Abstract

Irrigation is a fundamental practice for mitigating crop yield losses from drought and heat extremes. However, the extent to which irrigation moderates crop sensitivity to these stresses and the future quantity of irrigation required to maintain crop yields remain unclear. Here, we use a meta-analysis of maize field experiments across the Ogallala Aquifer to quantify how varying irrigation amounts influence yield sensitivity to heat and drought based on a panel regression model. We find that each 100 mm increase in irrigation reduces heat sensitivity of maize by 7.6%. By the 2050s, offsetting a projected 26% yield decline under a high-emission scenario, primarily driven by intensifying heat stress, would require a 67% increase in irrigation amounts. These findings provide key insights into the interplay between irrigation and climatic extremes, highlighting the urgent need for efficient irrigation strategies to balance crop yield and water resource sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change, characterized by rising temperatures, intensifying droughts, flooding, and increasing heatwaves, poses a threat to agricultural productivity and global food security1,2,3,4. Over the past decade, these climatic extremes have caused estimated losses of $30 billion in global crop production5, highlighting the vulnerability of existing agricultural systems. Projections suggest that future climates will be even hotter and drier6, further exacerbating threats to crop yields7,8. In response, farmers have increasingly adopted adaptive practices to safeguard food production, with irrigation emerging as a long-term, primary option9,10,11. By stabilizing crop water supply and mitigating heat stress, irrigation plays a critical role in sustaining food production, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions highly susceptible to climate change impacts12.

Irrigated agriculture is generally more productive in terms of crop yields than rain-fed agriculture13. However, it also drives immense water demands, accounting for approximately 70% of global freshwater withdrawals14,15. As temperatures rise, farmers may further intensify irrigation to meet the increased water needs of crops, accelerating groundwater depletion and straining water availability16,17,18. One example of how this is occurring is in the U.S. Ogallala Aquifer19,20, one of the world’s largest and most productive aquifers. Spanning 450,660 km² across eight states (Fig. 1)19, the Ogallala Aquifer supports 30% of U.S. crop and livestock production, contributing $1.75 billion to maize production and driving a $35 billion agricultural industry each year18,21. Yet, decades of intensive groundwater extraction for irrigation have caused widespread water-level declines, raising urgent concerns about the sustainability of water resources and agricultural systems in the face of future climate change18,20,22.

Amid the dual pressures of climate change threatening crop yields and accelerating global groundwater depletion23, a nuanced understanding of irrigation’s ability to maintain crop yields in the face of increasing heat and drought stress is vital. A large and growing body of literature has documented the benefits of irrigation in mitigating the effects of climatic extremes on crop yields at regional and national levels9,10,11,24,25,26,27. However, due to the limited availability of data on the amounts of irrigation during the crop growing season across a large regional scale, these studies typically rely on coarse water management information (irrigated vs. rainfed) and concluded that irrigation can offset yield losses caused by adverse climate. For example, Tack et al.28 found that a 1°C temperature increase reduces U.S. wheat yields by 6% under rainfed conditions, while such losses are completely offset under irrigation conditions. More recent studies10,29 have incorporated irrigation area proportions, defined as the fraction of cropped area that is irrigated within each district, to account for the role of irrigation in reducing crop vulnerability to climate extremes.

Despite these efforts, there remains uncertainty in quantifying the specific irrigation amounts (Irr) needed to mitigate crop sensitivity to heat or drought. Better understanding this mitigation effect is crucial for improving climate impact projections and optimizing irrigation management practices for sustainable water use, as well as food security30. These two interacting subjects are our primary study foci: irrigation (underground water savings of the Ogallala Aquifer) and crop production. Most current studies lack long-term observation data on Irr at the regional scale, meaning that the simplified estimates of irrigation used in those studies could introduce uncertainties when assessing the extent to which irrigation can alleviate heat sensitivity28,31. Additionally, the lack of quality irrigation data in previous studies at the regional scale limits their ability to capture the dynamic of actual water supply, leading to uncertain assessments of drought impacts on crop yields32. Recent studies also emphasize the need for further study to better understand irrigation as an adaptation strategy25,28,31, particularly in large-scale studies25,28.

Here, we confront this challenge by performing a meta-analysis of field experiments on irrigated maize across the U.S. Ogallala Aquifer region, which serves as a case study to explore the role of irrigation in enhancing crop resilience to climatic extremes (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). The dataset includes 707 observations from 33 studies with specific Irr (mm) and management practices (see Methods for data selection). Our analysis focused on maize because of its extensive irrigated harvested area and larger water needs than some other economically viable crops in the U.S. Great Plains33. Using this observed dataset, we developed a panel regression model to investigate the relationship between irrigated maize yields, climate variables, and Irr during the growing season. The main objectives of this study are to: (1) quantify the extent to which varying Irr mitigate heat sensitivity and drought impacts; (2) project impacts of future climate change on irrigated maize yields and decompose the contribution of climate drivers; and (3) estimate the additional Irr required to counteract climate change-induced yield losses, which, in turn, will impact groundwater depletion rates.

