Abstract

River deltas support human settlements, sustain ecosystems, and form hydrocarbon reservoirs in ancient sedimentary basins. Their morphologies are shaped by a complex interplay of environmental factors, posing challenges for predicting their evolution. Here we show that characteristics of delta shoreline and distributary channels are antagonistically influenced by rivers and waves. We analyzed morphologies of 1344 global deltas using a convolutional autoencoder, an unsupervised machine learning model, to encode their characteristics into 70-dimensional feature vectors serving as quantitative morphological metrics. The X-means clustering of these metrics revealed eight distinct delta morphotypes, adding a complementary perspective on their conventional classification schemes. We then performed multiple regression analyses to predict the relative sediment fluxes from rivers, tides, and waves from the morphological metrics. The results exhibited that shoreline protuberance and well-developed distributary channels are promoted by stronger fluvial influences and inhibited by stronger wave influences. In contrast, tidal influences were less clearly associated with these morphological features. This data-driven framework contributes to a better understanding of how specific delta morphologies respond to both natural variability and anthropogenic disturbances, offering additional avenues for sustainable management and future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

River deltas are essential environments for human habitation, hosting diverse ecosystems, and serving as hydrocarbon reservoirs1,2,3. The morphologies of deltas are influenced by various fluvial and coastal environmental factors, which control the sediment transport processes shaping the deltaic landforms4,5,6. Since recent global climate change and human land use have considerably affected the fluvial and coastal environment, it has become increasingly critical to predict the morphological changes of deltas in response to future environmental changes7,8,9.

The diversity of delta morphologies is primarily controlled by fluvial sediment input and sediment redistribution by tidal and wave processes. Galloway4 proposed the three fundamental end-member morphotypes depending on the relative dominance of these forcings: river-, tide-, and wave-dominated deltas. Fluvial-dominance develops channel distributions and enhances shoreline seaward protrusion10,11. Tide-dominated deltas are distinguished by well-developed mouth bars, wide river mouths, and upstream-to-downstream trends in channel depth and sinuosity12,13,14,15. Wave processes promote longshore sediment transport and the formation of shoreline-parallel beach ridges, which disrupt the development of mouth bars11,16,17. These delta morphologies are expected to reflect the relative influences of environmental factors. However, due to their morphological diversity and complexity, challenges remain in quantitatively evaluating morphologies and connecting them to environmental factors.

Previous studies have attempted to quantify the Galloway ternary diagram4 from both morphological and process-based perspectives. Various morphological metrics have been proposed to characterize delta morphology, often relying on fundamental length scales such as channel width, longitudinal length, and depth6,11,14,18. Other metrics have focused on analyzing channel distributary patterns or shoreline morphologies19,20,21,22. From a process-based perspective, global sediment flux datasets have been introduced as proxies for fluvial, tidal, and wave energy, providing the first-ever quantified Galloway diagram9. These sediment flux dataset have also been combined with morphological metrics to support quantitative predictions of future deltaic changes. For instance, previous studies21,23 have analyzed the correspondence between the sediment fluxes and morphological metrics such as shoreline geometry, number of channel mouths, channel widening or the presence of spits, contributing to future predictions of delta morphology.

However, existing morphological metrics are often limited to quantifying specific components of deltas. For instance, the morphologies of distributary channel patterns, barrier islands, and elongated sand bars—features that may be strongly influenced by environmental factors12,16,24—are not thoroughly evaluated21,22,23. A more comprehensive feature detection approach becomes especially valuable when the influence of environmental forcings on delta morphology is not well understood. Therefore, it is essential to develop a method capable of comprehensively quantifying delta morphologies, including features overlooked by conventional metrics, to better elucidate the relationships between environmental drivers and deltaic form.

Another limitation of previous studies including the Galloway diagram is that their morphological classification of deltas was restricted to predetermined morphotypes associated only with specific forcings that govern delta geomorphology. For instance, multiscale shoreline structures were systematically quantified, categorized deltas into process-informed morphotypes, and analyzed their relationship to relative sediment fluxes from rivers, tides, and waves22. However, their method does not assess the extent to which each of these forcings contributes to the formation of the morphotypes. By predefining morphotypes and assuming controlling factors beforehand, this approach inherently excludes the possibility of identifying morphotypes influenced by unrecognized factors, such as variations in grain size or sea-level fluctuations5,6,24,25.

