Abstract

Indonesia contributes to greenhouse gas emissions but is also vulnerable to climate change. However, the country does not have a single, overarching law explicitly addressing climate change. Climate litigation is now used in Indonesia to hold governments and corporations accountable. Here, I review the courts’ decisions for criminal and civil climate change-related cases between 2010 and 2020 and highlight trends and examples of case studies, driving factors, and impacts of climate litigation cases in Indonesia. I show that 112 climate change-related cases were brought to Indonesian courts, most of which were criminal cases concerning forestry or forest fires. In addition, there were a number of civil court cases. The cases use phrases concerning climate change in their main claim, argument, evidence, expert witness arguments, and judgments. They are regarded as incidental climate change litigation cases. However, these cases are essential in developing climate change litigation in Indonesia because they open up a discussion of climate change issues in the Indonesian courts and public media.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The definition of climate change related litigation varies. For instance, Hilson adopts a broad approach, stating that ‘virtually all litigation could be conceived of as [climate change related litigation]’ given that ‘climate change is the consequence of billions of everyday human actions, personal, commercial, and industrial’1. However, we have seen cases2,3,4,5,6 that have more direct links to climate change: litigation related to mitigation (e.g. directly addressing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions) or litigation related to adaptation (e.g. predicted impacts of climate change on ecosystems, communities, and infrastructure)7. Litigants in those cases may have sought to promote climate change regulation or to oppose existing or proposed regulatory measures7.

Climate change can also be raised as a peripheral issue in the litigation process. Here, concerns over climate change motivate the lawsuit, at least in part, but are not explicitly raised in the claims or decision. Peel and Osofsky present their concept of climate change related litigation as a series of concentric circles7. Furthermore, Kim Bouwer argues that climate change litigation occurs at varied scales, yet smaller cases at lower levels of governance are as important as more high-profile cases, and engage all elements of a good climate response8. She underlines that if we restrict ourselves to only ‘core cases’ of climate change related litigation and ignore the peripheral / smaller cases, we would be losing much potential lessons to be learned from those cases. To take this even further, this study opines that ‘climate change related litigation’, or litigation which incidentally mention climate change issues in their dossiers, would also have an impact on the overall development of climate change litigation, as evident in cases where judicial deliberation and decisions specifically indicate that climate change is a determining factor.

This study aims to show that Indonesia is no stranger to incidental cases of climate change litigation9,10, through: (1) detecting criminal and civil climate change related cases that have been brought before the courts between the years 2010 and 2020; (2) dissecting examples of case studies; and (3) highlighting the trends, driving factors, and impacts of climate change related litigation in Indonesia. Notably, some reports have not considered Indonesia a country active in climate change litigation during the research period of 2010 to 202011,12. For instance, in the Climate Case Chart12, as per 2024, there are only 15 cases listed as climate change litigation cases in Indonesia. This is because of the categorization adopted in their ‘global database’, which are: (a) case categories, including the type of defendant and main cause of action; (b) jurisdiction; (c) climate relevant principal law to which the litigation relates; and (d) status of the case. Most of the ‘incidental’ climate change cases are not included, because climate change was not the relevant principal law to which the litigation related to. Similarly, in the 2024 Global Climate Litigation Report Status Review by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), Indonesia is listed as only having 12 climate litigation cases until year 2022, as the report utilized the same narrow definition of climate change litigation used by the Sabin Center11. In contrast, there are previous studies which have pointed out the typology of climate change related litigation cases in Indonesia13 and a study on the challenges of climate change related litigation in Indonesia14. These studies reveal that Indonesia has had criminal, civil, administrative, and even judicial review cases that include climate change in various stages of their dossiers. In these incidental climate change cases, the issue of climate change was mentioned either in an indictment, a party’s argument, part of submitted evidence, part of an expert witnesses’ argument, judges’ considerations, or in the judgments. These cases are listed in the Supplementary Data 1, submitted together with this article.

Indonesian climate related regulations

Indonesia ratified the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Kyoto Protocol. Prior to the 2015 Paris Agreement, Indonesia’s regulations on climate change refer to the UNFCCC. Key examples include: the (1) Presidential Regulation No. 61 of 2011 on National Action Plan for the Reduction of Emissions of Greenhouse Gases (PR 61/2011); and the (2) Presidential Regulation No. 71 of 2011 on the Implementation of a National Inventory of Greenhouse Gases (PR 71/2011). Indonesia ratified the Paris Agreement in 2016, and its’ Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) is to reduce its GHG by twenty-nine percent independently, and forty-one percent with international support of the business-as-usual scenario by 203015. Indonesia’s enhanced NDC, updated in September 2022, increased independent GHG reduction to thirty-one point eighty nine percent, and forty three point two percent with international support15.

Indonesia does not have a single, overarching law specifically on climate change. At the time period of this study (2010 to 2020), Indonesia still relied on its environmental laws as the main framework to help mitigate climate change. Cases referred to in this study therefore uses the legal framework available at that time. The environmental laws include the Indonesian Penal Code on Law No.1/1946, Law No. 32/2009 on Environmental Protection and Management, and Law No. 41/1999 on Forestry. Other regulations in relation to climate change, among others, include: Indonesia’s Civil and Criminal Codes, Law No. 4/2009 (Mineral and Coal Mining Act), Law No.18/2013 (Avoidance of Deforestation and Forest Degradation Act), Law No.39/2014 (Farming Law), and Law No.39/1999 (Human Rights Law).

