Abstract

This Perspective explores equity and social justice perspectives on disability inclusion in Nigerian health care services. We note the physical, economic, and cultural barriers that limit persons with disabilities (PWDs) access. While national laws such as the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act (2018) and international guidelines such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD,2006) are available, access to health care among PWDs remains low in Nigeria. We contrast equity and equality in health care, advocating for policies favoring marginalized populations, and apply social justice theory to argue for equitable health care in Nigeria. We examine successful equity-based models of health care in other low- and middle-income countries and make recommendations, including stronger policy enforcement, disability-awareness training for health workers, and more community-based interventions. This Perspective stresses the need for more empirical research to guide policymaking and support disability-inclusive health care in Nigeria. Achieving a firmly inclusive healthcare system in Nigeria necessitates both structural change and interventions that promote social justice.

Similar content being viewed by others

The landscape of disability in Nigeria

Disability remains a public health and human rights issue across the globe, predominantly in low- and middle-income countries such as Nigeria, where structural healthcare access disparities disproportionately affect persons with disabilities (PWDs). According to the World Health Organization1, over 15% of the world’s population has some form of disability, while ~23 million Nigerians live with disabilities2. Despite international standards, such as the UNCRPD, and Nigeria’s enactment of the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act of 2018, various barriers persist in Nigeria’s healthcare system. The barriers include physical inaccessibility, attitudinal discrimination, financial constraints, and a lack of disability-trained healthcare workers3. Thus, PWDs in Nigeria have poorer health outcomes, lower service utilization rates, and higher exposure to preventable morbidity and mortality compared to their non-disabled counterparts.

To understand the challenges of incorporating disability into health, it is essential to envision equity and social justice as guiding principles. Healthcare equity is understood as the fair allocation of healthcare resources and services based on need and not privilege, so marginalized groups that include PWDs have access to adequate and appropriate care4. Healthcare social justice is more than equality, which entails structural change to eliminate systemic barriers and implement inclusive policy initiatives that empower vulnerable populations5. In Nigeria, these ideals are largely theoretical due to entrenched socio-economic inequalities, weak policy implementation, and widespread disability stigmatization6.

Disability inclusion in Nigeria’s health system is a public health imperative and moral responsibility. Disabling PWDs from access to mainstream healthcare services exacerbates health inequities and prevents Nigeria from reaching Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)7,8. Empirical data reinforce the need for disability-sensitive policy, community-based rehabilitation approaches, and accessible healthcare financing schemes to address gaps9. Besides, addressing these issues aligns with global disability-inclusive development approaches that reaffirm Nigeria’s international agreements and national health policies.

This Perspective critically analyses equity, social justice, and disability inclusion within Nigeria’s healthcare system and proposes that institutional reforms across policy implementation, health worker training, and infrastructural access need to be pursued to close the existing gaps in access to healthcare among persons with disabilities. Evidence-based review is utilized to underscore the structural and sociocultural drivers of exclusion and presents strategic routes toward a more inclusive and equitable health system in Nigeria.

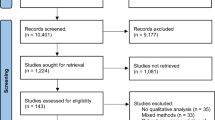

Evidence-based review methodology

We explored published literature, research, and information produced outside of traditional academic publishing and commercial channels on topics related to equity, social justice, and disability inclusion in Nigeria’s health system. Appropriate literature was identified through database searching using Google Scholar, Scopus, PubMed, and official institutional websites (e.g., WHO, UNCRPD, Nigerian Ministry of Health)10,11. Peer-reviewed journal articles, national policy documents, international guidelines on disability, and government and non-government implementation reports were included. We reviewed literature between 2006 and 2024, which coincided with some important milestones such as the adoption of the UNCRPD and the passing of Nigeria’s Disability Act12. The search was carried out in the PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases using keyword-focused queries such as “disability healthcare Nigeria,” “social justice,” “health equity,” and “inclusive health policy.” For learning across countries, we added case studies of the selected low- and middle-income countries of India, Rwanda, and South Africa based on their documented innovations in disability-inclusive health systems, relevance to Nigeria’s socio-economic context, and evidence of positive outcomes. These countries were selected purposively to allow for insightful policy comparisons and potential transferability.

In addition, we analysed legal documents, policy briefs, and disability rights mechanisms to explore the extent of their implementation in Nigeria. Analysis was concentrated on structural barriers, policy design, and social justice-informed interventions in health. A thematic approach guided our analysis13,14, utilizing social justice theory and the World Bank Disability Inclusion Framework to analyze the institutional, legal, and moral dimensions of healthcare inclusion. Synthesizing these results, we provide an integrated and evidence-based picture of the systemic barriers and transformative potential of equity-based healthcare reform for persons with disabilities in Nigeria.

