Abstract

More than 2000 jurisdictions globally have declared climate emergencies. Climate emergency declarations are amongst the strongest climate change policy statements. Yet, there has been limited research focusing on what comes after a climate emergency declaration is made, and the extent to which subsequent planning includes ‘transformative’ elements. This research focuses on local governments in the State of Victoria, Australia, and analyses the emergency declarations and subsequent action plans of 39 Councils, applying an analytical framework that defines ‘transformative action’ as including mitigation and adaptation; collaboration action across and within Councils; inclusion of intersecting biodiversity emergency responses; acknowledgement of First Peoples’ knowledges and aspirations; and consideration of justice and equity. Results point to the importance of alliances and networks to push ambition and facilitate informed climate action planning. The research has potential to inform policy both locally and globally and progress understandings of the enabling conditions for transformative approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate emergency declarations are one of the strongest climate action policy statements, representing an acknowledgement of the increasingly serious scientific statements of climate change impacts, the far-reaching systemic effects of these impacts, and the urgency for taking action to mitigate the causes1. In 2007, UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon stated “this is an emergency, and for emergency situations, we need emergency action1. The first declaration of a climate emergency was made by City of Darebin, an inner-north municipality of Melbourne, Australia on 5 December 20162. Indeed, it has been suggested that local governments in the State of Victoria (where Melbourne is located) are frontrunners in climate action3. Seventy of the seventy-nine Victorian local governments are now members of one of the eight Victorian-based regional groupings of local governments focused on climate change action (Victorian Greenhouse Alliances)4. The Greenhouse Alliances are focused on advocacy, knowledge sharing, and developing and implementing ‘innovative, regional strategies and projects typically beyond the reach of individual councils4.

By September 2023, 2,343 jurisdictions in 40 countries had declared a climate emergency5. The rate of new declarations in Australia and globally has dropped in recent years (the rate of declarations appears to have peaked in 2019); reasons for this are not the focus of this research. Rather, this research is focused on what comes after the declaration of a climate emergency, and which elements of ‘transformative’ climate action are included in these post-declaration strategic planning responses.

The declaration of a climate emergency, as a strong statement of intent, has the potential to stimulate more ambitious local action, yet in some cases may act primarily as a political gesture only6. The declaration itself may have been motivated by pressure from civil society7, or may be perceived as a continuation and amplification of previous experience of environmental action within local government8. While some have raised concerns that “much of the talk about climate emergency by local government may merely be symbolic and broadly aligned with their existing local environmental and climate roles and policies9, others have suggested that emergency declarations may be “catalysing councils beyond symbolic declarations potentially opening up space for change and disruption10. This raises the question of what planning and subsequent action follows or is prompted by an emergency declaration. An analysis of urban planning documents of selected US cities, found that “although cities are beginning to address differential vulnerability and adaptive capacity, more work is required to tackle unequal socioeconomic structures and their contributions to underlying drivers of climate injustice11. Some researchers12,13 and members of civil society14 have pointed to the potential for ‘emergency’ and ‘crisis’ framings to potentially reinforce coercive and controlling state powers, potentially involving ‘temporarily suspend[ing] democracy and civil liberties’, and maintaining existing injustices. Concern has also been raised that the ‘international language’ of climate emergency may obscure or displace the existing diversity of local responses15.

Research conducted on Swedish cities that have declared a climate emergency, examined the extent to which their climate strategies exhibit a climate emergency mode16. The research applied the Climate Emergency Response Attributes Framework2 to assess the extent to which the cities’ strategies have “moved beyond business as usual to a complex emergency response for climate change16. However, the research noted that none of the cities have released climate emergency plans following their emergency declarations, and so the analysis was applied to their existing climate strategies16. Research of 344 cities in the European Cities Mission (a European Commission project aiming to deliver 100 climate neutral cities in Europe by 2030), found that “out of 63 cities with a CED [climate emergency declaration], 59 (93.7%) have developed an LCP [Local Climate Plan], which seems to suggest that the declaration of climate emergency can reach cities not previously engaged in local climate planning17. However, the analysis did not extend to examining the contents of the subsequently developed climate plans to assess their level of ambition, or how the framing of the emergency declaration was then reflected in planning for action.

Research on climate emergency declarations has analysed the processes and actors involved in the lead up to the emergency declaration, and the factors involved to trigger an emergency declaration6,7,8. There has been less focus on subsequent action planning. Indeed, “although there is near uniformity of political desire to tackle climate change, action planning is very much work in progress with tight delivery timelines, … significant divergence in approaches, and an unclear role for the citizen18. This research therefore aims to examine what comes after the declaration. The research seeks to understand whether there is evidence that an emergency declaration is followed by climate emergency planning that reflects the urgency, complexity and comprehensiveness associated with recognition and declaration of ‘emergency’ status. The research focuses on local governments in Victoria, Australia, the location of the first climate emergency declaration, and addresses the following questions:

-

Which local governments have declared climate emergencies and why?

-

Did the declaration trigger the development of a climate emergency action plan? If so, what are the key goals or objectives?

