Abstract

Slow-slip events at global subduction zones relieve tectonic stress over days to years. Through slow-slip cycles, high fluid pressures observed at the top of subducting plates are thought to fluctuate, potentially due to the valving action of an impermeable layer near the plate interface. We model teleseismic scattering data at the Manawatu deep slow-slip patch at the Hikurangi margin in New Zealand and find high seismic P-to-S wave velocity ratios, VP/VS, in the upper ~5 km of the subducting Pacific Plate, reflecting sustained elevated fluid pressures that decrease during slow-slip and increase during inter-slow-slip periods. Within a ~ 3 km thick lower crustal layer of the overriding Australian Plate, decreasing VP/VS during inter-slow-slip periods reflects permeability reduction due to mineral precipitation. Increasing VP/VS during slow-slip reflects increasing permeability and crack density, facilitating upward fluid transfer through this layer. Our results suggest it acts as a valve to relieve high fluid pressures in the subducting slab.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Slow-slip events occur from shallow (10–15 km) to deep (30–50 km) depths on the thrust fault at most subduction zones and release seismic energy equivalent to M > 6 earthquakes over days to months to years. A common feature in slow-slip regions resolved by seismic imaging is a seismic low-velocity layer proposed to indicate the presence of high fluid pressures, or overpressures, near the plate interface1,2,3 capped by an inferred impermeable layer. There is mounting evidence that fluid pressure flux from the overpressured slab to the overlying crust occurs during slow-slip events. The inferences from these studies relate seismic velocity changes4,5,6, attenuation7 or stress changes8 to fluid pressure fluctuations in the bulk of the subducting oceanic crust and the overriding crust, which support a fault-valve hypothesis where the impermeable layer gets breached during slow-slip events, allowing upward fluid (and fluid pressure) redistribution. Resealing of the layer during inter-slow-slip periods helps rebuild overpressure in the slab. Structural and petrological investigations of exhumed subduction thrust material suggest various mechanisms to explain the permeability changes in this layer, including mineral precipitation9,10,11,12, cataclasis13 and metasomatism14. However, it is important to resolve temporal changes in physical properties in situ in the layers above and below plate interface in slow-slip regions to understand how such an inferred impermeable layer behaves during slow-slip cycles.

P-receiver functions computed from teleseismic earthquakes are sensitive to the seismic scattering structure beneath a seismograph and represent the amplitude and delay times of P-to-S wave conversions and their multiples at velocity discontinuities. Amplitudes of receiver functions are sensitive to the S-wave velocity (VS) contrast across layers. In contrast, delay times of converted phases in receiver functions are sensitive to the P-to-S wave velocity ratio (VP/VS) and thickness of layers. Receiver functions have been predominantly focused on estimating static subsurface VP/VS models, which provide evidence for elevated VP/VS ( > 2.0) in slow-slip regions in multiple subduction zones1,2,15,16. Because teleseismic waves sample the same crustal volume beneath the seismograph with a quasi-regular temporal resolution provided by the annual global average of about 1500 M > 5 earthquakes, receiver functions have been used to study time-varying seismic velocity structures caused by various tectonic6,17,18 and hydrologic perturbations19. However, due to epicentral distance constraints imposed in receiver function computations, only a subset of the ~1500 annual M > 5 earthquakes can be used at a single seismograph.

Beneath Vancouver Island in the Cascadia subduction zone, receiver functions resolve a change in the estimated VS contrast of ~0.05–0.10 km s−1 across the low-velocity layer after slow-slip events6. These statistical inferences represent a bulk change in VS contrast relative to the slow-slip onset times but cannot resolve the temporal evolution of these changes above and below the plate interface. This is because slow-slip events in Cascadia are relatively short (~10–14 days) and frequent (~14 months), necessitating receiver function stacking over several events. Capturing the temporal variations in seismic velocities above and below the plate interface in slow-slip regions remains a critical focus for understanding fluid migration during slow-slip cycles.

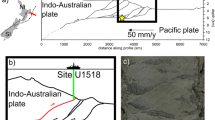

In this study, we infer temporal changes in seismic P-to-S wave velocity ratio (VP/VS) above and below the plate interface of the Hikurangi subduction margin near Manawatu in New Zealand, where the Pacific Plate subducts beneath the Australian Plate (Fig. 1a). Here, deep slow-slip events occur at depths of ~20–50 km (Fig. 1b) on the subduction thrust every ~5 years and last for ~1-2 years20,21. They are, therefore, a perfect candidate for studying temporal changes in VP/VS due to their longer periodicity and the availability of long-term continuous seismic waveform data from the early 2000s from GeoNet, the New Zealand National Seismograph Network22. We resolve temporal changes in VP/VS in the layers above and below the plate interface that correlate with geodetic displacements across slow-slip cycles. Our work further illuminates the velocity structure at the plate interface and how it changes during slow-slip, with implications for global slow-slip events.

a Tectonic setting around New Zealand. b Lower North Island of New Zealand where deep slow-slip events (SSEs) occur. Coloured triangles are permanent seismographs of GeoNet (green - broadband, purple - short-period). Seismographs used in this study are TSZ, MRZ, WAZ, PNHZ, KRHZ and WPHZ (labelled). Blue contours indicate the cumulative slip on the plate interface during multiple slow-slip events between 2002 and 201420. Black dashed contours indicate the depth of the plate interface52. Red circles denote tremor and low-frequency earthquake locations46,47.

