Abstract

Ecosystem restoration is widely recognized as a key strategy to address social-ecological challenges. National governments have pledged to restore millions of hectares of land. However, the ability to accomplish these pledges remains opaque, because restoration efforts are influenced by complex social-ecological factors. We provide a global analysis of national-level enabling and hindering conditions and their relation to restoration pledges undertaken by different nations. We developed an archetype characterization of within-country conditions using biophysical, socio-economic and governance indicators. Additionally, we investigated between-country conditions by examining flows of embodied land. Our analysis suggests that the countries with the most ambitious restoration pledges also tend to have the weakest enabling conditions (and vice versa). These results highlight the need to account for social, economic and governance factors alongside biophysical factors when considering where restoration ought to take place.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The restoration of degraded terrestrial ecosystems is increasingly recognized as a key strategy to address climate change, biodiversity decline, and associated ecological and social challenges1,2. Ecosystem restoration can be defined as the process of halting and reversing the degradation of ecosystems3. Social-ecological restoration aims to simultaneously improve social and ecological conditions towards well-being for current and future generations4. A myriad of global initiatives seek to advance land-based ecosystem restoration, including the Bonn Challenge, which aims to restore 350 million hectares of land by 20305, as well as more regional initiatives such as the Great Green Wall in the Sahel region6,7, or the African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative8. Ecosystem restoration is also one of 23 global targets defined by the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (https://www.cbd.int/gbf/targets/), and the United Nations has declared 2021–2030 the Decade on Ecosystem Restoration9.

In response to these initiatives, countries have made ambitious pledges to restore millions of hectares of land10,11. However, the drive to meet ambitious national-level targets often eclipses careful assessment of restoration opportunities, failing to fully account for social-ecological contexts, including challenges related to biophysical, governance, or equity issues, among others12,13. Globally, there has been a rush to generate maps depicting restoration opportunities14,15, arguably in response to calls to produce usable science to inform various policies16. Restoration opportunity studies tend to focus on biophysical factors alone, to the detriment of restoration in practice. For example, a focus only on ecological dimensions of restoration might, in some contexts, inadvertently pave the way for land dispossession where restoration targets give the state license to intervene in what were previously locally-managed areas17,18,19. In other instances, national governments may leverage restoration as a way of exercising power, not always for the benefit of their citizens, and possibly at the expense of political or demographic minorities20. Such issues have led to the call for the use of an “equality lens” in restoration projects, putting the participation, engagement and well-being of local people at the center4,21,22,23. Recent research has begun to incorporate socio-economic and socio-demographic variables to characterize global ecosystem restoration in a more holistic way4,22. Yet, broad assessments of socio-economic and governance aspects in global restoration work are still few and far between21,24, and social-ecological restoration studies are still in their infancy4,22,24,25. Studies that holistically consider the biophysical, socio-economic and governance conditions that enable or hinder ecological restoration are needed in order to more accurately represent the realities of implementing national-level restoration pledges.

In addition to the biophysical, socio-economic and governance conditions within a nation that shape the feasibility of meeting national restoration pledges, global telecouplings (largely through international trade relations, but also through international aid) add an extra layer of complexity as to where and how ecosystem restoration is likely to occur26,27. The concept of “ecologically unequal exchange” postulates the existence of unequal material flows fueled by ‘Global North’ countries, which govern the global economic system and have greater access to both natural resources as well as to the sink capacity (i.e., ability to absorb biophysical, financial and other shocks) of ‘Global South’ countries28,29. In relation to ecosystem restoration, nations that are heavily dependent on exporting of primary ecological goods (food, timber, fibers etc.) may find their restoration efforts undermined by the need to maintain economically important exports30,31. In contrast, nations that have outsourced such primary production via imports may have greater capacity to restore their own ecosystems. One method of quantifying ecologically unequal exchange is to construct models of embodied human appropriated net primary productivity (eHANPP), which is a proxy measure of the amount of land embodied in traded biomass flows (i.e., the amount of land required to sustain those trade flows)32. Such models indicate the extent to which national economies are dependent on the outsourcing of intensive land use (thereby reducing pressure on their own lands). eHANPP models have, for example, been employed to quantify the reliance of the ‘Global North’ on material transfers from distant areas to feed their populations and resource-intensive industries32,33. Moreover, global restoration efforts may be creating new forms of ecologically unequal exchange. Many restoration commitments in the ‘Global South’ have emerged from global initiatives driven by the ‘Global North’, including carbon offsetting32, thereby outsourcing needed conservation and restoration action to locations in the ‘Global South’, contributing to a further entrenchment of systemically unequal ecological exchange33. Employing eHANNP as a method of analysis could help quantify and qualify the nature of ecological exchange inherent to globally telecoupled restoration projects, and shed light on pathways for more meaningfully and equitably meeting ambitions restoration goals in our highly connected–but highly unequal–planet.

Our study therefore posed the following research question: What are national-level social-ecological conditions for terrestrial ecosystem restoration, and how do these conditions relate to national restoration pledges in the context of global flows of embodied land? Here, we examined how a combination of socio-economic, governance and biophysical conditions relates to restoration pledges made by countries around the world. We reasoned that some combinations of conditions – for example, situations with weak governance, high poverty and low primary productivity – may be at odds with especially ambitious restoration pledges. However, to date, such problems have not been made explicit in discourses on ecosystem restoration. To address this question, we conducted a global analysis using a broad suite of globally available biophysical, socio-economic, and governance indicators for terrestrial ecosystems. Using these indicators, we developed a set of archetypes of country level social-ecological conditions that might enable or hinder ecosystem restoration. Further, we contextualized social-ecological archetypes with national restoration pledges. We used eHANPP to approximate the embodied flows of biomass (and corresponding land) among nations and the global telecouplings between them (i.e., between-country conditions), and sought to assess whether the same countries that are exporting important levels of biomass to other nations are also those seeking to restore major amounts of land. This, in turn, could indicate that wealthy countries have outsourced both biomass production and their restoration pressure to economically less well-off countries. Our approach thus builds on recent calls for “connected conservation” – conservation that considers both local-level conditions as well as global telecouplings because both drive local conservation action34 – and extends these ideas into the restoration sphere. The resulting archetypes are both a window into existing ecological exchange dynamics as well as a tool to help drive national restoration projects towards more effective and equitable outcomes.