Equity, social justice, and disability in healthcare

Achieving disability-inclusive health in Nigeria requires a nuanced understanding of equity, social justice, and their significance to health access. As global debates around health are increasingly centered on these principles, their implementation remains weak in the majority of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including Nigeria, where structural inequalities still prevail15. PWDs encounter unique barriers to obtaining healthcare in the form of physical inaccessibility, discrimination, unaffordability, and ineffective policy implementation. Thus, there is a need for evidence-based, specific interventions guided by equity and social justice principles. Without interventions, the disparities between disabled and non-disabled individuals will continue to expand, creating a cycle of exclusion and vulnerability.

The equity-equality divide is also a critical consideration in approaches to achieve inclusive healthcare for PWDs. While equality means the use of equal resources for everyone, equity recognizes that marginalized groups, such as PWDs, require different interventions to have equal health outcomes16. In Nigeria, health policies are more focused on achieving equal services for everyone rather than stopping the unequal disadvantage faced by PWDs, hence, systematic exclusion is perpetuated17. Equity-based approaches encourage resource allocation based on need, so there is not equal allocation, and individuals with disabilities are equipped with appropriate accommodations, including assistive technologies, disability-sensitive health financing, and trained personnel18. This is particularly crucial in sub-Saharan African countries such as Nigeria, where the majority of public health facilities do not possess basic accessibility amenities such as ramps, sign language interpreters, and disability-trained health workers19. For example, an audit of Abuja primary healthcare facilities by Nigeria Health Watch in 2021 revealed that just 6% of them were fully wheelchair accessible and that none of them had sign language interpreters or braille signage to cater to patients with communication or visual disabilities20,21. This level of infrastructural exclusion systematically denies PWDs access to equitable care. Furthermore, most Nigerian health professionals are poorly equipped in disability-inclusive care, consistent with findings from across many sub-Saharan African countries, where there is a consistent lack of training in disability-sensitive care among providers. This results in poor communication, exclusionary attitudes, and inadequate handling of high-risk health issues among PWDs16,22,23. Moreover, studies indicate that a lack of adequate infrastructure in healthcare, including inaccessible facilities and providers, prevents them from accessing much-needed healthcare24. This training deficit contributes directly to poor service experiences and reinforces discriminatory or paternalistic attitudes toward PWDs in clinical settings.

By failing to segment service delivery by need, the Nigerian healthcare system unintentionally reinforces structural barriers that prohibit PWDs from accessing healthcare fully. Therefore, embracing an equity-based health policy would mean placing investment in disability-friendly infrastructure first and increasing targeted social health protection systems to reduce financial burdens for PWDs. Notably, financial costs are still one of the major barriers to PWDs’ access to care in Nigeria. Even with the passage of the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) Act in 2022, the system remains heavily based on out-of-pocket (OOP) payments, totaling over 70% of total health expenditure in Nigeria25. To PWDs, whom we are aware are disproportionately unemployed or underemployed, this is a huge financial cost. Transportation costs also further exacerbate the problem, especially in the rural context, where facilities are distant and not disability friendly. In the absence of focused subsidies or disability-friendly insurance programs, such fiscal barriers will continue to contribute to poor health consequences in PWDs.

Social justice theories and health access

Social justice theories provide a moral framework for alleviating health disparities. Rawls’ theory of justice prioritizes the “difference principle,” advocating for redistributive policies that benefit the most disadvantaged groups, including PWDs26. In the Nigerian context, this demands legal and policy reforms that provide accessible health infrastructure and disability-inclusive service delivery. In the absence of such reforms, PWDs remain trapped in a cycle of exclusion, where their health needs are often secondary to broader national health agendas that overlook their specific difficulties. Sen’s capability approach also extends this line of argument one step further and demands the expansion of individual freedoms, particularly for disadvantaged groups27. Operationalizing Sen’s model of health implies that, beyond physical access, PWDs must also have the real ability to access services unencumbered by economic hardship, stigma, and discriminatory policies. This approach highlights the intersectionality of disability and social determinants of health, including education, employment, and social support, which all intersect to influence the ability of PWDs to demand and receive adequate healthcare28. A social justice approach, therefore, demands policies that, in addition to ensuring legal rights for PWDs, also address the socio-economic barriers to their living healthy lives. In Nigeria, where disability is still misconstrued and stigmatized, a holistic approach that combines legal enforcement, public sensitization, and health education is crucial to transforming public attitudes and shaping an inclusive healthcare environment.

