Abstract

Self-regulation, or a closed feedback-loop, is a recurring concept in biological control that supports the intelligent behaviors we observe in nature. Hence, replicating self-regulating properties in materials is a major goal in the pursuit of synthetic material intelligence. In this paper, we contribute to the advancement of material intelligence by incorporating our ‘active aperture’ design within liquid crystal oligomer network (LCON) soft actuators to achieve electrically-driven self-regulating behaviors; we harness the reversible thermal actuation of LCONs to establish a duty cycle around a chemically-adjustable threshold temperature in an on-board heating circuit. Utilizing this principle, we developed a self-regulating LCON proof-of-concept demonstrator that mimics the rhythmic compression of a biological heart, designed to oscillate around the 20 °C to 40 °C body temperature range. Hereby, we establish the precedent for the use of material intelligence towards advanced medical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Self-regulation is a core principle contributing to the resilience and adaptability we observe in nature and is essential to biological life1,2,3. Thus, self-regulating behaviors provide excellent inspiration for the next function of synthetic material intelligence to develop, which would contribute to the advance towards robotic biomimicry, complex prosthetics and fully artificial implants4,5,6,7. Currently, for such devices, researchers typically use extraneous digital control systems to coordinate multiple electronic sensing and actuation components8,9,10,11. However, signal processing for disparate components is hindered by their different material compositions, which in turn raises challenges for the incorporation of multi-functional adaptability within a single unit12,13,14. Moreover, combining sensor, control and actuation functions to make a self-regulating device entails the added challenge of producing a device that can operate within the conventional electrical infrastructure of modern electronics and industry. In the face of this challenge, we recognize the potential to achieve this technological development in the field of soft robotics through stimuli-responsive materials. Classic examples are chemo-mechanical self-regulating hydrogels, in which internally fueled reactions drive autonomous swelling–deswelling or bending cycles without external on–off control13. However, such self-regulating gels typically rely on multi-component chemistries, continuous chemical fuel and oscillation periods on the order of minutes, which limits their direct integration with fast, electrically driven soft robotic devices.

In parallel, the programmable photonic, thermal and electrical responsiveness of liquid crystal oligomer networks (LCONs) has elevated their status in the world of soft robotics as ideal compliant stimuli-responsive actuators with reversible actuation15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. This behavior is driven at the molecular level, namely through molecular alignment in liquid crystal phases, offering a major advantage in programmability26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34; the deformation geometry of LCONs can be localized and adjusted through alignment design, while the kinetics, magnitude and thermal threshold for the deformation response of LCONs can be tailored by inducing certain phases and phase-transitions, such as smectic-nematic or nematic-isotropic, within the expected operating parameters of the actuator35,36,37. In all cases, they experience deformation when molecular alignment is disturbed, for instance through optical or thermal energy, which is reversed when the stimuli is removed. This conditional deformation behavior has been applied to generate basic material-based logic, embodying the potential for material intelligence when incorporated into devices38,39. For example, self-regulated actuators based on self-shadowing effects or thermal gradients have been developed that exhibit continuous rolling, rocking or cantilever oscillations40,41,42,43. In self-shadowing schemes, robust oscillation requires a precisely controlled angle of incidence of the light source, whereas in thermal-gradient-driven self-regulation, feedback relies on tailored geometry or alignment together with an external heat source to create spatial temperature gradients. This sensitivity to illumination conditions and structural design limits the compatibility of such systems with conventional electronically driven devices.

Therefore, in our work, we present an electrically powered, single-material LCON architecture that integrates sensing, actuation, and feedback into a compact self-oscillating unit. To achieve this, we use our ‘active aperture’ design to control an electrically-driven, programmable self-regulating LCON system as a single-material adaptive unit. Our control system allows for on-board circuitry for our LCON, enabling our device to be designed as a single-material unit through additive manufacturing processes; sensing, control and actuation circuits are printed onto our LCON system, after which the ‘active aperture’ is incorporated mechanically. Below a predetermined threshold temperature (Tth), the active aperture is closed and allows for Joule heating to take place until the threshold temperature is surpassed, which causes the active aperture to open and subsequently break the circuit, enabling the system to begin cooling to below the threshold temperature, resetting the cycle; thus, this device configuration enables a negative closed-feedback loop to be established. Based on this concept, we developed a self-regulating LCON proof-of-concept demonstrator that oscillates around body temperature, mimicking the rhythmic compression of a biological heart. We envision our work as a step toward future advancements in material intelligence for adaptive and programmable medical technologies.

