Abstract

Samples from the carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu and CI (Ivuna-type) chondrites are dominated by low-temperature, aqueously formed secondary minerals, with rare occurrences of anhydrous primary minerals that formed in the high-temperature region of the solar protoplanetary disk. Here, we show that small (<a few tens of micrometers) Ca-Al-rich inclusions (CAIs) in Ryugu and Ivuna formed within ~0.2 Ma of the Solar System’s birth. These CAIs exhibit mineralogical, O-isotopic, and chronological similarities to CAIs in ordinary and other carbonaceous chondrites, indicating their ubiquitous presence across chondrites. In contrast, larger (>submillimeter) CAIs, commonly found in other carbonaceous chondrites and thought to have been retained via pressure bump(s) in the disk, are absent in Ryugu and CI chondrites. This absence implies that their parent planetesimals formed at a greater heliocentric distance, beyond the influence of a pressure bump created by proto-Jupiter, accreting only small CAIs that evaded radial drift toward the Sun.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Samples collected from the carbonaceous asteroid (162173) Ryugu by the JAXA Hayabusa2 spacecraft exhibit chemical and petrographic similarities to CI (Ivuna-type) carbonaceous chondrites1,2,3,4 as well as to samples from the carbonaceous asteroid (101955) Bennu5. Extensive aqueous alteration on the parent planetesimals of Ryugu and CI chondrites led to the predominance of secondary phases in their mineralogy, which formed through interaction with aqueous fluids1,2,3,4,6. Anhydrous primary minerals, such as olivine, low-Ca pyroxene, spinel, and hibonite, are rare and occur predominantly as small (<~30 µm) isolated mineral fragments embedded in a phyllosilicate matrix2,3,7,8,9,10,11. Refractory inclusions, including Ca-Al-rich inclusions (CAIs) and amoeboid olivine aggregates (AOAs), which formed either by condensation from the solar nebular gas or by the remelting of condensate precursor solids12, have been identified in Ryugu samples3,11 and the Ivuna CI chondrite8,13. These inclusions formed in a high-temperature region14, most likely in the innermost part of the solar protoplanetary disk15, before being transported to colder outer regions, where the parent planetesimals of Ryugu and CI chondrites accreted along with CO2-bearing ice3,6,8,11,16,17.

Understanding the genetic relationship of CAIs among chondrites is crucial for constraining the accretion environments of their parent planetesimals, as the distribution and size variations of CAIs reflect dust transport, retention, and mixing processes in the solar protoplanetary disk18. CAIs in carbonaceous chondrites (e.g., CV [Vigarano-type], CK [Karoonda-type], CO [Ornans-type], CM [Mighei-type], and CR [Renazzo-type]) typically exhibit a broad size distribution, ranging from micrometers to approximately one centimeter12,19, and are recognized as the earliest solids formed within a few hundred thousand years after the birth of the Solar System20,21,22,23,24. In contrast, only small CAIs or their fragments (<a few tens of micrometers) have been identified in Ryugu and CI chondrites3,8,11,13, and their genetic relationship to CAIs in other carbonaceous chondrite groups remains ambiguous, primarily due to the lack of formation age determinations.

The 26Al–26Mg systematics, based on the decay of short-lived 26Al to 26Mg with a half-life of 0.705 Ma (ref. 25), provides a high-precision chronometer for CAIs and has been applied to those in ordinary chondrites26,27 and carbonaceous chondrites other than CI21,22,23,24. While a melilite-rich CAI was previously identified in Ivuna, the absence of detectable radiogenic 26Mg precluded its precise age determination13. Similarly, CAIs found in Ryugu samples were inferred to have formed during the earliest stages of Solar System evolution based on similarities of the mineral chemistry and O-isotope compositions to CAI in carbonaceous chondrites11, but no chronological constraints have been reported. Further complicating this picture, CAI-like particles in comet 81 P/Wild2 samples exhibit distinct mineral chemistry compared to those in carbonaceous chondrites28 and lack detectable radiogenic 26Mg (refs. 29,30). Given these complexities, determining the formation ages of CAIs in Ryugu and CI chondrites is essential for constraining their genetic relationship to other CAI populations. Here, we report the formation ages of CAIs composed of hibonite and spinel found in Ryugu and the Ivuna CI chondrite, determined by the 26Al–26Mg systematics. We also measured the Al–Mg isotope compositions of olivine in an AOA from Ivuna8 and AOA-like, 16O-rich isolated olivine grains from Ryugu to constrain the Mg-isotope composition of the solar nebular gas from which they condensed.

