Abstract

Rock mass volume estimation is crucial for assessing landslide hazard, but it is often challenging. Seismic ambient noise data and polarisation analysis can be used to identify the eigenfrequencies of the blocks, which are in turn related to their volume. The aim of this work is to propose a procedure to build an eigenfrequency-volume abacus to estimate the order of magnitude of blocks’ volumes from the extracted resonance frequencies independently estimating the blocks’ area. The resonance frequency is extracted from seismic noise measurements analysed using the Horizontal-to-Vertical Spectral Ratio technique. The abacus is developed here by means of numerical simulations and field data, acquired over lateral spreads and block slides on Malta Island, where independent direct estimates of the blocks’ volume are available. These were used to validate the proposed methodology in two test sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The natural frequency (f0) of an object is the frequency at which it tends to vibrate when it is disturbed from its rest position and allowed to oscillate freely, without any external or continuous force acting on it1. At this frequency, the system oscillates with maximum amplitude, assuming minimal damping. If a periodic external force matches this frequency, the system may experience resonance, where the amplitude of vibration can grow significantly.

In geophysics and engineering geology, natural frequency refers to the fundamental or higher-order modes of vibration of materials, rock masses, soil layers, or entire slopes2. Natural frequency and resonance phenomena are critical tools in the field of geosciences, making it possible to investigate the mechanical behaviour, stability, and seismic response of rock masses. A variety of studies have explored these concepts across contexts such as rock mass stability, slope resonance, sedimentary basin amplification, and material characterisation, using both experimental and numerical approaches. Slope stability under seismic excitation has been examined by different authors, and several studies based on natural frequency have focused on the stability analysis of rock masses, demonstrating their effectiveness (e.g.3,4,5,6,7,8). For example, Häusler et al.6 demonstrated that frequency domain decomposition modal analysis could effectively detect resonance modes of unstable rock slopes. Changes in the natural frequency of rock masses have also been linked to the discontinuity network. Studies have shown that as a rock mass experiences increased fracturing or damage, its stiffness decreases, leading to a corresponding drop in its natural frequency5. In the last-mentioned paper, the authors found a direct correlation between reduced natural frequency and decreasing stability, suggesting that resonance monitoring could provide early warning for potential rockfalls or landslides.

Beyond rock mechanics, the concept of resonance plays an important role in seismic soil behaviour. Some studies have explored vibro-compaction methods, where the efficiency of soil densification improves when the operating frequency of the compactor matches the soil’s natural frequency9. As far as engineering applications, the natural frequency of a building, which refers to the specific frequency at which the structure tends to oscillate when disturbed by dynamic forces, is considered both during seismic design and in structural health monitoring10. The modelling or estimation of natural frequencies of buildings is, in fact, essential to avoid resonance conditions by altering mass, stiffness, shape and volume, or incorporating damping mechanisms such as base isolators or tuned mass dampers.

Originally, the Horizontal-to-Vertical Spectral Ratio technique11, commonly referred to as HVSR or H/V method, was developed to obtain, from seismic noise measurements, the resonance frequency of sedimentary layers overlying a seismic bedrock (i.e. a layer characterised by a high shear wave velocity). The study of ground resonances (or vibration modes, or natural frequencies) is usually considered with the simplifying assumption of plane-parallel stratigraphy (i.e. a 1-D approximation). As a consequence, in the simplest case of horizontal sedimentary layer capping a bedrock half-space, the 1-D resonance frequency is inversely related to the local bedrock depth, as a function of the shear wave velocity of the sediment layer12. Therefore, if the 1-D approximation is not fully valid, spatial variations in the natural frequency will reflect changes in the bedrock depth (still assuming lateral homogeneity of the sedimentary cover). However, 1-D approximation is no longer valid in peculiar geological settings like fluvial or glacial valleys (e.g.13,14) or basins (e.g.15,16). In contrast to the 1-D case, 2-D resonance can no longer be related to the local stratigraphy below the measurement site but rather depends on the geometry and mechanical properties of the 2-D target12,17. A comprehensive review of the application of 2-D resonance for subsurface investigations and stratigraphic imaging, both for shallow and deep applications, is provided by ref. 16 and references therein.

The SESAME (Site EffectS assessment using AMbient Excitations) project18 attempted to standardise the HVSR method in terms of acquisition and analysis procedures. In addition, several acquisition, processing, and interpretation options are available for this technique. Within the COSMOS International Guidelines on Applying Non-Invasive Geophysical Methods for Characterising Seismic Site Conditions initiative, Molnar et al.19 summarised the state of the art on the technique towards international guidelines and recently20 updated their review.

The simplest model proposed in literature to calculate the natural or fundamental resonance frequency f0 of a rock assimilates the rock to a single-degree-of-freedom block and the rock-slope connection to a tension-compression spring5. Thus, f0 is a function of the physical properties of the block and is expressed as (e.g.5):

where k is the equivalent stiffness of a spring and M is the mass of the object. Equation 1 considers an object which is free to vibrate only in the vertical plane. However, along with the vertical vibration, an object can also perform swaying or rotational vibrations, which make the calculations more complex, but the basic physical principles remain the same. Equation 1 or similar relations that link the natural frequency to other mechanical parameters of the object are frequently used to derive the mechanical parameters from the measured (or modelled) natural frequency by fixing the mass as a constant. Alternatively, Eq. 1 can be used to estimate the natural frequency of an object with a fixed mass based on its measured or estimated mechanical parameters.

This study takes a different approach. The main objective of this study is to estimate the mass (or volume) of rock blocks using the frequency fHV estimated from H/V passive seismic geophysical measurements21 as a good approximation/estimator of f0 (the block eigenfrequency). In fact, as reported in literature by several authors (e.g.21,22,23,24,25), from seismic noise data it is possible to identify frequencies that are linked to the volume of blocks (normal-mode vibrations) rather than to a stratigraphic resonance effect. These frequencies are the eigenfrequencies of the block and could or could not (if the vertical component is amplified) be visible as peaks in the H/V curve, but are always characterised by a strong polarisation normal to the dominant fracture network and by a strong linearity of the ellipticity21,25. It is worth highlighting that, as proposed by Burjánek et al.26,27, the time-frequency polarisation analysis allows to describe the ground particle motion by means of a 3D ellipse defined, for each frequency, by three parameters, namely: the strike (the semi-major axis azimuth), the dip (the semi-major axis inclination with respect to the horizontal plane), and the ellipticity (the ratio between the semi-minor and semi-major axes that ranges between 0 - purely linear motion - and 1 - purely circular motion).