Results and Discussion

Self-regulation principles

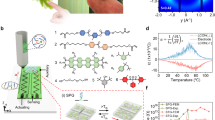

To construct a self-regulating device, our material design combines sensor, control and actuation functions within an electrically-driven framework. For this purpose, we apply our active aperture LCON control to establish self-regulation that is powered electrically and switched thermally, as described in Fig. 1a; this results in a four-stage closed-feedback loop that involves Joule heating, subsequent active aperture activation to break the heating circuit, successive material cooling, and LCON relaxation to deactivate the active aperture, reconnecting the heating circuit and resetting the feedback loop. The core of our self-regulating function is based on the thermal responsiveness of our LCONs, which we tune to an operational range between 20 °C to 40 °C for improved suitability for human-interactions, considering the average human body temperature range of 33 °C to 37 °C44, by balancing our shorter-core and longer-core liquid crystal composition, labeled Molecule 1 and Molecule 2 in Fig. 1b. Our liquid crystal mixture is initially cured into an oligomeric form through thiol-Micheal addition reactions with a chain-extending molecule, labeled Molecule 3 in Fig. 1b, catalyzed by a basic amine; additional undesired polymerization of liquid crystal oligomers during processing is prevented by the inclusion of inhibitor molecules, labeled Molecule 4 in Fig. 1b. After the initial curing stage, liquid crystal alignment can be induced mechanically through strain or shear, which can then be arrested into the material for permanent reversible actuation by second-stage in-situ photopolymerization-based curing, enabled by the inclusion of photo-initiating molecules in the initial synthesis, labeled Molecule 5 in Fig. 1b.

a Operating principle of the active-aperture LCON in a ring configuration; the feedback loop flows clockwise. b Structural formulae of materials used in the composition of our LCON material. c WAXS analysis data showing the presences of liquid crystal phases with temperature for an pure M1 LCON; the position of the smectic layer scattering signal is highlighted. d WAXS analysis results of LCON with pure M 1 – annotations highlight the data showing the smectic phase in the material. e The polarized optical microscope images of the printed LCON films. The red arrow annotation indicates the direction in which the printing nozzle extrudes our oligomer material. Scale bar: 300 µm. f Graphical representation of the order parameter change of LCONs with temperature. g Expanded WAXS analysis, showing distances between smectic layers (dsm) and molecular spacing (dN) in the nematic phase with varying concentration of M 2. h Graphical representation of the thermal strain data of a pure M 1 LCON and an LCON with a 60 mol. % M 2 composition from 20 °C to 40 °C. i Graphical representation of the ratio of the change of thermal strain and the change of order parameter with temperature.

The actuation response of the resulting LCON material is strongly dependent on the liquid crystal phases and phase transitions temperature present in the operating parameters. Therefore, we performed wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS), described in Fig. 1c,d and Supplementary Fig. S1, to confirm that our LCONs, consisting only of short-core reactive mesogens (M1), retain a smectic phase until 60 °C. In our work, we describe the alignment of our material with an scalar order parameter (S), a standard metric based on the average adherence of molecular orientation to a general director. Our materials presents a typical S of 0.4, which indicates relatively well-aligned mesogens within the LCON, confirmed also by polarized optical microscopy images (Fig. 1e). From the WAXS results, we observe the S of our M1-based LCONs gradually decreases with temperature to execute an actuation, as shown in Fig. 1f.

LCON composition design offers us the possibility to engineer the phases and phase transitions of our material to suit our operating parameters. Introducing M2 into our LCONs disturbs the smectic phase. In the oligomeric state, this smectic phase was fully suppressed at 20 mol. %, introducing the nematic phase (Supplementary Fig. S2). Yet, the photopolymerization process reinforces the smectic phase due to polymerization shrinkage; as a result, 100 mol. % is required to fully transform the smectic phase to the nematic phase at room temperature. This phenomena is confirmed by WAXS, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. Further focusing on the morphology, an increase in the smectic layer distances (dsm) is observed with initial M2 addition (Fig.1g). We hypothesize that this is caused by the initial mismatch between M1 and M2, causing poorer molecular packing in the smectic phase. Yet, further increasing M2 concentration leads to dsm decreasing, as M2 is a shorter molecule. Conversely, we also investigated the intermolecular spacing (dN) in the nematic phase, which reflects the opposite trend in regards to dsm for the same reason; this is supported by the transitions observed in the differential scanning calorimetry data in Supplementary Fig. S2. The phase influences the actuation behavior; therefore, we can compare the thermal strain of pure M1 with various compositions including M2, shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. Our typical samples consist of M1 with 60 mol. % M2 additions, which have lowered temperature requirements for actuation, resulting in thermal strain of about 5% in the range from 20 °C to 40 °C, as shown in Fig. 1h. For M2 concentrations below 60 mol. %, thermal strain increase with M2 since it disturbs the higher-ordered smectic alignment. Yet, over 60 mol. %, M2 addition reduces the thermal strain since M2 increases the nematic-isotropic transition temperature. Overall, for all systems, the order parameter decreases with temperature, which leads to actuation. We describe the origin of this macroscopic deformation through the collective action of microscopic molecular events, for which we define the relationship between thermal strain and order parameter in Fig. 1i. The influence of order parameter on the thermal strain was observed to be smaller in the smectic state because of additional positional order affording lower mobility. Therefore, we believe that the addition of M2 increases thermal response by reducing the presence of the smectic phase at the lower temperatures. Hence, LCONs containing 60 mol% M2 were selected as the optimal material for our self-regulating LCON proof-of-concept demonstrator, due to their ability to achieve the maximum possible thermal strain within the 20–40 °C human-interactive temperature range.

