Abstract

Carbon quantum dots (CQDs) have emerged as highly promising multifunctional nanomaterials for next-generation optoelectronic applications, offering tunable fluorescence, high biocompatibility, and sustainable synthesis routes. In this review, we explore recent advances in CQD-based fluorescent biosensors, emphasizing their potential in real-time pollutant detection, bioimaging, and green energy solutions. We analyze the underlying photophysical mechanisms, including quantum confinement, surface functionalization, and heteroatom doping, that govern fluorescence modulation. Importantly, the review highlights eco-friendly synthesis techniques and the integration of CQDs in optoelectronic architectures such as photodetectors, photocatalytic systems, and hybrid sensors. By coupling photonic and electronic responses within a single material platform, CQDs offer a pathway toward energy-efficient, neuromorphic-inspired sensing and processing. We conclude by identifying future directions for enhancing the multifunctionality, spectral selectivity, and device-level integration of CQDs, positioning them as sustainable alternatives in two-dimensional (2D) optoelectronic systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The growing demand for real-time, cost-effective, and sustainable technologies to monitor environmental pollutants and biological analytes reflects critical societal challenges in public health, water safety, and disease diagnostics1. Traditional analytical methods, although reliable, are often limited by their complexity, high cost, and lack of portability2. CQDs based fluorescent biosensors have emerged as an efficient alternative, offering high sensitivity, rapid detection, and the potential for miniaturization3. CQDs are nanostructures with distinctive properties that have been vastly investigated in biosensors and bioimaging4,5. Biosensors have emerged as a valuable complement to traditional analytical methods for detecting pollutants in water, offering benefits such as user-friendly operation, low-cost components, and the ability to perform real-time quantification6. Various types of biomediators and transducers are available, with optical and electrochemical biosensors showing the most significant promise for pollutant detection due to their high sensitivity and specificity7. Advances in fluorescent biosensors focus on label-free operation by leveraging the inherent fluorescence properties of nanomaterials, specific metal ions, and certain biological processes8. The application of CQDs in biosensing has demonstrated significant potential due to their ability to interact with biomolecules at the interface. This interaction allows for the design of highly sensitive and selective biosensors for a wide range of biological analytes, including proteins, DNA, and microRNA9. CQDs have been utilized in selective enzyme activity assays and for the fluorescent identification of cancer cells and bacteria, demonstrating their versatility and effectiveness in biomedical applications10,11. The tunable optical properties of CQDs make them highly suitable for real-time monitoring and imaging in biological systems, thereby enabling advancements in diagnostics and personalized medicine.

Detecting environmental pollutants is another key area where CQDs have shown significant promise. Sensors based on CQDs have been developed to detect toxic pollutants, such as heavy metals and phenols, which are vital for protecting environmental and human health12,13. A compact electrochemical biosensor using graphene oxide quantum dots and carboxylated carbon nanotubes demonstrated greater sensitivity compared to traditional methods14. Incorporating CQDs with other nanomaterials, such as graphene quantum dots, enhances solubility and electronic properties15,16, making them ideal for advanced biosensors17. Such hybrid systems significantly improve detection capabilities in environmental monitoring18. Therefore, CQDs-based sensor technologies represent substantial progress in detecting environmental pollutants, due to their enhanced sensitivity and portability.

Besides their prominent role in biosensing, CQDs have found versatile applications in advanced technologies. They are widely explored in green energy generation, such as in solar cells and photo-catalysis, due to their excellent light-harvesting properties19. Additionally, CQDs are utilized in photonics and optoelectronic devices, including light-emitting diodes, lasers, and photodetectors, owing to their tunable fluorescence, high quantum yield, and excellent photostability20. Despite numerous published reviews on CQDs for biosensing, most focus narrowly on either synthesis or specific application areas. This review focuses on current advances in fluorescent biosensors based on CQDs, highlighting pollutant detection, fluorescence mechanisms, tuning strategies, and the enhanced sensitivity of these sensors. It also explores emerging applications in biosensing, solar energy harvesting, photo-catalysis for green energy, and optoelectronic devices.

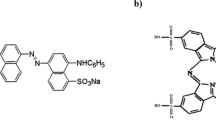

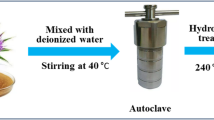

Sustainable approaches to green chemistry

The rising demand for environmental conservation highlights the imperative of utilizing renewable components in the synthesis of CQDs. This tendency highlights the importance of exploring straightforward, eco-friendly, and biological approaches over conventional chemical procedures21. The sustainable synthesis of CQDs offers numerous benefits, including enhanced biocompatibility, stability, scalability, and sustainability22. Green synthesis methods, such as hydrothermal, microwave-assisted, and pyrolysis processes, align with sustainability objectives by minimizing the use of harmful chemicals, energy expenditure, and waste production23. Compared with conventional chemical approaches, these green routes generally demonstrate lower energy consumption, reduced carbon footprint, and the use of safer solvents, while also improving atom economy and reproducibility. By adopting such methodologies, the production of CQDs aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Action), as illustrated in Fig. 1. Their synthesis adheres to the principles of green chemistry, promoting environmental sustainability by transforming waste into valuable nanomaterials24. Sewage sludge, a significant form of urban waste, presents considerable disposal challenges. Utilization of a green chemical methodology to synthesize CQDs from sewage sludge, leveraging its intrinsic carbon content25. This method provides a sustainable pathway for waste valorization and the manufacturing of green nanomaterials.

Scaling up green synthesis of CQDs remains constrained by variability in biomass precursors, poor reproducibility of batch processes, and resource-intensive purification that limits yield. Controlled heteroatom doping is difficult with natural feedstocks, while energy throughput trade-offs challenge sustainability26. Addressing these barriers requires standardized, continuous, and economically viable manufacturing strategies.

Mechanism and characteristics of fluorescence of CQDs

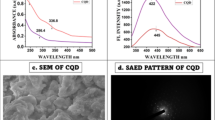

Among the diverse photoluminescence pathways of CQDs, several mechanisms are particularly relevant for practical sensing. Surface-state emission is the most widely exploited, as adsorption or coordination of analytes modulates trap-state energies, producing pronounced fluorescence quenching or enhancement that underpins “turn-off” and “turn-on” sensing modes27. Molecular fluorophore emission, originating from organic species formed during carbonization, also plays an important role, as these centers often display specific binding affinities that enable selective detection of biomolecules and small ions. Energy-transfer processes, notably Forster resonance energy transfer (FRET) and the inner filter effect (IFE), provide high sensitivity and ratiometric readouts by converting analyte-induced spectral overlap into quantifiable signals28. By contrast, core-state emission driven by quantum confinement primarily tunes the emission window rather than directly transducing analyte interactions, limiting its sensing relevance. Nevertheless, quantum confinement and π-conjugated domain states remain central to defining the intrinsic optical properties of CQDs. When particle dimensions fall below the exciton Bohr radius, confinement generates discrete energy states and size-tunable emission, whereas extended π-domains narrow the band gap, yielding red-shifted emission, while smaller domains produce blue-shifted output29.

Taken together, practical sensing applications predominantly rely on surface states, molecular fluorophores, and energy-transfer mechanisms for analyte-dependent modulation, while quantum confinement and π-domains chiefly govern the baseline optical framework that enables spectral tuning for device integration.

Quantum confinement and fluorescent

Fluorescence is a radiative relaxation process in which a substance emits photons following electronic excitation by incident light of sufficient energy. Specifically, lower-wavelength absorption (higher energy) excites electrons; upon returning to their ground state, these electrons emit light of a longer wavelength (lower energy)30. The fluorescence of a substance is typically represented by the Jablonski diagram, which depicts its absorption and emission processes (Fig. 2a)31. During photoexcitation, electrons are promoted from the ground singlet state (S₀) to higher vibrational levels of an excited singlet state (S₂). These carriers rapidly relax to the lowest vibrational level of the first excited singlet state (S₁) through a non-radiative process termed internal conversion. Radiative relaxation from S₁ to S₀ yields fluorescence, characterized by emission at longer wavelengths than the absorbed excitation. In parallel, non-radiative intersystem crossing may channel electrons from S₁ into the triplet manifold (T₁), enabling delayed emission (phosphorescence) via the T₁ → S₀ transition32. Additionally, FRET can occur when the emission energy of one fluorophore excites a neighboring fluorophore, allowing for energy transfer over short distances.

FRET is a specific instance of Resonance Energy Transfer (RET), a phenomenon governed by dipole-dipole interactions33. FRET was first described in 1950 and has since become a widely favored technique for optical sensing due to its high sensitivity and rapid response34. FRET is a non-radiative energy transfer process that typically occurs between two fluorophores separated by the Forster distance, approximately 10 nm35. It involves an energy transfer from a donor in an excited state to a nearby acceptor through dipole-dipole interactions36. For FRET to occur, several conditions must be met—the donor and acceptor must be in proximity, their dipole moments must be oriented favorably, and there must be significant spectral overlap between the donor’s emission and the acceptor’s absorption. Additionally, the donor must have a sufficiently long emission lifetime to allow the transfer (Fig. 2b)37.