Results

Mineralogy and petrology

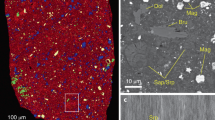

We identified a CAI composed of hibonite and spinel with a maximum dimension of ~24 µm, designated as RC06, in a polished section of the Ryugu C0006 particle (Fig. 1a–e). RC06 is embedded in the phyllosilicate matrix of a less-altered clast, where anhydrous primary minerals such as olivine and low-Ca pyroxene are abundant. The clast is enriched in S and Fe and depleted in Mg and Si compared to the major lithologies and carbonates are almost exclusively calcite, consistent with less-altered clasts observed in other Ryugu particles3,8. RC06 appears to be an aggregate composed of micrometer-sized hibonite and spinel grains, with a tiny perovskite grain embedded within hibonite. In the polished section, RC06 appears as two inclusions separated by ~5 µm; however, their mineralogical similarity and irregular shapes suggests that they likely originated from a single CAI. Magnetite plaquettes enclosed within spinel and hibonite grains indicate that RC06 was incorporated into the Ryugu’s parent planetesimal before the onset of aqueous alteration, during which magnetite precipitated. We also identified an angular CAI composed of hibonite and spinel, designated as HKI02, in a polished section of Ivuna (Fig. 1f, g). HKI02 occurs in the major lithology of Ivuna, similar to HKI01, a subrounded AOA found from Ivuna8. HKI02 is an inclusion composed of hibonite and spinel, with a maximum dimension of ~19 µm. The mineralogical textures of RC06 and HKI02 resemble those of hibonite-spinel CAIs found in carbonaceous chondrites31,32.

a BSE image of primary mineral-rich clast of the Ryugu C0006 particle. The yellow box indicates the area shown in (d). b Combined X-ray elemental map of the same area shown in (a) using Mg Kα, Ca Kα, and Al Kα lines assigned for RGB color channels. c Combined X-ray elemental map of (a) using Fe Kα, S Kα, and O Kα lines assigned for RGB color channels. d BSE image of a hibonite-spinel CAI in Ryugu C0006. e Combined X-ray elemental map of (d) using Mg Kα, Ca Kα, and Al Kα lines assigned for RGB color channels. f BSE image of a hibonite-spinel CAI in Ivuna. g Combined X-ray elemental map of (f) using Mg Kα, Ca Kα, and Al Kα lines assigned for RGB color channels. Cal calcite, Dol dolomite, Hib hibonite, Mgt magnetite, Ol olivine, Po pyrrhotite, Pv perovskite, Sp spinel.

The chemical compositions of hibonite and spinel in RC06 and HKI02 are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The FeO contents of spinel grains in RC06 and HKI02 are ~1 wt% and their Cr2O3 contents are ~0.4 and ~0.1 wt%, respectively. Hibonite grains exhibit a charge-balanced substitution of Mg2+ + Ti4+ = 2Al3+. These mineral chemistries are consistent with those of CAIs from carbonaceous and ordinary chondrites27,31,32,33, as well as Ivuna13 and Ryugu samples11.

The HKI01 AOA from Ivuna is composed of olivine, diopside, anorthite, and spinel grains8. Olivine grains are nearly pure forsterite (Mg/[Mg + Fe] × 100, Mg# of ~99). Isolated olivine grains, ranging in size from ~16 to 20 µm, were also identified in the polished section of Ryugu C0006. These grains are highly Mg-rich (Mg# ~99, Supplementary Table 1), similar to the majority of isolated olivine grains in Ryugu2,3,8,9. The CaO contents of these olivine grains are less than 0.1 wt%, and their MnO/FeO ratios range from 1.6 to 6.1.

Oxygen-isotope compositions and 26Al–26Mg systematics

The O-isotope compositions of hibonite and spinel in the Ryugu and Ivuna CAIs, as well as those of the isolated olivine grains from Ryugu, are listed in Supplementary Table 2. In an oxygen three-isotope diagram (δ17O versus δ18O, where δiO = [(iO/16O)sample/(iO/16O)SMOW – 1] × 1000, i = 17 or 18, and SMOW is standard mean ocean water), the isotopic compositions plot on the carbonaceous chondrite anhydrous mineral (CCAM) line34 or the primitive chondrule mineral (PCM) line35 (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. 2). All these minerals are 16O-rich. The hibonite and spinel in the CAIs exhibit Δ17O values, deviation from the terrestrial mass-dependent fractionation law (δ17O – 0.52 × δ18O), of –24.8 ± 0.6‰ (2 standard deviations, 2 SD, n = 4), and the isolated olivine grains from Ryugu exhibit Δ17O values of –23.8 ± 1.5‰ (n = 6).

Data are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Errors correspond to 2σ. TF terrestrial fractionation line, CCAM carbonaceous chondrite anhydrous mineral line, PCM primitive chondrule mineral line, Hib hibonite, Sp spinel.

The Al–Mg isotope compositions of hibonite in RC06 and HKI02, olivine in HKI01, and the isolated olivine grains from Ryugu are listed in Supplementary Table 3. All hibonite data exhibit excess radiogenic 26Mg, as indicated by δ26Mg* values (deviation from a mass-dependent fractionation line; see Methods) beyond analytical uncertainties (Fig. 3). The HKI01 olivine and the 16O-rich isolated olivine grains from Ryugu exhibit constant δ26Mg* values of 0.02 ± 0.06‰ (n = 5).