The step forward presented in this work is thus the definition of an eigenfrequency-volume relation: assuming that the H/V curves also contain information about the eigenfrequencies of a deforming rock mass, once these frequencies are identified, an ad hoc-developed abacus, obtained by fixing certain mechanical and geometric parameters, which vary for each specific geological background, can be employed to obtain a first approximation of the order of magnitude of the block’s volume. Some numerical simulations were carried out to construct this abacus, and it was validated by means of real field datasets. The results of both the simulations and the field data analysis are presented in Section ‘Results’ and are deeply discussed in Section ‘Discussion: how to use the block’s volume abacus’, where the proposed procedure is also detailed. The work’s conclusions are illustrated in Section ‘Conclusions’, while the method implementation is described in Section ‘Methods’.

For the sake of completeness and clarity, it is necessary to recall some basic concepts and define the symbols that are used in the following. In particular, in this manuscript:

-

f0 is the eigenfrequency of a freely oscillating object, also called natural frequency. In geophysics and engineering geology, this frequency is usually referred to as the fundamental and/or the resonance frequency;

-

fW, fL, and fZ are the three frequencies along the three dimensions of the block, following the two horizontal dimensions W and L, and the vertical one Z, respectively. Usually, the lowest between fW and fL is taken as the f0;

-

fij is the eigenfrequency of the flexion mode ij, with i and j being the numbers of vibration antinodes, for a block assimilable to a plate. The fundamental eigenfrequency f0 corresponds to f11;

-

fHV is the frequency derived from experimental H/V curve(s) and polarisation analysis and selected to enter the abacus (see Section ‘Conclusions’). It is considered to be a good approximation/estimator of f0.

Results

In this section, the results of both the simulations and the field survey measurements are presented. In particular, the simulations’ results permitted building an ad hoc abacus that can be used to estimate the order of magnitude of the blocks’ volume starting from field seismic noise measurements (see Section ‘Discussion: how to use the block’s volume abacus’ for details about the implementation of the proposed procedure).

Abacus to estimate the volume of a block

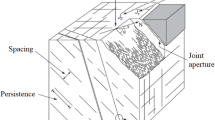

Blocks with small geometric ratios W/Z2, being W the smallest horizontal dimension (i.e. the thickness against which bending occurs) and Z the height of the block, can be approximated to an Euler–Bernoulli cantilever with rectangular cross section, as they share similar boundary conditions (i.e. in both cases the structures are rigidly fixed at their base and free at the other side). Their fundamental frequency f0 can be obtained analytically as described by Chopra10:

with E being the Young’s modulus, ρ the density. This simplified model has been shown to adequately reproduce the measured natural frequencies of features such as rock towers and crests28,29,30,31. Nevertheless, the eigenfrequency of rock slices, originating from a cliff that delaminates along vertical planes, cannot be directly obtained by Eq. 2, even though these rock slices are characterised by a small geometric ratio W/Z2, being the thickness two or three orders of magnitude lower than the other two dimensions22. These rock slices can be rather assimilated to a plate, and thus the eigenfrequency of the flexion mode ij, with i and j the numbers of vibration antinodes, according to Got et al.22, can be calculated with Eq. 3:

where W is the thickness (i.e. the smallest horizontal dimension, similarly to Eq. 2), L the other horizontal dimension, Z the height of the block, E the Young’s modulus, ρ the density, and ν the Poisson coefficient.

In the majority of real cases, the eigenfrequency of a block cannot be obtained by means of analytical equations but requires specific numerical simulations. Numerical simulations based on the Finite Element Method (FEM) were thus performed to determine the natural resonance frequencies of homogeneous rock blocks with defined dimensions and material properties (see Section ‘Methods’ for the assumptions made and the parameters used). These simulations encompassed a modal analysis, computing the block’s natural frequencies and associated mode shapes in the absence of external excitations. The obtained results provide a first-order approximation of the vibrational behaviour of rock materials, which can assist in inferring their expected resonance frequencies based on their physical properties and geometry.

Figure 1 compares the fundamental frequencies f0 (i.e. the lowest between fW and fL as defined above) obtained from FEM simulations with those predicted by the Euler–Bernoulli and Timoshenko–Ehrenfest beam theories. Timoshenko beam theory refines Euler–Bernoulli theory by relaxing the assumption that plane cross-sections remain perpendicular to the neutral axis during bending by incorporating the effects of shear deformation and rotary inertia, which become significant in short, thick, or high-frequency vibrating beams. The theoretical cantilever behaviour, shown by the red line in Fig. 1, is similar to the one reported from previous studies in literature28,29,30,31. At higher geometric ratios, where the assumptions of the Euler–Bernoulli beam theory are no longer valid, the simulation results (coloured dots in Fig. 1) exhibit a sublinear trend, in agreement with the predictions (orange crosses in Fig. 1) of Timoshenko–Ehrenfest beam theory approximation32,33,34,35. Nevertheless, the simulated fundamental frequencies (coloured dots) are consistently lower than the theoretical values (orange crosses). These results suggest that, for certain geometries, all the dimensions of the block contribute to the definition of its natural resonance frequency (see for more details Section ‘Discussion: how to use the block’s volume abacus’).

Each circle represents a block with unique geometric dimensions but identical rock properties (see Section ‘Methods’). The colour of circles indicates the block height. The red line shows the analytical trend predicted by the Euler–Bernoulli beam theory for a cantilever with a rectangular cross section, while the orange crosses show the predicted values considering the Timoshenko–Ehrenfest approximation. The shape of three exemplary blocks, representative of specific simulated scenarios, is reported.

Calculating the regression curves of the simulated data, it is possible to build the eigenfrequency-volume abacus. Figure 2a, b summarises in linear and logarithmic scales, respectively, all the simulation results. In these abacuses, the vertical axis is the average of horizontal fundamental frequencies, and the black and teal curves were obtained as regressions of the results of the numerical simulations (grey dots). The black curves represent the trend of the average of the horizontal fundamental frequencies (vertical axis) as a function of the volume (horizontal axis), for a fixed surface area identified by the black number on top of the corresponding curve. Similarly, the teal curves represent the same trend for different heights, identified by the teal numbers on the right side. The dashed portions of the previous curves represent the behaviour extrapolated from the simulations. As these trends are obtained through a regression analysis, the values obtained from the intersection of the different trends may not correspond to the actual volumes. Furthermore, considering the inherent simplifications within the numerical models, the results may not coincide with the actual volumes or frequencies of real blocks, but they provide a valuable approximation of the order of magnitude of the blocks’ volume, useful for preliminary assessments and comparisons.

a Linear and b logarithmic scale of the eigenfrequency-volume abacus. The trend of the average of the horizontal fundamental frequency is shown as a function of the volume, given a fixed surface area (black curves) or a fixed height (teal curves). The grey dots represent the simulation results (see Section ‘Vibration modal analysis of a single block constrained at the base’ for the parameters employed in the simulations) used for the regression. The dashed lines represent the extrapolated trends.