LCON device and active aperture design

The thorough quantification of the material properties of our LCONs sets the basis for our active aperture and overall self-regulating device design, illustrated in detail in Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. S5. Here, we showcase our heating element, a composite of silver and carbon that exhibits high resistivity. We design this electrode in a zig-zag pattern with a pre-determined vertex angle (α), selected to minimize local mechanical stress on the electrode during actuation and avoid breakage while homogenizing heat transfer during Joule heating. The optimal vertex angle of 55 ° was determined through Finite Element Modeling (FEM) depicted in the illustrations in Fig. 2b and described in the results in Fig. 2c, where the α with the minimum Von Mises stress, a scalar parameter for stress, generated along a chosen strip of the electrode is selected; additional simulation details are shown in Supplementary Note S1. The FEM simulation was conducted to confirm and understand the stress variation at the interface in our active aperture design as well (Fig. 2d), where the stress distribution is analyzed in the open and closed states, corresponding to the thermal actuation of the LCON material below and above the Tth, respectively; the actuation of the LCON material is shown to apply tension, marked in blue, on the sensing electrode to pry it apart (Fig. 2d(iv)), while LCON relaxation compresses, marked in red, the sensing electrode to reconnect it (Fig. 2d(iii)). When the sensing electrode length exceeds 1.5 mm, closure is reliable (Fig. 2e). Meanwhile, because the aperture is a bilayer film, deformation mismatch during cooling causes bending that becomes more pronounced for longer electrodes, leading to misalignment of the aperture. Therefore, a balanced electrode length of 2.5 mm was selected as the optimized design; more details about the simulation are shown in Supplementary Note S2. Initially, at room temperature, the aperture is closed; this is achieved by creating the aperture at an elevated temperature during curing, closing the aperture as the LCON contracts when cooled. We then confirm the opening and closing of our aperture through the resistance measurements across the sensing electrode, visualized in Fig. 2f and Supplementary Movie 1; the simulations agree with our experimental results, as presented in Fig. 2g. The abrupt increase in sensing electrode resistance around the threshold temperature indicates that the threshold temperature is exceeded. In the open state, the simulated resistance is about four orders of magnitude higher than the experimental result, which is limited by the instrument’s maximum detection range of ~210 MΩ. Hereby, the combined sensing and actuation function of our active aperture design is demonstrated.

a Schematic of a self-regulating LCON ring and its unwrapped view. The unwrapped top- and side-view schematics show the placement, embedding, and geometry of the electrical traces. Red annotations mark the active aperture and the zig-zag actuating electrode with vertex angle α. The α represents the angle between the actuating electrode and the liquid crystal director (\(\hat{{{\boldsymbol{n}}}}\)). b FEM simulation diagram of the actuation electrode trace, where the local von Mises stress distribution is measured across a selected line marked as L1. c The simulated local Von Mises stress distribution along marked path L1 for a range of α. d The schematic and FEM simulation of the active aperture function in the (i, iii) close and (ii, iv) open states, showing the stress in the system when below and above the temperature threshold, and the corresponding closed and open states. e The FEM results showing the contact pressure at the electrode interface as a function of sensing electrode length L (inset), which was used to optimize the active aperture design. f Optical microscopy image of the sensing gap at above and below the pre-programmed threshold temperature; scale bar represents 100 µm length. g Graphical representation of the electrical resistance of the active aperture against the ratio of actual temperature (Tac) to the set threshold temperature (Tth) of 28 oC; the recorded trend obtained from finite element modeling and experiment is compared.

Electrical operation of the LCON active aperture system

Utilizing the optimized design for our LCON active aperture, we validated the electrical operation of our device experimentally. The printed unwrapped device is shown in Fig. 3a(i), exhibiting a uniform heating profile when 8 V is applied to the actuation electrode as shown in Fig. 3a(ii). The macroscopic output was quantified as contractile force (Fig. 3b), with a force density of ~0.1 mN mm⁻². The LCON film was assembled into a ring configuration for further characterization. As shown in Fig. 3c and Supplementary Movie 2, the ring diameter decreased progressively with increasing input voltage. The corresponding average surface temperature remained below ~43 °C for voltages up to 10 V (Supplementary Fig. S6). Next, Fig. 3d shows, through a circuit diagram, how our active aperture structure is integrated as the sensing electrode, denoted by R1, connected in series with the actuating electrode, denoted by R2. Initially, when the active aperture is closed, the voltage is divided mainly over R2 due to its higher resistance, which induces Joule heating in the system and activates LCON actuation. This generated heat is then transferred to the LCON active aperture, producing a temperature gradient; when this heat transfer induces the aperture temperature to reach Tth, the active aperture actuates and opens, interrupting the flow of current and preventing further Joule heating. Thus, the LCON cools down by natural convection within the ambient environment until the aperture temperature falls below Tth, causing the aperture to close again and initiate a new heating-cooling cycle. Within this type of self-regulation, oscillation occurs due to the thermal delay introduced by temperature differences between the aperture and actuation electrode and the thermal hysteresis effect of LCONs (Fig. 1h). After the active aperture is opened, this temperature difference and thermal hysteresis effect postpones the system from immediately closing the active aperture.