Results

Irrigated maize yield responses to climate variables

To assess how irrigated maize yields respond to climate variables, we used a linear mixed-effects model that incorporated Irr as a factor, along with nonlinear terms and interactions (Eq. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). Water stress was quantified by defining a water stress index, calculated as the ratio of water supply (precipitation (Prcp) + Irr) to potential evapotranspiration (pET), where a smaller ratio indicates greater insufficiency of water to meet water demand. This approach captures the direct effect of irrigation on maize yield by increasing water supply and alleviating water stress. Our results showed a nonlinear yield response to this ratio, which aligns with the response based on observed data (Fig. 2a,b). By integrating actual Irr alongside Prcp across diverse climatic conditions, our study provides robust empirical evidence of how water supply influences maize yields at a regional scale. Under conditions of water deficits, yields increased rapidly as the ratio rose, whereas with greater water availability, yield gains gradually diminished (Fig. 2b). This saturation effect underscores the importance of optimizing irrigation strategies by integrating Prcp patterns to balance water supply and crop demand, while aligning water management with economic goals to enhance farm profitability and promote sustainable resource use.

a Observed yield categorized into seven bins based on the ratio of water supply to pET. Boxplots indicate the median (white line), the mean (black dots), and 25–75th percentiles (box) and 5–95th percentiles (whiskers). b Simulated yield response to the ratio of water supply to pET, estimated using a linear-mixed effects model. c Sensitivity of yield to EDD as a function of irrigation amount, illustrated through the interaction term between EDD and irrigation amount. The histogram shows the distribution of irrigation amounts sampled. In (b) and (c), the solid black line represents the average effect, with the shaded area indicating the 2.5–97.5th percentile ranges based on 1000 bootstrapped samples.

To estimate how irrigation modulates yield sensitivity to extreme heat, we included an interaction term between extreme degree days (EDD) (EDD; °C days), defined as accumulation of degree days above 30 °C34,35, and Irr in the model (Eq. 1). The estimated yield sensitivity to EDD \(\left(\frac{\partial {Yield}}{\partial {EDD}}\right)\) depends on Irr and can be expressed as \(\frac{\partial {Yield}}{\partial {EDD}}={\beta }_{2}+{\beta }_{6}{Irr}\), where \({\beta }_{2}\) and \({\beta }_{6}\) represent the coefficients for EDD and Irr × EDD, respectively (see Methods). A positive \({\beta }_{6}\) indicates that irrigation alleviates the heat impact, and vice versa. Our analysis showed a negative, statistically significant coefficient for EDD (−0.041 t ha−1 per [°C days]; p value < 0.05), indicating a negative effect of heat stress on maize yield. However, the positive, statistically significant coefficient for the interaction term between Irr and EDD (0.0031 ha−1 per [100 mm °C days]; p value < 0.05) suggests that increasing irrigation mitigates this negative impact of heat stress on maize yield (Supplementary Table 2). Importantly, we revealed the dynamic role of irrigation in mitigating yield sensitivity to heat stress. Without irrigation (Irr = 0 mm), a unit increase in EDD was associated with an average yield decline of 0.041 t ha−1 (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 2). Increasing Irr mitigated this sensitivity, with each additional 100 mm of irrigation reducing the yield sensitivity to EDD by 7.6% on average (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 2).

Projected climate-driven changes in irrigated maize yield

We assessed the impact of climate change on irrigated maize yield by the 2050s (2050–2059) under four shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs) (SSP126, SSP245, SSP370, and SSP585) relative to the historical period (2010–2019) (see Methods). To establish a baseline, we first estimated the irrigation amounts required to achieve the current irrigated maize yields (Supplementary Fig. 1) across various grid cells of the Ogallala Aquifer. We quantified irrigation demands of 339 mm on average (ranging from 50 to 550 mm; Fig. 3a), with the larger values observed in the southern regions due to lower growing-season Prcp and greater evapotranspiration rates compared to those in the northern regions (Supplementary Fig. 2). We also calculated state-level average irrigation amounts and compared these estimates with observed state-level data from the USDA-NASS Census of Irrigation, which provides crop-specific irrigation information. Results showed a similar spatial pattern between observed and estimated irrigation amounts (correlation equals to 0.93), with an average absolute difference across states being 30 mm (Supplementary Fig. 3), reinforcing the reliability of our estimates. These baseline irrigation levels were used to predict yield changes under future’s climates.

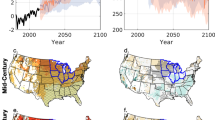

a Estimated averaged current irrigation amount during the 2010s. b Projected climate-induced yield changes relative to current yields based on two assumptions: fixed growing degree days (GDD) at current levels (gray) and fixed phenology at current levels (red). Yield impacts were calculated as the ensemble mean of seven climate models, weighted by gridded harvested areas. Box plot indicated median (white line), 25–75th percentiles (box), 5–95th percentiles (whiskers), and mean value (black dot). c,d, Spatial distribution of projected relative yield change under both assumptions.