The experimental dataset

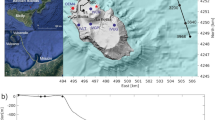

To validate the applicability of the abacuses, two real datasets of seismic noise measurements were collected at two sites on Malta Island: the Il-Prajjet - Anchor Bay (Fig. 3a), and Il-Qarraba peninsula (Fig. 4a). For a detailed description of the two test sites, please refer to Section ‘Test sites’. The HVSR curves are plotted for both sites in Fig. 3b and Fig. 4b, respectively, while the ellipticity and strike polar plots are shown in Figs. 3a and 4a. It is possible to observe that, in both sites, the H/V peaks in the range of 1–2 Hz always have the same characteristics in terms of H/V amplitude, polarisation, and ellipticity. In particular, they sometimes present a polarisation, but their ellipticity is always in the range 0.2–0.4 that is typical for hard-rock sites7,21,23,24,36. According to literature, e.g.23,24,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,37,38,39,40, these picks can be attributed to the local stratigraphy (a four-layer limestone and clay sedimentary sequence, see Section ‘Methods’).

a Location of the measures collected at Il-Prajjet (north-east sector of Anchor Bay, Malta Island) [Photograph credit: Stefano Devoto (Units)]. For each measure, the ellipticity and the strike polar plot are shown. Cyan dots indicate the location of measurements acquired during the 2011–2012 campaigns, while yellow dots indicate the site of measurements acquired during the 2023 campaign (see Section ‘Test sites’). The map on the left indicates the location of the study area (red rectangle), as well as all the other data available from literature on Malta Island. b H/V curves of each acquisition.

a Location of the measures collected at Il-Qarraba peninsula (Malta Island) [Photograph credit: Stefano Devoto (Units)]. For each measure, the ellipticity and the strike polar plot are shown. Cyan dots indicate the location of measurements acquired during the 2011–2012 campaigns, while yellow dots indicate the site of measurements acquired during the 2023 campaign (see Section ‘Test sites’). The map on the left indicates the location of the study area (red rectangle), as well as all the other data available from literature on Malta Island. b H/V curves of each acquisition.

Some curves show a peak that spans a frequency range of about 7–8 Hz (i.e. from about 4 Hz up to 12 Hz). In this range, the frequencies are polarised, and the ellipticity drops to zero. As the geological setting is similar for all the acquisitions, also the topographic amplification is expected to be the same. Nevertheless, because these peaks are clearly different from one measure to the other, they are considered to be related to the volume of the blocks, which are supposed to be single vibrating objects7,21,23,24,36. As an example, it can be seen that the POP1 measure (red curve in Fig. 3b with a peak at 11 Hz) was acquired over a block with an estimated volume of about 130 m−3 (this volume was obtained during the 2011–2012 field survey and is reported in ref. 41), while the POP3 measure (light brown curve in Fig. 3b with a peak at 8.5 Hz) was acquired over a larger block, with an estimated volume of about 1200 m−3 (block VI in ref. 41). At the same time, the POP14 measure is flat in the range 4–12 Hz, and it was acquired far from the fractured zone, in an area not affected by gravity-induced fractures and thus assumed to be characterised by an infinite volume. Three measures (POP6, MAL2, and MAL7) show evidence of polarisation along a specific direction but their ellipticity is more or less flat around a constant value, and thus a specific range of frequencies cannot be identified. A similar behaviour is reported in ref. 24.

Table 1 lists the estimated dimensions (W, L, and Z) derived from both field observations and Uncrewed Aerial Vehicle Digital Photogrammetry (UAV-DP) of all the blocks located at Il-Prajjet (north-east sector of Anchor Bay) and at Il-Qarraba, their approximated areas and volumes, the order of magnitude of the volumes calculated, and the frequencies selected from the H/V data (fHV). Figure 5 shows the relation between the calculated order of magnitude of the volumes of each block and the fHV values identified from the H/V curves and the polarisation analysis.

Discussion: how to use the block’s volume abacus

Estimating the volume of rock masses is fundamental for assessing landslide hazard in areas prone to detachment, but it is challenging. This is related to the internal structure and geomorphic conditions of rock slopes42,43,44,45. The orientation and properties of discontinuities play a fundamental role, and it has been shown that rock blocks’ volume could be underestimated if joints are erroneously assumed to be persistent46. Unfortunately, in common practice, it is not easy to define the blocks’ volume because it is quite hard to estimate the height of a block: non-open discontinuities, in fact, affect the portion of the block that can freely vibrate, influencing the height that has to be considered in the actual volume estimation. Thus, we proposed a procedure to estimate the volume of a block by measuring its natural frequency by means of seismic noise.

A recent study47 investigated the vibration characteristics of rock samples under an external excitation source to understand the rock failure mechanisms under dynamic loading (e.g. during petroleum drilling, blasting or rock fragmentation), and it highlighted that the resonance frequency observed in the excitation experiment must be distinguished from the natural frequency of rock masses. In particular, in these experiments, the resonance peaks with high-frequency excitation are the way to visualise the natural frequencies of rock samples on a laboratory scale. The above-mentioned work concluded that, if the sample dimensions varied linearly (i.e. the geometric shape is constant), the natural frequencies of the two samples are also proportional. In particular, if sample 2 is twice the size of sample 1, its natural frequency will be half that of sample 1. This outcome is confirmed by the results of the simulations carried out in this work and summarised in Table 2 for some selected blocks. The first three columns of Table 2 list the three dimensions (the two horizontal W and L, and the vertical one, Z), whereas the last three list the associated natural frequencies. It should be noted that fW and fL are the two horizontal frequencies averaged to obtain the vertical axis of Fig. 2. The same results, as expected, also show that fZ (the frequency along the vertical direction) is inversely proportional to the height of the block.

The numerical simulations carried out in the framework of the present work have also shown that keeping constant the Poisson ratio and changing the other physical properties/parameters (like the density ρ, the P-waves velocity Vp, the Young’s modulus E), it can be observed that:

• if the block’s dimensions are kept constant (see Fig. 6a), the natural frequencies fW, fL, and fz are linear with the P-waves velocity (Vp), regardless of the material density (ρ), and thus, scales with the square root of the Young’s modulus (E), being:

Simulated fundamental frequency along the horizontal (a, b), and vertical (c) components, respectively, as a function of the shear-wave velocity: the colour of the marker represents the height of the simulated block. d Variation of the mean of the horizontal fundamental frequencies as a function of height: the colour of the marker represents the volume of the simulated blocks, and the symbols represent their horizontal shape factor (L/W).

• if the block’s height (Z) is kept constant, the greater the two horizontal dimensions W and L (i.e., a larger area A for the same height means that the block is more similar to a slab than to a beam/tower) the higher the average of fW and fL, as visible from the abacus (Fig. 2) following a selected teal curve;

• if the block’s volume (V) is constant, the average of fW and fL is more variable for lower Z values, i.e. the shape factor L/W has a higher influence on the horizontal frequencies for stocky blocks (see Fig. 6b).