The World Bank’s Disability Inclusion Framework29 provides a strategic guideline for integrating disability dimensions into health systems. It emphasizes three priorities: mainstreaming disability in health policies, strengthening inclusive service delivery, and facilitating participatory governance with PWDs. Nigeria’s implementation is, however, incomplete due to policy coordination deficits, underfunding, and weak monitoring mechanisms. Strengthening alignment with the World Bank’s model would necessitate capacity building for health workers, disability-inclusive health insurance policies, and legislative enforcement to check exclusionary tendencies within healthcare centers. This is particularly relevant given that the majority of Nigerian health workers have inadequate training in disability-sensitive healthcare, leading to subquality care experiences for PWDs30. Furthermore, the inclusion of disability-sensitive indicators in Nigeria’s national health surveys would provide the empirical data necessary for tracking progress and informing policy updates. Without data-driven decision-making, interventions are likely to be reactive rather than proactive and will fail to address the structural determinants of health inequities facing PWDs. In addition, the WHO model highlights the importance of cross-sectoral collaboration, not just with the health sector but also with education, transport, and social welfare, to create an integrated disability-inclusive environment.

Of interest, Nigeria ratified the UNCRPD in 2007 and enacted the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act in 201812, suggesting a formal commitment to the rights of people with disabilities. Gaps persist, nevertheless, in policy implementation, particularly in the physical accessibility of health facilities, healthcare worker training, and budgetary allocations toward disability-inclusive services31. While the UNCRPD coerces the progressive realization of PWDs’ rights to healthcare, Nigeria’s structural problems, from weak governance to socio-cultural stigmatization, consistently frustrate full compliance. For instance, while the law forbids discrimination against PWDs in the healthcare system, enforcement is weak, and violations are not reported due to fear of stigma or lack of legal literacy among PWDs. Mainstreaming disability inclusion within Nigeria’s broader UHC agenda would be a critical step in bridging these gaps. Additionally, leveraging international technical and financial support from the World Bank, WHO, and disability advocacy groups can support policy implementation and accountability. Another critical component is the involvement of PWDs in decision-making processes, as outlined in the UNCRPD principle of participatory governance. If PWDs are not engaged meaningfully in health policy development, there is a risk of well-intentioned but ineffective interventions that fail to address their lived experiences.

An equitable health system for people with disabilities in Nigeria must shift from equality-driven programming to policy driven by equity, social justice values, and international treaties15. Addressing the health inequities facing PWDs requires policy rollout, disability-inclusive service delivery, and governance arrangements that are participatory and incorporate the voices of people with disabilities. Placing Nigeria’s health system in the WHO Disability Inclusion Framework and implementing the UNCRPD in its entirety would be monumental strides toward achieving an equitable and socially just healthcare system.

Gaps still exist in disability-inclusive healthcare in Nigeria

Despite Nigeria’s policy declarations on disability inclusion, several barriers remain that hinder the capacity of PWDs to access equitable healthcare services. These barriers are multifaceted, encompassing physical infrastructure, communication, economic barriers, societal perceptions, and failures in implementing policy. These require a holistic, multi-sectoral response that converges with global best practices on disability-inclusive health care.

One of the most fundamental obstacles to PWDs’ access to healthcare in Nigeria is the physical inaccessibility of health facilities. Most hospitals and primary healthcare centers lack basic disability-friendly facilities, such as ramps, elevators, accessible toilets, and adjustable examination tables32. The absence of wheelchair-accessible paths and signposts in hospitals also contributes to the exclusion of individuals with mobility impairments. Studies have proven that PWDs tend to use wider healthcare service coverage when health facilities are accessible, leading to earlier diagnosis and better health outcomes16. Ambulation constraints, such as the lack of accessible public transport infrastructure, also hinder visits to health centers, particularly for rural dwellers. Universal design principles must be integrated into Nigeria’s healthcare infrastructure to improve accessibility to the system.

Amid growing attention on disability inclusion, healthcare access for PWDs in Nigeria remains acutely deficient. The 2022 WHO Global Report on Health Equity for Persons with Disabilities reports that PWDs in low-income nations such as Nigeria are twice as likely as those in other countries to report unmet healthcare needs, largely due to a combination of physical, financial, and attitudinal obstacles33. They are further disadvantaged by barriers to accessing skilled maternal health services, including inaccessible healthcare infrastructure, lack of knowledge about the needs of women with disabilities, mobility challenges, lack of disability-friendly transport, limited family and community support, and healthcare provider insensitivity34,35. For instance, in Nigeria, where a large proportion of maternal and child illnesses and deaths are recorded annually, women and girls with disability are described as the most vulnerable groups, especially in their limited access to health services, including maternal and child healthcare36.