Indonesian courts

The Indonesian court system is divided in two: (1) a Supreme Court (Mahkamah Agung) to oversee the work of the judiciary and Lower Courts; and (2) a separate Constitutional Court (Mahkamah Konstitusi)16. Most civil and criminal trials are run through the hierarchy of District Courts (pengadilan negeri), starting from the regency level (kabupaten), moving to Appeal Courts (pengadilan tinggi), and then obtaining a final cassation from the Supreme Court17.

Results

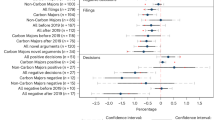

In total, this study analyses 112 court cases from 2010 to 2020 from the District, High and Supreme Courts. There are too many variables to discuss in terms of administrative and review cases in climate change related litigation, and independent research is needed to discuss these issues. For these reasons, only criminal and civil cases are elaborated on in the next sections.

Criminal cases

Out of all the climate change related litigation cases, most (71%) were criminal cases. Of these criminal cases, most are forestry or forest fires related, including matters relating to haze, air pollution, or illegal logging. Climate change was included in the cases, mostly by the expert witness in their testimonies, but also in the judges’ considerations (see Table 1). Fourteen cases, in which climate change was used as a theme in the cases’ indictment, were also found. These cases are listed in case no. 1 to 80 in the Supplementary Data 1, attached.

The first key point from this study is that, in the cases analysed, climate change was not used as the first argument, but rather as an impact of the first argument. For example, in forestry cases involving forest fires or illegal logging, plaintiffs argued that if the forested areas were damaged, the microclimate system will be pressured, thereby exacerbating global climate change18,19,20,21,22. In Case No. 27/PID.B/2013/PN.WTP (Prosecutor v. Nurung bin Nase, verdict: guilty), one of the bases for the allegations is that “the Defendant’s actions can cause immeasurable non-material losses, namely micro-climate changes at the location of the incident”18. Another case, Case No.94/PID.SUS/2014/PN.TBH (Prosecutor v. H. Marbawi, verdict: guilty), the Court noted the report from the Forest and Land Fire Laboratory, Forest Protection Department, Faculty of Forestry, Bogor Agricultural University, that “the land burning caused damage to the 10 cm thick surface layer of the land, which had a detrimental impact on living organisms and the water system. Additionally, the land burning also resulted in greenhouse gases emissions”19. It is noted that, in these cases, climate change was often mentioned as a ‘future’ impact without really going into detail as to the impact themselves. These phrases are clearly inserted to highlight the climate and environmental impacts suffered by the prosecutor/claimant. On the whole, climate change had been considered by judges in their verdicts (twenty-eight cases), were mentioned by experts in their expert witness testimony (thirty-two cases), and were cited in the indictment submitted by the prosecution (fourteen cases). These cases are listed in the Table of Cases-Climate Change Related Litigation 2010–2020 Indonesia (Criminal Cases), as Case no. 2 and no. 4 in the Supplementary Data 1, attached.

Second, based on the Courts’ files for these criminal cases, the understanding of climate change proves to be superficial. This is evidenced by some judgments and indictments23,24,25 which mention climate change as an impact of illegal logging or forest fires in the same way that floods, droughts, and landslides are mentioned: merely as part of a list of consequences of changing the forest system. These findings demonstrate an insufficient understanding of precisely how the acts exacerbate climate change, which worsens extreme weather events and ecological breakdown26. Seventy-one cases were settled at the District Court level, while four cases proceeded to the appellate courts and another four cases went to proceeded to the Court of Cassation. Given that a majority of cases are not appealed, this indicates that either most defendants are satisfied with the outcome of the case, or that there are other administrative burdens which disincentivised the defendants from filing an appeal (eq. high court fees, lawyer fees, etc)27. Seventy-six out of eighty of criminal climate related cases received guilty verdicts, and of the seventy-six, twenty-eight clearly mentioned key phrases of climate change or climate change impacts in the judges’ considerations. The fact that climate change was included in these criminal cases shows that Indonesian legal enforcers were familiar with climate change as a disaster caused by human action. While this can be considered a breakthrough in Indonesian criminal cases, there remains a need to empower legal practitioners and judges with education and training on climate change.

Third, since most of these cases are forestry and environment related cases, it is more likely that the judges deciding these cases understood the severity or possibility of detrimental environmental/climate impacts in these cases. There are judges’ certification on environmental law in Indonesia’s judicial system, and around 425 judges (or 10% of the total judges in Indonesia) have received training and said certification28. The ability of the judges to listen and set aside biases, leadership of the judges, and detachment of the judge are also among other things needed29. However, judicial education and training on environmental law issues (including climate issues) still needs to be deepened as most verdicts are based upon superficial related climate arguments—as elaborated in the second point above.

Fourth, most cases (seventy-two cases) involved forest fires or other forestry related matters. This reflects how forestry cases are very close to climate change issues and that there is available scientific evidence linking them both. By linking forestry issues with the scientific evidence of climate change in these cases, the chances of prosecution for these cases have increased. This is further elaborated upon in the Discussion section below.

