Abstract

Background

The Scaling Up Maternal Mental healthcare by Increasing access to Treatment (SUMMIT) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04153864) examined two solutions to improving access to psychotherapy for perinatal populations: telemedicine and task-sharing with non-specialist providers (individuals without prior specialized training or experience in delivering mental healthcare). The SUMMIT trial showed that telemedicine and non-specialist-delivered psychotherapy were non-inferior to treatment delivered in-person or by a specialist mental health provider. Our aim was to conduct an implementation assessment of task-sharing and telemedicine to inform best practices when providing access to psychotherapy treatment for perinatal patients in real world healthcare settings.

Methods

In this current study, we examined barriers and facilitators of task-sharing and telemedicine-delivered psychotherapy from a multistakeholder perspective (N = 105). We interviewed perinatal participants (n = 70) who received psychotherapy and specialist or non-specialist providers (n = 35) who delivered psychotherapy in the SUMMIT trial. We conducted an inductive thematic analysis.

Results

Our results show many facilitators of telemedicine across all stakeholder groups, including alleviating childcare needs through convenience, flexibly, and increased accessibility. Although perinatal participants and providers express that there are some benefits of in-person delivery (e.g., seeing physical cues and minimizing privacy concerns), we find that there are more barriers than facilitators of in-person psychotherapy. Regarding task-sharing, perinatal participants who received treatment from non-specialist and specialist providers report the same facilitators at similar rates, including capacity for active listening and empathy.

Conclusions

Our implementation assessment shows that telemedicine and task-sharing are acceptable, feasible, and patient-centred solutions to improve access to evidence-based psychotherapies across healthcare settings.

Plain language summary

The Scaling Up Maternal Mental healthcare by Increasing access to Ṯreatment (SUMMIT) trial tested two approaches to improve access to mental healthcare for pregnant or postpartum patients with depression or anxiety. This included (1) task-sharing with non-specialists (e.g., nurses and midwives) delivering a brief talk therapy via (2) telemedicine (online delivery). We interviewed 70 pregnant or postpartum participants and 35 providers from the study to understand the benefits and challenges of these approaches. Many people found telemedicine helpful in reducing common challenges, such as the need for childcare and travel. While some preferred in-person visits to pick up on body language, more challenges were reported with in-person care. Participants who received therapy from a non-specialist had similar positive experiences to those who received therapy from a specialist (e.g. a psychologist, psychiatrist or social worker). Overall, the study shows that non-specialist and telemedicine-delivered therapy are practical, patient-centred ways to improve mental healthcare during and after pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression and anxiety impact approximately 10–20% of perinatal (pregnant and up to one year postpartum) individuals in Canada and the United States1,2,3. Brief, evidence-based psychotherapies are among the most effective interventions in mental healthcare, but remain inaccessible for most. Access to psychotherapy is particularly relevant for perinatal populations because of the immediate and dual impact on patients and their children4. Untreated mental illnesses are a leading cause of pregnancy-related morbidity in the United States5 and elsewhere6. There are diverse barriers to accessing psychotherapy on individual and institutional levels, including arranging childcare and a lack of available mental health providers7.

Two possible solutions to address these barriers are telemedicine and task-sharing. Telemedicine refers to the use of virtual platforms, such as Zoom™, to deliver healthcare online. Telemedicine is a popular, acceptable, and patient-centred option among perinatal individuals8,9. Telemedicine reduces common barriers, such as time constraints and inconvenience associated with attending in-person appointments10,11. Task-sharing refers to training and leveraging non-specialist providers (NSPs) or individuals without a specialized degree or experience delivering psychotherapy to provide brief, structured psychotherapy treatments. Alleviating burdens on specialist providers (SPs)12,13,14 through task-sharing can increase access to mental healthcare15,16,17,18,19. Task sharing models via telemedicine have been shown to be feasible and acceptable among patients, including enhancing mental health support20,21. It is critical to examine barriers and facilitators to telemedicine and task-sharing to inform implementation and scale-up in real-world settings.

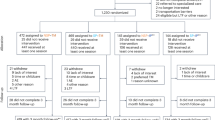

The Scaling Up Maternal Mental healthcare by Increasing access to Treatment (SUMMIT) trial was a pragmatic, multi-site, four-arm, randomised, non-inferiority clinical trial conducted across real-world healthcare systems in Canada and the United States17,18,19. In SUMMIT, perinatal participants with depressive and/or anxiety symptoms received a brief (6–8 session), manualised form of psychotherapy called Behavioural Activation (BA), which is currently open access22. The principle of BA is that simple actions can positively impact a person’s sense of connection to others and patients can learn skills in sessions to manage daily stressors and challenges, therefore reducing stress and increasing enrichment19,22,23. In SUMMIT, all perinatal participants (N = 1230) were offered the same BA treatment. Full descriptions of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, recruitment, provider supervision and training, the BA treatment, and other procedures in SUMMIT have been described elsewhere17,19,23,24. All perinatal participants were randomised to receive BA from either an NSP or SP and via telemedicine or in-person. In the SUMMIT trial, NSPs included nurses, midwives, and doulas and SPs included psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers. The primary results of the SUMMIT trial showed that telemedicine and NSP-delivered BA were non-inferior to BA treatment delivered in-person and by an SP19.

In this current study, we conducted an implementation assessment of relevant barriers and facilitators of task-sharing and telemedicine-delivered psychotherapy for perinatal populations. Qualitative methods identifying relevant barriers and facilitators are beneficial to assessing intervention processes and contextual factors25,26. Formative research using qualitative methods showed that task-sharing and telemedicine were feasible and acceptable by a range of stakeholders16,20,27,28; however, sample sizes were typically small or were not examined within real-world healthcare settings. Assessing facilitators and barriers can inform best practices when scaling-up access to psychotherapy treatment to meet the needs of perinatal patients in diverse healthcare environments29.

In this study, we conducted semi-structured interviews with a multi-stakeholder sample of perinatal participants from each treatment delivery arm and providers who participated in the SUMMIT trial. Specifically, this implementation assessment explores two questions: (1) What are the perceived facilitators and barriers of telemedicine compared to in-person delivered treatment from the perspectives of (a) perinatal participants who received the BA treatment, (b) NSPs and (c) SPs who delivered the BA treatment? and (2) What are the perceived facilitators and barriers reported by perinatal participants who received BA from an NSP relative to those who received BA from an SP?

