Abstract

Submarine springs that drain inland karst aquifers may be subject to abrupt flow reversals in which alternatively freshwater outflows to the sea or saltwater inflows into the aquifer. Here we provide a full flow reversal long-duration data time series at the Vise spring (below Thau lagoon, south of France) during which saltwater inflows into the aquifer. We demonstrate that the driving parameter of the hydrosystem regime shifts is the hydraulic gradient between the aquifer and the lagoon, controlled by water density changes. We reveal the existence of two tipping points: (i) below a hydraulic gradient threshold, the hydrosystem suddenly degrades from a normal regime to saltwater intrusion, and (ii) a much larger hydraulic gradient is necessary for the recovery of the hydrosystem. The high hysteresis of the hydrosystem, due to the vertical karst conduit filling by saltwater, is responsible for the long duration of the degradation and saltwater intrusion. In a changing climate context, flow reversal at submarine karst springs could be more frequent and longer in the future due to sea level rise and a decrease in recharge, threatening inland or offshore freshwater resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The aquifers present in coastal areas constitute large freshwater resources that flow to oceans as submarine groundwater discharge (SGD) playing an important role for coastal ecosystems1 or constituting valuable sources of freshwater for several usages2. Thousands of submarine karst springs constitute point-source SGDs draining karst aquifers3 that can extend deeply as a consequence of the potential deep karstification process (during the last Messinian crisis4 in the Mediterranean area, for example), among which the Ayn Zayanah spring in Libya, probably the largest5. A few of them are subject to flow reversal and serve either as a sink or as a submarine source of freshwater like the Bali Bay springs in Greece6, Chekka springs in Lebanon7, Puerto Morelos8,9 springs in Yucatan peninsula or Andros Island in Bahamas10. This phenomenon threatens fresh groundwater resources, especially in a changing climate context11 as carbonate rocks and coastal karst aquifers constitute 15.7% of the global coastlines5. Saltwater intrusion processes have been widely studied in porous media for a long time12,13, including seasonal oscillations of water exchange between aquifers and the sea14. In karst aquifers, flow reversal or backflooding has been mainly studied on inland springs15. A few exceptions concern submarine springs in which the outflow of freshwater and inflow of sea water simultaneously run16 or alternate8,9 during short periods according to tides-driven sea-level fluctuations.

We conducted a study on the Vise submarine karst spring in the South of France, where an innovative monitoring system has been specifically designed in order to observe a long-duration (several months) flow reversal and highlight a rare hydrogeological phenomenon which is unique in terms of duration. This dataset, which includes simultaneous groundwater monitoring, allows for proposing a flow reversal mechanism at the submarine spring and modelling its impact on the aquifer.

Study area

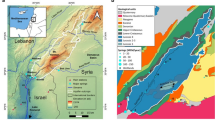

The Vise spring is a point-source SGD at the outlet of the Thau karst aquifer (300 m thickness) located close to Sète city (Fig. 1), South of France17,18. The Balaruc-les-Bains peninsula is located at the point of a natural convergence of different types of waters, including seawater from the Thau Lagoon and Mediterranean Sea, cold karst groundwater from the Aumelas Causse and Gardiole Massif, and mineralised hot thermal water rising from depth18. The karst and thermal water resources of the Thau hydrosystem are exploited both for drinking water supply and thermal activities (Balaruc-les-Bains is the largest thermal bath centre in France, with 55,000 visitors annually). Additionally, the Thau Lagoon supports an extensive shellfish aquaculture and fishery. Thus, water use conflicts appear between stakeholders during droughts as a consequence of water demand increase and the occurrence of occasional saltwater intrusions.

The Vise spring is located at the bottom of the Thau Lagoon at a depth of 29.55 m below the mean sea level (MSL) in the middle of a 50-m-long vent. The lagoon, made up of brackish water, is connected to the Mediterranean Sea. During the last 50 years (from 1967), eight occasional saltwater intrusions have been documented, suddenly inversing the water flow at the Vise submarine spring during a period varying from a few weeks to a few months19, among which a long-duration flow reversal has been monitored during its whole duration, from 28 November 2020 to 14 March 2022 and is analysed below.