To project the potential impacts of climate change on maize yields, we developed two assumptions regarding farmer responses: (1) “fixed GDD,” where farmers continue to use maize hybrids with current growing degree day (GDD) requirements; and (2) “fixed phenology,” where farmers attempt to maintain current phenology by selecting hybrids with larger GDD requirements (Methods and Supplementary Fig. 4). Note that, both assumptions maintain constant planting dates based on local historical averages. Under the “fixed GDD,” average maize yields are projected to decline by 20% under the low-warming scenario (SSP126) and by up to 32% under the greatest warming scenario (SSP585) (Fig. 3b). Spatially, yield losses are most severe in northeastern regions of the Ogallala Aquifer, reaching up to 50%, while southwestern regions exhibit smaller yield losses, generally below 20% (Fig. 3c). Although the “fixed phenology” assumption alleviates yield losses by an average of 6% (Fig. 3b), climate change-induced yield declines persist, ranging from 14% under SSP126 to 26% under SSP585 (Fig. 3b). The larger yield losses under the “fixed GDD” assumption are primarily attributed to accelerated crop development under higher temperature, which allows hybrids to meet GDD requirements in fewer days36,37. This shortens the effective duration of growing season by 5–35 days from south to north (Supplementary Fig. 5a), reducing accumulated radiation and, consequently, yields. Given the ongoing depletion of water resources in this region, we also simulated yield changes under the “fixed phenology” assumption with future irrigation amounts limited to 75% of the local historical levels. The results indicated that yield losses increase by an additional 10% (Supplementary Fig. 6), highlighting the dual challenges of water scarcity and climate change for sustaining maize yields.

Decomposing climate drivers under the “fixed phenology” assumption

Given that maintaining current phenology by selecting greater-GDD hybrids results in smaller yield losses compared to maintaining current GDD hybrids, we focused our subsequent analyses under “fixed phenology” assumption. We decomposed the future yield variability attributed to changes in specific climate variables (Methods). Our results suggest that warmer temperatures have dual, counteracting effects on yields, even when hybrids with greater GDD requirements are used. On the one hand, the ensemble mean shows that an increase in GDD under SSP126 and SSP585 would theoretically work to have a positive effect on yields of 9% and 13%, respectively (Fig. 4a). In addition, greater surface solar radiation (SSR) under all future climate scenarios would contribute an average of 5% to yield gains. However, these yield benefits will be counteracted by two main factors: (1) increased extreme heat stress (EDD), resulting in yield declines of 19 and 31% for SSP126 and SSP585, respectively; and (2) increased water stress associated with increased temperature and evapotranspiration rates, which would reduce yields by 9 and 13% for SSP126 and SSP585, respectively. Taken together, future climate changes are projected to result in average yield losses of 14 and 26% for SSP126 and SSP585, respectively (Fig. 3b), with heat stress identified as the dominant driver (Fig. 4a). The counteracting effects of increased temperature on maize yields differ spatially within the Ogallala Aquifer. For example, under SSP585, in the northern regions, particularly Nebraska, the positive effect on yields from the increase in GDD are more pronounced than in the southern regions (Fig. 4b–e). However, the northern regions will also face severe yield losses from increased water stress (~15%; Fig. 4e) and heat stress (~40%; Fig. 4c). Similar spatial patterns in the decomposition of climate drivers for other scenarios are also presented in Supplementary Fig. 7.

a Yield change was attributed to specific climate change factors, including changes in growing degree days (ΔGDD), extreme degree days (ΔEDD), solar radiation (ΔSSR), and the ratio of precipitation to potential evapotranspiration (ΔRatio of Prcp to pET). The climate change-induced yield changes were calculated as the ensemble mean of seven climate models, weighted by gridded harvested areas. Box plot indicated median (black line), 25–75th percentiles (box), 5–95th percentiles (whiskers), and mean value (circle). b–e, Spatial distribution of climate drivers contributing to yield changes under the SSP585 scenario.

Future irrigation requirements to offset maize yield losses under the “fixed phenology” assumption

We assessed the additional irrigation required by the 2050s to fully offset climate change-induced yield losses. We first estimated future irrigation requirements to maintain current maize yield levels, and then calculated the difference from current irrigation needs. Results indicated that the spatial pattern of projected future irrigation (Supplementary Fig. 8) is similar to the current irrigation pattern (Fig. 3a). We projected that under high-emission scenario (SSP585), the average irrigation amounts by the 2050s will be 567 mm (ranging from 300 to 700 mm; Supplementary Fig. 8), which is 67% larger than the current average. Specifically, the ensemble means of additional irrigation required to offset climate-induced yield loss (Fig. 3d) are 131, 154, 202, and 228 mm under SSP126, SSP245, SSP370, and SSP585, respectively (Fig. 5a), with northeastern regions requiring up to an additional 350 mm under high-emission scenarios (Fig. 5b) due to greater yield declines (Fig. 3d).

a The additional irrigation amount needed to compensate for yield losses due to climate change was calculated as the ensemble mean of seven climate models, with the error bars showing the 2.5–97.5th percentiles. Values were weighted by gridded harvested areas. b Spatial distribution of the additional irrigation requirements for each climate scenarios.