Results and discussion

Overpressured subducting slab at the deep slow-slip zone

We determine a horizontally layered, one-dimensional VP/VS model of the subsurface beneath the TSZ broadband seismograph station that sits above the Manawatu deep slow-slip patch (Fig. 1b) by inverting a linear stack of radial receiver functions (see Methods). This one-dimensional velocity model depicts the presence of a ~ 2 km thick low VS, high VP/VS overburden layer near the surface, followed by a ~ 18 km thick section with relatively higher VS and lower VP/VS, interpreted as the overriding crust of the Australian Plate (Supplementary Fig. 1). This overriding crustal layer is underlain by a ~ 10 km thick section with low VS and high VP/VS, interpreted as a low-velocity layer. Beneath it, we resolve a ~ 12 km thick oceanic crust underlain by an oceanic mantle.

In a subduction zone setting, the assumption of horizontal layering is invalid, and seismic anisotropy is typically observed23,24. In such cases, transverse receiver functions will also show energy for teleseismic P-waves (Supplementary Fig. 2) arriving from back azimuths oblique to the dip direction of the subducting plate and/or the plunge direction of the anisotropic fabric23,24,25. These shortcomings in the horizontally-layered one-dimensional velocity inversion can lead to misestimated VP/VS. Nevertheless, the horizontally layered, one-dimensional velocity model provides a guide to simplifying a structural model that incorporates dipping layers in inverting the full set of radial and transverse receiver functions. When we incorporate dipping layers into the one-dimensional velocity model (see Methods), we obtain an average VP/VS model that reveals the presence of a 4.8 [−0.9/ + 2.0] km thick dipping layer with a VP/VS of 2.69 [−0.31/ + 0.28] (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3), that we interpret as a low-velocity layer composed of underplated sediments and the fractured upper oceanic crust of the subducting Pacific Plate. A 4.8 km thick low-velocity layer is consistent with the combined thickness of the subducting sediments and the fractured upper oceanic crust revealed from active-source seismic reflection and refraction data from the southern Hikurangi margin26,27,28. Tomographic images of this region show a more moderate VP/VS of about 1.8 and QS/QP (seismic S-wave to P-wave quality factor ratio) ranging from about 0.8 to 1.329. Compared to receiver functions that are more sensitive to sharp changes in velocity (e.g. plate interface), tomography smoothes variations in velocities due to path averaging and smearing effects that may result in mis-estimation of seismic velocities30,31. Nevertheless, these moderate VP/VS and QS/QP values in tomographic models are interpreted to indicate high fluid pressure (low effective pressure) and/or high fluid saturation32.

Receiver function imaging studies report VP/VS ranging between 2.0 and 3.0 for the low-velocity layers interpreted for Cascadia, Costa Rica, Japan and Mexico subduction zones at similar depths where slow-slip (also known as episodic tremor and slip) is observed1,2,15,16. These high VP/VS are proposed to result from high fluid pressures sustained in a porous subducting slab capped by a low-permeability barrier1. Laboratory measurements of ultrasonic (i.e. 1 MHz) seismic velocities in foliated metasedimentary rocks reveal that VP/VS > 2 can also be reached for seismic waves travelling perpendicular to the foliation under fluid-saturated conditions in phyllosilicate-rich metapelitic rocks with aligned, small aspect ratio pores under near lithostatic pore pressures33,34,35. Similar high VP/VS can also be reached in intensely micro-fractured isotropic rocks under high fluid pressure conditions at subsonic frequencies (about 1 Hz)36. Regardless of the composition of the material or measurement mechanism, it is clear that high fluid pressures (i.e. low effective stresses) yield high measured VP/VS values.

Temporal changes in receiver function power spectral density, total power and VP/VS at the deep slow-slip zone

Receiver functions can be used to resolve temporal changes in the crustal seismic velocity structure because they repeatedly (although irregularly; Supplementary Fig. 4) sample the subsurface at a seismograph from below. As receiver function amplitudes are sensitive to the velocity contrast across interfaces, we first investigate temporal changes in amplitude using the power spectral density of receiver functions along the radial and transverse directions. Power spectral density represents the power (squared amplitude) distribution in a waveform across a range of periods (or frequencies). Therefore, any observed temporal changes in receiver function power spectral density reflect changes in the seismic scattering structure to first order. Localising the depth of these changes from the power spectral density computed from a wide receiver function time window is challenging. We partially circumvent this by using a time window in the receiver functions when the P-to-S converted phases are expected at a particular interface (e.g. plate interface).