Furthermore, these cases also utilise human rights arguments in relation to climate change. Several forest fires and mining cases30,31 highlighted how the local communities lost their access to clean air, clean water, and an overall good quality of life. For example, the Pangkalan Bun District Court in Prosecutor v Hairil (Case no.168/PID.B/LH/2018/PN Pbu, verdict: guilty) stated that the defendant purposefully set fire in the farming and forest area, resulting in excessive smoke which exceeded the limit permitted in his farming area. The judges considered that “physical and environmental biota play a very important role in supporting human livelihood and welfare. Therefore, land degradation resulting from burning practices will have an impact on the existing climate”. Further, in Prosecutor v Danar Bata (Case no. 6/PID.SUS.TPK/2020/PN Gto in Gorontalo District Court, verdict: guilty), where the defendant was found guilty of embezzlement during the development of a water dam project, one of the witnesses stated that: “the purpose of building these reservoirs and dams is to provide facilities and infrastructure for water resource management in order to address the impacts of climate change, thus making it possible to utilize them as a source of irrigation water”. In that case, the defendant’s embezzlement hampered the dam development to the extent of hampering the local community’s right to receiving adequate water supply. All of these are basic human rights that relate closely to climate change. However, these cases did not directly mention human rights, which would have given more substantiation toward linking human rights and climate change impacts27. These cases are listed in the Table of Cases-Climate Change Related Litigation 2010–2020 Indonesia (Criminal Cases), as Case no. 10 and no.11 in the Supplementary Data 1, attached.

Civil cases

This study found that fourteen climate change related litigation cases were heard in the Indonesian Civil Courts between 2010 and 2020 (see Table 2). Environmental cases in Indonesia come under the purview of Environmental Protection and Management Law 2009. This law states that a lawsuit can only be brought before any court if all other alternative dispute resolution methods have been declared unsuccessful by one or all disputing parties. Thus, it is possible that the number of cases identified in this study form only a small part of the total number of climate change related disputes, while the rest have been settled through alternative dispute resolution processes prior to court proceedings.

First, the number of climate change related litigation cases in civil law are much smaller than that in criminal law. However, arguments involving climate change run deeper and are more meaningful. In civil cases, climate change has often been brought up in arguments either as scientific evidence or in requests to the government to enact or revise regulations to mitigate or adapt to to climate change. For example, in the case of Ari Rompas and friends v. the Government of Indonesia (Case no. 980 PK/PDT/2022, verdict: in favour of the plaintiff) climate change was part of their claim that the Indonesian government failed to fulfil its responsibility to regulate and implement policies on climate change and ozone layer protection32. All levels of the Courts accepted the claims and requested the government to revise and remand the regulations, although recent developments in 2022 showed that Government of Indonesia (GoI) submitted a successful case review (peninjauan kembali), which annulled previous decisions33. This case is listed the Table of Cases-Climate Change Related Litigation 2010–2020 Indonesia (Civil Cases), as Case no. 5 in the Supplementary Data 1, attached.

Second, eighty percent of the cases were settled in first instance courts, indicating that most litigants had already obtained the justice they desired in the District Court rulings. However, out of these cases, five of twelve of them were declined due to various reasons, such as error in persona (wrongfully inputting the details of the defendant), legal standing issues (plaintiff did not have standing for the case), plurium litis consortium (claim lacked parties; the claim should have included governor and/or head of district as the responsible party), and obscuur libel (unclear claim)34,35,36. These reasons do not have anything to do with climate change. Rather, they demonstrate that external factors may complicate the process and outcome of climate change related litigation.

Third, the rigidity of legal standing rules has proven to be problematic. There are five types of standing for civil cases in Indonesia: citizen lawsuit, class action, non-governmental organisation (NGO) claim, state (or ministries) claims against company and/or individual, and regular claim. In practice, filing a lawsuit is complicated for environmental organisations. Article 92 of the Environmental Protection and Management Law 2009 states that in order for an environmental organisation to bring a lawsuit for environmental conservation purposes, it must: (a) be incorporated37; (b) have asserted in its statute that the organisation was founded for the sake of environment conservation37; and (c) have had undertaken concrete activities in accordance with its statute for at least two years37. Furthermore, the right to bring this lawsuit is limited to demands to perform certain actions without any claim for compensation, except for the costs or real expenses37. As such, we can see that not only is establishing legal standing for environmental cases is limited, its potential scope and impact are likewise limited.

It is interesting to note that the Indonesian Ministry of Environment and Forestry was a party in all of these cases, either as a plaintiff or as a defendant. Evidently, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry is committed to being involved in climate change related cases and is using climate change related litigation to resolve climate change disputes. Other stakeholders, such as private businesses and NGOs, are also involved in these climate change related litigation cases38.

Fourth, in civil climate change related litigation cases, scientific evidence of climate impacts have often been used as the basis for plaintiffs’ claims and have also been attested to in expert witness testimonies. Moreover, the arguments related to climate change and its impacts were then linked to the loss of human rights. We see this in the citizen lawsuit claims, such as Komari v. Mayor of Samarinda39 (verdict: in favour of plaintiff) and Ari Rompas v Government of Indonesia32 (verdict: in favour of plaintiff, but then annulled in the Supreme Court in 2022), as well as in claims made by organisations, such as WALHI v Government of Indonesia35 (lawsuit inadmissible) and even in claims made by the government, such as Ministry of Environment and Forestry v PT. Palmina Utama36 (verdict: in favour of plaintiff) and Ministry of Environment and Forestry v PT. Arjuna Utama Sawit40 (verdict: partially granted). These cases are listed in the Table of Cases-Climate Change Related Litigation 2010–2020 Indonesia (Civil Cases), as Case no. 2, 5, 6, 7 and 8, in the Supplementary Data 1, attached.

Discussion

Driving factors of climate change related cases in Indonesian court during 2010–2020

Climate change related litigation cases within the period of 2010 to 2020 are shown in the graphs above (see Figs. 1 and 2). This study discovered that this progress is attributable to several driving factors. Firstly, the development of science in climate change issues, such that litigants can use them as grounds for their claims. Consistent with Burger’s argument41, we have seen how climate change related litigation cases in Indonesia have been utilising scientific developments by: (i) introducing expert scientific testimonies and reports as evidence in criminal and civil cases to explain the causal links between GHG emissions and climate change; and (ii) challenging government failure to regulate GHG emissions in civil cases.