Discussion

Despite the recognized potential of irrigation to alleviate the impacts of heat and water stresses in crops10,28,38, the extent to which varying irrigation amounts modulate these impacts remains uncertain. Quantifying this relationship is essential for assessing the risk of yield reductions in irrigated crops due to future climate change, especially as water resources become more limited and deficit irrigation, applying less water than full crop-water requirements, may become more likely as a viable adaptation strategy39. The Ogallala Aquifer region, where maize production heavily depends on irrigation due to inadequate annual Prcp (ranging from 500 mm in the east to 200 mm in the west; Supplementary Fig. 2), serves as an ideal natural laboratory for investigating the role of irrigation in sustaining yields. This study employed a panel regression model that integrates dynamic irrigation effects to assess future climate-driven changes in maize yield and irrigation requirements.

Recent research has shown that conversion from center pivot irrigation to subsurface irrigation can reduce maize irrigation requirements while maintaining yields40,41. Although our analysis did not specifically focus on irrigation methods, most irrigation systems included in the meta-analysis utilized sprinkler irrigation, such as center pivot systems, which is the most widely used in the US42,43 and generally more efficient than surface (furrow) irrigation44. Additionally, due to data limitations regarding specific irrigation amounts during different growth stages, our analysis was constrained to total irrigation amounts throughout the growing season (from planting to maturity). However, these irrigation amounts may be distributed unevenly during the growing season, affecting irrigation efficiency39. Thus, improving data on irrigation timing would help to further refine our understanding of how irrigation will influence yield resilience under future climate change scenarios. Despite these limitations, our study provides additional perspective to previous studies on the role of irrigation in mitigating climate impacts.

Theoretically, future maize phenological dates could shift due to changes in climate conditions and management practices. However, in this study, we fixed future planting and maturity dates based on local historical averages. Our primary goal was to evaluate the impact of future climate change on maize yield under historical irrigation levels. To achieve this, we controlled future phenological windows to align with historical benchmarks, providing a practical reference point. This approach allowed us to assess the influences of future climate on maize yield in comparison to historical climate conditions within the same phenological window, consistent with the approach used in previous studies45,46. Thus, we did not consider the potential advancement of planting dates, which may increase the risk of exposing maize to early spring frosts, adding uncertainty to our projections. For comparison, we also conducted a “fixed GDD” scenario, assuming that future maize hybrids will maintain the same GDD requirements as current hybrids, implying no adaptation to climate change. Without adaptation, crops may experience accelerated maturation and shortened growth durations due to rising temperature, leading to larger yield losses. Future studies could explore optimal adaptation strategies that combine crop variety selection28 and phenological adjustments47 under irrigation to further minimize yield effects.

In summary, our results indicated that irrigation amount plays a critical role in adjusting maize yield responses to water and heat stress. We found each additional 100 mm of irrigation reduced yield sensitivity to heat stress by an average of 7.6%, emphasizing the importance of effective irrigation strategies in enhancing resilience to climate warming. Additionally, many field and experimental site studies have observed the nonlinear yield response to water supply; they typically focus on local conditions. In contrast, our study quantified this relationship at a regional scale, integrating climate and water supply variations to provide actionable insights for optimizing irrigation practices more broadly. By identifying the saturation effect of yield gains, we offer a framework for determining optimal irrigation thresholds tailored to different Prcp zones. This is crucial for improving water use efficiency and developing adaptive irrigation strategies that account for regional climatic variability, ultimately supporting sustainable water resource management in water-limited crop production regions. Furthermore, we integrated these relationships into projections of future climate impacts on irrigated maize yields and irrigation demand. Projections indicated that, without changes in irrigation levels, maize yields could decline by 20% on average by the 2050s across four climate scenarios, primarily due to increased heat stress. To fully offset these potential losses, an estimated 228 mm of additional irrigation would be necessary under the high-emission scenario (SSP585), implying the challenges of balancing food demand with sustainable water use under a warming climate. While irrigation can help mitigate heat sensitivity in crop yields, the substantial water demand required to offset potential yield declines under future climate scenarios highlights the need for more integrated and efficient strategies. These strategies include targeted irrigation during critical crop growth stages to reduce water use, integrating the relationships between irrigation amounts and climate impacts (heat and drought) into crop models48,49,50 to optimize irrigation management, and aligning irrigation practices with broader climate adaptation and water management policies. Additionally, as water availability is likely expected to decrease in arid and semi-arid regions, a combination of efficient irrigation, crop diversification, and the use of drought- and heat-tolerant hybrids will be crucial for enhancing resilience and ensuring long-term sustainability.

Furthermore, the results of this study contribute to the debate about whether the production of maize for grain should be a priority use of Ogallala Aquifer water, particularly in the central and southern areas of the aquifer in Kansas and Texas, where evapotranspiration rates are larger and Prcp is smaller. In these areas, forage production is a priority to support a burgeoning dairy industry and the already large cattle feeding industry. However, maize grain can be brought into the region from the Midwest economically on unit trains, whereas forages for beef and dairy production must be produced more locally due to the cost of transportation. Also, forage growing and irrigation seasons are both shorter, and irrigation demands are smaller than those necessary for maize grain production. Given the declining aquifer, which means that increased irrigation is not a realistic adaptation to climate change without severe reductions in area devoted to maize grain, conversion of maize grain areas to forage production is likely.