Our study reveals that telemedicine facilitated access and mitigated common barriers that perinatal individuals and providers encounter when conducting in-person psychotherapy, including time constraints, transportation, and navigating childcare arrangements. Patients and providers alike emphasise that barriers to accessing in-person psychotherapy might be insurmountable for many perinatal individuals, given the diverse priorities of pregnancy and post-partum life. In addition, perinatal participants who received psychotherapy from an NSP endorsed the same facilitators -- and minimal barriers -- relative to those who received psychotherapy from an SP. Taken together, this study shows that telemedicine and task-sharing are feasible, desirable, and patient-centered approaches to improving access to psychotherapy for perinatal populations.

Methods

Setting

This qualitative implementation assessment was embedded in the SUMMIT trial (www.thesummittrial.com), which was conducted across real-world healthcare systems in Toronto, Ontario in Canada and Chapel Hill, North Carolina and Chicago, Illinois, in the United States17,19. The trial was registered on clinical trials.gov (NCT04153864). Ethical approvals were obtained from the following review boards: The Institutional Review Board of Clinical Trials Ontario Research Ethics Board [1895], UNC Biomedical Institutional Review Board [19–1786] and NorthShore University HealthSystem Institutional Review Board [EH18-129]. Trial details can be found in the study protocol17 and previously published manuscripts19,23,30.

Sample and procedures

Demographics and qualitative data came from a subset of perinatal participants who received treatment and providers (NSPs and SPs) who delivered treatment in the SUMMIT trial (described below).

Perinatal participants

Perinatal participants were recruited from the larger SUMMIT trial (N = 1230). The sample included adult perinatal individuals from each of the three hubs in Toronto, Chicago, and Chapel Hill who were either pregnant (up to 36 weeks) or 4–30 weeks postpartum and experiencing symptoms of depression and/or anxiety17,19,23. Exclusion criteria for perinatal participants in the larger SUMMIT trial have been described elsewhere17. Once enroled in the trial, perinatal participants were randomised to one of four study arms: (1) In-Person/SP; (2) In-Person/NSP; (3) Telemedicine/SP; or (4) Telemedicine/NSP17.

In SUMMIT, perinatal participants received a brief (6–8 session) BA treatment. BA is a manualised form of psychotherapy that emphasizes developing skills to problem-solve challenges and improve mood by incorporating meaningful and joyful activities into daily routines22. BA delivered by NSPs for the treatment of perinatal depression has previously been examined in clinical reviews18. The BA programme used in SUMMIT was adapted from the Healthy Activity Programme and the Alma Programme for perinatal depression and anxiety in real-world healthcare settings31,32. A full description of the BA treatment in SUMMIT has been described elsewhere23, and the SUMMIT Manual22 is an open-access document freely available (see www.thesummittrial.com). Perinatal participants randomised to the telemedicine arms received their sessions via a HIPPA/PHIPA-compliant version of WebExTM or ZoomTM.

For this implementation assessment, we recruited a purposive sample of SUMMIT perinatal participants who were treatment-completers (completed the full 6–8 sessions of BA) to ensure representation from SUMMIT’s four trial arms, with some arms having more or less representation in the dataset due to participant availability. To be eligible to participate in this qualitative study, perinatal participants consented to be contacted to participate in qualitative research upon enrolment in the SUMMIT trial and were contacted following treatment completion. An implementation assessment is a broad framework that evaluates the processes and practices of how an intervention is being delivered (in this case, psychotherapy delivered via telemedicine and task-sharing) rather than evaluating the outcomes of an intervention. To assess the implementation processes in the SUMMIT trial, we conducted qualitative interviews to identify relevant barriers and facilitators of psychotherapy treatment delivery across arms.

Treatment Providers

NSPs and SPs consisted of individuals who delivered the BA sessions in the SUMMIT trial. NSPs comprised individuals with previous work experience in the healthcare field but not mental healthcare, such as registered nurses and midwives. These individuals had no previous formal mental health expertise. SPs were psychotherapists, psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers with at least five years of experience in perinatal mental health. In SUMMIT, NSPs and SPs received a brief (3–4 day) training. NSPs participated in ongoing supervision sessions to deliver BA to perinatal participants in the trial19,30,33. To ensure patient safety, providers received training in safety protocols3,34 to assess, document, and respond to situations, including suicide risk, intimate partner violence, and child safety. To be eligible to participate in this current study, NSPs and SPs must have consented to participate in qualitative research and have been active providers in the trial at the time of qualitative data collection.

Data collection

Original, semi-structured interviews took place between November 2022 and December 2023. Alongside formative research23,35, we leveraged the inputs of our multi-stakeholder advisory group (e.g., people with lived experience, patient advocates, interdisciplinary clinicians and healthcare providers) to inform the interview guides used for this study. Perinatal and provider participants signed a digital consent form via REDCap™. All participants were invited to participate in this current study via email. Participants received study details, including their ability to withdraw from the study at any time, in (1) the recruitment email, (2) on the consent form, and (3) verbally before beginning the interview. Each interview lasted 40–60 minutes, and participants provided both written and verbal informed consent prior to participating.

In the interviews, we asked all participants - perinatal participants, NSPs and SPs - questions to explore their perspectives on receiving or delivering BA therapy either in-person or via telemedicine, based on their experience. We asked questions to examine what facilitated participants’ experience and what they liked about how they received/delivered the BA treatment. We then asked whether there were barriers participants encountered to receiving or delivering the treatment via telemedicine or in-person (see Supplementary Appendix A for interview guides). In addition, we asked perinatal participants for their perspectives about their respective provider. We aimed to examine differences or similarities in the experiences of our participants who received BA from an NSP compared to those who received BA from SP. Perinatal participants were asked to identify qualities that they liked about their providers and describe what, if anything, facilitated their BA sessions. Then, we asked participants what qualities they disliked and to describe what, if anything, was a barrier.

Data were collected from all three study sites until we reached saturation, though some arms ultimately had larger sample sizes due to participants’ availability. Nonetheless, we interviewed participants until we sufficiently captured the experiences across all four treatment arms. Self-reported demographic characteristics (age, race/ethnicity, marital status, and employment status) for perinatal participants were derived from demographic survey data collected upon participants’ enrolment in the trial. Three trained qualitative researchers conducted the interviews using a HIPPA/PHIPA-compliant version of Zoom™ and the interviews were recorded then transcribed. The qualitative researchers (NA, ZL, AC) involved in data collection and analysis had substantial experience engaging with perinatal patients and healthcare providers. All identified as white, cisgender women and acknowledged how their positionality can shape their perspectives in research. Prior to data analysis, they received training from a senior qualitative expert (doctorate level social scientist) with extensive experience working with diverse populations, who encouraged reflective practices and challenging biases.

