Abstract

Convective dust events pose a health threat as they impact urban air quality, but traditional air quality monitoring methods do not always capture them. Although the impact of these convective dust events is important, they are still poorly understood. Limitations of temporal and spatial observations have an impact on the understanding of their impact on urban air quality. Many urban locations prone to these convective dust events do not have any reference sensors or have a limited number. And these reference sensors are based on hourly measurements, which mask the impact of these convective dust events. This perspective will provide insight into these short-duration convective dust events and their impact on the urban environment, using two locations. Highlighting the uncertainties and the suggestions to solve them using dense networks of low-cost sensors, which will help improve and understand the true impacts of these convective dust events on urban air quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Convective dust events pose a threat to urban air quality, but are not always captured by traditional air quality monitoring methods. Here, the measurement and impact of these events on urban settings are examined with reference to two cities in the USA. But before digging into convective dust events and their impact on urban air quality, we need to understand that not all dust events are convective, and not all dust events are defined as dust storms.

Dust events, including blowing dust events (BDE) and dust storms (DS), are common in arid and semi-arid regions1,2. In both, the strong wind lifts dust particles into the air, which reduces horizontal visibility. In BDE, the horizontal visibility can be reduced to ≤10 km, but >1 km, while in DS, visibility decreased to ≤1 km3. Two main meteorological disturbances (synoptic and convective) can cause an increase in wind speed, leading to the formation of BDE or DS. Synoptic disturbances are defined as a large-scale process (such as high/low-pressure systems, fronts, or jet streams), impacting a large area over a long period (hours to days), while convective disturbances are a small-scale (localized) process that occur over a small area for a short duration from a few minutes up to a few hours4,5. Observations of dust events caused by a combination of synoptic and convective disturbances have been observed, where the dust events were initiated by a synoptic disturbance but intensified by a convective disturbance. Although they are rare, their impact is still unclear6.

Convective dust events are caused by thunderstorms’ outflow, boundaries, and downbursts. The melting and evaporating droplets and ice crystals of these thunderstorms create a downdraught (cold pool) that reaches the ground and spreads horizontally1. These strong winds can lift dust particles forming a wall of dust known as a haboob7, even reducing visibility to near zero, as shown in Fig. 1. Observations of dust with haboob features have been observed even without the formation of thunderstorms, e.g., squall line or cold front8,9, or due to a combination of synoptic and convective10. But the majority of the haboobs are caused by convective disturbances, almost half of the dust events in the southern Sahara11,12, 40% of those in West Africa13, and ~70% of the dust events in Phoenix, Arizona, USA are convective dust events5. These convective dust events are common across the world, from Africa1,14, to Asia9,15, Australia16, the Middle East17,18, and even across the USA4,19,20. Most occur in spring and summer14,17,18. These convective dust events can occur at any hour of the day1,17,21. Majority forms during the late afternoon and early evening hours, when convective storm formation occurs, but observations were also made in the middle of the night and early morning hours5,6.

a Haboob from July 4, 2024, photograph by Dr Mary Robinson, used with permission. b Haboob images in Lubbock, Texas, from October 17, 2011, show the approaching haboob and visibility at different time points, from a camera located on the 12th floor of the Atmospheric Science Group at Texas Tech University, photograph provided by Dr Eric Bruning, used with permission.

Although most of these convective dust events last less than an hour, longer events have been recorded21,22. The haboobs front can be tens and hundreds of km wide, travel over a long distance, and reach >1 km height1,4,13, as shown in Movie 1, in visible light (Movie 1a), and using dust RGB product (Movie 1a), where the haboob is >300 km wide, passes across Texas and Mexico, and travels over a distance >500 km.