Methods

Literature search

A comprehensive search for peer-reviewed publications on the effect of irrigation on maize yield in the U.S. was conducted using Google Scholar and Web of Science. Search terms included ‘‘corn,’’ ‘‘maize,’’ ‘‘deficit (or limited) irrigation,’’ and ‘‘water use.’’ Publications were screened based on the following criteria: (1) studies focusing on field-based maize conducted in the Ogallala Aquifer states (Fig. 1) during the period of 1986–2020, and (2) studies providing data on planting and harvest (or maturity) dates, plant population density (plants ha-1), nitrogen application rate (kg ha−1), maize yield (t ha−1; adjusted to 15.5% standardized moisture content), and irrigation amounts (mm) during the growing season. This screening process identified 33 relevant publications, yielding 707 observations across 87 site-years (Fig. 1). The complete reference list of publications is given in Supplementary Table 1.

Climate data

To characterize historical weather conditions, we extracted daily maximum temperature (Tx) and minimum temperature (Tn), and Prcp from the Global Historical Climatology Network-daily51. Daily SSR data were obtained from the Prediction of Worldwide Energy Resources, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA/POWER). Additionally, daily pET was taken from the gridded meteorological dataset52. We then interpolated climatic data with a Delaunay Triangulation53 to field sites to approximate the daily weather experienced by the crop.

Estimating effects of irrigation on maize yield

We developed a linear mixed-effects model to quantify the influence of climate variables on maize yield, with a focus on how irrigation mitigates heat and water stress. All climate variables were calculated over the maize growing season (from planting to maturity). For cases where maturity dates were unavailable, we estimated maturity dates as four weeks prior to the reported harvest date54. The model is specified as:

where Yl,t,i (t ha−1) is maize yield for site l, year t, and observation i. αt represents the random intercept effect for years, commonly used to control the influence of unobserved factors, such as advancements of maize hybrids over time. αt is estimated using a categorical variable for years. GDD (°C days) denotes GDD between 8 and 30 °C, and EDD (°C days) represents EDD above 30 °C34,35, both calculated using hourly temperature simulated from Tx and Tn55. SSR (MJ m−2) is accumulated solar radiation.

To characterize water stress, we calculated the ratio of \(\frac{{Prcp}+{Irr}}{{pET}}\), where Prcp (mm) is the accumulated precipitation, Irr (mm) is the accumulated irrigation amounts, and pET (mm) is the accumulated pET during the maize growing season. We included the interaction term (Irr × EDD) in our model, allowing us to quantify the moderating effects of irrigation on yield sensitivity to EDD as \(\frac{\partial Y}{\partial {EDD}}={\beta }_{2}+{\beta }_{6}{Irr}\). Note that we interpreted the effect of the interaction term (Irr × EDD) with respect to EDD, as our objective is to quantify how irrigation mitigates the impact of heat stress on crop yields, rather than how heat stress influences the efficiency of irrigation. We also tested the statistical significance of this interaction term using a simulated likelihood ratio test56, suggesting that incorporating this term significantly (p value < 0.05) enhanced the model’s performance compared to the model that excluded it. All variance inflation factors values for climate predictors are below 7, confirming that multicollinearity is not a concern in our model.

To capture the effects of main management practices on maize yield, we included nitrogen application rate (N) and plant population density (Pop) in the model. We used quadratic terms of these two variables to account for the potential nonlinear influence on yields57,58. To capture site-specific soil influences, we directly incorporated key soil properties rather than using site-fixed effects, which can restrict predictions to known sites. Specifically, we used layer-weighted averages for soil texture (sand and silt proportions) in the top 100 cm of soil, derived from the nearest 30-m grid cell in the POLARIS soil dataset59. This dataset, developed based on the Soil Survey Geographic Database (SSURGO) and the State Soil Geographic Database (STASGO2), provides high-resolution soil characteristics that effectively represent local conditions. As the sum of sand, silt, and clay proportions equals to 1, we only included the proportion of sand and silt in the model to prevent multicollinearity. By including soil texture, the model captures important site-level variation, allowing for broader spatial predictions across various regions.

Additionally, the β terms represent the set of coefficients associated with climatic variables influencing maize yields. Specifically, β1 and β2 capture the nonlinear effects of temperature on yields (unit: t ha−1 [°C days]−1); β3 quantifies the effect of SSR on yields (unit: t ha−1 [MJ m−2]−1); β4 and β5 indicate the nonlinear effects of water conditions on yields (unit: t ha−1 [mm mm−1]−1); β6 represents the effect of irrigation in alleviating heat stress (unit: t ha−1 [mm °C days]−1). γ represents the coefficients of management practices (γ1 to γ4) and soil characteristics (γ5 and γ6). Specifically, γ1 and γ2 capture the potential nonlinear effects of N on yields (unit: t ha−1 [kg N ha−1]−1); γ3 and γ4 represent the potential nonlinear effects of plant population density on yields (unit: t ha−1 [plants ha−1]−1); γ5 and γ6 describe the effects of soil sand and clay content, respectively (unit: t ha−1 percentage−1).

