Abstract

Background

This study explored the expected impact of two hypothetical HIV cure scenarios on quality of life, sexual satisfaction, and stigma among people with HIV and key populations (i.e., partners and communities of people with HIV and men who have sex with men without HIV) in the Netherlands.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among people with HIV and key populations from October 2021 until June 2022. We assessed quality of life, sexual satisfaction, and stigma using linear regression and mixed models to compare participants’ current situation with two hypothetical HIV cure scenarios: HIV post-intervention control, where HIV is suppressed without the need for ongoing antiretroviral treatment, but the viral reservoir is expected to persist, and HIV elimination, where HIV is completely removed from the body.

Results

Our findings show that people with HIV (n = 222) expect improved quality of life and sexual satisfaction, as well as reduced stigma, compared to their current situation following both post-intervention control and elimination. Key populations (n = 495) similarly expect improvements for both HIV cure scenarios, except no expected improvement was found for quality of life following post-intervention control. Participants aged 18 to 34 anticipate greater improvements from both cure scenarios than those over 34.

Conclusions

Both people with HIV and key populations without HIV expect an HIV cure to have a positive impact on quality of life, sexual satisfaction, and stigma. This impact is expected not only for HIV elimination but also for HIV post-intervention control, the development of which appears more feasible.

Plain Language Summary

Curing HIV might improve the quality of life, sexual satisfaction, and reduce stigma for people with HIV and their communities. An online survey was conducted among people with HIV and key populations in the Netherlands, comparing their current situation to two hypothetical HIV cure scenarios: one where HIV is controlled without treatment, and one where HIV is completely removed. Participants expected both scenarios to lead to better quality of life and sexual satisfaction, and less stigma. The results suggest that HIV cures could greatly benefit those with HIV, improving their lives even if the virus is only controlled and not completely eliminated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has transformed the outlook of HIV from a fatal to a manageable chronic disease1. Despite these advancements, HIV continues to significantly impact the quality of life (QoL), sexual satisfaction, and stigma experienced by people with HIV (PHIV) and key populations (e.g., partners of PHIV, communities of PHIV (such as friends and family), and those vulnerable to HIV in the Netherlands, mainly men who have sex with men (MSM))2. Part of this impact stems from the lifelong dependency on ART2,3, which has been reported to result in emotional and physical distress, potentially diminishing QoL2,3. In the Netherlands, both PHIV and key populations were reported to experience lower QoL compared to the general Dutch population4. Additionally, PHIV may endure ongoing burdens post-diagnosis, including HIV-related stigmatization, feelings of guilt, challenges related to disclosing their HIV status, and negative impacts on interpersonal relationships4. These burdens were found to persist over time2,5. Among key populations, there may still be substantial fear of HIV acquisition and experienced stigma related to sexual behavior despite U = U6. These negative experiences among PHIV and key populations underscore the urgent need for improved biomedical interventions for HIV, including the development of a cure2,7.

While a scalable HIV cure remains hypothetical, it may have the potential to improve experienced QoL and sexual satisfaction, and reduce stigma among both PHIV and key populations2,8,9. In line with the HIV cure target product profile, both PIC and HIV elimination may be considered curative interventions, each with distinct characteristics7,10. Previous research regarding an HIV cure primarily focused on the willingness of PHIV to participate in HIV cure trials11 or qualitatively explored the expected impact of HIV cure on the lives of PHIV and key populations2. Firstly, qualitative research indicated that only a cure that eliminates HIV from the body was deemed a true cure2,12,13,14. Indeed, qualitative research conducted in Australia reported that PIC was not considered a cure for HIV because it would not alleviate worry about transmission, concerns for friends and family, and stigma14. Secondly, it demonstrated that PHIV and key populations in the Netherlands perceived the ultimate impact of a cure for HIV to be the normalization of life2,14. Improvement was expected on three main themes: PHIV and key populations were hopeful that HIV cure would lead to improved QoL, would lead to sexual liberation and enhanced sexual satisfaction, and reduce HIV-related stigma2. Qualitative research from various contexts and geographical settings, including China, suggests that while an HIV cure may offer significant benefits, there may be some residual stigma in groups that have been historically stigmatized15,16. Thirdly, qualitative research illustrated that both PHIV and key populations were hopeful that a cure for HIV would lead to sex without fear of transmitting HIV and improve sexual satisfaction2. Fourthly, it also highlighted that PHIV hoped for a cure resulting in HIV elimination to put an end to HIV-related stigma2. Finally, prioritizing research to understand the potential impact of cure strategies for HIV, the partners of PHIV, communities, and those vulnerable to HIV in general, such as MSM, contributes to the implementation and dissemination of science and meaningful involvement of all those affected by HIV9,17,18,19,20.

