Abstract

Sea level rise due to anthropogenic warming threatens coastal environments and human societies, but its regional reversibility under successful climate mitigation efforts remains unclear. Here, we investigate sea level fluctuations in the Subpolar North Atlantic using idealized atmospheric carbon dioxide ramp-up and -down experiments. During the ramp-up period, the Subpolar North Atlantic experiences a faster sea level rise than the global mean, followed by a more rapid sea level decline over several dacades with decreasing carbon dioxide. These rapid sea level fluctuations are mainly driven by the response of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation to carbon dioxide forcing. The enhanced meridional salinity transport triggered by the rapid recovery of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation plays a crucial role in the regional sea level decline. Our study highlights the potential for pronounced sea level changes in the Subpolar North Atlantic and surrounding coastal areas under climate mitigation scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Much attention has been paid to the sea level rise as a consequence of global warming, which is primarily attributed to the ocean’s thermal expansion and the melting of glaciers and ice sheets1,2. The Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projected a global mean sea level rise of 0.28 to 0.55 m by 2100 under SSP1-1.9, 0.44 to 0.76 m under SSP2-4.5, and 0.63 to 1.01 m under SSP5-8.5, with the potential to reach 2 m as early as 21503,4. Sea level rise poses challenges to both the natural environment and coastal communities; low-lying coastal areas are highly vulnerable to storm surge-induced flooding, inundation, and erosion from saltwater intrusion, all of which are expected to increase with sea level rise5,6. For example, when Hurricane Sandy struck the east coast of the United States (US) in 2012, it caused over $60 billion in economic losses. 13% of this damage, amounting to $8.1 billion, is attributed to anthropogenic sea level rise, suggesting that it contributes to increased hurricane damage7. Given the environmental and social impacts of sea level rise, accurate projections are essential to help coastal communities and policymakers develop mitigation strategies.

Available observations have shown that sea level rise is not spatially uniform, but rather has a complex spatial pattern8,9,10,11. Regional rates of sea level change due to global warming vary; for example, sea level rise in the western Pacific and western Indian Oceans has been comparatively lower than the global mean from 2006 to 201811. On the other hand, in certain areas, such as the western Pacific, the southeastern Indian Ocean, the Australian Ocean, and the North Atlantic around Greenland, sea level rise is up to three times faster than the global average10,12,13,14. Regional variability in sea level rise has also been projected under enhanced future greenhouse gas emissions. In particular, the Subpolar North Atlantic (SPNA; 45°-65°N, 80°-0°W) is projected to experience a faster sea level rise, exceeding the global average13,15,16, which has been associated with a coincident slowdown of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)13,17,18,19. The AMOC slowdown is accompanied by reduced northward transport of heat and salinity, thereby contributing to the rapid SPNA sea level rise15. Despite large uncertainties, state-of-the-art climate models generally agree that global warming weakens the AMOC20,21,22. This, in turn, is consistent with the more rapid sea level rise in the SPNA than that of the global mean15,18,23,24. Major coastal cities in the US, such as New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, are characterized by both dense populations and high gross domestic product25. Therefore, it is not surprising that past and future sea level changes in the SPNA have received attention18,19,26,27,28. It is important to note that there is uncertainty in the temporal and spatial patterns of sea level responses to the AMOC slowdown, with considerable variability depending on the model used19.

At the same time, concerns have been raised about the achievability of the Paris Agreement goals29,30, leading to growing attention to the question of whether anthropogenic climate change can be reversed by CO2 removal within the human-relevant time scales (i.e., centennial scale). Specifically, from a global mean perspective, both surface temperature and precipitation are largely reversible within a century following the CO2 increase and subsequent decrease31,32,33,34. However, several subsystems are expected to exhibit nonlinear responses to CO2 removal; a notable example is the AMOC (Fig. 1a). As CO2 levels rise, the strength of the AMOC weakens. Interestingly, even after CO2 levels stabilize or begin to decrease, the AMOC continues to weaken. Once the AMOC begins to recover, it does so at a faster rate than it initially weakened, eventually exceeding its original strength—a phenomenon known as AMOC overshoot35,36. These time-delayed responses of the climate system to changes in external forcing, such as CO2 concentration, are referred to as hysteresis. Considering the aforementioned tight relationship between the SPNA sea level and the AMOC, we can hypothesize that SPNA sea level would also exhibit a unique nonlinear response to CO2 removal. Indeed, Sigmond et al.24 have shown that even after anthropogenic emissions are set to zero, both global mean and SPNA sea level continue to rise for a while, albeit at a slower rate in the SPNA compared to the global mean. This naturally raises a question of whether atmospheric CO2 reductions can effectively restore the already-increased SPNA sea level to its original level. Because hazards associated with sea level rise, such as inundation, are highly localized and do not occur globally, a regional approach to sea level reversibility is needed; previous studies have generally addressed this from a global mean perspective31,32,37,38,39. The regional approach can make studies considering sea level reversibility more practical and help to develop effective future mitigation strategies.