Results

Unraveling within-country conditions for ecosystem restoration

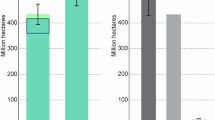

To understand the archetypical global patterns of within-country conditions that may influence nations’ restoration capacity, we clustered 207 countries according to their performance in 21 indicators across the biophysical, socio-economic and governance domains (Supplementary Table 2). In combination, these domains provide insights for within-country social-ecological conditions that may enable or hinder restoration efforts. Our analysis identified nine global archetypes showing contrasting social-ecological conditions. Some archetypes were spatially more clustered (e.g., archetype 9) whereas others were widely distributed across continents (e.g., archetype 2) (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table 1). These archetypes showed differentiated pledges in terms of the percentage of area [Kruskall–Wallis: χ²= 75.09; P < 0.0001] and the total area committed to restoration [Kruskall–Wallis: χ²= 90.616; P < 0.0001] (Fig. 1b, c).

Note that data on restoration pledges were not used to generate the archetypes, but to contextualize and compare them. a Spatial depiction of archetypes at the country level. Below the map are the boxplots summarizing restoration pledges of countries within each archetype as (b) the proportion of the countries’ area committed for restoration with the respective number of countries in square brackets; and (c) the total area. The mean and median values for each archetype are represented by a solid red line, and the black solid line, respectively. Countries are depicted according to an International Monetary Fund region (shape) and North-South (color) categorization. Y-axes of (b) and (c) are on a logarithmic scale.

Archetype 1 [Western Africa, Central America, Bangladesh - high pledges]

This archetype included 22 countries (Supplementary Table 2) located mainly in tropical regions of Africa (e.g., Togo) and Central America (e.g., El Salvador), and one Southeast Asian country (Bangladesh) (Fig. 1a). This archetype showed the highest share of agricultural lands, below-average technology levels, and above-average population growth, density and GDP growth. Typically, countries within this archetype were recipients of international aid and had below-average political stability, regulatory quality and tenure security values (Fig. 2). These countries committed the highest proportion of their territories for restoration (>25 %), in some cases above 80 % (Fig. 1b). However, countries in this archetype pledged relatively low total areas of land for restoration in absolute terms (i.e. many countries are small) (Fig. 1c).

Each panel represents one of the following archetypes: 1) Western Africa, Central America, Bangladesh - high pledges, 2) All geographies, high pledges, 3) Africa and Asia, high pledges, 4) Small African and Asian states, moderate pledges, 5) North Africa and Middle East, moderate pledges, 6) Eastern Europe and Caribbean, moderate pledges, 7) Canada, Scandinavia, Australia/New Zealand, modest pledges, 8) Small European and Caribbean states, modest pledges, 9) Western Europe, South Korea, Japan, very low pledges. The barplots show the deviation (z-score normalized values) of biophysical (blue bars), socio-economic (purple) and governance (brown) indicators characterizing each archetype from the global average (of all analyzed countries, represented by zero). The blue vertical lines delimit the range between −0.5 and 0.5, within which indicator values can be considered as close to the global average. The archetypes are organized in a decreasing order relative to the mean percentage of countries’ area committed for restoration (Fig. 1b). The mean area and standard deviation (sd) pledged per archetype are indicated next to each archetype’s name in square brackets. Black error bars represent the standard deviations of individual variables. Note that data on restoration pledges were not used to generate the archetypes, but to contextualize and compare them.

Archetype 2 [All geographies, high pledges]

This archetype included 44 countries (Supplementary Table 2), making it the largest and most widely distributed cluster. It included much of North, South and Central America (tropical and temperate), central-south-western Africa, Russia, as well as east and southeast Asian countries such as China, India, Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam (Fig. 1a). Countries in this archetype had the highest net primary productivity (NPP), and above-average values of human appropriation of net primary productivity (HANPP), protected areas, and forest share. These countries were mostly recipients of international aid (although a few countries were donors such as the United States of America), with below-average population density, as well as the highest percentage of indigenous population among all archetypes (Fig. 2). Countries in this archetype had the second highest proportion of their territories committed to restoration, as well as the highest total area (Fig. 1b, c).

Archetype 3 [Africa and Asia, high pledges]

This archetype included 24 countries (Supplementary Table 2) located in central Asia, (e.g., Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Mongolia), eastern Africa, (e.g., Tanzania and Mozambique), eastern Europe (e.g., Ukraine and Romania), South America (e.g., Venezuela and Uruguay), and the Mediterranean basin (e.g., Turkey and Tunisia) (Fig. 1a). This archetype exhibited a higher share of agricultural lands and strictly protected areas (IUCN I-III). These countries had below-average education, income and life expectancy, above-average population growth, and many were recipients of international aid. Regarding governance conditions, these countries had lower than average voice, political stability and regulatory quality (Fig. 2). Countries in this archetype had the third highest proportions of their territories committed to restoration, as well as the second highest total area (Fig. 1b, c).