While qualitative research suggested the potential positive impact of an HIV cure on three main themes, general QoL21, sexual satisfaction22, and stigma23, for PHIV and key populations, it remains unclear whether this expectation of a potential impact is widely supported among these populations. The potential impact of an HIV cure on these dimensions has not been explored quantitatively. Our study used a cross-sectional survey to quantify the expected influence of two different hypothetical HIV cure scenarios – HIV post-intervention control (PIC) and HIV elimination – on QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma among PHIV and key populations (i.e., partners and communities of PHIV and MSM without HIV) in the Netherlands.

Our research indicates that hypothetical HIV cure scenarios, including HIV elimination and HIV post-intervention control, are expected to positively influence quality of life, sexual satisfaction, and stigma among people with HIV and key populations in the Netherlands. While HIV elimination is seen as the most beneficial, HIV post-intervention control is also anticipated to improve sexual satisfaction and reduce stigma, albeit without enhancing quality of life for key populations.

Methods

This study involved a cross-sectional survey exploring the expected impact of two HIV cure scenarios on the QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma among PHIV and key populations vulnerable to HIV in the Netherlands. In our study, key populations were partners of PHIV, communities, and those vulnerable to HIV, such as men who have sex with men (MSM)24,25. Participants were eligible if they were Dutch or English-speaking, 18 years or older, living with HIV, or belonging to key populations, and if they provided informed consent.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht (UMCU): 20-546/C.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited between October 2021 and June 2022 from the Amsterdam Cohort Studies (ACS)26, the AGEhIV Cohort Study27, the infectious diseases outpatient clinic of the UMC Utrecht, the Dutch HIV Association28, Stichting ShivA29, Grindr30, and the Public Health Services of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Zuid-Limburg, Groningen, Utrecht, Gelderland-East, and Brabant-South East. Based on sample size calculations, we aimed to include between 700 and 1000 participants to conclude a mean difference of three points in QoL as assessed on the visual analog scale (VAS) of the EQ-5D (scores ranging from 0 to 100) before and after HIV cure (SD < 20, confidence level = 95%, power = 80%).

Questionnaire

Data were collected using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the UMC Utrecht and the ACS26. Tailoring was used to ensure participants were only shown questions relevant to them. All items were asked three times, unless otherwise stated, to assess a participant’s current QoL, sexual satisfaction, stigma, and demographic characteristics (section I), expected QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma after PIC (section II), and expected QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma after elimination (section III). Participants who completed only section I or the survey in an unrealistically short time (<5 min per section: PHIV n = 1; key populations n = 1) were excluded from the analyses.

A cure for HIV

Vignettes were used to present two hypothetical HIV cure scenarios: PIC and elimination. These vignettes were previously developed and tested for coherence and comprehensibility in a qualitative study involving 42 participants, which contains a complete description of the scenarios2. PIC entails the long-term suppression of HIV by the immune system without the necessity for ongoing HIV medication. However, in the event of PIC failure, HIV rebound may occur. HIV elimination refers to a scenario in which HIV, including its reservoir, is eliminated from the body. Following successful HIV removal, ongoing HIV medication is no longer required, but the possibility of reinfection remains. For each vignette, participants were asked about their QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma if the cure was available. Subsequently, participants were asked to express their preferences between PIC and elimination after the questionnaire (Q: You now read both descriptions of cure scenarios. Which treatment options would you prefer?).

Additionally, research indicates that a scenario such as PIC is more likely than complete HIV elimination7,8,10,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. This implies that PHIV and key populations will not have a choice between PIC or HIV elimination as a new treatment option. Thus, participants were not offered a choice or comparison between cure scenarios. To accommodate the current state-of-the-art research on HIV cure, no comparisons were made in our analyses in QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma between PIC and HIV elimination.

Participant characteristics

The following characteristics were included: gender (men, women, and non-binary), age (categorized into 18–34 years, 35–54 years, and ≥55 years), level of education (categorized into low–middle and high38), sexual orientation (LGBTQIA+ and heterosexual), relationship status (single and in a relationship), migration background (Dutch and non-Dutch), HIV status (PHIV and key populations without HIV), and, if applicable, time since HIV diagnosis (in years).

Changes in life after hypothetical HIV cure

Based on themes explored during thematic analyses of qualitative interviews, we included five questions to directly assess the expected change in life after a hypothetical HIV cure for internalized stigma, mental health, social activities, physical health, and overall QoL after PIC (section II) and elimination (section III)2. Life changes were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from much worse (1) to much better (5) (e.g., “How would your quality-of-life change?”). Response on each item was categorized into worse (scores 1-2), equal (score 3), or improved (scores 4-5).

QoL

QoL was defined in our work as the perception of a position in life regarding goals and expectations2. Participants were asked to rate their current QoL and QoL if the cure was available using the VAS of the EQ-5D21. The VAS measures general QoL ranging from the worst imaginable health (0) to the best imaginable health (100) the participant could imagine.