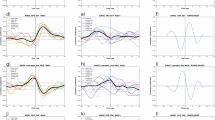

a Annual mean sea level anomalies for 28 ensemble members, showing the global mean (navy) and the SPNA (red). The time series are running averaged with an 11-year window, subtracting the initial value. The green line represents the temporal evolution of the anomalous AMOC strength with respect to the initial value. The AMOC strength is defined as the average of the annual mean Atlantic meridional stream function from 35°N to 45°N at 1000 m. The gray line is the CO2 concentration. The vertical line indicates where the corresponding global mean sea level is maximized (dashed navy), while the dashed green vertical line is for the maximum AMOC. The rising period covers from the initial year (years 0–10) to the global mean sea level maximum year (years 221–231; navy vertical line). The recovery period is defined from the end of the rising period to the AMOC maximum year (years 308–318; green vertical line). Ensemble mean sea level response during the rising (b; the value in years 221–231 is subtracted from the years 0–10), and the recovery period (c; the value in years 308–318 is subtracted from years 221–231). Only anomalies that are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level are shown.

In this study, we therefore investigate the spatio-temporal evolution of sea level, especially in the SPNA, and the underlying mechanisms under the idealized CO2 ramp-up and -down scenario using a climate model. We found pronounced SPNA sea level fluctuations characterized by 1.5 times faster sea level rise and 4.5 times faster sea level decline than the global mean in response to CO2 forcing. Its regional patterns are driven by the radiative forcing and associated AMOC dynamics. This study highlights the importance of AMOC projections in predicting and proactively responding to sea level changes in the SPNA.

Results

We first examine the global mean sea level response to an increase and subsequent decrease in atmospheric CO2 concentration using the climate model simulation integrated about 500 years (Fig. 1). As the employed model (CESM1) does not include interactive land-based ice model, the global mean sea level response is solely attributed to the ocean thermal expansion (navy line in Fig. 1a). The CO2 forcing is designed to peak in year 140, while the global mean sea level peaks in about years 221–231. After the peak, the global mean sea level slowly declines, but does not return to 50% of the its maximum until the end of the simulation, indicating a clear irreversibility of sea level37,39.

Sea level increases and decreases unevenly in response to the CO2 forcing (Fig. 1b, c, and Supplementary Fig. 1). For example, during the rising period, defined as the period from the beginning (years 0–10) to the year of maximum sea level (years 221–231), the Southern Ocean exhibits a relatively small sea level rise compared to that of the global mean, appearing as a band south of 50°S (Figs. 1b and S1). The small sea level rise in the Southern Ocean is largely induced by the poleward shift of westerlies in the Southern Hemisphere15,40,41,42. The regional sea level in this region continues to rise during the recovery period, defined as the period from the year of maximum sea level (years 221–231) to the year of maximum AMOC strength (years 308–318) (Fig. 1c). Meanwhile, of particular interest for climate change mitigation are the large sea level changes in the SPNA (Fig. 1b, c, and Supplementary Fig. 1). The SPNA sea level shows a much more substantial temporal evolution than the global average (red line in Fig. 1a). It is projected to rise by up to 0.9 m, with the rate of increase during the rising period approximately 1.5 times larger than the global mean. In the recovery period, it decreases at a rate of 0.64 m per 100 years, about 4.5 times faster than the global mean, which declines at a rate of 0.14 m per 100 years. Due to this rapid decline, the SPNA sea level is expected to fall below the global mean around the year 283, approximately 73 years after its peak. This notable change in the SPNA sea level is associated with the AMOC response to CO2 forcing.

The AMOC exhibits a clear hysteresis with respect to changes in atmospheric CO2 (green line in Fig. 1a). Both surface warming18,20,43 and freshwater input from the Arctic sea ice loss and changes in hydrological cycle44,45 reduce upper ocean density and consequently weaken the AMOC. The weakened AMOC corresponds to a reduction in the northward heat and salt transport from the subtropical Atlantic, thereby strengthening the meridional temperature and salinity gradient in the Atlantic46. This, in turn, creates a warming deficit region under the global warming, known as the North Atlantic warming hole21,44. Furthermore, the enhanced meridional salinity gradient boosts the AMOC recovery when CO2 returns, even leading to the AMOC overshoot, where the AMOC strength becomes anomalously stronger35,36,47,48. Note that the AMOC overshoot is also observed in most of CMIP6 models based on CDRMIP protocol (Supplementary Fig. 4a), however, it has been reported that some models do not simulate the AMOC overshoot49. The timing of the AMOC overshoot coincides with the time when the SPNA sea level is no longer decreasing (Fig. 1a), indicating the tight relationship between the AMOC and the SPNA sea level. Although it is important to understand the responses of the SPNA sea level pattern and its mechanism with the CO2 removal, it has not been as widely studied as those with increasing atmospheric CO2. Therefore, we further investigate both the patterns on SPNA sea level increases and decreases associated with the ramp-up and -down CO2 experiment.

The SPNA sea level rise and fall consistently show a skew to the northwest of the SPNA (Fig. 2a, b). This asymmetric pattern is closely linked to the evolution of the AMOC (Fig. 1a). During the rising period, the weakening of the AMOC is accompanied by a slowdown of both deep convection in the Labrador Sea and the subpolar gyre13,50. The reduction in deep convection reduces the density-driven sinking process, while the weakening of the subpolar gyre can generate anomalous anticyclonic ocean circulation (Fig. 2a). Both contribute to an increase in water mass within the subpolar gyre, thereby contributing to sea level rise in this region larger than the global mean. During the recovery period, both the deep convection and the subpolar gyre are restored, resulting in a subsequent decrease in sea level (Fig. 2b). This spatial pattern contributes to a substantial change in sea level along the east coast of the US and Canada, particularly north of 35°N (Fig. 2c). Major cities along the northeast coast of the US are expected to suffer considerable damage from rapid sea level fluctuations in the SPNA. Because the SPNA sea level is climatologically low due to the maintenance of strong and narrow Gulf Stream and North Atlantic currents18,26, the rapid SPNA sea level rise could make surrounding areas more vulnerable to the increased hazards of flooding and inundation51,52.

