. The field of AMMs is dynamic and expansive with new applications continuously appearing.

AMM design and development is based on established mathematical and computational tools. Their experimental evaluation relies on various methods, mainly the use of Impedance Tubes (ITs) and conventional loudspeakers. Single- or few-cell AMM acoustic transmission assessment is typically achieved with the use of ITs28. While ITs provide a low noise measurement environment, they impose restrictions on the structure’s geometry, as the sample needs to be cylindrical or cubic with specific dimensions to fit in the tube. Also, assessment of AMMs in different sound propagation axes requires a different sample for each axis. The acoustic excitation in ITs is bound to be at a specific position outside the structure, while their frequency range of operation is often limited, commonly in the range up to ~7 kHz. Apart from these technical limitations, ITs are relatively costly. Furthermore, conventional loudspeakers work well for large AMM arrangements within a specific frequency range but are unsuitable for the evaluation of smaller structures such as unit cells, due to increased diffraction interference caused by the large size of the source. Importantly, specialized and costly infrastructure is usually required for the evaluations, particularly anechoic chambers or connected rooms. Excitation inside the AMM sample via conventional loudspeakers is nearly impossible, except for the high audible frequencies or ultrasounds, which can be achieved by piezoelectric transducers. However, this entails interventions to the material with potentially detrimental results29. Lastly, the frequency-dependent directivity of conventional electromechanical and piezoelectric transducers hinders the evaluation in different sound propagation directions.

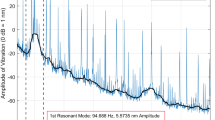

The proposed method based on Laser Plasma Sound Sources (LPSSs) offers distinct advantages over these traditional methods. LPSSs are generated in ambient air or other gaseous or liquid media by the thermoelastic reaction following Laser-Induced Breakdown (LIB), while in solids they are formed due to the pressure induced in the surrounding medium by Laser Ablation (LA). For ionization of the ambient air by nanosecond lasers, the interaction of high intensity laser pulses \(( > {10}^{12}{{{{{\rm{W}}}}}}{{{{{{\rm{cm}}}}}}}^{-2})\) with the air molecules leads to the generation of high temperature free electrons, initially via multiphoton ionization and then via an electron-electron avalanche driven by inverse Bremsstrahlung. Electron generation phenomena take place in the timescale of the laser pulse, i.e. within 10–20 ns. The hot free electrons interact with the initially cold heavy particles, namely ions, atoms and molecules within the excited volume via Bremsstrahlung, electron-ion recombinations and electron de-excitations, causing the heavy particles to thermalize within a few microseconds30. Simultaneously, LPSSs emit light due to these luminescent and thermal processes31. The heated air volume undergoes thermal expansion, which leads to the formation of a positive pressure, while consequent elastic reaction of the medium leads to the formation of a negative pressure. Hence, the LPSS pressure profile takes the form of an acoustic N-pulse, which can have varying durations that range from a few microseconds (or even sub-microsecond for femtosecond laser pulses) up to hundreds of microseconds depending on the laser pulse characteristics. A typical N-pulse signature in the time and frequency domain is shown in Fig. 1. N-pulses exhibit a 1st order high-pass profile in the lower end of the acoustic frequency spectrum, which for nanosecond laser excitation extends from the infrasounds (<20 Hz) to the high audible frequencies (~20 kHz) or the near ultrasounds (<60 kHz), while for femtosecond laser excitation it can extend to the mid-ultrasounds (up to ~500 kHz)32. Peak pressure levels can be extremely high (>130 dB) depending on the total deposited optical energy. Comprehensive studies can be found in refs. 33,34,35,36,37, while the relation to the laser radiation characteristics is analyzed in refs. 32,36,38,39.

Furthermore, the acoustic directivity of LPSSs ranges from omnidirectional to strongly directional, depending on the plasma geometry. Tightly focused nanosecond pulses generate point-like plasma sources with sub-millimeter dimensions and omnidirectional acoustic emission40,41. Loosely focused picosecond or femtosecond laser pulses generate line-like sources, typically with sub-millimeter thicknesses and lengths spanning from a few millimeters to hundreds of meters, depending on the laser pulse energy and focusing conditions. Such sources are referred to as laser-plasma filaments42,43 and produce cylindrical acoustic waves with well-known directional and propagation properties44,45. More information regarding the LPSS acoustic directivity can be found in the Methods section.