Time-lapse analysis of the receiver function power spectral densities at the TSZ broadband seismograph station, located above the Manawatu deep slow-slip patch (Fig. 1b), shows systematic changes in the power spectral density at periods between 0.3 and 0.8 s (~1 and 3 Hz) (Fig. 3a, b). The power spectral density and the total power computed by integrating the power spectral density between these periods correlate with the eastward geodetic displacement at the collocated TAKP global navigation satellite system (GNSS) station37, which is proportional to the amount of slip on the subduction thrust, through three slow-slip cycles between 2003 and 2023 (Fig. 3a, b). The correlation is most evident during the slow-slip period starting in 2014. During inter-slow-slip periods, when the geodetic displacement decreases, power spectral density and total power decrease. In contrast, during slow-slip periods, these trends reverse. As the receiver function power spectral densities have been computed within a time window where the direct P-to-S converted phases at the plate interface are expected (see Methods), they may represent temporal changes in VP/VS of the layers near the plate interface. Similar observations are made at the short-period seismographs WPHZ and PNHZ above the high slip region of the slow-slip patch (Fig. 1b) for a shorter time period than TSZ (Supplementary Figs. 5, 6). Receiver function power spectral density and total power at MRZ, WAZ (broadband) and KRHZ (short-period) seismographs that are near or outside of the boundary of the slow-slip patch (Fig. 1b) do not display a correlation with the geodetic displacements at collocated GNSS stations (Supplementary Figs. 7–9).

Observed receiver function PSDs along (a) radial and (b) transverse directions. Panels below (a) and (b) show normalised eastward geodetic displacement at the co-located TAKP global navigation satellite system receiver station and the observed total power between 0.3 and 0.8 s periods. Predicted receiver function PSDs along (c) radial and (d) transverse directions for the best-fit model. Panels below (c) and (d) show VP/VS variation in the low-velocity layer and the ~3.4 km thick lower crustal layer above it, and the predicted total power between 0.3 and 0.8 s periods.

To investigate the transient behaviour encompassing the plate interface, we invert the observed changes in total power from radial and transverse receiver function power spectral density at TSZ seismograph (Fig. 3a, b; see Methods). Model parameters include VP/VS in the low-velocity layer in the subducting plate and the thickness and VP/VS of a lower crustal layer in the overriding plate (Supplementary Fig. 10). We force these to vary similarly to the geodetic displacement time series, either positively or negatively (see Methods for further details). Our results indicate that the VP/VS in the low-velocity layer varies between ~2.6 and ~2.8 with an opposite polarity to the geodetic displacement (Fig. 3c, d). The sign of the correlation suggests that VP/VS increases during inter-slow-slip periods and decreases during slow-slip periods. VP/VS in an estimated 3.4 [−1.9/ + 0.7] km thick layer at the base of the lower crust of the overriding plate and above the low-velocity layer of the subducting plate varies between ~1.6 and ~1.8 (Fig. 3c,d; Supplementary Fig. 10). This variation has an opposite polarity to the low-velocity layer beneath it, with VP/VS decreasing during inter-slow-slip periods and increasing during slow-slip periods.

The optimal temporal changes in VP/VS in the low-velocity layer and the ~3.4 km thick, lower crustal layer above it are within the uncertainties in the static velocity model (Fig. 1). We test if the optimal temporal changes in VP/VS are statistically significant by bootstrapping 1000 times the VS in these two layers, computing synthetic receiver functions along radial and transverse directions and estimating the correlation coefficient between eastward geodetic displacement and total power time series (Supplementary Fig. 11). The correlation coefficient between geodetic displacement and total power with the optimum temporal variations in the two layers falls outside the 95% confidence intervals of the correlation coefficients from the bootstrap sampling. This suggests that the estimated optimum temporal variations in VP/VS of the two layers are statistically significant.

Implications for fault-valving during slow-slip

The small temporal changes (±0.1) in the high VP/VS values observed in the low-velocity layer suggest that high fluid pressures fluctuate slightly but are mostly maintained during slow-slip cycles (Fig. 3c, d). This change represents a fluid pressure drop of <20 MPa based on experimental VP and VS for representative rocks33,35,38. It is consistent with fluid pressure drops during slow-slip events in Cascadia6 and the northern Hikurangi8 that argue for a fault-valve action during slow-slip cycles4,5,6,8. Similarly, VP/VS in the ~3.4 km thick layer in the lower crust and above the low-velocity layer varies between ~1.6 and ~1.8 (Fig. 3c, d). The lowest VP/VS of ~1.6 reached towards the end of inter-slow-slip periods requires special attention because, in dry, isotropic rocks, VP/VS typically varies between ~1.65 and 1.839,40. VP/VS values as low as ~1.6 in the lower crust of subduction zone forearcs9,15 have been interpreted to indicate bulk silica enrichment through sustained quartz precipitation. In addition, low VP/VS can result from material anisotropy rather than an unusual composition41. Experimental and numerical results suggest that foliation- or crack-induced anisotropy in dry, quartz-rich rocks can yield VP/VS ranging from ~1.5 to 1.7 for both vertically polarised shear waves (SV) and horizontally polarised shear waves (SH) propagating at directions 0°−20° from the normal to the crack fabric for crack densities ranging from 0.1 to 0.534. For fluid-saturated anisotropic rocks at low effective pressure, VP/VS increases with increasing crack density and decreasing crack aspect ratio, with porosity imparting only a second-order control on VP/VS33.