All the previous considerations can be summarised as follows: given a specific site, the expected block’s natural frequency f0 (being f0 the lowest values between fW and fL, as described at the end of the Introduction) is inversely proportional to the block’s volume, with f0 tending to zero for blocks of infinite size or not affected by landsliding (i.e. a stable area in mountainous sites or a plateau without blocks located on the edge of the cliffs).

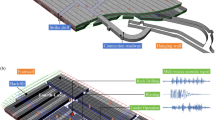

In the field, it is hard to evaluate f0, while, as already shown by some works21,22,23,24,25 and said in the Introduction, it is easier to estimate the block natural frequency by the H/V curves (fHV). Thus, a procedure to estimate the volume of a block from the results of the H/V curves is proposed and summarised in Fig. 7. The assumption at the basis of this workflow is that the study area/blocks should be assumed homogeneous from a geological point of view, i.e. each block differs from the others only in terms of its dimensions.

The 6 steps of the proposed procedure are shown: Step 1: select the study area and acquire seismic noise data; Step 2: analyse data to obtain H/V curves, spectra of the three components, particle motion, directivity, and polarisation analysis; Step 3: integrate results and identify the different frequencies; Step 4: estimate the area (A) of the block; Step 5: enter the abacus with values of Step 3 and Step 4; Step 6: estimate the volume. Photograph credit: Stefano Devoto (Units).

The procedure to use the eigenfrequency-volume abacus shown in Fig. 7 is the following:

-

1.

Given a study area, seismic noise measurements have to be collected on different blocks characterised by different dimensions. When possible, measurements should also be taken on unfractured/stable plateaus/areas near the blocks, in the part not yet affected by landsliding;

-

2.

The H/V curve, the spectra of all three components, the particle motion, the directivity and the polarisation analyses must then be calculated for all the acquired data;

-

3.

The integrated results of these analyses must be evaluated to identify the frequencies linked to the regional stratigraphy, those to other effects (e.g. sea, wind, anthropic noise, topographic amplification), and those of interest related to the blocks (fHV);

-

4.

For each block, the two horizontal dimensions W and L should be estimated by the outcomes of field measurements, GIS, aerial/satellite images, or UAV-DP, then calculating the area (A) of the block;

-

5.

Having the information from steps 3 and 4, it is possible to enter from the vertical axis in the eigenfrequency-volume abacus (Fig. 2) with the values of fHV reaching the black curve corresponding to the estimated A value;

-

6.

It is possible to estimate Z from the teal curve in Fig. 2 that intersects the black curve, and thus to estimate the order of magnitude of the block’s volume V (horizontal axis).

The procedure’s step that allows to identify different typologies of H/V peaks is not trivial or straightforward and must comply with various criteria, including the analysis of the shape of the spectra of the three components, as well as that of the results of the polarisation analysis.

Even if this topic is out of the aim of the present work, and it will not be explored in depth, hereafter the two main criteria used to select the fHV are summarised; the reader can refer to the related literature for a more detailed explanation and discussion (e.g.12,16,18,21,26,27,37). First of all, the spectrum of the vertical component is considered: in correspondence of the fHV it has to follow the other two horizontal components (and thus, no peaks are present in the H/V curve) or at least it has to be flat (and thus, a peak with a small amplitude is observed in the H/V curve), but the vertical spectrum has not to show the characteristic eye-shaped behaviour of stratigraphic peaks (see for example23,37). Once frequencies with the above-mentioned characteristics are identified, their directivity/strike and their ellipticity are analysed selecting those frequencies with a strong polarisation and a strong linearity of the ellipticity (see for example21,23,26,27).

The procedure to use the eigenfrequency-volume abacus was validated in two test sites, where the geological, the geomorphological, and the structural setting is well-known (see Section ‘Test sites’) and where, as described in ref. 41, independent measures of the blocks’ volumes and areas are available from field measurements, direct observations, photogrammetry, and feature analysis using satellite images and the outcomes of UAV-DP technique. In particular, for each seismic noise measure a fHV value (as summarised in Table 1) was selected on the basis of the strike and of the ellipticity, and the volume of the block was retrieved from the eigenfrequency-volume abacus knowing the block’s area from available independent data. The value obtained from the abacus was then compared with that calculated by means of the independent measures available41.

Figure 8a shows the H/V curves of five selected acquisitions from the two test sites (POP1, POP3, and POP10 recorded at Il-Prajjet; MAL1 and MAL3 recorded at Il-Qarraba). For each acquisition, the value of the blocks’ area (A) is indicated below the name of the acquisition. Panel b of Fig. 8 shows an example of how to use the abacus (Fig. 2) to estimate the blocks’ volume. In particular, for the five considered blocks, the horizontal lines indicate the fHV derived from the H/V curves, while the vertical lines indicate the estimated volumes. Table 3 summarises the frequencies selected from the H/V data (fHV), the order of magnitude of the block volumes estimated from the abacus, and the block volumes from independent field observations and UAV-DP, as well as the order of magnitude for all the blocks at Il-Prajjet and at Il-Qarraba peninsula.

a Five selected H/V curves, three of them (POP1, POP3, and POP10) acquired at Il-Prajjet (north-east sector of Anchor Bay) and two of them (MAL1 and MAL3) at Il-Qarraba peninsula. For each acquisition, the value of the area (A) used in panel b is indicated. b The eigenfrequency-volume abacus. b Coloured lines refer to the measures in (a).

As said in Section ‘The experimental dataset’, some of the H/V peaks (specifically those in the 1–2 Hz range), as expected by the literature, are present in the whole dataset: they are roughly constant in terms of frequency and amplitude, they sometimes present a polarisation, but their ellipticity is in the range 0.2–0.4, that is typical for hard-rock sites7,21,23,24,36 and frequencies linked to the geological stratigraphy. As reported in refs. 48,49 in fact, all the three upper layers at Malta Island (i.e. the UCL: Upper Coralline Limestone, BC: Blue Clay, GL: Globigerina Limestone, see Section ‘Test sites’) play an important role in perturbing the ground motion in the frequency range 1–2 Hz (i.e. the fundamental frequency of the sites). This result is confirmed by the analytical H/V analyses (shown in Fig. 9), carried out in the framework of this work after Garcia-Suarez et al.50, for a laterally homogeneous medium (over an infinite half-space) characterised by the following four-layers sequence: UCL: Upper Coralline Limestone, BC: Blue Clay, GL: Globigerina Limestone, LCL: Lower Coralline Limestone48,51. The different curves show the theoretical HVSR for various thicknesses of the topmost layer (consisting of the UCL layer plus the height of a block). The values of the geophysical and geotechnical parameters (i.e. the shear-wave velocity Vs, the layer’s thickness h, and the density ρ) of each formation have been retrieved from literature29,40,48. This H/V analysis shows the fundamental frequency (the lowest one) together with the upper ones, which indeed are not visible on an acquired H/V curve but can be observed in the seismic site response analysis available in literature (e.g.48).