Data analysis

Qualitative data were analysed using NVivo™ by three experienced qualitative researchers (NA, ZL, AC). We conducted an inductive thematic analysis36,37 in which we identified and analysed patterns that emerged directly from the data (rather than having predetermined themes) and synthesized those patterns into themes. We engaged in an iterative coding process to identify these patterns and themes across participants. A coding index was developed using the interview guide and allowed for emergent codes to be organized into themes. The most frequently endorsed facilitators and barriers reported by each participant group were then identified. Coding was done through a four-step process: an initial, line-by-line coding stage, which was conducted using the initial coding index, followed by two focused coding stages, in which the initial codes were sorted, synthesized, and integrated to reflect recurring themes and subthemes that arose and a final coding stage in which key themes were identified. Inter-rater reliability between the three qualitative coders was calculated using Cohen’s Kappa (κ) coefficient, demonstrating excellent agreement (κ = 0.91)35. In addition, similar to previous studies17,30, the frequency of facilitators and barriers for each of the emergent subthemes was calculated to determine the most salient themes endorsed by each participant group.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Sample characteristics

Our full sample (N = 105) includes perinatal participants (n = 70, see supplementary Table 1 for demographics) and providers (n = 35, see Table 1 for provider demographics). Providers were comprised of NSPs (n = 15) and SPs (n = 20).

Barriers and facilitators of Telemedicine compared to In-Person psychotherapy

Table 2 compares the most commonly reported facilitators and barriers of telemedicine relative to in-person delivered psychotherapy from the thematic analysis of qualitative interviews. Participants were asked open-ended questions about facilitators and barriers; hence, the themes discussed below were not mutually exclusive options.

In line with the wider SUMMIT trial, and because the COVID-19 pandemic temporarily limited in-person psychotherapy, our qualitative sample included more perinatal participants who received BA via telemedicine (n = 39 of 70, 55.7%) and somewhat fewer who received BA in-person (n = 31, of 70, 44.3%). All of our NSP (n = 15) and SP (n = 20) participants delivered BA via telemedicine, and a subset of those same NSPs (n = 13 of 15, 86.7%) and SPs (n = 15 of 20, 75.0%) also delivered BA in person. Themes expressed by participants were the same across groups, and all participant groups endorsed more facilitators than barriers to receiving/delivering BA via telemedicine. We also did not find differences in themes that emerged between US and Canadian participants. We outline our findings below.

Facilitators of telemedicine-delivered psychotherapy

Convenience, flexibility, and accessibility

The most endorsed facilitator across all stakeholders was that telemedicine-delivered psychotherapy is convenient, flexible, and accessible (Table 2). Telemedicine was consistently described, in general terms, as allowing perinatal participants and providers to easily attend sessions. For example, telemedicine-delivered psychotherapy was described as easily fitting into patients’ and providers’ everyday schedules and lives (e.g. patients could receive BA over their lunch break).

“The convenience factor is helpful for getting care. The virtual option is great for those who live further from the clinic. I like the flexibility of virtual.” (Perinatal_32_Telemedicine_Specialist)

“The convenience is [a facilitator]. You’re only dependent on yourself and the patient’s time and availability.” (Non-specialist_14)

Alleviating childcare needs

The second facilitator among all participant groups was that telemedicine minimised or eliminated the additional costs and stressors of finding childcare (Table 2).

“[Telemedicine] made childcare and everything easier…it’s much easier to ask others to cover for that one hour rather than ‘I need three hours [of childcare]’.” (Perinatal_06_Telemedicine_Specialist)

“A lot of [patients] have a spouse or a partner who works online, so while their partner is on lunch, [they can watch] the baby [while] they’re having their session. I think it’s easier to find childcare for an hour versus [the] commute plus the hour.” (Specialist_11)

Existing familiarity with online platforms

The third facilitator reported by all stakeholder groups was that participants’ familiarity with online platforms helped facilitate BA via telemedicine. This theme was most prevalent among perinatal participants (n = 16 of 39, 41.0%), with a smaller portion of NSPs (n = 2 of 15, 13.3%) and SPs (n = 5 of 20, 25.0%).

“[I use Zoom a lot] so it was pretty easy for me to do [BA] therapy online.” (Perinatal_60_Telemedicine_Non-specialist)

“I thought I wouldn’t be able to be authentic with the person on the other end, but you really can. There’s a very meaningful relationship that you could have over Zoom.” (Non-specialist_10)

Comfortable in own home

Last, across stakeholder groups, many expressed that receiving/delivering BA from home was a key facilitator of telemedicine. Perinatal participants described feeling safe and at ease and providers expressed that their patients seemed more comfortable and willing to share personal details when attending sessions within their own home (Table 2).

“I like being in the comfort of my own home.” (Perinatal_55_Telemedicine_Specialist)

“[Patients being] comfortable in their home helps them become comfortable… It helps them feel more natural especially because then they can breastfeed…and not be nervous about it.” (Specialist_08)

Barriers to telemedicine-delivered psychotherapy

There were three barriers to telemedicine-delivered treatment that were relevant to all participant groups. Notably, many perinatal participants (n = 11 of 39, 28.2%) and SPs (n = 9 of 20, 45.0%) explicitly stated that they experienced no challenges.

Technology issues

The most frequently endorsed barrier for all stakeholder groups was technology issues (see Table 2). This included internet connection issues and audio delays or video glitches while on Zoom™. Although technology issues were endorsed as a barrier, most participants clarified that technology issues were generally resolved quickly.

“Sometimes there would be technological issues that would make it harder to have a session on time… the audio would drop, and we would have to repeat ourselves, or the video would get choppy.” (Perinatal_33_Telemedicine_Non-specialist)

“Sometimes technical difficulties, like Wi-Fi issues, [were a challenge] but I’ve worked around it.” (Non-specialist_01)

Distractions and lack of privacy

Distractions and privacy issues were endorsed by all stakeholder groups as a barrier to telemedicine-delivered psychotherapy, though far fewer perinatal participants brought up this theme relative to providers (Table 2). Some participants stated that it could be challenging to focus due to potential distractions, such as incoming calls and messages, and a general lack of privacy in their home.