In one end-member scenario, a VP/VS increase from ~1.6 to ~1.8 during slow-slip periods occurring within a thin layer kept at constant fluid saturation can arise from a ~ 10-20° change in the angle between wave propagation and crack fabric. However, teleseismic P-waves propagate almost vertically and sample the subducting material orthogonal (i.e., within 20°) to the slab-parallel shear-zone fabric. Furthermore, we surmise that the bulk orientation of the cracks or foliation planes does not change by more than 5°−10° during slow-slip cycles based on evidence from studies that infer temporal variations in the principal (sub-vertical) stress axis (σ3) (ref. 8) during slow-slip events. In a more plausible scenario, a similar VP/VS increase may arise from a combination of progressive fluid saturation in dry anisotropic rocks, an increase in crack density34,36 or a decrease in crack aspect ratio33,34. A commensurate VP/VS decrease is associated with fluid de-saturation and a decrease in crack density due to fault healing.

Conclusions

Our results provide observational evidence of fault-valving action during slow-slip. In the low-velocity layer, fluid pressure decreases during slow-slip and recovers between successive events, indicating fluctuations that can either drive or are a consequence of slow-slip. In the ~3.4 km thick layer in the lower crust above the low-velocity layer, the interpreted physical changes that can explain the temporal changes in VP/VS imply that (1) during inter-slow-slip periods, it acts as an impermeable layer (low crack density) that traps the fluids in the overpressured low-velocity layer; (2) during slow-slip periods, the permeability of this layer increases due to fault rupture, which increases crack density and fluid mobilisation from the low-velocity to the thin layer, reducing fluid overpressure in the subducting slab (Fig. 4).

Furthermore, the inter-slow-slip decrease in VP/VS to the low values associated with silicate-rich rocks is compatible with mineral precipitation-induced resealing and crack density reduction. Evidence of giant quartz vein systems in various tectonic settings10,11,12,42 suggests silica precipitation from transient permeability changes at brittle-ductile conditions10 following a fault-valve model. The pressure and temperature conditions for massive silica deposition at the base of the lower crust10,11,15,42,43 are present in the deep slow-slip region at the southern Hikurangi margin44,45. The magnitude of the changes in crack density and permeability is difficult to quantify based on VP/VS variations alone; however, our results suggest that they occur within a thin layer in the lower crust above the low-velocity layer without the need for major fluid redistribution within the overriding crust. This might explain the absence of tremor activity at the Manawatu slow-slip region in the Hikurangi margin, unlike the Kaimanawa slow-slip region immediately to the northeast46,47 (Fig. 1b). This layer may behave as the low-permeability seal in the fault-valve hypothesis that breaches during slow-slip6,8,48 (Fig. 4).

Methods

Receiver function computation

We compute receiver functions by taking the spectral ratio between vertical and horizontal (radial and transverse) components of ground motion using the RfPy Python package49. We use all M > 5 earthquakes that occurred between the start date of each seismograph until June 2022 and within epicentral distances between 30° and 90°. As a quality control metric, we calculate the vertical-component signal-to-noise ratio for each earthquake within 30-second windows before (noise) and after (signal) the predicted P-wave arrival time. We perform minimal pre-processing (demean, detrend and taper) and employ a modified Wiener filtering approach18 to regularise the spectral ratio and reduce the effects of seasonal noise that cause ground tilting and leakage of the vertical into horizontal components. We identify and remove outliers in receiver functions based on the robust standard units of the time series variance calculated over the first 30 seconds. Radial and transverse receiver functions with a signal-to-noise ratio > 5 dB calculated at TSZ seismograph and bandpass filtered between 0.1 and 2 Hz are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2 for visualisation.

Modelling the seismic velocity structure

We employ a two-step process to estimate a seismic velocity profile beneath the TSZ seismograph. In the first step, we invert the stack of all radial receiver functions with a signal-to-noise ratio >10 dB and bandpass filtered between 0.1 and 2.0 Hz to estimate a horizontally layered isotropic VP/VS model discretised at 2 km depth intervals from the surface down to a depth of 60 km (Supplementary Fig. 1). The background VP model consists of gradually increasing values from 6 to 8 km s−1 between 15 and 50 km depth. In the inversion, we set the starting VP/VS model to 1.78 for all layers and estimate VP/VS as a function of depth (i.e., 30 parameters to estimate). The corresponding VS model is obtained by scaling the background VP using the estimated VP/VS model. We use a χ2 misfit calculated over the first 25 s of receiver function lag times in a Sequential Least Squares Programming algorithm implemented in the SciPy50 Python library. Synthetic receiver functions are calculated using a matrix-propagator method implemented in the Telewavesim51 Python package. This software cannot model layer dip but is computationally efficient for a multi-layered inversion of the subsurface VP/VS structure. Due to the sensitivity of this approach to the background VP and the initial VP/VS models, cycle skipping and local minima, we perform the inversion 100 times with randomly perturbed background VP models, each time setting the initial VP/VS to 1.78 in all layers, and re-estimate a VP/VS model. For each inversion, VP perturbations within each layer are drawn from a normal distribution with a standard deviation of 0.2 km s−1. We take the mean of the ensemble VP/VS and VS profiles as our final model (Supplementary Fig. 1). The resulting velocity model depicts the presence of a ~ 2 km thick low VS, high VP/VS overburden layer near the surface, followed by a ~ 18 km thick section with relatively higher VS and lower VP/VS, interpreted as the overriding crust of the Australian Plate. This overriding crustal layer is underlain by a ~ 10 km thick section with low VS and high VP/VS, interpreted as a low-velocity layer. Beneath it, we resolve a ~ 12 km thick oceanic crust underlain by an oceanic mantle.