Notably, although the health needs of people with disabilities are similar to others, they do require special services that are specific to their impairments, such as rehabilitation and health-related specialist care. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly exacerbated existing inequities in healthcare access for PWDs, revealing systemic gaps in emergency preparedness and continuity of care. Studies have shown that PWDs were more likely to experience care disruptions, loss of rehabilitative services, and reduced access to essential medications during lockdowns37,38. The challenge is compounded by the absence of consolidated data and limited empirical research focusing on the health and social care needs of people with disabilities in many developing regions39. Good quality healthcare has an anchor in effective communication, but PWDs, particularly those with hearing and visual disabilities, typically experience communication difficulties in Nigerian healthcare facilities. As hospitals do not have professionally trained sign language interpreters, patients with hearing disabilities have difficulty explaining their symptoms and receiving information on medical interventions16,32. Similarly, the nonavailability of health educational materials in audio or braille form precludes individuals who are visually impaired from gaining critical health information. Digital access remains underdeveloped, and few hospitals offer telemedicine services customized for PWD needs. The World Bank Disability Inclusion Framework40, emphasizes inclusive communication strategies, including training medical professionals in basic sign language, the provision of braille materials, and using digital technology to enhance the accessible dissemination of health information.

Financial availability is a main dissuader to access to healthcare for PWDs, as Nigeria’s healthcare system is very dependent on OOP expenditures41. The high cost of medical consultations, assistive equipment, rehabilitation services, and transportation disproportionately burdens PWDs, who are poor and mostly unemployed. Although the NHIA Act of 202242 aims to expand insurance coverage, PWD-targeted health benefits remain inadequately addressed. Without any specific subsidies or exceptions, the majority of PWDs remain unable to access the required healthcare services. Scaling up inclusive health financing arrangements, such as community-based health insurance programs tailored for PWDs, is crucial to bridge this economic gap43.

PWDs in Nigeria are typically discriminated against by healthcare providers, who themselves possess biases that reinforce ableist stereotypes32,41. Providers, in certain instances, perceive disabilities as “medical anomalies” rather than social conditions that require accommodation and, therefore, treat them paternalistically or dismissively. They outline verbal abuse, neglect, or denial of care in certain cases41. Beliefs on disability as a sign of either spiritual reasons or punishment also keep the majority of families away from formal medical intervention, with people and rather seeking help from faith healers instead. Disability sensitivity training for physicians and other workers, public education programs, and juridical measures for accountability for eliminating discrimination in clinics are required.

Though Nigeria signed the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities44, and enacted the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act (2018), the implementations were weak. Most health facilities lack clearly stated policies for the inclusion of people with disabilities, and funding for programs addressing disabilities is low. No effective accountability framework exists, so hospitals can continue as normal without accessible facilities or inclusive services. In addition, Nigeria’s national-level health policies are not disability-inclusive, making it difficult to track progress in disability-inclusive healthcare15,30. Enforcing mechanisms should be strengthened, more funds should be allocated, and disability-specialized data should be consolidated for use in national-level health planning for transformational change.

In addition to global instruments, including the UNCRPD, Nigeria subscribes to regional human rights under the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. The Protocol to the African Charter on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in Africa45, adopted in 2018, builds on the Charter’s equity and dignity provisions to mandate all states to ensure access to healthcare and social provisions for PWDs while adopting inclusive infrastructure and policies. Although the Protocol has not yet been ratified by Nigeria, it provides a firm benchmark for normative progress and regional best practices. Thus, rectification and implementation of the protocol would further align Nigeria with continental provisions of disability rights and provide further inclusive healthcare policies, practices, and legal reinforcements.

Furthermore, there are constitutional obligations under Nigerian Law towards PWDs beyond international commitments. Section 17(3)(d) of the Nigerian constitution mandates that the state direct its policy toward ensuring adequate medical provisions and facilities for all persons, a principle consistent with equity in health and healthcare46. Also, Section 42 ensures that individuals are protected from any form of discrimination, although disability is not explicitly listed, rights-based jurisprudence and legal interpretations extend these provisions to such marginalized groups as persons with disabilities. These constitutional provisions ensure stronger legal enforcement and alignment of the nation’s policies with the fundamental human rights principles enshrined in Nigeria’s law.

Advancing equity and social justice in disability-inclusive healthcare

Equity is central to making healthcare disability-inclusive so that PWDs get healthcare that addresses their individual needs and not a generalized one-size-fits-all model. In contrast to equality, which offers the same resources to everyone, equity acknowledges structural disadvantages and gives more importance to interventions that narrow down health disparities47. In Nigeria, where PWDs are disproportionately excluded from healthcare, equity-based policies are imperative to align national health systems with international disability rights norms and public health priorities.

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with disabilities44, universalizes access to healthcare as a human right, obliging signatory countries, including Nigeria, to discontinue discriminatory treatments and ensure disability-inclusive healthcare services. Article 25 of the UNCRPD commits PWDs to be provided with equal access to health care without discrimination, sexual and reproductive health care, preventive health care, and rehabilitation48.