The massless and point- or line-like geometry of LPSSs, along with their repeatable and broad frequency spectrum and rapid pressure profile render them suitable for a wide range of applications. LPSSs are used in Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS)46, non-destructive testing47 material diagnostics48 and in military applications49, while their suitability for room acoustic measurements has also been proposed37. Recently, controlled and continuous sound reproduction via LPSSs has been experimentally demonstrated50,51,52. Following, experimental results are presented from the acoustic transmission evaluation of PCs with varying geometrical and acoustic characteristics, clearly revealing the expected acoustic band gaps and passband zones formed by Bragg diffraction. Significantly, the method allows for the identification of very low frequency band gaps starting from the infrasounds and extending to the few kHz range. These findings validate the numerical calculations within an extended frequency range with high accuracy, surpassing the capabilities of current AMM evaluation methods. Therefore, we demonstrate that LPSSs constitute a near-ideal tool for PC and AMM testing, acoustic evaluation and characterization.

Results

The method’s effectiveness is demonstrated here by using three PC structures: a 3-cell cylinder with identical unit cells, a 3-cell cylinder with a defective middle cell and a 3 × 3 × 3-cell cube. The structures consist of a network of spherical cavities connected by cylindrical conduits, formed by repetition of the unit cell shown in Fig. 2a. The real samples and the related computational models are shown in Fig. 2b, c, while a schematic diagram of the laser excitation process is shown in Fig. 2d. For the cylinders, additional measurements with closed peripheral holes are presented for comparison to IT measurements, which are unavoidably carried out with closed holes. The cylinder is acoustically excited both outside the structure and inside the first unit cell, while the cube is always excited in the central unit cell. These cases are presented below. The LPSSs are generated by 6 ns, 532 nm laser pulses with ~120 mJ energy (see Methods section).

a Unit cell design process from the air domain into the cubic and then to the cylindrical cell. The lattice constant is \(a=29{{{{{\rm{mm}}}}}}\), the sphere radius is \(R=0.395a\) and the radius of the air conduits is \(r=0.095a\). b 3-cell cylinder and models of the normal and defective samples. Total length and radius of the samples are 87 mm and 29 mm, respectively. c 3 × 3 × 3-cell cubic sample with 87 mm side length and respective model showing the three sound propagation axes ΓΧ, ΓΜ, ΓR. d Schematic diagram of the LPSS excitation of the structures for the various evaluation scenarios.

Normal cylinder, closed holes, source outside

Figure 3 shows the time-domain profile of the acoustic signal transmitted through the cylinder, measured at the output hole. It becomes apparent that the propagation of the N-pulse inside the PC results to multiple oscillations of the acoustic pressure and a total increase of its duration from ~50 μs to a few milliseconds. Such broadening is the result of acoustic filtering; however, it is difficult to deduce more precise acoustic characteristics from the time domain signals. For this reason, the following analysis focuses on the frequency spectra of the transmitted signals obtained via Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT). Figure 4a shows the simulated and measured acoustic transmission spectrum of the normal cylinder in the audible frequency range. It is apparent that the LPSS measurement captures the acoustic features with high accuracy. Three phononic band gaps are clearly observed at 2–9.5 kHz, 11–13 kHz and 15–19 kHz with 30–40 dB depth, separated by passbands with characteristic resonant triplets.

Acoustic band gaps and passband resonant features predicted by the simulations are clearly observed in the measurements. Evaluations are carried out across the entire audible range (20 Hz–20 kHz), simulation (red dashed line), LPSS measurement (black solid line), IT measurement (green dotted line). a Normal structure with closed holes, source outside. b Defective structure with closed holes, source outside. c Normal structure with open holes, source outside and d multiple measurements of the same structure taken at different times, showing the excellent repeatability of the characterization method. e Normal structure with open holes, source inside. Measurements taken with LPSSs generated by 6 ns, 532 nm, 120 mJ pulses.

A mismatch of ~100 Hz between measurements and simulations in some resonant frequencies can be attributed to small deviations in the structure’s geometry from the simulated model. This is confirmed by computational evaluations showing that a 500 μm divergence in the air conduit diameter leads to >100 Hz deviation in the resonant frequencies. While the measurement noise floor occasionally appears above the band gap floor e.g., around 6–9 kHz, this problem can be mitigated by reducing the noise in the measurement environment. The method demonstrates clear superiority over the IT measurement, which is evident in the explicitly higher detail of the captured spectral features across the entire audible spectrum. These findings are in agreement with the computational evaluations of the band structure for this PC shown in Fig. 5a, where the gray zones denote the phononic band gaps. A sound hard boundary (solid) condition is used for modeling the closed peripheral holes, as described in detail in the Methods section. It can be seen that the measured band gaps shown in Fig. 4a, are in excellent agreement with the ones calculated in the band structure.

a With closed peripheral holes (sound hard boundary) and b with open peripheral holes (sound soft boundary). Periodic arrangement of the unit cell along the ΓΧ direction. The radius of the spherical cavity of the unit cell is \(R=0.395\alpha\) and the radius of the cylindrical conduit is \(r=0.095\alpha\).