Most fluorescent biosensors utilizing nanostructures, either as emitters or acceptors, operate by inducing or inhibiting quenching in response to the target analyte38. These sensors can function in a “Turn-off” mode, where the analyte’s presence causes quenching, or in a “Turn-on” mode, where the system is initially quenched, and fluorescence is selectively restored in the presence of a potent reducing agent (Fig. 2c)39.

Influence of conjugated π-domains on fluorescence

The modulation of color emission in CQDs has consistently been a focal point of interest. By precisely manipulating the structural configuration of CQDs during fabrication, researchers can uncover the underlying mechanisms governing their photoluminescence behavior, which in turn enables control over their optical performance40. The carbonaceous core and surrounding functional groups primarily influence the optical properties of CQDs41. Specifically, when π-conjugated systems are present along with a minimal amount of surface functionalities, the optical response becomes more pronounced. In such cases, the π-conjugated domains play a crucial role, with their band structures serving as the primary emission centers of the carbon-based core42. Adjusting the dimensions and delocalization of these π-electron systems offers a practical means of modifying the emission characteristics of CQDs. The mechanism involving surface imperfections also affects emission behavior, as defect-related chemical groups introduce trap states, contributing to diverse emission levels43. An increased level of surface oxidation may result in a greater number of surface defects and a redshift in emission wavelengths44. The molecular states mechanism involves a fluorescence center comprised of organic fluorophores generated through the carbonization of small molecules45. These fluorophores can become embedded within or attached to the surface of the carbon matrix, significantly affecting their emission behavior. Moreover, heteroatom doping is widely employed as a strategy to modulate fluorescence, quantum efficiency, and photostability of CQDs46.

A key characteristic of CQDs is the quantum confinement effect, which becomes prominent when their size is smaller than the exciton Bohr radius47. This quantum effect results in discrete electronic states due to the transition from continuous valence and conduction bands, and an associated widening of the band gap as the material scales down to the nanoscale. The quantum effect leads to a band gap transition within the ultraviolet-visible spectrum, significantly enhancing the fluorescent quantum yield48,49. In CQDs rich in π-conjugated domains with limited surface functionalities, photoluminescence is primarily attributed to the quantum confinement effect of delocalized π-electrons. In these cases, the conjugated π-domains’ band gap is considered the fluorescence center associated with the carbon core states, as shown in Fig. 3a50. A larger conjugated π-domain in CQDs corresponds to a smaller band gap and a redshifted emission peak. When these domains become large enough, they allow electrons from the valence band to directly transition into conduction band states, bypassing intermediate energy levels and resulting in direct radiative recombination51. Transition of electrons from the valence band to the conduction band yields strong fluorescence arising from recombined electron-hole pairs.

In CQDs, the π-electron systems are often integrated within sp²-hybridized carbon networks. The optical behavior of these networks is influenced by the electronic structure of the bonding and antibonding π orbitals in sp² clusters, which is further modulated by the σ and σ* orbitals of the surrounding lattice52. This interaction facilitates radiative transitions of excitonic electron-hole pairs, thereby enhancing fluorescence. By modulating the size of the π-conjugated domains, the band gap and hence the emission wavelength can be precisely adjusted53. The dimensions of these domains can be modified by employing different solvents and synthetic conditions. For example, Tian et al. developed a method for preparing multi-color CQDs using citric acid and urea as carbon sources, with solvents such as water, glycerol, and dimethylformamide to influence emission properties (Fig. 3b). Additionally, red- and green-emitting CQDs phosphors were deposited on blue-emitting indium-gallium-nitride chips to fabricate white-light-emitting diodes (WLEDs)54.

Influence of structural and pH factors on CQDs photoluminescence

Hydrothermal and microwave synthesis are essential techniques for controlling the size of CQDs, which directly influence their photoluminescence. In hydrothermal synthesis, elevated temperatures or prolonged durations increase the size of CQDs, resulting in a shift of emission from blue to red due to quantum confinement effects55. Microwave-assisted synthesis enables the rapid production of size-tunable CQDs by adjusting the reaction time, with larger dots exhibiting enhanced photoluminescence due to a greater number of emission sites56. Nonetheless, repeatability remains problematic due to fluctuations in reaction parameters and surface chemistry57. The fluorescence intensity of CQDs can also be significantly enhanced through surface functionalization and heteroatom doping (Fig. 4a). In unmodified CQDs, fluorescence arises from direct transitions between the core Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) and Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO) levels (Fig. 4b)58.

The process of surface functionalization and passivation substantially influences the absorbance and photoluminescence characteristics of CQDs59. Surface passivation using ligands such as Polyethylene glycol, amines, and thiols improves photoluminescence by mitigating surface imperfections and altering trap states. These ligands enhance emission by diminishing non-radiative recombination and augment solubility and biocompatibility, which are essential for biomedical applications. Polyethyleneglycolated CQDs exhibit enhanced quantum yield and excitation-dependent photoluminescence while demonstrating decreased cytotoxicity60. Polyethylene glycol is a neutral, biocompatible, and biodegradable macromolecule suitable for medical applications. Polyethylene glycol can inhibit non-specific protein binding, hence limiting the probability of an immunological response61. Polyethyleneimine, a cationic macromolecule, confers a positive charge to CQDs, facilitating their interaction with negatively charged proteins in cell membranes. Positively charged CQDs influence the integrity of the cell membrane, hence enhancing cell transfection. Moreover, positively charged functional groups such as polyethyleneimine are effective in facilitating the binding of DNA and RNA to CQDs62,63.

Doping CQDs with heteroatoms, such as N, P, B, and S elements, which neighbor carbon in the periodic table, effectively tailors their electronic structure, enabling tunable emission, improved quantum yield, and excitation-independent fluorescence for diverse applications64. Nitrogen doping enhances fluorescence by incorporating functional groups and polyaromatic structures, thereby facilitating radiative recombination and increasing the quantum yield65. Nitrogen atoms modify the electronic configuration, enabling tunable emission across the visible spectrum, enhancing photostability, and increasing sensitivity in detecting ions like Fe³⁺ and Hg²⁺ 66.

Sulfur doping also plays a remarkable role in enhancing the quantum yield and fluorescence of CQDs by creating defect states that trap excitons and suppress non-radiative losses67. Due to sulfur’s versatile oxidation states, it can finely tune the band gap of CQDs, boosting their ability to absorb and emit photons efficiently68. Moreover, sulfur-containing functional groups improve surface passivation, increase solubility, and offer selective binding capabilities. The exceptional electrical characteristics of sulfur-doped CQDs with conjugated π structures may enhance their fluorescence properties, perhaps benefiting photodegradation activity69.

Phosphorus doping is an effective strategy for fine-tuning the fluorescence properties of CQDs by creating localized energy levels within the band gap, which favor radiative recombination and enable emission at longer wavelengths70. Being a pentavalent element, phosphorus donates extra electrons to the carbon structure, altering its electronic configuration and boosting its luminescent efficiency71. Additionally, phosphorus-based functional groups enhance biocompatibility, solubility, and responsiveness to specific analytes, rendering phosphorus-doped CQDs suitable for biosensing and imaging applications12.

Going further, combining two or more dopants—such as nitrogen and sulfur or nitrogen and phosphorus—generates synergistic effects that adjust emission wavelengths, increase quantum yield, and enhance photostability72,73. These co-doped CQDs often exhibit multi-color fluorescence, making them ideal for use in optoelectronics, solid-state lighting, and detailed biological imaging74. Overall, heteroatom doping significantly modifies both the structure and optical behavior of CQDs. It allows for emission that is independent of the excitation wavelength, improves light emission efficiency, and enables control over fluorescence color, thereby broadening the applications of these materials in environmental monitoring, sensing, and imaging across a wide range of fields.

The photoluminescence of CQDs is significantly influenced by varying pH levels75. Variations in pH can modify the surface functional groups and protonation states of CQDs, thus influencing their emission strength and wavelength. At reduced pH levels, heightened protonation may result in fluorescence quenching, whereas at elevated pH, deprotonation might augment photoluminescence by diminishing non-radiative recombination pathways.

The influence of pH on the optical characteristics and bandgap of CQDs with a focus on UV-Vis absorption and Tauc plot analyses. The UV-Vis spectra exhibit increased absorbance at 225 nm and 280 nm under acidic conditions (pH 2.00), corresponding to π → π* and n→π* transitions, respectively. As the pH rises, the absorbance intensity declines, indicating alterations in surface chemistry resulting from deprotonation. CQDs produced at acidic pH demonstrate a significantly reduced bandgap ( ~ 3.80 eV), whereas those synthesized at neutral to alkaline pH (7.00–10.00) display slightly elevated values of ( ~ 3.82 eV)76. This change indicates that protonation in acidic circumstances promotes surface passivation, thereby boosting photoluminescence, while deprotonation at elevated pH diminishes emission efficiency. The pH markedly affects the electrical structure and luminous properties of CQDs, highlighting its significance in optimizing their efficacy for sensing and imaging applications. Liu et al. investigated the performance of a pH-regulated fluorescence sensor array designed using cetylpyridinium chloride CQDs and a chelating agent in an indicator–spacer–receptor (ISR) configuration. By modulating the pH 7.4 and 8.8, the system enhances the sensitivity and selectivity toward heavy metal ions77. The stability and fluorescence properties of nitrogen-doped CQDs were assessed under varying pH conditions to optimize their sensitivity and selectivity for detecting Cr6+ and Mn7+. Native nitrogen-doped CQDs exhibit strong fluorescence, especially between pH 3 and 7, indicating high stability and optimal emission. Upon exposure to Cr⁶⁺ and Mn⁷⁺, the fluorescence is significantly quenched at all pH levels. The quenching effect is more pronounced with Cr⁶⁺, suggesting stronger interaction or energy transfer with the nitrogen-doped CQDs. Mn⁷⁺ causes moderate yet evident fluorescence suppression. These findings demonstrate the potential of nitrogen-doped CQDs as sensitive fluorescent probes for detecting Cr⁶⁺ and Mn⁷⁺ across a wide pH range, making them suitable for environmental sensing75.