Sexual satisfaction

Sexual satisfaction was conceptualized through individual, interpersonal, and behavioral lenses, focusing respectively on personal satisfaction, partner interactions, and specific behaviors that contribute to satisfaction22,39. Sexual satisfaction was assessed using the short version of the New Scale of Sexual Satisfaction (N-SSSS)22 on a five-point Likert scale ranging from not at all satisfied (1) to extremely satisfied (5). The sum of the scores was computed for participants who had a sexual partner in the past six months (scores ranged from 12 to 60)22.

HIV-related stigma

HIV-related stigma, as perceived by people with HIV, encompasses negative attitudes, beliefs, and actions from others, as well as internalized feelings of shame and fear of disclosure. In this study, we focus on the public attitudes domain, which involves societal views and misconceptions about people living with HIV, significantly impacting their social interactions and quality of life23. To assess HIV-related stigma for the current situation (section I), we used the concerns with public attitudes towards the PHIV subscale of the short version of the Berger HIV Stigma Scale (HSS)23. Scores ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). The subscale was used in sections I, II, and III (scores ranged from 4 to 16).

Data analyses

QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma scales were transformed into Z-scores. Descriptive statistics were used to describe demographic characteristics, current QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma in our study population. Analyses were performed separately for PHIV and key populations. Missing values were not imputed. We examined whether gender, age, time since HIV diagnosis, relationship status, and migration background were associated with QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma using univariable linear regression analyses.

We used several methods to examine the expected impact of each cure scenario. First, we examined the percentage of participants who expected their QoL to improve, remain the same, or worsen after each cure scenario on the internalized stigma, mental health, social activities, physical health, and overall QoL items. Second, the expected change in QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma after PIC and elimination were examined separately for each outcome by comparing scores for the current situation and after each cure scenario using linear mixed models for both PHIV and key populations (i.e., twelve in total). In both groups, we examined whether expected changes were influenced by age (young vs. middle and young vs old), education, relationship status, migration background among PHIV, gender (men versus women), time since HIV diagnosis, and sexual orientation. Therefore, we added each characteristic and its interaction with the cure scenario in separate models (i.e., 78). Finally, we explored HIV cure preferences by examining percentages of participants who preferred PIC and elimination. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS, version 2940. No new code was developed for the analysis of this data.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 892 participants started the survey. Of these, 717 participants – including 222 PHIV and 495 participants from key populations – completed at least section I (i.e., current situation) and section II (PIC) of the questionnaire and were included in the analyses (Table 1). A total of 648 participants completed all three sections. Among PHIV, 91% identified as male, 60% were highly educated, and the mean time since HIV diagnosis was 13.6 years. Among participants from key populations, 97% identified as male, and 78% were highly educated.

Current QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma

Table 2 reports the associations between participant characteristics and current QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma. PHIV older than 55 years experienced higher QoL than PHIV between 18 and 34 years old. PHIV between 35 and 54 years old and older than 55 years experienced less stigma than PHIV aged 18–34 years. Among key populations, participants between 35 and 54 years old experienced higher QoL than key populations between 18 and 34 years. In addition, key populations between 35 and 54 years old and older than 55 years perceived less stigma towards PHIV than participants aged 18–34 years.

Expected change in life after hypothetical HIV cure: internalized stigma, mental health, social activities, physical health, and overall QoL

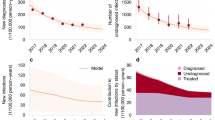

We measured whether PIC or elimination would worsen, not affect, or improve participants’ internalized stigma, mental health, social activities, physical health, and overall QoL using the expected change for QoL items (Fig. 1a–d). Across domains, improvements were expected by 52–70% of PHIV for both cure scenarios. For both cure scenarios, the most improvement was expected for the overall QoL (range 63–70% of PHIV), while the least improvement was expected for social activities (range 37–42% of PHIV). For key populations, improvements across domains were expected by 31–69% of participants. Across both cure scenarios, internalized stigma showed the highest expected improvement (61–69% of key populations), whereas physical health had the lowest anticipated improvement (31–36% of key populations).

X-axes represent percentages of participants who answered worse (black), same (light gray), or better (dark gray) for internalized stigma, mental health, social activities, physical health, and QoL after PIC or elimination. Panels a and b show the expected change among PHIV for PIC (n = 222) and elimination (n = 200). Panels c and d show the expected change among key populations for PIC (n = 495) and elimination (n = 443). PIC post-intervention control. QoL quality of life. Y-axes represent the following questions answered by participants: Internalized stigma: How would the degree to which you experience internalized stigma due to HIV change? Mental health: How would your mental health change? Social activities: How do you think that your social activities would change? Physical health: How would your general physical health change? QoL: How would your QoL change?