Results and discussion

Hydrological measurements

The data time series of the main hydrological variables20 are illustrated in Fig. 2. The lagoon water level hS fluctuates most of the time between −0.2 m and 0.5 m a.s.l., except during a few high-water periods induced by South wind storms (Fig. 2a). The water level in the Jurassic aquifer, hP measured at Issanka (ISS) and CGE wells, fluctuates according to drought and natural aquifer recharge periods between 1.4 and 3.6 m a.s.l, respectively, 6.3 and 10.6 m a.s.l. (Fig. 2b, c). After the flow reversal shift, a sudden head increase is observed in numerous observation wells21 (‘piezometric rebound’ into the rectangle on Fig. 2c on CGE well example): this is analysed later in the discussion. The density ratio between the lagoon saltwater density (\({\rho }_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}\)) and fresh groundwater density (\({\rho }_{0}\)) is high, according to the salinization of the lagoon induced by the sea water inflow from the Mediterranean Sea and the evaporation process of the water under a hot and dry Mediterranean climate. The density ratio is highly correlated with the dry and humid seasons: the ratio increases during the summer reaching a peak just before the rainy season, then decreases after rainfall due to dilution effects (Fig. 2d). The hydraulic gradient between the aquifer and the lagoon is defined as:

a Lagoon water level hS*, b water level in the Jurassic aquifer hP* measured at ISS well, c water level in the Jurassic aquifer hP* measured at CGE well, d ratio between lagoon water and freshwater densities and daily rainfall data at Villeveyrac station, e hydraulic gradient between aquifer (at Issanka) and lagoon corrected from density effect, f flow rate, g water SEC, h water temperature measured at the Vise spring. *MSL as the reference level for hS and hP.

The hydraulic gradient (measured at the ISS well) fluctuates between a minimum value of 6.13 and 10.25 m (Fig. 2b). At the Vise spring (Fig. 2f–h), the data series starts on 25 June 2019, when the monitoring system was installed. During the first months, the flow rate Q (Fig. 2f), fluctuating between +0.050 and +0.210 m3/s, is well correlated to the water level into the aquifer (Fig. 2b-c). On 28 November 2020 at 09:40 AM (local time), when the hydraulic gradient between the lagoon and the aquifer (Fig. 2e) declines down to 6.13 m, a sudden flow reversal happens, the flow rate passing from +0.06 m3/s of exfiltration to −0.370 m3/s of infiltration flow into the karst aquifer. The infiltration flow rate decreases slowly down to about −0.150 m3/s during the following months before that a sudden flow change appears on 14 March 2022 at 08:30 AM (15 months later), with a return to normal conditions (+0.200 m3/s exfiltration flow rate) after a 3 days-long rainfall event (118 mm of rain between 12 and 14 March 2022) that suddenly recharged the aquifer (water level increase +3.98 m at ISS well, Fig. 2b). The water specific electrical conductivity (SEC) changes (Fig. 2g) are highly dominated by the flow reversal process: while exfiltrated fresh groundwater is characterised by low SEC (lower than 5 mS/cm), the infiltrated seawater induces a sudden and large increase of SEC measured at the spring up to 60 mS/cm. As soon as the spring starts to exfiltrate groundwater again, the SEC measured at the spring suddenly decreases. The water temperature (Fig. 2h) measured at the spring in normal conditions is close to 19 °C and higher than the average annual air temperature (15 °C), which is due to the contribution of deep hot thermal water to the groundwater flow at the spring19. The water temperature is mainly driven by the flow reversal process: it suddenly decreases at the flow reversal beginning as the lagoon water is cold during the winter and then suddenly increases at the end of the flow reversal. The impact of 2021 summer can be observed on water temperature with an increase up to 25 °C. During the FR period, 6.7 Mm3 of saltwater and more than 200,000 tons of salts infiltrated into the aquifer from November 2020 to March 2022, during a 15-month-long period.