Anomalous sea level (shading) and top 50 m averaged ocean currents (arrows) in the SPNA for the rising period (a; years 221–231 minus years 0–10), and the recovery period (b; years 308–318 minus years 221–231). The green line indicates the leftmost ocean grids at each latitude in the North Atlantic Ocean. The major cities along the US east coast are represented by colored circles such as New York (green), Boston (yellow), Philadelphia (pink), Washington (blue), Jacksonville (orange), and Miami (red). c Hovmöller diagram of the sea level in the green coastline. All of the figures show the mean of the 28 ensembles. Only values that are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level are shown.

To better understand the evolution of the SPNA sea level, we next breakdown it into contributions from density changes, further separated into temperature and salinity, and mass redistribution. The steric sea level attributed to the density variation exhibits substantial changes north of 45°N, similar to the sea level patterns (Fig. 3a, b vs. 2a, b). Changes in the steric sea level are related to the mean depth of the ocean basins from sea level to the ocean floor15. Given an equal decrease (increase) in ocean density, steric sea level rise (decline) is more pronounced in the deeper ocean compared to the shallower ocean, resulting in small changes in steric sea level for shallower regions like continental shelf. This horizontal gradient of the steric sea level change induces mass redistribution from the open ocean to the surrounding areas, the so-called mass redistribution-induced sea level changes2,15,53,54. Indeed, steric sea level rise in the SPNA (Fig. 3a) is accompanied by sea level rise on the continental shelf (Fig. 3c) and vice versa (Fig. 3b, d). The sea level changes resulting from the mass redistribution have a major impact on sea level rise (or fall) along the heavily populated coasts of North America (Fig. 2c).

Anomalous SPNA sea level decomposed into the steric sea level (a, b), the mass redistribution-induced sea level (c, d), the thermosteric (e, f), and the halosteric (g, h). The left column is for the rising period (years 221–231 minus years 0–10) and the right column is for the recovery period (years 308–318 minus years 221–231). All figures show the average of the 28 ensembles, and only the values that are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level are shown.

The steric sea level changes can be further divided into thermal and saline contributions, thermosteric sea level (Fig. 3e, f) and halosteric sea level (Fig. 3g, h), respectively. From here on, we will simply refer to them as thermosteric and halosteric. Both exhibit a distinct latitudinal dipole pattern relative to 50°N (Fig. 3f–h), except for the rising period of thermosteric with the negligible thermosteric increase north of 50°N (Fig. 3e). The two steric components show an opposite sign and therefore cancel each other out. The SPNA steric sea level changes are dominated by different factors depending on the latitude relative to 50°N (Fig. 3a, b). For instance, the steric sea level rise is dominated by the halosteric effect north of 50°N, while the thermosteric effect dominates south of 50°N (Fig. 3a)15. Indeed, the rapid SPNA sea level decline during the recovery period is largely explained by the halosteric drop (Fig. 4a). To understand why this latitudinal dipole pattern occurs and why there is an exception in the thermosteric response during the rising period, we investigate the changes in heat and salinity in the SPNA in response to CO2 increase and decrease.

a Annual mean anomalies for 28 ensemble mean SPNA sea level (red; same as in Fig. 1a), SPNA thermosteric (orange), SPNA halosteric (purple), and the prescribed CO2 forcing (gray). Each thin colored line represents individual ensemble members. The dashed vertical line indicates the year of maximum global mean sea level (navy) and AMOC (green). Ensemble mean Hovmöller diagram of the Atlantic basin for zonal mean steric sea level (b), thermosteric (c), and halosteric (d). The dashed vertical line indicates the end of the rising period, which is also the beginning of the recovery period, and the end of the recovery period, respectively.

The heat and salinity changes in the SPNA can be explained by the radiative forcing effect and the resultant AMOC alteration (Supplementary Fig. 3). During the rising period, the suppressed meridional heat redistribution caused by the AMOC weakening increases the thermosteric south of 50°N and decreases the thermosteric north of 50°N (Figs. 3e, 4c, and Supplementary Fig. 3a), while the suppressed salt redistribution decreases the halosteric south of 50°N and increases the halosteric north of 50°N (Figs. 3g, 4d, and Supplementary Fig. 3b). Hence, the dipole pattern could be largely explained by the AMOC response. However, it is noteworthy that the radiative forcing directly induces the thermal expansion of the global ocean, leading to increased thermosteric throughout the North Atlantic (Figs. 3e, 4c, and Supplementary Fig. 3a); therefore, the meridional dipole pattern is not clear in the thermosteric during the rising period due to the cancellation of global ocean warming and AMOC weakening (Fig. 3e). Meanwhile, during the recovery period, in response to both the global ocean cooling and the AMOC strengthening (Fig. 1a), changes in the steric sea level occur in exactly opposite way to those shown in the rising period (Figs. 3, 4 and Supplementary Fig. 3). After the AMOC intensity returns to its initial level (Fig. 1a), the SPNA thermosteric decreases and the halosteric increases again (Fig. 4). The distinct response of the thermosteric and halosteric caused by the AMOC hysteresis results in a more rapid sea level fluctuation in the SPNA (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 2).