Data are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Al-Mg isotope compositions of 16O-rich olivines were also used for defining isochrons (see text for details). Isoplot-R Model 1 was used to fit the isochron. Errors correspond to 2σ. Hib hibonite, Ol olivine.

Discussion

The constituent minerals of RC06 and HKI02, hibonite and spinel, are predicted to be high-temperature condensates from a solar-composition gas, based on the thermodynamic calculations14. Their condensation temperatures are estimated to be >~1400 K at a total pressure of 10−3 atm and >~1300 K at 10−5 atm. The 16O-rich compositions of hibonite and spinel in these CAIs (Δ17O = –24.8 ± 0.6‰) are consistent with those of pristine minerals in CAIs from other carbonaceous chondrites19,22 and the unequilibrated ordinary chondrite Semarkona36. These observations indicate that the CAIs formed by direct condensation from a 16O-rich nebular gas. Similarly, the Cr2O3 contents of spinel grains in these CAIs (<0.4 wt%) are comparable to those in carbonaceous chondrites31,32, Semarkona33, Ivuna13, and the Ryugu samples11, but differ significantly from spinel in CAI-like particles from comet 81 P/Wild2, which exhibit Cr2O3 contents of ~1.9–3.9 wt% (ref. 28). This compositional disparity suggests that RC06 and HKI02 experienced thermal histories distinct from those of CAI-like particles in comet 81 P/Wild2, consistent with inferences drawn from CAIs in other Ryugu particles11.

The Δ17O values of –23.8 ± 1.5‰ and the mineral chemistry (e.g., Mg#, CaO contents, and MnO/FeO ratios) of the 16O-rich isolated olivine grains in Ryugu are consistent with those of olivine in the HKI01 AOA from Ivuna8, as well as with 16O-rich isolated olivine grains in Ryugu and Ivuna2,8,11 and AOAs in other carbonaceous chondrite groups22,37,38. As discussed by ref. 8, these grains are genetically linked to AOAs and are therefore most likely direct condensates from a 16O-rich nebular gas.

The δ26Mg* values of the HKI01 olivine and the 16O-rich olivine grains in Ryugu (0.02 ± 0.06‰) are indistinguishable from the Solar System bulk initial δ26Mg* of –0.040 ± 0.029‰ (ref. 39) or –0.0159 ± 0.0014‰ (ref. 40), as inferred from the bulk Al–Mg isochrons of CAIs and AOAs in CV chondrites. Given that the hibonite data exhibit no significant variations in 27Al/24Mg ratios, we define the Al–Mg isochrons of the RC06 and HKI02 CAIs using the Al–Mg isotope compositions of these olivines, together with those of the hibonite in the CAIs (Fig. 3). The resulting isochrons for RC06 and HKI02 yield initial 26Al/27Al ratios, (26Al/27Al)0, of (5.1 ± 0.6) × 10−5 and (4.2 ± 0.7) × 10−5, respectively. Notably, incorporating the Al–Mg isotope compositions of bulk Ryugu particles41 or bulk CI chondrites40 into the isochron calculations does not significantly affect the (26Al/27Al)0 values, given the much larger analytical uncertainties of the δ26Mg* values of the hibonite. The inferred (26Al/27Al)0 for RC06 is identical to the canonical value of ~5.2 × 10−5 (refs. 39,40), whereas HKI02 exhibits a slightly lower, sub-canonical value. These values are consistent with those reported for CAIs in carbonaceous chondrites, which range from ~5.2 × 10−5 to ~3.4 × 10−5 (refs. 21,22,23), those in ordinary chondrites26,27, and chemically separated, monomineralic corundum grains from the Orgueil CI chondrite42. However, they differ markedly from CAI-like particles in comet 81 P/Wild2, which exhibit no detectable excess 26Mg (refs. 29,30). This distinction further supports the interpretation that the CAIs in Ryugu and Ivuna experienced formation histories distinct from those of CAI-like particles in comet 81 P/Wild2.

The well-defined bulk Al–Mg isochrons of CAIs suggest that 26Al was once homogeneously distributed in the CAI-forming region at the canonical level39,40. Assuming such a homogeneous distribution, the formation ages of RC06 and HKI02 are estimated to be 0.03 (+0.14/−0.12) Ma and 0.22 (+0.20/−0.17) Ma after the formation of canonical CAIs, respectively. However, various meteoritic records imply that 26Al may have been heterogeneously distributed in the CAI-forming region, likely during the earliest stages of the solar protoplanetary disk, before complete homogenization of 26Al (refs. 19,40,42). Even if RC06 and HKI02 formed before the complete homogenization of 26Al, their formation still occurred during the earliest stages of Solar System evolution. Therefore, our data indicate that the RC06 and HKI02 CAIs from Ryugu and Ivuna formed in a high-temperature region of the earliest Solar System, within ~0.2 Ma after the formation of canonical CAIs. These findings demonstrate that the small CAIs in Ryugu and Ivuna are mineralogically, isotopically, and chronologically similar to CAIs in carbonaceous and ordinary chondrites, suggesting their ubiquitous presence across chondrites and indicating that they share some of the same building blocks. Such small CAIs, which originated in the high-temperature region of the solar protoplanetary disk, must have been transported across the disk and retained in the accretion regions of parent planetesimals of ordinary and carbonaceous chondrites, including Ryugu and CI chondrites.