Expected change after cure: QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma scales

The expected changes in QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma between the current situation and after PIC and elimination are shown in z-scores in Fig. 2a–c. PHIV expected significantly improved QoL (PIC: 0.37, 95% CI: 0.27–0.47; elimination: 0.57, 95% CI: 0.46–0.68) and sexual satisfaction (PIC: 0.32, 95% CI: 0.22–0.42; elimination: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.40–0.68), and reduced stigma (PIC: −0.11, 95% CI: −0.20 to −0.02; elimination: −0.19, 95% CI: −0.30 to −0.08) after PIC and elimination compared to the current situation. Key populations also expected improvements for both HIV cure scenarios on sexual satisfaction (PIC: 0.34, 95% CI: 0.25 to 0.43; elimination: 0.46, 95% CI: 0.36–0.56) and stigma (PIC: −0.28, 95% CI: −0.36 to −0.20; elimination: −0.61, 95% CI: −0.69 to −0.53). For QoL, the expected improvement was found after elimination (0.17, 95% CI: 0.12–0.22) but not after PIC (0.02, 95% CI: −0.03 to 0.07) (Fig. 2d–f).

Y-axes represented the transformed Z scores of QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma scales. *All mean scores are transformed to Z scores to enable interpretation of expected change. Scores for current QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma differ slightly due to respondents who did not fully complete the survey (i.e., only completed sections I and II). Markers represent the regression coefficient from the mixed model analyses and represent mean differences in addition to group means. Gray circular markers represent PIC. Gray square markers indicate elimination. Panels a–c show the expected change among PHIV for PIC and elimination. Panels d–f show the expected change among key populations for PIC and elimination. Black error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Supplementary Information, Supplementary Figs. 1–12 and Supplementary Information, Supplementary Tables 1–12 provide the individual absolute scores transformed to Z scores to enable further interpretation and transparency of Fig. 2. QoL Quality of life, PIC post-intervention control, VAS visual analog scale, N-SSSS New Scale of Sexual Satisfaction, HSS Berger stigma subscale: concerns with public attitudes towards PHIV.

Role of participant characteristics on expected change after cure

We investigated the effect of participant characteristics on the expected change in QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma after PIC and elimination compared to the current situation in both groups. Five of the 78 linear mixed models demonstrated a significant effect of age (Supplementary Information, Supplementary Figs. 13–16, 21). For the other characteristics, few models showed a significant influence: one model showed an influence of gender, two models showed an effect of migration background, and one model showed an influence of relationship status on expected change (Supplementary Information, Supplementary figs. 17–21).

Models with an age effect showed that PHIV between 18 and 34 years expected more improvement in QoL and sexual satisfaction than PHIV aged 55 years and older after elimination. This group also expected a larger reduction in HIV-related stigma after both PIC and elimination (Supplementary Information, Supplementary Figs. 13–16). For QoL and stigma, current differences between young and older PHIV were expected to become smaller. For sexual satisfaction, the current difference between young and older PHIV was expected to become larger. Participants between 18 and 34 years from key populations expected a larger reduction in HIV-related stigma after elimination than older people, resulting in a smaller difference between age groups after cure (Supplementary Information, Supplementary Fig. 21).

Preference of PIC versus elimination

Finally, we assessed the preference of participants regarding PIC or elimination. Seventy-one percent of participants from PHIV and 88% of participants from key populations preferred elimination to PIC.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to quantitatively explore the expected impact of HIV cure scenarios on QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma, separately among PHIV and key populations. PHIV expected that both PIC and elimination would positively affect their QoL and sexual satisfaction and would also reduce stigma. Similarly, key populations expected a positive impact following both scenarios, except for no improvement in QoL following PIC. Additionally, the anticipated change in QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma resulting from an HIV cure varied by age. While a scalable HIV cure remains hypothetical8, we observed that participants generally expected an improvement in important domains following a hypothetical cure for HIV. This expected positive impact aligns with findings regarding HIV elimination from qualitative research conducted among both PHIV and key populations2,7,8,9,12,14,41,42,43,44. However, qualitative work from the Netherlands and Australia showed that PHIV and key populations did not consider PIC a cure for HIV as it would not alleviate burdens associated with HIV, such as fear of transmitting HIV and stigma2,14.

Additionally, current state-of-the-art research indicates that long-term ART-free control of the viral reservoir, akin to PIC, is more likely to become available than complete HIV elimination7,8,10,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Remarkably, our findings suggested a significant improvement not only for HIV elimination but also for the more achievable PIC curative strategy. In our PIC vignette, transfer of HIV was not possible, and monitoring after the cure was included. In the real world, the expected impact of an HIV cure may depend on the characteristics of the cure. Potential cure strategies for HIV that involve a risk of viral rebound and onward transmission7,45,46 may require increased vigilance for PHIV, their partners, and communities. This could also affect QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma7,45,46.