A zoom on the flow reversal starting period shows in detail the meteorological conditions (Fig. 3a), the water level fluctuations into the lagoon and the associated hydraulic gradient changes between the aquifer (at ISS well) and the lagoon (Fig. 3b). The flow rate is slightly correlated to diurnal and semidiurnal tides as observed on other SGD22 or submarine karst springs9: the discharge rate increases (amplitude of 0.015 m3/s) with the decline of lagoon water level (0.04 m of amplitude). The flow reversal happens between 9:00 and 10:00 AM on 28th November 2020, after a sudden increase of lagoon level due to tides and a strong South wind. At the same time, the hydraulic gradient becomes historically low with a value of 6.13 m which is defined as the first tipping point (TP1) of the phenomenon.

a Time-evolution of wind velocity (left scale, lines) and direction (right scale, dots), b time-evolution of lagoon water level (dots), spring flow rate (left scale, plus symbols) and hydraulic gradient (line) between lagoon and aquifer at well ISS (right scale), during 10 days from 25 November 2020 to 4 December 2020.

In conclusion, the hydrological conditions at the beginning of the FR are the following: high water level in the lagoon due to tides and storm events, low water level in the aquifer due to drought period and high-density contrast between lagoon and aquifer waters due to the evaporation process in summer. Between 2019 and 2020, it is noticeable that several high-water level events in the lagoon did not induce any FR because the aquifer level was high during those periods and the hydraulic gradient remained higher than the tipping point (i > TP1).

Physical description of the flow reversal mechanism

The Vise spring constitutes the lower end of a vertical karst conduit and drains the Jurassic carbonate karst aquifer located under the Miocene cover that confines it (Fig. 4). The conduit, whose precise geometry is unknown and probably complex, is assumed, for simplicity, to be subvertical. Below the spring, the top of the Jurassic aquifer is located at a depth P.

In the lagoon, the water density ranges from 1020 to 1032 kg/m3, close to and even higher than seawater. In the aquifer, it varies from point to point and over time depending on the mixing of freshwater, saltwater and thermal water17,18,19. However, it is much lower than that of the lagoon water and, for simplification, we assume that is equal to \({\rho }_{0}\,\)= 999 kg/m3.

Considering the spring elevation as the vertical reference level, the water level in the lagoon HS (= hS + 29.55) varies over time according to the Mediterranean Sea level, tides and storm events. In the aquifer, the water level HP (= hP + 29.55) also varies over time according to the natural recharge to the aquifer, the water withdrawals for different uses and the drainage of the aquifer through the Vise spring and other secondary natural outlets.

In a normal regime (Fig. 4a), the density-corrected water level in the aquifer, measured close to the karst conduit (assuming therefore negligible head losses into the aquifer between the observation well and the spring), being higher than the level of the lagoon, the hydraulic gradient between the two water bodies induces vertical upward flows within the karst conduit. The freshwater of the Jurassic confined aquifer may outflow into the Thau lagoon. This normal state occurs as long as i > 0.

In the flow reversal regime (Fig. 4b), the density-corrected pressure in the aquifer becomes lower than that of the lagoon. The inversion of the hydraulic gradient (i < 0) induces a reversal of the vertical flow direction within the conduit, which becomes downward. The brackish water from the Thau lagoon invades the Jurassic aquifer.

Tipping points

The Vise karst hydrosystem transitions between two dynamic states that we describe according to the spring flow rate (defined as the state variable): the normal state characterised by upward flow (Q > 0) through the karst conduit and the flow reversal state characterised by downward flow (Q < 0) and salt intrusion into the aquifer (Fig. 5a). The driving (or control) parameter is the hydraulic gradient between the aquifer and the lagoon. In normal state, the positive flow rate at the spring linearly increases with the hydraulic gradient (Fig. 5a) that fluctuates according to meteorological forcing (droughts and recharge periods). This linear relationship is generally admitted for submarine springs23. When the hydraulic gradient decreases down to the tipping point for a minimum value of TP1 = 6.13 m, the flow rate suddenly becomes negative and the hydrosystem shifts from its normal regime to a flow reversal regime (on 28 November 2020). The not null TP1 value corresponds to head losses into the aquifer along the groundwater flow path between the ISS well and the karst conduit. After the flow reversal, the negative flow rate decreases while the aquifer head increases after recharge events. Once the aquifer head is high enough to reach a second tipping point (TP2 ≈ 10.25 m), the hydrosystem recovers and the flow rate becomes positive again (regime shift on 14 March 2022). The pathway of recovery highly differs from the pathway of degradation: the Vise hydrosystem is highly hysteretic. We define its hysteresis as the head difference between both tipping points:

a Vise karst hydrosystem states in a diagram of flow rate at the spring (state variable) versus hydraulic gradient between the aquifer at the ISS well and lagoon (control parameter). b General schematic diagram with hydrosystem states, stability and changes. Figure credit: J. Garbe, based on Scheffer et al. (Nature, 2001).