We use this mean ensemble model to guide the generation of a simplified model with fewer layers (and, therefore, model parameters) and re-estimate an isotropic VP/VS (or VS) model that includes dipping layers. We discretise the model into six major units: overburden, upper crust, lower crust, a low-velocity layer that comprises underplated sediments and the fractured upper oceanic crust, lower oceanic crust, and a half-space upper mantle. We consider the low-velocity layer and oceanic crust as coherently dipping units and fix their strike and dip to 215° and 20°, respectively, based on the plate interface model for the Hikurangi subduction margin52. In all crustal units, including the overburden and the low-velocity layer, VP is fixed at 6.0 kms−1; in the upper mantle halfspace, VP and VP/VS are fixed at 8.1 kms−1 and 1.81, respectively. We search for the VP/VS and thickness within all crustal layers using bounds on parameters derived from the one-dimensional, horizontally layered seismic velocity model (Supplementary Table 1). We use the PyRaysum53 Python package to compute synthetic receiver functions because it can handle layer dip. The misfit function used for the optimisation is (1-CC), where CC is the sum of the cross-correlation coefficients between the observed and computed receiver functions along both radial and transverse components for all slowness and backazimuth values. We perform a global optimisation using the Optuna54 Python package with 10,000 iterations to solve for the average thickness and VP/VS of the overburden, upper crust, lower crust, low-velocity layer and lower oceanic crust (10 parameters to estimate). Parameter uncertainties are estimated by computing the misfit at the 95% confidence interval using a χ2 statistic as defined in Eq. 1. Here df = # iterations - # parameters = (10,000–10) = 9,990.

The overburden, upper and lower crustal layers have thicknesses of 1.9 [−0.2/ + 0.4], 10.8 [−2.7/ + 2.8] and 11.3 [−2.5/ + 2.0] km and VP/VS ratios of 2.35 [−0.30/ + 0.24], 1.61 [−0.01/ + 0.07] and 1.67 [−0.07/ + 0.1], respectively. The low-velocity layer and the lower oceanic crustal layer have thicknesses of 4.8 [−0.9/ + 2.0] and 7.8 [−2.2/ + 1.4] km and VP/VS ratios of 2.69 [−0.31/ + 0.28] and 1.72 [−0.12/ + 0.13], respectively (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3).

Computing receiver function power spectral density and total power

Power spectral density of raw receiver functions along radial and transverse directions with signal-to-noise ratio > 2 dB are computed within a time window around the lag times when the P-to-S converted phases from the plate interface are expected. For the TSZ seismograph (Fig. 1b), based on the plate interface model for the Hikurangi subduction zone52, this time window corresponds to lag times between 3 and 8 seconds for the direct P-to-S converted phase. Power spectral density is computed using the multi-taper method55 and resampled in full-octave period averages taken at 1/8 octave intervals to reduce the variance of the estimates18,56. The total power time series is computed by integrating the power spectral density within the frequency range of observed temporal changes. For TSZ seismograph, the period range is between 0.3 and 0.8 s (frequencies from ~1 to 3 Hz) (Fig. 3).

To improve temporal coherency, we stack the computed receiver function power spectral density in overlapping time bins. However, the distribution of the backazimuth and the slowness of receiver functions in each bin can affect the stacked power spectral density. To examine this, we consider bin sizes of 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 42 and 48 months, and overlaps from 5% to 95% in increments of 5% and determine a distance between event distribution within the bins and that of the entire dataset. The null hypothesis is that the distributions are the same. We transform the event distribution to a lower hemispheric projection using backazimuth and incidence angles (declination and 90°-inclination for an upcoming teleseismic P-ray). For a given bin size and overlap, we calculate the mean optimal transport distance based on the Earth mover’s distance problem57 for multi-dimensional distributions with unequal size between the event distribution within each bin and that of the entire dataset. The result is a time series of optimal transport distances for a given combination of window size and overlap (Supplementary Figs. 12a, 13a). However, the meaning of the mean optimal transport distance value from this analysis is unclear. To mitigate this, we perform a bootstrap analysis of this process by 1) shuffling the overall event distribution, 2) repeating the optimal transport distance analysis on the shuffled distribution using the same bin size and overlap, and 3) calculating the mean and 95% confidence intervals on the bootstrap distribution (1000 bootstrap samples). We then compare the observed optimal transport distances and the distribution of bootstrapped optimal transport analysis for each bin size and overlap. We also show the correlation coefficient between the observed total power time series along radial and transverse directions and the eastwards geodetic displacement as a function of bin size and overlap (Supplementary Figs. 12b, c, 13b).