Expert witness testimony has played, and continues to play, an important role in linking climate change science to the cases. In criminal cases, thirty nine out of eighty cases have included expert witness testimonies elaborating on the climate change implications of forest-related incidents. For example, in the Case No. 254/PID.SUS/2017/PN PLW (on illegal logging, verdict: guilty), the expert witness testimony stated that “ecologically, the Defendant’s actions can lead to the conversion of forest functions into plantation areas. Additionally, the damage to the Kerumutan Forest can result in the disruption of the ecosystem, climate, and the extinction of several wildlife species”. In the Case 140/Pid.Sus/2013/PN. PLW (on encroachment, verdict: guilty), the expert witness testimony highlighted, “the actions of the defendant, utilizing the Tesso Nilo National Park (TNTN) for palm oil and rubber plantations, are not in accordance with its designated function. This has led to the loss of TNTN’s ability to maintain its role as a flood control area, carbon dioxide absorber, oxygen supplier, and regulator of global climate, among other functions”. Here, we see the concrete link between the scientific evidence of climate change and climate catastrophe. In civil cases, two out of fourteen cases studied had expert witness testimonies featuring climate change considerations. This number is small, but it indicates that judges take into consideration climate science when adjudicating. Moreover, the remaining twelve cases featured climate change in their claims. These cases are listed in the Table of Cases-Climate Change Related Litigation 2010–2020 Indonesia (Criminal Cases), as Case no. 8 and no. 16 in the Supplementary Data 1, attached.

Out of fourteen civil cases studied, seven cases challenge the Government on the basis of their failure to regulate GHG emissions. Both local and national Governments were involved; requests were made to the local leaders (mayor or governor), or the Minister of Environment and Forestry to revise or revoke current regulations and any implementation efforts thereunder. In three cases, such requests were even aimed at the President of Indonesia. This shows how plaintiffs in these cases understand the importance of GHG emission reduction on mitigating climate change, and that enacting and implementing the relevant regulations forms part of the Government’s responsibility.

Secondly, the development of nexus between human rights and climate change, as litigants can use the link between their human rights issues to climate change impacts. In the international sphere, the nexus between human rights and climate change has been increasingly acknowledged. The preamble of the Paris Agreement specifies that parties ‘should when taking actions to address climate change, respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights’42, and the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) had adopted 11 resolutions on human rights and climate change43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53. This development helps national and sub-national actors to easily link the effects of climate change to the fulfillment of human rights in climate change cases.

Specifically, climate change compromises the human right to life, right to adequate food, right to the enjoyment of highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, right to adequate housing, right to self-determination, right to safe drinking water and sanitation, right to work and the right to development43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53. In the cases examined in this article, we have seen arguments highlighting how environmental damage would lead to a deterioration of the quality of life of the people living in the affected areas. In deforestation cases, the argument most used in relation to the impact of climate change on human rights was that deforestation caused the forest to lose its water retaining capacity, consequently endangering access to clean water and/or a good quality of living. Although these links might seem obvious and simple, there is potential to explore their nuances and implications. Therefore, it is expected that as climate change related litigation continues to grow, so too will the nexus between human rights and climate change.

Thirdly, judicial training and certification on environmental law, so they know how to proceed with environmental cases. Indonesia had initially planned to establish an environmental court system54, but decided to install ‘green judges’ or ‘green benches’ in the general courts instead37. This demonstrates Indonesia’s aspiration to have regular court judges proficient in environmental issues11. Judges who have been trained in environmental issues are given an ‘environmental judges certification’ to certify their expertise in handling environmental issues. Furthermore, all environmental cases are tried with at least one certified judge55. However, as discussed, this training and certification needs to be amped up and pushed for as current statistics reveal that only 10% of judges in Indonesia have the environmental law certification11.

Fourthly, increased transparency and public pressures on climate change court cases. For example, the Indonesian Supreme Court started a website publishing all court documents on their website in 2011. As such, environmental cases can be accessed, read, and analysed by the public. Moreover, a new service had also been added to the Court’s website: an ‘e-Court’ wherein plaintiffs can register, get an e-summon, engage in e-litigation, receive an e-copy of the verdict, and e-sign documents.

Furthermore, Law No. 14 of 2008 on Public Information Disclosure obliges the Government to provide accurate information in timely manner to the public. Fulfilling this obligation thus requires the Government to provide facilities such as buildings or rooms for complaints, a complaint desk, and an online complaint network.

On top of that, public pressures from the civil society and environmental NGOs in Indonesia have been increasing. The number of environmental NGOs in Indonesia has grown immensely: there were 8720 in 1990 and this figure grew to 13,400 in 200056. Although there have been criticisms on the effectivity and transparency of these environmental NGOs, these NGOs are generally recognised and relied upon as watchdogs who monitor the government and court activities in relation to the environment and climate change57.