Many of the convective dust events pass over urban areas, impacting people's lives and well-being. Convective dust events (BDE and DS) and the dust particles that are emitted during these events can impact the Earth's ecosystem, radiation10,23, cloud formation, and precipitation processes24,25, as well as the atmospheric vertical electric field26. These convective dust events pose a safety hazard as they can cause car injuries and fatalities27,28. Although many studies examine the health impact of dust events in general, only a few have examined the impact of convective dust events, also known as “haboob lung syndrome”. Panikkath et al.29,30 reported on healthy patients who were hospitalized a few days after exposure to convective dust events. All patients experienced acute lung infiltrates/pneumonia symptoms, and one even passed away29,30.

Another way to examine the impact of these convective dust events is to look at their impact on air quality. Observations of air quality are based on the concentrations of PM10 and PM2.5 (defined as particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of up to 10 and 2.5 μm, respectively). These PM sensors are, in most cases, reference sensors defined as official regulatory PM sensors operated by the EPA and provide hourly PM values. Many studies from across the world presented an increase in dust particle concentrations at the time of the convective dust events20,31,32,33. Yet, the traditional way to examine their impact on air quality is based on the recommended daily threshold for exposure. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a daily threshold of 45 and 15 μg m−3 for PM10 and PM2.5, respectively34, while the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recommends a daily threshold of 150 and 35 μg m−3 for PM10 and PM2.5, respectively35. Although many dust events (BDE & DS) can exceed these daily thresholds2,4,36,37,38, measurements from around the world of convective dust events show that the PM concentrations do not exceed these daily thresholds5,21,31,33,39,40. It should be noted that these recommendations of daily thresholds were developed based on epidemiological studies that estimate chronic exposure to anthropogenic pollution41, while convective dust events represent acute exposure to natural particles. Previous studies demonstrated that short-term (acute) exposures to high anthropogenic emissions can lead to degradation of human health42,43,44. Highlighting the fact that sub-daily exposure should be considered, as the peak PM concentration may capture the health effects of ambient PM better than daily averages43,44. Yet, the health consequences of short exposure to dust particles (e.g., from convective dust events) are unclear, and there are no guidelines to evaluate these short-term exposures45. It is possible to assume that since most observations of dust events, in general, were based on daily and hourly PM values, the impact of convective dust events on PM concentrations and hence on human health is underestimated.

Two urban locations prone to convective events in the USA (Lubbock, Texas, and Phoenix, Arizona) will be used to highlight the impact of convective dust events on air quality. Lubbock, located in West Texas, is an urban city (~250,000 people) surrounded by a rural agricultural area. This area experienced an average of 29 ± 16 dust events per year6. Some claim it is the dustiest place in the Great Plains or even across the USA46,47. Convective dust events represent ~33% of the dust events in this region, mainly in late spring to early summer6. Several studies examine the impact of these convective dust events on air quality21,40. Kelley and Ardon-Dryer21 examined convective dust events from 2000 to 2019 and found that none of these convective dust events exceeded the EPA PM2.5 recommended daily threshold. Ardon-Dryer and Kelley39 measured two convective dust events and found similar findings where the daily PM10 and PM2.5 did not exceed the EPA daily threshold. Yet, observations based on hourly PM10 and PM2.5 values were 6 to 9 times higher (respectively) than the daily values, and concentrations based on 10-min averages were ~4 times higher than those measured based on hourly averages and 24–47 times higher compared to daily concentrations. Even the concentrations of PM1 (particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of up to 1 μm) and the number concentrations of particles in the range of 0.3–1 µm increased during these convective dust events, highlighting the importance of these small particles as they can impact people's health39.

The October 17, 2011, Habbob shown in Fig. 1b in Lubbock, Texas, highlights the severity of these intense convective dust events. During this event, the wind speed and gust reached 21.6 ms−1 and 28.3 ms−1 (respectively). This specific dust event was defined as DS as visibility by the local meteorological station reported visibility <1 km. Visibility as low as 0.4 km was reported for ~20 min, shown by the complete blackness in Fig. 1 (17:40 local time-LT). The PM2.5 daily average during this day was 23.5 μg m−3, below the EPA daily PM2.5 threshold, while hourly PM2.5 concentration at the peak of the dust was 167 μg m−3. While observations only based on daily average values would make us think this day was fine and did not have any reason for concern, the high hourly values and Fig. 1b highlight the severity of this DS. This also supports the suggestions by Ardon-Dryer et al.40 who stated that averaging PM concentration over the entire day will mask the severity and true impact of these convective dust events.