a The top view of the printed sample (i) and thermal profile (ii) during actuating of the LCON device. b Graphical analysis of the contractile force and kinetics of the LCON self-regulating device between an operating potential difference range of 5-9 V. c Graphical analysis of the contractile displacement of the LCON device with applied potential difference; a 3D schematic of the exact contractile motion of the LCON device is embedded. d Circuit diagram of the on-board LCON circuitry, where R1 and R2 denote the presence of the resistances in sensing and actuating electrodes respectively. e Real images of the LCON device before and during oscillating; a small red square marker is affixed at the bottom of the ring to monitor actuation amplitude. f Graphical thermal (i), actuation (ii) and voltage (iii) analysis of the LCON device in the oscillation state. g Statistical analysis of oscillation frequency within a 120 s interval under different applied voltages, where error bars represent the variation in frequency during the measurement period. h Graphical analysis of the effect of the distance between actuating and sensing electrode on the required threshold power for triggering oscillation.

In Fig. 3e, we present the images of the electrothermal actuation of our LCON device based on this principle, focusing on the oscillation amplitude of diameter (∆d) (Fig. 3e) and the corresponding thermal profiles are shown in Supplementary Fig. S7. As shown in Fig. 3f, the oscillatory behavior of the system is related to the temperature difference between actuating electrode and aperture; the resulting deformations correspond to the output voltage across R1, since a low output voltage indicates the aperture is closed and vice versa. The entire oscillating process is recorded in Supplementary Movie 3. This data provides insight into the self-regulating behavior of our LCON device, which we utilize to demonstrate feedback-loop adjustments through tuning of the applied voltage as shown in Fig. 3g. We observe that the frequency of oscillation is amplified by increasing the applied potential difference. This occurs because higher voltages entail more power and faster generation of heat through Joule heating, subsequently transferring energy quicker to open the aperture. Meanwhile, the threshold power required to initiate oscillation was found to increase with the distance between the actuating and sensing electrodes (Fig. 3h); greater separations demand greater heat generation from the actuating electrode, thereby requiring higher input power. To evaluate long-term robustness, we monitored oscillations over extended operation. The system maintained autonomous cycling for >48 h, completing >150,000 aperture open–close cycles (Supplementary Fig. S8). Peel tests measured interfacial strength of ~2–3 MPa (Supplementary Fig. S9), and Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) image revealed an interdigitated interface, indicating mechanical interlocking (Supplementary Fig. S10). This strong adhesion supports reliable cyclic operation. However, because aperture actuation involves repeated mechanical contact, prolonged cycling led to gradual wear of the conductive electrodes. The resulting rise in local contact resistance caused extra Joule heating and slower cooling, which in turn reduced the oscillation frequency over time.

LCON self-regulating devices for bio-inspired actuation

To demonstrate the potential application of our oscillation ring, we constructed a heart-inspired soft robotic model in which our LCON material provides oscillatory compression of an elastic reservoir in a proof-of-concept demonstrator. The design of our demonstrator is illustrated in Fig. 4a(i), which is split into three sections. The outermost section is a heart-shaped casing used only for demonstration purposes, constructed by epoxy resin through 3D printing. The functional inner section is most crucial, focused on in Fig. 4a(ii), since it consists of our active LCON self-regulating material assembled in a ring configuration with printed electrodes; our system is powered by a battery with a flexible printed circuit board (F-PCB) interface (Supplementary Fig. S11). The final section is the reservoir, consisting of a tube and an elastic tank that is rhythmically compressed by our LCON material; to prevent unnecessary heating of the fluid in the tank, three thermal insulation blocks are placed between the LCON ring and the elastic tank; the final assembled device as a whole is shown in Fig. 4b. The actuation performance of our demonstrator was first evaluated in a direct, non-oscillatory mode. As shown in Fig. 4c, a single full contraction at 10 V extruded ~2 μL of liquid in the open-tube configuration, with smaller volumes recorded under sealed conditions because the generated back pressure not only resisted fluid ejection but also deformed the compliant reservoir, storing part of the stroke internally. Furthermore, the oscillatory function of our heart-inspired soft robotic model is gauged both electronically and mechanically, presented in Fig. 4d, Fig. 4e and Supplementary Movie 4, respectively. In the self-regulating regime, the LCON ring is biased into a quasi-steady contracted state and oscillates around this mean diameter with a maximum frequency of ~180 oscillations per minute. In this configuration, the reservoir experiences a net volume change of about 0.6 μL between the relaxed and mean deflected state (Fig. 4e), which is much <2 μL obtained under a single full stroke (Fig. 4c). Because the oscillation amplitude around the mean actuated state is limited, the fluid displacement per oscillation is only microscopic, not discernible to the naked eye and therefore contributes little to the measured net volume change, even though the oscillatory behavior is clearly visible in the electrical signal (Fig. 4d). Addressing this limitation by increasing the volume displaced per oscillation will be an important objective in future work. Since our material is electrothermally-responsive, its adaptability originates from the thermal responsiveness of the actuator material itself rather than an external controller, unlike a biological heart. Yet, the construction of this heart-inspired demonstrator with our LCON material is a proof-of-concept for its potential for self-regulating material intelligence. Moreover, the additive manufacturing processes used to prepare our demonstrator is a positive indicator of its scalability, and sets a powerful precedent for the construction of full-functional, human-interactive LCON device.