Lastly, government support and political will for climate change related litigation. The support can be in the form of moral and political support, where the government conferred the courts with legal authority to work independently, providing them with a sufficient budget, infrastructure, human resources, and security. In criminal and civil climate change cases, we saw that the government, especially the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF), was extensively involved. In the criminal cases, we saw that the prosecutors often referred to MoEF reports and/or permits for evidence, or as expert witness providing testimony for the cases; in civil cases, the MoEF was directly involved as litigants, despite, as we had previously examined, how the GoI is adamant in pushing for the annulment of unfavourable verdicts through cassation and case review (peninjauan kembali). This shows conflicting governmental priorities in Indonesia. Indeed, climate change related litigation appears to be in tension with the governmental pursuit of economic development based on a carbon-intensive economic growth model, because it may upend the current political and economic system, the system that gave rise to the climate crisis in the first place14.

In terms of political will, environment and disaster resilience was listed as priority under Agenda 9 of the National Development Medium Term Plan (Rencana Pembangunan Nasional Jangka Menengah, RPJM) 2009-201458. Subsequently, the RPJM 2015–2019 listed not only environmental and disaster resilience, but also included climate change issues into the cross-sectoral development plan59. The latest RPJM 2020-2024 builds on the previous RPJMs and lists climate change as a priority and includes low carbon development within the agenda60. In addition, it should be noted that each RPJM explicitly highlights the development of equity and justice within the courts of Indonesia. Each of the RPJMs would list accomplishments of the last RPJM and include more ambitious goals, just like what we have seen with climate change issues. For example, abatement of forest fires was a priority within the disaster and climate resilient agenda of RPJM 2015–2019. As a result, Indonesia’s annual forest fires have been reduced by seventy-five percent from 1990 levels in 202061.

The roles of climate change related litigation cases in Indonesian courts

Even though these cases are incidental cases on climate change, this study argues that they hold important roles in the evolution of climate change issues in Indonesian courts. Their roles include firstly, opening a discussion on climate change in the Indonesian courts. Litigants, law enforcers, and the Courts have familiarized themselves with these issues because of these cases. These cases show that through the years, the inclusion of climate change as a claim increases the confidence of litigants.

Secondly, some of these cases (especially the civil cases) became popular and were taken up by national and international media. Media coverage brought attention to the cases and issues at hand, making the public more aware of the legal proceedings. The increased visibility led to greater accountability for the justice system, as the actions and decisions of judges, lawyers, and other stakeholders were scrutinized by a wider audience. Media coverage also contributed to a more transparent legal process, shaped public opinion about the cases and the parties involved, and introduced the public to the discourse of climate change in the courts. In broader terms, media coverage also influenced public trust in the justice system. Fairness and effectiveness of the legal process for these cases were shown in the open such that the public could directly see and build perceptions of the performance of the courts.

Thirdly, these cases can increase the social and political charges towards the Courts and the Government. With the exposure of climate change as an issue in court cases, aside from triggering social and political discussions, it can also lead to action and changes in laws, policies, or regulation related to the issues raised by these cases. As seen in Komari v. Mayor of Samarinda39 and Ari Rompas v Government Indonesia32, these cases had the potential to push the government to change the current regulations to the betterment of the climate and the environment. Even though both cases were rejected at the Supreme Court level, the discourse of climate change had already taken place in the country, and actions and changes had taken place in Indonesia. Many campaigners, public discussions, as well as books and research reports pushed the government of Samarinda and Palangkaraya to upgrade their policies and regulations for the betterment of the climate and the environment. These cases built a bridge for more ‘core’ climate change litigation cases in the Indonesian judiciary.

Overall, these results demonstrate the complexity of climate change related cases in Indonesia. Nevertheless, there is improvement from the fact that law enforcers and litigants are using climate change as a basis for their claims. This shows that the issue of climate change has been accepted as increasingly important, to the extent that it is accepted as an argument in court, and possibly beneficial one at that. Indonesians are fully aware of their own rights and obligations and understand that it is the responsibility of the State to protect these rights, including the human right of being safe from the threats posed by climate change. This might be the dawn of the new beginning for the future of ‘core’ climate change litigation in Indonesia. Further research needs to be done in other jurisdictions, to see whether this situation of incidental climate change cases exists and are playing vital roles to give opportunities for more ‘core’ climate change litigation cases to thrive.

Conclusion

In conclusion, climate change is a crucial issue in Indonesia, and its importance is attested to by its growing presence in Indonesian litigation. Climate change related issues are being contested in Indonesian courts in the study period of 2010 to 2020. They are not ‘core’ climate change litigation cases, but rather, are ‘incidental’ climate change litigation cases which can easily being overlooked as ‘climate change issues’ are not the core argument discussed in those cases. However, this study concludes that in the 112 ‘incidental’ climate change related litigation cases in Indonesia from 2010 to 2020, most of the cases were pushing upon favourable outcomes toward climate change mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage compensation. In the 80 criminal cases, 42 of them are looking for mitigation and compensation for loss and damages, 2 are corruption cases which seek damages toward the environment, 18 are natural resources related which requested for reclamation of the environment and mitigation of climate change. In the 14 civil cases, all of them requested for the betterment of policies and regulations involving the environment, including climate change. This means that these civil cases are pushing for adaptation, and mitigation action from the Government.

Even though these cases are ‘incidental’ climate change litigation cases, this study contends that they have opened a discussion on climate change issues in the Indonesian courts during the study period, managed to expose climate change issues in the media, and in turn, increased social and political charges toward the Courts, the Government, and the justice system in the country, building a bridge for a brighter future of climate litigation in Indonesia.

Methodology

In light of the increasing urgency of climate change, this article gives an overview of the state of climate change related litigation in Indonesia during the period of 2010 to 2020. It does so by (1) detecting criminal and civil climate change related cases that have been brought before the courts between the years 2010 and 2020; (2) dissecting examples of case studies; and (3) highlighting the trends, driving factors and impacts of climate change related litigation in Indonesia.