Projected climate-driven changes in irrigated maize yield

We projected climate change-driven yield changes for irrigated maize in the Ogallala Aquifer region, focusing on grid cells with harvested areas more than 300 hectares (Fig. 1)60. The average climate condition during the 2010s (2010–2019, excluding 2012 due to severe drought and low yields61) was used as a current climate baseline. To estimate irrigation needs to achieve current maize yields in farmers’ fields, we used three additional datasets during the 2010s: (1) state-level phenology (planting and maturity dates) estimated62,63 based on the US Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service (USDA-NASS) (Supplementary Fig. 4); (2) management practices (N fertilizer and plant population density) for irrigated maize field trials from online publicized state’s Maize Performance Test Reports (Supplementary Table 3); and (3) agricultural district-level irrigated maize yield data from USDA-NASS (Supplementary Fig. 1), which offered broader spatial coverage than county-level yield data. These data typically represent current management practices and maize yield levels in the Ogallala Aquifer region.

To estimate the average irrigation amounts required to achieve the observed average yields (Supplementary Fig. 1) under current management practices across the Ogallala Aquifer (Fig. 3a), we first interpolated the 2010s climate data to the grid cells and calculated the climate variables during the growing season based on the state-level phenology. We then calculated the average N fertilizer rate (234 kg ha−1) and plant population density (75,191 plants ha−1) based on the public dataset of management practices in irrigated maize fields across our study domain during the 2010s (Supplementary Table 3). These management values, characterizing current farmers’ practices, were incorporated into our panel regression model (Eq. 1) to estimate irrigation amounts under historical climate conditions. These baseline irrigation estimates were then used to project climate change-driven yield variation for the 2050s (2050−2059) relative to the 2010s. Projections were conducted for four SSPs (SSPs: SSP126, SSP245, SSP370, and SSP585) using climate data from seven global climate models (GCMs; Supplementary Table 4) provided by the NASA Earth Exchange Global Daily Downscaled Projections (NEX-GDDP-CMIP6)64. This dataset provides bias-corrected and downscaled climate change projections suitable for evaluating climate change impacts.

To project climate-driven yield changes, we considered two scenarios: (1) fixing future GDD at the 2010s levels, while recalculating future phenology (Supplementary Fig. 5a), and (2) holding phenology fixed at the 2010s levels, while allowing GDD to vary (Supplementary Fig. 5b). The ‘‘fixed phenology’’ scenario maintains phenological windows consistent with historical benchmarks. This approach allows us to isolate the effects of future climate change by removing the influences of shifts in phenological timing, enabling a direct comparison of future climate impacts against historical conditions. This assumes that farmers could adapt to climate warming by selecting hybrids with longer GDD requirements to maintain the historical length of the growing season. In contrast, the ‘‘fixed GDD’’ scenario assumes that farmers continue to use current hybrids with the same GDD requirements, representing a non-adaptative baseline. This estimation captures the direct effects of climate change on crop yield and its indirect effect through changes in the length of growing season.

To assess the impacts of climate change on maize yield, we first projected irrigated maize yields for the 2050s under four SSP scenarios using our fitted regression models (Eq. 1). To isolate the effects of climate change, we used future climate variables in the models while management practices (irrigation amounts, N fertilizer rate, and plant population density) were held constant at historical average levels (2010–2019). We then calculated the yield changes relative to the historical average yield. We further quantified the contributions of changes in specific climate variables between the 2050s and the 2010s to yield changes (ΔY) using our model (f):

Here, Climate1 and Climate2 refer to the sets of climate variables used in our model (Eq. 1), averaged over the 2010s and 2050s, respectively. For each grid, the ΔY is explained by the changes in four climate components:

where the subscripts “1” and “2” denote the averages for the reference period (the 2010s) and the future period (the 2050s), respectively.

Data availability

The data sources for the meta-analysis are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Other data sources used in this study are provided in Supplementary Tables 3 and 5. The data used to display main figures are shown at https://figshare.com/s/52b0c22495a43dc6d175.

Code availability

The code used to generate main figures in this study is available through a public repository at https://figshare.com/s/52b0c22495a43dc6d175.

References

Trnka, M. et al. Adverse weather conditions for European wheat production will become more frequent with climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 637–643 (2014).

Challinor, A. J., Koehler, A.-K., Ramirez-Villegas, J., Whitfield, S. & Das, B. Current warming will reduce yields unless maize breeding and seed systems adapt immediately. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 954–958 (2016).

Zhang, L. et al. An unprecedented fall drought drives Dust Bowl–like losses associated with La Niña events in US wheat production. Sci. Adv. 10, eado6864 (2024).

Lesk, C., Rowhani, P. & Ramankutty, N. Influence of extreme weather disasters on global crop production. Nature 529, 84–87 (2016).

Gupta, A., Rico-Medina, A. & Caño-Delgado, A. I. The physiology of plant responses to drought. Science 368, 266–269 (2020).

Dai, A. Increasing drought under global warming in observations and models. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 52–58 (2012).