Emerging applications of CQDs

CQDs have progressed beyond their initial role in biosensing to become versatile nanomaterials with applications spanning biomedical sciences, energy production, environmental monitoring, photonics, and catalysis. Their unique attributes, including chemical stability, tunable photoluminescence, biocompatibility, and ease of synthesis facilitate their adoption in diverse fields. As new strategies emerge to exploit their structural and electronic properties, CQDs are increasingly employed to address pressing global challenges.

Environmental monitoring and remediation

The distinctive optical and surface properties of CQDs make them highly effective in environmental applications, where they function both as photocatalysts and as sensitive probes for pollutant detection. As photocatalysts, CQDs and their composites achieve remarkable degradation efficiencies, often exceeding 90% for dyes, antibiotics, and pesticides in water78. For example, a green-synthesized ZnO–CQDs photocatalyst derived from plant waste completely degraded Malachite Green and Methylene Blue within 60 min under solar light, attributed to enhanced charge separation and radical involvement79. Similarly, Zn phthalocyanine/nitrogen-doped CQDs hybrids demonstrated significant dye removal efficiency even in the absence of light80. Beyond degradation, CQDs derived from cellulose and carboxymethyl cellulose achieved efficient Cr(VI) adsorption, with thermally fabricated CQDs exhibiting faster kinetics81. CQDs synthesized from wolfberry straw via optimized green methods showed a Cu²⁺ adsorption capacity of 68.06 mg g−182. Composite membranes combining sulfonated polyether ether ketone (SPEEK) with red CQDs effectively detect and remove Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺ from water. Composite membranes integrating sulfonated polyether ether ketone (SPEEK) with red CQDs not only removed Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺ with 100% efficiency but also provided fluorescence-based detection, with facile regeneration using NaCl83. Likewise, a CQDs/LDH composite displayed rapid Cd(II) adsorption with capacities up to 12.60 mg/g84. Table 1 summarizes the various carbon quantum dot-based probes used in environmental remediation.

CQDs serve as sustainable probes for pollutant detection due to their tunable emission and strong fluorescence quenching responses. Red-emitting CQDs synthesized via solvothermal treatment enabled ultrasensitive pesticide detection through a ratiometric fluorescence platform85. FRET-based sensors coupling nitrogen-doped CQDs with gold nanoparticles achieved pg L−1 sensitivity for organophosphorus pesticides86. For heavy metal monitoring, CQDs functionalized with lysine or polyethyleneimine provided selective Cu2+ detection with limits as low as 6 nM, validated in real water samples87,88. Ion-imprinted CQDs grafted onto mesoporous silica demonstrated high selectivity for Cu2+ with excellent recovery rates in complex matrices89. In addition, CQDs-based thin films enabled rapid, accurate detection of multiple heavy metals (Pb, Ni, Mn, Co, Cr) within one minute90. Eco-friendly CQDs synthesized from fish scale waste combined photocatalytic activity (dye degradation >96%) with selective Cd2+ sensing91. Nitrogen-doped CQDs derived from Alstonia scholaris leaves further extended pollutant sensing to Cr6+ and Mn7+ via FRET-based mechanisms75. Table 2 summarizes key parameters such as limit of detection (LOD), linear ranges, and selectivity of CQDs.

Applications in biomolecule detection

CQDs are a growing class of carbon-based nanomaterials that are gaining attention for their applications in biosensing, bioimaging, and the delivery of drugs or genes. Typically, under 10 nm and spherical, these zero-dimensional (0D) nanoparticles possess distinctive chemical, optical, and electronic properties, making them highly adaptable for sensing biomolecules (Table 3)92. A biocompatible FRET-based biosensor for HIV DNA detection using CQDs and gold nanoparticles. CQDs synthesized from histidine were functionalized with capture probes, while CQDs and gold nanoparticles acted as quenchers. Target DNA triggered fluorescence recovery by displacing CQDs from the surface of gold nanoparticles. The biosensor showed excellent specificity, a detection limit of 15 fM, and effective performance in human serum, demonstrating strong potential for detecting various DNA biomarkers93. Hydrothermal synthesis of CQDs using dried beet powder as a natural carbon source, without extra chemicals or modifications. The resulting CQDs are 4–8 nm quasi-spherical nanoparticles featuring carboxyl and hydroxyl surface groups. They exhibit strong fluorescence, high water solubility, and good biocompatibility. Notably, amoxicillin enhances their fluorescence intensity, showing a clear linear relationship with amoxicillin concentration94. One-step solid-phase synthesis of colistin-modified fluorescent CQDs for selective detection of Escherichia coli. The colistin-modified fluorescent CQDs exhibited detection limits of 460 cfu/mL for Escherichia coli, characterized by strong water dispersibility, a size of 2–5 nm, and a quantum yield of 7.56%. Practical detection was validated in urine, juice, and tap water95. Fluorescence-based strategy for detecting hematin using CQDs synthesized from p-aminobenzoic acid and ethanol. The sensor relies on the inner filter effect, where hematin selectively quenches the fluorescence of CQDs. A strong linear response was observed over the range of 0.5–10 μM, with a detection limit of 0.25 μM. Successfully tested in human red cells, the assay shows promising potential for hematin detection in complex biological environments96.

Doping CQDs with nitrogen and sulfur enhances luminescence, enabling highly selective acetone detection with a low detection limit of 7.2 × 10−7 M. The probe showed excellent performance in human blood and urine. Featuring a high quantum yield (69.27%), water dispersibility, non-toxicity, and strong photostability, it offers a promising, cost-effective alternative for ketone detection in clinical diagnostics97. A label-free fluorescent aptasensor for detecting kanamycin using gold nanoparticles to quench CQDs via the inner filter effect. Kanamycin binds specifically to Ky2 aptamers (a synthetic single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotide), causing gold nanoparticles to aggregate in the presence of high salt, thereby disrupting the inner filter effect and restoring fluorescence. The sensor detects kanamycin linearly in the range of 0.04–0.24 μM, with a detection limit of 18 nM, and exhibits strong performance in milk samples, indicating its promise for food safety applications98. Boronic acid-modified CQDs for nonenzymatic blood glucose sensing. Using phenylboronic acid as the sole precursor, the approach simplifies fabrication while enabling selective fluorescence quenching by glucose. The sensor demonstrates high sensitivity (9–900 μM), excellent selectivity, and successful serum application99,100.

Advanced imaging and theranostics

CQDs have emerged as highly promising nanomaterials for advanced biomedical imaging and theranostic applications due to their unique optical properties, excellent biocompatibility, and facile surface modification99. In advanced imaging, CQDs serve as effective fluorescent probes for cellular and molecular visualization, enabling high-resolution imaging of biological structures and dynamic processes101. Theranostics, a fusion of therapy and diagnostics, benefits significantly from the multifunctional platform of CQDs. CQDs can be engineered to co-deliver drugs and imaging agents, facilitating real-time monitoring of drug delivery and therapeutic response102. A rapid, chemical-free toasting method using bread slices produced CQDs in just 2 hours, much faster than the 10-hour hydrothermal process. These CQDs effectively bioimaged murine colon carcinoma (CT-26) and human colorectal adenocarcinoma (HT-29) colon cancer cells, showing fluorescence comparable to that from conventional synthesis103. Walnut oil-derived CQDs, with a quantum yield of 14.5%, exhibited strong fluorescence and stability. Tested on human prostate cancer (PC3), human breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7), and HT-29 cancer cells, they exhibited notable cytotoxicity, especially against MCF-7 and PC3. Apoptosis was confirmed via caspase-3 activation, though caspase-9 and mitochondrial membrane potential remained unaffected. Cellular uptake was visualized using fluorescence microscopy104. Nitrogen-doped CQDs synthesized from citrus lemon showed strong blue fluorescence, excellent water solubility, and high quantum yield ( ~ 31%). With an average size of 3 nm, they selectively detected Hg²⁺ ions with high sensitivity, with a LOD of 5.3 nM. Nitrogen-doped CQDs exhibited low cytotoxicity (cell viability > 88% in MCF7 cells) and enabled successful multi-color live-cell imaging due to their biocompatibility105.