a Schematic of (i) the heart-inspired LCON soft robotic demonstrator and (ii) the operating mode of the self-regulating LCON device. b Photographs of the heart-inspired demonstrator: (i) assembled device with the heart-shaped casing; (ii) functional device without the casing, showing the LCON ring, reservoir and electronics. c Graphical analysis of the liquid displacement of the LCON myocardium with applied potential difference; a 3D schematic of the experimental setup is embedded. d Graphical analysis of the oscillatory behavior of the LCON soft robotic heart electronically, namely measurement of the voltage across the active aperture over operation. e Graphical analysis of oscillatory mechanical deformation of heart-inspired soft robotic demonstrator over time.

Conclusion

By the quantification of the multi-stimuli, self-regulating behaviors of our LCON within an electronic framework, we demonstrate its potential for intelligent functions. We are able to design and operate our LCON actuators as a result of our material optimization processes; aided by WAXS, we formed a thorough understanding of the LC phase-transition-based actuation of our material in terms of the molecular structure and morphology of its constituents. Enabled by additive manufacturing processes, we used our data to create and analyze our active aperture design for LCON self-regulation, which we then optimized with guidance from analysis of finite element modeling. We exhibited the finely-tunable oscillation of our LCON devices with electrothermal stimuli, revealing the potential for hybrid circuit designs and applications within the conventional electrical infrastructure of modern devices. Ultimately, we utilized our LCON device design to integrate actuation, sensing, and control within a single material, demonstrated within a proof-of-concept soft robotic heart model. While not intended directly as a biomedical implant, this study establishes a foundation for exploring LCON intelligent materials in adaptive bio-interfacing and future medical technologies. We aspire to advance the material-to-device transition of LCONs through this research and inspire further innovations for our materials in the soft robotics field.

Experimental

Materials

An overview of the typical materials for the self-regulating unit is provided in Fig.1c. Molecule 1 4-(6-(Acryloyloxy)hexyloxy)phenyl 4-(6-(acryloyloxy)hexyloxy) benzoate was acquired from Daken Chemical Limited. Molecule 2 2-Methyl-1,4-phenylene bis (4-(3-(acryloyloxy)propoxy)benzoate) was purchased from Merck. Molecule 3 2,2’-(Ethylenedioxy) diethanethiol, Molecule 4 Butylated hydroxytoluene and basic catalyst (1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene, DBU) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Molecule 5 (Irgacure 819) was purchased from Ciba. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) with an average molecule weight of 25000 g/mol was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Dichloromethane (DCM) was obtained from Biosolve. Two conductive inks, PE671 (carbon-based) and PE874 (silver-based) were purchased from Dupont. Another silver-based conductive ink (Elepaste NP1) was acquired from Taiyo.

Synthesis of liquid crystal oligomers

Liquid crystal oligomers were synthesized using a base-catalyzed thiol-acrylate Michael addition. Typically, the molar ratio of acrylate to thiol is ~1:0.91 and the molar ratio of Molecule 1 to Molecule 2 is 2:3. To optimize the thermal properties of the LCON, the ratio of Molecule 2 varied. The typical synthesis procedure involved combining Molecule 1 (861.7 mg), Molecule 2 (1412.6 mg), Molecule 3 (663.57 mg), Molecule 4 (2.5 mg), and Molecule 5 (20 mg) in a vial. Subsequently, 10 mL of DCM was added to dissolve the mixture, followed by the addition of the base catalyst DBU (10 μL). After stirring for 3 h at room temperature and an additional 3 h at 50 °C hot plate to evaporate part of the DCM, the solution was transferred to a poly(tetrafluoroethylene) evaporation dish. It was then placed in a vacuum oven at 45 °C overnight to remove the remaining DCM solvent. Finally, the oligomer was loaded into an ink syringe for 4-D extrusion printing.

Preparation of the conductive inks

For printing the sensing and auxiliary electrodes, a pure commercial conductive ink (Elepaste NP1) was used. For printing actuating electrodes, a conductive ink mixture was prepared by blending the PE671 and PE874. The two conductive inks were directly added to the vial and mechanically stirred for 10 min. The conductivity of the blended mixture increased with higher PE874 concentrations. Typically, a mixture containing 50 wt% PE874 and 50 wt% PE671 was used for preparing the actuating electrode. Its conductivity is about ten times lower than the pure Elepaste NP1. Finally, the two tailored conductive inks were loaded into separate syringes.

