Abstract

Paleoclimatic measurements serve to understand Earth System processes and evaluate climate model performances. However, their spatial coverage is generally sparse and unevenly distributed across the globe. Statistical interpolation methods are the prevalent techniques to grid such data, but these purely data-driven approaches sometimes produce results that are incoherent with our knowledge of the physical world. Physics-Informed Neural Networks follow an innovative approach to data analysis and physical modeling through machine learning, as they incorporate physical principles into the data-driven learning process. Here, we develop a machine-learning algorithm to reconstruct global maps of atmospheric dust surface deposition fluxes from paleoclimatic archives for the Holocene and Last Glacial Maximum periods. We design an advection-diffusion equation that prevents dust particles from flowing upwind. Our physics-informed neural network improves on kriging interpolation by allowing variable asymmetry around data points. The reconstructions display realistic dust plumes from continental sources towards ocean basins following prevailing winds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The deposition of dust on the Earth’s surface provides the terrestrial biosphere and surface ocean with micronutrients, affecting biogeochemical cycles1. Additionally, dust particles can reflect or absorb incoming solar radiation, leading to changes in surface temperature and atmospheric circulation patterns2. Variability in the atmosphere’s dust concentration may have affected past climate change, such as glacial-interglacial cycles3.

Previous efforts to simulate dust deposition under past climatic conditions were conducted using various global climate models4,5,6,7,8. The complex nature of mineral dust aerosol emission makes it difficult to represent vertical dust fluxes accurately in weather and climate models9. Hence, there are important differences in atmospheric dust load and spatial distribution among various dust simulations, even under modern conditions2,10.

The Dust Indicators and Records of Terrestrial and Marine Paleoenvironments (DIRTMAP) database was designed to serve as a global validation dataset of simulations of the paleo-dust cycle with Earth System Models (ESM)11. The dataset includes information on aeolian dust in ice cores, marine sediment cores, and loess-paleosol sections for average Holocene and Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) climatic conditions. These periods are characterized by low and high deposition rates, respectively. Only a few hundred sites around the world met the quality requirements to be included in the DIRTMAP database. Updated versions of this dataset12,13 are still the reference against which paleoclimatic dust simulations are compared. However, these data are unevenly distributed worldwide and unsuitable as boundary conditions or input fields for climate models. In practice, the kriging algorithm is the most appropriate geostatistical technique to interpolate the data across the globe10. These global interpolations are in gridded lat-lon format and can be used as input for climate simulations14,15,16. However, the kriging algorithm distributes the influence of a measured data point symmetrically along the anisotropy axis, thus spreading the influence of observations both upwind and downwind. This isotropy is not desirable at sites that are close to source dust regions. As an example, dust emitted in Patagonia in South America should be transported towards the South Atlantic in the direction of the Southern Westerly Winds (SWW) and not against these winds towards the South Pacific.

Deep neural networks could theoretically capture the behavior of global dust deposition if they are trained on enormous datasets. However, copious amounts of data are usually unavailable in the paleoclimatic context. For example, the DIRTMAP database contains a few hundred sites for both Holocene and LGM conditions, which is far from enough to train a neural network correctly. The idea of a Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) is to add information about the physical processes to the training algorithm so that predictions are restricted to physically realistic outcomes17. This physics-data fusion is achieved by adding a model loss term to the neural network that measures the consistency of the estimation with regard to a partial differential equation (PDE). In this study, we develop a PINN that optimizes the gridded field of global dust depositions according to two objectives: fitting the data and satisfying the PDE model.

PINNs were recently introduced as a powerful technique in situations where limited data are available and the physical processes are partially known18. The versatility of PINNs allows for different types of uncertainties, such as measurement errors in the data and unknown parameters in the PDE model19. Specifically, unknown parameters in the PDE or boundary conditions can be added to the neural network and optimized during the training phase, a procedure also known as an inverse problem or model discovery20,21. These capabilities of the PINN are crucial to our goal of reconstructing global dust deposition since the empirical database has considerable measurement errors, and several variables of the PDE are unknown in paleoclimatic settings.