The stability of various states is illustrated in Fig. 5b using balls moving on an undulating surface, the hydrosystem being very stable (bold and dark colour balls) after regime shifts and unstable (dashed balls) just before them.

In a few minutes after the flow reversal, brackish water fills the karst conduit over a height P, causing an instantaneous increase in the hydraulic head within the aquifer at the bottom of the karst conduit equals to:

Then, the recovery to normal regime with upward flows requires a large increase in head able to counterbalance the situation: the hydrosystem is then very stable into the flow reversal regime (red ball in Fig. 5b). This is the reason why, in spite of a rapid set up, the flow reversal regime can last for a long time before that a major rainfall event contributes to a large increase of the hydraulic head in the aquifer. At that time (after high rainfall), a regime shift happens with a recovery to the normal state which is very stable as the karst conduit is now replenished with freshwater (green ball in Fig. 5b).

Modelling the piezometry response to flow reversal

After the FR happened on 28 November 2020, a hydraulic head rebound was measured (Fig. 2c, red rectangle) in all the monitored boreholes with water level rises ranging from 0.30 to 2.3 m21. The observed hydraulic head rebounds vary according to the distance of the observation point from the Vise spring as already observed during the past FR events19. These sudden head changes are well known by the local population because they create catastrophic flooding of underground garages and cellars in Balaruc-les-Bains city. Analytical solutions of the diffusivity equation, assuming a homogeneous confined porous aquifer below the vertical karst conduit that does not belong to the modelled domain (see Methods section), were tested on water levels measured in observation boreholes CGE and F6, characterised by various distance and depth conditions. The use of a porous-equivalent medium model in order to simulate groundwater flows into the karstified aquifer is supported by: (i) the dominance of small (centimetric) karst features present in the limestone as observed thanks to drilling-cores and (ii) the apparent hydrodynamic homogeneity of the aquifer as indicated by a constant diffusivity from well to well24. Solution 1 (radial flow regime) notably underestimates the variations in piezometry induced by the flow reversal; results are not presented. Solution 2 (one-dimensional flow regime) allows to represent the observed trends as illustrated in Fig. 6.

The P value required for matching the measurements is 70 m, which is coherent with a total depth to the top of the Jurassic aquifer close to 100 m (70 + 29.55 m) according to geological and geophysical information. If the piezometric fluctuations are not perfectly reproduced by the used analytical solution, we consider that the results are satisfactory and that the solution allows describing the major trends observed, in particular as a function of the distance to the Vise. This indicates that at this observation scale (several hundreds to thousands of metres), the hydrodynamic heterogeneities in the confined aquifer can be represented by ‘average properties’, i.e. an equivalent porous medium25 since local influences of karst conduits may average out over larger areas26,27. Nevertheless, there exist small discrepancies between the measurements and the model that can be related to the heterogeneity of the karst aquifer. The finding that a one-dimensional flow regime better matches the measurements suggests the importance of small karst conduits in the organisation of the flow geometry into the aquifer, that favour a linear hydrodynamic response compared to a radial response as would have been the case in a conventional porous aquifer. Such a flow regime has been documented in long-duration pumping tests conducted on wells intercepting karst conduits28 as the head changes firstly propagate into the highly permeable channels which act as long permeable fractures that drain surrounding limestone rock.

Modelling the flow reversal mechanism

The objective of this model is to reproduce the processes and not to try to simulate faithfully the head levels or flow measurements. The 2D model is implemented on the basis of realistic parameters (Fig. 7): it consists of a vertical section of a confined aquifer with a thickness e = 300 m, located under an impermeable layer of thickness P = 70 m (value obtained from here above analysis). A highly permeable vertical conduit located at its top in the centre of the modelled domain allows the connection with a 30-m thick saltwater body representing the Thau Lagoon. The hydraulic conductivity (K = 2.5 × 10−4 m/s), specific storage (SS = 10−5) and diffusivity (D = 25 m2/s) parameters of the aquifer are in agreement with values obtained from hydraulic tests interpretation24. The hydraulic conductivity of the vertical conduit is considered as a free parameter that has been calibrated in order to simulate an upward flow rate close to the average flow rate at the spring in normal regime.