So far, we have shown the rapid sea level rise and subsequent fall in the SPNA as a consequence of the hysteresis behavior of the AMOC along with the influence of global warming. To support our findings, we further investigate the inter-ensemble spread of the AMOC and the SPNA sea level. There is a statistically significant negative relationship between 28 ensemble members, that an ensemble member with a weaker AMOC corresponds to an ensemble with a larger SPNA sea level rise during the rising period (Fig. 5a). This relationship consistently holds for the recovery period (Fig. 5b). The spatial patterns from the inter-ensemble regression between AMOC strength and sea level also confirm the clear negative relationship in the SPNA region (Fig. 5c, d), although the detailed pattern is somewhat different from the local patterns of the corresponding SPNA sea level (Fig. 2a, b). The spatially skewed pattern is shown only in Fig. 2a, b, which is particularly important for the coastline. This may highlight that not only the AMOC but also global warming influences the actual local pattern of the SPNA sea level. Thus, the consideration of both factors becomes important and emphasizes the crucial role of the AMOC in the rapid sea level rise and decline of the SPNA.

Inter-ensemble relationship between AMOC strength and SPNA sea level for the rising (a), and the recovery period (b). The inter-ensemble regression maps of the North Atlantic sea level onto AMOC strength during the rising (c), and the recovery period (d). Only statistically significant values, evaluated by Student’s t-test at the 95% confidence level, are shown.

Discussion

In this study, based on the climate model simulation, we examine sea level changes in response to CO2 ramp-up and –down forcing, particularly in the SPNA, which is known to exhibit a faster sea level rise than the global mean in a warming climate. Consistent with previous study24, the SPNA sea level also declines faster relative to the global mean in the transient CO2 reversibility experiment, demonstrating its sensitivity to changes in CO2 levels. The rapid sea level decline in the recovery period is strongly related to both the reduced ocean thermal expansion due to mitigated global warming and the changes in meridional redistribution of the heat and salt resulting from the AMOC hysteresis. The dominant process is the restoration of the northward transport of heat and salinity by the recovery and overshoot of the AMOC, confirming the previous studies24,36. In particular, the halosteric mainly controls the SPNA steric sea level changes, especially the fast drop of the SPNA sea level during the recovery period, indicating the key role of salinity23,24,55. This study emphasizes that we need to consider the response of the ocean circulation to the CO2 forcing as well as the ocean thermal expansion/contraction when it comes to the sea level changes in the SPNA region. While these results are generally consistent with earlier research24,36, our study builds on this understanding by providing a more detailed breakdown of the factors contributing to sea level changes, both spatially and temporally. In other words, we emphasize not only the sea level hysteresis but also each contribution for sea level change in both spatial and temporal perspectives.

One of the major drivers of sea level rise is mass input from the land, which accounts for about 60% of the current sea level rise2, but is not included in the model. In particular, the Greenland Ice Sheet has experienced increasing mass loss in recent decades, with observational estimates indicating a loss of about 171 ± 157 Gt year−1 (equivalent to ~0.005 Sv) and an acceleration of the mass loss of 16.8 ± 2.8 Gt year−2 56. Projections indicate that this trend will continue and even intensify in the coming centuries57,58. Thus, the potential melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet may have substantial impacts on the changes in the SPNA sea level by altering the SPNA density itself and AMOC-induced heat and salinity redistribution. Furthermore, the Greenland Ice Sheet may show strong hysteresis behavior in response to CO2 reduction. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the interactive land-based ice process, including the Greenland Ice Sheet for more accurate global and SPNA sea level changes in potential climate mitigation scenarios in a future study.

Our findings underscore that the northeastern coast of North America is one of the most susceptible regions to intense sea level fluctuations and ocean circulation changes in response to changing CO2 emissions. Many studies have already shown that US coastal cities such as New York59,60, Boston61, are highly vulnerable to inundation and flooding caused by sea level rise, resulting in economic losses62. This vulnerability arises from the response of the ocean circulation to the CO2 forcing, as well as the ocean steric expansion, as discussed earlier.

Given the potential unrealistic aspects of the quadrupled CO2 ramp-up and -down scenario, we also conducted a similar analysis using a more moderate two-fold CO2 ramp-up and -down scenario (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8). The results show consistent patterns of rapid sea level rise and decline in the SPNA, as well as similar changes in heat and salinity in the Atlantic, driven by changes in the AMOC and radiative forcing. This result shows that the rapid sea level changes in the SPNA may occur under a low-end emissions scenario. It should be noted, however, that our simulations are initialized from a present-day state rather than the more common pre-industrial baseline. This initialization may not fully capture climate system responses to historical warming from pre-industrial to present-day. To address this potential limitation and ensure the robustness of our results, we further replicated these analyses using CMIP6 models based on the CDRMIP protocol, which was branched from the pre-industrial baseline (Supplementary Figs. 4–6). The results are consistent with our main findings, suggesting that our results are not dependent on both initializing from the present-day state and single model.