While PINNs have attracted much attention from researchers, there are still many limitations in this field of scientific machine learning22. One prominent challenge is the application of PINNs to real-world data from field observations. Most research involves solving PDEs with validation against analytical solutions23 and numerical solvers such as finite element methods24. Often, the ground truth comes from synthetic data generated by high-fidelity simulations25. Among the few examples of PINNs for empirical data, we mention earthquake hypocentres26, fluid mechanics27, cardiovascular flow28, and the covid-19 epidemic29. While algorithmic innovations develop rapidly, there is still a large untapped potential for artificial intelligence and machine learning in the geosciences30 and climate models31. For example, innovative approaches such as the PINN may improve global reconstructions of paleoclimatic variables substantially as compared to geostatistical approaches, and with much lower computational costs than coupled climate simulations.

In this study, we design a PINN to reconstruct a global dust deposition map from empirical paleoclimatic datasets with dust transport guided by physical processes such as advection and diffusion. The results are as good as kriging interpolations in regions with high data availability and, most importantly, substantially improve the physical realism of the calculations in data-sparse regions. Plumes of high dust concentration are accurately reconstructed along the prevailing westerlies at mid-latitudes and trade winds near the equator. These achievements confirm that PINNs can live up to their high expectations by combining data analysis and physical modeling within a single framework, even in realistic and challenging settings in geosciences such as reconstructing dust deposition fields from paleoclimatic records.

Results and discussion

We designed a PINN for global dust deposition rates and reconstructed a global map from the paleoclimate dust flux measurements collected in the DIRTMAP database for the Holocene and LGM periods10.

Global dust deposition reconstruction

We reconstructed the global dust deposition rates with our custom-built PINN algorithm and a dedicated kriging interpolation from ref. 10. The results in Fig. 1 display the reconstructions along with the 397 measurement points for the Holocene and the 317 measurements under LGM conditions. The PINN calculates the qualitative patterns of dust flow correctly, with high dust deposition values in the expected regions, such as the Sahara, East Asian deserts, North America, and Patagonia. The polar areas and oceans have low deposition rates as they are further away from major dust sources. We note that both the kriging interpolation and PINN calculation show minor dust levels in Australia and New Zealand for both Holocene and LGM conditions. This is because both are based on the same empirical dataset from 2015 that does not include continental information about this region10. Furthermore, the higher concentrations during the LGM compared to Holocene conditions are also visible in the reconstructions. Hence, the results confirm that the expected first-order features of global dust depositions are modeled correctly.

Downwind dust flow in data-sparse regions

As is common in paleoclimatology, global datasets are biased towards regions conducive to field campaigns. Hence, large parts of the world have no measurements or are sparsely covered by few data points. This lack of empirical data yields large uncertainties in geostatistical approaches like kriging interpolation10. Indeed, Fig. 1c, d display numerical artifacts such as stripes and discontinuities in kriging’s reconstructions in data-sparse regions such as the oceans in the southern hemisphere. In contrast, the PINN’s calculated maps are smooth around the globe and accurately model the sphericity of the Earth.

Most importantly, the PINN models the physics of downwind dust flow accurately. The kriging interpolation is isotropic and displays symmetric peaks of dust concentration around the major sources. In contrast, the PINN includes a physical model for advection and diffusion and reconstructs the expected dust plumes along the dominant wind direction. For example, dust from the Patagonian deserts is transported along the SWW towards the Atlantic Ocean.

Reconstruction in regions with uncertain data

Any global reconstruction algorithm has to fit the empirical data well in regions with sufficient measurements. However, the overfitting of data clusters has to be avoided since data come with large measurement errors and depend on local geographic conditions that are out of the scope of reconstructions on a global scale. For example, loess data in China may vary considerably between nearby measurement sites, with differences in deposition rate that may reach up to 80% in some cases13. Our goal is to reconstruct a global dust deposition map with a resolution of a few degrees in latitude and longitude, a scale at which diffusion of dust yields smooth fields. The physics-based loss term of the PINN effectively regularizes the reconstructions, also near the clusters of uncertain data points.

Figure 2 compares the empirical dataset, our PINN calculation, and the kriging interpolation of the dust fluxes. In general, the PINN and kriging fit well with the data in the measurement locations, with low values of the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). Furthermore, the estimations of the dust fluxes in the data points are consistent between the two computational approaches. We emphasize that lower statistical values of the data fit do not necessarily mean that the reconstruction is improved. That is, paleoclimatic data have considerable measurement errors and are biased toward locations where field experiments are possible, e.g., ice caps, loess fields, and high-sedimentation oceanic regions. The almost identical statistical error measures of the PINN and kriging to the empirical data confirm that the PINN performs as well as kriging in data-rich regions of the global reconstruction.