The fabrication of the self-regulating unit

Using commercial 3D printers (EHR, Hyrel 3D), a multi-step direct ink writing procedure was used to manufacture the self-regulating unit38. Firstly, a PVA sacrificial layer was spin-coated onto the glass substrate before printing. Following this, the blended conductive ink and the pure Elepaste NP1 ink were used to print the actuating, sensing and auxiliary electrodes. After printing, the conductive inks were heat-cured at 120 °C for 30 min. Above the conductive ink layers, the liquid crystal oligomer was extruded onto the substrate at the area of the active aperture and photopolymerized above room temperature. Next, additional oligomer material was then extruded onto the substrate in the rest area. Unlike the curing process for the primary printed oligomer area, the secondary printed area was typically photopolymerized at ambient temperature. Next, the printed samples were carefully peeled off their substrate after immersion in water to dissolve the PVA layer. The freed samples were then dried in air to remove any water remaining at their surfaces. Finally, the sensing electrodes and the LCON film were cut through with a handmade die, thus creating the initial micro-gap as the aperture. This process was performed above room temperature, enabling the initial micro-gap to close upon cooling back to room temperature.

The fabrication of the heart-inspired demonstrator

A commercial SLA 3D printer (Formlabs 3) was used to print the heart-shaped casing, the insulation blocker, and the cap of the reservoir. The elastic resin Elastic 50 A V1 was used to print the heart-shaped casing and the cap of the reservoir, while the rigid resin Grey V4 was used to insulation blocker. After 3D printing, the cap of the reservoir was glued to the elastic tank made from the Nitrile glove. Then three insulation blockers was glued into the surface of the elastic reservoir. And the printed self-regulating LCONs connected with flexible PCB was carefully assembled with the elastic reservoir. After that, a micro medical tubing (LDPE 0.045 inch I.D. × 0.062 inch O.D., from Scientific Commodities, Inc.) was connected to the cap of the reservoir. A UV glue was used to fill the gaps to ensure a high degree of airtightness. In some experiments (Fig. 4e), a smaller Flexible Fused Silica capillary (ID 536 µm +/−6 µm, OD 665 µm +/−15 µm, from CM Scientific Ryefield (EU) Ltd.) was connected to the end of the LDPE tube to visualize the process of liquid flow in minute quantities. Meanwhile, a gel food color dye (Bright red, Dr. Oetker) was dissolved in the water, which was injected into the reservoir via a syringe to fill the entire reservoir and part of the tube. This dye was also used to color the heart-shaped casing into red to mimic the real heart. Finally, the flexible PCB was connected to the battery to power the heart-inspired demonstrator.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

DSC measurements were employed to determine the transition temperature of oligomers in TA Instruments DSC Q1000. The sample was heated and cooled at a rate of 10 °C min−1 from −50 °C to 100 °C. This cycle was performed twice, with the first cycle being used to eliminate the thermal history accumulated during the preparation the sample.

Wide-angle X-ray scattering analysis

X-ray scattering measurements were performed on a Ganesha lab instrument equipped with a Genix-Cu ultralow divergence source that generates X-ray photons with a wavelength and flux of 0.154 nm and 1 × 108 photons s-1, respectively. Diffraction patterns were obtained using a Pilatus 300 K silicon pixel detector with 487 × 619 pixels of 172 × 172 μm2. Silver behenate was used as a calibration standard. The sample-to-detector distance was 89 mm for wide-angle (WAXS) configurations. The WAXS results were used to analyze liquid crystal phase and order parameters of the LCONs.

Dynamic mechanical thermal analysis (DMTA)

Using a TA Instruments Q800 device in vertical tension mode, dynamic mechanical thermal analysis was performed on thin films. The force-controlled mode was chosen to measure the thermal strain in the LCON film with uniaxial alignment. The sample was cooled to 20 °C and equilibrium was held for 5 minutes with a pre-load force of 0.005 N. The 0.005 N static force was retained while the sample was heated to 40 °C and cooled at a rate of 5 °C/min. This cycle was performed twice to remove the thermal history of the material. Young’s modulus in the aligned LCON and the cured conductive ink was measured by cutting the film into rectangular pieces about 5 mm by 15 mm in size. The film had a thickness of ~100 µm. Thermographs were obtained with a single 1 Hz oscillating frequency, 0.05 N preload force, 50 µm amplitude, and between −20-100 °C at a heating rate of 5 °C min-1. For the adhesion strength measurement, Thin-film sample consisting of LCON layers bonded with printed electrodes were prepared with lengths of about 12 mm, widths of about 4.8 mm, and total thicknesses of about 220 μm (LCON ≈ 200 μm, electrode ≈ 20 μm). The initial bonded region was about 6 mm in length. Samples were mounted with the bonded region fixed in the clamps and subjected to force-controlled loading to assess interfacial adhesion. Force–displacement and stress–displacement curves were obtained by pulling until interfacial separation occurred. Tests were performed at room temperature with a preload of 0.005 N, and stresses were calculated based on the nominal bonded area.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) imaging

A JEOL JSM-IT100 scanning electron microscope operating at a 5 kV acceleration voltage was used to capture the SEM images to study the interface between the electrode and LCONs.