We detected several age-related effects in this study. Firstly, among both PHIV and key populations, we found that older participants reported currently experiencing less stigma and higher QoL compared to their younger counterparts. The positive current outlook on QoL and stigma among older participants may be attributed to their general optimism and hope regarding a potential cure for HIV in the future2,47. While optimism is a personality trait, it can also be cultivated over time47. Additionally, the accumulated experience of life with HIV over the years may contribute to the more positive outlook among older PHIV regarding their current experiences related to QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma48. Older PHIV and key populations in our study may have experienced the burden of HIV before ART, which includes fear of HIV acquisition or transmission, the necessity of extensive medication, and associated side effects. Comparing their situation with the past may have led to a more favorable perception of their present circumstances5,9,49.

Furthermore, older PHIV and key populations may be more accustomed to life with HIV compared to younger participants, who have not experienced the HIV epidemic of the 80 s and 90 s firsthand5,9,50. Secondly, among both PHIV and key populations, we identified several indications suggesting that participants between the ages of 18 and 34 expected greater improvements in QoL, sexual satisfaction, and more reduction in stigma following either PIC or HIV elimination compared to older participants. Smaller differences were ascertained in expected QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma between age groups after cure. These indications of greater expected improvement among participants aged 18–34 years may stem from an overestimation of the current influence of HIV on QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma. This hypothesis is supported by studies50,51,52,53,54,55,56 that have demonstrated an overestimation of the consequences of HIV on QoL and stigma, as well as the perceived severity of living with HIV compared to the actual experiences of PHIV.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is among the first to quantitatively assess the expected impact of two hypothetical HIV cure scenarios in both PHIV and key populations. However, our study has several limitations. Firstly, the findings should be interpreted within the context of a setting where biomedical interventions for HIV, such as ART and pre-exposure prophylaxis, are easily available and accessible. Further research is needed to investigate the expected impact of a cure for HIV across various geographical and cultural contexts. Secondly, certain subgroups, such as people with a migration background, women, and heterosexual PHIV, were underrepresented in our sample due to convenience sampling, limiting our ability to examine differences among these subgroups. To compare our sample of PHIV to PHIV in the Netherlands, we used the HIV Monitoring Report1,57. In terms of age and time since diagnoses, of the diagnosed PHIV in the Netherlands in 2021, 48% were aged between 35 and 54 years, and 40% were aged 55 years or older (based on HIV Monitoring Report data from 2021, unpublished). In our sample of 222 PHIV, 50% were aged between 35 and 54 years, and 36% were older than 55. Additionally, in 2021, 62% of those with HIV in care had HIV for more than ten years58. In our sample, 60% were diagnosed more than 10 years ago. These data suggest that our sample is comparable in age and time since diagnosis.

Based on the SHM report1, PHIV in the Netherlands, 10% had a migration background compared to the 14% in our sample. Compared to the 8% of women in our sample, it is estimated that 19% of all PHIV in the Netherlands are women, and 60% of all PHIV identify as MSM1,59. In addition, our sample is not representative of all key populations. The lack of representatives of our sample of PHIV and key populations may be due to convenience sampling, COVID-19, and challenges with stigma related to HIV among women54,60. Selection bias may have occurred, as an existing cohort in Amsterdam was used, which includes highly educated MSM who are used to fill in questionnaires. Compared to the total Dutch population, low-educated PHIV and key populations were underrepresented, and high-educated PHIV and key populations were overrepresented in the study sample61. Therefore, more research is needed to explore the impact of cure strategies for HIV further across populations.

Thirdly, our study may have attracted participants who are more hopeful about the prospects of a cure for HIV in the future, potentially biasing the expected positive changes reported. However, existing research suggests that individuals with chronic conditions often experience feelings of hopelessness, stress, fatigue, and despair62,63,64,65. For example, studies on diabetes patients have demonstrated critical rather than optimistic perceptions towards new interventions mentioned in the media66. In addition, convenience sampling might have led to a sample who experienced relatively little HIV-related stigma, better QoL, and sexual satisfaction compared to the general population. A cure for HIV may be more beneficial to persons who experience more stigma and poorer QoL. In that case, the expected improvements in our study may be an underrepresentation of the developments in a wider population.

Fourthly, in general, PHIV and key populations currently reported experiencing high scores on QoL and did not perceive high levels of public stigma (scores 7 out of 16). Qualitative research in other geographic settings mentioned an expected continued HIV-related stigma after HIV cure among stigmatized populations, exclusion by both family and society, workplace discrimination, feelings of inferiority, and psychological distress15,16,67. Contextual differences may influence the perceived impact observed in our study. We suggest exploring the impact of HIV cure, specifically on stigmatized populations, in other geographical settings and cultural contexts.

Lastly, due to numerous statistical tests, we focused on identifying the overall patterns observed for age rather than interpreting each significant finding. Therefore, caution is advised when interpreting differences in expected change concerning gender, migration background, and relationship status.