Cadmium-free QDs have advanced, drawing attention in the emerging diagnostic and therapeutic (theranostic) applications of quantum dots in regenerative medicine, oncology, and infectious disease management106. Breast cancer remains a leading malignancy among women worldwide. Despite therapeutic advances, early diagnosis and effective targeted treatments remain challenging. Recently, CQDs, a type of fluorescent carbon-based nanomaterial, have shown promise as multifunctional theranostic agents. CQDs’ applications in Breast cancer for targeted drug delivery, imaging, photothermal and photodynamic therapies, and biosensing, while discussing advancements in their synthesis and biofunctionalization107. CQDs and chromium-doped alumina exhibited potent reactive oxygen species generation, strong photodynamic antibacterial effects up to 95% biofilm inhibition, and enhanced anti-cancer activity against CT-26 cells, particularly under UVA light108. CQDs enable precise tumor targeting, while their ability to produce reactive oxygen species supports photodynamic therapy. CQDs also serve as drug carriers and biosensors for biomarker detection109. Advancing innovative strategies is essential for the early diagnosis and treatment of neurological disorders.

The blood-brain barrier poses a significant challenge to drug delivery to the central nervous system. CQDs, due to their biocompatibility and nanoscale size, have emerged as promising nanocarriers capable of traversing the blood-brain barrier for efficient neurotherapeutic applications110. Caffeic acid-derived CQDs demonstrate neuroprotective potential against pesticide-induced Parkinson’s pathology. They inhibit amyloid aggregation of hen egg white lysozyme (HEWL), scavenge free radicals via sp²-rich domains, and exhibit negligible cytotoxicity up to 5 mg/mL in human neuroblastoma (SH-SY5Y) cells. Caffeic acid-CQDs protect against paraquat-induced oxidative stress, offering promise as blood-brain barrier-penetrating nanotherapeutics111. CQDs, owing to their eco-friendly origin, aqueous solubility, and enhanced biocompatibility, exhibit superior quantum yields and optical properties, making them highly suitable for bioimaging and targeted drug delivery112. Large amino acid mimicking (LAAM) CQDs, featuring amino acid-like surface groups, interact with L-type amino acid transporter-1, enabling targeted tumor imaging and chemotherapy delivery, and offering precise, stimuli-responsive drug release for cancer treatment113.

The high biocompatibility, tunable photoluminescence, and versatile surface chemistry of CQDs support their use across multiple imaging modalities, including tumor visualization, infection tracking, and photoacoustic diagnostics within emerging theranostic platforms. However, key challenges remain, particularly limited deep-tissue imaging capacity, variable synthesis reproducibility, and incomplete toxicity and biodistribution profiles as illustrated in Fig. 5.

CQDs for green energy production

CQDs have gained significant attention as sustainable nanomaterials for green energy applications. Photocatalytic water splitting using sunlight offers a sustainable and clean alternative to fossil fuels for hydrogen production. The process requires a photocatalyst with a suitable band gap (≥1.23 eV) to drive the redox reactions, H₂ evolution, and O₂ evolution114. Mehta et al. investigated visible-light and sunlight-driven water splitting using Gold-CQDs as shown in Fig. 6a, where CQDs absorb light and excite electrons from HOMO to LUMO (2.78 eV). Gold enhances surface plasmon resonance, boosting charge separation and hydrogen generation in a sealed aqueous system115. Titanium dioxide is a benchmark photocatalyst, but its activity is limited to UV light. CQDs, with their tunable band gaps, up- and down-conversion photoluminescence, and superior electron transfer properties, enable the harvesting of visible and near-infrared light116.

a hydrogen production through plasmonic photocatalysis, reproduced with permission from ref. 115, copyright (Elsevier, 2019)115. b CQDs–microbe biohybrid system promoting enhanced bio-hydrogen production, reproduced with permission from ref. 118, copyright (Elsevier, 2024)118. c Energy band alignment of TiO₂ coupled with N-doped CQDs to improve photocatalytic H₂ evolution, reproduced with permission from ref. 90, copyright (Elsevier, 2021)90. d The heat map displays absolute H₂ production rates for each material both with and without CQDs.

CQDs function as efficient, low-cost, and scalable photosensitizers for solar-driven hydrogen production. In combination with a Ni-bis(diphosphine) molecular catalyst, CQDs demonstrated high hydrogen evolution activity (398 μmolH₂g−1h−1) and a quantum efficiency of 1.4%, showing remarkable performance under visible light and full-spectrum solar irradiation117. Additionally, surface-doped CQDs, especially nitrogen-doped variants, enhance microbial fermentation and biohydrogen production by facilitating electron transfer and optimizing metabolic pathways in Lactobacillus delbrueckii (Fig. 6b)118. As hydrogen is considered a clean energy carrier, reducing reliance on fossil fuel-based production is essential. CQDs offer innovative solutions for generating green hydrogen through renewable and low-impact pathways119. Their superior light absorption, low recombination of photogenerated carriers, and abundant surface-active sites make CQDs promising photocatalysts, despite current efficiency limitations120. The nitrogen-doped CQDs system synergistically utilizes UV light via titanium dioxide and visible light via nitrogen-doped CQDs. Nitrogen-doped CQDs extend the photoresponse range and enhance charge separation and transfer efficiency, resulting in improved photocatalytic hydrogen production (Fig. 6c). The reduced electron-hole recombination and dual-band light harvesting (UV and visible) make this composite a promising material for solar-to-hydrogen energy conversion90.

A range of CQD-based photocatalytic systems exhibit markedly enhanced hydrogen evolution performance compared with their individual components. For instance, CQDs supported on covalent triazine frameworks (CTF) at 0.24% loading generate 102 μmol g−1 h−1, outperforming the 34.5 μmol g−1 h−1 of the bare material121. Similarly, CQDs integrated with g-C₃N₄ (CCN) achieve 1291 μmol g−1 h−1 in RhB solution compared with 664 μmol g−1 h−1 for pristine g-C₃N₄122. Metal-free CQDs/PFTBTA polymer dots show a substantial rise in activity, delivering 10,750 μmol g−1 over 6 h, whereas PFTBTA alone yields only 2400 μmol g−1123. CQDs coupled with CdInS (CIS-3) demonstrate 956.8 μmol g−1 h−1 relative to 126.4 μmol g−1 h−1 for CdInS alone124. In another composite, MoC quantum dots embedded within N-doped carbon/g-C₃N₄ produce 1709 μmol g−1 h−1, far surpassing the 8 μmol g−1 h−1 of unmodified g-C₃N₄125. ZCS QDs combined with K-doped g-C₃N₄ reach 9610 μmol g−1 h−1, compared with 3210 μmol g−1 h−1 for ZCS QDs alone and only 0.61 μmol g−1 h−1 for K-CN126. Likewise, CIZS QDs hybridized with MoS₂ and CQDs exhibit an enhanced output of 3706 μmol g−1 h−1, significantly higher than the 557 μmol g−1 h−1 of CIZS QDs alone127. Overall, these results reveal strong synergistic effects of CQDs, leading to a marked enhancement in photocatalytic hydrogen evolution, as quantitatively demonstrated by the elevated hydrogen production rates (μmol g−1 h−1) shown in Fig. 6d.

Green hydrogen production via electrolysis using oilfield-produced water with CQDs enhances Faradaic efficiency from 77% to 83% and mitigates oil interference at low concentrations. The process improves hydrogen yield by 10% and enables sustainable energy generation aligned with net-zero emission goals128. The electrolysis property makes CQDs highly promising for enhancing photocatalytic efficiency by improving charge separation and extending light absorption, thereby advancing the generation of green hydrogen from solar energy. Furthermore, their electroluminescent properties enhance energy storage and conversion in supercapacitors, with tunable color emission under varying currents, attributed to distinct band-gap and surface-defect mechanisms129.

Photonics, optoelectronics, and neuromorphic devices

Quantum dots are nanometer-scale semiconductor particles with unique optical and electrical properties due to quantum confinement. Often referred to as “artificial atoms,” Quantum dots possess discrete energy states and exhibit size-dependent light emission. These characteristics make them valuable in a range of modern technologies, including solar cells, light-emitting diodes, transistors, photodetectors, and biomedical applications130.

CQDs and classical II–VI semiconductor quantum dots (QDs, e.g., CdSe, PbS) both exhibit quantum confinement–mediated, size-tunable photophysical properties, yet they differ fundamentally in composition, electronic structure, and device integration potential. CQDs are nanoscale, carbon-based materials whose luminescence originates from a combination of core states, surface defects, and molecular fluorophores131, whereas II–VI QDs are crystalline semiconductor nanocrystals with well-defined bandgap engineering and excitonic transitions132. Compared with their II–VI counterparts, CQDs offer intrinsic advantages such as low toxicity, facile and often green synthetic routes, excellent aqueous dispersibility, and high photostability, features that render them particularly attractive for bio-integrated photonics and color-conversion platforms133. By contrast, II–VI QDs provide superior charge transport, narrow emission linewidths, and consistently high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQY), which collectively underpin their success in electroluminescent and photodetection applications134. However, classical II–VI QDs are non-biodegradable and relatively expensive, limiting their sustainable deployment135. These limitations are particularly evident in thin-film transistors (TFTs), where silicon and Cd/Pb chalcogenides also encounter scalability and toxicity concerns. In this context, solution-processed and environmentally stable CIS CQDs have emerged as promising, low-cost, and nontoxic alternatives for next-generation flexible electronic devices136.