Similar findings were found for Phoenix, Arizona, which is a large urban area with several million people who experience many convective dust events. About 70% of the total dust events in this area are convective dust events5. Several convective dust events in Phoenix exceeded the WHO and EPA daily guidelines. For example, the 5 July 2011 dust had a PM10 daily value of 225 μg m−3, hourly PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations during this day reached 1974 μg m−3 and 907 μg m−3 respectively4. Not far from Phoenix, PM10 hourly concentrations reached 2316 μg m−3 48. Ardon-Dryer and Aziz49 examined 93 convective dust events in Phoenix between 2015 and 2021 and found that many of these convective dust events did not exceed the EPA and WHO PM10 daily thresholds. They indicated that even if the convective dust events were below the EPA and WHO thresholds, they still had very high PM10 concentrations. For example, the dust event of August 16, 2021, had daily PM10 concentrations of 40 ± 86 μg m−3, hourly concentrations of 434 μg m−3 at 23:00 LT, and 10-min PM10 concentrations of 1814 μg m−3 at 23:00 LT. The 10-min PM10 concentrations were 4 times higher than the hourly values and 45 times higher than the daily values. The convective dust event that took place on July 8, 2018, had daily PM10 concentrations above the EPA and WHO thresholds (385 ± 1068 μg m−3). The hourly PM10 concentration at the peak of the dust was 4288 μg m−3 (at 23:00 LT), while 10-min PM10 concentrations at the peak of the dust reached 8129 μg m−3 (at 23:20 LT), which were double the hourly value and 20 times higher than the daily values. These high short-duration (10-min) PM10 concentrations have been observed regardless of whether the convective dust events were above or below the EPA and WHO daily thresholds or where they were defined as BDE or DS49.

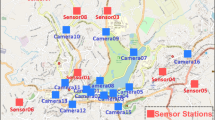

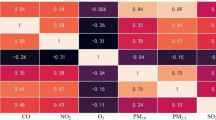

Observations from multiple PM sensors allow for monitoring the temporal and spatial movement of these convective dust events as they impact the urban air quality. Lubbock has only one reference sensor that monitors PM2.5 concentration, while Phoenix has several reference sensors with PM10 and PM2.5 stations. Figure 2 provides examples of several convective dust events from the greater Phoenix area as they pass the urban area. It should be noted that these examples were taken from Ardon-Dryer and Aziz49 study, who used hourly and 10-min PM10 values from multiple local reference sensors.

Convective dust event impacts a small area of the urban area (a, b), as well as convective dust events that impact on air quality across many neighborhoods of the urban area (c). Data retrieved from Ardon-Dryer and Aziz49 with modification.

The convective dust event of August 27, 2015 (Fig. 2a) had a large increase in PM10 concentrations at only one station (4-13-4010), hourly PM10 concentrations reached 1784 μg m−3 at 15:00 LT. The other sensors, who were active at that time, only reached a maximum hourly PM10 concentration of 162 μg m−3 (measured by station 4-13-4016, the closest one to 4-13-4010). This impact can also be seen with the short-term observations, which showed that 10-min PM10 concentrations reached 5401 μg m−3 (sensor 4-13-4010 at 15:20 LT); the nearest sensors (station 4-13-4016) reported at the same time 10-min PM10 concentrations reached 499 μg m−3. It took another 30 min for the other sensors across Phoenix to detect this dust, and the increase in these sensors did not exceed 10-min PM10 concentrations of 350 μg m–3.