The CPRD has provided a firm and authoritative interpretation of state obligations through its General Comments. Of strong relevance is General Comment No. 14 on Article 25 (2021), which clarifies that states must ensure ‘accessible, acceptable, and quality healthcare’ services for PWDs that are discrimination-free49. The comment insists on the obligation to remove all forms of barriers to healthcare, including but not limited to institutional, attitudinal, and legal barriers, and calls for the integration of reasonable accommodation and universal design models into healthcare systems. Hence, Nigeria as a party must align national legislation and policies within these expectations. However, Nigeria’s policies for health do not have categorical measures of enforcement, and as a result, PWDs continue to be locked out of essential services. Equity-based implementation of the UNCRPD in terms of legal accountability, strategic funding, and participatory health system planning needs to occur to break structural barriers.

Several LMICs have also been able to implement equity-focused healthcare programs that offer models for Nigeria. For instance, Rwanda’s Community-Based Health Insurance incorporates subsidized health coverage for PWDs, lowering economic barriers to accessing care50,51. The program has resulted in increased rates of utilization of health services among marginalized groups, proving the effectiveness of targeted health financing mechanisms. India’s Accessible Healthcare Initiative combines disability-inclusive primary healthcare centers with trained professionals and assistive technology. This approach has increased early intervention rates and reduced avoidable health complications among PWDs. Moreover, South Africa’s Disability Mainstreaming Policy requires all public hospitals to provide disability-sensitive healthcare training to healthcare professionals, resulting in improved health outcomes and patient satisfaction among PWDs52.

Deploying these models in Nigeria would mean scaling up disability-inclusive health insurance, adding disability-awareness training for providers, and scaling up community-based rehabilitation programs to reach underserved populations. UHC aims to provide healthcare access without financial hardship, but the majority of UHC policies overlook the special needs of PWDs. Equity-based models of UHC must have disability-specific benefits such as assistive devices, rehabilitation centers, and accessible transport to health facilities4,32. The Nigerian NHIA Act (2022) provides an opportunity to include disability-inclusive benefits, but current implementation lags in covering priority disability-related health services. Aligning UHC with an equity-oriented disability framework demands progressive policy change in the form of increasing insurance subsidies for PWDs, enhancing legal enforcement of disability rights, and requiring country-wide availability of disability-trained healthcare workers. Social justice in healthcare means abolishing structural boundaries confining quality access to healthcare for PWDs5. Equitable healthcare brings the interests of the marginalized in advance, i.e., providing equal treatment and provisions to the PWDs. This could be done in Nigeria by tightening policy implementation and developing capacity within the healthcare personnel, community programs, and intersectionality that brings forth the cumulatively augmented disadvantages in certain subgroups among PWDs. Most health facilities in Nigeria fail to meet accessibility requirements, and accountability structures are nonexistent15. Enhancing enforcement involves periodic compulsory audits of primary healthcare centers and hospitals, sanctions against non-compliant centers and incentives for disability-inclusive health services, and special funding allocation for disability-inclusive health programs in state and national budgets.

Healthcare professionals are likely to be ignorant of disability rights and inclusive care methods, leading to inadequate treatment and biased practices towards PWDs22,53. There is therefore a need to strengthen the training of healthcare providers on disability-inclusive delivery of healthcare services and to make this a requirement for all healthcare providers. Disseminating disability-sensitive training in medical and nursing schools can enhance providers’ ability to communicate effectively with PWDs, for example, by using sign language or assistive communication devices, providing respectful and dignified care, free of ableist prejudice, and adapting healthcare procedures and protocols to be disability-friendly. Community-based strategies are necessary in the provision of rural and disadvantaged groups of PWDs where healthcare is largely sub-standard.

Effective models will include building Disabled Persons Organizations (DPOs) that have a significant role to play in advocacy, health literacy, and service delivery54; their capacity will be built by funding, policy voice, and planning into healthcare so that the voices of PWDs guide service delivery. In Nigeria, Assistive Technologies and Telehealth Solutions offer limited access to affordable assistive devices (e.g., wheelchairs, hearing aids), severely curtailing the accessibility of healthcare to PWDs. An expansion of government and donor-sponsored programs of assistive technology delivery is necessary. Telehealth platforms, such as mobile health applications, can potentially bridge PWDs’ gaps in accessibility with mobility and communication requirements30,55.

While we focus on Nigeria, barriers to disability-inclusive healthcare, including lack of trained healthcare staff, underfunded policies, stigma (intrapersonal, societal, and provider-based), and infrastructural inaccessibility, remain common issues across low- and middle-income countries globally. The Nigerian experience demonstrates how implementation gaps are consequences of legislative progress (such as the Disability Act 2018) that lack strong enforcement mechanisms. This mirrors similar challenges experienced in countries such as Uganda and Kenya, where there is under-implementation of disability-inclusive policies despite their existence, owing to weak accountability structures and resource constraints56. However, Nigeria, over the years, has engaged with internationally recognized frameworks, including the World Bank Disability Inclusion model and the UNCRPD, showing how international pressure can catalyze national policy alignment. Thus, other LMICs can learn from Nigeria’s policy initiatives and advocacy by organizations such as DPOs with a strong emphasis on operationalization, emphasizing the need for financing, sustained political will, and grassroots inclusion, and not merely policy adoption.