Archetype 4 [Small African and Asian states, moderate pledges]

This archetype incorporated 34 countries (Supplementary Table 2) located mainly on the Arabian Peninsula, and in western tropical Africa (Fig. 1a). Countries in this archetype had below-average NPP, share of protected areas, agricultural lands, and non-productive areas. In the socio-economic domain, they were characterized by above-average technology and population density. These countries were also generally recipients of international aid (except for Israel), with above-average political stability and below-average indigenous population density (Fig. 2). Overall, these countries have pledged relatively high proportions of their territories for restoration, some of them more than 70% (e.g. Liberia and Jordan). However, the total area pledged was one of the lowest among all archetypes (Fig. 1b, c).

Archetype 5 [North Africa and Middle East, moderate pledges]

This archetype included 16 countries (Supplementary Table 2) located in Sub-Saharan Africa (e.g., Mali), the Arabian Peninsula (e.g., Yemen), the Middle East (e.g., Iraq) and the Mediterranean basin (e.g., Algeria) (Fig. 1a). Countries in this archetype, which mainly spans desert areas, had the lowest proportion of land covered by forest, and the lowest NPP (proportionately). These countries were also characterized by having the lowest technology, and the highest population growth, and were generally recipients of international aid. Significantly, their governance was characterized by the lowest values for voice, political stability and regulatory quality, while exhibiting above-average values for indigenous land and population density (Fig. 2). These countries dedicated a relatively low proportion of their territories to restoration, but constituted the third largest total area in comparison with the other archetypes (Fig. 1b, c).

Archetype 6 [Eastern Europe and Caribbean, moderate pledges]

This archetype encompassed 14 countries (Supplementary Table 2) located primarily in eastern Europe (e.g., Belarus), the Baltics (e.g., Estonia), the Balkans (e.g., Serbia) and the Caucasus (e.g., Georgia) (Fig. 1a). They presented the most differentiating characteristics in the socio-economic and governance domains, for instance, they had among the highest incomes, education and life expectancies, and the lowest population growth. They were also recipients of international aid, and exhibited above-average tenure security and below-average proportions of indigenous land and population density (Fig. 2). These countries typically pledged both low proportions and low total areas of their territories for restoration (Fig. 1b, c).

Archetype 7 [Canada, Scandinavia, Australia/New Zealand, modest pledges]

This archetype included 8 countries (Supplementary Table 2) located predominantly in the ‘Global North’ (Fig. 1a). Countries in this archetype showed above-average values of NPP and protected area share for all the IUCN categories (specially I to III), but below-average share of agricultural land. They exhibited the highest technology and above-average education levels combined with the lowest population density and below-average GDP growth. These countries were some of the main donors of international aid. In terms of governance, this archetype had the highest values for voice, political stability and regulatory quality indexes, as well as of tenure security. The share of indigenous population was also above-average (Fig. 2). Despite the large landmasses of some of these countries, they committed the third lowest proportion of territory and total area for restoration (Fig. 1b, c).

Archetype 8 [Small European and Caribbean states, modest pledges]

This archetype included 21 small countries (Supplementary Table 2) located exclusively in Europe (e.g., Croatia) and the Caribbean (e.g., Jamaica) (Fig. 1a). They showed the lowest NPP, and below-average share of non-productive areas, protected areas and agricultural lands. In the socio-economic domain, this archetype had above-average mean income, and population density, below-average population growth, and the lowest GDP growth. Countries in this archetype were recipients of international aid. In terms of governance, they scored above-average values for voice, political stability and regulatory quality indexes (Fig. 2). These countries exhibited the second lowest restoration pledges among all archetypes in terms of both the proportions of their territories and total area, with many countries not pledging at all. (Fig. 1b, c).

Archetype 9 [Western Europe, South Korea, Japan, very low pledges]

This archetype encompassed 24 countries from the ‘Global North’ (Supplementary Table 2), including all of western Europe, some eastern European countries (e.g., Poland), as well as South Korea and Japan (Fig. 1a). This archetype showed the most differentiating values for the socio-economic and governance indicators, with above-average technology and below-average population growth and GDP growth. These countries were the main donors of international aid. They also had above-average values for voice, political stability, regulatory quality and tenure security, while indigenous population and indigenous lands were among the lowest (Fig. 2). Countries exhibited the lowest restoration pledges among all archetypes (with many countries not pledging at all) in terms of both, area share and total area (Fig. 1b, c).

Telecoupling factors shaping nation restoration capacity

Figure 3 shows the net flow of embodied land per capita due to global trade relations to/from each archetype [Kruskall–Wallis: χ²= 58.626; P < 0.0001]. Four archetypes (2, 4, 8 and 9) were dominated by countries with mean positive values of eHANPP (i.e., net importers of embodied land). Counties within archetypes 4 (e.g., Israel), 8 (e.g., Bahamas) and most notably 9 (e.g., Germany), showed the mean and median positive values indicating that the majority of countries was found in the positive range (i.e., they were importers of embodied land). Differently, although archetype 2 showed a positive mean, the median was in the negative range indicating that some countries within that archetype act as importers of embodied land (e.g., USA) and others as exporters (e.g., Chile). Countries within archetypes 2, 4 and 9 committed on average less than 5% of their territories for restoration, with archetype 9 committing only 0.37%, while the average commitment in archetype 2 was the second largest from all archetypes. The rest of the archetypes had negative values of eHANPP, making them net exporters of embodied land. However, there were marked differences among and within archetypes. For example, countries within archetypes 3 (e.g., Kazakhstan), 5 (e.g., Libya) and 7 (e.g., Finland) showed clearer negative mean eHANPP values, indicating, on average, substantial exports of land from many countries within these archetypes. Interestingly, these archetypes presented large pledged areas, especially archetype 3 (more than 9%). Archetype 7 represented a special case because the majority of countries had values close to zero (although negative), while one outlier (Canada) pushed the mean into the negative, and thereby into the eHANPP exporter category. Countries within archetypes 1 and 6 showed slightly mean negative eHANPP values, with some countries acting as importers (e.g., Rwanda) and others as exporters of embodied land (e.g., Ghana), and some of them (from archetype 1) showing large pledged areas (Fig. 1b; 28.7% of land on average). Our results show that in general the ‘Global North’ is a net importer of land and the ‘Global South’ a net exporter, and that the flow of eHANPP across the globe is highly unequal. Importantly, our model linked restoration with increases in NPP, but did not differentiate between types of restoration nor attempted to quantify the amount of land embodied in particular restoration activities. Rather, the eHANPP analysis is intended to act as a complement to the identification of archetypes of social-ecological conditions; together, these analyses suggest a “double pressure” placed on the ‘Global South’ to both export productive land to the ‘Global North’ and restore extensive amounts of land to meet global restoration targets–even though they often lack the enabling conditions to do so.