The different curves show the theoretical HVSR for various thicknesses of the topmost layer (consisting of the UCL layer plus the height of a block). Vs (shear-waves velocity), h (layer’s thickness), and ρ (density) values have been retrieved from literature (in particular29,40,48). UCL: Upper Coralline Limestone, BC: Blue Clay, GL: Globigerina Limestone, LCL: Lower Coralline Limestone48,51.

Conversely, some other peaks (specifically those at intermediate frequencies) were not always present in the recorded data. They span a frequency range of about 7–8 Hz, they are polarised, and the ellipticity at those frequencies drops to zero, as expected for the eigenvalues of blocks7,21,23,24,36.

As said, this behaviour is known in literature: for example, in Panzera et al.37, the authors assess that H/V peaks around 1.5 Hz are associated with a geological interface, while other higher frequencies peaks, not visible in the unfractured region, may be associated with the presence of fractures and of blocks almost detached from the cliff and therefore free to oscillate. Galea et al.23 comment that on the plateau the H/V graphs show only the peak at around 1.5 Hz that can be attributed to the local stratigraphy according to other previous studies37,38,39, while measurements acquired moving toward the cliff show a more complex resonance behaviour associated with particular polarisation directions. In Iannucci et al.25, the observed behaviour of rock blocks can be related to a proper inertial vibrational (volume-controlled) effect driven by the kinematic junctions and dimensions, rather than to a proper resonance (depth-controlled) effect. Moreover, the eigenfrequencies are directly proportional to the block stiffness and inversely proportional to its size. This last concept is also described in Galea et al.23 who assess that the resonance frequencies observed on the Swiss Alps are lower than those observed on Malta Island, probably because of the larger dimensions of the unstable landforms in the Alps. All the authors agree that the polarisation analysis allows for an unambiguous distinction between H/V peaks related to the geological layering and higher frequency peaks related to the mechanical behaviour and geometries of detached blocks. Table 4 summarises the results of the seismic noise analyses carried out on Malta Island in the framework of all the cited works, specifically23,24,25,37,38,39,40,49.

To further validate the proposed procedure, the abacus has been employed to estimate the order of magnitude of the block mentioned in Iannucci et al.24 and located on the East coast on the same formation but characterised by a different geological facies. The reported block dimensions are: W = 8.5 m, L = 100.0 m, Z = 30.0 m, while the frequency obtained by experimental seismic noise data is fHV = 3.3 Hz24. Thus, Vcalc is 25,500 m−3. From the abacus built for a ρ = 2146 kg m−3 (values obtained by ref. 24), the Vabacus is of the order of 2 × 104 m−3, so perfectly in agreement with ref. 24 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

The proposed procedure has some inherent limitations.

First of all, if the stratigraphy of the study area is not known, or it is very complex and inhomogeneous, or it is not possible to highlight volume-controlled frequencies, i.e. the eigenfrequencies of the deforming rock mass, the proposed procedure cannot be applied.

Secondly, the selection of the correct fHV is essential to the practical application of the proposed method, because an incorrect selection of this frequency would result in an incorrect volume estimate. Nevertheless, an error of 1−2 Hz in the estimation of fHV does not significantly affect the estimation of the volume’s magnitude order.

Thirdly, the eigenfrequency-volume abacus was built based on specific geophysical and rheological parameters, thus, it cannot be applied in sites where these characteristics are very different. A different abacus must be implemented, considering different geophysical and rheological parameters in the modelling.

On the other hand, the main advantages of the proposed abacus are that seismic noise measures can be performed quite easily and that the two horizontal dimensions of the blocks can often be straightforwardly estimated by outcomes of UAV-DP or satellite-image interpretation. Moreover, it is important to highlight that some deviations between the data calculated with the proposed geophysical method (the abacus) and the field-derived measurements may be linked to a different persistence of the fracturing than expected/considered. The presence of discontinuities, in fact, affects the shear-wave velocity. Moreover, tests performed on datasets recorded on the same block: in different years and seasons; in different locations at the same time; in the same location at different times, all provided comparable H/V curves, at least within the frequency range used for estimating the block’s volume (see Supplementary Fig. 3). This demonstrates the robustness of the proposed procedure, which is almost unaffected by possible seasonal and local effects on seismic noise data. Thus, the proposed procedure has a potentially valuable application, particularly in the context of unstable rock cliffs where it is possible to have a good estimation of the cliff height and thus of the blocks’ volume (Vcalc).

At the beginning of this section, it was remarked that the aperture values of the fractures play a fundamental role in controlling the block’s volume prone to falling. Thus, if some seismic noise measures are acquired over a rock cliff and the volumes estimated (Vest) applying the abacus are different from Vcalc, this means that the aperture and persistence values of the visible discontinuities are different from expected. In particular, if Vest is lower than Vcalc, it means that the fractures are less persistent and partially isolate the blocks, differently from field-derived observations. On the contrary, if Vest is higher than Vcalc, it means that the discontinuities are more persistent than they seem, possibly completely isolating the analysed block from the surrounding rock masses. An example of this could be seen at Il-Qarraba site: MAL7 and MAL8 were acquired over the same block but on two different sides of a fracture. From the polarisation analysis, it seems that MAL8 has a fHV around 20 Hz, with a strike orthogonal to that of MAL7, meaning that MAL7 and MAL8 were actually acquired over two different blocks.

Conclusions

The rationale behind this work is that some peaks of the H/V curves acquired over rock blocks characterised by homogeneous materials are not linked to the geological regional stratigraphy of the site, but rather to the volume of the blocks themselves. Thus, the fHV has been considered as a proxy of the block natural frequency f0, and a procedure to estimate the blocks’ volume from the H/V curves has been developed. Synthetic and field data collected at two different sites demonstrated the effectiveness of the proposed procedure. This makes it possible to obtain an estimate of the block’s volume, despite some constraints being noted and discussed. Future research will extend the field examples to consider different geological backgrounds, lithologies and geometries.

Methods

Vibration modal analysis of a single block constrained at the base

Vibration modal analysis allows the identification of the dynamic properties of n- degree-of- freedom linear dynamic systems, i.e. their natural frequencies, mode shapes, and damping factors. It is formalised through an eigenvalue system whose eigenvalues ωi and eigenvectors ϕi correspond to the system’s natural frequencies and mode shapes, respectively.