Translation

All of these data bases are in Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian language), so translation was done by the author, in order to have an English language summary of the cases.

Case selection method

My research assistants and I went through the website, using their search engine to identify and pinpoint cases using the phrases of: ‘climate change’, ‘global warming’, ‘greenhouse gasses (GHG) reduction’, ‘microclimate’, ‘macro climate’, ‘mitigation’, and ‘adaptation’ in all court documents available for criminal and civil cases in Indonesian courts (District courts, Appellate courts, and the Supreme Court) that are filed during the period of 2010 to 2020. I chose these phrases because to include a discussion on climate change in a court case, one would have to at least bring about one of these phrases. I did not choose other phrases (for example: fossil fuels, or palm oil) because the case can only be discussing about fossil fuels (or palm oil) without touching upon climate change at all. On the other hand, using the chosen phrases above, directed us to exact cases which use climate change in their court files.

The search engine in the Supreme Court’s directory would let us search one phrase at a time. So we started with ‘climate change’ as our first search phrase, collected the cases, and then continue to our second search phrase: ‘global warming’, then continue with each search phrases as mentioned above. Each case is counted as one case, even though they might contain 2 or 3 of the search phrases. After all the search phrases were inputted, we found 112 (one hundred and twelve) cases which are in relation to climate change litigation. All of these cases are listed in the Supplementary Data 1, submitted together with this article.

Types of disputes and the names of parties

Data was retrieved from the collected court documents. All related cases then are clustered based on their type of case (criminal, civil, administrative, and judicial review). This study focuses on two basic kinds of legal disputes: civil and criminal. In a civil case, one party sues the other, requesting that the court compel them to pay him money or to do or not do something. Damages are monetary awards, while an “injunction” is a directive to carry out or desist from carrying out a certain action. The “plaintiff” is the individual filing the case, while the “defendant” is the party being sued. In a criminal case, there is no plaintiff nor lawsuit. A government prosecutor fills the position of the plaintiff. The prosecutor submits criminal “charges” as opposed to bringing a lawsuit (or, equivalently, “suing” someone). The prosecutor urges the court to punish the defendant by sending them to jail or fining them instead of asking for money damages or an injunction. The accused is referred to as the defendant, exactly like the individual who is being sued in a civil case.

Level of courts

Each type of case was further segmented according to the level of the court involved (district, appeal, or supreme courts). Each case is inputted into an excel spreadsheet, where we identify the types of the case, parties of the case, substance of the case, level of the court, where climate change argument was made in the case, result of the case, and status of the case (Annex-1: Table of Identified Climate Change Related Cases in Indonesia 2010–2020).

This method has error possibility or would fail to detect climate change related case/s if the Supreme Court Directory somehow missed to upload any cases within the time range period (2010–2020).

Case analysis method

This study uses the case law review as its’ methodology. Case law review often referred as a ‘legal case review’ or ‘legal case analysis’, is a process in which legal scholars examine and analyse a specific legal case5. This process involves studying the facts, arguments, legal principles, and outcomes of the studied cases to gain understanding of its significance, implication, and potential impact on the broader legal landscape. This study is a case law review, focusing only on criminal and civil cases6 of climate change related litigation in Indonesia.

Criminal cases were organized into categories based on the defendant, the case’s verdict type, the primary topic of discussion, and where climate change was brought up during the proceeding. In civil cases, cases were categorized based on the type of verdict, plaintiff type (citizen lawsuit, class action, organization, state, or individual claim), level of court (district, appeal, or supreme court), and how climate change had been raised in the case (e.g. as a claim, as a reply, as an argument in the appeal, or in the expert witness argument). To get at the findings and conclusions of the study, data was then verified using additional sources of literature (books, journal articles, and reports from various organizations).

I examine the trends and motivating factors for the use of climate change in court filings, as well as the effects of doing so, based on these cases. To compare annual amounts over a 10-year period for cases that have patterns in the use of climate change in their court pleadings, cases are grouped by year over the 10-year period. These findings are then examined to determine what motivating factors led to the use of “climate change” in court filings. Additionally, based on this, an analysis is conducted to determine the effects of referencing climate change in court documents at the time.

Suitability of case law review method in climate change litigation research

The “case law review method” is a systematic approach to studying and analyzing climate change-related legal cases in the context of climate change litigation research. In a number of respects, this approach complements previous initiatives in climate change litigation research. These are: (1) Jurisprudence: Climate change related litigation often involves novel legal arguments and interpretations. Insights into how courts have handled similar challenges, set precedents, and formed jurisprudence regarding climate change and environmental law can be gained by reviewing earlier cases, which is helpful to researchers.

(2) Identifying trends and patterns: this method allows researchers to identify trends and patterns in how courts have ruled on climate change related cases. This knowledge can help lawyers and advocates adjust their strategy by indicating which claims or arguments have a higher chance of being accepted.

(3) Contribute to strategic decisions making: Research on climate change related lawsuits includes an awareness of the tactics that have worked in the past instances. By analyzing case law, academics can pinpoint persuasive legal justifications on the issue of climate change, proof techniques, and litigation strategies that can direct future work.

(4) Evaluate drivers, impacts and outcomes: this method provides tools to evaluate drivers, impacts, and methods of climate change litigation research. This informs an understanding of the tangible impact of legal actions on climate issues.

(5) Highlight gaps and challenges: through case law review, researchers can identify the gaps and challenges in the legal frameworks, where litigation has been successful or not successful, and challenges faced by parties.