Another example that highlight the spatial impact of these events, is the convective dust events of July 23, 2017 (Fig. 2b). In this case the convective dust event first impacted two PM10 stations (sensors 4-13-4006 and 4-13-4004), but the impact was very small, at 18:00 LT hourly PM10 concentration by these two sensors reached 184 and 142 μg m−3 (4-13-4006 and 4-13-4004, respectively). By 19:00, the dust reached station 4-13-4009, and hourly PM10 concentrations maxed at 1230 μg m−3. The two sensors in the west part of the area (station 4-13-4016 and 4-13-4010) did not have a strong increase in hourly PM10 concentration remained below 35 μg m−3. Observations based on 10-min PM10 concentrations allow us to observe how these dust particles pass through the urban area. Sensor 4-13-4006 was the first to detect the increase of PM10 concentrations (367 μg m−3 at 18:20 LT). Ten minutes later, at 18:30 LT, sensor 4-13-4004 detected the first increase of PM10 concentrations (238 μg m−3). Sensor 4-13-3003 was the next to detect the dust at 18:50 LT (232 μg m−3), just 20 min later, an increase in PM10 concentrations was observed by sensor 4-13-3002. At 19:20, sensor 4-13-4009 detected the dust where 10-min PM10 concentrations were 2948 μg m−3, 10 min later the PM10 concentrations reached 3269 μg m−3 (at 19:30 LT), by 20:00 LT the concentrations reported by this sensor went back to the background onrtrations measured before the dust. Senors 4-13-4010 and 4-13-4016 had a very small increase in PM10 concentrations around 19:50 LT (10-min PM10 concentrations reached 62 and 101 μg m−3, respectively).

While these two examples highlight that the impact of convective dust events can be on some part of the urban area, some convective dust events may impact the entire urban area, as the one presented in Fig. 2c. Figure 2c presents a convective dust event from August 23, 2017. Almost all of the eight PM10 stations observed an increase in PM10 concentrations. An increase in PM10 concentrations was first observed by stations 4-13-4006 and 4-13-4004, then by stations 4-13-4009, 4-13-3002, and 4-13-3003, and later by 4-13-4010 and 4-13-4016. The maximum hourly PM10 concentrations reported by all these stations ranged from 492 μg m−3 (by 4-13-4016) up to 1517 μg m−3 (by 4-13-3003). While 10-min PM10 concentrations ranged from 861 μg m−3 (by 4-13-4016) to 2601 μg m−3 (by 4-13-3003). Although high PM10 concentrations were observed during this dust event, none of the stations had daily PM10 values that exceeded the EPA daily threshold (150 μg m−3).

Although the impact of these convective dust events is important, they are still poorly understood for both their dynamics and the amount of dust particles they may lift into the atmosphere23,50,51. The main issues when looking at the impact of these convective dust events on air quality can be temporal and spatial. Only a few urban locations impacted by convective dust events have multiple reference PM sensors that spread across the urban environment to monitor these convective dust events on air quality. As shown in Fig. 2, some of these convective dust events may affect the entire city, while others can only affect several neighborhoods. Observation of the spatial aspect of these convective dust events depends on the spread of air quality sensors across the city. Unfortunately, many locations prone to convective dust events do not have any air quality sensors or have only one, which may or may not be impacted by these convective dust events40,52. Hence, the true impact of these convective dust events on the local air quality is still limited.

As shown in the examples presented another aspect that should be considered is the duration of most of these convective dust events which is fast (less than 1-h), meaning traditional air quality observation and methods (e.g., reference senors), which are based on hourly values, may mask the impact of these convective dust events, miss them completely, or not report their true impact on air quality40. Therefore, short-duration measurements (ideally those that can be reported every 5 or 10 min) will allow us to capture these convective dust events and the dust particle concentrations, and allow document and understand their impact on air quality.