While achieving a 1% annual reduction in CO2 may be challenging and perhaps unrealistic in practical terms, it is encouraging that the SPNA has the potential for rapid sea level recovery with any meaningful CO2 reduction. Therefore, it becomes crucial to continue and enhance global CO2 mitigation efforts, as these actions are likely to have a more pronounced impact in the SPNA region, where sea level is particularly sensitive to CO2 concentrations. Specifically, the magnitude of sea level rise in this region is observed to be 1.5 times greater than the global mean, with the potential for reversal being 4.5 times faster. Although these specific numbers are derived from an idealized experiment and may not represent exact real-world values, they demonstrate how effective CO2 reduction efforts can lead to a rapid reversal of the sea level rise in the SPNA.

Methods

Model and experiments

We used the Community Earth System Model, Version 1.2 (CESM1.2)63, which includes the Community Atmospheric Model Version 5 (CAM5), the Community Land Model Version 4 (CLM4), the Community Ice Code Version 4 (CICE4), and the Parallel Ocean Version 2 (POP2). CAM5 and CLM4 have a horizontal resolution of ~1°x1° and 30 vertical levels64. The CICE4 and POP2 have 60 vertical levels, with a longitudinal resolution of 1° (the latitudinal resolution was ~1/3° near the equator and gradually increased to ~1/2° near the poles)65.

We performed two types of idealized climate model simulations. First, we integrated a 900-year long present-day control experiment with an atmospheric CO2 concentration of 367 ppm. We then conducted a CO2 ramp-up and ramp-down experiment for 500 years, branching from the 28 different initial conditions from the present-day control. The CO2 concentration is increased by 1 % yr−1 for the first 140 years to quadruple the concentration (1468 ppm). It is then decreased symmetrically for another 140 years, so that the concentration recovers to its original level (367 ppm). Finally, we integrated an additional 220 years with the original CO2 level. Note that this experimental design is quite similar to the protocol of the Carbon Dioxide Removal Model Intercomparison Project (or CDRMIP; Keller et al., 2018)66, except for the initially set CO2 level. To obtain robust results, a total of 28 ensemble simulations were performed with different initial conditions.

Sea level calculation and decomposition

To understand the processes behind sea level changes, we introduce the sea surface height (SSH) tendency equation under hydrostatic balance, which is decomposed into density and mass contributions18,67,68:

where \(H\) is the water depth, \(\Delta {\rm{p}}\) is the difference between surface and bottom pressure, \(g\) is the gravitational acceleration, \(\rho\) is the in-situ seawater density, and \({\rho }_{0}\) is the constant reference density, which is the initial reference state (e.g., the initial state of a ramp-up scenario). The steric tendency results from changes in the regional density integrated over the water column. The mass tendency is combined by mass fluxes crossing outside of the ocean and the convergence of barotropic mass transport69.

Like most state-of-the-art models, the employed model could not simulate mass fluxes resulting from glaciers and ice sheet melting, so the mass tendency is purely a result of barotropic mass redistribution (i.e., the globally averaged mass tendency is zero by definition). At the same time, POP2 employs the Boussinesq approximation, a common approximation in ocean models that conserves volume rather than mass70,71,72. This approximation does not account for sea level changes associated with the net expansion or contraction of the global ocean (i.e., the globally averaged steric tendency set to be zero by approximation). Hence, by replacement of the time tendencies with temporal increments \((\delta )\), Eq. (1) could be rendered as

which state that, without additional mass injection into the ocean, the anomalous SSH is attributed to regional density changes (\({h}_{{\rm{S}}}^{{\prime} }\) is the local steric sea level) and barotropic mass redistribution (\({h}_{{\rm{T}}}^{{\prime} }\) is the mass redistribution-induced sea level) caused by \({h}_{{\rm{S}}}^{{\prime} }\) (\({\prime}\) is the deviation from the global mean). In the absence of bottom pressure data from the POP2 output, we estimate the mass redistribution term by calculating the remainder between the SSH and the local steric sea level.

Although Eq. (2) well explains the sea level response to climate change12, the ocean model based on the Boussinesq approximation does not reflect the global mean sea level changes due to thermal expansion (or contraction). It is worth noting that the global mean sea level change due to salinity change is considered to be zero73,74. To address the limitation of the Boussinesq approximation, Greatbatch (1994)70 proposed to add a globally uniform time-dependent correction to the Boussinesq sea level at each grid point. The “corrected” sea level from a Boussinesq model evolves according to the following equation68:

To incorporate the global steric effect, which is missing in the Boussinesq model, the new term in Eq. (3) is given by (Griffies and Greatbatch, 2012)68

where the 〈〉 denotes the global mean, \(V\) is the volume of liquid seawater in the global ocean (\({\int }_{\!\!globe}dA{\int }_{\!\!-H}^{\eta }dz\)) and A is the global ocean surface area (\(A={\int }_{\!\!globe} \, dA={\int }_{\!\!globe}dxdy\)). Using the approximation in Eq.(4), the global mean non-Boussinesq steric effect is equal to the global steric effect \((\delta \bar{{h}_{{\rm{s}}}})\) assuming no net change in ocean mass. Therefore, Eq. (3) can be rewritten as

which allows us to practically account for sea level changes in the context of models based on the Boussinesq approximation. According to the Griffies and Greatbatch et al.68, this approximation uses time-mean density fields to compute the time tendency, along with either a time-mean volume.