No CAIs larger than the submillimeter scale have been identified in the Ryugu samples and CI chondrites in either the present study or previous literature1,2,3,4,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, whereas submillimeter- to centimeter-sized CAIs are commonly found in other carbonaceous chondrite groups12,19. Similar observations apply to the related AOAs. We interpret this difference in CAI size as evidence of size-dependent dust migration. During the evolution of the protoplanetary disk, after mass accretion from the parent molecular cloud core ceased within a few hundred thousand years, millimeter-sized dust particles experienced aerodynamic drag from the disk gas, causing them to drift radially toward the Sun18,43. The drift timescale τ for a dust particle of radius a, assuming the minimum mass solar nebula model, is estimated as: τ ~ 105 × (a/1 mm)–1 yr (ref. 44). This relationship implies that only small CAIs, with sizes of <~100 μm, could have remained in the disk without significant radial drift for over a million years after disk formation, persisting until the accretion of the parent planetesimals of chondrites that could have occurred later than ~1 Ma after CAI formation45. Therefore, the ubiquitous presence of small (<a few tens of micrometers) CAIs in chondrites, including CI and ordinary chondrites as well as Ryugu samples, can be readily explained within this framework. By contrast, the retention of larger (>submillimeter) CAIs in the other carbonaceous chondrite groups must have been facilitated by additional mechanism(s).

Recent observations of protoplanetary disks have revealed that millimeter- to centimeter-sized dust particles can be locally concentrated within certain regions of the disk46. One proposed mechanism for generating such substructures is the formation of gas pressure bumps, which act as barriers that trap large dust particles at local pressure maxima, thereby inhibiting their radial drift toward protostars47. The formation of (proto)planets induces such pressure bumps and leads to the accumulation of large dust particles outside their orbits48,49,50. A pressure bump induced by proto-Jupiter has been proposed to create a CAI-enriched region, accounting for the presence of submillimeter- to centimeter-sized CAIs in carbonaceous chondrites other than CI51. The absence of large CAIs in Ryugu and CI chondrites therefore implies that their parent planetesimals either formed prior to the formation of proto-Jupiter or at a greater heliocentric distance beyond the influence of its pressure bump. This interpretation is consistent with the chemically unfractionated features of Ryugu and CI chondrites4. Proto-Jupiter is inferred to have formed within ~1 Ma after CAI formation, based on the isotope dichotomy and Hf–W model ages of iron meteorites49, which predates the formation of parent planetesimals of most chondrites, including Ryugu and CI chondrites3,45. Thus, it is more plausible that the parent planetesimals of Ryugu and CI chondrites formed at a greater heliocentric distance from proto-Jupiter, rather than before its formation.

The distinct accretion region inferred for Ryugu and CI chondrites, based on the distribution and size variations of CAIs, is further supported by their unique nucleosynthetic heritage16 and the near absence of chondrules8. We argue that the parent planetesimals of Ryugu and CI chondrites formed at a greater heliocentric distance from proto-Jupiter, accreting only small CAIs that evaded radial drift toward the Sun and were retained in the outer solar protoplanetary disk. These findings underscore the need to further explore the diversity of planetesimal formation processes and offer important insights into the formation of planets in the outer Solar System and in extrasolar protoplanetary disks.

Methods

Sample preparation and electron microscopy

We prepared two polished sections (C0006-1 and C0006-2) using the Ryugu C0006 particle allocated by the third Announcement of Opportunity (AO) for Ryugu samples from ISAS/JAXA. The C0006 is a particle from the second touchdown sample weighed 16.3 mg and ~4.5 mm in size. First, the whole particle was embedded in epoxy resin (Buhler EpoxiCure 2) and cut into two pieces using diamond blade saw (Musashino Denshi MPC-130). The two pieces were individually embedded in 1-inch epoxy disks and polished with an automatic polishing machine (Musashino Denshi MA-200e). The sample polishing procedures are similar to those by refs. 4,8. Diamond slurries with polycrystalline diamond particles of ~3 µm and ~1 µm dissolved in ethylene glycol and polishing plates composed of copper and tin-antimony alloy were used for polishing. Only >99.5% ethanol was used for cleaning during and after the polishing. Until the RC06 CAI was found on a polished surface using a field emission type scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM; JEOL JSM-7000F) at Hokkaido University, the sections were polished a few times using ~1 µm diamond slurry sprayed on a polishing cloth. The polished section of the Ivuna CI chondrite (Ivuna HK-1; ref. 4) was re-polished with the same procedure until the HKI02 CAI was found.