One way to overcome these spatial and temporal issues is with the use of low-cost sensors that will be spread across the urban area and provide short-duration PM measurements. Yet many of these commercially low-cost sensors cannot detect coarse dust particles or accurately measure PM concentrations53,54. Recent studies found that some higher-grade low-cost sensors (e.g., the optical sensor Alphasense OPC-N3) could be efficient in detecting dust particles during dust events54,55,56, which is in use in one of the commercially low-cost sensor companies. The efficiency of many of these commercially low-cost sensors is still questionable, mainly for their accuracy in detecting coarse dust particles, and therefore, they require additional investigation, mainly in dust-prone regions and those with convective dust events. Dense networks of these low-cost sensors (with appropriate calibration, and with the ability to take short-term measurements, each minute) may help improve the ability to capture these short convective dust events, allowing to understand the true impacts of these convective dust events on air quality.

Another issue that should be mentioned is the inability to accurately report atmospheric PM concentrations during extreme high-dust events. Some convective dust events may have very high PM concentrations that will exceed the upper limit threshold of some of the air quality sensors used as regulatory reference sensors, as presented in Rodríguez and López-Darias57. Although none of the dust events presented in this work57 were convective dust events, it is possible that some convective DS could have very high PM concentrations, above the upper limit of the reference sensors, not allowing the detection of the true atmospheric particle concentrations. To overcome this issue, it is recommended that sensors with a higher upper limit threshold be used in areas prone to dust.

In addition to the limitation of measuring the air quality impact of these convective dust events, many models cannot accurately simulate or predict these convective dust events, and cannot capture the correct particle sizes or concentrations emitted during these convective dust events2,13,14,23,50,51,58,59. Improving modeling for convective dust events requires simulating the strong winds and cold pools generated. Studies suggest that improvement of the prediction of convective dust events requires parametrization that uses downdraft mass flux60, use of lightning assimilation13, and a non-hydrostatic model with high resolution2. Reliable predictions of convective dust events are necessary to help determine their effects on air quality, but also their impact on visibility and the radiation budget, which can help predict how these convective dust events will change in the future10,59. Evaluation of the impact of these convective dust events on air quality and human health is needed to quantify their risk. Such knowledge will help to develop better mitigation practices and allow the creation of prediction and warning systems that could be used to alert the public, mainly in regions prone to these convective dust events.

References

Roberts, A. J. & Knippertz, P. The formation of a large summertime Saharan dust plume: convective and synoptic-scale analysis. JGR Atmos. 119, 1766–1785 (2014).

Vukovic, A. et al. Numerical simulation of “an American haboob”. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 3211–3230 (2014).

World Meteorological Organization. Manual on Codes-Regional codes and national coding practices. Retrieved from http://epic.awi.de/29966/1/WMO2011h.pdf (2019).

Raman, A. et al. Revisiting haboobs in the southwestern United States: an observational case study of the 5 July 2011 Phoenix dust storm. Atmos. Environ. 89, 179–188 (2014).

Sandhu, T. et al. Identification of dust events in the greater Phoenix area. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 15, 102275 (2024).

Robinson, M. C. & Ardon-Dryer, K. Characterization of 21 years of dust events across four west Texas regions. Aeolian Res. 67–69 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeolia.2024.100930 (2024).

Sutton, L. J. Haboobs. Q. J. Roy. 51, 25–30 (1925).

Lee, J. A. & Gill, T. Multiple causes of wind erosion in the Dust Bowl. Aeolian Res. 19, 15–36 (2015).

He, Y. et al. RANS simulation of local strong sandstorms induced by a cold pool with vorticity. Atmosphere 11, 321 (2020).

Bukowski, J. & van den Heever, S. C. Convective distribution of dust over the Arabian Peninsula: the impact of model resolution. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 2967–2986 (2020).

Heinold, B. et al. The role of deep convection and nocturnal low-level jets for dust emission in summertime West Africa: estimates from convection-permitting simulations. JGR Atmos. 118, 4385–4400 (2013).

Marsham, J. H. et al. Meteorology and dust in the central Sahara: observations from Fennec supersite-1 during the June 2011 intensive observation period. JGR Atmos. 118, 4069–4089 (2013).

Foroutan, H. & Pleim, J. E. Improving the simulation of convective dust storms in regional-to-global models. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 9, 2046–2060 (2017).