The steric sea level \({h}_{{\rm{S}}}\) can be further divided into contributions from temperature and salinity, referred to as thermosteric sea level (thermosteric) and halosteric sea level (halosteric), respectively18,74. Thermosteric and halosteric are approximated by the following equations, respectively:

where \({T}_{{\rm{R}}}\), \({S}_{{\rm{R}}}\), \({p}_{{\rm{R}}}\) and \({\eta }_{{\rm{R}}}\) are the temperature, salinity, pressure, and sea level for the reference state.

Significance testing

To test the statistical significance of the ensemble mean difference compared to the initial condition during the rising and recovery periods, we performed a bootstrap analysis using the difference compared to the initial condition of 28 ensemble members. At each grid point, 10,000 bootstrap samples were generated by randomly sampling 28 ensemble members with replacement. A grid point was considered statistically significant if the 97.5th percentile and the 2.5th percentile of the bootstrap samples have the same sign, corresponding to a 95% confidence level.

Data availability

The data used in this study are be available from https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25340890.v6 (ref. 75), and the CMIP6 archives are freely available from https://esgf-node.llnl. gov/projects/cmip6.

Code availability

The codes used in this study are be available from https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25340890.v6 (ref. 75). All figures were generated by using software package Python with the matplotlib and basemap modules (https://matplotlib.org/, https://matplotlib.org/basemap/).

References

WCRP Global Sea Level Budget Group. Global sea-level budget 1993–present. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 1551–1590 (2018).

Frederikse, T. et al. The causes of sea-level rise since 1900. Nature 584, 393–397 (2020).

Ming, A. et al. Key Messages from the IPCC AR6 Climate Science Report. https://www.cambridge.org/engage/coe/article-details/617a83eb45f1eea41b40a461,https://doi.org/10.33774/coe-2021-fj53b (2021).

Ng, T., Gangadharan, N., Moise, A. F. & Palmer, M. Past and future sea level change. V3 Science Report, Chapter 12, Meteorological Service Singapore, National Environment Agency. Available at https://www.mss-int.sg/docs/defaultsource/v3_reports/v3_science_report/v3_science_report_chapter_12-amended.pdf (2024).

Nicholls, R. J. et al. Sea-level rise and its possible impacts given a beyond 4C world in the twenty-first century. Philosop. Transact. R. Soc. A: Mathe. Phys. Eng. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2010.0291 (2011).

De Dominicis, M., Wolf, J., Jevrejeva, S., Zheng, P. & Hu, Z. Future interactions between sea level rise, tides, and storm surges in the World’s Largest Urban Area. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087002 (2020).

Strauss, B. H. et al. Economic damages from Hurricane Sandy attributable to sea level rise caused by anthropogenic climate change. Nat. Commun. 12, 2720 (2021).

Douglas, B. C. Sea level change in the era of the recording tide gauge. in International Geophysics Vol. 75 37–64 (Elsevier, 2001).

Bindoff, N. L. et al. Observations: oceanic climate change and sea level. in (eds. Solomon, S. et al.) 385–428 (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Cazenave, A. & Llovel, W. Contemporary sea level rise. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2, 145–173 (2010).

Hamlington, B. D., Frederikse, T., Nerem, R. S., Fasullo, J. T. & Adhikari, S. Investigating the acceleration of regional sea level rise during the satellite altimeter era. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086528 (2020).

Bordbar, M. H., Martin, T., Latif, M. & Park, W. Effects of long-term variability on projections of twenty-first century dynamic sea level. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 343–347 (2015).

Lyu, K., Zhang, X. & Church, J. A. Regional dynamic sea level simulated in the CMIP5 and CMIP6 models: mean biases, future projections, and their linkages. J. Clim. 33, 6377–6398 (2020).

Nerem, R. S. & Hamlington, B. D. Satellite Measurements of Sea Level Change: Past, Present, and Future. in 2024 IEEE Aerospace Conference 1–4 (IEEE, Big Sky, MT, USA, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/AERO58975.2024.10521318.

Yin, J., Griffies, S. M. & Stouffer, R. J. Spatial variability of sea level rise in twenty-first century projections. J. Clim. 23, 4585–4607 (2010).

Yin, J. Century to multi-century sea level rise projections from CMIP5 models: SEA LEVEL RISE PROJECTION. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L17709 (2012).

Levermann, A., Griesel, A., Hofmann, M., Montoya, M. & Rahmstorf, S. Dynamic sea level changes following changes in the thermohaline circulation. Clim. Dyn. 24, 347–354 (2005).

Yin, J., Schlesinger, M. E. & Stouffer, R. J. Model projections of rapid sea-level rise on the northeast coast of the United States. Nat. Geosci. 2, 262–266 (2009).

Little, C. M. et al. The relationship between U.S. east coast sea level and the atlantic meridional overturning circulation: a review. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124, 6435–6458 (2019).

Collins, M. et al. Long-term climate change: projections, commitments and irreversibility. In Climate Change 2013 - The Physical Science Basis: Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 1029–1136 (Cambridge University Press, 2013)

Caesar, L., Rahmstorf, S., Robinson, A., Feulner, G. & Saba, V. Observed fingerprint of a weakening Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation. Nature 556, 191–196 (2018).