In the context of the FEM, the system can be discretised and the generalised equation of motion for the system written as:

where M, C, and K represent the mass, the damping, and the stiffness matrices, respectively; U is the displacement vector, and its time derivatives are represented using the dot notation; F is the loading force vector. In vibrational modal analysis, the damping matrix is often omitted because damping is typically small, highly system-dependent, and not a fundamental property of the structure in the same way that mass and stiffness are. Its exclusion simplifies the eigenvalue problem, which stays linear in \({\omega }^{2}\), allowing natural frequencies and mode shapes to be computed directly. When needed, damping can be later introduced empirically. Furthermore, in this study, following Clough et al.1, no loading force has been assumed to act on the system, because the modal analysis focuses on the inherent modes of vibration, which are independent of external loads. It has been assumed that the blocks are rectangular cuboids with different aspect ratios for their horizontal dimensions, as well as being of multiple heights.

The block has been discretised using tetrahedral meshes (with the software Gmsh52) with a maximum element size equal to 1/15 of its shortest dimension. In all simulations, the block has been constrained at its base using a fixed boundary condition, i.e. all the available degrees of freedom for the nodes defining the bottom surface have been locked. This is quite realistic for the test sites, as the blocks are separated from each other laterally by persistent fractures, while at their base, they are locked (and sometimes sunk) by BC formation [Mantovani et al.53]. The properties of the materials have been selected from available estimates in literature24,25,38,39,48,49, and considering that, from area to area, the UCL exhibits many facies and thus elastic properties vary according to the state of the fractures39. In particular, to build the abacus to estimate the volume in the study areas, the Young modulus is set to E = 3.04 GPa, the density is set to ρ = 1900 kg m−3, and the Poisson ratio is fixed to ν = 0.25. These parameters correspond to a S-wave velocity of about VS ≈ 850 m s−1 in agreement with Vella et al.39 and Farrugia et al.40,48. On the contrary, as said previously in the text, to build the abacus to estimate the volume of the block studied by ref. 24, the UCL density is set to ρ = 2146 kg m−3 while the VS and the Poisson ratio are kept equal. These two abacuses, together with a third one created using ρ = 2146 kg m−3 and VS ≈ 400 m s−1, are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2 and allow for evaluating the influence of VS and ρ on the eigenfrequencies-volume abacus.

The selection of a homogeneous composition and fixed boundary conditions represents key model assumptions made to simplify the analysis of the results while making them more general. It is quite obvious that in reality the composition is never actually homogeneous, even at a very local scale, thus possibly producing inaccuracies in the parametrisation. However, a constant value can usually be considered a good enough approximation at least for order-of-magnitude estimates, as in the present case. That being said, the study of specific blocks, especially contiguous ones, may require different boundary conditions, as these may have a major influence on the results of the simulations.

The frequencies associated with the lowest translational mode along each of the 3 main axes of the block (i.e. the mode with the lowest frequency with displacement along a specific axis) have been extracted from the results of the simulation (performed using the software CalculiX54). In Fig. 10, the corresponding mode shapes are shown for a block of size L = 43 m, W = 10 m, Z = 14 m. The selection of the modes has been performed considering their ratio of effective mass Meff,i, i.e. the ratio of the effective mass participating in the mode and the total effective mass. The effective mass of the block is, in turn, computed as the squared value of the corresponding participation factor \({\gamma }_{i}={\phi }_{i}^{T}{MD}\), where D is the excitation direction vector. The participation factor measures the extent to which each mode contributes to the response of a structure in a given direction, i.e. how strongly a mode couples with a rigid-body translation. The effective mass quantifies this coupling as the fraction of the total mass that is excited by a specific mode. The lowest transitional mode in a direction is identified, therefore, as the lowest frequency mode f0 with a dominant effective mass in that direction.

Test sites

Seismic noise datasets were acquired along the northwestern coast of Malta Island (central Mediterranean Sea) at two distinct test sites (Figs. 3a and 4a). Three different campaigns were performed, one in 2011, one in 2012, and one in 2023, to ensure that the measures are independent of seasonal and time effects, and that measures collected on the same block in different locations are comparable. In the Supplementary Fig. 3 are shown some of these repeated data, e.g. same place but different time, or same block, but different place and time, or same block and time, but different place.

The first site (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 4) is located in the inner portion of Anchor Bay (Il-Prajjet), a narrow structural cove51. In particular, seismic noise data acquisition was performed along the edge of a karst plateau made up of UCL Formation and on the top of different sizes displaced blocks located at the side of the plateau. The latter is bounded by an E-W oriented steep cliff. The external margin of this plateau is intensely fractured due to the presence of an extensive lateral spreading phenomenon51,53,55. This type of slow-moving landslide is caused by the contemporary presence of resistant UCL rocks and underlying clays terrains (BC), which form gentle slopes at the base of the plateau. Lateral spreading phenomenon generated a spectacular 109-m-long discontinuity41, that partially isolates, enlarges, and lowers a 43,500 m−3 slab (POP13 in this study) along the edge of the plateau41,53. Long-term GPS monitoring indicates that this lateral spread is progressively evolving into a block sliding53,55. The presence of this block sliding mechanism is evident at the base of the plateau, where six huge blocks (for details41) are extremely slowly moving towards an amusement park, named Popeye Village.

The second test site (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 5) is Il-Qarraba peninsula, located 3.7 km south of Anchor Bay and represents one of the main landmarks of the Island of Malta. It is a head-shaped promontory connected to the mainland by a narrow isthmus composed of over-consolidated clays and marls belonging to the BC Formation. A UCL butte rises in the middle of the peninsula, reaching an altitude of 43 m, and caps BC hummocky slopes that extend down to the shorelines. This butte is bordered by 11 m high cliffs and is intensely cracked by a complex network of discontinuities on its western and northern flanks41. Other persistent discontinuities crack UCL rocks in the central part of the butte, witnessing an advanced stage of lateral spreading41. As in Il-Prajjet, recent research activities carried out using outputs of long-term GPS surveys have revealed that this lateral spread is evolving into multiple block slides55, mainly affecting the north and west portions of the peninsula51. These block slides are transporting thousands of massive UCL blocks seawards, producing a distinctive coastline morphology categorised as Rdum coast by ref. 56. Seismic noise data were acquired on the flat surface of the butte in 2011–2012, and in 2023 on the uphill-facing blocks transported from block slides and located at the base of the cliff that limits the western part of the butte (Fig. 3c).