Implementation and economic constraints

While we outline several policy solutions, their successful implementation is deeply constrained by resource limitations and structural inefficiencies in Nigeria’s health system. Health sector funding in Nigeria has consistently fallen below the 15% Abuja Declaration benchmark, hovering around 4–5% of national expenditure57,58. This chronic underfunding limits investments in infrastructure, disability-inclusive training, and assistive technology provision. Furthermore, the political economy of disability rights in Nigeria is marked by institutional fragmentation, weak inter-agency coordination, and low political salience of disability issues, particularly at the state level, where health service delivery is most concentrated. Corruption and lack of accountability also undermine budget implementation for disability programs. Effective reform thus requires not just policy design, but strong governance mechanisms, fiscal transparency, and political commitment to disability-inclusive development. Given the fiscal and structural constraints, phased intervention has to be implemented. Short-term measures such as mandatory disability-sensitivity training of health workers, the addition of simple ramps, and the appointment of disability-focal persons in primary health care centers are areas of top priority for Nigeria. The medium-term could focus on expanding the coverage of NHIA to include subsidies on assistive devices, increasing schemes of out-of-pocket (CBR), and collecting disaggregated data on disability. In the long term, reforms should entrench participatory budgeting of disability programs, adopt electronic telehealth platforms for remote access, and sign regional instruments like the African Disability Protocol to solidify rights-based implementation.

Conclusions

The healthcare system in Nigeria remains significantly inaccessible for individuals with disabilities (PWDs) due to structural, economic, social, and policy obstacles, and needs urgent reforms in favor of ensuring equitable and socially just access to healthcare. Strengthening the implementation of disability rights laws, such as the UNCRPD (2006) and Nigeria’s Disability Act (2018), through mandatory compliance audits and penalties for failure to comply is essential.

Notably, the CRPD Committee’s Concluding Observations to States59, raised concerns regarding the implementation of disability rights, especially in health and social care. The committee noted a lack of disability-disaggregated health data, poor implementation of the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act, marginalization of women and children with disabilities in healthcare delivery, and inadequate allocation of resources. These echo our discussion of gaps and reiterate the urgency to establish robust accountability, monitoring, and enforcement mechanisms. Incorporating these recommendations into Nigeria’s health and social policies could catalyze more equitable and inclusive service delivery in the country. Expansion of the health insurance benefit under the NHIA Act (2022) to include rehabilitation services, assistive devices, and disability-sensitive care will reduce financial barriers, and mandatory disability-awareness training for healthcare workers can eliminate discriminatory attitudes. Further investments from the government in assistive technology and telehealth solutions will also facilitate greater accessibility even in low-resourced areas, and involving DPOs in health policy decision-making will enable the mainstreaming of interventions with the experiences of PWDs. Moreover, additional empirical research is needed to provide nationally representative data on healthcare access disparities, investigate intersectional dimensions such as gender and socioeconomic status, and develop monitoring systems to evaluate the effectiveness of disability-inclusive policies. It is impossible to achieve UHC in Nigeria without bridging these gaps, and if not sustained, the country will not fulfill its commitments towards health equity and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 3).

References

World Health Organization. Disability. https://www.who.int/health-topics/disability (WHO, 2022).

National Bureau of Statistics. Reports|National Bureau of Statistics. https://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/elibrary/read/1181 (National Bureau of Statistics, 2020).

National Population Commission. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018—Final Report (National Population Commission, 2019).

Campinha-Bacote, J. Promoting health equity among marginalized and vulnerable populations. Nurs. Clin. North Am. 59, 109–120 (2024).

Hayvon, J. C. Action against inequalities: a synthesis of social justice & equity, diversity, inclusion frameworks. Int. J. Equity Health 23, 106 (2024).

Magidimisha-Chipungu, H. H. People Living with Disabilities in South African Cities: a Built Environment Perspective on Inclusion and Accessibility (Springer Nature, 2024).

The Lancet. Prioritising disability in universal health coverage. Lancet 394, 187 (2019).

The Federal Ministry of Information and National Orientation. SSAP Abba Isa Seeks Collaboration with UN Agencies to Accelerate Disability Inclusion in Nigeria - Federal Ministry of Information and National Orientation. https://fmino.gov.ng/ssap-abba-isa-seeks-collaboration-with-un-agencies-to-accelerate-disability-inclusion-in-nigeria/ (The Federal Ministry of Information and National Orientation, 2025).