The solid red line represents the mean, and the solid black line represents the median. Positive values indicate countries within archetypes importing embodied land, whereas negative values indicate countries exporting embodied land. The mean percentage of the countries’ area per archetype pledged for restoration is indicated on top of the box plots. Note that data on restoration pledges were not used to generate the archetypes, but to contextualize and compare them. Countries are depicted according to an International Monetary Fund region (shape) and North-South (color) categorization.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed archetypical biophysical, socio-economic and governance conditions and their relation to national restoration pledges. In addition, we contrasted how these archetypes related to restoration pledges and telecoupled embodied flows of land. Our analyses revealed archetypes of conditions (both local and global) that might enable or hinder restoration, highlighting large global disparities between nations and their role and capacity to effectively contribute to global restoration commitments.

When determining opportunities for restoration, many global analyses have looked primarily at biophysical potential14. Resulting maps of “global restoration opportunities” and associated archetype analyses tend to cluster countries with large land areas deemed biophysically amenable to restoration15. However, our analysis revealed that despite archetype similarities in the biophysical domain, countries within those archetypes can be very different regarding their socio-economic and governance characteristics. Favorable biophysical indicators may not, in all cases, translate to a high capacity for restoration. From our findings, we identified three broad groups of countries with substantially different restoration potentials: (1) High biophysical potential with mixed enabling/hindering socio-economic-governance conditions; (2) Average biophysical potential with favorable socio-economic-governance conditions; and (3) Low biophysical potential with mixed enabling/hindering socio-economic-governance conditions.

The first group included archetypes 2, 3 and 7, and showed overall high biophysical potential, and mixed enabling/hindering socio-economic and governance conditions for restoration. Thus, comparisons between these archetypes suggest major differences in restoration capacity. For example, archetypes 2 and 3 differed with respect to the Human Development index indicators of income, education and life expectancy, as well as indigenous population, factors understood as important for restoration4,35. In particular, archetype 9 had the lowest value for the Human-Development Index indicators, as well as higher levels of population growth – conditions generally considered to negatively influence restoration36. Thus, although both archetypes had high biophysical potential for restoration, countries in archetype 2 showed a more favorable socio-economic context.

Comparisons between archetypes 2 and 7 yielded particularly interesting insights. Archetype 7 comprised only countries from the ‘Global North’ (e.g., Australia), while archetype 2 comprised only countries from the ‘Global South’ (e.g., Brazil), with the exception of the United States. Although archetype 7 presented much clearer enabling factors– particularly governance conditions–, countries from archetype 2 have made more substantial restoration pledges (9.55% on average; Fig. 1b). This contradictory finding could be attributable to the higher values of forest share in archetype 2. In this sense, a higher forest cover may command more attention as many initiatives worldwide are focused on forest landscape restoration37. However, even though the higher forest cover in archetype 2 might inspire larger restoration pledges, the higher population growth of archetype 2 could hinder restoration efforts, as they exacerbate competition for space in a context of global extractivist pressures on land4,36,38. A similarity between archetypes 2 and 7 is the higher proportion of indigenous population contrasted with on-average share of indigenous land, suggesting additional impediments for restoration as indigenous-managed land is crucial for conservation and restoration worldwide39,40,41. Reasons for these differences could be the existence of a vertical flow of “unequal ecological exchange” (i.e., embodied land) between the countries in these archetypes28,42,43. Though the ‘Global North’ countries of archetype 7 theoretically demonstrate better enabling factors for restoration, the dynamics underpinning unequal ecological exchange push restoration to other, less capacitated, places.

The second group was composed by archetypes 6 and 9 which showed average biophysical potential for all indicators and overall favorable enabling socio-economic and governance conditions. A distinction between these archetypes—despite similarities in the biophysical and socio-economic-governance conditions and in the geographies where they are located— is that archetype 6 was composed mostly of Global South countries while archetype 9 was composed of mostly of Global North countries. The average biophysical potential was complemented by favorable enabling conditions in the socio-economic domain, including shrinking populations considered to put strains on limited environmental resources36,44 and positive technology adoption considered to enable some types of restoration interventions – especially in archetype 945,46. However, economies were not expected to grow particularly in archetype 9, indicating less probability of investments in restoration as less wealth is accumulated and available47. Despite bad performance of their economies, countries in archetype 9 were donors while countries in archetype 6 (and other archetypes) were recipients of international aid raising questions about who benefits from flows directed towards restoration. Governance conditions were also favorable in both archetypes, except for indigenous population and indigenous land, which were among the lowest among all archetypes (Fig. 2). Notably, however – and in line with our observations of ecologically unequal exchange highlighted above – despite the potentially enabling biophysical, socio-economic and governance conditions for restoration, these archetypes did not contribute important restoration pledges (Fig. 1b).