Conclusion

In conclusion, both PHIV and key populations generally expected a positive impact on QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma following either HIV PIC or elimination. Considering our current knowledge of HIV cure research, the development of an effective PIC scenario on a global scale appears much more feasible than achieving true elimination. Our data provide reassurance that people with and without HIV would nonetheless expect noteworthy benefits from PIC, including a reduction in experienced stigma. Nevertheless, we believe further research is needed to explore the perspective of partners of PHIV towards the impact of PIC on HIV transmission, prevention, protection, U = U, QoL, sexual satisfaction, and stigma.

Data availability

Only the authors have access to the raw data quoted in this study due to confidentiality. Any reasonable request for access to material relating to this study can be made directly to the corresponding author, who will decide on information sharing on a case-by-case basis.

References

van Sighem A. I. et al. HIV Monitoring Report 2022. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection in the Netherlands (Stichting HIV Monitoring, 2022).

Romijnders, K. et al. The perceived impact of an HIV cure by people living with HIV and key populations vulnerable to HIV in the Netherlands: A qualitative study. J. Virus Erad. 8, 100066 (2022).

de Los Rios, P. et al. Physical, Emotional, and Psychosocial Challenges Associated with Daily Dosing of HIV Medications and Their Impact on Indicators of Quality of Life: Findings from the Positive Perspectives Study. AIDS Behav. 25, 961–972 (2021).

Langebeek, N. et al. Impact of comorbidity and ageing on health-related quality of life in HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals. AIDS 31, 1471–1481 (2017).

van Bilsen, W. P. H., Zimmermann, H. M. L., Boyd, A., Davidovich, U. & Initiative, H. I. V. T. E. A. Burden of living with HIV among men who have sex with men: a mixed-methods study. Lancet HIV 7, e835–e843 (2020).

Koester, K. A. et al. “Losing the Phobia:” Understanding How HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Facilitates Bridging the Serodivide Among Men Who Have Sex With Men. Front. Public Health 6, 250 (2018).

Deeks, S. G. et al. Research priorities for an HIV cure: International AIDS Society Global Scientific Strategy 2021. Nat. Med. 27, 2085–2098 (2021).

Ndung’u, T., McCune, J. M. & Deeks, S. G. Why and where an HIV cure is needed and how it might be achieved. Nature 576, 397–405 (2019).

Romijnders, K. et al. The experienced positive and negative influence of HIV on quality of life of people with HIV and vulnerable to HIV in the Netherlands. Sci. Rep. 12, 21887 (2022).

Lewin, S. R. et al. Multi-stakeholder consensus on a target product profile for an HIV cure. Lancet HIV 8, e42–e50 (2021).

Dubé, K. et al. Willingness to participate and take risks in HIV cure research: survey results from 400 people living with HIV in the US. J. Virus Erad. 3, 40–50.e21 (2017).

Sylla, L. et al. If We Build It, Will They Come? Perceptions of HIV Cure-Related Research by People Living with HIV in Four U.S. Cities: A Qualitative Focus Group Study. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 34, 56–66 (2018).

Tucker, J. D., Volberding, P. A., Margolis, D. M., Rennie, S. & Barre-Sinoussi, F. Words matter: Discussing research towards an HIV cure in research and clinical contexts. J. Acquir Immune Defic. Syndr. 67, e110–e111 (2014).

Power, J. et al. The significance and expectations of HIV cure research among people living with HIV in Australia. PLoS One 15, e0229733 (2020).

Chu, C. E. et al. Exploring the social meaning of curing HIV: a qualitative study of people who inject drugs in Guangzhou, China. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 31, 78–84 (2015).

Wu, F. et al. Overcoming HIV Stigma? A Qualitative Analysis of HIV Cure Research and Stigma Among Men Who Have Sex with Men Living with HIV. Arch. Sex. Behav. 47, 2061–2069 (2018).

Power, J. et al. Perceptions of HIV cure research among people living with HIV in Australia. PLoS One 13, e0202647 (2018).

Dubé, K. et al. Re-examining the HIV ‘functional cure’ oxymoron: Time for precise terminology? J. Virus Erad. 6, 100017 (2020).

Noorman, M. A. J. et al. Engagement of HIV-negative MSM and partners of people with HIV in HIV cure (research): exploring the influence of perceived severity, susceptibility, benefits, and concerns. AIDS Care, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2024.2307381.

Marcos, T. A. et al. Beyond community engagement: perspectives on the meaningful involvement of people with HIV and affected communities (MIPA) in HIV cure research in The Netherlands. HIV Res. Clin. Pr. 25, 2335454 (2024).

EuroQol Research Foundation. EQ-5D-5L User Guide (EuroQol Research Foundation, 2019).

Brouillard, P., Štulhofer, A. & Buško, V. in Handbook of sexuality-related measures 496-499 (Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2019).