Grills, N. & Varghese, J. Disability and community-based rehabilitation. in Setting up Community Health and Development Programmes in Low and Middle Income Settings (eds Lankester, T., Grills, N., Lankester, T. & Grills, N. J.) 0 (Oxford University Press, 2019).

Watson, M. How to undertake a literature search: a step-by-step guide. Br. J. Nurs. Mark Allen Publ. 29, 431–435 (2020).

Adams, J. et al. Searching and synthesising ‘grey literature’ and ‘grey information’ in public health: critical reflections on three case studies. Syst. Rev. 5, 164 (2016).

Yekeen, A. Six Key Things You Must Know About Disability Act, 2018 https://www.icirnigeria.org/six-key-things-you-must-know-about-disability-act-2018/ (2019).

Guest, G., Namey, E. & Chen, M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 15, e0232076 (2020).

Naeem, M., Ozuem, W., Howell, K. & Ranfagni, S. A Step-by-Step process of thematic analysis to develop a conceptual model in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 22, 16094069231205789 (2023).

Etieyibo, E. Rights of persons with disabilities in Nigeria. Afr. Focus 33, 439–459 (2020).

Gréaux, M. et al. Health equity for persons with disabilities: a global scoping review on barriers and interventions in healthcare services. Int. J. Equity Heal. 22, 236 (2023).

George, E. O. & Bartlett, R. L. Religion and the everyday citizenship of people with dementia in Nigeria: a qualitative study. Afr. J. Disabil. 13, 10 (2024).

WHO. Global report on health equity for persons with disabilities. Global report on health equity for persons with disabilities https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063600 (WHO, 2022).

The African Child Policy Forum. The African Report on Children with Disabilities: Promising starts and persisting challenges. Addis Ababa. https://africanchildforum.org/ (The African Child Policy Forum, 2014).

Nigeria Health Watch. Nigeria Health Watch Presents Findings from an Assessment of WASH Services in PHCs in FCT and Niger State. https://articles.nigeriahealthwatch.com/nigeria-health-watch-presents-findings-from-an-assessment-of-wash-services-in-phcs-in-fct-and-niger-state/ (Nigeria Health Watch, 2021).

Nigeria Health Watch. Primary Health Care in Nigeria: Progress, Challenges and Collaborating for Transformation - Nigeria Health Watch. https://articles.nigeriahealthwatch.com/primary-health-care-in-nigeria-progress-challenges-and-collaborating-for-transformation/ (Nigeria Health Watch, 2021).

Rotenberg, S. et al. Disability training for health workers: a global evidence synthesis. Disabil. Health J. 15, 101260 (2022).

Häfliger, C., Diviani, N. & Rubinelli, S. Communication inequalities and health disparities among vulnerable groups during the COVID-19 pandemic - a scoping review of qualitative and quantitative evidence. BMC Public Health 23, 428 (2023).

McClintock, H. F. et al. Health care access and quality for persons with disability: patient and provider recommendations. Disabil. Health J. 11, 382–389 (2018).

Hafez, R. Nigeria Health Financing System Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1596/30174 (World Bank, 2018).

RAWLS, J. A Theory of Justice. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvkjb25m (Harvard University Press, 1999).

Sen, A. The Idea of Justice1. J. Hum. Dev. 9, 331–342 (2008).

Frier, A., Barnett, F., Devine, S. & Barker, R. Understanding disability and the ‘social determinants of health’: how does disability affect peoples’ social determinants of health? Disabil. Rehabil. 40, 538–547 (2018).

Charlotte Vuyiswa, M.-N., Mari Helena, K., Janet Elaine, L., Anna Hill, M. & Trishna Rajyalaxmi, R. Disability inclusion and accountability framework. Wash. DC World Bank Group 1, 126977 (2022).

Nigeria Health Watch. Healthcare Services Should be Inclusive of Persons with Disabilities—Here is How https://articles.nigeriahealthwatch.com/healthcare-services-should-be-inclusive-of-persons-with-disabilities-here-is-how/ (2022).

Anietie, E. Nigeria Passes Disability Rights Law | Human Rights Watch. Nigeria Passes Disability Rights Law Offers Hope of Inclusion, Improved Access https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/01/25/nigeria-passes-disability-rights-law (2019).

World Bank. Social inclusion of persons with disabilities in Nigeria: Challenges and opportunities https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/nasikiliza/social-inclusion-persons-disabilities-nigeria-challenges-and-opportunities (2020).

WHO. Global Report on Health Equity for Persons with Disabilities. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063600 (WHO, 2022).

Ganle, J. K. et al. Challenges women with disability face in accessing and using maternal healthcare services in Ghana: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE 11, e0158361 (2016).

Ani, P. N., Eze, S. N. & Abugu, P. I. Socio-demographic factors and health status of adults with disability in Enugu Metropolis, Nigeria. Malawi Med. J. 33, 37–47 (2021).