In terms of device performance, the disparity is evident. CQD-based light-emitting diodes (LEDs) have achieved external quantum efficiencies (EQE) in the single- to low-double-digit range, typically ≈5–10%. Optimized devices exhibit maximum luminance on the order of 10³–10⁴ cd m⁻². Recent advances in thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) and nanostructured CQD architectures offer further potential for performance improvement137. In contrast, II–VI and perovskite QD LEDs routinely report EQEs exceeding 20–25%, alongside luminance values and operational stabilities that already satisfy stringent display requirements. Similarly, while CQD-based photodetectors exhibit modest yet workable metrics, responsivities of ~1.5 × 10⁻³ A W−1 and detectivities up to ~1.8 × 10¹⁰ Jones in solution-processed systems, the performance remains lower than that of PbS- and PbSe-based photodetectors, which routinely achieve detectivities in the 10¹¹–10¹² Jones range with significantly higher responsivities138. Despite limitations, CQDs are increasingly applied in display technologies, particularly for energy-efficient color conversion, where they enhance color vibrancy and reduce energy consumption compared to conventional phosphor-based LCD systems139,140.

Beyond conventional optoelectronics, recent advances have extended CQD functionality into neuromorphic and in-sensor computing paradigms. CQDs can act as active elements in memristive and synaptic devices, exhibiting optoelectronic plasticity that enables hardware-level learning141. For instance, CQDs derived from jaggery embedded in an indigo molecular layer were used to construct an artificial synapse, demonstrating long-term potentiation (LTP), long-term depression (LTD), stable retention, and reproducible weight updates under repeated learning–forgetting–relearning cycles. Comparable mechanisms are observed in II–VI systems, such as CdSe/ZnS QDs in polymer matrices, which exhibit high current switching ratios ( ~ 10⁴) and endurance over hundreds of cycles due to charge trapping or detrapping at QD–polymer interfaces142. In addition, hybrid CQD-based neuromorphic sensors have shown remarkable multifunctionality. For example, CQDs integrated with perovskite phototransistors demonstrate simultaneous light sensing and synaptic learning behaviors. These devices operate with ultralow event energy and exhibit broadband optical response, thereby bridging sensing and memory within a single platform143. Key strategies for future progress include tailoring defect densities to modulate synaptic weights, engineering CQD–hybrid heterostructures to couple stability with optical sensitivity, reducing operating voltages and event energy costs, and validating synaptic behaviors under both electrical and optical stimuli. Device-level integration of CQDs represent promising alternatives to conventional 2D optoelectronic systems, offering enhanced tunability, stability, and multifunctional performance.

Comparative study

Many previous reviews have offered separate overviews of Synthesis, photophysics, or applications of CQDs. This work provides a comprehensive perspective that integrates mechanistic insights with advanced applications. In particular, it details photoluminescence mechanisms and connects them to emerging uses spanning biosensing, pollutant detection, environmental remediation, green energy production, and electronic devices. By linking fundamental principles with technological opportunities, this review not only underscores the current limitations of CQDs but also identifies critical research directions required to advance the field. This review distinguishes itself in five concrete ways:

-

i.

Green-chemistry focus with quantitative sustainability metrics: It evaluates green synthetic routes using quantitative sustainability metrics, including energy demand, atom economy, solvent safety, waste generation, and alignment with UN Sustainable Development Goals, while identifying gaps in life-cycle and techno-economic analyses.

-

ii.

Mechanism-to-application mapping: It links the fluorescence mechanisms most relevant to practical sensing with specific modes such as turn-off, turn-on, FRET, and IFE.

-

iii.

Device and systems perspective with 2D integration: It highlights device-level integration with 2D materials, analyzing how CQDs’ 2D heterostructures influence charge transfer, responsivity, and stability—areas seldom addressed in prior surveys.

-

iv.

Actionable comparative data presentation: It consolidates performance data into comparative tables summarizing quantum yield, detection limits, excitation dependence, stability, and reproducibility, enabling direct benchmarking across studies.

-

v.

Forward-looking strategies for neuromorphic applications: It outlines strategies for CQD-based synaptic devices—defect engineering, hybrid heterostructures, reduced voltages, and validated synaptic behaviors.

Outlook

CQDs have emerged as sustainable and multifunctional nanomaterials distinguished by their tunable photophysical properties, low toxicity, and broad potential in environmental monitoring, biomedicine, energy conversion, and optoelectronics. Despite these advantages, critical challenges remain before CQDs can be translated from laboratory-scale studies to practical technologies. Key challenges include improving the reproducibility of green synthetic routes, achieving scalable production with uniform size and surface chemistry, and establishing precise control over photoluminescence mechanisms. Current synthesis strategies frequently yield heterogeneous products with broad emission profiles, constraining their use in applications that demand narrowband emission, high quantum yields, and predictable device integration. Moreover, although surface functionalization and heteroatom doping have proven powerful for tuning optical performance, these approaches often introduce variability in stability, cytotoxicity, and long-term reliability, underscoring the necessity for a more systematic mechanistic understanding.

In device applications, CQD-based photodetectors, light-emitting diodes, and neuromorphic systems continue to lag behind II–VI and perovskite quantum dots in key metrics such as responsivity, external quantum efficiency, and operational durability. Bridging this performance gap will require rational design of CQD–hybrid heterostructures, deliberate defect engineering to modulate charge transport, and strategies to suppress non-radiative recombination. A further challenge lies in reconciling sustainability with performance: while green synthetic approaches are attractive for minimizing environmental impact, they must advance toward industrial scalability without compromising reproducibility or optoelectronic quality. Equally important is the need for comprehensive long-term toxicity, biocompatibility, and environmental fate assessments to establish CQDs as safe materials for clinical translation and ecological deployment.

Looking forward, progress in the field will depend on integrating green chemistry with precision nanofabrication to produce high-quality, reproducible CQDs at scale. Advanced in situ characterization, coupled with computational modeling, offers a powerful route to elucidate fluorescence mechanisms and guide rational tuning of surface states, defect structures, and π-domain architectures. The successful incorporation of CQDs into multifunctional devices ranging from bio-integrated photonics and hybrid photocatalysts for solar-to-hydrogen energy conversion to neuromorphic sensing platforms will demand interdisciplinary collaboration across chemistry, materials science, physics, and biology. Alignment with global sustainability frameworks, particularly the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, should remain a guiding principle to ensure that advances in CQD science address not only technological frontiers but also societal and environmental priorities. By overcoming these challenges, CQDs may evolve into next-generation nanomaterials that combine efficiency, multifunctionality, safety, and scalability, thereby enabling sustainable pathways for future technologies.

Data availability

The data presented in this review article are derived from previously published studies, which have been cited appropriately throughout the manuscript. Additionally, no third-party materials have been utilized.

References

Huang, C. W. et al. A review of biosensor for environmental monitoring: principle, application, and corresponding achievement of sustainable development goals. Bioengineered 14, 58–80 (2023).

Salouti, M. & Khadivi Derakhshan, F. Biosensors and Nanobiosensors in Environmental Applications. in Biogenic Nano-Particles and their Use in Agro-ecosystems 515–591 (Springer Singapore, Singapore, (2020).

Khan, M. E., Mohammad, A. & Yoon, T. State-of-the-art developments in carbon quantum dots (CQDs): Photo-catalysis, bio-imaging, and bio-sensing applications. Chemosphere 302, 134815 (2022).

Umar, E. et al. A state-of-the-art review on carbon quantum dots: Prospective, advances, zebrafish biocompatibility and bioimaging in vivo and bibliometric analysis. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 35, e00529 (2023).

Ding, C., Zhu, A. & Tian, Y. Functional Surface Engineering of C-Dots for Fluorescent Biosensing and in Vivo Bioimaging. Acc. Chem. Res 47, 20–30 (2014).

Herrera-Dominguez, M. et al. Optical Biosensors and Their Applications for the Detection of Water Pollutants. Biosens. (Basel) 13, 370 (2023).

Lagarde, F. & Jaffrezic-Renault, N. Cell-based electrochemical biosensors for water quality assessment. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 400, 947–964 (2011).

Ozyurt, C., Ustukarci, H., Evran, S. & Telefoncu, A. MerR-fluorescent protein chimera biosensor for fast and sensitive detection of Hg 2+ in drinking water. Biotechnol. Appl Biochem 66, 731–737 (2019).

Walther, B. K. et al. Nanobiosensing with graphene and carbon quantum dots: Recent advances. Mater. Today 39, 23–46 (2020).

Molaei, M. J. Principles, mechanisms, and application of carbon quantum dots in sensors: a review. Anal. Methods 12, 1266–1287 (2020).

Das, R., Bandyopadhyay, R. & Pramanik, P. Carbon quantum dots from natural resource: A review. Mater. Today Chem. 8, 96–109 (2018).

Kalaiyarasan, G., Joseph, J. & Kumar, P. Phosphorus-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots as Fluorometric Probes for Iron Detection. ACS Omega 5, 22278–22288 (2020).

Chu, H. W., Unnikrishnan, B., Anand, A., Lin, Y. W. & Huang, C. C. Carbon quantum dots for the detection of antibiotics and pesticides. J. Food Drug Anal. 28, 540–558 (2020).

Zhu, X., Wu, G., Lu, N., Yuan, X. & Li, B. A miniaturized electrochemical toxicity biosensor based on graphene oxide quantum dots/carboxylated carbon nanotubes for assessment of priority pollutants. J. Hazard Mater. 324, 272–280 (2017).

Nangare, S., Chandankar, S. & Patil, P. Design of carbon and graphene quantum dots based nanotheranostics applications for glioblastoma management: Recent advanced and future prospects. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 89, 105060 (2023).