“It would have been a little bit easier if I could’ve been like: ‘Oh I have to go to therapy’ for me to get someone to [help]. I would go on my balcony to do my sessions and [my kids would] be knocking on the door.” (Perinatal_40_Telemedicine_Specialist)

Although not frequently discussed, some perinatal and provider participants voiced that some individuals might not be able to speak freely due to the presence of partners or family members:

“I’m really not convinced that one of the [participants] didn’t have [their] partner in the room off camera, monitoring and paying attention to what was being said. I had to negotiate carefully how I went through that with [them] because of danger concerns. I didn’t think I was really alone with this [participant], even though I’m asking [them] and I’m trying to go about it carefully.” (Specialist_16)

Bias towards in-person social connection

Most participants across groups felt they could engage with BA materials and develop a strong therapeutic connection via telemedicine. However, a small portion of perinatal participants (n = 7 of 39, 17.9%) and NSPs (n = 4 of 15, 26.7%) and a larger share of SPs (n = 9 of 20, 45.0%) had a bias or perception that in-person BA would be better than telemedicine, which was a barrier to their experience and engagement in sessions. As shown by the primary results of the SUMMIT trial, this preference did not prevent individuals from attending telemedicine sessions who, in fact, showed higher treatment completion rates than those randomized to in-person sessions19. Nonetheless, these participants who endorsed this theme perceived face-to-face encounters to be more natural and support the development of a “human connection”.

“I feel more connected when I’m face-to-face with somebody. For example, if I start crying, I’m sure [my SP] would have handed me a box of tissues but they can’t do that virtually.” (Perinatal_65_Telemedicine_Specialist)

“[I think there is] something nice about a human in-person connection that’s intangible that you don’t get with virtual.” (Specialist_05)

Facilitators of in-person-delivered psychotherapy

Physical cues assist rapport-building

All stakeholder groups who received or delivered BA in-person endorsed that in-person delivery facilitated social connection and rapport-building (Table 2). In particular, participants emphasized that face-to-face interactions and seeing non-verbal cues facilitated their treatment.

“There is a benefit to being in person, in terms of body language and developing the rapport with the person providing the care.” (Perinatal_27_In-person_Specialist)

“Reading body language, reading the nonverbal behaviour is more effective in-person, and I find myself more effective in-person… I am more distracted on the screen, and I know the patient sometimes is not as present as well.” (Specialist_07)

Preparing and leaving home as a form of activation

A facilitator endorsed only by perinatal participants (n = 10 of 31, 32.3%) and SPs (n = 7 of 15, 46.7%) was that attending BA sessions in-person can be a form of “behavioural activation.” In BA, participants incorporate meaningful activities to improve their mood. Attending BA sessions in person was a motivating factor for participants to leave their homes and engage in a positive activity for their well-being, which is a central principle of BA.

“It was time for me, I could just listen to music [in the car] or catch up on work calls, but regardless, it was ‘me time’ in the car that put me in a better frame of mind.” (Perinatal_21_In-person_Non-specialist)

“There’s something [about] getting out of their house [that] serves as behavioural activation in and of itself: ‘I’m going to get up, take care of my hygiene, put on clothes today.’ Often, family members are more willing to provide caregiving for infants when they have a physical appointment somewhere.” (Specialist_19)

Privacy and perception of confidentiality

Some in-person perinatal participants (n = 7 of 31, 22.6%) and NSPs (n = 4 of 13, 30.8%) endorsed that a facilitator of in-person BA was that a clinical office offered privacy and confidentiality. Interestingly, no SPs specifically endorsed this facilitator, although many addressed similar topics relating to privacy in other contexts, including endorsing lack of privacy as a barrier to delivering treatment via telemedicine.

“Definitely privacy, and, mentally for me, that it’s a safe space… it felt like I could be more candid. I’m not sitting here in my house with my family running around, feeling like I need to hold back.” (Perinatal_52_In-person_Non-specialist)

“There’s a greater sense of privacy [for both the participant and the provider] and sense of engagement… for some people, in-person is the only option because it’s a private safe place for them.” (Non-specialist_15)

Barriers to in-person-delivered psychotherapy

Arranging childcare

Arranging childcare was the most frequently endorsed barrier to attending in-person sessions among perinatal participants and SPs, and a small portion NSPs (Table 2). In direct contrast to the facilitator “alleviating childcare needs” reported by participants who received or delivered BA via telemedicine, attending treatment in-person required participants to arrange childcare for the length of the appointment and the associated travel time. For perinatal individuals who needed to bring their child with them to in-person sessions, having to feed or change their babies was described as distracting and more difficult to manage.

“Although it was made clear that I could bring the baby, it was a huge challenge to bring the baby anywhere.” (Perinatal_49_In-person_Specialist)

“If they’re postpartum, [they might have to] take their child… Your postpartum mom is so busy and so overwhelmed and doing so much in her day that adding in another layer is going to be prohibitive.” (Specialist_07)

Arranging travel

A commonly endorsed barrier across all stakeholder groups was the commute required to attend in-person sessions (see Table 2). Participants highlighted that arranging travel exacerbated stressors, time commitments, and costs.

“I was leaving an hour and a half [early] to get there most days so, that added extra time to the day.” (Perinatal_22_In-person_Non-specialist)

“I get anxious if I drive downtown, so I take [public transit]. That takes me roughly an hour and a half to get there, and an hour and a half to get back. That’s three hours of my day, and I have another job.” (Non-specialist_01)

Scheduling & cancellations

Although only endorsed by one perinatal participant, most NSPs and SPs expressed that they found “scheduling and cancellations” to be a barrier to in-person sessions (Table 2). This theme consolidates the feedback from providers who felt that the frequency of participants arriving late or cancelled sessions at the last minute was higher with in-person sessions, which resulted in frustration and shortened or more rushed sessions, as providers had to stick to their scheduled times for other patients and commitments.

“When people come in person, they’re more likely to be late, or they tend to miss sessions…so it’s actually much easier to deliver it virtually.” (Specialist_07)

Risk of illness

The last barrier to in-person sessions endorsed by all stakeholders was the risk of getting sick. NSPs (n = 6 of 13, 46.2%) and SPs (n = 7 of 15, 46.7%) reported this concern more frequently compared to perinatal participants (n = 5 of 31, 16.1%). The current study took place between November 2022 and December 2023, when COVID-19 became a less salient concern among participants who expressed being equally as concerned with exposure to other common sicknesses, such as cold and flu. Attending BA in-person in a hospital or doctor’s office brought up concerns of health risks to our perinatal and provider participants, and their families.