The third group included archetypes 1, 4, 5 and 8 and was composed of a majority of ‘Global South’ countries (Fig. 1), showed low biophysical potential, and mixed enabling/hindering socio-economic and governance conditions. In the biophysical domain, agricultural share played an important role. For instance, archetype 1 showed the highest agricultural share, which could indicate potential conflicts with restoration. While agriculture and restoration are by no means incompatible – indeed, many successful restoration projects and interventions take place in agriculture-dominant landscapes – much agriculture in these geographies is driven by global markets and characterized by extractivist practices48,49. International agreements, which often view agricultural lands as ‘opportunities’ for restoration, risk exerting a double pressure in which agriculture and restoration compete for limited available NPP, and therefore both appropriate it (i.e., HANPP). Archetype 5 showed the largest proportion of non-productive areas (Fig. 2). In these mostly arid countries, where agriculture is concentrated into small areas, restoration is conditioned by primary productivity, water availability, and changes in land uses (which might generate conflicts with agriculture)41,50. In the socio-economic and governance domains, both archetypes 1 and 5 showed a number of hindering conditions, including a lower technology index, as well as lower political stability, regulatory quality or tenure security. The latter is considered foundational for restoration50,51, and another source of conflict. Contrastingly, these archetypes presented a higher share of indigenous lands, which is potentially an enabling condition for restoration. Safeguarding indigenous rights, land tenure, and access to resources would likely also help secure long-term benefits of restoration in these archetypes40. Archetype 6 showed more favorable governance conditions, including voice, political stability and tenure security. In contrast with archetypes 1 and 5, which showed GDP growth and pledged high proportions of their territories, archetype 8 countries were not projected to have high GDP growth – suggesting less investments in restoration initiatives –, and they committed a scarce area share for restoration (1.26% on average; Fig. 1b). Conversely, archetype 4, although having fewer favorable conditions (with the exception of technology), pledged on average a relatively higher proportion of territory for restoration (in some cases above 70%; Fig. 1b).

Sustainability literature identifies global appropriation of NPP as a root cause of social-ecological degradation, and has documented unequal ecological exchange between centers of wealth in the ‘Global North’ and ‘extractivism areas’ in the ‘Global South’42,43. Our results similarly suggest that unequal eHANPP exchange (in terms of land) in a telecoupled world poses a possible challenge to global restoration goals, and suggests an inconsistency between what countries pledge to restore in the international arena and their ability to carry out pledged restoration work within their borders. Our results show a clear imbalance in terms of eHANPP exchange, with countries in western Europe, and far-east Asia acting as net eHANPP importers, while many countries in the ‘Global South’ conform to archetypes that generally function as net exporters of embodied land, although there is variability (see Fig. 3).

In this context, embodied land represents areas with the potential to support restoration dependent on biomass and NPP, but also areas that support increasing consumption through ‘unequal ecological exchange’ driven by extractivism29. Paradoxically, many of the countries in the importers group (e.g. archetype 9) commit only minor portions of their territories for restoration, leaving the ‘restoration burden’ to countries that are already major exporters of embodied land (e.g. archetype 1, Fig. 3). The question then arises: is it feasible for countries in the ‘Global South’ to be the primary source of land for restoration, while still remaining the dominant producers of primary productivity for the ‘Global North’?

Our study suggests a clear mismatch between both the prevailing enabling and hindering conditions for restoration within archetypes and the global flows of eHANPP with current restoration pledges. Two main conclusions emerge from our analyses:

-

I.

Archetypes with the most favorable internal conditions for restoration, particularly governance conditions, have made only modest pledges to global restoration efforts, whereas several archetypes with much less favorable conditions have made major restoration pledges in both relative and absolute terms (Fig. 1; Fig. 3). This phenomenon is exemplified most clearly in the cases of archetypes 9 (e.g., Germany) and 1 (e.g., Togo).

-

II.

Archetypes with the highest restoration pledges in relative and absolute terms are those already exporting embodied land to other countries. Concomitantly, countries within archetype 9 behave as the largest net importers of land but have committed only modest restoration pledges (Fig. 1; Fig. 3).

Together, these results suggest that the countries best positioned to undertake successful restoration projects largely outsource the work of restoration–often vis-a-vis financial aid–to countries with difficult socio-economic or political conditions. The difficulty of accomplishing ‘successful’ restoration projects in these nations is further compounded by pressure that ‘Global North’ countries doubly exert on the ‘Global South’. The end result is that less powerful, less capacitated countries are tasked both with restoring important amounts of land and exporting NPP in the form of raw commodities–in some cases through intensive, extractivist activities that clash with restoration in practice.

There are compelling reasons to concentrate restoration activities in tropical countries in the Global South, as these geographies contain highly biodiverse ecosystems, and–by some accounts–are the sites where the majority of landscape degradation is currently taking place. Nevertheless, the ‘Global North’ cannot have its cake and eat it too; it cannot continue to exert a double pressure on the ‘Global South’ to both export productive land and restore extensive amounts of land to meet global restoration targets, particularly given that Global South countries often face numerous hindering conditions. Our analysis highlights the need to account for a host of social, economic, and political factors alongside biophysical factors when considering where restoration ought to take place. Moreover, special attention is required regarding the creation of context-specific policies and management practices that ensure that such restoration efforts are successful from both an ecological and social perspective. More comprehensive accounting raises serious questions about where large-scale restoration is not only needed but also achievable, and about who benefits from existing flows of resources and the associated pressures to restore31,33.