The polished sections of Ryugu and Ivuna were coated with a thin (~20 nm) carbon film for electron microscopy. Backscattered electron (BSE) images were obtained using the FE-SEM instrument. X-ray elemental mapping and quantitative analysis of chemical compositions were conducted using an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS; Oxford X-Max 150) installed on the FE-SEM. A 15 keV electron beam probe with currents of ~2 nA and ~1 nA were used for the mapping and quantitative analysis, respectively. Quantitative calculations were conducted using Oxford AZtec software. BSE images and pseudo color images made by X-ray elemental mapping were used to determine petrological and mineralogical characteristics of the samples. After electron microscopy was completed, the sections were recoated with an additional thin (~70 nm) gold film using a high-resolution sputter coater (Cressington 208HR) for SIMS measurements.

Oxygen isotope analysis

O-isotope compositions in hibonite, spinel, and olivine from the Ryugu and Ivuna samples were measured with Cameca ims-1280HR SIMS instrument at Hokkaido University. The analytical conditions follow those described in ref. 8. A 133Cs+ primary beam accelerated to 20 keV was employed in the experiment. A normal-incidence electron flood gun was used for electrostatic charge compensation of the analyzing areas during the measurements. Negative secondary ions (16O−, 17O−, and 18O−) were measured simultaneously in the multicollection mode. The mass resolution of M/ΔM for 17O− was set at >6000 to resolve 17O– from 16OH–, while that for 16O− and 18O− was ~2000. The automatic centering program (DTFA and magnetic field) was applied before data collection. Russian spinel (δ18O = 8.5‰) and San Carlos olivine (Mg# = 89; δ18O = 5.2‰) were used as standards to correct the instrumental mass fractionation for hibonite and spinel and olivine, respectively.

For the measurements of hibonite and spinel, an ~3-pA primary beam with an elliptical shape of 0.7 × 1.5 µm (~1.0 × 2.1 µm including beam halo) was used. 16O−, 17O−, and 18O− were measured using a multicollector FC (1011 Ω, designated as L1), an axial EM, and a multicollector EM (designated as H2), respectively. The secondary ion intensities of 16O− were ~2 × 106 cps. The data were collected for 200 cycles with 4 seconds integration time per cycle. The 16OH− count rate was measured immediately after the measurements, and we made tail corrections on 17O−, which were ~0.2–0.3‰. The external reproducibly of the standard measurements (2 SD, n = 20), which was larger than the internal error (2 standard error, 2SE of the cycle data) of samples, was reported as the analytical uncertainties.

For the measurements of olivine, an ~30-pA primary beam with an elliptical shape of 1.5 × 2.5 μm (~2.1 × 3.5 µm including beam halo) was used. Detector settings are the same with those for the ~3-pA condition above. The data were collected for 60 cycles with 4 seconds integration time per cycle. The 16OH− count rate was measured immediately after the measurements, but we did not make a tail correction on 17O− because its contribution to 17O− was calculated as typically ~0.05‰, comparable to that for standards. The reported uncertainties were the larger of the external reproducibility of standard measurements (2 SD) or internal error (2SE of cycle data) of samples.

Al–Mg isotope analysis

Mg-isotope compositions and 27Al/24Mg ratios for the hibonite and olivine from the Ryugu and Ivuna samples were measured using the same SIMS instrument used for the O-isotope analysis. The analytical conditions follow those described in refs. 23,24. A 16O2− primary beam accelerated to 23 keV was employed. For the measurements of hibonite, an ~4-pA primary beam with an elliptical shape of 0.9 × 1.7 μm (~1.3 × 2.1 µm including beam halo) was used. Mg-isotopes (24Mg+, 25Mg+, and 26Mg+) were measured using an axial electron multiplier (EM), while 27Al+ was measured simultaneously with 25Mg+ using a multicollector Faraday cup (FC) (1011 Ω, designed for H2*) in the peak-jumping mode. A waiting time of 2 s was set before counting 27Al+ intensities to compensate the time constants of the FC. The mass resolution of M/ΔM was set at ~4000, which is sufficient to resolve ion interferences (e.g., 48Ca2+, 24MgH+, 25MgH+, and 52Cr2+). The secondary ion intensities of 24Mg+ were ~2.2–2.6 × 104 cps. Each measurement was conducted for 100 cycles, with a counting sequence of 24Mg+ for 2 s, 25Mg+ for 6 s, 27Al+ for 4 s (simultaneously with 25Mg+), and 26Mg+ for 6 s. The obtained count rates were corrected for the FC background and EM deadtime. A synthetic hibonite standard (Hib30) with δ25MgDSM3 = –1.69 ± 0.13‰ (ref. 24) was used as standards to correct the relative sensitivity factor (RSF) of 27Al/24Mg and instrumental mass fractionation. The mass-dependent fractionation of Mg-isotopes are shown as DSM-3 scale52. The external reproducibility of standard measurements (2 SD), internal error (2SE of cycle data), and the uncertainties of reference δ25MgDSM3 and 27Al/24Mg were propagated to obtain the reported uncertainties of δ25MgDSM3 and 27Al/24Mg, because the internal errors are much smaller than the external reproducibility. The δ26Mg* values were calculated using an exponential fractionation law with coefficient αnatural = 0.5128 and as δ26Mg* = δ26Mgsample – [(1 + δ25Mgsample/1000)1/α – 1] × 1000 (ref. 53). The reported uncertainties for the δ26Mg* were assigned as internal errors (2SE).