This study proposes an innovative approach that integrates data-driven morphological characterization with machine learning techniques to address these limitations. We employed a neural network model to extract quantitative morphological metrics that capture diverse aspects of the delta form beyond those measurable using conventional methods. Using these metrics, an unsupervised clustering analysis was conducted to identify emergent delta morphotypes without predefining their number or associated controlling factors. This integrated approach enables a quantitative assessment of the extent to which each environmental forcing influences delta morphology, while also allowing the discovery of previously unrecognized morphotypes that could be shaped by factors such as grain size and sea-level changes. In addition, regression analyses were performed to predict relative sediment fluxes from fluvial, tidal, and wave processes based on the extracted metrics. Ultimately, our findings provide a predictive framework for anticipating deltaic responses to ongoing and future environmental changes, both natural and anthropogenic.

Results

Quantification of delta morphologies and cluster analysis

This study developed a convolutional autoencoder (CAE) model to compress the morphological features in delta images into 70-dimensional latent codes as morphological metrics (Fig. 1). Here, 1344 delta regions were sampled from a database based on satellite images20,26, producing a standardized dataset of delta morphology for the training dataset (see Methods for details). The CAE model was trained on the image dataset for 100 epochs (Supplementary Fig. 1). The decoder of the trained CAE model was able to reconstruct images consistent with the input delta images (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). The reproduced images restored the general geometries of the shoreline and major distributary channels, as well as shoreline barriers (the Apalachicola and Ebro deltas) and elongated mouth bars (the Fly delta).

The network architecture of the convolutional autoencoder (CAE) model was constructed to output images similar to the input images, which indicates that the model compressed the input image into a 70-dimensional latent code at the middle of the network. Examples of the original and predicted delta images are shown on the left and right sides of the CAE model, respectively. The darker color in the predicted images indicates a higher probability that the pixels are classified into land regions.

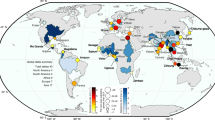

The X-means clustering method indicated that the delta morphologies were classified into eight morphotypes (Morphotypes 1–8) (Supplementary Table 1). The method was applied to the latent codes to quantitatively categorize the delta morphologies, and the optimal number of morphotypes for categorizing was determined based on the Bayesian Information Criterion. The average number of morphotypes across 50 trials of the same clustering was 7.86, with a standard deviation of 0.66. The t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) visualization27 indicated that each class occupied a different region in the morphological feature space (Fig. 2).

The deltas were primarily categorized based on shoreline and channel morphology. Morphotypes 1, 2, and 3 (Flat I–III) include the Eel, Tronto, and Senegal deltas, which are consistently characterized by flat shorelines and poorly developed distributary channels. Morphotype 1 (Flat I) deltas exhibit relatively well-developed (wider) channels. Morphotypes 2 (Flat II) and 3 (Flat III) are distinguished by subtle differences in shoreline concavity. Morphotypes 4 (Cuspate) and 5 (Arcuate) consist of deltas with cuspate and arcuate shoreline geometries, respectively. Morphotype 6 (Elongate) includes the Huanghe and Mississippi deltas, which are notable for their pronounced seaward shoreline protrusions. Morphotype 7 (Distributary) is defined by highly irregular shorelines resulting from extensively developed distributary channels, including the Flyand Mekong deltas. Morphotype 8 (Bayhead) is characterized by embayed shorelines or planforms laterally confined by surrounding landmasses, as seen in the Dnieper and Yenisei deltas.

Prediction of fluvial, tidal, and wave forcings

This study conducted regression analyses to quantify the influence of environmental factors on delta morphology. Because the preceding clustering analysis was based solely on morphological features, it remained unclear how delta morphologies are influenced by environmental forcings, such as fluvial, tidal, and wave processes. Therefore, as an independent analysis, three regression models were developed to predict the logit-transformed relative sediment fluxes of rivers (\({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{river}}}}}\)), tides (\({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{tide}}}}}\)), and waves (\({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{wave}}}}}\)) based on principal component (PC) scores derived from the latent codes (see Methods for details). These models were applied to 97 deltas out of 1344 global deltas.