Electrical characterization

To measure resistance and current changes during sensing and actuating, the free-standing LCON device was mounted on a 3D-printed custom-built clamp where four copper wires with a diameter of 100 µm were fixed on the surface. Two copper wires were connected to the sensing electrodes, while the other two were connected to the actuating electrodes. To provide a constant input voltage for the LCON device, a DC power source (TENMA 72-2720) was used. The resistance and the current of the LCON device were measured using a source meter (Keithley 2400), and a digital oscilloscope (RTB 2004) was used to track the voltage. MATLAB (R2019a) was used as a control platform during the measurement. In the characterization of the artificial heart, the active LCON ring was connected to a flexible PCB, and the flexible PCB was connected to the DC power source or battery.

Optical characterization

The alignment of the printed LCON film was checked using a polarization optical microscope (Leica DM 2700 M). A digital camera (OLYMPUS E-M10 Mark IV, 60 mm lens) was used to capture photographs and videos. A USB camera (60 fps, 2 MP) was used to investigate the closed feedback loop in the single adaptive electronic unit. An infrared camera (Xenics, Gobi + 640 GigE) was used to capture thermal images/videos. Video analysis software (Tracker, version 6.1.0) was used to track the bending deformation in the free standing film, the diameter of the ring change, the extruded liquid volume change in the artificial heart.

Simulation of the self-regulating system

All FEM analysis was conducted using the COMSOL Multiphysics (v.6.1a). The detailed setup and parameters can be found in Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Note 2.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Vis, A. et al. The ongoing quest for the first total artificial heart as destination therapy. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 19, 813–828 (2022).

Cohrs, N. H. et al. A soft total artificial heart—first concept evaluation on a hybrid mock circulation. Artif. Organs 41, 948–958 (2017).

Segerstrom, S. C. & Nes, L. S. Heart rate variability reflects self-regulatory strength, effort, and fatigue. Psychol. Sci. 18, 275–281 (2007).

Weymann, A. et al. Artificial muscles and soft robotic devices for treatment of end-stage heart failure. Adv. Mater. 35, e2207390 (2023).

Park, C., Ozturk, C. & Roche, E. T. Computational design of a soft robotic myocardium for biomimetic motion and function. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2206734 (2022).

Rosalia, L. et al. Soft robotic patient-specific hydrodynamic model of aortic stenosis and ventricular remodeling. Sci. Robot. 8, 1–13 (2023).

van Laake, L. C. & Overvelde, J. T. B. Bio-inspired autonomy in soft robots. Commun. Mater. 5, 1–8 (2024).

Cohn, W. E., Timms, D. L. & Frazier, O. H. Total artificial hearts: Past, present, and future. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 12, 609–617 (2015).

Andriollo, M., Fanton, E. & Tortella, A. A review of innovative electromagnetic technologies for a totally artificial heart. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13031870 (2023).

Liao, W. & Yang, Z. The integration of sensing and actuating based on a simple design fiber actuator towards intelligent soft robots. Adv. Mater. Technol. 7, 1–9 (2022).

Ham, J., Han, A. K., Cutkosky, M. R. & Bao, Z. UV-laser-machined stretchable multi-modal sensor network for soft robot interaction. npj Flex. Electron. 6, 1–9 (2022).

McEvoy, M. A. & Correll, N. Materials that couple sensing, actuation, computation, and communication. Science. 347, 6228 (2015).

He, X. et al. Synthetic homeostatic materials with chemo-mechano-chemical self-regulation. Nature 487, 214–218 (2012).

Li, S. et al. Self-regulated non-reciprocal motions in single-material microstructures. Nature 605, 76–83 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Liquid crystal elastomer based dexterous artificial motor unit. Adv. Mater. 35, 1–10 (2023).

Astam, M. O., Lyu, P., Peixoto, J. & Liu, D. Self-regulating electrical rhythms with liquid crystal oligomer networks in hybrid circuitry. Soft Matter. 18, 7236–7244 (2022).

Ware, T. H. et al. Voxelated liquid crystal elastomers. Science 347, 982–984 (2015).

Yao, M., Wu, B., Feng, X., Sun, S. & Wu, P. A highly robust ionotronic fiber with unprecedented mechanomodulation of ionic conduction. Adv. Mater. 33, 2103755 (2021).

Chen, Y. & Valenzuela, C. Article Biomimetic artificial neuromuscular fiber bundles with built-in adaptive feedback biomimetic artificial neuromuscular fiber bundles with built-in adaptive feedback. Matter 8, 101904 (2025).

Geng, Y., Kizhakidathazhath, R. & Lagerwall, J. P. F. Robust cholesteric liquid crystal elastomer fibres for mechanochromic textiles. Nat. Mater. 21, 1441–1447 (2022).