(6) This method also increases transparency and accountability of courts, by analyzing how the courts have handled climate change related litigation cases. It ensures that legal decisions are well-documented and can be reviewed by stakeholders all over the world.

(7) Climate change related litigation research based on case law review contributes to academic scholarship and the broader understanding of how the legal system intersects with environmental and climate issues.

Data availability

Data on cases used and quoted in the study have been deposited in Mendeley Data Repository: Sulistiawati, Linda (2024), “Climate Change Related Litigation in Indonesia 2010–2020”, Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/8djzxvdf3h.1. The data on cases that support the findings of this study is available at https://putusan3.mahkamahagung.go.id/. This data base on all cases processed in Indonesian court since 2011 onwards is hosted by the Indonesian Supreme Court. The author declares that all data supporting the findings of this study are publicly available, and are available within the paper and its supplementary information files. Source data for figure(s) [number(s)] are provided with the paper. Every case in the analysis is current as of August 1, 2023, which is the research’s cutoff date. The Directory- Indonesian Supreme Court Website is the primary resource for this research. It is an official Directory of Verdicts of the Indonesian Supreme Courts, and all other courts under the Supreme Court, they are-- all levels of: Religious Court, Civil Court, Criminal Court, Special Criminal Court, Administrative Court, Special Civil Court, Military Criminal Court, Tax Court, and Justiciability Dispute. The website is organized and maintained by the Indonesian Supreme Court since 2014. As of today, this is the most reliable source of cases of the courts in Indonesia. However, some cases are also uploaded in their original district and high courts’ online directory, some which are available online. We use these district and high courts’ online directories as supplemental source to the supreme court’s directory.

References

Hilson, C. Climate Change: La Riposta del Diritto (Editoriale Scientifica, 2010).

The Hague Court of Appeal, Case 200.178, Urgenda Foundation vs State of the Netherlands (9 October 2018).

United States Federal Court, Case No. 6:15–cv–01517–TC, Juliana vs United States (12 August 2015).

Lahore High Court, Case No. W.P. No. 25501/2015, Asghar Leghari vs Federation of Pakistan (4 September 2015).

Supreme Federal Tribunal, Case No. ADPF 708, PSB et al vs Brazil (11 November 2020).

Macdonagh, E. Brazilian Supreme Court recognises the Paris Agreement as a “human rights treaty”, https://www.cliffordchance.com/insights/resources/blogs/business-and-human-rights-insights/2022/08/brazilian-supreme-court-recognises-the-paris-agreement-as-a-human-rights-treaty.html (2022).

Peel, J. & M. Osofsky, H. Climate Change Related Litigation Regulatory Pathways to Cleaner Energy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Bouwer, K. The unsexy future of climate change related litigation. J. Environ. Law 30, 483–506 (2018).

Watch, S. et. al., Request for Consideration of the Situation of Indigenous Peoples in Kalimantan, Indonesia, under the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination’s Urgent Action and Early Warning Procedures (Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, 2007).

Johnstone, N. Indonesia in the “Redd”: climate change, indigenous peoples and global legal pluralism. Asian‐Pac. Law Policy J. 12, 93–123 (2010).

United Nations Environmental Programme, Global Climate Litigation Report 2023 Status Review (2023).

Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, Indonesia Climate Case Chart 2009–2018, https://climatecasechart.com/non-us-jurisdiction/indonesia/ (2018).

Wibisana, A. & Cornelius, C. Climate change related litigation in Indonesia, in Climate Change Related Litigation in the Asia Pacific (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Wardhana, A. Governing through courts? A gloomy picture of climate litigation in Indonesia. https://voelkerrechtsblog.org/governing-through-courts/ (2022).

Directorate General of Climate Change Control, Enhanced NDC: Indonesia’s Commitment to Contribute More to Maintaining Global Temperature, https://ppid.menlhk.go.id/berita/siaran-pers/6836/enhanced-ndc-komitmen-indonesia-untuk-makin-berkontribusi-dalam-menjaga-suhu-global (2022).

Asshiddiqie, J. Strengthening the Government and Judicial System (Sinar Grafika, 2015).

Bell, G. F. Multiculturalism in law is legal pluralism-lessons from Indonesia, Singapore and Canada. Singap. J. Legal Stud. 315–330 (2006). Retrieved from http://libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/multiculturalism-law-is-legalpluralism-lessons/docview/222725263/se-2.

Indonesia District Court, Case No. 27/PID.B/2013/PN.WTP, Nurung bin Nase, Forestry Crime (2013).

Indonesia District Court, Case No. 94/PID.SUS/2014/PN.TBH, H. Marbawi, Combustion Resulting in Pollution and Damage to Environmental Functions (2014).

Indonesia District Court, Case No. 67/PID.B/2015/PN KLB, Agustinus Letmai and Antonius Letmai, Natural Resource Conservation Crimes (2015).

Indonesia District Court, Case No. 102/PID.SUS-LH/2016/PN WNO, Jumingan Illegal Logging Crime (2016).

Indonesia District Court, Case No. 70/PID.B/LH/2020/PN Spt, Rudiansyah, Negligence Causes Forest Fires (2020).

Indonesia Provincial Court, Case No. 26/PID.B/2014/PT PLK, PT. Menthobi Mitra Lestari, Forestry Crime (2014).

Indonesia District Court, Case No. 143/PID.SUS/2013/PN Rut, Alex Pampur, Illegal Logging Crime (2013).

Indonesia District Court, Case No. 254/PID.SUS/2017/PN PLW, Syahril, Actions that Can Cause Damage to the Environment (2017).