Weijer, W., Cheng, W., Garuba, O. A., Hu, A. & Nadiga, B. T. CMIP6 models predict significant 21st Century decline of the atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086075 (2020).

Körper, J., Spangehl, T., Cubasch, U. & Huebener, H. Decomposition of projected regional sea level rise in the North Atlantic and its relation to the AMOC. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L19714 (2009).

Sigmond, M., Fyfe, J. C., Saenko, O. A. & Swart, N. C. Ongoing AMOC and related sea-level and temperature changes after achieving the Paris targets. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 672–677 (2020).

Kummu, M., Taka, M. & Guillaume, J. H. A. Gridded global datasets for Gross Domestic Product and Human Development Index over 1990–2015. Sci. Data 5, 180004 (2018).

Sallenger, A. H., Doran, K. S. & Howd, P. A. Hotspot of accelerated sea-level rise on the Atlantic coast of North America. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 884–888 (2012).

Yin, J. & Goddard, P. B. Oceanic control of sea level rise patterns along the East Coast of the United States: U.S. EAST COAST SEA LEVEL RISE. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 5514–5520 (2013).

Bouttes, N., Gregory, J. M., Kuhlbrodt, T. & Smith, R. S. The drivers of projected North Atlantic sea level change. Clim. Dyn. 43, 1531–1544 (2014).

Allen, M. R. et al. Warming caused by cumulative carbon emissions towards the trillionth tonne. Nature 458, 1163–1166 (2009).

Lamboll, R. D. et al. Assessing the size and uncertainty of remaining carbon budgets. Nat. Clim. Chang. 1–8 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01848-5 (2023).

Boucher, O. et al. Reversibility in an Earth System model in response to CO2 concentration changes. Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 024013 (2012).

Wu, P., Ridley, J., Pardaens, A., Levine, R. & Lowe, J. The reversibility of CO2 induced climate change. Clim. Dyn. 45, 745–754 (2015).

Jeltsch-Thömmes, A., Stocker, T. F. & Joos, F. Hysteresis of the Earth system under positive and negative CO2 emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 124026 (2020).

Kug, J.-S. et al. Hysteresis of the intertropical convergence zone to CO2 forcing. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 47–53 (2022).

Jackson, L. C., Schaller, N., Smith, R. S., Palmer, M. D. & Vellinga, M. Response of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation to a reversal of greenhouse gas increases. Clim. Dyn. 42, 3323–3336 (2014).

Wu, P., Jackson, L., Pardaens, A. & Schaller, N. Extended warming of the northern high latitudes due to an overshoot of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation: AMOC OVERSHOOT. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L24704 (2011).

Bouttes, N., Gregory, J. M. & Lowe, J. A. The reversibility of sea level rise. J. Clim. 26, 2502–2513 (2013).

Zickfeld, K. et al. Long-term climate change commitment and reversibility: an EMIC intercomparison. J. Clim. 26, 5782–5809 (2013).

Ehlert, D. & Zickfeld, K. Irreversible ocean thermal expansion under carbon dioxide removal. Earth Syst. Dyn. 9, 197–210 (2018).

Saenko, O. A., Fyfe, J. C. & England, M. H. On the response of the oceanic wind-driven circulation to atmospheric CO2 increase. Clim. Dyn. 25, 415–426 (2005).

Stouffer, R. J. et al. Investigating the causes of the response of the thermohaline circulation to past and future climate changes. J. Clim. 19, 1365–1387 (2006).

Bouttes, N., Gregory, J. M., Kuhlbrodt, T. & Suzuki, T. The effect of windstress change on future sea level change in the Southern Ocean: effect of windstress on future sea level. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L23602 (2012).

Gregory, J. M. et al. The Flux-Anomaly-Forced Model Intercomparison Project (FAFMIP) contribution to CMIP6: investigation of sea-level and ocean climate change in response to CO2 forcing. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3993–4017 (2016).

Rahmstorf, S. et al. Exceptional twentieth-century slowdown in Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 475–480 (2015).

Thorpe, R. B., Gregory, J. M., Johns, T. C., Wood, R. A. & Mitchell, J. F. B. Mechanisms determining the Atlantic thermohaline circulation response to greenhouse gas forcing in a non-flux-adjusted coupled climate model. J. Clim. 14, 3102–3116 (2001).

Bryden, H. L., King, B. A., McCarthy, G. D. & McDonagh, E. L. Impact of a 30% reduction in Atlantic meridional overturning during 2009–2010. Ocean Sci. 10, 683–691 (2014).

An, S. et al. Global Cooling Hiatus Driven by an AMOC overshoot in a carbon dioxide removal scenario. Earth’s Future 9, e2021EF002165 (2021).

Oh, J.-H., An, S.-I., Shin, J. & Kug, J.-S. Centennial memory of the Arctic Ocean for future Arctic climate recovery in response to a carbon dioxide removal. Earth's Future 10, e2022EF002804 (2022).

Krasting, J. P. et al. Role of ocean model formulation in climate response uncertainty. J. Clim. 31, 9313–9333 (2018).

Sgubin, G., Swingedouw, D., Drijfhout, S., Mary, Y. & Bennabi, A. Abrupt cooling over the North Atlantic in modern climate models. Nat. Commun. 8, 14375 (2017).