“[The risk of getting sick is] more stressful… because you’re dealing with babies. I’m sure it will be different in a few years, but it’s hard not to feel like: ‘I should just stay home,’ especially when RSV and COVID [are common].” (Perinatal_01_In-person_Specialist)

“As a provider, one of the bigger challenges was COVID. Both my own comfort level and resuming in-person care at the time, based on my own personal preferences and needs and my family’s needs and concerns with [exposure to illness and the risk of getting sick].” (Specialist_14)

Barriers and facilitators of psychotherapy delivered from an NSP relative to an SP

Table 3 summarizes the most commonly endorsed facilitators and barriers to task-sharing from the perspectives of perinatal participants (n = 70) who received BA and from an NSP (n = 29) or an SP (n = 41). Both groups reported the same themes at equitable rates. They reported far fewer barriers than facilitators, regardless of whether they received BA from an NSP or an SP.

Facilitators of NSP relative to SP-delivered psychotherapy

Capacity for empathy & validating feelings

Perinatal participants expressed that their provider’s ability to be “empathetic and validating” facilitated treatment delivery (Table 3). Perinatal participants reported this facilitator at equitable rates regardless of whether they received treatment from an NSP or an SP. These perinatal participants commonly described that their provider’s capacity to demonstrate empathy and validation promoted trust and feeling safe, thus encouraging disclosure.

“Right from the very beginning, I felt very comfortable with [my NSP]. She was very empathetic… It’s a human connection piece that I find some providers of mental health just don’t necessarily have.” (Perinatal_21_In-person_Non-Specialist).

Active listener

Active listening was another commonly endorsed facilitator of treatment delivery across NSP- and SP-perinatal participants (Table 3). This facilitator referred to their providers’ capacity to listen and remember details of what they shared in past sessions. Perinatal participants suggested that this allowed them to confide in and feel comfortable with their provider, which facilitated a positive rapport. Like the previous theme, perinatal participants reported this facilitator at equitable rates, irrespective of whether they received treatment from an NSP or an SP.

“[My NSP] was really great. An incredible listener. I could really tell she always remembered things from the sessions before…and I felt heard, seen, and understood.” (Perinatal_43_Telemedicine_Non-specialist).

Skilled delivery style

The third facilitator perinatal participants reported at equitable rates across NSP- and SP-perinatal participants was their providers’ perceived ability to deliver BA with skill (Table 3). This theme referred to the perinatal participants’ perception that their provider was confident and experienced in sessions, making the perinatal participants feel more at ease. These participants felt their provider appeared skilled and capable of helping them understand their own circumstances better and implement BA activities into their lives outside of treatment sessions.

“[My NSP] had a really great way of making me feel like giving context and digging into feelings around it were okay. She also brought things back around: ‘Okay, now that we fleshed that out, let’s apply it to the exercise’ so that it was more integrated.” (Perinatal_52_In-person_Non-specialist).

Created a safe space

The fourth facilitator endorsed by perinatal participants was feeling like their treatment sessions were a “safe space”. This referred to providers who created a safe environment where perinatal participants described feeling heard without judgement. Interestingly, this theme was endorsed by a larger proportion of perinatal participants who received BA from an NSP (n = 15 of 29, 51.7%) than those who received BA from an SP (n = 12 of 41, 29.3%).

“It felt like when I walked in the room, I would take a breath, and a switch would just flip and I was in the safe space now [with my NSP].” (Perinatal_18_In-person_Non-specialist)

Flexible & adaptable

The last treatment facilitator reported by perinatal participants was ensuring sessions were flexible and adaptable to their needs. Similar to the previous theme, perinatal participants who received BA from an NSP endorsed this theme more frequently (n = 14 of 29, 48.3%) relative to those who received BA from an SP (n = 8 of 41, 19.5%).

“I really liked my [NSP], the exercises we did and the fact that she tailored them for me. If something wasn’t really working, we just moved on [and she’d say,] ‘let’s find what fits.’” (Perinatal_48_In-person_Non-specialist).

Barriers of NSP relative to SP-delivered psychotherapy

When prompted about barriers, “no challenges” was the most common response across both NSP- (n = 6 of 29, 20.7%) and SP- (n = 13 of 41, 31.7%) perinatal participants. Two barriers were reported.

Rigid or inflexible BA delivery

The first barrier reported by perinatal participants was “rigid or inflexible delivery of BA” (Table 3). This referred to participants’ perceptions that their provider struggled to step outside of the step-by-step structure articulated by the BA manual. These participants remarked that they would have liked more flexibility on a week-by-week basis to meet their needs.

“I felt badly whenever [my NSP] had to redirect the conversation towards behaviour activation, the agenda that had to happen. I almost felt like I was doing something wrong.” (Perinatal_04_Telemedicine_Non-specialist).

Challenges forming a strong connection

In line with the theme of rigidity, a small portion of perinatal participants reported that they could not create a strong connection with their provider (Table 3). They noted interpersonal issues or personality differences prevented them from forming a strong connection or building rapport with their provider.

“Sometimes you have to see a few people before you find a good connection with somebody. Maybe it’s a generational difference [but] there were a couple of things about roles and family, [like] my husband’s role in helping and [my SP’s] opinions on [family] structure that were just different from what I believe.” (Perinatal_69_In-person_Specialist).

Discussion

This study involved an implementation assessment to assess the facilitators and barriers of two approaches to improving access to mental healthcare: telemedicine and task-sharing. In this study, we addressed the research-implementation gap by evaluating these innovations to inform program adoption and best practices in real-world healthcare settings38. Our study extends the quantitative findings from other clinical trials21,31, and the larger SUMMIT trial19, by highlighting the multiple facilitators and minimal barriers of telemedicine and task-sharing reported by perinatal participants and treatment providers. Our results highlight the capacity for telemedicine to mitigate the many challenges perinatal individuals and providers experience with in-person psychotherapy. Our findings suggest a strong endorsement for NSPs to deliver psychotherapy for perinatal patients in real-world settings. We contextualize our results within the broader literature below.

We found that all participant groups (perinatal participants, NSPs, and SPs) perceived telemedicine to facilitate access to care and facilitators of telemedicine outweighed those of in-person care. Irrespective of whether their provider was a specialist or non-specialist, perinatal participants who received BA via telemedicine reported the same facilitators. While the benefits of telemedicine and task-sharing are multifaceted, though it is important to consider potential caveats.

From a patient perspective, telemedicine facilitated attending therapy sessions and has the capacity to minimize gendered inequalities39,40. Congruent with existing research41,42,43 our participants highlighted that attending healthcare appointments in-person during the perinatal period is significantly more challenging than other times during the life course. Our findings highlight that many barriers to in-person care (e.g., arranging childcare) were reported as facilitators of telemedicine (e.g, alleviating childcare), which has also been shown in previous research30,44. This suggests that the perceived barriers and facilitators to treatment modality (e.g., telemedicine vs. in-person) may act on a continuum of the same theme. The convenience and flexibility of telemedicine made attending psychotherapy accessible and feasible, bridging gaps in healthcare services45,46.