The regression coefficients of the models indicated the morphological responses to the three environmental factors. In particular, delta geometries reflect wave and river processes. The R2 values of the regression models to predict \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{river}}}}}\) and \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{wave}}}}}\) were 0.377 and 0.426, respectively, which were larger than 0.203 for \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{tide}}}}}\) (Fig. 3 and Table 1).

The regression models were applied to 97 global deltas to predict (a), \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{river}}}}}\). (b), \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{tide}}}}}\). and (c), \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{wave}}}}}\), based on their morphological features. The deltas are colored by their morphotypes. The observed data are standardized. The solid blue lines indicate the 1:1 lines.

Based on the regression coefficient values, fluvial- and wave-induced sediment transport exhibited contrasting influences on delta morphology. The directions of maximum change in \(\hat{Q}{{{\rm{river}}}}\) and \(\hat{Q}{{{\rm{wave}}}}\) were visualized in the morphological feature space defined by the second and seventh principal component (PC2 and PC7) scores (Fig. 4a). The direction of maximum change in \(\hat{Q}{{{\rm{river}}}}\) was oriented toward the region characterized by lower PC2 and higher PC7 scores, where Morphotypes 5–8 are located. These morphotypes are distinguished by pronounced shoreline progradation and well-developed distributary channels (Morphotypes 5–7), in addition to embayed configuration (Morphotype 8). In contrast, the direction of maximum change in \(\hat{Q}{{{\rm{wave}}}}\) pointed toward the region with higher PC2 and lower PC7 scores, predominantly occupied by Morphotypes 1–4 (Flat and Cuspate).

a Delta morphological responses to changing \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{river}}}}}\) and \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{wave}}}}}\). The maximum change directions of \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{river}}}}}\) and \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{wave}}}}}\) are ploted on the morphological featurec space defined by PC2 and PC7. The regression cofficients of PC2 and PC7 are ( −0.44, 0.22) and (0.53, −0.21) for \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{river}}}}}\) and \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{wave}}}}}\), respectively (Supplementary Table 2). PC2 and PC7 exhibited the first and second lowest p-values for both regression models for \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{river}}}}}\) and \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{wave}}}}}\) (Supplementary Table 2). b Distributed delta morphotypes in a ternary diagram defined by \({\tilde{Q}}_{{{{\rm{river}}}}}\), \({\tilde{Q}}_{{{{\rm{tide}}}}}\), and \({\tilde{Q}}_{{{{\rm{wave}}}}}\). The deltas are colored by their morphotypes.

The deltas were also plotted in a ternary diagram defined by the relative sediment fluxes of rivers (\({\tilde{Q}}_{{{{\rm{river}}}}}\)), tides (\({\tilde{Q}}_{{{{\rm{tide}}}}}\)), and waves (\({\tilde{Q}}_{{{{\rm{wave}}}}}\)), (see Methods for details), comparing with the Galloway diagram4 quantified by Nienhuis et al.9. For fluvial and wave forcings, the diagram aligns with the regression results, as Morphotypes 5–8 and 1–4 are generally distributed in regions of higher \({\tilde{Q}}_{{{{\rm{river}}}}}\) and \({\tilde{Q}}_{{{{\rm{wave}}}}}\), respectively (Fig. 4b). The deltas distributed in the region with high \({\tilde{Q}}_{{{{\rm{tide}}}}}\) values had no clear trend with the morphotypes in this study (Fig. 4b).

Discussion

This study developed a method for quantifying delta morphology from image data using a CAE model. The proposed method overcomes the challenges associated with comprehensive feature detection of delta morphology. Previous studies have proposed various metrics to evaluate delta morphologies, but these metrics are often limited to specific delta components11,15,20,21,22. In contrast, the CAE model in this study comprehensively summarized the delta morphologies in the image data. The consistency between the input and output images from the trained CAE model implies that the model effectively captured the image features within the latent codes (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). This ability enabled the quantification of shoreline morphologies, channel developments, and deltaic components segregated from the mainland, such as shoreline barriers (the Apalachicola and Ebro deltas) and elongated mouth bars (the Fly delta) that are supposed to reflect the influences of rivers, tides, or waves12,16,28,29. Thus, latent codes can be considered appropriate descriptors of the diverse morphologies of deltas. Although the CAE model in this study considers only satellite imagery, its ability to identify features could be further improved by integrating additional datasets, such as topographic, bathymetric, and lithological information, which would enhance the detection of different landforms and anthropogenic structures.