Defective cylinder, closed holes, source outside

The impact of introducing a defective cell in the structure can be seen in Fig. 4b. The third peak of the first resonance triplet is now shifted from 1.9 kHz to 2.3 kHz while the first peak of the second resonant triple is shifted from 10 kHz to 9.1 kHz. This is due to energy localization in the defective cell resulting to strong resonances lying in the first band gap (see Discussion). Another resonance peak appears within the second band gap at 13 kHz, while the spectrum from 15 kHz and beyond remains unchanged. These acoustic features are clearly captured by the LPSS measurements while the IT measurement fails to imprint the characteristic acoustic features even within its limited frequency range. Figure 6 shows the calculated pressure color maps at the frequencies of the three resonant peaks. It is interesting to note that calculation of the Helmholtz resonance for a geometry with the spherical cavity of the defective cell and a neck double that of the cylindrical air conduit, as is the case for two connected spheres, gives a fundamental resonance frequency of 2.3 kHz and a fourth harmonic of 9.1 kHz.

The resonant frequency of each mode is 2.3 kHz a, 9.1 kHz b, and 13.0 kHz c, as shown in each part of the figure. In d, the modeled middle cross section of the specimen is presented (also shown in Fig. 2b).

Normal cylinder, open holes, source outside

In Fig. 4c the measured and simulated acoustic transmission of the cylinder is shown, this time with the peripheral holes open, while Fig. 4d presents four different measurements executed at different times, demonstrating the repeatability and robustness of the method. An excellent match with the simulation is demonstrated for this measurement, which is not feasible via the IT due to the open holes. Opening the peripheral holes leads to a change in the structure’s acoustic behavior, especially in the upper and lower frequency range. Particularly, the first resonance triplet is now replaced by a pass band between 2.9 kHz and 3.5 kHz, shifting the lower edge of the first band gap from 2 kHz to 3.5 kHz. This shift reveals the existence of an extended band gap below the first passband that goes down to the infrasounds, which is related to the periodically arranged soft scatterers emerging by opening the peripheral holes53,54. Moreover, the appearance of the passband with the fivefold resonant feature predicted by the simulation between 14 kHz and 19 kHz is validated by the measurement. Finally, the transmission spectrum between 3 kHz and 13 kHz remains unchanged compared to the closed holes scenario. Again, the findings agree with the computational evaluations of the band structure of this PC, shown in Fig. 5b. As analyzed in the Methods section, the boundary condition at the peripheral holes of the sample are changed from sound hard to sound soft (air) to model the open holes. The results accurately predict the measured and the calculated band gaps shown in the transmission spectrum of Fig. 4c. As observed from the experimental measurements, by opening the peripheral holes, a band gap is formed at a very low frequency range from the infrasounds up to 2.9 kHz. According to previous works53,54, the direct connection of the incident pressure wave to the external air through the peripheral holes results in significant suppression of the pressure at the position of the peripheral holes, leading to backward reflection of the wave. This leads to the elimination of any passbands in the frequency range up to 2.9 kHz and to the appearance of the low frequency gap (see Methods section for further details). It Can be seen that the first passband of the band structure (2.9–3.7 kHz), matches the passband measured in the experiments (Fig. 4c, e).

Normal cylinder, open holes, source inside the first cell

Finally, the cylinder’s response to excitation inside the first cell is shown in Fig. 4e. A small deviation of 200–300 Hz in the passband triplet between 9 kHz and 11 kHz as well as a spectral magnitude mismatch of the order of 10 dB in the high frequencies (15–17 kHz) can be attributed to slight deviations in the positioning of the source inside the sphere. It is stressed that such a measurement is exclusively enabled by LPSSs. The predicted band gap from the infrasounds to \(\sim 3.5{{{{{\rm{kHz}}}}}}\) is again validated by the measurement.

Cube

Here, the standard evaluation methodology along three sound propagation axes is followed, in which the LPSS is generated on point Γ while the measurements are carried out along the directions ΓΧ, ΓΜ and ΓR (see Fig. 2c). The measurements allow for evaluation of the structure’s transmission directivity, which is crucial for applications such as sound steering, focusing and acoustic filtering in 3D space. The microphone is placed on the surface of a virtual sphere with \(R=12{{{{{\rm{cm}}}}}}\) around the cube to ensure equal observation distance for all three measurements. Figure 7a–c show the simulated and measured transmission spectra along the axes ΓΧ, ΓΜ and ΓR, while Fig. 7d presents the measured spectra for the three directions. Again, it becomes evident that the LPSS measurements capture the main features of the predicted acoustic transmission in detail. In all three propagation directions, a resonant feature with four peaks can be observed in the lower frequencies (1–3.5 kHz), followed by a phononic band gap extending up to 9.5 kHz. A second band gap between 11 kHz and 15 kHz is also apparent in all three axes, separated from the first band gap by a passband resonant feature ranging from 9.5 kHz to 11 kHz.