Despite these benefits, research has shown that perinatal patients may require in-person sessions due to a lack of digital literacy47,48,49,50 or privacy9,51,52,53. The benefits of task-sharing and telemedicine have been found in research conducted in low-resource settings15,31,54,55, highlighting the potential for these solutions to mitigate barriers in diverse contexts. Nonetheless, research has shown that racialized perinatal women in Canada and the U.S. are more likely to face inequalities and encounter structural barriers to accessing mental healthcare32,56,55,,57. Given that some of the facilitators of telemedicine were endorsed as barriers to in-person sessions and vice versa, our findings emphasize the need for a precision medicine analysis to answer the important questions of who would benefit most from telemedicine or in-person care.

Some participants expressed the “rigid delivery style” of their treatment provider as a barrier, whereas others endorsed “flexibility” as a facilitator. This barrier was more common among those who received treatment from an NSP (n = 6 of 29, 20.7%) than an SP (n = 4 of 41, 9.8%). The implications of these findings are two-fold: (1) As demonstrated by others57, treatment providers who can be more flexible in their approach may be perceived as more effective; and (2) as NSPs become more experienced with the treatment manual, they may develop ‘therapist flexibility’ in their therapeutic approach. Future studies may benefit from examining effective approaches to teach therapist flexibility with manual adherence in task-sharing trials.

Due to many healthcare providers’ experiences serving perinatal populations, these NSPs might be particularly effective in delivering psychotherapy to perinatal individuals16. Our study suggests that healthcare providers may be optimal for delivering brief psychotherapies to perinatal patients. Nurses, midwives and other healthcare workers generally have experience with the social and physical demands of pregnancy and birth, contributing to a compassionate and holistic approach21,58. In our study, some perinatal participants expressed appreciation for their NSP’s insights and breadth of knowledge as healthcare providers regarding child development, breastfeeding challenges, and other parenting-related concerns raised in BA sessions. Hence, our findings suggest that non-mental health providers working in healthcare settings are well-suited to creating positive and trusting relationships as psychotherapy providers.

Our results suggest that NSPs use a patient-centred perspective and have relevant knowledge and experience with this patient population to contribute to a compassionate and holistic approach21,58. Our findings also suggest that NSPs working in healthcare settings are well-suited to creating positive and trusting relationships as psychotherapy providers. From a pragmatic point of view, NSP-delivered psychotherapy needs to be implemented with as minimal barriers as possible and without overburdening NSPs.

From a provider perspective, our results show that telemedicine can minimize burden on providers, such as reducing travel time to see patients. As highlighted by others59,60, providers reported that patient lateness and last-minute cancellations when conducting in-person sessions were more frustrating than telemedicine sessions because of the additional travel time required for in-person sessions. In addition, NSPs in our study emphasized that implementing telemedicine in real-world settings would allow them to balance their normal workload and deliver psychotherapy because they could conduct sessions wherever is most convenient. NSP-delivered treatment via telemedicine may improve both access and continuity in patient’s overall care20, including in community-settings. In real-world settings, there is a clear need to incorporate payment for telemedicine sessions in which the client does not attend.

From a systems perspective, telemedicine may be a cost-effective option54,61 that requires minimal resources62,63. Due to the increased uptake of telemedicine-delivered care during the COVID-19 pandemic64, healthcare systems have already shown that they can pivot to remote care11. Our study showed that telemedicine can make accessing and delivering psychotherapy easier for both patients and providers. Given the benefits and minimal resources required, healthcare institutions could benefit from implementing the straightforward solution of standardizing telemedicine-delivered psychotherapy. This will necessitate that payers appropriately reimburse telemedicine in their policies across Canadian and US healthcare systems, which would be an advantageous, cost-effective, and easily implementable shift.

Our findings also speak to the scalability of task-sharing. This approach can contribute to a collaborative stepped-care model within healthcare systems65,66 in which trained NSPs would deliver 6–8 sessions of BA to treat perinatal patients’ depressive and anxiety symptoms. Due to the finite nature of the perinatal period, this would allow patients to receive the vital care they need in a timely, cohesive manner. In the event that patients require additional mental health treatments, their care could be escalated to an SP, such as a psychiatrist59. Further, though coverage varies by region, in places like Ontario, nurse NSPs can legally deliver psychotherapy and are covered under the provincial health plan. Leveraging NSPs who are already covered to deliver psychotherapy, or behavioural interventions would potentially make NSPs a cost-friendly option for patients who otherwise could not afford to access mental healthcare services. To improve access to psychotherapy, collaboration between service providers, payers, and regulatory bodies will be required to facilitate the delivery of these effective interventions. Given that we need more mental healthcare services than ever, healthcare systems should implement task-sharing and telemedicine within a stepped-care model to better meet the needs of patients. Ultimately, telemedicine and task-sharing are straightforward solutions to improving access, with minimal barriers and numerous facilitators.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include a large, cross-national qualitative sample, which demonstrated the acceptability and feasibility of telemedicine and task-sharing, as well as the desirability among perinatal and provider participants. This implementation assessment alongside the previously published trial results19 and other sub-studies within SUMMIT11,23,66 adds depth and context to the important questions of who can provide psychotherapy treatments and how they can be provided. Another strength was its multi-stakeholder perspective, which rigorously examined a large sample of participants, including perinatal, NSP, and SP participant perspectives across the four treatment arms of the SUMMIT trial.

This study also has a few limitations. First, SUMMIT was limited to one brief, evidence-based treatment and cannot be applied to all forms of psychotherapies or participant groups. As such, exploring additional types of providers, treatments, and populations may be beneficial and warrant further study. We recommend future research focuses on a precision medicine analysis. Second, the sociodemographic characteristics of our perinatal participants sample, of whom two-thirds self-identified as white, largely educated, and in a stable relationship or married, are important to consider and may have impacted the qualitative findings. While the SUMMIT trial included a large, racially-diverse sample with equally high rates of client satisfaction, therapeutic alliance and treatment effectiveness among this racially diverse sample17,19,23, we acknowledge that perinatal populations experiencing health inequities due to their racial, educational or socio-economic background are likely to experience barriers at higher rates. Last, we interviewed perinatal participants who finished their BA treatment to inform the uptake of treatment and facilitate appropriate comparisons between treatment conditions. Future studies require further examination of perinatal patients who discontinued treatment56.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that telemedicine and task-sharing are straightforward, patient-centred solutions, which are not only acceptable but desirable. Our research provides important evidence for the uptake of these approaches in real-world healthcare settings to improve access. Maternal mental health is a global issue with cascading impacts on the overall health and well-being of society at large and needs to be addressed and met with action. By advancing telemedicine and task-sharing delivered psychotherapy, healthcare systems can reduce waitlists, alleviate burdens on SPs, and provide effective and desirable patient-centred care.