Aquifer hydrodynamic properties and prescribed hydraulic head boundary conditions are presented (in orange at the spring and in dark blue at the aquifer lateral boundaries). A virtual piezometer P1 is located in the modelled domain in order to analyse the simulated head changes (see the modeling results at Fig. 8a).

Time-fluctuating hydraulic head boundary conditions have been prescribed in order to simulate the effects of (i) the water table changes into the aquifer between 2.5 m a.s.l during low flow conditions and 5 m a.s.l after an aquifer recharge event (32.05 < HP < 34.55) and the lagoon water levels changes ranging from 1.4 to 2.4 m a.s.l. after a storm event (30.95 < HS < 31.95). The problem is solved in transient conditions at a daily time step during a 2 year-duration period. The analysed simulation results (Fig. 8a, b) are (i) the hydraulic head computed at P1 location (aquifer top, 10 m away from the conduit, Fig. 7) and (ii) the flow rate computed into the vertical conduit.

The simulated scenario reproduces two hydrological cycles with high and low water conditions in the aquifer (Fig. 8a). The lagoon also undergoes two identical short-duration water level rises, separated by 6 months. Each event consists of a sudden rise and fall of the water level of 1 m in 7 days, due for example to a wind-driven lagoon level rise. During the first event (starting after 30 days of simulation), the aquifer head is +3 m a.s.l. at the boundary of the aquifer (at 4000 m from the conduit) and no inversion of flows is observed. On the other hand, when the second event occurred after 210 days, the aquifer head had gradually dropped to +2.5 m (drop linked to both the absence of rainfall and natural drainage), which generated a sudden flow reversal. The later disappears only after that the aquifer head has risen to +5 m a.s.l. following a major recharge episode for example. A sensitivity analysis has shown that this value is the minimum head rise that should be prescribed at the aquifer boundary in order to produce a recovery of the hydrosystem. The diagram of the simulated hydrosystem state according to the hydraulic gradient (Fig. 8b) follows the same path as the observed one illustrated in Fig. 5a.

The flow rate time series simulated at the spring highlights the succession of three major periods (Fig. 8a):

- Period 1: normal regime (between t = 0 and t = 210 days). Varying between +0.060 and +0.040 m3/s, the flow rate at the outlet is positive (upward from the aquifer to the lagoon) and proportional to the hydraulic gradient (Fig. 8b). The strong increase of the lagoon water level (at t = 30 days) induces a sudden decrease of the spring flow rate but does not induce any flow reversal.

- Period 2: flow reversal regime (between t = 210 and t = 445 days). Following a strong and sudden rise of the lagoon water level concomitant with a lower water level in the aquifer (2.5 m), the flow rate at the spring becomes suddenly negative, directed downward from the lagoon to the aquifer. The hydraulic head computed into the aquifer at location P1 shows a piezometric rebound at that time as observed in our case study (red rectangle in Fig. 2c). It remains higher than previously during the whole period 2 (Fig. 8a), being an impact of the filling of the vertical conduit by high-density saltwater.

- Period 3: recovery to the normal regime (between t = 445 and t = 730 days). Following a rise in the piezometric level at the boundary of the aquifer (e.g. induced by groundwater recharge from heavy rainfalls for example), the flow rate at the outlet becomes positive again with upward flow in the karstic conduit. The sensitivity analysis conducted on the model indicates that a water level rise in the aquifer of at least 2.50 m is necessary to reinstall the normal regime (hysteresis of the modelled system HY = TP2−TP1 = 2.90 m).