Zhao, D. L. & Chung, T. S. Applications of carbon quantum dots (CQDs) in membrane technologies: A review. Water Res 147, 43–49 (2018).

Campuzano, S., Yanez-Sedeno, P. & Pingarron, J. M. Carbon Dots and Graphene Quantum Dots in Electrochemical Biosensing. Nanomaterials 9, 634 (2019).

Zheng, X. T., Ananthanarayanan, A., Luo, K. Q. & Chen, P. Glowing Graphene Quantum Dots and Carbon Dots: Properties, Syntheses, and Biological Applications. Small 11, 1620–1636 (2015).

Molaei, M. J. The optical properties and solar energy conversion applications of carbon quantum dots: A review. Sol. Energy 196, 549–566 (2020).

Li, X., Rui, M., Song, J., Shen, Z. & Zeng, H. Carbon and Graphene Quantum Dots for Optoelectronic and Energy Devices: A Review. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 4929–4947 (2015).

Dhariwal, J., Rao, G. K. & Vaya, D. Recent advancements towards the green synthesis of carbon quantum dots as an innovative and eco-friendly solution for metal ion sensing and monitoring. RSC Sustainability 2, 11–36 (2024).

Omran, B. A., Whitehead, K. A. & Baek, K. H. One-pot bioinspired synthesis of fluorescent metal chalcogenide and carbon quantum dots: Applications and potential biotoxicity. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 200, 111578 (2021).

Rana, A., Yadav, K. & Jagadevan, S. A comprehensive review on green synthesis of nature-inspired metal nanoparticles: Mechanism, application and toxicity. J. Clean. Prod. 272, 122880 (2020).

Rawat, P. et al. An overview of synthetic methods and applications of photoluminescence properties of carbon quantum dots. Luminescence 38, 845–866 (2023).

Rossi, B. L. et al. Carbon quantum dots: An environmentally friendly and valued approach to sludge disposal. Front. Chem. 10, 858323 (2022).

Moradialvand, Z., Parseghian, L. & Rajabi, H. R. Green synthesis of quantum dots: Synthetic methods, applications, and toxicity. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 18, 100697 (2025).

Khare, S., Sohal, N., Kaur, M. & Maity, B. Deep eutectic solvent-assisted carbon quantum dots from biomass Triticum aestivum: A fluorescent sensor for nanomolar detection of dual analytes mercury (Ⅱ) and glutathione. Heliyon 11, e41853 (2025).

Zhang, L., Yang, X., Yin, Z. & Sun, L. A review on carbon quantum dots: Synthesis, photoluminescence mechanisms and applications. Luminescence 37, 1612–1638 (2022).

Xu, A. et al. Carbon-Based Quantum Dots with Solid-State Photoluminescent: Mechanism, Implementation, and Application. Small 16, e2004621 (2020).

Gaviria-Arroyave, M. I., Cano, J. B. & Peñuela, G. A. Nanomaterial-based fluorescent biosensors for monitoring environmental pollutants: A critical review. Talanta Open 2, 100006 (2020).

Feng, G., Zhang, G.-Q. & Ding, D. Design of superior phototheranostic agents guided by Jablonski diagrams. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 8179–8234 (2020).

Berezin, M. Y. & Achilefu, S. Fluorescence Lifetime Measurements and Biological Imaging. Chem. Rev. 110, 2641–2684 (2010).

Jones, G. A. & Bradshaw, D. S. Resonance Energy Transfer: From Fundamental Theory to Recent Applications. Front. Phys. 7, 100 (2019).

Panja, S. K. & Fazal, A. D. Fluorescence Spectroscopy. in Functional Fluorescent Materials 1–16 (CRC Press, Boca Raton, (2024).

Bhattacharyya, S. & Ducheyne, P. 3.28 Fluorescence Based Intracellular Probes. in Comprehensive Biomaterials II 606–634 (Elsevier, (2017).

Li, W., Liang, Z., Wang, P. & Ma, Q. The luminescent principle and sensing mechanism of metal-organic framework for bioanalysis and bioimaging. Biosens. Bioelectron. 249, 116008 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer in atomically precise metal nanoclusters by cocrystallization-induced spatial confinement. Nat. Commun. 15, 5351 (2024).

Sargazi, S. et al. Fluorescent-based nanosensors for selective detection of a wide range of biological macromolecules: A comprehensive review. Int J. Biol. Macromol. 206, 115–147 (2022).

Wang, X., Liu, Z., Gao, P., Li, Y. & Qu, X. Quantum dots mediated fluorescent “turn-off-on” sensor for highly sensitive and selective sensing of protein. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 185, 110599 (2020).

Miao, X. et al. Synthesis of Carbon Dots with Multiple Color Emission by Controlled Graphitization and Surface Functionalization. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704740 (2018).

Barman, M. K. & Patra, A. Current status and prospects on chemical structure driven photoluminescence behaviour of carbon dots. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C: Photochemistry Rev. 37, 1–22 (2018).

Shamsipur, M., Barati, A., Taherpour, A. A. & Jamshidi, M. Resolving the Multiple Emission Centers in Carbon Dots: From Fluorophore Molecular States to Aromatic Domain States and Carbon-Core States. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 4189–4198 (2018).

Emeline, A. V., Kataeva, G. V., Ryabchuk, V. K. & Serpone, N. Photostimulated Generation of Defects and Surface Reactions on a Series of Wide Band Gap Metal-Oxide Solids. J. Phys. Chem. B 103, 9190–9199 (1999).

Zhang, C. & Lin, J. Defect-related luminescent materials: synthesis, emission properties and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 7938 (2012).

Kasprzyk, W., Swiergosz, T., Romanczyk, P. P., Feldmann, J. & Stolarczyk, J. K. The role of molecular fluorophores in the photoluminescence of carbon dots derived from citric acid: current state-of-the-art and future perspectives. Nanoscale 14, 14368–14384 (2022).

Alafeef, M., Srivastava, I., Aditya, T. & Pan, D. Carbon Dots: From Synthesis to Unraveling the Fluorescence Mechanism. Small 20, 2303937 (2024).

Yoffe, A. D. Semiconductor quantum dots and related systems: Electronic, optical, luminescence and related properties of low dimensional systems. Adv. Phys. 50, 1–208 (2001).

Yang, T. Q. et al. Origin of the Photoluminescence of Metal Nanoclusters: From Metal-Centered Emission to Ligand-Centered Emission. Nanomaterials 10, 261 (2020).

Kharangarh, P. R., Umapathy, S. & Singh, G. Effect of defects on quantum yield in blue emitting photoluminescent nitrogen doped graphene quantum dots. J. Appl. Phys. 122, 145107 (2017).

Latha, B. D. et al. Fluorescent carbon quantum dots for effective tumor diagnosis: A comprehensive review. Biomed. Eng. Adv. 5, 100072 (2023).

Hallaji, Z., Bagheri, Z., Kalji, S.-O., Ermis, E. & Ranjbar, B. Recent advances in the rational synthesis of red-emissive carbon dots for nanomedicine applications: A review. FlatChem 29, 100271 (2021).

Ding, H. et al. Surface states of carbon dots and their influences on luminescence. J. Appl. Phys. 127, 231101 (2020).

Gan, J. et al. Lignocellulosic Biomass-Based Carbon Dots: Synthesis Processes, Properties, and Applications. Small 19, 2304066 (2023).

Tian, Z. et al. Full-Color Inorganic Carbon Dot Phosphors for White-Light-Emitting Diodes. Adv. Opt. Mater. 5, 1700416 (2017).

Sarkar, S., Banerjee, D., Ghorai, U. K., Das, N. S. & Chattopadhyay, K. K. Size dependent photoluminescence property of hydrothermally synthesized crystalline carbon quantum dots. J. Lumin 178, 314–323 (2016).

Yoshinaga, T., Iso, Y. & Isobe, T. Particulate, Structural, and Optical Properties of D-Glucose-Derived Carbon Dots Synthesized by Microwave-Assisted Hydrothermal Treatment. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 7, R3034–R3039 (2018).

Seven, E. S. et al. Hydrothermal vs microwave nanoarchitechtonics of carbon dots significantly affects the structure, physicochemical properties, and anti-cancer activity against a specific neuroblastoma cell line. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 630, 306–321 (2023).

Yang, H.-L. et al. Carbon quantum dots: Preparation, optical properties, and biomedical applications. Mater. Today Adv. 18, 100376 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Preparation of carbon quantum dots with tunable photoluminescence by rapid laser passivation in ordinary organic solvents. Chem. Commun. 47, 932–934 (2011).

Yang, X. et al. Photoluminescent carbon dots synthesized by microwave treatment for selective image of cancer cells. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 456, 1–6 (2015).

D’souza, A. A. & Shegokar, R. Polyethylene glycol (PEG): a versatile polymer for pharmaceutical applications. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 13, 1257–1275 (2016).

Sun, Y. et al. Development of a biomimetic DNA delivery system by encapsulating polyethyleneimine functionalized silicon quantum dots with cell membranes. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 230, 113507 (2023).

Deng, Y. H., Chen, J. H., Yang, Q. & Zhuo, Y. Z. Carbon quantum dots (CQDs) and polyethyleneimine (PEI) layer-by-layer (LBL) self-assembly PEK-C-based membranes with high forward osmosis performance. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 170, 423–433 (2021).