Overall, the observed mean optimal transport distances decrease with increasing bin size, which is expected because more and more of the entire event distribution is included within each bin (i.e. they become more similar to the entire dataset, and the optimal transport distances decrease). For the TSZ station, up to ~15–18 months, the mean optimal transport distance is within the 95% confidence interval (Supplementary Figs. 12a, 13a), which means the observed event distribution (within each window) is a randomised version of the overall event distribution (i.e., the null hypothesis cannot be rejected). Where they fall outside of the confidence interval, they are statistically different (i.e., the event distribution within the bins is statistically different than that of the entire dataset), at which point we cannot exclude that observed power spectral density correlations with geodetic displacement are due to the event distribution. The break occurs at ~15–18 months. We note that this break would occur at different bin sizes for different confidence levels. Furthermore, a bin size >= 18 months and overlap >= 75% is required to obtain a correlation coefficient >0.7 (Supplementary Figs. 12b, c, 13b). Based on these observations, we find a bin size of 18 months with a 95% overlap optimal that supports a significant correlation between receiver function power and geodetic displacement time series. We surmise that shorter bins do not see a high correlation because the event distribution skews the results. We also note that the 18-month window corresponds to one-quarter of the recurrence time of deep slow-slip events here, allowing us to see changes at a sufficient temporal resolution.

Modelling temporal changes in receiver function power spectral density and total power

To model the temporal variations in observed receiver function power spectral density and total power, we start with the simplified seismic velocity model at TSZ seismograph with five crustal layers accounting for the dip in the low-velocity layer and the lower oceanic crust (Fig. 2) as the reference, unperturbed model. To keep the problem tractable, we examine temporal variations in VS within two layers bounding the plate interface: the low-velocity layer and an additional, overriding and dipping layer characterised by the seismic velocity of the lower crust but of unknown thickness. This layer (and its time-varying properties) is required to reproduce power spectral density variations that scale with the observed power spectral density; models that instead distribute the time-varying properties over the entire overriding crust do not produce a good match to the observed receiver functions and their power spectral densities. The time-varying VS perturbations in these two layers are computed as scaled versions of the normalised eastward geodetic displacement at TSZ seismograph (TAKP GNSS station), superimposed on the background seismic velocities, which is justified by the high correlation between the geodetic data and the total power time series. The VS time series are thus forced to follow the same temporal pattern as the geodetic displacement time series while their amplitude is constrained by the receiver function power spectral density and total power time series. We thus estimate three model parameters: the two VS scaling factors and the thickness of the overriding lower crustal layer.

Synthetic receiver functions are computed using backazimuth and slowness values extracted for all observed receiver functions with signal-to-noise ratio > 2 dB. We calculate synthetic power spectral density and total power from these receiver functions following the same procedure as above. We use a misfit defined as the sum of two terms: the anti-correlation misfit (1- CC) between observed and predicted total power time series and the average of the temporal deviation of predicted lag times of each phase (as we do not observe large temporal variation in phase lag-times in the observed receiver functions; Supplementary Fig. 4). We perform a global optimisation using the Optuna Python package54 with 1000 iterations to estimate the three model parameters (Supplementary Fig. 10). We also estimate the 95% confidence intervals of the optimal parameters using a χ2 test (Eq. 1; Supplementary Fig. 10). The optimum VS scaling factor and the thickness of the layer at the base of the lower crust are −0.06 ± 0.02 and 3.4 [−1.9/ + 0.7] km, respectively. The optimum VS scaling factor for the low-velocity layer is 0.04 ± 0.01. The VS time series for the two layers are obtained by applying the scaling factor to the normalised geodetic displacement time series. These VS time series are converted to VP/VS using the constant VP of 6.0 kms−1 (Fig. 3c, d). Time-sorted predicted receiver functions using these optimum parameters are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4e, f.

Data availability

Seismic and geodetic data used in the study are openly available from the New Zealand National Seismograph Network, GeoNet (https://doi.org/10.21420/G19Y-9D40; https://doi.org/10.21420/30F4-1A55?x=y). Source data used for generating Fig. 3 are available from the public repository at https://github.com/pasansherath/RF_Timelapse_PSD/tree/master/commsenv_figs.

Code availability

The receiver function time-lapse power spectral density computation code can be accessed from the public repository at https://github.com/pasansherath/RF_Timelapse_PSD.

References

Peacock, S. M., Christensen, N. I., Bostock, M. G. & Audet, P. High pore pressures and porosity at 35 km depth in the Cascadia subduction zone. Geology 39, 471–474 (2011).

Audet, P., Bostock, M. G., Christensen, N. I. & Peacock, S. M. Seismic evidence for overpressured subducted oceanic crust and megathrust fault sealing. Nature 457, 76–78 (2009).

Gase, A. C. et al. Subducting volcaniclastic-rich upper crust supplies fluids for shallow megathrust and slow slip. Sci Adv 9, eadh0150 (2023).

Wang, W. et al. Temporal velocity variations in the northern Hikurangi margin and the relation to slow slip. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 584, 117443 (2022).