The clustering analysis revealed that the global population of river deltas can be divided into eight distinct clusters, based purely on delta morphology. Here we provide the correspondence of the eight morphotypes and the process-based categorizetion in previous studies4,9,22. Morphotype 1–3 (Flat I–III) are categorized into wave-dominated deltas. Morphotype 6 (Elongate) is typical river-dominated form, while Morphotypes 4 and 5 (Cuspate and Arcuate) are often considered as transitional morphologies between river- and wave-dominated deltas. Morphotype 7 (Distributary) is classified into tide-dominated morphology. Morphotype 8 (Bayhead) is rather interpreted as an estuarine component30, although, due to their embayed geometries, Vulis et al.22 classified those deltas into tide-dominated deltas.

The identification of the eight morphotypes based on the Bayesian Information Criterion implies the possible existence of quasi-stable morphological states of deltas. In other words, delta morphologies were not distributed continuously but instead occupied densely concentrated regions within each cluster in the multidimensional morphometric space (Fig. 2). Previous studies have considered delta morphology a continuum between the three end-members. While this study does not refute the existence of three end-member concept, the clustering analysis indicated that the intermediate morphologies of global deltas exhibit a discrete set of morphological states. The morphotypes could be related to unique combinations of interacting boundary conditions and forcing parameters, as seen in the relationship between meandering and braided rivers31,32 or bedforms [e.g., see ref. 33]. The investigation of possible conditions leading to the emergence of each morphotype will be an important future research direction.

The regression analysis indicated notable links between processes and the delta geometries categorized into the eight morphotypes, facilitating the construction of predictive models for relative sediment fluxes from delta morphology. Based on the R2 values, the analysis suggested the best predictive ability of the relative sediment flux of waves (\({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{wave}}}}}\)) compared with those of rivers (\({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{river}}}}}\)) and tides (\({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{tide}}}}}\)) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2). The deltas in Morphotypes 1–4 (Flat I–III and Cuspate), which are characterized by flat or cuspate shoreline geometries and poorly-developed distributary channels, are associated with higher \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{wave}}}}}\) (Fig. 4). This trend aligns with the existing understanding that such characteristics reflect strong wave influences4,16,17,34.

On the other hand, the intense fluvial influence, indicated by higher river sediment flux values (\({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{river}}}}}\)), was estimated in Morphotypes 5–8 (Arcuate, Elongate, Distributary, and Bayhead) (Fig. 4). Previous studies have suggested that convex shorelines or well-developed distributary channels are characteristic of intense fluvial forcing4,10,11,35, which is consistent with the results. Also, the bayhead deltas are known to experience strong fluvial influence due to their landward position, limiting sediment redistribution by tides and waves30. In this study, despite of the morphological differences between bayhead deltas (Morphotype 8) and convex shoreline deltas (Morphotypes 5–7), the regression model successfully identified specific PC scores as the morphological metrics that correspond to higher \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{river}}}}}\) values (Table 1).

The regression analysis also revealed that the fluvial and wave influences act antagonistically. The maximum change directions orient oppositely between \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{river}}}}}\) and \({\hat{Q}}_{{{{\rm{wave}}}}}\) in the morphological feature space defined by PC2 and PC7 scores (Fig. 4a). The contrasting characteristics between Morphotypes 1–4 (Flat and Cuspate) and 5–8 (Arcuate, Elongate, Distributary, and Bayhead) represent the influences exerted by the wave and fluvial processes, respectively (Fig. 4). In general, fluvial processes promote progradation of deltas (i.e., constructive forcing), whereas marine processes (tides and waves) rework the sediment supplied from upsteram (i.e., destructive forcing)36. Specifically, it has been suggested that the dominance of fluvial processes promote shoreline protrusion and the development distributary channel networks, whereas wave process inhibits these morphological features11,17,35,37. This study quantified this antagonistic interactions between river and wave processes exerting a critical control on the overall delta configuration.