Karst geometry and hysteresis

The hysteresis of the Vise karst system, defined as the head difference between both tipping points, is high (HY = 4.12 m). This induces a very long duration of the flow reversal crisis because a large water level increase in the aquifer (provoked by a high aquifer recharge event) is necessary for the recovery of the system. In that way, the Vise karst spring is highly specific. While other flow reversal phenomena known in the World8,9 are unstable according to tides or small sea level changes (with flow directions often changing during the crisis period), the flow reversal at the Vise hydrosystem is very stable in degraded state due to saltwater intruded into the vertical karst conduit which acts as an obstruction to upward flows. This uniqueness is due to the existence of a vertical karst conduit connecting the karst aquifer to the sea/lagoon (Fig. 9a, b) as observed at Chekka springs in Lebanon7 or Andros Island in the Bahamas10. On the contrary, the inversion of flow direction is easier in a horizontal karst conduit (Fig. 9c) as observed in Puerto Morelos point-source SGD8,9 where small sea level fluctuations provoked by tides induce daily flow oscillations. In a few examples like the Roubine spring16, simultaneous outflow of freshwater can coexist with inflow of seawater into the same horizontal karst conduit (Fig. 9d).

Conclusion

The flow reversal at the Vise submarine spring is induced by an increase in the lagoon water level during low flow conditions in the aquifer. The high salinity of the lagoon water can be an exacerbating factor. The sudden water level increase observed in the aquifer after each flow reversal is due to the instantaneous filling of the vertical karst conduit connecting the spring to the confined aquifer with denser water. The recovery to the normal regime necessitates a high water level rise of about 2.5 m, able to counterbalance the hydraulic head rise due to the saltwater intrusion; this is the reason why the hydrosystem is highly hysteretic and the duration of the flow reversal degradation is very long (several months). This phenomenon threatens the fragile equilibrium of water resources in the Thau area, where several economic activities rely on freshwater. Further investigations are now being conducted in order to forecast and mitigate the impacts of flow reversal on fresh groundwater resources.

Such hysteretic behavior of submarine springs is typical of karst systems dominated by a vertical conduit. It could be more frequent in the future due to climate change, threatening inland or offshore freshwater29 resources located in karst aquifers. It is expected that deeper karst aquifers developed during the Messinian crisis4 and connected to the sea with a longer vertical karst conduit are highly vulnerable to this flow reversal phenomenon. In the latest case, the necessary water level rise for the recovery process, proportional to the length of the vertical karst conduit P, is higher and the phenomenon could even become irreversible, inducing permanent saltwater intrusion.

Methods

The dataset of Fig. 2 is presented and downloadable in the Mendeley directory: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/fpdkw88z84/2.

Vise submarine spring monitoring system

An experimental device was specially designed for collecting and measuring the flow rate at the submarine spring (Fig. 10), the detailed description is given in ref. 21. The submarine spring discharge was measured with a 1-m-diameter flowmeter (Optiflux 4300W model, Krohne) connected to a data logger installed on the lagoon shore. Water SEC and temperature of the submarine spring were measured in the experimental device with two OTT PLS C in situ probes connected on land to an OTT NetDL data logger equipped with a GPRS modem. Flow rates, SEC and temperature were measured at a time step of 5 min between 26 June 2019 and today. During the flow reversal period, the SEC and temperature measured are those of the lagoon water. These measurements make it possible to qualify the physicochemical properties of the lagoon saltwater infiltrated through the karst spring during degradation events. The integration of the product between the negative flow rate and the water salinity at the spring provides the total infiltrated salt mass. Water densities and salinities have been calculated using SEC and temperature data following the thermodynamics equation of seawater (TEOS−10)30.

Lagoon data

The lagoon water level was measured in a strainer tube using an ultrasonic sensor; the detailed description is given in ref. 21. The data is expressed in metres above sea level. Measured lagoon water level fluctuations were repeatedly checked at the reference point using a manual water level gauge.

The raw salinity and temperature data measured at the lagoon station 104-P-0001 located about 1 km from the Vise spring were acquired on a weekly time step31. Interpolated data to daily time steps have been used to estimate the variations of the water density in the lagoon before the flow reversal period (period from 1 January 2017 to 28 November 2020).

Daily rainfall data have been measured at the Villeveyrac meteorological station (location on Fig. 1), located 8.3 km northwest of the Vise spring, in the spring catchment.

Groundwater data

A detailed description of the Groundwater observatory is given in refs. 21,32. Water level, SEC at 25 °C and temperature of karst aquifer were measured at springs and boreholes with Dipper PETC data logger (SEBA Hydrometry) equipped with a GPRS modem at a time step of 15 min between 1 January 2017 and today.