The values of dust deposition rate are in log(g/m2/a) as in Fig. 1. The results of the PINN and kriging are evaluated at the locations of the empirical dataset. The top panels compare the empirical dataset with the PINN calculation. The middle panels compare the empirical dataset with kriging interpolation at the empirical locations. The bottom panels compare the PINN calculation with kriging interpolation. The left panels correspond to the Holocene and the right panels use LGM conditions.

Discussion on PINN’s results

The PINN is an innovative approach cleverly combining data analysis with physical models. It promises to become a competitive alternative to traditional geostatistical methods by enforcing physical principles in data reconstructions with reasonable calculation times on common computer facilities. At the same time, current research into scientific machine learning targets open questions about the PINN’s mathematical foundations and its merits in real-world settings. Our study confirms that PINNs can work with empirical datasets and improve upon dedicated statistical approaches such as kriging.

Comparison between PINN and kriging

Kriging interpolation techniques are the community standard for gridded reconstructions of paleoclimatic data of dust deposition on a global scale for the Holocene and LGM periods10,13,32. However, this geostatistical algorithm is isotropic and yields elevated uncertainties in data-sparse regions. This study shows that PINNs yield global reconstructions that, on the one hand, have a similar goodness of fit to empirical data in regions where measurements are available and, on the other hand, avoid unphysical results by enforcing dust to flow along dominant wind directions. Hence, PINNs improve upon kriging.

The global reconstruction maps in Fig. 1 confirm that both the PINN and kriging correctly model the first-order features of global dust deposition, with high rates in arid zones and lower values over the oceans. Furthermore, the statistical fits of the PINN and kriging reconstructions with the empirical data are within the same error ranges; see Fig. 2. Notice that the DIRTMAP database for dust deposition comes with substantial measurement errors, with relative differences up to 80% depending on the type of field experiment13. Hence, minor differences between computational results and empirical data are expected when considering models on a global scale. The observed differences between PINN calculation, kriging interpolation, and the empirical data are all well within the range of data uncertainties.

The main reason for using PINNs instead of kriging is that they include physical information in reconstructing global dust deposition maps from sparse data. Interpolation techniques such as kriging are symmetric, thus allowing dust to flow upwind in contradiction with physical laws. This problem is exacerbated in regions with low data availability where statistical approaches lack the information to reproduce dust fields accurately. The improved physical realism of the PINN is most visible in the ocean basins downwind from primary dust sources, such as the South Atlantic, North Atlantic, and North Pacific. Moreover, the diffusion phenomenon incorporated in the PINN generates a smoothing effect of outliers and tight clusters of data points, avoiding overfitting issues common to pure data-driven approaches.

As a prime example of improved realism, we highlight that Patagonian dust in South America is transported towards the South Atlantic Ocean by the SWW and not upwind towards the South Pacific Ocean. This expected plume towards the east is clearly visible in the PINN’s results; see Fig. 3. In contrast, the kriging interpolation for the Holocene displays high concentrations towards the northeast, which is inconsistent with the dominant eastward wind direction. In fact, it is an artifact due to the direction of the anisotropy ellipse in kriging, which is calculated globally and produces distinctive southwest-northeast streaks in the interpolation10. The kriging interpolation produces a zonal anisotropy ellipse and a broad and symmetric peak around Patagonia under LGM conditions.

The top panels as calculated with the PINN and the bottom panels with the kriging algorithm, for the Holocene (left panels) and LGM periods (right panels). The reconstructions are the same as in Fig. 1 but displayed for a smaller region.

Notably, the dust plume calculated by the PINN is well-focused east of the Patagonian sources and displays a transport pathway reaching the Indian Ocean and even the South Pacific. This advection in the southern hemisphere is particularly strong in the LGM, even stronger than in ESM simulations. While there are several data points in the South Atlantic and the Indian Ocean for the Holocene, there is no empirical data for the LGM in these regions. This lack of measurement sites makes it difficult to assess whether advection is over or under-estimated. However, this marked pathway may be realistic since studies that analyze the chemical composition of dust depositions have detected South American dust transported by the SWW all the way to the Southern Pacific Ocean during the LGM33.