When excited in the center, the cube acts as a 3-dimensional acoustic filter with near-homogeneous response along the different propagation axes. Evaluation across the entire audible frequency range (20 Hz–20 kHz) enabled by the LPSS method. Simulated (red dashed line) and measured (black solid line) transmission spectra along the a ΓX, b ΓΜ, c ΓR directions. d Comparative plot of measured responses in the three directions. Measurements taken with LPSSs generated by 6 ns, 532 nm, 120 mJ pulses.

It becomes apparent that the cubic structure exhibits a near-homogeneous transmission spectrum in all propagation directions, effectively acting as a 3-dimensional spatial acoustic filter, a result that could be experimentally validated only via the proposed method. Also, acoustic evaluation of the cubic structure via the IT is impossible due to the previously described geometrical limitations.

Note that, in contrast to the response of the cylinder, where the hole at the observation side has the main contribution, the cube’s response is influenced by multiple holes.

The computationally evaluated band structure by periodic arrangement of the unit cell along all directions is presented for the audible spectrum in Fig. 8a. Two complete band gaps, the first from 3.7 kHz to 9.4 kHz and the second from 10.7 kHz to 13.1 kHz are denoted with gray. A third gap appears along the ΓΧ direction between 16.7 kHz and 19.0 kHz, while for the same direction the lower boundary of the first band gap is reduced to 2 kHz. These theoretical and computational predictions are here experimentally validated for the first time with high accuracy within the entire audible frequency range. It becomes apparent that the evaluation of the cubic structure in the ΓΧ, ΓΜ and ΓR directions constitutes a direct measurement of the calculated band structure, exclusively enabled by the use of LPSSs, generated at point Γ of the Brillouin zone.

As a final remark, the experiments and simulations showed that all evaluated structures exhibit two band gaps with central frequencies ~6 kHz and 12 kHz. Evaluation of the Bragg condition for the PC lattice constant \(\alpha =29{{{{{\rm{mm}}}}}}\) and for a longitudinal speed of sound \(v=343{{{{{\rm{m}}}}}}{{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}}^{-1}\) predicts the emergence of a first band gap at \({f}_{{{{{{\rm{gap}}}}}}}=5.9{{{{{\rm{kHz}}}}}}\) and a second band gap at the second harmonic \(2{f}_{{{{{{\rm{gap}}}}}}}=11.8{{{{{\rm{kHz}}}}}}\). The band gap limits are related to the geometric characteristics of the spherical and cylindrical volumes, as described in ref. 28.

Discussion

The experimental results showed that the proposed LPSS method for the acoustic evaluation of PCs and AMMs provides reliable information regarding the entire band structure over a wide frequency range, accounting also for 3D acoustic propagation effects. It also enables the accurate validation of the computational predictions for all different structures and source positionings. Modifications of the structure’s acoustic properties e.g., by closing the peripheral holes or by introducing a defective cell, are clearly captured in the measured transmission spectra. Moreover, LPSS measurements allow for averaging over a large number of acoustic responses within a short time and for windowing around the averaged acoustic response (see Methods), significantly mitigating the impact of ambient noise and reflections, hence relaxing the requirements for ideal acoustic testing conditions. The effectiveness of denoising via signal post-processing becomes apparent by considering that the presented experiments were carried out in a non-specialized laser laboratory environment. Moreover, the use of stronger laser pulses e.g., up to 500 mJ which are nowadays delivered by typical and relatively inexpensive nanosecond laser systems, would further reduce the impact of noise in non-specialized environments.

Regarding the measurement’s frequency bandwidth, LPSSs generated by nanosecond laser pulses can be used for evaluations from the very low frequencies up to the near ultrasounds. i.e., up to several tens of kHz32. These measurement characteristics allow for precise evaluation of the low frequency acoustic band gaps extending from the infrasounds to the few kHz, depending on the structure. Such a range is not possible to be covered via a single conventional transducer while it also extends beyond the typical frequency range achieved by the standardized IT methods. It should be noted that the results presented here are restricted to 20 kHz for presentation reasons and not due to inherent limitations of the measurement method.