López-Valdeolivas, M., Liu, D., Broer, D. J. & Sánchez-Somolinos, C. 4D printed actuators with soft-robotic functions. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 39, 3–9 (2018).

Zhan, Y., Broer, D. J., Li, J., Xue, J. & Liu, D. A cold-responsive liquid crystal elastomer provides visual signals for monitoring a critical temperature decrease. Mater. Horizons 10, 2649–2655 (2023).

Peng, X. et al. 4D printing of freestanding liquid crystal elastomers via hybrid additive manufacturing. Adv. Mater. 34, e2204890 (2022).

Ma, J.et al. Mechanochromic, shape-programmable and self-healable cholesteric liquid crystal elastomers enabled by dynamic covalent boronic ester bonds. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 61, e202116219 (2022).

He, Q. et al. Electrospun liquid crystal elastomer microfiber actuator. Sci. Robot. 6, 57 (2021).

Mbanga, B. L., Ye, F., Selinger, J. V. & Selinger, R. L. B. Modeling elastic instabilities in nematic elastomers. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter. Phys. 82, 4–7 (2010).

Lv, J. A. et al. Photocontrol of fluid slugs in liquid crystal polymer microactuators. Nature 537, 179–184 (2016).

Zuo, B., Wang, M., Lin, B.-P. P. & Yang, H. Visible and infrared three-wavelength modulated multi-directional actuators. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–11 (2019).

Ma, S., Li, X., Huang, S., Hu, J. & Yu, H. A light-activated polymer composite enables on-demand photocontrolled motion: transportation at the liquid/air interface. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 58, 2655–2659 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Experimental insights into the nanostructure of the cores of topological defects in liquid crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 1–5 (2016).

Shahsavan, H., Yu, L., Jákli, A. & Zhao, B. Smart biomimetic micro/nanostructures based on liquid crystal elastomers and networks. Soft Matter 13, 8006–8022 (2017).

Shahsavan, H. et al. Bioinspired underwater locomotion of light-driven liquid crystal gels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 5125–5133 (2020).

Zhao, H., Tai, J. S. B., Wu, J. S. & Smalyukh, I. I. Liquid crystal defect structures with Möbius strip topology. Nat. Phys. 19, 451–459 (2023).

Yuan, Y., Liu, Q., Senyuk, B. & Smalyukh, I. I. Elastic colloidal monopoles and reconfigurable self-assembly in liquid crystals. Nature 570, 214–218 (2019).

Ren, L. et al. Programming shape-morphing behavior of liquid crystal elastomers via parameter-encoded 4D printing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 15562–15572 (2020).

Hebner, T. S., Korner, K., Bowman, C. N., Bhattacharya, K. & White, T. J. Leaping liquid crystal elastomers. Sci. Adv. 9, 1–8 (2023).

Davidson, E. C., Kotikian, A., Li, S., Aizenberg, J. & Lewis, J. A. 3D Printable and reconfigurable liquid crystal elastomers with light-induced shape memory via dynamic bond exchange. Adv. Mater. 32, 1905682 (2020).

Lyu, P., Broer, D. J. & Liu, D. Advancing interactive systems with liquid crystal network-based adaptive electronics. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–9 (2024).

He, Q. et al. A modular strategy for distributed, embodied control of electronics-free soft robots. Sci. Adv. 9, 27 (2023).

Zhao, Y. et al. Twisting for soft intelligent autonomous robot in unstructured environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, 1–10 (2022).

Gelebart, A. H. et al. Making waves in a photoactive polymer film. Nature 546, 632–636 (2017).

Deng, Z., Li, K., Priimagi, A. & Zeng, H. Light-steerable locomotion using zero-elastic-energy modes. Nat. Mater 23, 1728–1735 (2024).

Vantomme, G., Gelebart, A. H., Broer, D. J. & Meijer, E. W. Self-sustained actuation from heat dissipation in liquid crystal polymer networks. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 56, 1331–1336 (2018).

Goto, T., Niu, Z., Chiba, Y., Amano, K. & Saijo, Y. Human body temperature and cardiovascular response to changes in ambient temperature and body posture. Build. Environ. 266, 112085 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the financial support from the ICMS-CRT STA Neural Networks project. We thank the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO OCENW.KLEIN. 10854, START-UP 8872), NWO Sectorplan and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 956150 (STORM-BOTS) for financial support. We would like to thank professor D.J. Broer for demystifying LCON materials for us.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.L. and M.O.A. contributed equally to this work. P.L., M.O.A. and D.L. conceived the project and designed the overall research plan. P.L. designed and performed the material synthesis, device fabrication and most of the experiments, and analysed the data. M.O.A. led the writing of the manuscript and contributed to data analysis. O.L. contributed to the experimental work, data analysis and figure preparation. D.L. supervised the project and provided overall guidance. All authors discussed the results, revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks Qiguang He and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lyu, P., Astam, M.O., Ouassim, L. et al. Multi-functional liquid crystal oligomer networks for human-interactive self-regulation. Commun Mater 7, 38 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-01048-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-01048-y