Azami, M. et al. Effect of Doping Heteroatoms on the Optical Behaviors and Radical Scavenging Properties of Carbon Nanodots. J. Phys. Chem. C. 127, 7360–7370 (2023).

Elkun, S., Ghali, M., Sharshar, T. & Mosaad, M. M. Green synthesis of fluorescent N-doped carbon quantum dots from castor seeds and their applications in cell imaging and pH sensing. Sci. Rep. 14, 27927 (2024).

Hu, C. et al. Detection of Fe3+ and Hg2+ ions through photoluminescence quenching of carbon dots derived from urea and bitter tea oil residue. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 272, 120963 (2022).

Li, X., Lau, S. P., Tang, L., Ji, R. & Yang, P. Sulphur doping: a facile approach to tune the electronic structure and optical properties of graphene quantum dots. Nanoscale 6, 5323–5328 (2014).

Giasari, A. S. et al. Role of Sulfur in Enhancing UV-Light Absorption and Photoelectrochemical Performance of ZnO/N,S-doped CQDs Nanocomposite. Chem. Select 9, e202404072 (2024).

Abd Rani, U., Ng, L. Y., Ng, C. Y., Mahmoudi, E. & Hairom, N. H. H. Photocatalytic degradation of crystal violet dye using sulphur-doped carbon quantum dots. Mater. Today Proc. 46, 1934–1939 (2021).

Venkateswara Raju, C., Kalaiyarasan, G., Paramasivam, S., Joseph, J. & Senthil Kumar, S. Phosphorous doped carbon quantum dots as an efficient solid state electrochemiluminescence platform for highly sensitive turn-on detection of Cu2+ ions. Electrochim. Acta 331, 135391 (2020).

Kirbiyik Kurukavak, C., Yılmaz, T., Buyukbekar, A., Tok, M. & Kus, M. Phosphorus doped carbon dots additive improves the performance of perovskite solar cells via defect passivation in MAPbI3 films. Mater. Today Commun. 35, 105668 (2023).

Omer, K. M., Tofiq, D. I. & Hassan, A. Q. Solvothermal synthesis of phosphorus and nitrogen doped carbon quantum dots as a fluorescent probe for iron(III). Microchimica Acta 185, 466 (2018).

Zhou, W. et al. Towards efficient dual-emissive carbon dots through sulfur and nitrogen co-doped. J. Mater. Chem. C. Mater. 5, 8014–8021 (2017).

Xu, J. et al. B, N co-doped carbon dots based fluorescent test paper and hydrogel for visual and efficient dual ion detection. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 145, 110047 (2022).

Newar, R. et al. Development of FRET-based optical sensors using N-doped carbon dots for detection of chromium (VI) and manganese (VII) in water for a sustainable future. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 111721 (2024).

Zamora-Valencia, C. A., Reyes-Valderrama, M. I., Escobar-Alarcón, L., Garibay-Febles, V. & Rodríguez-Lugo, V. Effect of Concentration and pH on the Photoluminescent Properties of CQDs Obtained from Actinidia deliciosa. Cryst. (Basel) 15, 206 (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. Detection of multiple metal ions in water with a fluorescence sensor based on carbon quantum dots assisted by stepwise prediction and machine learning. Environ. Chem. Lett. 20, 3415–3420 (2022).

Roostaee, M. & Ranjbar-Karimi, R. Emerging trends in carbon quantum dots: Synthesis, characterization, and environmental photodegradation applications. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process 188, 109212 (2025).

Shalini, S., Sasikala, T., Tharani, D., Venkatesh, R. & Muthulingam, S. Novel green CQDs/ZnO binary photocatalyst synthesis for efficient visible light irradiation of organic dye degradation for environmental remediation. J. Mol. Liq. 410, 125525 (2024).

Vasiljević, B. R. et al. Designing innovative ZnPc/N-CQDs hybrid material as efficient photocatalyst for environmental remediation. Ceram. Int 51, 29416–29425 (2025).

Tohamy, H.-A. S., El-Sakhawy, M. & Kamel, S. Fullerenes and tree-shaped/fingerprinted carbon quantum dots for chromium adsorption via microwave-assisted synthesis. RSC Adv. 14, 25785–25792 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. Simple fabrication of carbon quantum dots and activated carbon from waste wolfberry stems for detection and adsorption of copper ion. RSC Adv. 13, 21199–21210 (2023).

Sgreccia, E. et al. Heavy Metal Detection and Removal by Composite Carbon Quantum Dots/Ionomer Membranes. Membr. (Basel) 14, 134 (2024).

Rahmanian, O., Dinari, M. & Abdolmaleki, M. K. Carbon quantum dots/layered double hydroxide hybrid for fast and efficient decontamination of Cd(II): The adsorption kinetics and isotherms. Appl Surf. Sci. 428, 272–279 (2018).

Li, H. et al. Design of Red Emissive Carbon Dots: Robust Performance for Analytical Applications in Pesticide Monitoring. Anal. Chem. 92, 3198–3205 (2020).

Gong, N. C. et al. Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer-based Biosensor Composed of Nitrogen-doped Carbon Dots and Gold Nanoparticles for the Highly Sensitive Detection of Organophosphorus Pesticides. Anal. Sci. 32, 951–956 (2016).

Liu, J.-M. et al. Highly selective and sensitive detection of Cu2+ with lysine enhancing bovine serum albumin modified-carbon dots fluorescent probe. Analyst 137, 2637 (2012).

Dong, Y. et al. Polyamine-Functionalized Carbon Quantum Dots as Fluorescent Probes for Selective and Sensitive Detection of Copper Ions. Anal. Chem. 84, 6220–6224 (2012).

Wang, Z., Zhou, C., Wu, S. & Sun, C. Ion-Imprinted Polymer Modified with Carbon Quantum Dots as a Highly Sensitive Copper(II) Ion Probe. Polym. (Basel) 13, 1376 (2021).

Vyas, T. & Joshi, A. Chemical sensor thin film-based carbon quantum dots (CQDs) for the detection of heavy metal count in various water matrices. Analyst 149, 1297–1309 (2024).

Alshammari, G. M. et al. Development of luminescence carbon quantum dots for metal ions detection and photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes from aqueous media. Environ. Res 226, 115661 (2023).

Šafranko, S. et al. An Overview of the Recent Developments in Carbon Quantum Dots—Promising Nanomaterials for Metal Ion Detection and (Bio)Molecule Sensing. Chemosensors 9, 138 (2021).

Qaddare, S. H. & Salimi, A. Amplified fluorescent sensing of DNA using luminescent carbon dots and AuNPs/GO as a sensing platform: A novel coupling of FRET and DNA hybridization for homogeneous HIV-1 gene detection at femtomolar level. Biosens. Bioelectron. 89, 773–780 (2017).

Wang, K. et al. Highly Sensitive and Selective Detection of Amoxicillin Using Carbon Quantum Dots Derived from Beet. J. Fluoresc. 28, 759–765 (2018).

Chandra, S., Mahto, T. K., Chowdhuri, A. R., Das, B. & Sahu, S.K. One step synthesis of functionalized carbon dots for the ultrasensitive detection of Escherichia coli and iron (III). Sens Actuators B Chem. 245, 835–844 (2017).

Zhang, Q. Q. et al. Inner filter with carbon quantum dots: A selective sensing platform for detection of hematin in human red cells. Biosens. Bioelectron. 100, 148–154 (2018).

Das, P. et al. Heteroatom doped photoluminescent carbon dots for sensitive detection of acetone in human fluids. Sens Actuators B Chem. 266, 583–593 (2018).

Wang, J., Lu, T., Hu, Y., Wang, X. & Wu, Y. A label-free and carbon dots based fluorescent aptasensor for the detection of kanamycin in milk. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 226, 117651 (2020).

Daby, T. P. M., Modi, U., Yadav, A. K., Bhatia, D. & Solanki, R. Bioimaging and therapeutic applications of multifunctional carbon quantum dots: Recent progress and challenges. Nanotechnology 8, 100158 (2025).

Shen, P. & Xia, Y. Synthesis-Modification Integration: One-Step Fabrication of Boronic Acid Functionalized Carbon Dots for Fluorescent Blood Sugar Sensing. Anal. Chem. 86, 5323–5329 (2014).

Lim, S. Y., Shen, W. & Gao, Z. Carbon quantum dots and their applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 362–381 (2015).

Wang, B. et al. Carbon Dots in Bioimaging, Biosensing and Therapeutics: A Comprehensive Review. Small Sci. 2, 220002 (2022).

Anpalagan, K. et al. A Green Synthesis Route to Derive Carbon Quantum Dots for Bioimaging Cancer Cells. Nanomaterials 13, 2103 (2023).

Arkan, E. et al. Green Synthesis of Carbon Dots Derived from Walnut Oil and an Investigation of Their Cytotoxic and Apoptogenic Activities toward Cancer Cells. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 8, 149–155 (2018).

Tadesse, A., Hagos, M., RamaDevi, D., Basavaiah, K. & Belachew, N. Fluorescent-Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots Derived from Citrus Lemon Juice: Green Synthesis, Mercury(II) Ion Sensing, and Live Cell Imaging. ACS Omega 5, 3889–3898 (2020).