Instruments and software

To acquire seismic noise data, the same all-in-one compact three-components sensor developed by MoHo s.r.l. and commercially called Tromino® was used57,58,59. To ensure the repeatability of the measurements, some measurements were collected in all the campaigns, with different environmental conditions, and in more than one place over the same block to exclude the influence of the sensor location on the H/V results (see Supplementary Fig. 3). The instrument-soil coupling was ensured by the pin set supplied with the instrument. Each measure was acquired by orienting the sensor to the North and running for 20 min at a sampling frequency of 512 Hz and 256 Hz in the 2011–2012 and 2023 campaigns, respectively. The time length of 20 min was selected because this is a common practice in HVSR measures, e.g. for microzonation purposes (see e.g., the SESAME project protocol18,60), and if the eigenfrequencies are not considered in the interpretation of data acquired, one can wrongly interpret some H/V peaks. Acquired data were analysed by means of Geopsy software (www.geopsy.org, last accessed in May 2025) that implements the SESAME project guidelines18,60. To obtain the components’ spectra, and thus the H/V ratio, each trace was analysed to isolate the most stationary part of the signal. Then, data were filtered using the STA/LTA ratio anti-triggering on the raw signal, subdivided into non-overlapping windows of 20 s, and smoothed by a Konno-Ohmachi function61. Moreover, for each trace, the directivity and the particle motion analyses were also carried out. Finally, the polarisation analysis of each trace was carried out by means of the WAVEPOL tool26,27 which allowed for obtaining the ellipticity, the dip, and the strike graphs.

The numerical simulations have been performed with open-source software. Meshing has been performed using Gmsh52. CalculiX54 has been used to perform the modal analysis; PrePoMax62 has been used for the visualisation of the FEM results. The parameters used for these simulations are described earlier in the text (see Section ‘Vibration modal analysis of a single block constrained at the base’).

Data availability

Seismic noise data used in the text can be downloaded from https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17521125. These data cannot be used without citing the source.

Materials availability

Seismic noise data are available from the authors on reasonable request.

References

Clough, R. W. & Penzien, J. Dynamics of Structures 2nd edn (Computers and Structures, Berkeley, Calif., 2010).

Kramer, S. L. Geotechnical earthquake engineering. in Prentice-Hall International Series in Civil Engineering and Engineering Mechanics (Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 1996).

Spillmann, T. et al. Microseismic investigation of an unstable mountain slope in the Swiss Alps. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 112, 2006JB004723 (2007).

Xu, N. W. et al. The dynamic evaluation of rock slope stability considering the effects of microseismic damage. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 47, 621–642 (2014).

Xie, M., Liu, W., Du, Y., Li, Q. & Wang, H. The evaluation method of rock mass stability based on natural frequency. Adv. Civil Eng. 2021, 6652960 (2021).

Häusler, M., Michel, C., Burjánek, J. & Fäh, D. Fracture network imaging on rock slope instabilities using resonance mode analysis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 6497–6506 (2019).

Glueer, F., Häusler, M., Gischig, V. & Fäh, D. Coseismic stability assessment of a damaged underground ammunition storage chamber through ambient vibration recordings and numerical modelling. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 773155 (2021).

Bessette-Kirton, E. K. et al. Structural characterization of a toppling rock slab from array-based ambient vibration measurements and numerical modal analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 127, e2022JF006679 (2022).

Pistrol, J., Kopf, F., Adam, D. & Kummerer, C. Deep vibrocompaction at the natural frequency of the soil response. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 150, 04024076 (2024).

Chopra, A. K. Dynamics of Structures: Theory and Applications to Earthquake Engineering 5th edn (Pearson, Hoboken, NJ, 2017).

Nakamura, Y. A method for dynamic characteristics estimation of subsurface using microtremor on the ground surface. Railw. Tech. Res. Inst. Q. Rep. 30 (1989).

Sgattoni, G., Lattanzi, G. & Castellaro, S. An experimental approach to unravel 2D ground resonances: Application to an alluvial-sedimentary basin. Earth Planets Space 75, 74 (2023).

Frischknecht, C. Seismic soil effect in an embanked deep alpine valley: a numerical investigation of two-dimensional resonance. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 94, 171–186 (2004).

Roten, D., Fäh, D., Cornou, C. & Giardini, D. Two-dimensional resonances in Alpine valleys identified from ambient vibration wavefields. Geophys. J. Int. 165, 889–905 (2006).

Rial, J. A. Seismic wave resonances in 3-D sedimentary basins. Geophys. J. Int. 99, 81–90 (1989).

Sgattoni, G. & Castellaro, S. Detecting 1-D and 2-D ground resonances with a single-station approach. Geophys. J. Int. 223, 471–487 (2020).

Di Martino, A., Sgattoni, G., Purri, F. & Amorosi, A. Seismic amplification of Late Quaternary paleovalley systems: 2D seismic response analysis of the Pescara paleovalley (Central Italy). Eng. Geol. 341, 107697 (2024).

SESAME. Guidelines for the implementation of the H/V spectral ratio technique on ambient vibrations. Measurements, processing, and interpretation. in Sesame: Site Effects Assessment Using Ambient Excitations (ed Bard, P.-Y.) 1–62 (European Commission—Research General Directorate, 2004).

Molnar, S. et al. Application of microtremor horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratio (MHVSR) analysis for site characterization: state of the art. Surv. Geophys. 39, 613–631 (2018).

Molnar, S. et al. A review of the microtremor horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratio (MHVSR) method. J. Seismol. 26, 653–685 (2022).

Kleinbrod, U., Burjánek, J. & Fäh, D. Ambient vibration classification of unstable rock slopes: a systematic approach. Eng. Geol. 249, 198–217 (2019).

Got, J. L., Mourot, P. & Grangeon, J. Pre-failure behaviour of an unstable limestone cliff from displacement and seismic data. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 10, 819–829 (2010).

Galea, P., D’Amico, S. & Farrugia, D. Dynamic characteristics of an active coastal spreading area using ambient noise measurements—Anchor Bay, Malta. Geophys. J. Int. 199, 1166–1175 (2014).

Iannucci, R., Martino, S., Paciello, A., D’Amico, S. & Galea, P. Engineering geological zonation of a complex landslide system through seismic ambient noise measurements at the Selmun Promontory (Malta). Geophys. J. Int. 213, 1146–1161 (2018).

Iannucci, R., Martino, S., Paciello, A., D’Amico, S. & Galea, P. Investigation of cliff instability at Għajn Ħadid Tower (Selmun Promontory, Malta) by integrated passive seismic techniques. J. Seismol. 24, 897–916 (2020).

Burjánek, J., Gassner-Stamm, G., Poggi, V., Moore, J. R. & Fäh, D. Ambient vibration analysis of an unstable mountain slope. Geophys. J. Int. 180, 820–828 (2010).

Burjánek, J., Moore, J. R., Yugsi-Molina, F. X. & Fäh, D. Instrumental evidence of normal mode rock slope vibration. Geophys. J. Int. 188, 559–569 (2012).

Dowding, C. H., Kendorski, F. S. & Cummings, R. A. Response of rock pinnacles to blasting vibrations and airblasts. Environ. Eng. Geosci. xx, 271–281 (1983).