Additional examples of dust being correctly transported downwind by the PINN include East Asia, where the Northern Westerly Winds (NWW) transports dust emitted from the central Asian deserts over the North Pacific towards Alaska. Finally, a strong improvement of the PINN over kriging is evident over the north and tropical Atlantic Ocean; the PINN simulates a transport of North American dust towards the North Atlantic following the NWW while also indicating a transport of Saharan dust towards the Caribbean, Central America, and the Amazonas, following the trade winds. In contrast, the kriging interpolation shows a transport of North American dust towards the tropical Atlantic against the prevailing easterlies. Saharan dust transport to the Amazon Forest has been evidenced for modern times34,35.

Verification of the PINN methodology

The PINN is a relatively recent algorithm that has spurred a very active research agenda among mathematicians and practitioners of computational simulations. Being an innovative technology, we assessed PINN’s versatility in handling sparse and irregular datasets and its predictive skill for paleoclimatic processes by four verification strategies.

The first indicator supporting the accuracy of the PINN is the consistency between the calculated and empirical data, as shown in the scatterplots in Fig. 2(a) and (b) for the Holocene and LGM, respectively. Second, we analyzed the statistical distribution of the calculated dust deposition rates, which is expected to be approximately log-normally distributed, as is the empirical dataset. The results presented in Supplementary Discussion 1 confirm that the PINN maintains the log-normal distribution of the data. In the third approach, we applied the PINN to simulated data from an ESM. The PINN’s calculations show excellent agreement with the simulated data on a 1-degree global grid; see Supplementary Discussion 2. Fourth, we analyzed the goodness of fit of the PINN with cross-validation on left-out empirical data and random subsets of simulated data; see Supplementary Discussion 3.

Outlook on PINNs for geosciences

The PINN provides a general framework for combining data analysis with physical models and promises to be beneficial for a broad range of applications in geosciences. Our study on PINNs for global dust depositions serves as a proof of concept for reconstructing physical fields from sparse, irregular, and uncertain datasets. We summarize several key advantages of PINNs. First, PINNs work well when limited data is available. In this study, we worked with only 397 and 317 measurements for the Holocene and LGM periods, respectively. Second, the physical model incorporated in the PINN design tends to regularize the solution and thus handles data uncertainties well, even when applied to tight clusters of nearby measurement locations. This smoothing effect is achieved without needing special preprocessing techniques, such as averaging small regions, which is standard in kriging. Third, the PINN handles unknown parameters in the physical model by estimating their value within the training of the neural network. For example, our PINN design included the estimation of the diffusion coefficient and deposition at the polar boundaries, which cannot be taken from direct measurements. The results presented in Supplementary Discussion 4 verify the accuracy of the estimations of unknown parameters in the physical model. Fourth, PINNs work naturally with data in a lat-lon format, and PDEs can easily be written in spherical coordinates to model the Earth’s surface. Fifth, training a PINN on datasets of several hundreds of measurements takes only a few minutes on a standard workstation.

One of the main challenges of the PINN approach is creating a robust and accurate neural network. Design choices such as the type of neural network, number of layers, and activation functions strongly impact the convergence during training36. These issues are due to PINNs solving a non-convex optimization problem with local minima37. Unfortunately, current research into guidelines for setting these technical parameters is still ongoing22. Hence, future research should explore other kinds of neural networks, such as graph networks38 and Fourier neural operators39. Another challenge is specifying the correct PDE for modeling the physical processes of interest. We chose to include convection and diffusion only, but more elaborate models could be incorporated in the future, such as the Navier-Stokes equations40. Finally, Bayesian PINNs can be investigated to quantify the prediction uncertainty due to noisy data41. The promising results of this study could also be extended in future research for emulating, downscaling, and forecasting other weather and climate processes42.

Methods

Data

The empirical data we use in this study are the surface dust deposition fluxes measured in marine sediment cores, ice cores, and loess deposits published in10, including the DIRTMAP database and some additional sites. The data are averaged dust deposition rates over the Holocene (last 12 thousand years) and LGM periods (between 19 and 26 thousand years ago) and consist of 397 and 317 measurements, respectively.

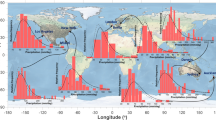

The global map of the measurement sites in Fig. 4 clearly shows the limited amount of paleoclimate data available for analysis. The data points are also irregularly located around the globe, leaving large parts of the Earth with deficient spatial coverage. Moreover, clusters of data points show considerable differences in dust deposition despite being close to each other. These inconsistencies are due to relatively large measurement errors in the paleoclimate archives. Specifically, the errors are in the order of 10–20% for ice cores, 50–70% for marine sediments, and 50–80% for loess13.