Moreover, given that LPSSs generated by femtosecond excitation have a 1st order high-pass frequency profile up to hundreds of kHz, acoustic evaluations can be achieved up to the mid ultrasound range. Also, the massless and spatially unbound nature of the LPSSs enables localized excitation inside the acoustic structure, which is compromised by use of conventional transducers. To the best of our knowledge, the relevant presented results go beyond the capabilities of any current state-of-the-art method. Excitation inside the structure is crucial for the design, development and exploitation of spatial filters for 3D sound manipulation in various applications, e.g., laser-based sound reproduction and transmission, medical applications, sensing, sound trapping and other. Finally, the proposed method can also be used for the evaluation of conventional acoustic materials.

Conclusions

In this work, we presented findings demonstrating that laser plasma sound sources constitute a near-ideal tool for the evaluation and characterization of phononic crystals and acoustic metamaterials. LPSSs can constitute a favorable alternative to the conventional evaluation methods and significantly enhance the credibility, generality and efficiency of the acoustic characterization procedure. The widespread adoption of the method is anticipated to facilitate the development of acoustic metamaterials and their utilization in scientific and commercial settings. Here, experimental measurements of the transmission spectra of various PC samples were analyzed, demonstrating the method’s capability to capture the acoustic features of the structures with high accuracy. The experimental findings allowed for validation of the adopted numerical models across the complete audible range, which was not possible with the currently available experimental methods. The omnidirectional emission of LPSSs enabled acoustic transmission evaluation of structures in multiple directions using a single sample. Finally, it was shown that the massless and spatially unbound nature of LPSSs allows for characterization and exploitation of acoustic meta-structures by localized internal acoustic excitation, e.g., for the development and evaluation of 3D spatial acoustic filters and acoustic cavities used as sound traps and sensors.

Methods

Simulations

All numerical simulations were performed using the Acoustics Module together with the Solid Mechanics interface of COMSOL Multiphysics® (version 5.5). The Finite Element Method included in the commercial package was utilized to numerically solve the equation for propagation of sound waves:

where \(p\) is the total acoustic pressure, \(\rho\) is the density of ambient air, \(\omega =2\pi f\) is the angular frequency, \(f\) is the frequency, \(c\) is the speed of sound, and the wavenumber is \(k=\omega /c\). The following values for the properties of the PLA were used in the numerical calculations: Young’s Modulus \(E=3.5{{{{{\rm{GPa}}}}}}\), Poisson ratio \(v=0.35\), and density \(\rho =1240{{{{{\rm{kg}}}}}}{{{{{{\rm{m}}}}}}}^{-3}\). The acoustic-solid interaction, frequency domain interface was used in the model for the coupling of the air and the solid boundary. A monopole point source of flow type was used to represent the laser-plasma sound source within the audible frequency range. Perfectly Matched Layers (PML) were used at the boundaries of the computational domain to eliminate boundary reflections. The transmission spectra were calculated according to:

where \({p}_{{{{{{\rm{T}}}}}}}\) and \({p}_{{{{{{\rm{I}}}}}}}\) represent the transmitted and incident pressure field on the two sides of the specimen. A free tetrahedral element mesh was adopted with a minimum element size of \(0.05{{{{{\rm{mm}}}}}}\) and a maximum element growth rate of 1.45. The band structure of the 3D structure (Fig. 8) was calculated by using Bloch-Floquet periodic boundary conditions on the sides of a single unit cell. For the band structure calculations of the cylindrical samples along the ΓΧ direction (Fig. 5), sound hard and sound soft boundaries were used to model the closed and open peripheral holes, respectively. Sound hard boundaries impose zero acceleration on the normal component of the fluid (air) at the position of the holes, which describes the case where the holes are blocked and do not directly communicate with the ambient air. For the case of open holes where there is a direct connection between the air conduits of the structure and the ambient air, it is known that the pressure at the position of the holes goes to zero53,54. This results to strong reflection of the propagating pressure wave in the low frequencies, which is known to lead to the formation of a low-frequency stopband, as the one observed in the experiments of the cylindrical structure with open holes. As know from previous works53,54, such a scenario is precisely modeled by sound soft boundaries, which impose zero pressure at the position of the holes. Finally, along the X direction Bloch-Floquet periodic boundary conditions were used.

LPSS characterization

The LPSSs are characterized here by means of acoustic directivity measurements. The microphone is placed at 0, 30, 60 and 90 deg. azimuthal angles with respect to the laser beam propagation direction and at constant distances 12 and 60 cm from the plasma, as shown in Fig. 9a. The polar diagrams of Fig. 9b, c are calculated by taking the total acoustic energy of the measured N-pulses, while the emission towards the directions from 120 to 180 degrees are mirrored considering cylindrical symmetry. The source at 12 cm exhibits a maximum 4 dB deviation between 0 and 90 degrees, while no deviation is observed at 60 cm.