Analytical solution for modelling the piezometric wave into the confined aquifer

After the flow reversal, piezometric rebounds are observed in the confined aquifer. They vary according to the distance between the observation point and the Vise spring. This phenomenon is explained by the propagation of the pressure disturbance induced at the Vise karst conduit bottom within the Jurassic confined aquifer. This phenomenon can be approached by analytical solutions of the diffusivity equation, assuming a homogeneous confined porous aquifer of very large size.

Two solutions describing the propagation of an abrupt pressure change at the origin (Vise spring) are given in Table 1 for (i) radial flow and (ii) one-dimensional flow configurations, along with the associated specified initial and boundary conditions, where H is the hydraulic head (m), D the aquifer diffusivity (m2/s), r and x the distance from the origin to the observation point (m), \({\rho }_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}\) and \({\rho }_{0}\) the density of lagoon and freshwater, respectively, P the length of the vertical karst conduit.

Numerical modelling of the flow reversal mechanism

A finite element numerical model was implemented in order to simulate the mechanism of the flow reversal phenomenon at the karst spring. The FEFLOW (Finite Element subsurface FLOW and transport system) groundwater modelling code33 has been applied on a two-dimensional cross-sectional vertical domain. It simulates the coupled flow and mass transport processes, accounting for the dependence of fluid density on salt concentration.

References

Luijendijk, E., Gleeson, T. & Moosdorf, N. Fresh groundwater discharge insignificant for the world’s oceans but important for coastal ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 11, 1260 (2020).

Moosdorf, N. & Oehler, T. Societal use of fresh submarine groundwater discharge: an overlooked water resource. Earth Sci. Rev. 171, 338–348 (2017).

Fleury, P., Bakalowicz, M. & de Marsily, G. Submarine springs and coastal karst aquifers: a review. J. Hydrol. 339, 79–92 (2007).

Audra, P. et al. The effect of the Messinian deep stage on karst development around the Mediterranean Sea. examples from Southern France. Geodin. Acta 17, 389–400 (2004).

Goldscheider, N. et al. Global distribution of carbonate rocks and karst water resources. Hydrogeol. J. 28, 1661–1677 (2020).

Breznik, M. Development of the brackish karstic spring Almyros in Greece. Geologija 31, 555–576 (2021).

Bakalowicz, M. et al. Hydrogeological settings of karst submarine springs and aquifers of the Levantine coast (Syria, Lebanon). Towards their sustainable exploitation. In Proc. TIAC’07 International Symposium on Technology of Seawater Intrusion into Coastal Aquifers Vol. 7, 721–732 (Instituto Geologico y Minero de Espana, 2007).

Parra, S. M., Valle-Levinson, A., Mariño-Tapia, I. & Enriquez, C. Salt intrusion at a submarine spring in a fringing reef lagoon. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 120, 2736–2750 (2015).

Parra, S. et al. Seasonal variability of saltwater intrusion at a point-source submarine groundwater discharge. Limnol. Oceanogr. 61, 1245–1258 (2016).

Stringfield, V. T. & LeGrand, H. E. Effects of karst features on circulation of water in carbonate rocks in coastal areas. J. Hydrol. 14, 139–157 (1971).

Ferguson, G. & Gleeson, T. Vulnerability of coastal aquifers to groundwater use and climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 342–345 (2012).

Reilly, T. E. & Goodman, A. S. Quantitative analysis of saltwater-freshwater relationships in groundwater systems—a historical perspective. J. Hydrol. 80, 125–160 (1985).

Basack, S., Loganathan, M. K., Goswami, G. & Khabbaz, H. Saltwater intrusion into coastal aquifers and associated risk management: critical review and research directives. J. Coast. Res. 38, 654–672 (2022).

Michael, H. A., Mulligan, A. E. & Harvey, C. F. Seasonal oscillations in water exchange between aquifers and the coastal ocean. Nature 436, 1145–1148 (2005).

Albéric, P. River backflooding into a karst resurgence (Loiret, France). J. Hydrol. 286, 194–202 (2004).

Drogue, C. & Bidaux, P. Simultaneous outflow of fresh water and inflow of sea water in a coastal spring. Nature 322, 361–363 (1986).

Aquilina, L., Ladouche, B., Doerfliger, N. & Bakalowicz, M. Deep water circulation, residence time, and chemistry in a karst complex. Ground Water 41, 790–805 (2003).