Moore, J. R., Geimer, P. R., Finnegan, R. & Michel, C. Dynamic analysis of a large freestanding rock tower (Castleton Tower, Utah). Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 109, 2125–2131 (2019).

Finzi, Y. et al. Stability analysis of fragile rock pillars and insights on fault activity in the Negev, Israel. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 125, e2019JB019269 (2020).

Finnegan, R. et al. Ambient vibration modal analysis of natural rock towers and fins. Seismol. Res. Lett. 93, 1777–1786 (2022).

Timoshenko, S. LXVI. On the correction for shear of the differential equation for transverse vibrations of prismatic bars. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 41, 744–746 (1921).

Wang, C., Reddy, J. & Lee, K. Shear Deformable Beams and Plates (Elsevier, 2000).

Rao, S. S. Vibration of Continuous Systems 1st edn (Wiley, 2006).

Jaroszewicz, J. & Lukaszewicz, K. Analysis of natural frequency of flexural vibrations of a single-span beam with the consideration of Timoshenko effect. Tech. Sci. 3, 215–232 (2018).

Burjánek, J., Edwards, B. & Fäh, D. Empirical evidence of local seismic effects at sites with pronounced topography: a systematic approach. Geophys. J. Int. 197, 608–619 (2014).

Panzera, F., D’Amico, S., Lotteri, A., Galea, P. & Lombardo, G. Seismic site response of unstable steep slope using noise measurements: the case study of Xemxija Bay area, Malta. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 12, 3421–3431 (2012).

Panzera, F. et al. Geophysical measurements for site response investigation: preliminary results on the Island of Malta. Boll. Geofis. Teor. Appl. 54, 111–128 (2013).

Vella, A., Galea, P. & D’Amico, S. Site frequency response characterisation of the Maltese Islands based on ambient noise H/V ratios. Eng. Geol. 163, 89–100 (2013).

Farrugia, D., Paolucci, E., D’Amico, S. & Galea, P. Inversion of surface wave data for subsurface shear wave velocity profiles characterized by a thick buried low-velocity layer. Geophys. J. Int. 206, 1221–1231 (2016).

Devoto, S., Macovaz, V., Mantovani, M., Soldati, M. & Furlani, S. Advantages of using UAV digital photogrammetry in the study of slow-moving coastal landslides. Remote Sens. 12, 3566 (2020).

Hungr, O., Leroueil, S. & Picarelli, L. The Varnes classification of landslide types, an update. Landslides 11, 167–194 (2014).

Carrea, D., Abellan, A., Derron, M.-H. & Jaboyedoff, M. Automatic rockfalls volume estimation based on terrestrial laser scanning data. in Engineering Geology for Society and Territory, Vol. 2: Landslide Processes (eds Lollino, G. et al.) 425–428 (Springer, 2015).

Amirahmadi, A., Pourhashemi, S., Karami, M. & Akbari, E. Modeling of landslide volume estimation. Open Geosci 8, 360–370 (2016).

Xu, C., Bian, C., Yu, T. & Qiu, C. Estimation of landslide volume by machine learning and remote sensing techniques in Himalayan regions. Landslides 1, 16 (2025).

Kim, B., Cai, M., Kaiser, P. & Yang, H. Estimation of block sizes for rock masses with non-persistent joints. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 40, 169–192 (2007).

Zhang, Z., Liu, B. & Liu, J. Investigation on the vibration characteristics of rock based on circular plate and cylinder models: dimension, geometric shape and boundary condition. J. Mech. 40, 239–250 (2024).

Farrugia, D., Galea, P., D’Amico, S. & Paolucci, E. Sensitivity of ground motion parameters to local shear-wave velocity models: The case of buried low-velocity layers. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 100, 196–205 (2017).

Pischiutta, M. et al. Results from shallow geophysical investigations in the northwestern sector of the island of Malta. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 98, 41–48 (2017).

Garcia-Suarez, J., González-Carbajal, J. & Asimaki, D. Analytical 1D transfer functions for layered soils. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 163, 107532 (2022).

Devoto, S. et al. Geomorphological map of the NW coast of the Island of Malta (Mediterranean Sea). J. Maps 8, 33–40 (2012).

Geuzaine, C. & Remacle, J.-F. Gmsh: A 3-D finite element mesh generator with built-in pre- and post-processing facilities. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 79, 1309–1331 (2009).

Mantovani, M. et al. A multidisciplinary approach for rock spreading and block sliding investigation in the north-western coast of Malta. Landslides 10, 611–622 (2013).

Dhondt, G. & Wittig, K. CalculiX. http://www.calculix.de/.

Mantovani, M. et al. Coupling long-term GNSS monitoring and numerical modelling of lateral spreading for hazard assessment purposes. Eng. Geol. 296, 106466 (2022).

Biolchi, S. et al. Geomorphological identification, classification and spatial distribution of coastal landforms of Malta (Mediterranean Sea). J. Maps 12, 87–99 (2016).

Pazzi, V. et al. H/V measurements as an effective tool for the reliable detection of landslide slip surfaces: case studies of Castagnola (La Spezia, Italy) and Roccalbegna (Grosseto, Italy). Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 98, 136–153 (2017).

Song, C. et al. Landslide geometry and activity in Villa de La Independencia (Bolivia) revealed by InSAR and seismic noise measurements. Landslides 18, 2721–2737 (2021).

Innocenti, A. et al. Geophysical surveys for geotechnical model reconstruction and slope stability modelling. Remote Sens. 15, 2159 (2023).

Dal Moro, G. & Panza, G. Multiple-peak HVSR curves: Management and statistical assessment. Eng. Geol. 297, 106500 (2022).

Konno, K. & Ohmachi, T. Ground-motion characteristics estimated from spectral ratio between horizontal and vertical components of microtremor. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 88, 228–241 (1998).

Borovinšek, M., Williams, J., Svilans, T. & Michalski, T. PrePoMax.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. Mauro Soldati (University of Modena e Reggio Emilia, Italy) for giving us the opportunity to start researching landslides in Malta and Darren Saliba (Il-Majjistral Natural Park, Malta) for the technical support during all the acquisition campaigns. We would also like to thank the associate editor, Alireza Bahadori, and the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments and suggestions. No specific funding has been provided.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: V.P. and E.F.; design of the work: V.P., E.F., and S.D.; acquisition: V.P., E.F., and S.D.; analysis: V.P., E.F., and S.F.F.; data interpretation: all authors; visualization: V.P., S.F.F., and S.D.; writing first draft: V.P., E.F., S.F.F., and S.D.; revision: all authors; funding: EF, S.D., and G.C.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pazzi, V., Fornasari, S.F., Devoto, S. et al. Fast estimation of landslide blocks’ volume from seismic noise measurements. Commun Earth Environ 6, 1031 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02999-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02999-3