Moreover, non-linear effects are not considered here since as known from previous studies39, but also from test measurements carried out by the authors, the initial shock wave generated by the LPSS under the specific experimental conditions quickly transforms into a linear soundwave, after propagating less than 1 cm away from the plasma source. Finally, the sound pressure level of a single N-pulse was measured ~97 dB at 1 m distance from the plasma for a 35 ms measurement window (impulse measurement), which approximately corresponds to 130 dB peak pressure of the N-pulse.

Experiments

The samples used in this study were manufactured with polylactic acid (PLA) by the fused filament fabrication technique on an XYZ-Printing “daVinci Super” 3D printer. In the experiments, the laser pulses are focused by a 10 cm lens. A laser pulse repetition rate of 5 Hz is used, allowing for a 200 ms time distance between consecutive pulses. The individual acoustic N-pulses have a duration of ~70 μs while the duration of the acoustic responses of the probed structures is of the order of 5 ms. The plasma sources are placed at the center of the spherical volumes via a camera that monitors the plasma. The acoustic measurement system is based on a broad frequency range (90 kHz) and high dynamic range (35 dB(A)–160 dB) microphone (G.R.A.S 46BE and power module 12AK). The signals are sampled by a broad frequency range (92 kHz) sound card (RME Fireface 802) at 192 kHz sampling rate and 24-bit resolution.

Finally, the impedance tube (IT) measurements were carried out with the transmission loss tube kit 4206-T by Brüel & Kjær, according to ASTM E2611-09 standards55. The small tube set-up 4206-T was used with a diameter of 29 mm and a bandwidth from 0.5 to 6.4 kHz. The transfer matrix method was applied for the calculation of the sound transmission loss where the elements of the matrix were measured through the four-microphone configuration and the two-load method according to its standards55. The experimental procedure was controlled through PULSE LabShop version 18.1 by Brüel & Kjær and LAN-XI Type 3160-A-042 input/output module.

Signal analysis

Each measurement \({y}_{m}\left(\tau \right)\) has a total duration of \({T}_{{{{{{\rm{tot}}}}}}}=60{{{{{\rm{s}}}}}}\) and contains a train of \({\rm N}=300\) responses. The captured responses are separated into 300 distinct signals:

each containing one single response. The chunks are averaged to suppress the ambient noise, so that:

Finally, the averaged signal \({y}_{m,{{{{{\rm{avg}}}}}}}\left(\tau \right)\) is windowed using a Tukey window \({w}_{{{{{{\rm{T}}}}}}}\left(\tau \right)\) of 7 ms width placed around each response, to further suppress ambient noise and to eliminate potential reflections from surrounding surfaces. Hence, the final time-domain signal can be written as:

From \(y\left(\tau \right)\) the acoustic frequency response of the structure to N-pulse excitation is derived by DFT:

where \({\rm T}=38000\) is the number of samples contained in a chunk. The spectrum \(Y\left(k\right)\) is the acoustic response to the laser-plasma sound source, which has a 1st-order high-pass profile in the frequency range of interest. To remove this high-pass profile from the measurement and obtain the equalized transmission spectrum of the material, a 1st-order low-pass filter is applied on \(Y\left(k\right)\), so that the material’s normalized frequency response is given by:

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The data are locally stored by the authors and are in .wav and .csv format for the experiments and simulations, respectively.

Code availability

Codes generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Brillouin, L. Wave propagation in periodic structures, 2nd ed. (Dover Publ., 1953).

Sigalas, M., Papacinstantopoulos, A. D. & Bacalis, C. N. Total energy and band structure of the 3d,4d, and 5d metals. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter. 45, 5779 (1992).

Ho, M. K., Chan, T. C. & Soukoulis, M. C. Existence of a Photonic Gap in Periodic Dielectric Structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 3152 (1990).

Sigalas, M. & Economou, E. N. Band structure of elastic waves in two dimensional systems. Solid State Commun. 86, 141–143 (1993).

Herraiz-Martinez, F. J. et al. Self-Diplexed Patch Antennas Based on Metamaterials for Active RFID Systems. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 57, 1330–1340 (2009).

Hussein, M. I., Leamy, M. J. & Ruzzene, M. Dynamics of Phononic Materials and Structures: Historical Origins, Recent Progress, and Future Outlook. ASME. Appl. Mech. Rev. 66, 040802 (2014).

Yablonovitch, E. & Gmitter, J. T. Photonic band structure: The face-centered-cubic case. Phys. Rev. Lett. 63, 1950–1953 (1989).