Durojaiye, S. Women and girls with disabilities in Nigeria are the most vulnerable groups but the system doesn’t care. The ICIR- Latest News, Politics, Governance, Elections, Investigation, Factcheck, Covid-19. https://www.icirnigeria.org/women-and-girls-with-disabilities-in-nigeria-are-the-most-vulnerable-groups-but-the-system-doesnt-care/ (2020).

Goyal, D., Hunt, X., Kuper, H., Shakespeare, T. & Banks, L. M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with disabilities and implications for health services research. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 28, 77–79 (2023).

Cieza, A. et al. Disability and COVID-19: ensuring no one is left behind. Arch. Public Health Arch. Belg. Sante Publique 79, 148 (2021).

Magnusson, L., Kebbie, I. & Jerwanska, V. Access to health and rehabilitation services for persons with disabilities in Sierra Leone—focus group discussions with stakeholders. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22, 1003 (2022).

Rajyalaxmi, M.-N. et al. Disability Inclusion and Accountability Framework (English) https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/en/437451528442789278 (2022).

Adiela, O. N. P. Understanding disability and disability rights in Nigeria. Glob. J. Politics Law Res. https://eajournals.org/gjplr/vol11-issue-1-2023/understanding-disability-and-disability-rights-in-nigeria/ (2023).

Nigerian Health Insurance Authority. National Health Insurance Authority Act 2022 https://www.nhia.gov.ng/services-1/ (2022).

Aregbeshola, B. S. Out-of-pocket payments in Nigeria. Lancet 387, 2506 (2016).

United Nations Human Rights Office. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-persons-disabilities (OHCHR, 2006).

Juma, P. O. Ratification of the protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in Africa: An overview of the implications. Afr. Disabil. Rights Yearb. 12, (2024).

Federal Republic of Nigeria. Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999. https://nigeriareposit.nln.gov.ng/items/399df25a-52d0-4972-9365-c618cd3ddf5f/full (1999).

Lee, H., Kim, D., Lee, S. & Fawcett, J. The concepts of health inequality, disparities and equity in the era of population health. Appl. Nurs. Res. 56, 151367 (2020).

United Nations - DESA. Article 25 – Health | United Nations Enable. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/article-25-health.html (Department of Economic and Social Affairs Disability, United Nations, 2006).

General comment no. 14 (2000), The right to the highest attainable standard of health (article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights) (UN, 2000).

Chemouni, B. The political path to universal health coverage: power, ideas and community-based health insurance in Rwanda. World Dev 106, 87–98 (2018).

Kalk, A., Groos, N., Karasi, J.-C. & Girrbach, E. Health systems strengthening through insurance subsidies: the GFATM experience in Rwanda. Trop. Med. Int. Health 15, 94–97 (2010).

Sherry, K., Ned, L. & Engelbrecht, M. Disability inclusion and pandemic policymaking in South Africa: a framework analysis. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 26, 227–243 (2024).

Azizatunnisa, L., Rotenberg, S., Shakespeare, T., Singh, S. & Smythe, T. Health-worker education for disability inclusion in health. The Lancet 403, 11–13 (2024).

International Disability Alliance. Guide for Organizations of Persons with Disabilities: Driving Health Equity Through Inclusive Health System Strengthening. https://www.internationaldisabilityalliance.org/blog/guide-organizations-persons-disabilities-driving-health-equity-through-inclusive-health-system (International Disability Alliance, 2024).

Centre for Disability and Inclusion Africa. Nigeria and PWDs: any hope of bridging the digital divide? https://cdinclusionafrica.org/2023/08/14/nigeria-and-pwds-any-hope-of-bridging-the-digital-divide/ (Centre for Disability and Inclusion Africa, 2023).

Croese, S., Oloko, M., Simon, D. & Valencia, S. C. Bringing the Global to the Local: the challenges of multi-level governance for global policy implementation in Africa. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 13, 435–447 (2021).

Latifah, M. Pedro. Government budgetary allocations and the performance of the health sector in Nigeria. Dutse J. Econ. Dev. Stud. 8, 1–6 (2019).

World Bank Group. Current health expenditure (% of GDP)—Nigeria| Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS?locations=NG (2025).

United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-persons-disabilities (OHCHR, 2006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PCA conceptualized this piece and led the writing. PCA, MEA, and CKO worked on the development and flow of subtopics and guides. UFI, CKO, TA, SGA, MDU, OJO, and MN contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript critically for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Ebenezer Durojaye and Kara Ayers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Azubuike, P.C., Akinreni, T., Adai, S.G. et al. Equity and social justice perspectives on disability inclusion in healthcare services in Nigeria. Commun Med 5, 371 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01070-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01070-8