Berger, B. E., Ferrans, C. E. & Lashley, F. R. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs. Health 24, 518–529 (2001).

hiv-vereniging. Taalwijzer. 5 https://www.hivvereniging.nl/blog/belangenbehartiging/832-taalwijzer (2022).

UNAIDS. UNAIDS terminology guidelines (UNAIDS, 2024).

GGD Amsterdam. Amsterdam Cohort Studies (ACS), https://www.ggd.amsterdam.nl/beleid-onderzoek/projecten/amsterdamse-cohort/ (2021).

AGEhIV Cohort Study. AGEhIV Cohort Study, https://agehiv.nl/over-agehiv/ (2021).

hiv vereniging Nederland. hiv vereniging Nederland, https://www.hivvereniging.nl/ (2021).

ShivA. Spirituality, HIV, AIDS, https://shiva-positief.nl/ (2023).

Grindr LLC. Grindr: the world’s largest social networking app for gay, bi, trans, and queer people, https://www.grindr.com/ (2023).

Deeks, S. G. et al. International AIDS Society global scientific strategy: towards an HIV cure 2016. Nat. Med. 22, 839–850 (2016).

Dybul, M. et al. The case for an HIV cure and how to get there. Lancet HIV 8, e51–e58 (2021).

Grossman, C. I. et al. Towards Multidisciplinary HIV-Cure Research: Integrating Social Science with Biomedical Research. Trends Microbiol. 24, 5–11 (2016).

Henderson, G. E. et al. Ethics of treatment interruption trials in HIV cure research: addressing the conundrum of risk/benefit assessment. J. Med. Ethics 44, 270–276 (2018).

Phillips, A. N. et al. Identifying Key Drivers of the Impact of an HIV Cure Intervention in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Infect. Dis. 214, 73–79 (2016).

Lau, J. S. Y. et al. Time for revolution? Enhancing meaningful involvement of people living with HIV and affected communities in HIV cure-focused science. J. Virus Erad. 6, 100018 (2020).

Noorman, M. A. J. et al. The Importance of Social Engagement in the Development of an HIV Cure: A Systematic Review of Stakeholder Perspectives. AIDS Behav. 27, 3789–3812 (2023).

Centraal Bureau voor Statistiek (CBS). International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED), 39 (Centraal Bureau voor Statistiek (CBS), 2018).

Mark, K. P., Herbenick, D., Fortenberry, J. D., Sanders, S. & Reece, M. A Psychometric Comparison of Three Scales and a Single-Item Measure to Assess Sexual Satisfaction. J. Sex. Res. 51, 159–169 (2014).

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows v. 29.0 (IBM Corp, 2024).

Dubé, K. et al. “We Need to Deploy Them Very Thoughtfully and Carefully”: Perceptions of Analytical Treatment Interruptions in HIV Cure Research in the United States-A Qualitative Inquiry. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 34, 67–79 (2018).

Dubé, K. et al. ‘Well, It’s the Risk of the Unknown… Right?’: A Qualitative Study of Perceived Risks and Benefits of HIV Cure Research in the United States. PLoS One 12, e0170112 (2017).

Fridman, I. et al. “Cure” Versus “Clinical Remission”: The Impact of a Medication Description on the Willingness of People Living with HIV to Take a Medication. AIDS Behav. 24, 2054–2061 (2020).

Ma, Q. et al. ‘I can coexist with HIV’: a qualitative study of perceptions of HIV cure among people living with HIV in Guangzhou, China. J. Virus Erad. 2, 170–174 (2016).

Vansant, G., Bruggemans, A., Janssens, J. & Debyser, Z. Block-And-Lock Strategies to Cure HIV Infection. Viruses 12, 84 (2020).

Bailon, L., Mothe, B., Berman, L. & Brander, C. Correction to: Novel Approaches Towards a Functional Cure of HIV/AIDS. Drugs 80, 869 (2020).

Chopik, W. J., Kim, E. S., Schwaba, T., Kramer, M. D. & Smith, J. Changes in optimism and pessimism in response to life events: Evidence from three large panel studies. J. Res. Pers. 88, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2020.103985 (2020).

Lu, W.-Y. & Cui, M.-L. Research progress at hope level in patients with chronic non-malignant diseases. Chin. Nurs. Res. 3, 147–150 (2016).

Herron, L. M. et al. Enduring stigma and precarity: A review of qualitative research examining the experiences of women living with HIV in high income countries over two decades. Health Care Women Int. 43, 313–344 (2022).

Zimmermann, H. M. L. et al. The Burden of Living With HIV is Mostly Overestimated by HIV-Negative and Never-Tested Men Who Have Sex With Men. AIDS Behav. 25, 3804–3813 (2021).

Flint, A., Gunsche, M. & Burns, M. We Are Still Here: Living with HIV in the UK. Med Anthropol. 42, 35–47 (2023).