In archetype analysis, it is common that not all clusters conform to expectations or intuition (e.g., see archetype 2). In this sense, it is important to interpret the results cautiously, acknowledging that archetype analysis simply reflects recurrent patterns in the input data, and this will not always match with prior expectations. Still, as long as such problems occur only for some clusters, archetype analysis remains highly effective for summarizing complex information (here, 21 variables across dozens of countries) in relatively simple, accessible terms. This was particularly useful in our study to identify global restoration challenges emerging from diverse within-country social-ecological conditions, within a context of variable restoration pledges and land telecouplings. In this regard, indicators were chosen based on our goal to capture a balanced mixture of reliable socio-economic, governance, and biophysical dimensions. While it is true that not all indicators specifically characterize particular archetypes, this could not have been known before the analysis.

In addition, basing the within- and between-country assessment on an archetype analysis and the HANPP framework32,52,53 might hinder detailed country-level analyses, and hide differences in data quality for different parts of the world. While our indicators were based on recognized international databases (Supplementary Table 4), some of them (e.g. indigenous land tenure) require a nuanced evaluation as they stem from multiple sources. Additionally, for the purposes of our analysis we generally treated agriculture and restoration as competing land uses. However, many restoration projects take place to varying degrees of success in agricultural landscapes, and in those cases, these two land uses do not necessarily compete with one another. Future research could expand similar methods to elucidate enabling and hindering conditions specifically for restoration in mixed-use landscapes. Finally, our indicators for forest and agriculture share are derived from World Bank data (Supplementary Table 4), which classifies plantations as forests. The World Bank also excludes trees on agriculture land from forest area percentage data, thereby underreporting forest cover that comes from agroforestry systems - some of which are much more complex, ecologically valuable, and resilient than the monoculture plantations that are counted as forests. Finally, the objects of ecosystem restoration span beyond terrestrial forest ecosystems, and in particular, include aquatic ecosystems (for which NPP alone would be an inadequate measure). Future research could again build upon our methods to analyze social-ecological conditions for a broader set of ecosystems.

Of note is that the division between the ‘Global South’ and ‘Global North’ as used in this paper is not strictly based on geographical location but rather on economic, social, and political characteristics. ‘Global North’ broadly comprises Northern America and Europe, Israel, Japan and South Korea, as well as Australia and New Zealand54. ‘Global South’ is a term broadly used to delineate countries with lower levels of economic/industrial development. We adopt these terms sparingly to ensure legibility and accessibility to scholars and practitioners who are most likely to make use of our analysis, and to communicate broad patterns of existing inequalities. We acknowledge, however, that these are descriptively inaccurate, homogenizing, and ultimately problematic terms, rooted in neo-colonial power structures55 and we refrain from using them as descriptors for our archetypes. By grouping countries into more descriptive archetypes, our paper helps to dismantle these terms and advance a more accurate, multidimensional pathway for clustering countries according to a broad range of descriptors. Importantly, we recognize that the systematic assessment of eHANPP in a context of restoration is not the only way to examine unequal geopolitical relationships. However, it fits well with our approach of generating global maps, and has yielded meaningful results in several other global-scale assessments (e.g. refs. 56,57).

Methods

Data collection

For the identification of archetypes of within-country social-ecological conditions for ecosystem restoration we collected data on 21 indicators for 207 countries or officially recognized territories for the latest available year (Supplementary Table 1). Indicator selection was based on recent literature suggesting the inclusion of biophysical, socio-economic and governance domains (Supplementary Table 2) when investigating restoration in order to account for social-ecological contexts and equity issues21,27,53.

We adopted indicators used by other scholars (e.g. refs. 4,58), and augmented them with additional land tenure and indigenous data indicators. In total, we employed seven indicators to describe biophysical conditions, eight to represent socio-economic conditions and six to describe governance conditions. To contextualize the archetypes of within-country conditions (not to generate them), we included two additional indicators to evaluate: (1) national restoration pledges (as the amount of land committed to restoration); and (2) between-country conditions (as the embodied human appropriated net primary productivity – eHANPP –, see refs. 42,52,59). The logic here was to highlight the amount of land derived from NPP that is embodied (i.e., consumed) by a given country in any other country. The capacity for doing ecosystem restoration strongly depends on NPP. Trade of embodied land (i.e., via global telecouplings) might undermine ecosystem restoration because of competition for primary productivity.

Indicators were collected from open source databases compiled by international organizations with recognized legitimacy, such as public institutions, agencies, and programs related to the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and the World Bank, as well as other international organizations and scientific literature. We retrieved and selected those indicators that: i) demonstrated high representational capacity (avoiding high collinearity), ii) had available information for many countries, and iii) were based on recent data and in case of trends (population growth) contained projections for the next 20 years.

Data analysis

Tests for the normality of the distribution of all 21 indicators were performed. The indicators that did not follow a normal distribution or had negative values were transformed using the bestNormalize package60. After normalization, the indicators were rescaled (0-1) using z-score normalization to obtain zero mean and unit of variance, which removed the different indicator units61. For the identification of archetypes of countries, we carried out a hierarchical cluster analysis–using the Ward method and Manhattan distance– based on the 21 indicators describing within-country conditions. For the selection of the optimal number of archetypes we used the Davies-Bouldin index62.

Then, we characterized the archetypes by averaging indicator values across all countries in a specific archetype, and then calculated the deviation (in standard deviations) of the archetype mean to the overall mean of all the studied countries. Thus, positive deviances refer to above average values, and negative deviances to below average values, regarding the overall mean for all countries (Fig. 2). We further contextualized the archetypes by averaging (1) the country area pledged to restoration (see Fig. 1b, from highest to lowest in percentage values, and Fig. 1c in absolute values), and (2) the country net exchange of embodied land – i.e., eHANNP – (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table 3). We computed a Kruskall–Wallis test to assess if the differences between archetypes in the average area pledged to restoration and eHANPP were statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with R63.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data on the 21 country-level indicators used to develop the archetype analysis, and 2 additional indicators that support the findings of this study are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1404418064. Data sources are listed in the Supplementary Table 4.