Pantillon, F. et al. A parameterization of convective dust storms for models with mass-flux convection schemes. J. Atmos. Sci. 72, 2545–2561 (2015).

Banerjee, P. et al. The unusual severe dust storm of May 2018 over Northern India: genesis, propagation, and associated conditions. JGR Atmos. 126, e2020JD032369 (2021).

Strong, C. L. et al. Dust transporting wind systems in the lower Lake Eyre Basin, Australia: a preliminary study. Aeolian Res. 2, 205–214 (2011).

Firouzabadi, M. et al. The climatology of severe convective storms in Tehran. Atmos. Res. 221, 34–45 (2019).

Karami, S. et al. Investigation and model simulation of dry and moist (haboob) convective dust storms in Yazd Province, central Iranian plateau. Arab. J. Geosci. 16, 241 (2023).

Lei, H. & Wang, J. X. L. Observed characteristics of dust storm events over the Western United States using meteorological, satellite, and air quality measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 7847–7857 (2014).

Eagar, J. D. et al. The characterization of haboobs and the deposition of dust in Tempe, AZ from 2005 to 2014. Aeolian Res. 24, 81–91 (2017).

Kelley, M. C. & Ardon-Dryer, K. Analyzing two decades of dust events on the southern Great Plains region of West Texas. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 12, 101091 (2021).

Nickling, W. G. & Brazel, A. J. Temporal and spatial characteristics of Arizona dust storms (1965–1980). J. Climatol. 4, 645–660 (1984).

Kok, J. F. et al. The physics of wind-blown sand and dust. Rep. Prog. Phys. 75, 106901 (2012).

Zhao X., et al. Dust aerosol impacts on the time of cloud formation in the Badain Jaran Desert area. JGR Atmos. 127, e2022JD037019 (2022).

Casquero-Vera, J. A. et al. Impact of desert dust on new particle formation events and the cloud condensation nuclei budget in dust-influenced areas. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 15795–15814 (2023).

Ardon‐Dryer, K. et al. Changes of electric field, aerosol, and wind covariance in different blowing dust days in West Texas. Aeolian Res. 54, 100762 (2022).

Lader, G. et al. Blowing dust and dust storms: one of Arizona's most underrated weather hazards, 290. NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS-WR, 94. https://www.weather.gov/media/wrh/online_publications/TMs/TM-290.pdf (2016).

Tong, D. et al. How many people were killed by windblown dust events in the United States? Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 104, E1067–E1084 (2023).

Panikkath, R. et al. Multilobar lung infiltrates after exposure to dust storm: the haboob lung syndrome. AGM 126, e5–e7 (2013).

Panikkath, R. et al. Imaging in haboob lung syndrome. SECCC 1, 24–25 (2013).

Bouet, C. et al. Impact of desert dust on air quality: what is the meaningfulness of daily PM standards in regions close to the sources? The example of southern Tunisia. Atmosphere 10, 452 (2019).

Rodriguez Ortiz, G. et al. Optical and particulate properties of dust aerosols in El Paso, Texas, Atmospheric Research, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2025.108127 (2025).

Guzman-Gonzalez, J. et al. Particulate Matter in the American Southwest: detection and analysis of dust storms using surface measurements and ground-based LIDAR. Atmosphere 15, 110 (2024).

World Health Organization. Ambient (outdoor) air pollution. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health (2022).

EPA. National ambient air quality standards (NAAQS) for PM. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/national-ambient-airquality-standards-naaqs-pm (2023).

Huang, M. et al. Toward enhanced capability for detecting and predicting dust events in the western United States: the Arizona case study. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 12595–12610 (2015).

Ardon-Dryer, K. et al. The aerosol research observation station (AEROS). Atmos. Meas. Tech. 15, 2345–2360 (2022).

Robinson, M. C. et al. The spatial and temporal impact of the February 26, 2023, dust storm on the meteorological conditions and particulate matter concentrations across New Mexico and West Texas. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 13733–13750 (2024).