Zal, H. J. et al. Temporal and spatial variations in seismic anisotropy and VP/VS ratios in a region of slow slip. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 532, 115970 (2020).

Gosselin, J. M. et al. Seismic evidence for megathrust fault-valve behavior during episodic tremor and slip. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay5174 (2020).

Ito, Y. & Nakajima, J. Temporal variations in and above a megathrust following episodic slow‐slip events. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL103577 (2023).

Warren-Smith, E. et al. Episodic stress and fluid pressure cycling in subducting oceanic crust during slow slip. Nat. Geosci. 12, 475–481 (2019).

Hyndman, R. D., McCrory, P. A., Wech, A., Kao, H. & Ague, J. Cascadia subducting plate fluids channelled to fore-arc mantle corner: ETS and silica deposition. J. Geophys. Res. [Solid Earth] 120, 4344–4358 (2015).

Tannock, L. et al. Microstructural analyses of a giant quartz reef in south China reveal episodic brittle-ductile fluid transfer. J. Struct. Geol. 130, 103911 (2020).

Breeding, C. M. & Ague, J. J. Slab-derived fluids and quartz-vein formation in an accretionary prism, Otago Schist, New Zealand. Geology 30, 499–502 (2002).

Saishu, H., Okamoto, A. & Otsubo, M. Silica precipitation potentially controls earthquake recurrence in seismogenic zones. Sci. Rep. 7, 13337 (2017).

Angiboust, S. et al. Probing the transition between seismically coupled and decoupled segments along an ancient subduction interface. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 16, 1905–1922 (2015).

Lindquist, P. C., Condit, C. B., Hoover, W. F., Hernández-Uribe, D. & Guevara, V. E. Metasomatism and slow slip: Talc production along the flat subduction plate interface beneath Mexico (Guerrero). Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 24, e2023GC010981 (2023).

Audet, P. & Bürgmann, R. Possible control of subduction zone slow-earthquake periodicity by silica enrichment. Nature 510, 389–392 (2014).

Audet, P. & Schwartz, S. Y. Hydrologic control of forearc strength and seismicity in the Costa Rican subduction zone. Nat. Geosci. 6, 852–855 (2013).

Porritt, R. W. & Yoshioka, S. Evidence of dynamic crustal deformation in Tohoku, Japan, from time-varying receiver functions. Tectonics 36, 1934–1946 (2017).

Audet, P. Temporal variations in crustal scattering structure near Parkfield, California, using receiver functions. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 100, 1356–1362 (2010).

Kim, D. & Lekic, V. Groundwater Variations From Autocorrelation and Receiver Functions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 13722–13729 (2019).

Wallace, L. M. Slow Slip Events in New Zealand. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 48, 175–203 (2020).

Ikari, M. J. et al. Observations of laboratory and natural slow slip events: Hikurangi subduction zone, New Zealand. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 21, e2019GC008717 (2020).

GNS Science. GeoNet Aotearoa New Zealand Seismic Digital Waveform Dataset [Data set]. https://doi.org/10.21420/G19Y-9D40 (2021).

Savage, M. K. Lower crustal anisotropy or dipping boundaries? Effects on receiver functions and a case study in New Zealand. J. Geophys. Res. [Solid Earth] 103, 15069–15087 (1998).

Kyryliuk, T. T., Audet, P., Gosselin, J. M. & Schaeffer, A. J. Crustal seismic anisotropy along the continental margin in western Canada from receiver function analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 127, e2022JB024748 (2022).

Audet, P. Layered crustal anisotropy around the San Andreas Fault near Parkfield, California. J. Geophys. Res. [Solid Earth] 120, 3527–3543 (2015).

Tozer, B., Stern, T., Lamb, S. L. & Henrys, S. A. Crust and upper-mantle structure of Wanganui Basin and southern Hikurangi margin, North Island, New Zealand as revealed by active source seismic data. Geophys. J. Int. 211, 718–740 (2017).

Herath, P. et al. Hydration of the crust and upper mantle of the Hikurangi Plateau as it subducts at the southern Hikurangi margin. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 541, 116271 (2020).

Mochizuki, K. et al. Plumes, Recycling of depleted continental mantle by subduction and Hikurangi Plateau Large Igneous Province, southwest Pacific. Geology 47, 795–798 (2019).

Eberhart-Phillips, D., Reyners, M., Bannister, S., Chadwick, M. & Ellis, S. Establishing a Versatile 3-D Seismic Velocity Model for New Zealand. Seismol. Res. Lett. 81, 992–1000 (2010).

Allam, A. A. et al. Ten kilometer vertical Moho offset and shallow velocity contrast along the Denali fault zone from double-difference tomography, receiver functions, and fault zone head waves. Tectonophysics 721, 56–69 (2017).

Kind, R. & Yuan, X. Seismic, Receiver Function Technique. in Encyclopedia of Solid Earth Geophysics (ed. Gupta, H. K.) 1258–1269 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2011).

Eberhart-Phillips, D., Bannister, S. & Reyners, M. Deciphering the 3-D distribution of fluid along the shallow Hikurangi subduction zone using P- and S-wave attenuation. Geophys. J. Int. 211, 1032–1045 (2017).