Oudich, M., Gerard, N. J., Deng, Y. & Jing, Y. Tailoring Structure-Borne Sound through Bandgap Engineering in Phononic Crystals and Metamaterials: A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2206309 (2023).

Zhengyou, L. et al. Locally Resonant Sonic Materials. Sci. 289, 1734–1736 (2000).

Guancong, M. A. & Ping, S. Acoustic metamaterials: From local resonances to broad horizons. Sci. Adv. 2, 1501595 (2016).

Cummer, S., Christensen, J. & Alù, A. Controlling sound with acoustic metamaterials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16001 (2016).

Kadic, M. et al. 3D metamaterials. Nat Rev Phys 1, 198–210 (2019).

Mei, J. et al. Dark acoustic metamaterials as super absorbers for low-frequency sound. Nat. Commun. 3, 756 (2012).

Singh, S. K., Prakash, O. & Bhattacharya, S. Hybrid fractal acoustic metamaterials for low-frequency sound absorber based on cross mixed micro-perforated panel mounted over the fractals structure cavity. Sci. Rep. 12, 20444 (2022).

Yang, M. & Ping, S. Acoustic metamaterial absorbers: The path to commercialization. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 260504 (2023).

Popa, B. I. & Cummer, S. Negative refraction of sound. Nat. Mater. 14, 363–364 (2015).

Song, G. et al. Broadband Focusing Acoustic Lens Based on Fractal Metamaterials. Sci. Rep. 6, 35929 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. Three-dimensional Ultrathin Planar Lenses by Acoustic Metamaterials. Sci. Rep. 4, 6830 (2014).

Cheng, Y. et al. Ultra-sparse metasurface for high reflection of low-frequency sound based on artificial Mie resonances. Nat. Mater. 14, 1013–1019 (2015).

Zigoneanu, L., Popa, B. I. & Cummer, S. Three-dimensional broadband omnidirectional acoustic ground cloak. Nat. Mater. 13, 352–355 (2014).

Xu, J. et al. Acoustic metamaterials-driven transdermal drug delivery for rapid and on-demand management of acute disease. Nat. Commun. 14, 869 (2023).

Liu, Z. Trapping sound at corners. Nat. Mater. 18, 98–99 (2019).

Zhu, X. et al. Implementation of dispersion-free slow acoustic wave propagation and phase engineering with helical-structured metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 7, 11731 (2016).

Ba, A. et al. Soft porous silicone rubbers with ultra-low Soft, porousds in acoustic metamaterials. Sci. Rep. 7, 40106 (2017).

Gregory, S. M. et al. Nano-acoustic resonator with ultralong phonon lifetime. Sci. 370, 840–843 (2020).

Gao, N. et al. Acoustic metamaterials for noise reduction: a review. Adv. Mater. Technol. 7, 2100698 (2022).

Biçer, A., Nurettin, K., Olgun, A. K. & Ahmet, C. Broad omnidirectional acoustic band gaps in a three-dimensional phononic crystal composed of face-centered cubic Helmholtz resonator network. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 150, 1591–1596 (2021).

Aravantinos-Zafiris, N., Sigalas, M. & Katerelos, G. T. D. Complete acoustic bandgaps in a three-dimensional phononic metamaterial with simple cubic arrangement. J. Appl. Phys. 133, 065101 (2023).

Bilal, O. R., Ballagi, D. & Daraio, C. Architected lattices for simultaneous broadband attenuation of airborne sound and mechanical vibrations in all directions. Phys. Rev. Appl. 10, 054060 (2018).

Delibašić Marković, H., Kaleris, K., Papadogiannis, N. A. & Petrović, V. Comparative analytical and numerical investigation of the plasma density in atmospheric air generated by nanosecond laser pulses. Laser Physics Letters 21, 033001 (2024).

Kaleris, K. et al. On the correlation of light and sound radiation following laser-induced breakdown in air. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 53, 435207 (2020).

Kaleris, K. et al. Laser-plasma sound sources in atmospheric air: A systematic experimental study. JSV. 570, 118000 (2023).

Kaleris, K. Sound reproduction from laser-driven pulsed acoustic sources. PhD thesis (Electrical and Computer Engineering dept., University of Patras, 2021).

Oksanen, M. & Hietanen, J. Photoacoustic breakdown sound source in air. Ultrasonics 32, 327–331 (1994).

Ni Xiao-wu et al. On the generation of laser-induced plasma acoustic waves. Acta Phys. Sin. 7, 143 (1998).

Qin, Q. & Attenborough, K. Characteristics and application of laser-generated acoustic shock waves in air. Applied Acoustics 65, 325–340 (2004).