Code availability

The code used for this work is available at https://github.com/benra1990/connected_restoration. R version 4.3.3 was used for all analyses of this study. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

IPBES. Global Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity (IPBES secretariat, 2019).

IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. In Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds, Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero). IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/ (2023).

United Nations Environment Programme. The UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration 2021-2030: Scaling up Restoration of Degraded and Destroyed Ecosystems. https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/30919 (2019).

Löfqvist, S. et al. How Social Considerations Improve the Equity and Effectiveness of Ecosystem Restoration. BioScience 73, 134–148 (2023).

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. A New Universal Global Alliance For Biodiversity Protection Established In Bonn. https://www.cbd.int/kb/record/pressRelease/48003?RecordType=pressRelease (2008).

Goffner, D., Sinare, H. & Gordon, L. J. The Great Green Wall for the Sahara and the Sahel Initiative as an opportunity to enhance resilience in Sahelian landscapes and livelihoods. Reg. Environ. Change 19, 1417–1428 (2019).

Nature Editorial. Get Africa’s Great Green Wall back on track. Nature 587, 8 (2020).

Messinger, J. & Winterbottom, B. African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative (AFR100): Restoring 100 Million Hectares of Degraded and Deforested Land in Africa (FAO, 2022).

UNEA. United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030) (UNEA, 2019).

Sewell, A., van der Esch, S. & Löwenhardt, H. Goals and Commitments for the Restoration Decade (PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, The Hague, 2020).

UNCCD. Global Land Outlook (UNCCD, 2022).

Osborne, T. et al. The political ecology playbook for ecosystem restoration: Principles for effective, equitable, and transformative landscapes. Glob. Environ. Change 70, 102320 (2021).

Laestadius, L., Buckingham, K., Maginnis, S. & Saint-Laurent, C. Before Bonn and beyond: the history and future of forest landscape restoration, 66, (Unasylva, 2015).

Strassburg, B. B. N. et al. Global priority areas for ecosystem restoration. Nature 586, 724–729 (2020).

Bastin, J.-F. et al. The global tree restoration potential. Science 365, 76–79 (2019).

Schmidt-Traub, G. National climate and biodiversity strategies are hamstrung by a lack of maps. Nat. Ecol. Evolution 5, 1325–1327 (2021).

McElwee, P. Reforesting “Bare Hills” in Vietnam: Social and Environmental Consequences of the 5 Million Hectare Reforestation Program. AMBIO: A J. Hum. Environ. 38, 325–333 (2009).

Qiu, S., Peng, J., Zheng, H., Xu, Z. & Meersmans, J. How can massive ecological restoration programs interplay with social-ecological systems? A review of research in the South China karst region. Sci. Total Environ. 807, 150723 (2022).

Tedesco, A. M. et al. Beyond ecology: ecosystem restoration as a process for social-ecological transformation. Trends Ecol. Evolution 38, 643–653 (2023).

Sigman, E. Safeguarding Biodiversity Islands in Northern Ethiopia Amidst Political Change. In Biodiversity Islands: Strategies for Conservation in Human-Dominated Environments (ed. Montagnini, F.) vol. 20 647–674 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2022).

Sigman, E. & Elias, M. Three Approaches to Restoration and Their Implications for Social Inclusion. uwpress. org. Ecol. Restor. 39, 1–2 (2021).

Schultz, B. et al. Recognizing the equity implications of restoration priority maps. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 114019 (2022).

Wells, H. B. M. et al. Equity in ecosystem restoration. Restoration Ecol. 29, e13385 (2021).

Chazdon, R. L., Wilson, S. J., Brondizio, E., Guariguata, M. R. & Herbohn, J. Key challenges for governing forest and landscape restoration across different contexts. Land Use Policy 104, 104854 (2021).

Pfeifer, M. et al. A systems approach framework for evaluating tree restoration interventions for social and ecological outcomes in rural tropical landscapes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 378, 20210111 (2023).

Fischer, J., Riechers, M., Loos, J., Martin-Lopez, B. & Temperton, V. M. Making the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration a Social-Ecological Endeavour. Trends Ecol. Evol. 36, 20–28 (2021).

Frietsch, M., Loos, J., Löhr, K., Sieber, S. & Fischer, J. Future-proofing ecosystem restoration through enhancing adaptive capacity. Commun. Biol. 6, 377 (2023).

Givens, J. E., Huang, X. & Jorgenson, A. K. Ecologically unequal exchange: A theory of global environmental in justice. Sociol. Compass 13, e12693 (2019).

Bioeconomy and Global Inequalities: Socio-Ecological Perspectives on Biomass Sourcing and Production (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68944-5.

Tu, C., Suweis, S. & D’Odorico, P. Impact of globalization on the resilience and sustainability of natural resources. Nat. Sustain 2, 283–289 (2019).

Chen, W., Kang, J.-N. & Han, M. S. Global environmental inequality: Evidence from embodied land and virtual water trade. Sci. Total Environ. 783, 146992 (2021).

Höhl, M. et al. Forest Landscape Restoration—What Generates Failure and Success? Forests 11, 938 (2020).

Kuemmerle, T., Kastner, T., Meyfroidt, P. & Qin, S. Conservation Telecouplings. in Telecoupling (eds. Friis, C. & Nielsen, J. Ø.) 281–302 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11105-2_15.

Carmenta, R. et al. Connected Conservation: Rethinking conservation for a telecoupled world. Biol. Conserv. 282, 110047 (2023).