In contrast, the relationship between delta morphology and tidal influence was not well captured compared to those of rivers and waves. Morphotype 7 (Distributary), which are supposed to be typical tide-dominated deltas, do not fully align with higher relative sediment flux of tides (\({\tilde{Q}}_{{{{\rm{tide}}}}}\)) (Fig. 4b). This misalignment may occur because the deltas have not reach the equilibrium states under the present sediment flux conditions22. Also, it has been pointed out that the estimated sediment fluxes has uncertainty, which may be reflected in the misalignment with the observed delta morphologies22,23,38. Especially for tidal sediment flux, the prediction error may be accessed by improved numerical simulations with longer time scales and incorporating with field observations23. While Caldwell et al.37 indicated that the tidal effect is less pronounced than the wave effect in suppressing of shoreline protrusion and distributary channel development, tidal influence is nevertheless reflected in upstream to downstream trends of channel morphologies such as width, sinuosity, and depth15. Although the CAE model can analyze the shoreline geometries and development of distributary channels, it remains difficult for the model to capture the precise morphologies of distributary channels due to the resolution of images (Supplementary Fig. 3). Thus, the predictive ability of the regression model may also be improved by increasing the resolution of the delta image data or integrating the upstream channel morphologies into the analysis.

Still, this study highlights the necessity of incorporating additional controls to predict the delta’s response to future environmental changes instead of the conventional process-informed delta classification. While our analysis revealed that the relative sediment fluxes of rivers and waves partially represent the morphological variation of deltas, there is still dispersion in the trends (Figure 3 and Table 1). The dispersion in the regression analysis should have occurred because our analysis lacked other substantial processes, such as sea-level changes, grain sizes, and scales of depositional systems5,6,39. Our approach, which quantitatively captures the morphological diversity of deltas and links them to processes, will also contribute to detecting unexplored environmental factors and developing predictive morphodynamic models.

This study employs a data-driven framework to capture the intricate complexity of delta morphology and investigate its connections with fluvial, tidal, and wave influences. The proposed method allows for the identification of various morphotypes and their potential controlling factors, thereby offering an unconventional perspective on the examination of deltaic systems. Although further research is required to incorporate additional environmental variables, the findings presented provide a foundation for developing more comprehensive models of delta morphodynamics. This approach can enhance our understanding of how deltas evolve in response to both natural and anthropogenic changes and support future management and conservation efforts.

Methods

Development of delta morphological metrics

This study obtained 1344 delta images from a satellite-based database to generate a delta morphology dataset. Global Surface Water dataset26 was used in this process, which was derived from a water occurrence dataset representing the probability of water being present observed by satellites in 1984–2018 at each 30 m grid cell. The delta regions were sampled from the dataset with a square window ranging from approximately 4 km to 200 km in width, determined based on previously identified delta regions40. The sampling procedure was described by Vulis et al.22. The dataset was converted to binary images, where the values of 0 and 1 in each image correspond to land and water areas, respectively. In this conversion, the threshold was set to 50%, so that pixels with water probability smaller than this threshold were classified as land, and other pixels were classified as water. The images were then manually rotated to align the main channel directions and were resized to 224 × 224 pixels (Supplementary Fig. 2). R, Python 3.9, and Google Earth Engine were used in these procedures.

This study used a data-driven approach to quantify delta morphology. The convolutional autoencoder (CAE) model, which is an unsupervised machine learning method, can compress high-dimensional input data and is often designed for categorization tasks without the need for labeled input data41,42,43. Neural network models with convolutional layers are renowned for their robust capability in feature detection from image data and have been widely applied in image recognition44,45,46. In the CAE network, the features in the input data are reduced to their minimum dimension at the center of the network, which can be treated as a compressed representation of the input data41,42,43.

The CAE model was trained to compress delta morphologies into a feature vector with limited dimensions. The model architecture comprises 13 convolutional and two fully-connected (dense) layers with a symmetrical network comprising an encoder and decoder (Fig. 1). The encoder reduces the data size and compresses the features via convolution processing, whereas the decoder expands the data size and reproduces the image data. The CAE model was trained to minimize the difference between the input and output images. The categorical cross-entropy loss E was adopted as a loss function to train the CAE model, which takes the form:

where yi,c is an output of the CAE model, indicating a probability that the i-th pixel is classified into the c-th class. The parameter ti,c was set to 1 when the i-th pixel was classified into class c in the input image and 0 otherwise. As the CAE training progressed, the weight coefficients of the network were optimized to minimize the loss function value, i.e., to output similar image data from the decoder to that given to the encoder. The number of latent code dimensions was set to 70 according to the loss function values (Supplementary Fig. 4). The Adam method47 was adopted as the optimization algorithm in this study, consistent with its application in a previous study42. The learning rate was set to 0.00011 and optimized using the Bayesian optimization method with the Python library, Optuna48. Among the prepared delta images, 1075 images were randomly selected for the training dataset and 269 for the validation dataset. The CAE model used in this study was built and trained with reference to the network in Guo et al.42 using Python 3.9 with Tensorflow 2.8.249 and Keras 2.8.050.