Aquilina, L. et al. Origin, evolution and residence time of saline thermal fluids (Balaruc springs, southern France): Implications for fluid transfer across the continental shelf. Chem. Geol. 192, 1–21 (2002).

Petre, M. A. et al. Hydraulic and geochemical impact of occasional saltwater intrusions through a submarine spring in a karst and thermal aquifer (Balaruc peninsula near Montpellier, France). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24, 5655–5672 (2020).

Ladouche, B. et al. Dataset on onshore groundwaters and offshore submarine spring of a Mediterranean karst aquifer during flow reversal and saltwater intrusion. MENDELEY. https://doi.org/10.17632/fpdkw88z84.2.

Ladouche, B. et al. Dataset on onshore groundwaters and offshore submarine spring of a Mediterranean karst aquifer during flow reversal and saltwater intrusion. Data Brief 50, 109557 (2023).

Taniguchi, M. Tidal effects on submarine groundwater discharge into the ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 2–3 (2002).

Valle-Levinson, A., Mariño-Tapia, I., Enriquez, C. & Waterhouse, A. F. Tidal variability of salinity and velocity fields related to intense point-source submarine groundwater discharges into the coastal ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 56, 1213–1224 (2011).

Ladouche, B. et al. DEM’Eaux Thau—Synthèse et Valorisation Préliminaire Des Données Sur l’hydrosystème de Thau (34) 313 (BRGM, 2019). http://infoterre.brgm.fr/rapports/RP-68483-FR.pdf.

Hartmann, A., Goldscheider, N., Wagener, T., Lange, J. & Weiler, M. Karst water resources in a changing world: Approaches, of hydrological modeling. Rev. Geophys. 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013RG000443 (2014).

Abusaada, M. & Sauter, M. Studying the flow dynamics of a karst aquifer system with an equivalent porous medium model. Groundwater 51, 641–650 (2013).

Scanlon, B. R., Mace, R. E., Barrett, M. E. & Smith, B. Can we simulate regional groundwater flow in a karst system using equivalent porous media models? Case study, Barton Springs Edwards aquifer, USA. J. Hydrol. 276, 137–158 (2003).

Maréchal, J. C., Ladouche, B., Dörfliger, N. & Lachassagne, P. Interpretation of pumping tests in a mixed flow karst system. Water Resour. Res. 44, 5401 (2008).

Post, V. E. A. et al. Offshore fresh groundwater reserves as a global phenomenon. Nature 504, 71–78 (2013).

Millero, F. J., Feistel, R., Wright, D. G. & McDougall, T. J. The composition of Standard Seawater and the definition of the Reference-Composition Salinity Scale. Deep Sea Res. Part Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 55, 50–72 (2008).

Grondin, E., Fari, C. & Duval, M. SURVAL. Plaquette Explicative à l’usage Des Utilisateurs de SURVAL. https://doi.org/10.13155/89133 (2022).

Ladouche, B. et al. Inversac de La Source Sous-Marine de La Vise Sous La Lagune de Thau: Mécanisme et Modélisation. BRGM/RP-70839-FR, p. 103 (BRGM, 2022).

Diersch, H. J. G. FEFLOW: Finite Element Modeling of Flow, Mass and Heat Transport in Porous and Fractured Media. FEFLOW: Finite Element Modeling of Flow, Mass and Heat Transport in Porous and Fractured Media Vol. 9783642387 (Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2014).

Acknowledgements

This research has been supported by the FEDER-CPER (European Community, French State and Occitanie Region), Agence de l’Eau Rhône Méditerranée Corse, Balaruc-les-Bains, Syndicat Mixte du Bassin de Thau, Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole and BRGM through the DEM’Eaux Thau project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.L. and J.C.M. designed the study. C.L. coordinated the project. B.L. and C.L. collected the data. J.C.M. and P.P. performed the modelling. B.D. and V.H. contributed to the data analysis. J.C.M. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Nico Goldscheider, Ismael Marino-Tapia and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Joe Aslin.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maréchal, JC., Ladouche, B., Lamotte, C. et al. Hysteresis of submarine karst springs reveals tipping points in flow reversal and saline intrusion phenomena. Commun Earth Environ 6, 697 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02522-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02522-8