McKenzie, F. C. & Williams, J. Sustainable food production: constraints, challenges and choices by 2050. Food Secur.7, 221–233 (2015).

Qi, W., Feng, L., Yang, H. & Liu, J. Increasing concurrent drought probability in global main crop production countries. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, 97060 (2022).

Mueller, N. D. et al. Closing yield gaps through nutrient and water management. Nature 490, 254–257 (2012).

Zaveri, E. & Lobell, B. D. The role of irrigation in changing wheat yields and heat sensitivity in India. Nat. Commun. 10, 4144 (2019).

Troy, T. J., Kipgen, C. & Pal, I. The impact of climate extremes and irrigation on US crop yields. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 054013 (2015).

Siebert, S., Ewert, F., Rezaei, E. E., Kage, H. & Graß, R. Impact of heat stress on crop yield—on the importance of considering canopy temperature. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 044012 (2014).

Fischer, G., Tubiello, F. N., Van Velthuizen, H. & Wiberg, D. A. Climate change impacts on irrigation water requirements: effects of mitigation, 1990–2080. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 74, 1083–1107 (2007).

Pimentel, D. et al. Water resources: agricultural and environmental issues. Bioscience 54, 909–918 (2004).

McDermid, S. et al. Irrigation in the Earth system. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 435–453 (2023).

Bhattarai, N. et al. Warming temperatures exacerbate groundwater depletion rates in India. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi1401 (2023).

Bhargava, A. Climate variability, rice production and groundwater depletion in India. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 034022 (2018).

Orduña Alegría, M. E. et al. Unlocking aquifer sustainability through irrigator-driven groundwater conservation. Nat. Sustain. 7, 1574–1583 (2024).

Cano, A. et al. Current knowledge and future research directions to link soil health and water conservation in the Ogallala aquifer region. Geoderma 328, 109–118 (2018).

Mieno, T., Foster, T., Kakimoto, S. & Brozović, N. Aquifer depletion exacerbates agricultural drought losses in the US high plains. Nat. Water 2, 41–51 (2024).

Basso, B., Kendall, A. D. & Hyndman, D. W. The future of agriculture over the Ogallala Aquifer: Solutions to grow crops more efficiently with limited water. Earth’s. Future 1, 39–41 (2013).

Haacker, E. M., Kendall, A. D. & Hyndman, D. W. Water level declines in the high plains aquifer: predevelopment to resource senescence. Ground Water 54, 231–242 (2016).

Aeschbach-Hertig, W. & Gleeson, T. Regional strategies for the accelerating global problem of groundwater depletion. Nat. Geosci. 5, 853–861 (2012).

Zhu, P. et al. Warming reduces global agricultural production by decreasing cropping frequency and yields. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 1016–1023 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Quantifying irrigation cooling benefits to maize yield in the US midwest. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 3065–3078 (2020).

Li, X. & Troy, T. Changes in rainfed and irrigated crop yield response to climate in the western US. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 064031 (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Global irrigation contribution to wheat and maize yield. Nat. Commun. 12, 1235 (2021).

Tack, J., Barkley, A. & Hendricks, N. Irrigation offsets wheat yield reductions from warming temperatures. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 114027 (2017).

Birthal, P. S., Hazrana, J., Negi, D. S. & Pandey, G. Benefits of irrigation against heat stress in agriculture: evidence from wheat crop in India. Agric. Water Manag. 255, 106950 (2021).

West, P. C. et al. Leverage points for improving global food security and the environment. Science 345, 325–328 (2014).

Taraz, V. Can farmers adapt to higher temperatures? Evidence from India. World Dev. 112, 205–219 (2018).

Li, J. & Lei, H. Impacts of climate change on winter wheat and summer maize dual-cropping system in the North China plain. Environ. Res. Commun. 4, 075014 (2022).

Kukal, M. S. Consumptive water use and efficiency of irrigated US corn: learning from hundreds of site-management-year observations. Water Resour. Res. 60, e2024WR037434 (2024).

Lobell, D. B., Deines, J. M. & Tommaso, S. D. Changes in the drought sensitivity of US maize yields. Nat. Food 1, 729–735 (2020).

Zhu, P. & Burney, J. Untangling irrigation effects on maize water and heat stress alleviation using satellite data. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 26, 827–840 (2022).

Zhang, T., Huang, Y. & Yang, X. Climate warming over the past three decades has shortened rice growth duration in China and cultivar shifts have further accelerated the process for late rice. Glob. Change Biol. 19, 563–570 (2013).

Lizaso, J. et al. Impact of high temperatures in maize: phenology and yield components. Field Crops Res. 216, 129–140 (2018).

Luan, X., Bommarco, R., Scaini, A. & Vico, G. Combined heat and drought suppress rainfed maize and soybean yields and modify irrigation benefits in the USA. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 064023 (2021).

Comas, L. H., Trout, T. J., DeJonge, K. C., Zhang, H. & Gleason, S. M. Water productivity under strategic growth stage-based deficit irrigation in maize. Agric. Water Manag. 212, 433–440 (2019).