Fliedner, C. & French, M. E. Pore and mineral fabrics control the elastic wave velocities of metapelite with implications for subduction zone tomography. J. Geophys. Res. [Solid Earth] 126, e2021JB022361 (2021).

Wang, X. Q. et al. High Vp/Vs ratio: Saturated cracks or anisotropy effects? Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, 2–7 (2012).

Miller, P. K. et al. P‐ and S‐wave velocities of exhumed metasediments from the Alaskan subduction zone: Implications for the in situ conditions along the megathrust. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094511 (2021).

Pimienta, L. et al. Anomalous Vp/Vs ratios at seismic frequencies might evidence highly damaged rocks in subduction zones. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 12,210–12,217 (2018).

GNS Science. GeoNet Aotearoa New Zealand Continuous GNSS Network Time Series Dataset [Data set]. https://doi.org/10.21420/30F4-1A55 (2000).

Christensen, N. I. Pore pressure, seismic velocities, and crustal structure. in Geophysical framework of the continental United States: Geological Society of America Memoir 172 (ed. Pakiser, L. C., and Mooney, W. D.) 783–798 (1989).

Ji, S., Wang, Q. & Li, L. Seismic velocities, Poisson’s ratios and potential auxetic behavior of volcanic rocks. Tectonophysics 766, 270–282 (2019).

Wawrzyniak-Guz, K. Rock physics modelling for determination of effective elastic properties of the lower Paleozoic shale formation, North Poland. Acta Geophys 67, 1967–1989 (2019).

Hacker, B. R. & Abers, G. A. Subduction Factory 5: Unusually low Poisson’s ratios in subduction zones from elastic anisotropy of peridotite. J. Geophys. Res. [Solid Earth] https://doi.org/10.1029/2012JB009187.

Kerrich, R. & Feng, R. Archean geodynamics and the Abitibi-Pontiac collision: implications for advection of fluids at transpressive collisional boundaries and the origin of giant quartz vein systems. Earth-Sci. Rev. 32, 33–60 (1992).

Manning, C. E. The solubility of quartz in H2O in the lower crust and upper mantle. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58, 4831–4839 (1994).

Fagereng, A. & Ellis, S. On factors controlling the depth of interseismic coupling on the Hikurangi subduction interface, New Zealand. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 278, 120–130 (2009).

McCaffrey, R., Wallace, L. M. & Beavan, J. Slow slip and frictional transition at low temperature at the Hikurangi subduction zone. Nat. Geosci. 1, 316–320 (2008).

Romanet, P. & Ide, S. Ambient tectonic tremors in Manawatu, Cape Turnagain, Marlborough, and Puysegur, New Zealand. Earth Planets Space 71, 1–9 (2019).

Aden-Antoniów, F. et al. Low‐frequency earthquakes downdip of deep slow slip beneath the North Island of New Zealand. J. Geophys. Res. [Solid Earth] 129, e2023JB027971 (2024).

Sibson, R. H. Stress switching in subduction forearcs: Implications for overpressure containment and strength cycling on megathrusts. Tectonophysics 600, 142–152 (2013).

Audet, P. RfPy: Teleseismic Receiver Function Calculation and Postprocessing. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4302558 (2020).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Audet, P., Thomson, C., Bostock, M. & Eulenfeld, T. Telewavesim: Python software for teleseismic body wave modeling. J. Open Source Softw 4, 1818 (2019).

Williams, C. A. et al. Revised interface geometry for the Hikurangi subduction zone, New Zealand. Seismol. Res. Lett. 84, 1066–1073 (2013).

Bloch, W. & Audet, P. PyRaysum: Software for modeling ray-theoretical plane body-wave propagation in dipping anisotropic media. Seismica 2, https://doi.org/10.26443/seismica.v2i1.220 (2023).

Akiba, T., Sano, S., Yanase, T., Ohta, T. & Koyama, M. Optuna: A Next-generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. in Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining 2623–2631 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2019).

Prieto, G. A., Parker, R. L. & Vernon, F. L. III A Fortran 90 library for multitaper spectrum analysis. Comput. Geosci. 35, 1701–1710 (2009).

McNamara, D. E. & Buland, R. P. Ambiente noise levels in the continental United States. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 94, 1517–1527 (2004).

Bonneel, N., van de Panne, M., Paris, S. & Heidrich, W. Displacement interpolation using Lagrangian mass transport. in Proceedings of the 2011 SIGGRAPH Asia Conference 1–12 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2011).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the constructive feedback on the manuscript by Jonathan Delph and two anonymous reviewers. This work was supported by a Discovery Grant to PA from the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada (#RGPIN-2018-03752) and by the University Research Chair program from the University of Ottawa.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.H. conceived the study and carried out the receiver function analysis and modelling. P.A. provided codes for receiver function calculation, inversion for velocity structure and conducted statistical testing. Both PH and PA interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Luca Dal Zilio and Carolina Ortiz Guerrero. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Herath, P., Audet, P. Fluid upwelling across the Hikurangi subduction thrust during deep slow-slip earthquakes. Commun Earth Environ 5, 697 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01864-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01864-z