Yukawa, H., Sato, K. & Baba, Y. Theranostics applications of quantum dots in regenerative medicine, cancer medicine, and infectious diseases. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 200, 114863 (2023).

Bhamare, U. U., Patil, T. S., Chaudhari, D. P. & Palkar, M. B. Emerging Versatile Role of Carbon Quantum Dots in Theranostics Applications for Breast Cancer Management. Chem. Nano Mat. 11, e202500030 (2025).

Karimi, M. et al. Development of a novel nanoformulation based on aloe vera-derived carbon quantum dot and chromium-doped alumina nanoparticle (Al2O3:Cr@Cdot NPs): evaluating the anticancer and antimicrobial activities of nanoparticles in photodynamic therapy. Cancer Nanotechnol. 15, 26 (2024).

Kumar, A. et al. Next-Generation Cancer Theragnostic: Applications of Carbon Quantum Dots. Chem. Nano Mat. 11, e202500061 (2025).

Ashrafizadeh, M. et al. Carbon dots as versatile nanoarchitectures for the treatment of neurological disorders and their theranostic applications: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 278, 102123 (2020).

Kumar, J., Delgado, S. A., Sarma, H. & Narayan, M. Caffeic acid recarbonization: A green chemistry, sustainable carbon nano material platform to intervene in neurodegeneration induced by emerging contaminants. Environ. Res 237, 116932 (2023).

Nair, A., Haponiuk, J. T., Thomas, S. & Gopi, S. Natural carbon-based quantum dots and their applications in drug delivery: A review. Biomedicine Pharmacother. 132, 110834 (2020).

Li, S. et al. Targeted tumour theranostics in mice via carbon quantum dots structurally mimicking large amino acids. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 704–716 (2020).

Koyale, P. A. & Delekar, S. D. A review on practical aspects of CeO2 and its composites for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Int J. Hydrog. Energy 51, 515–530 (2024).

Mehta, A. et al. Band gap tuning and surface modification of carbon dots for sustainable environmental remediation and photocatalytic hydrogen production – A review. J. Environ. Manag. 250, 109486 (2019).

Miao, R. et al. Mesoporous TiO2 modified with carbon quantum dots as a high-performance visible light photocatalyst. Appl Catal. B 189, 26–38 (2016).

Martindale, B. C. M., Hutton, G. A. M., Caputo, C. A. & Reisner, E. Solar Hydrogen Production Using Carbon Quantum Dots and a Molecular Nickel Catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 6018–6025 (2015).

Sivagurunathan, P. et al. Synergistic role of carbon quantum dots on biohydrogen production. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 114188 (2024).

Sharma, M., Kafle, S. R., Singh, A., Chakraborty, A. & Kim, B. S. Carbon quantum dots for efficient hydrogen production: A critical review. Chem. Cat Chem. 16, e202400056 (2024).

Gui, X., Lu, Y., Wang, Q., Cai, M. & Sun, S. Application of Quantum Dots for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Appl. Sci. 14, 5333 (2024).

Chen, Y., Huang, G., Gao, Y., Chen, Q. & Bi, J. Up-conversion fluorescent carbon quantum dots decorated covalent triazine frameworks as efficient metal-free photocatalyst for hydrogen evolution. Int J. Hydrog. Energy 47, 8739–8748 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Metal-Free Carbon Quantum Dots Implant Graphitic Carbon Nitride: Enhanced Photocatalytic Dye Wastewater Purification with Simultaneous Hydrogen Production. Int J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1052 (2020).

Elsayed, M. H. et al. Visible-light-driven hydrogen evolution using nitrogen-doped carbon quantum dot-implanted polymer dots as metal-free photocatalysts. Appl Catal. B 283, 119659 (2021).

Wang, Q. et al. Morphology-engineered carbon quantum dots embedded on octahedral CdIn2S4 for enhanced photocatalytic activity towards pollutant degradation and hydrogen evolution. Environ. Res 209, 112800 (2022).

Zhou, X. et al. MoC Quantum Dots@N-Doped-Carbon for Low-Cost and Efficient Hydrogen Evolution Reaction: From Electrocatalysis to Photocatalysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2201518 (2022).

Ye, C. et al. Highly Efficient and Stable Potassium-Doped g-C3 N4 /Zn0.5 Cd0.5 S Quantum Dot Heterojunction Photocatalyst for Hydrogen Evolution. Battery Energy 4, 20240033 (2025).

Chen, Q. et al. Carbon dots mediated charge sinking effect for boosting hydrogen evolution in Cu-In-Zn-S QDs/MoS2 photocatalysts. Appl Catal. B 301, 120755 (2022).

Ríos, E. H. et al. Effect of the oil content on green hydrogen production from produced water using carbon quantum dots as a disruptive nanolectrolyte. Int J. Hydrog. Energy 76, 353–362 (2024).

Arora, G., Sabran, N. S., Ng, C. Y., Low, F. W. & Jun, H. K. Applications of carbon quantum dots in electrochemical energy storage devices. Heliyon 10, e35543 (2024).

Fan, J. et al. Recent Progress of Quantum Dots Light-Emitting Diodes: Materials, Device Structures, and Display Applications. Adv. Mater. 36, 2312948 (2024).

Giordano, M. G., Seganti, G., Bartoli, M. & Tagliaferro, A. An Overview on Carbon Quantum Dots Optical and Chemical Features. Molecules 28, 2772 (2023).

Lesiak, A. et al. Optical Sensors Based on II-VI Quantum Dots. Nanomaterials 9, 192 (2019).

Phang, S. J. & Tan, L. L. Recent advances in carbon quantum dot (CQD)-based two dimensional materials for photocatalytic applications. Catal. Sci. Technol. 9, 5882–5905 (2019).

McDonald, S. A. et al. Solution-processed PbS quantum dot infrared photodetectors and photovoltaics. Nat. Mater. 4, 138–142 (2005).

Shabbir, H. & Wojnicki, M. Recent Progress of Non-Cadmium and Organic Quantum Dots for Optoelectronic Applications with a Focus on Photodetector Devices. Electron. (Basel) 12, 1327 (2023).

Chen, S., Zu, B. & Wu, L. Optical Applications of CuInSe 2 Colloidal Quantum Dots. ACS Omega 9, 43288–43301 (2024).

Shi, Y. et al. Onion-like multicolor thermally activated delayed fluorescent carbon quantum dots for efficient electroluminescent light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 15, 3043 (2024).

Hoang Huy, V. P. & Bark, C. W. A self-powered photodetector through facile processing using polyethyleneimine/carbon quantum dots for highly sensitive UVC detection. RSC Adv. 14, 12360–12371 (2024).

Mimona, M. A. et al. Quantum dot nanomaterials: Empowering advances in optoelectronic devices. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 21, 100704 (2025).

Bozyigit, D., Yarema, O. & Wood, V. Origins of Low Quantum Efficiencies in Quantum Dot LEDs. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 3024–3029 (2013).

Lin, Q. et al. A Full-Quantum-Dot Optoelectronic Memristor for In-Sensor Reservoir Computing System with Integrated Functions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2423548 (2025).

Kim, M., Oh, S., Song, S., Kim, J. & Kim, Y.-H. Solution-Processed Memristor Devices Using a Colloidal Quantum Dot-Polymer Composite. Appl. Sci. 11, 5020 (2021).

Xu, K., Zhou, W. & Ning, Z. Integrated Structure and Device Engineering for High Performance and Scalable Quantum Dot Infrared Photodetectors. Small 16, 2003397 (2020).

Ikram, Z., Azmat, E. & Perviaz, M. Degradation Efficiency of Organic Dyes on CQDs As Photocatalysts: A Review. ACS Omega 9, 10017–10029 (2024).

G, P. et al. Role of carbon quantum dots in a strategic approach to prepare pristine Zn2SnO4 and enhance photocatalytic activity under direct sunlight. Diam. Relat. Mater. 131, 109554 (2023).

Meena, S. et al. Molecular surface-dependent light harvesting and photo charge separation in plant-derived carbon quantum dots for visible-light-driven OH radical generation for remediation of aromatic hydrocarbon pollutants and real wastewater. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 660, 756–770 (2024).

Hassan Ahmed, H. E. & Soylak, M. Exploring the potential of carbon quantum dots (CQDs) as an advanced nanomaterial for effective sensing and extraction of toxic pollutants. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 180, 117939 (2024).

Huang, X., Zhang, H., Zhao, J., Jiang, D. & Zhan, Q. Carbon quantum dot (CQD)-modified Bi3O4Br nanosheets possessing excellent photocatalytic activity under simulated sunlight. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process 122, 105489 (2021).

Ali, F., De Juan-Corpuz, L. M. & Corpuz, R. D. Unlocking the potential of carbon quantum dots: Versatile photocatalysts for methylene blue degradation—A comprehensive review of synthesis, catalytic mechanisms, and environmental applications. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 71, 1154–1171 (2024).

Gencer, Ö The production of carbon quantum dots (CQDs) from cultivated blue crab shells and their application in the optical detection of heavy metals in aquaculture. Aquac. Int. 33, 107 (2025).

Bijoy, G. & Sangeetha, D. Biomass derived carbon quantum dots as potential tools for sustainable environmental remediation and eco-friendly food packaging. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 113727 (2024).