Evett, S. R., Marek, G. W., Colaizzi, P. D., Brauer, D. K. & O’Shaughnessy, S. A. Corn and sorghum ET, E, yield, and CWP as affected by irrigation application method: SDI versus mid-elevation spray irrigation. Trans. ASABE 62, 1377–1393 (2019).

Evett, S. R., Marek, G. W., Colaizzi, P. D., Brauer, D. & Howell, T. A. Are crop coefficients for SDI different from those for sprinkler irrigation application? Trans. ASABE 63, 1233–1242 (2020).

Yan, L. & Roy, D. P. Conterminous United States crop field size quantification from multi-temporal landsat data. Remote Sens. Environ. 172, 67–86 (2016).

Evett, S. R. et al. Past, present, and future of irrigation on the US great plains. Trans. ASABE 63, 703–729 (2020).

Irmak, S., Mohammed, A. T. & Kukal, M. S. Maize response to coupled irrigation and nitrogen fertilization under center pivot, subsurface drip and surface (furrow) irrigation: Growth, development and productivity. Agric. Water Manag. 263, 107457 (2022).

Schlenker, W. & Roberts, M. J. Nonlinear temperature effects indicate severe damages to US crop yields under climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Usa. 106, 15594–15598 (2009).

Lobell, D. B. et al. Greater sensitivity to drought accompanies maize yield increase in the US midwest. Science 344, 516–519 (2014).

Anapalli, S. S., Ma, L., Nielsen, D., Vigil, M. & Ahuja, L. Simulating planting date effects on corn production using RZWQM and CERES-maize models. Agron. J. 97, 58–71 (2005).

Zhang, J. et al. Sustainable irrigation based on co-regulation of soil water supply and atmospheric evaporative demand. Nat. Commun. 12, 5549 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Joint modeling of crop and irrigation in the central United States using the Noah-MP land surface model. J. Adv. Model Earth Syst. 12, e2020MS002159 (2020).

Partridge, T. et al. Irrigation benefits outweigh costs in more US croplands by mid-century. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 274 (2023).

Menne, M. J., Durre, I., Vose, R. S., Gleason, B. E. & Houston, T. G. An overview of the global historical climatology network-daily database. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 29, 897–910 (2012).

Abatzoglou, J. T. Development of gridded surface meteorological data for ecological applications and modelling. Int. J. Climatol. 33, 121–131 (2013).

Barber, C. B., Dobkin, D. P. & Huhdanpaa, H. The quickhull algorithm for convex hulls. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 22, 469–483 (1996).

Tollenaar, M., Fridgen, J., Tyagi, P., Stackhouse, P. W. Jr & Kumudini, S. The contribution of solar brightening to the US maize yield trend. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 275–278 (2017).

Cesaraccio, C., Spano, D., Duce, P. & Snyder, R. L. An improved model for determining degree-day values from daily temperature data. Int. J. Biometeorol. 45, 161–169 (2001).

Hox, J., Moerbeek, M. & Van de Schoot, R. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. (Routledge, 2017).

van Grinsven, H. J. et al. Establishing long-term nitrogen response of global cereals to assess sustainable fertilizer rates. Nat. Food 3, 122–132 (2022).

Novacek, M. J., Mason, S. C., Galusha, T. D. & Yaseen, M. Bt transgenes minimally influence maize grain yields and lodging across plant populations. Maydica 59, 90–95 (2014).

Chaney, N. W. et al. POLARIS soil properties: 30-m probabilistic maps of soil properties over the contiguous United States. Water Resour. Res. 55, 2916–2938 (2019).

Grogan, D., Frolking, S., Wisser, D., Prusevich, A. & Glidden, S. Global gridded crop harvested area, production, yield, and monthly physical area data circa 2015. Sci. Data 9, 15 (2022).

Boyer, J. et al. The US drought of 2012 in perspective: a call to action. Glob. Food Secur. 2, 139–143 (2013).

Zhao, H. et al. Nonlinear contributions of surface solar brightening to maize yield gains in the US corn belt. Agric. Meteorol. 356, 110169 (2024).

Sacks, W. J. & Kucharik, C. J. Crop management and phenology trends in the US corn belt: impacts on yields, evapotranspiration and energy balance. Agric. Meteorol. 151, 882–894 (2011).

Thrasher, B. et al. NASA global daily downscaled projections, CMIP6. Sci. Data 9, 262 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation projects (2345039 and 2420405) (X.L) and USDA Agricultural Research Service (A22-0103-001) (X.L). Contribution no. 25-138-J is from the Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L., G.B., and L.Z. designed and coordinated the research, conducted the analysis, and wrote the initial manuscript draft. L.Z. and H.Z. collected all the data needed. S.R.E. and X.L. contributed to discussing the methodology and the results. S.R.E., P.D.C., Q.X., G.M., R.D., H.Z., and N.W. interpreted the results, advised on presentation of the main findings, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Zewei Ma, Mahmoud Suliman and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Aliénor Lavergne. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Bai, G., Evett, S.R. et al. Increased irrigation could mitigate future warming-induced maize yield losses in the Ogallala Aquifer. Commun Earth Environ 6, 483 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02459-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02459-y