Ardon-Dryer, K. & Kelley, M. C. Particle size distribution and particulate matter concentrations during synoptic and convective dust events in West Texas. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 9161–9173 (2022).

Ardon-Dryer, K. et al. Dust under the radar: rethinking how to evaluate the impacts of dust events on air quality in the United States. GeoHealth 7, e2023GH000953 (2023).

World Health Organization. WHO global air quality guidelines: particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. (World Health Organization, 2021).

Cheng, J. et al. Hourly air pollution exposure and emergency department visit for acute myocardial infarction: vulnerable populations and susceptible time window. Environ. Pollut. 288, 117806 (2021).

Lin, H. et al. Hourly peak PM2.5 concentration associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in Guangzhou, China. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 27, 333–338 (2017).

Nguyen, A. et al. Subdaily PM2.5 exposure and cardiorespiratory risks: data and findings from southern California, 2018–2020. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 17, 2431–2444 (2024).

Griffiths, S. D. et al. A study of particulate emissions during 23 major industrial fires: implications for human health. Environ. Int. 112, 310–323 (2018).

Orgill, M. M. & Sehmel, G. A. Frequency and diurnal variation of dust storms in the contiguous U.S.A. Atmos. Environ. 10, 813–825 (1976).

Deane, G. & Gutmann, M. P. Blowin’ down the road: investigating bilateral causality between dust storms and population in the Great Plains. Popul. Res. Polit. Rev. 22, 297–331 (2003).

Sprigg, W. A. et al. Regional dust storm modeling for health services: the case of valley fever. Aeolian Res. 14, 53–73 (2014).

Ardon-Dryer, K. & Aziz, T. Times matter, the impact of convective dust events on air quality in the greater Phoenix area, Arizona. GeoHealth 9, e2024GH001209 (2025).

Kok, J. F. et al. Contribution of the world’s main dust source regions to the global cycle of desert dust. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 8169–8193 (2021).

Adebiyi, A. et al. A review of coarse mineral dust in the Earth system. Aeolian Res. 60, 100849 (2023).

Roque, N. A. et al. Identifying air quality monitoring deserts in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2425310122 (2025).

Jaffe, D. A. et al. An evaluation of the U.S. EPA's correction equation for PurpleAir sensor data in smoke, dust, and wintertime urban pollution events. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 16, 1311–1322 (2023).

Kaur, K. & Kelly, K. E. Performance evaluation of the Alphasense OPC-N3 and Plantower PMS5003 sensor in measuring dust events in the Salt Lake Valley, Utah. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 16, 2455–2470 (2023).

Gautam, P. et al. Sizing accuracy of low-cost optical particle sensors under controlled laboratory conditions. Atmosphere 16, 502 (2025).

Dupont, S. et al. Performance of a low-cost optical particle counter (Alphasense OPC-N3) in estimating size-resolved dust emission flux using eddy covariance. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 18, 2183–2200 (2025).

Rodríguez, S. & López-Darias, J. Extreme Saharan dust events expand northward over the Atlantic and Europe, prompting record-breaking PM10 and PM2.5 episodes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 12031–12053 (2024).

Kok, J. F. A scaling theory for the size distribution of emitted dust aerosols suggests climate models underestimate the size of the global dust cycle. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 1016–1021 (2011).

Garcia-Carreras, L. et al. Capturing convection essential for projections of climate change in African dust emission. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 4, 44 (2021).

Pantillon, F. et al. Modeling haboob dust storms in large-scale weather and climate models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 2090–2109 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr Mary Robinson and Dr Eric Bruning for allowing to share the images. The author would also like to thank the Dust Alliance for North America (DANA-https://dust.cira.colostate.edu/) community for keeping the importance of topics related to dust events and particles.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Yuqing Dai, Anna Gannet Hallar, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editor: Alice Drinkwater. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ardon-Dryer, K. Minute-scale convective dust events are overlooked in urban air quality monitoring. Commun Earth Environ 6, 815 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02836-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02836-7