The X-means clustering method was employed to categorize the delta morphologies. This unsupervised method automatically determines the optimal number of clusters based on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)51. Starting from a user-specified lower bound on cluster count (here set to two), X-means first applies standard k-means to partition the data and compute initial centroids. It then considers each cluster in turn for a potential binary split: for each candidate cluster, a local 2-means is performed, and the resulting two-cluster model is compared against the unsplit model using BIC. If the split yields a lower BIC-indicating that the increase in model complexity is justified by an improved fit-the cluster is permanently divided. This split-and-evaluate procedure iterates until no further BIC-improving splits are found, yielding both the final cluster count and assignment. The latent codes extracted from the CAE model were standardized to have zero mean and unit variance, and then used as input for clustering. The analysis was conducted using the Python library PyClustering52.

To visualize the clustering results, the t-SNE method was applied27. t-SNE is a nonlinear dimensionality reduction algorithm that first converts pairwise distances in the original high-dimensional space into joint probabilities-using a Gaussian kernel for the data points and a heavy-tailed Student’s t-distribution for the low-dimensional map-to capture local neighborhood affinities accurately. It then seeks an embedding that minimizes the Kullback-Leibler divergence between these two distributions, thereby preserving the local structure of the data while allowing moderate distortion of larger distances. In this study, t-SNE was applied to the standardized latent codes derived from the CAE model to project the clustering results into a two-dimensional space. We used scikit-learn’s t-SNE implementation53, setting the perplexity to 50 to balance focus between local and more global relationships, and employing an early-exaggeration factor of 12 for the first 250 iterations to improve cluster separation. The learning rate was left at its default value of 200, and the algorithm was run for 1000 iterations to ensure convergence of the embedding. These parameter choices produced a clear, interpretable layout in which points assigned to the same X-means cluster form compact islands, facilitating intuitive assessment of cluster cohesion and separation.

Multiple regression models for predicting delta morphological forcings

To uncover the relationships between delta morphology and environmental factors, this study proposed three multiple regression models to predict the relative sediment fluxes by fluvial, tidal, and wave forcings. The relative sediment fluxes \({\tilde{Q}}_{x}\) were defined as follows:

where Qriver, Qtide, and Qwave are the sediment fluxes of rivers, tides, and waves, respectively. The subscript x represents the river, tide, or wave. Qriver represents fluvial sediment supply, while Qtide and Qwave indicate sediment fluxes redistributed by tides and dispersed away from river mouths by waves, respectively. \({\tilde{Q}}_{x}\) ranges from 0 to 1, and is treated as the indicator of relative dominance of the three forcings, which can locate deltas in the ternary diagram (Fig. 4b). Then, the logit-transformation was applied to these parameters, which takes the form:

where \({\hat{Q}}_{x}\) denotes the logit-transformed relative sediment flux. \({\hat{Q}}_{x}\) ranges from − ∞ to ∞, which is appropriate for objective variables in the regression analysis. The Qx values were acquired for 97 of 1344 deltas sourced from previous studies9,21,22 (Supplementary Table 1). Before the regression analysis, applying the principal component analysis (PCA) to the latent codes, the morphological parameters were standardized and then summarized as PC scores (the PCA was performed for the latent codes derived from 1344 delta images). PC scores were selected as the candidates of the independent variables based on the cumulative explained variance over 80% (Supplementary Fig. 5). By examining all possible combinations of those PC scores, the regression models with the minimum Akaike Information Criterion scores were employed.

Data availability

The dataset of global delta morphology used in this study is publicly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17858928.

Code availability

The source code for the CAE model is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17858928.

References

Syvitski, J. P. & Saito, Y. Morphodynamics of deltas under the influence of humans. Glob. Planet. Change 57, 261–282 (2007).