For the measurements of olivine, an ~0.5-nA primary beam with an elliptical shape of 4 × 6 μm (~5 × 8 µm including beam halo) was used. Mg-isotopes (24Mg+, 25Mg+, and 26Mg+) and 27Al+ were measured simultaneously in the multicollection mode with four Faraday cups: 24Mg+ for L2* (1011 Ω), 25Mg+ for L1 (1012 Ω), 26Mg+ for H1 (1012 Ω), and 27Al+ for H2* (1010 Ω). The mass resolution of M/ΔM was set at ~2000. The contributions of ion interferences (e.g., 48Ca2+, 24MgH+, 25MgH+, and 52Cr2+) were negligible under these conditions. The secondary ion intensities of 24Mg+ were ~1.5 × 108 cps. Each measurement was conducted over 20 cycles, with a counting time of 10 s per cycle, following a 200 s waiting time to compensate for the time constant of the FCs. Obtained count rates were corrected for FC background and relative yield of each detector. The RSF of 27Al/24Mg, defined as (27Al/24MgSIMS)/(27Al/24Mgreal), for olivine was assumed to be 1, because a possible systematic uncertainty in the 27Al/24Mg of the unknown olivines is negligible due to their low ratios (<~0.001). The δ25MgDSM3 values for the unknown olivines were not determined because the mass dependent fractionation for Mg-rich olivine (Mg# > ~80) strongly depends on chemical compositions54 and the use of a single standard is not appropriate. The δ26Mg* values were calculated with the same equation as the hibonite and corrected using San Carlos olivine standard. The external reproducibility of standard measurements (2 SD) and internal error (2SE of cycle data) were propagated to obtain the reported uncertainties in δ26Mg*.

Areas for the O- and Al–Mg isotope analyses were precisely determined according to scanning ion image of 16O−, 24Mg+, or 25Mg+ collected by electron multipliers (axial for 16O− and 24Mg+ and C for 25Mg+) with a procedure similar to that described in ref. 8. Before measurements, we made few sputtered craters near measurement targets using an ~3-pA or ~30-pA, 133Cs+ primary beam by the SIMS and then electron images were obtained by the FE-SEM to obtain distances from the sputtered craters to the measurement targets. The craters were visible in 16O−, 24Mg+, or 25Mg+ scanning images and used to locate the target minerals. Measurement spots were observed by the FE-SEM after SIMS measurements.

Data availability

The datasets used for this study are publicly available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29287775.

References

Ito, M. et al. A pristine record of outer Solar System materials from asteroid Ryugu’s returned sample. Nat. Astron. 6, 1163–1171 (2022).

Nakamura, E. et al. On the origin and evolution of the asteroid Ryugu: a comprehensive geochemical perspective. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B 98, 227–282 (2022).

Nakamura, T. et al. Formation and evolution of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu: Direct evidence from returned samples. Science 379, eabn8671 (2023).

Yokoyama, T. et al. Samples returned from the asteroid Ryugu are similar to Ivuna-type carbonaceous meteorites. Science 379, eabn7850 (2023).

Lauretta, D. S. et al. Asteroid (101955) Bennu in the laboratory: Properties of the sample collected by OSIRIS-REx. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 59, 2453–2486 (2024).

Matsumoto, T. et al. Sodium carbonates on Ryugu as evidence of highly saline water in the outer Solar System. Nat. Astron. 8, 1536–1543 (2024).

Alfing, J., Patzek, M. & Bischoff, A. Modal abundances of coarse-grained (>5μm) components within CI-chondrites and their individual clasts – Mixing of various lithologies on the CI parent body(ies). Geochemistry 79, 125532 (2019).

Kawasaki, N. et al. Oxygen isotopes of anhydrous primary minerals show kinship between asteroid Ryugu and comet 81P/Wild 2. Sci. Adv. 8, eade2067 (2022).

Liu, M.-C. et al. Incorporation of 16O-rich anhydrous silicates in the protolith of highly hydrated asteroid Ryugu. Nat. Astron. 6, 1172–1177 (2022).