The data come from paleoclimatic archives10 for the Holocene (top panel) and the LGM (bottom panel).

Since the dust flux measurements are approximately log-normally distributed10, we work with the logarithmic transformation of the data and use a standard normalization based on the z-scores.

Dust fluxes model

The main physical processes we include for atmospheric dust particle transport are the advection along the dominant wind direction and diffusion towards surrounding regions. The most common model is the advection-diffusion equation

where U(x, t) denotes the dust fluxes, v is the wind field, and D is the diffusion coefficient43. Since we only consider static dust fluxes averaged over thousands of years, we use the steady-state advection-diffusion equation

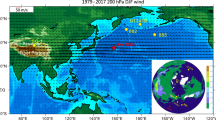

where u(x) denotes the time-averaged dust fluxes. The advection velocity is taken as the average wind speed in zonal direction v = (v1, 0) taken from ERA5 reanalysis data (see Fig. 5), which we used for both Holocene and LGM conditions. Detailed wind information is unavailable for the LGM, as there is no agreement in model simulations, except that the prevailing wind patterns were not fundamentally different from today44,45. Furthermore, we assume the diffusion parameter D to be constant globally.

The wind velocity is in east-west direction at each latitude. The data come from ERA5 reanalysis products54. The average is calculated for the period 2011-2020 and integrated from 1000 to 200 hPa.

We model the Earth’s surface as a sphere and write the advection-diffusion equation in spherical coordinates46. For this purpose, let us denote the longitude by λ ∈ ( − π, π) and the latitude by \(\theta \in (-\frac{\pi }{2},\frac{\pi }{2})\) in radians. Hence,

is the model we use in the PINN’s design, together with conditions at the boundaries of the spherical coordinate system. In the direction of the longitude, we have the periodic boundary conditions

Concerning latitude, we model continuity in the poles by using

where usouth and unorth are prescribed values at the south and north poles, respectively.

Physics-Informed Neural Networks

A PINN is an algorithm based on supervised machine learning that can intrusively combine empirical data with physical information modeled as a PDE. In our case, the input of the PINN is the spatial location on the Earth’s surface, and the output is the dust deposition. During the training process, the PINN optimizes a nonlinear function that fits both data and the PDE model. This optimization process requires specifying a loss function to find optimal parameters for the neural network. Since the PINN uses automatic differentiation to calculate the derivatives of the objective function, we can include our PDE and boundary conditions in the loss function. Figure 6 shows a general workflow of the PINN.

Here, x1 and x2 are the input variables, σ are the parameters of the neural network and u the objective function. Automatic differentiation calculates the derivatives of the objective function, and the data and model fits are combined in a loss function \({{\mathcal{L}}}\). The minimization process through backpropagation gives updated parameters σ⋆.

Loss function design

The objective of a PINN is to fit a function \(\hat{u}({{\bf{x}}})\) to the PDE model and the empirical data. For this purpose, we define a combined loss function

where \({{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{{{\rm{data}}}}\) and \({{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{{{\rm{model}}}}\) are the loss functions corresponding to the data and model, respectively, and w1 and w2 are the respective weights. The data loss function is given by

where \(\tilde{u}\) denotes the observations at the points \({\tilde{x}}_{j}\) for j = 1, …, Ndata with Ndata the number of training items, and \(\hat{u}\) denotes the PINN’s estimation. We always use the standard L2 norm. The model loss function consists of two parts, one for the PDE (\({{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{{{\rm{PDE}}}}\)) and one for the boundary conditions (\({{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{{{\rm{BC}}}}\)), that is,

The PDE loss function quantifies the fit of the PINN’s estimation regarding our model PDE (3) as

where \({\overline{x}}_{j}\) for j = 1…, NPDE are the collocation points in which the PINN evaluates the PDE. Finally, the loss function regarding the boundary conditions (4) and (5) is given by

where \({\overline{\theta }}_{j}\) and \({\overline{\lambda }}_{j}\) for j = 1…, NBC are the collocation points for the boundary conditions. Here, we include the offset ϵ to avoid numerical issues due to singularities in the spherical coordinate system at the poles. Depending on the specific problem setting, the relative emphasis between the data and the model can be adjusted by setting the weights w1 and w2.