Bhattacharya, J. P., Copeland, P., Lawton, T. F. & Holbrook, J. Estimation of source area, river paleo-discharge, paleoslope, and sediment budgets of linked deep-time depositional systems and implications for hydrocarbon potential. Earth-Sci. Rev. 153, 77–110 (2016).

Rovai, A. S. et al. Global controls on carbon storage in mangrove soils. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 534–538 (2018).

Galloway, W. E.Process framework for describing the morphologic and stratigraphic evolution of deltaic depositional systems, 87–98 (Houston Geological Society, 1975).

Porebski, S. J. & Steel, R. J. Deltas and sea-level change. J. Sediment. Res. 76, 390–403 (2006).

Caldwell, R. L. & Edmonds, D. A. The effects of sediment properties on deltaic processes and morphologies: A numerical modeling study. J. Geophys. Res.: Earth Surf. 119, 961–982 (2014).

Syvitski, J. P. et al. Sinking deltas due to human activities. Nat. Geosci. 2, 681–686 (2009).

Pelletier, J. D. et al. Forecasting the response of earth’s surface to future climatic and land use changes: A review of methods and research needs. Earth’s. Future 3, 220–251 (2015).

Nienhuis, J. H. et al. Global-scale human impact on delta morphology has led to net land area gain. Nature 577, 514–518 (2020).

Olariu, C. & Bhattacharya, J. P. Terminal distributary channels and delta front architecture of river-dominated delta systems. J. Sediment. Res. 76, 212–233 (2006).

Jerolmack, D. J. & Swenson, J. B. Scaling relationships and evolution of distributary networks on wave-influenced deltas. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L23402 (2007).

Dalrymple, R. W. & Choi, K. Morphologic and facies trends through the fluvial-marine transition in tide-dominated depositional systems: A schematic framework for environmental and sequence-stratigraphic interpretation. Earth-Sci. Rev. 81, 135–174 (2007).

Goodbred Jr, S. L. & Saito, Y.Tide-dominated deltas, 129–149 (Springer, 2012).

Nienhuis, J. H., Hoitink, A. & Törnqvist, T. E. Future change to tide-influenced deltas. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 3499–3507 (2018).

Gugliotta, M. & Saito, Y. Matching trends in channel width, sinuosity, and depth along the fluvial to marine transition zone of tide-dominated river deltas: the need for a revision of depositional and hydraulic models. Earth-Sci. Rev. 191, 93–113 (2019).

Anthony, E. J. Wave influence in the construction, shaping and destruction of river deltas: A review. Mar. Geol. 361, 53–78 (2015).

Nienhuis, J. H., Ashton, A. D. & Giosan, L. What makes a delta wave-dominated? Geology 43, 511–514 (2015).

Rossi, V. M. et al. Impact of tidal currents on delta-channel deepening, stratigraphic architecture, and sediment bypass beyond the shoreline. Geology 44, 927–930 (2016).

Shaw, J. B., Wolinsky, M. A., Paola, C. & Voller, V. R. An image-based method for shoreline mapping on complex coasts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L12405 (2008).

Edmonds, D. A., Paola, C., Hoyal, D. C. & Sheets, B. A. Quantitative metrics that describe river deltas and their channel networks. J. Geophys. Res.: Earth Surf. 116, F04022 (2011).

Broaddus, C. et al. First-order river delta morphology is explained by the sediment flux balance from rivers, waves, and tides. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100355 (2022).

Vulis, L. et al. River delta morphotypes emerge from multiscale characterization of shorelines. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL102684 (2023).

Paniagua-Arroyave, J. F. & Nienhuis, J. H. The quantified Galloway ternary diagram of delta morphology. J. Geophys. Res.: Earth Surf. 129, e2024JF007878 (2024).

Jerolmack, D. J. Conceptual framework for assessing the response of delta channel networks to Holocene sea level rise. Quat. Sci. Rev. 28, 1786–1800 (2009).

Orton, G. & Reading, H. Variability of deltaic processes in terms of sediment supply, with particular emphasis on grain size. Sedimentology 40, 475–512 (1993).

Pekel, J. F., Cottam, A., Gorelick, N. & Belward, A. S. High-resolution mapping of global surface water and its long-term changes. Nature 540, 418–422 (2016).

Van der Maaten, L. & Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-sne. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 9, 2579–2605 (2008).

Dan, S., Stive, M. J., Walstra, D.-J. R. & Panin, N. Wave climate, coastal sediment budget and shoreline changes for the Danube Delta. Mar. Geol. 262, 39–49 (2009).