Data availability

Two years after publication, individual participant de-identified data may be available with researchers who submit a written proposal to: summittrial@sinaihealth.ca. This timeline allows the study team to collect long-term study outcomes and analyse and potentially publish the results of the secondary aims involving qualitative research. Researchers requesting data will receive a response from the study team within three business days.

References

Bauman, B. L. et al. Vital Signs: Postpartum Depressive Symptoms and Provider Discussions About Perinatal Depression - United States, 2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 69, 575–581 (2020).

Lanes, A., Kuk, J. L. & Tamim, H. Prevalence and characteristics of postpartum depression symptomatology among Canadian women: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 11, 302 (2011).

Dennis, C. L., Falah-Hassani, K. & Shiri, R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 210, 315–323 (2017).

Lu, Y. C. et al. Maternal psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic and structural changes of the human fetal brain. Commun. Med. 2, 47 (2022).

Trost, S. et al. Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 US States, 2017–2019, https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/erase-mm/data-mmrc.html (2022).

Boutin, A. et al. Database autopsy: an efficient and effective confidential enquiry into maternal deaths in Canada. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 43, 58–66. e54 (2021).

Webb, R. et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing perinatal mental health care in health and social care settings: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 8, 521–534 (2021).

Ukoha, E. P. et al. Ensuring equitable implementation of telemedicine in perinatal care. Obstet. Gynecol. 137, 487–492 (2021).

Davis, A. & Bradley, D. Telemedicine utilization and perceived quality of virtual care among pregnant and postpartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Telemed. Telecare 30, 1261–1269 (2024).

Lee, E. W., Denison, F. C., Hor, K. & Reynolds, R. M. Web-based interventions for prevention and treatment of perinatal mood disorders: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16, 38 (2016).

Singla, D. R. et al. Scaling up mental healthcare for perinatal populations: is telemedicine the answer?. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 24, 881–887 (2022).

Kakuma, R. et al. Human resources for mental health care: current situation and strategies for action. Lancet 378, 1654–1663 (2011).

van Ginneken, N. et al. Non-specialist health worker interventions for mental health care in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009149 (2011).

Padmanathan, P. & De Silva, M. J. The acceptability and feasibility of task-sharing for mental healthcare in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 97, 82–86 (2013).

Hoeft, T. J., Fortney, J. C., Patel, V. & Unützer, J. Task-sharing approaches to improve mental health care in rural and other low-resource settings: a systematic review. J. Rural Health 34, 48–62 (2018).

Singla, D. R. et al. Implementing psychological interventions through nonspecialist providers and telemedicine in high-income countries: qualitative study from a multistakeholder perspective. JMIR Ment. Health 7, e19271 (2020).

Singla, D. R. et al. Scaling Up Maternal Mental healthcare by Increasing access to Treatment (SUMMIT) through non-specialist providers and telemedicine: a study protocol for a non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. Trials 22, 186 (2021).

Pinar, S., Ersser, S., McMillan, D. & Bedford, H. A brief report informing the adaptation of a behavioural activation intervention for delivery by non-mental health specialists for the treatment of perinatal depression. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 50, 656–661 (2022).

Singla, D. R. et al. Task-sharing and telemedicine delivery of psychotherapy to treat perinatal depression: a pragmatic, noninferiority randomized trial. Nat. Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03482-w (2025).

Young, K. et al. A qualitative study on healthcare professional and patient perspectives on nurse-led virtual prostate cancer survivorship care. Commun. Med. 3, 159 (2023).

Dimidjian, S. et al. A pragmatic randomized clinical trial of behavioral activation for depressed pregnant women. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 85, 26 (2017).

Schiller, C. et al. Behavioural Activation Manual for Perinatal Women. https://thesummittrial.com/resources/bamanual-materials/ (2021).

Singla, D. R. et al. Culturally sensitive psychotherapy for perinatal women: A mixed methods study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 90, 770–786 (2022).

Andrejek, N. et al. Clinical supervision models for non-specialist providers delivering psychotherapy: a qualitative analysis. Adm Policy Ment. Health https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-025-01450-1 (2025).

Lewin, S., Glenton, C. & Oxman, A. D. Use of qualitative methods alongside randomised controlled trials of complex healthcare interventions: methodological study. BMJ 339, b3496 (2009).

Grigoropoulou, N. & Small, M. L. The data revolution in social science needs qualitative research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 904–906 (2022).

O’Mahen, H. A. & Flynn, H. A. Preferences and perceived barriers to treatment for depression during the perinatal period. J. Women’s. Health 17, 1301–1309 (2008).

Moulton, J. E., Botfield, J. R., Subasinghe, A. K., Withanage, N. N. & Mazza, D. Nurse and midwife involvement in task-sharing and telehealth service delivery models in primary care: A scoping review. J. Clin. Nurs. 33, 2971–3017 (2024).

Singla, D. R. D., Kumbakumba, E. M. & Aboud, F. E. P. Effects of a parenting intervention to address maternal psychological wellbeing and child development and growth in rural Uganda: a community-based, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob. health 3, e458–e469 (2015).

Andrejek, N. et al. Barriers and Facilitators to resuming in-person psychotherapy with perinatal patients amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a multistakeholder perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212234 (2021).

Patel, V. et al. The Healthy Activity Program (HAP), a lay counsellor-delivered brief psychological treatment for severe depression, in primary care in India: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 389, 176–185 (2017).

McKimmy, C., Levy, J., Collado, A., Pinela, K. & Dimidjian, S. The Role of Latina Peer Mentors in the Implementation of the Alma Program for Women With Perinatal Depression. Qual. Health Res. 33, 359–370 (2023).

Singla, D. R. et al. Scaling up quality-assured psychotherapy: The role of therapist competence on perinatal depression and anxiety outcomes. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 83, 101–108 (2023).

Dennis, C.-L., Grigoriadis, S., Zupancic, J., Kiss, A. & Ravitz, P. Telephone-based nurse-delivered interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression: nationwide randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 216, 189–196 (2020).