Neural network design

We normalize all empirical data with their z-scores in a logarithmic scale and normalize the computational domain to [ − 2, 2] for the longitude and [ − 1, 1] for the latitude to improve the stability of the training algorithm and mitigate vanishing gradient pathologies28. The polar regions are excluded from training to avoid singularities in the model. Specifically, we consider latitudes between − 80 to + 80 degrees and impose a constant solution at these polar boundaries. This choice is a reasonable modeling approach since the excluded zones are ice-covered regions far away from any potential dust source, and the atmospheric circulation patterns are symmetric around the polar high-pressure systems. Hence, excluding the polar regions will not produce noticeable discrepancies in global dust transport.

We use a fully connected neural network with five hidden layers, each containing 32 neurons with a Scaled Exponential Linear Unit (SELU) activation function and Glorot normal initializer. The optimizer is Adam, and the learning rate is set to 10−5. Computational experience of various network designs supports these choices as having sufficient expressiveness while avoiding overfitting our specific empirical dataset. The PINN is trained on the entire dataset to incorporate all information available from the sparse and stratified data. We programmed the PINN using the DeepXDE library47. This open-source Python package provides essential methods such as mesh creation, neural network definitions, initial and boundary conditions, and optimization algorithms.

Model parameters

The PINN evaluates the PDE model loss term (9) in collocation points that can be specified in arbitrary locations. We choose a regular grid with 5 degrees spacing between the points. This resolution is fine enough to capture the dominant advection and diffusion phenomena of the global dust deposition and sufficiently coarse to avoid overfitting. The boundary conditions are evaluated at 5 degrees resolution also.

Regarding the physical parameters in the PDE model (3), the value of v1 is taken from the wind data presented in Fig. 5 and normalized by its maximum value. However, no reliable information on the diffusion coefficient D is available in the literature on measurements or simulations of global dust fluxes. Hence, we opted to use an inverse problem approach in the PINN to infer this parameter from the empirical data48. Using the same approach, we also estimated the values of unorth and usouth. These parameters are necessary for the boundary conditions (5), but no measurement sites are available close to the poles. More specifically, these physical parameters are incorporated as unknown parameters in the neural network, and their values are approximated within the same training process as for the field estimation17. Hence, these physical parameters are optimized to fit the data and the model best.

As part of the design of the PINN, we have to choose the weights of the separate terms in the combined loss function (6). These weights give relative importance between the data and the model in the training process. We normalize the weights by choosing a weight equal to one for the north and south pole boundary conditions. We use one-half each for the periodic boundary conditions since they are in the same location. Then, we set the data loss weight equal to ten to emphasize the importance of closely fitting the empirical data. Setting the model loss weight is arguably the most subjective decision22. Automatic approaches such as adaptive weights and multi-objective optimization have been proposed in the literature49,50,51. However, there is no consensus on setting the weights, and the best choice strongly depends on the application of interest. The common practice is manually setting the weights and evaluating the implications with domain knowledge52. In our case, a large model weight yields too smooth fields, and a small model weight overfits the observations. Supplementary Discussion 5 provides more details. We found a good balance for a weight of w2,1 = 1 for the PDE loss term.

Kriging method

We compare our innovative PINN design with the more conventional kriging method. Kriging is a geostatistical interpolation technique that uses a weighted average of nearby samples53. We use the same kriging interpolation as performed in ref. 10 for the DIRTMAP database. For brevity, we refer to that publication for the algorithmic details and model choices.

Data availability

The paleoclimate measurements of dust deposition rates are available at the World Data Center PANGAEA, dataset 847983, as a supplement to10.

Code availability

The software code is publicly available on GitHub: https://github.com/evantwout/PINN-global-dust.

References

Mahowald, N. Aerosol indirect effect on biogeochemical cycles and climate. Science 334, 794–796 (2011).

Kok, J. F. et al. Mineral dust aerosol impacts on global climate and climate change. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 71–86 (2023).

Shaffer, G. & Lambert, F. In and out of glacial extremes by way of dust-climate feedbacks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 115, 2026–2031 (2018).

Albani, S. et al. Improved dust representation in the Community Atmosphere Model. J. Adv. Modeling Earth Syst. 6, 541–570 (2014).

Ohgaito, R. et al. Effect of high dust amount on surface temperature during the Last Glacial Maximum: a modelling study using MIROC-ESM. Climate 14, 1565–1581 (2018).

Sueyoshi, T. et al. Set-up of the PMIP3 paleoclimate experiments conducted using an Earth system model, MIROC-ESM. Geoscientific Model Dev. 6, 819–836 (2013).