Leuven, J., Kleinhans, M., Weisscher, S. & Van der Vegt, M. Tidal sand bar dimensions and shapes in estuaries. Earth-Sci. Rev. 161, 204–223 (2016).

Dalrymple, R. W., Zaitlin, B. A. & Boyd, R. Estuarine facies models; conceptual basis and stratigraphic implications. J. Sediment. Res. 62, 1130–1146 (1992).

Leopold, L. B. & Wolman, M. River channel patterns: Braided, meandering and straight. United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 282–B (1957).

Schumm, S. A. Patterns of alluvial rivers. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 13, 5–27 (1985).

Ohata, K., Naruse, H., Yokokawa, M. & Viparelli, E. New bedform phase diagrams and discriminant functions for formative conditions of bedforms in open-channel flows. J. Geophys. Res.: Earth Surf. 122, 2139–2158 (2017).

Bhattacharya, J. P. & Giosan, L. Wave-influenced deltas: Geomorphological implications for facies reconstruction. Sedimentology 50, 187–210 (2003).

Willis, B. J., Sun, T. & Ainsworth, R. B. Contrasting facies patterns between river-dominated and symmetrical wave-dominated delta deposits. J. Sediment. Res. 91, 262–295 (2021).

Fisher, W. L. Facies characterization of Gulf Coast Basin delta systems, with some Holocene analogues. Gulf Coast Assoc. Geol. Societies Trans. 19, 239–261 (1969).

Caldwell, R. L. et al. A global delta dataset and the environmental variables that predict delta formation on marine coastlines. Earth Surf. Dyn. 7, 773–787 (2019).

Zăinescu, F., Anthony, E., Vespremeanu-Stroe, A., Besset, M. & Tătui, F. Concerns about data linking delta land gain to human action. Nature 614, E20–E25 (2023).

Muto, T. et al. Planform evolution of deltas with graded alluvial topsets: Insights from three-dimensional tank experiments, geometric considerations and field applications. Sedimentology 63, 2158–2189 (2016).

Edmonds, D. A., Caldwell, R. L., Brondizio, E. S. & Siani, S. M. Coastal flooding will disproportionately impact people on river deltas. Nat. Commun. 11, 4741 (2020).

Chen, M., Shi, X., Zhang, Y., Wu, D. & Guizani, M. Deep feature learning for medical image analysis with convolutional autoencoder neural network. IEEE Trans. Big Data 7, 750–758 (2017).

Guo, X., Liu, X., Zhu, E. & Yin, J.Deep clustering with convolutional autoencoders, 373–382 (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

Li, F., Qiao, H. & Zhang, B. Discriminatively boosted image clustering with fully convolutional auto-encoders. Pattern Recognit. 83, 161–173 (2018).

LeCun, Y. et al. Backpropagation applied to handwritten zip code recognition. Neural Comput. 1, 541–551 (1989).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. (2014). arXiv.1409.1556.

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 60, 84–90 (2017).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv abs 1412.6980 (2014).

Akiba, T., Sano, S., Yanase, T., Ohta, T. & Koyama, M.Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework, 2623–2631 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2019).

Abadi, M. et al. Tensorflow: Large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous distributed systems. arXiv abs 1603.04467 (2016).

Chollet, F. et al. Keras (2015). https://keras.io.

Pelleg, D. et al. X-means: Extending k-means with efficient estimation of the number of clusters, Vol. 1, 727–734 (2000).

Novikov, A. PyClustering: Data mining library. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1230–1235 (2019).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Sediment Dynamics Research Consortium, sponsored by INPEX, JAPEX, and JOGMEC, and was also partially funded by an independent research grant provided by INPEX Corporation. We also extend our appreciation to the editors Dr. Olusegun Dada and Dr. Alireza Bahadori, as well as the two anonymous reviewers for their professional handling of the manuscript and constructive suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ryusei Sato conducted research design, data collection, model development, data analysis, and manuscript writing and revision; Hajime Naruse contributed to funding acquisition, research design, and manuscript revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

:Communications Earth and Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Olusegun Dada and Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sato, R., Naruse, H. Identifying controlling factors of delta morphology using a convolutional autoencoder. Commun Earth Environ 7, 121 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03144-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03144-w