Elias, M. et al. Ten people‐centered rules for socially sustainable ecosystem restoration. Restoration Ecol. 30, e13574 (2022).

Cafaro, P., Hansson, P. & Götmark, F. Overpopulation is a major cause of biodiversity loss and smaller human populations are necessary to preserve what is left. Biol. Conserv. 272, 109646 (2022).

Stanturf, J. A., Palik, B. J. & Dumroese, R. K. Contemporary forest restoration: A review emphasizing function. For. Ecol. Manag. 331, 292–323 (2014).

Hughes, A. C. et al. Smaller human populations are neither a necessary nor sufficient condition for biodiversity conservation. Biol. Conserv. 277, 109841 (2023).

Garnett, S. T. et al. A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nat. Sustain. 1, 369–374 (2018).

Camino, M. et al. Indigenous Lands with secure land-tenure can reduce forest-loss in deforestation hotspots. Glob. Environ. Change 81, 102678 (2023).

Erbaugh, J. T. et al. Global forest restoration and the importance of prioritizing local communities. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1472–1476 (2020).

Dorninger, C. et al. Global patterns of ecologically unequal exchange: Implications for sustainability in the 21st century. Ecol. Econ. 179, 106824 (2021).

Hickel, J., Dorninger, C., Wieland, H. & Suwandi, I. Imperialist appropriation in the world economy: Drain from the global South through unequal exchange, 1990–2015. Glob. Environ. Change 73, 102467 (2022).

Maja, M. M. & Ayano, S. F. The Impact of Population Growth on Natural Resources and Farmers’ Capacity to Adapt to Climate Change in Low-Income Countries. Earth Syst. Environ. 5, 271–283 (2021).

Brown, V. S. et al. A global review of seed enhancement technology use to inform improved applications in restoration. Sci. Total Environ. 798, 149096 (2021).

Perring, M. P. et al. Advances in restoration ecology: rising to the challenges of the coming decades. Ecosphere 6, art131 (2015).

Li, S., Xie, J. & Paudel, B. Do Ecological Restoration Projects Undermine Economic Performance? A Spatially Explicit Empirical Study in Loess Plateau, China. Remote Sens. 15, 3035 (2023).

Chagnon, C. W. et al. From extractivism to global extractivism: the evolution of an organizing concept. J. Peasant Stud. 49, 760–792 (2022).

Veltmeyer, H. & Ezquerro-Cañete, A. Agro-extractivism. J. Peasant Stud. 50, 1673–1686 (2023).

Yang, Q., Liu, G., Agostinho, F., Giannetti, B. F. & Yang, Z. Assessment of ecological restoration projects under water limits: Finding a balance between nature and human needs. J. Environ. Manag. 311, 114849 (2022).

Chigbu, U. E. et al. Tenure-restoration nexus: a pertinent area of concern for land degradation neutrality. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 57, 101200 (2022).

Kastner, T. et al. Land use intensification increasingly drives the spatiotemporal patterns of the global human appropriation of net primary production in the last century. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 307–322 (2022).

Marshall, A. R. et al. Fifteen essential science advances needed for effective restoration of the world’s forest landscapes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 378, 20210065 (2023).

UNCTAD. Country Classifications. https://unctadstat.unctad.org/en/classifications.html (2023).

Sinah Theres Kloß The Global South as Subversive Practice: Challenges and Potentials of a Heuristic Concept. Glob. South 11, 1 (2017).

Oteros-Rozas, E., Ruiz-Almeida, A., Aguado, M., González, J. A. & Rivera-Ferre, M. G. A social–ecological analysis of the global agrifood system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 26465–26473 (2019).

Václavík, T., Lautenbach, S., Kuemmerle, T. & Seppelt, R. Mapping global land system archetypes. Glob. Environ. Change 23, 1637–1647 (2013).

Fagan, M. E., Reid, J. L., Holland, M. B., Drew, J. G. & Zahawi, R. A. How feasible are global forest restoration commitments? Conserv. Lett. 13, e12700 (2020).

Haberl, H., Erb, K.-H. & Krausmann, F. Human Appropriation of Net Primary Production: Patterns, Trends, and Planetary Boundaries. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 39, 363–391 (2014).

Peterson, A. Package ‘BestNormalize’. Normalizing Transformation Function (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2023).

Wickham, H. & Seidel, D. Package ‘Scales’. Scale Functions for Visualization (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2022).

Levers, C. et al. Archetypical patterns and trajectories of land systems in Europe. Reg. Environ. Change 18, 715–732 (2018).

R. Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2023).

Benra, F. Ecosystem restoration pledges in a telecoupled and unequal world v1.0.1. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14044181 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Emily Sigman gratefully acknowledges the support of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. Manuel Pacheco-Romero thanks the Spanish Ministry of Universities and NextGenerationEU for the Margarita Salas fellowship. This work did not receive funding.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

In the conceptualization phase, Felipe Benra and Joern Fischer jointly formulated the foundational idea. Felipe Benra led the study and conducted the analyses. Girma Shumi helped with data collection. Maria Brück contributed to analyzing the data. Emily Sigman significantly contributed to the writing and review processes. Manuel Pacheco-Romero, David J Abson and Marina Frietsch provided valuable feedback to the writing and review processes which helped improved the draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jialiang Cai, Heike Langenberg. [A peer review file is available.]

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Benra, F., Brück, M., Sigman, E. et al. National ecosystem restoration pledges are mismatched with social-ecological enabling conditions. Commun Earth Environ 5, 731 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01909-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01909-3

This article is cited by

-

Towards just and transformative social–ecological restoration

Nature Sustainability (2025)

-

Survival and performance of seedlings planted for forest landscape restoration in the Oromia region of Ethiopia

Discover Agriculture (2025)