Yukimoto, S. et al. A new global climate model of the Meteorological Research Institute: MRI-CGCM3. Model description and basic performance. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 90, 23–64 (2012).

Hopcroft, P. O. & Valdes, P. J. On the role of dust-climate feedbacks during the mid-Holocene. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 1612–1621 (2019).

Kok, J., Albani, S., Mahowald, N. & Ward, D. An improved dust emission model–Part 2: evaluation in the Community Earth System Model, with implications for the use of dust source functions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 13043–13061 (2014).

Lambert, F. et al. Dust fluxes and iron fertilization in Holocene and Last Glacial Maximum climates. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 6014–6023 (2015).

Kohfeld, K. E. & Harrison, S. P. DIRTMAP: the geological record of dust. Earth-Sci. Rev. 54, 81–114 (2001).

Maher, B. et al. Global connections between aeolian dust, climate and ocean biogeochemistry at the present day and at the last glacial maximum. Earth-Sci. Rev. 99, 61–97 (2010).

Cosentino, N. J. et al. Paleo ± dust: Quantifying uncertainty in paleo-dust deposition across archive types. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 941–959 (2024).

Kageyama, M. et al. The PMIP4 contribution to CMIP6 – Part 4: Scientific objectives and experimental design of the PMIP4-CMIP6 Last Glacial Maximum experiments and PMIP4 sensitivity experiments. Geoscientific Model Dev. 10, 4035–4055 (2017).

Lambert, F. et al. Regional patterns and temporal evolution of ocean iron fertilization and CO2 drawdown during the last glacial termination. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 554, 116675 (2021).

Saini, H. et al. Southern ocean ecosystem response to Last Glacial Maximum boundary conditions. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 36, e2020PA004075 (2021).

Raissi, M., Perdikaris, P. & Karniadakis, G. E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 378, 686–707 (2019).

Karniadakis, G. E. et al. Physics-informed machine learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 422–440 (2021).

Sahli Costabal, F., Yang, Y., Perdikaris, P., Hurtado, D. E. & Kuhl, E. Physics-informed neural networks for cardiac activation mapping. Front. Phys. 8, 42 (2020).

Jagtap, A. D., Kharazmi, E. & Karniadakis, G. E. Conservative physics-informed neural networks on discrete domains for conservation laws: Applications to forward and inverse problems. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 365, 113028 (2020).

Yang, Y. & Perdikaris, P. Adversarial uncertainty quantification in physics-informed neural networks. J. Comput. Phys. 394, 136–152 (2019).

Cuomo, S. et al. Scientific machine learning through physics–informed neural networks: where we are and what’s next. J. Sci. Comput. 92, 88 (2022).

He, Q. & Tartakovsky, A. M. Physics-informed neural network method for forward and backward advection-dispersion equations. Water Resour. Res. 57, e2020WR029479 (2021).

Okazaki, T., Ito, T., Hirahara, K. & Ueda, N. Physics-informed deep learning approach for modeling crustal deformation. Nat. Commun. 13, 7092 (2022).

Penwarden, M., Zhe, S., Narayan, A. & Kirby, R. M. Multifidelity modeling for physics-informed neural networks (PINNs). J. Comput. Phys. 451, 110844 (2022).

Smith, J. D., Ross, Z. E., Azizzadenesheli, K. & Muir, J. B. HypoSVI: Hypocentre inversion with stein variational inference and physics informed neural networks. Geophys. J. Int. 228, 698–710 (2022).

Cai, S. et al. Flow over an espresso cup: inferring 3-D velocity and pressure fields from tomographic background oriented schlieren via physics-informed neural networks. J. Fluid Mech. 915, A102 (2021).

Kissas, G. et al. Machine learning in cardiovascular flows modeling: predicting arterial blood pressure from non-invasive 4D flow MRI data using physics-informed neural networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 358, 112623 (2020).

Linka, K. et al. Bayesian physics informed neural networks for real-world nonlinear dynamical systems. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 402, 115346 (2022).

Tuia, D. et al. Toward a collective agenda on AI for earth science data analysis. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 9, 88–104 (2021).

Rolnick, D. et al. Tackling climate change with machine learning. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 55, 1–96 (2022).

Cosentino, N., Opazo, N., Lambert, F., Osses, A. & van ’t Wout, E. Global-krigger: A global kriging interpolation toolbox with paleoclimatology examples. Geochem., Geophysics, Geosystems 24, e2022GC010821 (2023).