DeVellis, R. F. in Scale Development Theory and Applications Vol. 26 Applied Social Research Methods Series (Sage, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2004).

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Quali. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101 (2006).

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. in APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological Vol. 2 (eds H. Cooper et al.) 57–71 (American Psychological Association, 2012).

Kowalski, C. P. et al. Facilitating future implementation and translation to clinical practice: The Implementation Planning Assessment Tool for clinical trials. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 6, e131 (2022).

Bailey, Z. D., Feldman, J. M. & Bassett, M. T. How Structural Racism Works - Racist Policies as a Root Cause of U.S. Racial Health Inequities. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 768–773 (2021).

Vohra-Gupta, S., Petruzzi, L., Jones, C. & Cubbin, C. An Intersectional Approach to Understanding Barriers to Healthcare for Women. J. Community Health 48, 89–98 (2023).

Grzybowski, S., Stoll, K. & Kornelsen, J. Distance matters: a population based study examining access to maternity services for rural women. BMC Health Serv. Res. 11, 147 (2011).

Maldonado, L. Y., Fryer, K. E., Tucker, C. M. & Stuebe, A. M. The association between travel time and prenatal care attendance. Am. J. Perinatol. 37, 1146–1154 (2020).

Wolfe, M. K., McDonald, N. C. & Holmes, G. M. Transportation Barriers to Health Care in the United States: Findings From the National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2017. Am. J. Public Health 110, 815–822 (2020).

Hensel, J. M., Yang, R., Vigod, S. N. & Desveaux, L. Videoconferencing at home for psychotherapy in the postpartum period: Identifying drivers of successful engagement and important therapeutic conditions for meaningful use. Counsel. Psychother. Res. 21, 535–544 (2021).

Gray, M. J. et al. Provision of evidence-based therapies to rural survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault via telehealth: Treatment outcomes and clinical training benefits. Train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 9, 235–241 (2015).

Nielsen, S. Y., Sağaltıcı, E. & Demirci, O. O. Telemental health care provides much-needed support to refugees. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 751–752 (2022).

Rokicki, S., Patel, M., Suplee, P. D. & D’Oria, R. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to community-based perinatal mental health programs: results from a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 24, 1094 (2024).

DeRoche, C., Hooykaas, A., Ou, C., Charlebois, J. & King, K. Examining the gaps in perinatal mental health care: A qualitative study of the perceptions of perinatal service providers in Canada. Front Glob. Women’s. Health 4, 1027409 (2023).

Daoud, N. et al. Multiple forms of discrimination and postpartum depression among indigenous Palestinian-Arab, Jewish immigrants and non-immigrant Jewish mothers. BMC Public Health 19, 1741 (2019).

Kemet, S. et al. When I think of mental healthcare, I think of no care.” Mental Health Services as a Vital Component of Prenatal Care for Black Women. Matern Child Health J. 26, 778–787 (2022).

Jahan, N. et al. Untreated depression during pregnancy and its effect on pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review. Cureus 13, e17251 (2021).

Dowse, G. et al. Born into an isolating world: family-centred care for babies born to mothers with COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine 56, 101822 (2023).

O’Connor, A., Geraghty, S. & Doleman, D.G. & Annemarie D.L. Suicidal ideation in the perinatal period: A systematic review. Ment. Health Prev. 12, 67–75 (2018).

Mitchell, L. M., Joshi, U., Patel, V., Lu, C. & Naslund, J. A. Economic evaluations of internet-based psychological interventions for anxiety disorders and depression: a systematic review. J. Affect Disord. 284, 157–182 (2021).

Haight, S. C. et al. Racial and ethnic inequities in postpartum depressive symptoms, diagnosis, and care In 7 US Jurisdictions. Health Aff. 43, 486–495 (2024).

Lee-Carbon, L. et al. Mental health service use among pregnant and early postpartum women. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 57, 2229–2240 (2022).

Owen, J. & Hilsenroth, M. J. Treatment adherence: the importance of therapist flexibility in relation to therapy outcomes. J. Couns. Psychol. 61, 280 (2014).

Ekers, D. et al. Behavioural activation for depression; an update of meta-analysis of effectiveness and subgroup analysis. PLoS One 9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100100 (2014).

Aspvall, K. et al. Effect of an Internet-Delivered Stepped-Care Program vs In-Person cognitive behavioral therapy on obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms in children and adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 325, 1863–1873 (2021).

Cutchin, G. M. et al. A comparison of voice therapy attendance rates between in-person and telepractice. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 32, 1154–1164 (2023).

Naslund, J. A., Mitchell, L. M., Joshi, U., Nagda, D. & Lu, C. Economic evaluation and costs of telepsychiatry programmes: A systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare 28, 311–330 (2022).

Nair, U., Armfield, N. R., Chatfield, M. D. & Edirippulige, S. The effectiveness of telemedicine interventions to address maternal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Telemed. Telecare 24, 639–650 (2018).

Stentzel, U. et al. Mental health-related telemedicine interventions for pregnant women and new mothers: a systematic literature review. BMC Psychiatry 23, 292 (2023).

Smith, A. C. et al. Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J. Telemed. Telecare 26, 309–313 (2020).

Stein, A. T., Carl, E., Cuijpers, P., Karyotaki, E. & Smits, J. A. J. Looking beyond depression: a meta-analysis of the effect of behavioral activation on depression, anxiety, and activation. Psychol. Med. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291720000239 (2020).

Singla, D. R., Savel, K. A., Magidson, J. F., Vigod, S. N. & Dennis, C. L. The role of peer providers to scale up psychological treatments for perinatal populations worldwide. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 25, 735–740 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and treatment providers who participated in the SUMMIT trial and supported this research. We also thank the research staff involved in the trial. We also thank Patient-Centred Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) (award: PCS-2018C1-10621, to D.R.S.), who funded SUMMIT. The funder, PCORI, had no role in the writing or submission of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.A. and D.R.S. conceptualized the paper. N.A., Z.L., and A.C. collected and analysed the qualitative data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript, while S.S. drafted and analysed the descriptive statistics. D.R.S. provided N.A. with guidance on the interpretation of the results and drafting the manuscript. D.R.S., S.S., S.N.V., C.L.D., L.L.P., R.K.S., and S.M.B. provided inputs to the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final draft and approved the submitted version. D.R.S. is the corresponding and supervising author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Andrejek, N., Lea, Z., Cussons, A. et al. Advancing telemedicine and task-sharing to improve access to psychotherapy for perinatal populations. Commun Med 5, 406 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01099-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01099-9