Linhoss, A. C., Kiker, G., Shirley, M. & Frank, K. Sea-level rise, inundation, and marsh migration: simulating impacts on developed lands and environmental systems. J. Coastal Res. 31, 36 (2015).

Sweet, W. V., Genz, A. S., Obeysekera, J. & Marra, J. J. A regional frequency analysis of tide gauges to assess pacific coast flood risk. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 581769 (2020).

Dangendorf, S. et al. Data-driven reconstruction reveals large-scale ocean circulation control on coastal sea level. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 514–520 (2021).

Wang, O. et al. Local and remote forcing of interannual sea‐level variability at Nantucket Island. JGR Oceans 127, e2021JC018275 (2022).

Antonov, J. I., Levitus, S. & Boyer, T. P. Steric sea level variations during 1957–1994: Importance of salinity. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 107, SRF 14-1-SRF 14-8 (2002).

van den Broeke, M. R. et al. On the recent contribution of the Greenland ice sheet to sea level change. Cryosphere 10, 1933–1946 (2016).

Seroussi, H. et al. ISMIP6 Antarctica: a multi-model ensemble of the Antarctic ice sheet evolution over the 21st century. Cryosphere 14, 3033–3070 (2020).

Edwards, T. L. et al. Projected land ice contributions to twenty-first-century sea level rise. Nature 593, 74–82 (2021).

Gornitz, V., Couch, S. & Hartig, E. K. Impacts of sea level rise in the New York City metropolitan area. Glob. Planetary Change 32, 61–88 (2001).

Wang, Y. & Marsooli, R. Dynamic modeling of sea-level rise impact on coastal flood hazard and vulnerability in New York City’s built environment. Coastal Eng. 169, 103980 (2021).

Kirshen, P., Knee, K. & Ruth, M. Climate change and coastal flooding in Metro Boston: impacts and adaptation strategies. Clim. Change 90, 453–473 (2008).

Leatherman, S. P. Chapter 8 Social and economic costs of sea level rise. Int. Geophys. 75, 181–223 (2001).

Hurrell, J. W. et al. The community earth system model: a framework for collaborative research. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 94, 1339–1360 (2013).

Neale, R. B. et al. Description of the NCAR community atmosphere model (CAM 5.0). NCAR Tech. Note NCAR/TN-486+ STR 1, 1–12 (2010).

Smith, R. et al. The parallel ocean program (POP) reference manual ocean component of the community climate system model (CCSM) and community earth system model (CESM). LAUR-01853 141, 1–140 (2010).

Keller, D. P. et al. The Carbon Dioxide Removal Model Intercomparison Project (CDRMIP): rationale and experimental protocol for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 1133–1160 (2018).

Gill, A. E. & Niller, P. P. The theory of the seasonal variability in the ocean. Deep Sea Res. Oceanogr. Abstracts 20, 141–177 (1973).

Griffies, S. M. & Greatbatch, R. J. Physical processes that impact the evolution of global mean sea level in ocean climate models. Ocean Modell. 51, 37–72 (2012).

Griffies, S. M. et al. An assessment of global and regional sea level for years 1993–2007 in a suite of interannual CORE-II simulations. Ocean Modell. 78, 35–89 (2014).

Greatbatch, R. J. A note on the representation of steric sea level in models that conserve volume rather than mass. J. Geophys. Res. 99, 12767–12771 (1994).

Meyssignac, B. et al. Causes of the Regional Variability in Observed Sea Level, Sea Surface Temperature and Ocean Colour Over the Period 1993–2011. in Integrative Study of the Mean Sea Level and Its Components (eds. Cazenave, A., Champollion, N., Paul, F. & Benveniste, J.) 191–219 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56490-6_9.

Li, D. et al. The impact of horizontal resolution on projected sea‐level rise along US east continental shelf with the community earth system model. J. Adv. Model Earth Syst. 14, e2021MS002868 (2022).

Lowe, J. A. & Gregory, J. M. Understanding projections of sea level rise in a Hadley Centre coupled climate model. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 111, C11014 (2006).

Gregory, J. M. et al. Concepts and terminology for sea level: mean, variability and change, both local and global. Surv. Geophys. 40, 1251–1289 (2019).

Wang, S. Data for “Fast recovery of North Atlantic sea level in response to atmospheric CO2 removal”, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25340890.v6 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (NRF2022R1A3B1077622), and supported by the Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT) [NO.RS-2021-II211343, Artificial Intelligence Graduate School Program (Seoul National University)]. Y.S. is also supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00334637). The CESM simulation and data transfer were supported by the National Supercomputing Center with supercomputing resources (KSC-2024-CHA−0001), and the National Center for Meteorological Supercomputer of the Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA) and the Korea Research Environment Open NETwork (KREONET), respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.-H.Oh. and J.-S.Kug conceived the idea of the project. S.Wang compiled the data, conducted analyses, prepared the figures, and drafted the article. J-H.Oh. and Y.Shin contributed analyses and editing. All authors discussed the results and revised the article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S., Shin, Y., Oh, JH. et al. Fast recovery of North Atlantic sea level in response to atmospheric carbon dioxide removal. Commun Earth Environ 5, 652 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01835-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01835-4