NASA, Earth Observatory, https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/RisingCost/rising_cost5.php (2005).

Syarifah, N. et al. Court Decision Study Report on Environmental Matters (Indonesian Institute for Independent Judiciary, 2020).

Indonesia Supreme Courts, Data on District Court Judges Who Have Been Environmentally Certified as of January 2020, https://badilum.mahkamahagung.go.id/berita/pengumuman-surat-dinas/2895-daftar-hakim-peradilan-umum-yang-telah-memperoleh-sertifikat-lingkungan.html (2020).

Likierman, S. A. The Elements of Good Judgment, https://hbr.org/2020/01/the-elements-of-good-judgment (2020).

Indonesia District Court, Case No. 18/PID.SUS-LH/2016/PN Klk, Gustin Ruddy Narang, Environmental Pollution (2016).

Indonesia District Court, Case No.168/PID.B/LH/2018/PN Pbu, Jumadi, Mining in Forest Areas Without a Ministerial Permit (2018).

Indonesia District Court, Case No.118/PDT.G/LH/2016/PN Plk, Ari Rompas vs Government of Indonesia (Ari Rompas) (2016).

A Saputra, Supreme Court Wins Jokowi, Government Escapes Verdict Against Forest and Land Fires, Supreme Court Wins Jokowi, Government Escapes Verdict Against Forest and Land Fires (detik.com) (2022).

Indonesia District Court, Case No. 91/PDT.G/2017/PN Sel, Sahlan vs President of The Republic of Indonesia (Sahlan) (2017).

Indonesia District Court, Case No. 464/PDT.G/2013/PN.JKT.PST, WALHI vs Government of Indonesia (WALHI) (2013).

Indonesia District Court, Case No.125/PDT.G/LH/2016/PN Bjm, Ministry of Environment and Forestry vs PT. Palmina Utama (Palmina) (2016).

Law No. 32 of 2009 on Environmental Protection and Management (2009).

Indonesia Supreme Court, Case No. 2905 K/PDT/2015, Minister of Environment vs PT Surya Panen Subur (PT Surya Panen Subur) (2015).

Indonesia Provincial Court, Case No. 138/PDT/2015/PT. Smr, Komari vs Mayor of Samarinda (Komari) (2015).

Indonesia District Court, Case No.21/PDT.G/LH/2018/PN Plk, Ministry of Environment and Forestry v PT. Arjuna Utama Sawit (Arjuna) (2018).

Burger, M., Wentz, J. & Horton, R. The law and science of climate change attribution. Columbia J. Environ. Law 45, 60–88 (2020).

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Paris Agreement (2015).

Human Rights Council, Human Rights and Climate Change, Resolution 7/23 (2008).

Human Rights Council, Human Rights and Climate Change, Resolution 10/4 (2009).

Human Rights Council, Human Rights and Climate Change, Resolution 18/22 (2011).

Human Rights Council, Human Rights and Climate Change, Resolution 26/27 (2014).

Human Rights Council, Human Rights and Climate Change, Resolution 29/15 (2015).

Human Rights Council, Human Rights and Climate Change, Resolution 32/33 (2016).

Human Rights Council, Human Rights and Climate Change, Resolution 35/20 (2017).

Human Rights Council, Human Rights and Climate Change, Resolution 38/4 (2018).

Human Rights Council, Human Rights and Climate Change, Resolution 41/21 (2019).

Human Rights Council, Human Rights and Climate Change, Resolution 44/7 (2020).

Human Rights Council, Human Rights and Climate Change, Resolution 47/24 (2021).

Haba, M. R., Yunus, A. & Risal, M. C. Environmental law enforcement through environmental judge certification in Indonesia. J. Crit. Rev. 7, 874–878 (2020).

Indonesia Supreme Court Chief Justice Decision no. 134/KMA/SK/IX/2011 on Environmental Judges Certification, Article 21 (2011).

Rabiali, L. Self-criticism of Environmental NGOs, https://news.detik.com/kolom/d-4908863/otokritik-lsm-lingkungan (2020).

Antlöv, H., Ibrahim R., van Tuijl P. NGO Governance and Accountability in Indonesia: Challenges in a Newly Democratizing Country (2005).

Indonesia Presidencial Regulation No. 5 of 2010 on National Development Medium Term Plan 2010–2014 (2010).

Attachment of Indonesia Presidencial Regulation No. 2 of 2015 on National Development Medium Term Plan 2015-2019 (2015).

National Development Medium Term Plan (Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah) 2020-2024 (2020).

Jong, H. N. Deforestation in Indonesia hits record low, but experts fear a rebound, https://news.mongabay.com/2021/03/2021-deforestation-in-indonesia-hits-record-low-but-experts-fear-a-rebound/ (2021).

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge my host institution the Asia-Pacific Centre for Environmental Law in National University of Singapore Law, Singapore, and my home institution the Faculty of Law Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia, for their support in writing this research. I would also like to thank and greatly appreciate my research assistants for their tireless work in assisting me during the nitty gritty of research and inscription this article, they are: Mochammad Adib Zain (2017–2019), Frendy Tanoto Yoga (2018–2019), Nanda Zyitta Puspitasari (2019–2020), Ibrahim Hanif (2023), and Wibisena Caesario (2023-2024). Without every single one of you I will not be able to complete this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Tracy-Lynn Field and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Martina Grecequet. A peer review file is available in Editorial.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sulistiawati, L.Y. Climate change related litigation in Indonesia. Commun Earth Environ 5, 522 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01684-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01684-1