Struve, T. et al. A circumpolar dust conveyor in the glacial southern ocean. Nat. Commun. 11, 5655 (2020).

Swap, R., Garstang, M., Greco, S., Talbot, R. & Kållberg, P. Saharan dust in the Amazon basin. Tellus B 44, 133–149 (1992).

Bristow, C. S., Hudson-Edwards, K. A. & Chappell, A. Fertilizing the Amazon and equatorial Atlantic with West African dust. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37 (2010).

Wang, S., Yu, X. & Perdikaris, P. When and why PINNs fail to train: a neural tangent kernel perspective. J. Comput. Phys. 449, 110768 (2022).

Krishnapriyan, A., Gholami, A., Zhe, S., Kirby, R. & Mahoney, M. W. Characterizing possible failure modes in physics-informed neural networks. In: 35th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2021) (NIPS, 2021).

Gao, H., Zahr, M. J. & Wang, J.-X. Physics-informed graph neural Galerkin networks: A unified framework for solving PDE-governed forward and inverse problems. Computer Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 390, 114502 (2022).

Jiang, P. et al. Digital twin earth–coasts: Developing a fast and physics-informed surrogate model for coastal floods via neural operators. In: Fourth Workshop on Machine Learning and the Physical Sciences (NeurIPS 2021) (2021).

Jin, X., Cai, S., Li, H. & Karniadakis, G. E. NSFnets (Navier-Stokes flow nets): physics-informed neural networks for the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations. J. Comput. Phys. 426, 109951 (2021).

Yang, L., Meng, X. & Karniadakis, G. E. B-PINNs: Bayesian physics-informed neural networks for forward and inverse PDE problems with noisy data. J. Comput. Phys. 425, 109913 (2021).

Kashinath, K. et al. Physics-informed machine learning: case studies for weather and climate modelling. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 379, 20200093 (2021).

Stocker, T. Introduction to Climate Modelling. Advances in Geophysical and Environmental Mechanics and Mathematics (Springer, 2011).

Rojas, M. Sensitivity of southern hemisphere circulation to LGM and 4 × CO2 climates. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 965–970 (2013).

Kageyama, M. et al. The PMIP4 Last Glacial Maximum experiments: preliminary results and comparison with the PMIP3 simulations. Climate 17, 1065–1089 (2021).

Fletcher, S. J. in Semi-Lagrangian Advection Methods and Their Applications in Geoscience Ch. 12 (Elsevier, 2020).

Lu, L., Meng, X., Mao, Z. & Karniadakis, G. E. DeepXDE: A deep learning library for solving differential equations. SIAM Rev. 63, 208–228 (2021).

Tartakovsky, A. M., Marrero, C. O., Perdikaris, P., Tartakovsky, G. D. & Barajas-Solano, D. Physics-informed deep neural networks for learning parameters and constitutive relationships in subsurface flow problems. Water Resour. Res. 56, e2019WR026731 (2020).

Wang, S., Teng, Y. & Perdikaris, P. Understanding and mitigating gradient flow pathologies in physics-informed neural networks. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 43, A3055–A3081 (2021).

de Wolff, T., Lincopi, H. C., Martí, L. & Sanchez-Pi, N. MOPINNs: an evolutionary multi-objective approach to physics-informed neural networks. In Proc. Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion, 228–231 (2022).

van der Meer, R., Oosterlee, C. W. & Borovykh, A. Optimally weighted loss functions for solving PDEs with neural networks. J. Computational Appl. Math. 405, 113887 (2022).

Rasht-Behesht, M., Huber, C., Shukla, K. & Karniadakis, G. E. Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) for wave propagation and full waveform inversions. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 127, e2021JB023120 (2022).

Cressie, N. The origins of kriging. Math. Geol. 22, 239–252 (1990).

Bell, B. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis: Preliminary extension to 1950. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 147, 4186–4227 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.M. designed the methodology, performed the analysis, and prepared the manuscript. F.L, J.S., and E.W. supervised the research and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Franz Kanngießer and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Keiichiro Hara and Carolina Ortiz Guerrero. [A peer review file is available.]

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Molina Catricheo, C.A., Lambert, F., Salomon, J. et al. Modeling global surface dust deposition using physics-informed neural networks. Commun Earth Environ 5, 778 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01942-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01942-2

This article is cited by

-

Global dust impacts on biogeochemical cycles and climate

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2025)