Morin, G. L. F., Marrocchi, Y., Villeneuve, J. & Jacquet, E. 16O-rich anhydrous silicates in CI chondrites: implications for the nature and dynamics of dust in the solar accretion disk. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 332, 203–219 (2022).

Nakashima, D. et al. Chondrule-like objects and Ca-Al-rich inclusions in Ryugu may potentially be the oldest Solar System materials. Nat. Commun. 14, 532 (2023).

MacPherson, G. J. in Meteorites and cosmochemical processes: treatise on geochemistry, 2nd edn (eds Holland, H. D. & Turekian, K. K.) 139–179 (Elsevier, Oxford, 2014).

Frank, D. R., Huss, G. R., Zolensky, M. E., Nagashima, K. & Le, L. Calcium-aluminum-rich inclusion found in the Ivuna CI chondrite: Are CI chondrites a good proxy for the bulk composition of the solar system?. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 58, 1495–1511 (2023).

Yoneda, S. & Grossman, L. Condensation of CaO-MgO-Al2O3-SiO2 liquids from cosmic gases. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 59, 3413–3444 (1995).

McKeegan, K. D., Chaussidon, M. & Robert, F. Incorporation of short-lived 10Be in a calcium–aluminum-rich inclusion from the Allende meteorite. Science 289, 1334–1337 (2000).

Hopp, T. et al. Ryugu’s nucleosynthetic heritage from the outskirts of the Solar System. Sci. Adv. 8, add8141 (2022).

Fujiya, W. et al. Carbonate record of temporal change in oxygen fugacity and gaseous species in asteroid Ryugu. Nat. Geosci. 16, 675–682 (2023).

Yang, L. & Ciesla, F. J. The effects of disk building on the distributions of refractory materials in the solar nebula. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 47, 99–119 (2012).

Krot, A. N. Chondrites and their components: records of early solar system processes. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 54, 1647–1691 (2019).

Connelly, J. N. et al. The absolute chronology and thermal processing of solids in the solar protoplanetary disk. Science 338, 651–655 (2012).

MacPherson, G. J., Kita, N. T., Ushikubo, T., Bullock, E. S. & Davis, A. M. Well-resolved variations in the formation ages for Ca–Al-rich inclusions in the early Solar System. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 331–332, 43–54 (2012).

Ushikubo, T., Tenner, T. J., Hiyagon, H. & Kita, N. T. A long duration of the 16O-rich reservoir in the solar nebula, as recorded in fine-grained refractory inclusions from the least metamorphosed carbonaceous chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 201, 103–122 (2017).

Kawasaki, N., Wada, S., Park, C., Sakamoto, N. & Yurimoto, H. Variations in initial 26Al/27Al ratios among fine-grained Ca-Al-rich inclusions from reduced CV chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 279, 1–15 (2020).

Kawasaki, N. et al. 26Al–26Mg chronology of high-temperature condensate hibonite in a fine-grained, Ca-Al-rich inclusion from reduced CV chondrite. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 59, 630–639 (2024).

Norris, T. L., Gancarz, A. J., Rokop, D. J. & Thomas, K. W. Half-life of 26Al. J. Geophys. Res. 88, B331–B333 (1983).

Russell, S. S., Srinivasan, G., Huss, G. R., Wasserburg, G. J. & MacPherson, G. J. Evidence for widespread 26Al in the Solar Nebula and constraints for Nebula time scales. Science 273, 757–762 (1996).

Huss, G. R., MacPherson, G. J., Wasserburg, G. J., Russell, S. S. & Srinivasan, G. Aluminum-26 in calcium-aluminum-rich inclusions and chondrules from unequilibrated ordinary chondrites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 36, 975–997 (2001).

Joswiak, D. J., Brownlee, D. E., Nguyen, A. N. & Messenger, S. Refractory materials in comet samples. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 52, 1612–1648 (2017).

Matzel, J. E. P. et al. Constraints on the formation age of cometary material from the NASA Stardust mission. Science 328, 483–486 (2010).

Ishii, H. A. et al. Lack of evidence for in situ decay of aluminum-26 in comet 81P/Wild 2 CAI-like refractory particles Inti’ and ‘Coki’. In 41st Lunar and Planetary Science Conference XLI, 2317 (abstr.) (ADS, 2010).

Han, J., Brearley, A. J. & Keller, L. P. Microstructural evidence for a disequilibrium condensation origin for hibonite-spinel inclusions in the ALHA77307 CO3.0 chondrite. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 50, 2121–2136 (2015).

Wada, S., Kawasaki, N., Park, C. & Yurimoto, H. Melilite condensed from an 16O-poor gaseous reservoir: evidence from a fine-grained Ca-Al-rich inclusion of Northwest Africa 8613. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 288, 161–175 (2020).

Bischoff, A. & Keil, K. Al-rich objects in ordinary chondrites: related origin of carbonaceous and ordinary chondrites and their constituents. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 48, 693–709 (1984).