Bolaños, G. J., Pulkki, V., Karppinen, P. & Hæggström, E. An optoacoustic point source for acoustic scale model measurements. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 133, 221–227 (2013).

Kaleris, K. et al. Experimentally validated modeling of the optical energy deposition in highly ionized ambient air by strong femtosecond laser pulses. Eur. Phys. J. D. 75, 236 (2021).

Manikanta, Ε., Vinoth Kumar, L., Leela, C. H. & Prem Kiran, P. Effect of laser intensity on temporal and spectral features of laser generated acoustic shock waves: ns versus ps laser pulses. Appl. Optics 56, 6902–6910 (2017)

Harilal, S. S., Brumfield, B. E. & Phillips, M. C. Lifecycle of laser-produced air sparks. Phys. Plasmas 22, 063301 (2015).

Singh, A. P., Padhi, U. P., Joarder, R., Propagation of Relativistic Shock Wave Induced by Laser Spark in Quiescent Air. In Proceedings of FMFP, 163 (IIT Bombay, India, 2018).

Couairon, A. & Mysyrowicz, A. Femtosecond filamentation in transparent media. Phys. Rep. 441, 47–189 (2007).

Papeer, J. et al. Extended lifetime of high density plasma filament generated by a dual femtosecond–nanosecond laser pulse in air. New J. Phys. 16, 123046 (2014).

Kaleris, K., Orfanos, Y., Bakarezos, M., Papadogiannis, A. N. & Mourjopoulos, J. Experimental and analytical evaluation of the acoustic radiation of femtosecond laser plasma filament sound sources in air. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 146, 212–218 (2019).

Kaleris, K., Orfanos, Y., Bakarezos, M., Papadogiannis, A. N., & Mourjopoulos, J. The effect of plasma geometry on the acoustic radiation of laser filaments. Proc. Forum Acust. 1819–1826 (2020)

Hussain shah, S. K. et al. Laser induced breakdown spectroscopy methods and applications: A comprehensive review. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 170, 108666 (2020).

Vincent, G. et al. Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy Imaging for Material and Biomedical Applications: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Anal. Chem. 95, 49–69 (2023).

Murdoch, N. et al. Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy acoustic testing of the Mars 2020 microphone. P&SS 165, 260–271 (2019).

Sullenberger, R. M., Kaushik, S. & Wynn, C. M. Photoacoustic communications: delivering audible signals via absorption of light by atmospheric H2O. Opt. Lett. 44, 622 (2019).

Kaleris, K., Stelzner, B., Hatziantoniou, P., Trimis, D. & Mourjopoulos, J. Laser-sound: optoacoustic transduction from digital audio streams. Sci. Rep. 11, 476 (2021).

Kaleris, K., Stelzner, B., Hatziantoniou, P., Trimis, D. & Mourjopoulos, J. Laser-Sound Transduction from Digital ΣΔ Streams. JAES 70, 50–61 (2022).

Kaleris, K., Hatziantoniou, P., Stelzner, B. & Trimis, D. Laser-sound reproduction by pulse amplitude modulation audio streams. Sci. Rep. 14, 12102 (2024).

Dell, A., Krynkin, A., Horoshenkov, K. V. & Sailor, G. Low frequency attenuation of acoustic waves in a perforated pipe. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 153, 1791–1801 (2023).

Krynkin, A. & McIver, P. Approximations to wave propagation through a lattice of Dirichlet scatterers. Waves Random Complex Media 19, 347–365 (2009).

ASTM E2611-09. Standard Test Method for Measurement of Normal Incidence Sound Transmission of Acoustical Materials Based on the Transfer Matrix Method, (American Society for Testing and Materials, 2009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.A.P., K.K. and J.M. conceived the concept. K.K., N.A.P., E.Κ.Κ., M.B. and M.T. designed the experiments and developed the experimental platform. K.K., E.Κ.Κ. and N.A.P. carried out the experiments. N.A.Z., M.S. and D.T.G.K. designed, simulated and constructed the phononic crystals. K.K. wrote the data analysis software. Κ.Κ., E.K.K., N.A.P., J.M., M.B., V.D., N.A.Z. and M.S. analyzed the experimental and computational data. N.A.P. and M.T. supervised the experimental work and M.S. supervised the simulations. KK prepared the first draft. All authors revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

K.K. and J.M. are inventors in a German patent with file number 102021200293.5 where evaluation of acoustic structures via laser-plasma sound sources is described as a potential application of the presented laser-sound system. The rest of the authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Aldo Isidori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaleris, K., Kaniolakis-Kaloudis, E., Aravantinos-Zafiris, N. et al. Acoustic metamaterials characterization via laser plasma sound sources. Commun Mater 5, 93 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00529-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-024-00529-w