Namisi, C. P. et al. Stigma mastery in people living with HIV: gender similarities and theory. Z. Gesund. Wiss. 30, 2883–2897 (2022).

Sarma, P., Cassidy, R., Corlett, S. & Katusiime, B. Ageing with HIV: Medicine Optimisation Challenges and Support Needs for Older People Living with HIV: A Systematic Review. Drugs Aging 40, 179–240 (2023).

Stutterheim, S. E. et al. Trends in HIV Stigma Experienced by People Living with HIV in the Netherlands: A Comparison of Cross‐Sectional Surveys Over Time. AIDS Educ. Prev. 34, 33–52 (2022).

Vaughan, E., Power, M. & Sixsmith, J. Experiences of stigma in healthcare settings by people living with HIV in Ireland: a qualitative study. AIDS Care 32, 1162–1167 (2020).

Mahajan, A. P. et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS 22, S67–S79 (2008).

Sighem, A. I. et al. Monitoring Report 2019 (Stichting HIV Monitoring, 2019).

van Sighem A. I. et al. HIV Monitoring Report 2021. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection in the Netherlands, (Stichting HIV Monitoring, 2021).

Stichting HIV Monitoring. Jaarverslag 2023 (Stichting HIV Monitoring, 2024).

Stutterheim, S. E., Bos, A. E. & Schaalma, H. P. HIV-related stigma in the Netherlands (Aidsfonds, 2008).

Centraal Bureau voor Statistiek (CBS). Society: numbers of level of education, https://longreads.cbs.nl/trends18/maatschappij/cijfers/onderwijs/ (2018).

Coyle, L. A. & Atkinson, S. Imagined futures in living with multiple conditions: Positivity, relationality and hopelessness. Soc. Sci. Med. 198, 53–60 (2018).

Duggleby, W., Lee, H., Nekolaichuk, C. & Fitzpatrick-Lewis, D. Systematic review of factors associated with hope in family carers of persons living with chronic illness. J. Adv. Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14858 (2021).

Hirsch, J. K. & Sirois, F. M. Hope and fatigue in chronic illness: The role of perceived stress. J. Health Psychol. 21, 451–456 (2016).

Kylma, J., Vehvilainen-Julkunen, K. & Lahdevirta, J. Hope, despair and hopelessness in living with HIV/AIDS: a grounded theory study. J. Adv. Nurs. 33, 764–775 (2001).

Vehof, H., Heerdink, E. R., Sanders, J. & Das, E. They promised this ten years ago. Effects of diabetes news characteristics on patients’ perceptions and attitudes towards medical innovations and therapy adherence. PLoS One 16, e0255587 (2021).

Ncitakalo, N., Mabaso, M., Joska, J. & Simbayi, L. Factors associated with external HIV-related stigma and psychological distress among people living with HIV in South Africa. SSM Popul. Health 14, 100809 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the participants who are willing to share their experiences with us. In addition, we are thankful for their valuable contribution to our recruitment of all staff of the Amsterdam Cohort Studies, the AGEhIV Cohort Study, the infectious diseases outpatient clinic of the University Medical Center Utrecht, Bertus Tempert and Renee Finkelflügel from the Dutch HIV Association. We gratefully acknowledge Gail Henderson, Holly Peay, Stuart Rennie, and Fred Verdult for their involvement during the initial stages of this study. The authors thank Peter Zuithoff for his expert statistical consultations on linear mixed models. Finally, we thank our collaborators on the Aidsfonds project P-52901 (Daniela Bezemer, Godelieve de Bree, Janneke Heijne, Sebastiaan Verboeket, Udi Davidovich, Sigrid Vervoort, Berend van Welzen, and Ard van Sighem) for helpful discussions. The authors acknowledge funding of Aidsfonds Netherlands, grant number P-52901.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.A.G.J.R: Conceptualization; Data collection; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing. F.R.G.: Data collection; Data curation; Writing - review & editing. A.M.: Data collection; Writing–review & editing. M.L.V.: Resources; Writing–review & editing. M.D.: Resources; Writing–review & editing. P.R.: Investigation; Resources; Writing - review & editing. M.E.K.: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. P.N.: Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing - review & editing. M.S.v.d.L.: Methodology; Writing - review & editing. M.B.: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Formal analysis; Methodology; Supervision; Writing - review & editing. G.R.: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Supervision; Investigation; Project administration; Resources; Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare competing interests for: The institution of M. F. Schim van der Loeff received study funding from GSK; he served on advisory boards of GSK and Merck. P.R. has received grant support from Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, and Merck & Co. G.R. is an Editorial Board Member of Communications Medicine, but was not involved in the editorial review or peer review, nor the decision to publish this article. The other authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Bruno Spire and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Romijnders, K.A.G.J., Romero Gonzalez, F., Matser, A. et al. The expected impact of a cure for HIV among people with HIV and key populations. Commun Med 5, 152 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00853-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00853-3