Clayton, R. N., Onuma, N., Grossman, L. & Mayeda, T. K. Distribution of the pre-solar component in Allende and other carbonaceous chondrites. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 34, 209–224 (1977).

Ushikubo, T., Kimura, M., Kita, N. T. & Valley, J. W. Primordial oxygen isotope reservoirs of the solar nebula recorded in chondrules in Acfer 094 carbonaceous chondrite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 90, 242–264 (2012).

McKeegan, K. D., Leshin, L. A., Russell, S. S. & MacPherson, G. J. Oxygen isotopic abundances in calcium-aluminum-rich inclusions from ordinary chondrites: implications for nebular heterogeneity. Science 280, 414–418 (1998).

Komatsu, M., Fagan, T. J., Mikouchi, T., Petaev, M. I. & Zolensky, M. E. LIME silicates in amoeboid olivine aggregates in carbonaceous chondrites: indicator of nebular and asteroidal processes. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 50, 1271–1294 (2015).

Fukuda, K. et al. Correlated isotopic and chemical evidence for condensation origins of olivine in comet 81P/Wild2 and in AOAs from CV and CO chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 293, 544–574 (2021).

Jacobsen, B. et al. 26Al–26Mg and 207Pb–206Pb systematics of Allende CAIs: canonical solar initial 26Al/27Al ratio reinstated. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 272, 353–364 (2008).

Larsen, K. K. et al. Evidence for magnesium isotope heterogeneity in the solar protoplanetary disk. Astrophys. J. Lett. 735, L37 (2011).

Bizzarro, M. et al. The magnesium isotope composition of samples returned from asteroid Ryugu. Astrophys. J. Lett. 958, L25 (2023).

Makide, K. et al. Heterogeneous distribution of 26Al at the birth of the Solar System. Astrophys. J. Lett. 733, L31 (2011).

Appelgren, J., Lambrechts, M. & Johansen, A. Dust clearing by radial drift in evolving protoplanetary discs. Astron. Astrophys. 638, A156 (2020).

Weidenschilling, S. J. Aerodynamics of solid bodies in the solar nebula. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 180, 57–70 (1977).

Neumann, W., Ma, N., Bouvier, A. & Trieloff, M. Recurrent planetesimal formation in an outer part of the early solar system. Sci. Rep. 14, 14017 (2024).

Andrews, S. M. et al. The disk substructures at high angular resolution project (DSHARP). I. Motivation, sample, calibration, and overview. Astrophys. J. Lett. 869, L41 (2018).

Haghighipour, N. & Boss, A. P. On gas drag-induced rapid migration of solids in a nonuniform solar Nebula. Astrophys. J. 598, 1301–1311 (2003).

Lambrechts, M., Johansen, A. & Morbidelli, A. Separating gas-giant and ice-giant planets by halting pebble accretion. Astron. Astrophys. 572, A35 (2014).

Kruijer, T. S., Burkhardt, C., Budde, G. & Kleine, T. Age of Jupiter inferred from the distinct genetics and formation times of meteorites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 6712–6716 (2017).

Spitzer, F. et al. The Ni isotopic composition of Ryugu reveals a common accretion region for carbonaceous chondrites. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp2426 (2024).

Desch, S. J., Kalyaan, A. & Alexander, C. M. O’D. The effect of Jupiter’s formation on the distribution of refractory elements and inclusions in meteorites. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 238, 11 (2018).

Galy, A. et al. Magnesium isotope heterogeneity of the isotopic standard SRM980 and new reference materials for magnesium-isotope-ratio measurements. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 18, 1352–1356 (2003).

Davis, A. M. et al. Isotopic mass fractionation laws for magnesium and their effects on 26Al–26Mg systematics in solar system materials. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 158, 245–261 (2015).

Fukuda, K. et al. Magnesium isotope analysis of olivine and pyroxene by SIMS: evaluation of matrix effects. Chem. Geol. 540, 119482 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of the Hayabusa2 project for their technical and scientific contributions. We are grateful to T. Obase for permission to use a diamond blade saw, N. T. Kita for helpful advice on Al–Mg isotope measurements using SIMS, and T. Matsumoto and K. Bajo for constructive discussions. This research was supported in part by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI grants 22K18722, 24KK0072, and 25H00678 (to N.K.), and JGC-Saneyoshi Scholarship Foundation (N.K.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.K. designed the research. N.K. and Y.M. performed SEM observations, conducted SIMS analyses, and interpreted the data. N.S. assisted with SIMS analyses. D.Y. prepared standards for SIMS analyses. S.R and H.Y. supervised the project. N.K. and S.A. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Alexander Krot and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Ke Zhu, Joe Aslin, Alireza Bahadori and Martina Grecequet. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kawasaki, N., Arakawa, S., Miyamoto, Y. et al. Solar System’s earliest solids as tracers of the accretion region of Ryugu and Ivuna-type carbonaceous chondrites. Commun Earth Environ 6, 537 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02511-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02511-x