-

Which ‘transformative’ elements were included in these plans?

‘Transformative’ responses - ‘deep, broad, and rapid society-wide changes’ are increasingly called for by both academics and policy makers, yet there are few shared definitions for ‘transformation’ terminology19. ‘Transformation’ has been applied separately to climate change mitigation (emissions reductions)19; and adaptation and resilience (addressing current and future climate change impacts)20,21,22. Others have proposed a definition of ‘climate change transformation’ which includes the integration of adaptation and mitigation goals23. This latter approach has been expanded to encompass other dimensions including collaboration, integration and equity24. Catalysing more ‘transformative’ responses requires ‘a greater sense of spatial, temporal and social justice22; transformative approaches should be contextualised to effectively respond in different regions, yet there are also opportunities for guiding ‘transformative climate action across scales25.

For this research, we consider that to qualify as ‘transformative’, action plans must encompass a range of dimensions26,27, that seek to balance comprehensiveness and feasibility. ‘Transformative’ responses necessitate moving beyond ‘business-as-usual2 and require action across numerous sectors and contexts28, reinforcing the complexity of planning climate responses. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in its Sixth Assessment report, highlights the urgency for action, spanning both mitigation and adaptation; actions must be equitable and inclusive, to reduce losses and damage for people and nature28. IPCC’s recognition of both people and nature reinforces the importance of integrating biodiversity and nature with climate action29, and acknowledgement that without a shared focus on biodiversity conservation and restoration, effective climate action is not possible30,31. For jurisdictions such as local governments that are planning their climate actions and responses, managing the scope of this planning is important, and requires a balance between comprehensiveness and feasibility, targeting areas within the jurisdiction’s control. Bringing together all these considerations, we propose that the dimensions required for ‘transformative’ climate change responses include the following elements (discussed in more detail in the following paragraphs):

-

integration across the mitigation-adaptation dichotomy;

-

collaboration and integration within organisations, across sectors, and levels of government;

-

integration of climate change and biodiversity actions;

-

foregrounding and integration of First Peoples’ perspectives; and

-

integration of justice and equity considerations.

Integrating across the mitigation-adaptation dichotomy: Climate change mitigation actions focus on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, while adaptation actions focus on adapting to current and future climate change impacts. The two aspects of climate change action are often disconnected, and addressed separately in policy, strategy, action planning, and on-ground implementation32. Yet integrating across the ‘mitigation-adaptation dichotomy32 can promote the avoidance of maladaptation (adaptation that increases emissions, or short-term adaptation that hampers long term adaptation)23, as well as identifying opportunities for synergies and efficiencies.

Collaboration and integration within organisations, across sectors, and levels of government: The responsibility for planning and implementing climate actions, whether mitigation or adaptation, often spans multiple organisational policies and departments. IPCC has highlighted the importance of integrating climate change actions into “policy making, planning, and decision making across levels and sectors28,33. In a review of climate adaptation policy research33, a spectrum of approaches for ‘climate policy integration’ is identified, from coordination to harmonisation to prioritisation (the latter being the strongest approach). The elements to be considered to ensure integration include comprehensiveness, aggregation, consistency, incorporation, and prioritisation33.

Integration of climate and biodiversity action: With the recognition that climate change and biodiversity loss are coupled crises29,30, there are increasing calls for integrating climate change responses with ecological restoration responses34,35, to ensure that climate mitigation actions do not negatively impact biodiversity, and indeed provide positive biodiversity habitat benefits36. Likewise, there are opportunities for ecosystem-based approaches, such as nature-based solutions, to contribute to both mitigation and adaptation efforts37,38.

Foregrounding First Peoples’ perspectives: Planning in settler colonial countries such as Australia takes place on First Peoples’ lands39. First Peoples’ relationship with their land (‘Country’ as it is known in Australia) is characterised by responsibilities of Custodianship – reciprocal responsibilities to people, culture, and Country40,41. Climate-just approaches must foreground First Peoples’ aspirations and knowledges of their land42. IPCC recognises the essential place of First Peoples in climate planning and implementation: “Cooperation, and inclusive decision making, with Indigenous Peoples and local communities, as well as recognition of inherent rights of Indigenous Peoples, is integral to successful adaptation and mitigation”43.

Integrating justice and equity considerations: The IPCC highlights the equity and justice dimensions of both the uneven and unjust distribution of climate change impacts. In particular there is a disconnect between those responsible for emissions production and those who benefit from fossil-fuel driven development and affluence, compared to those who are most vulnerable and burdened by climate change impacts44. “Social justice and equity are core aspects of climate-resilient development pathways44. A focus on ‘climate justice’ and ‘just transitions28,45 requires consideration of integrating climate mitigation and adaptation measures that provide wider sustainable development benefits28. Fundamental to justice and equity consideration is inclusive decision-making, ensuring that local communities and civil society are able to be involved in climate planning and decision-making11. The growing ambition amongst cities to meet climate change mitigation targets for 1.5 °C needs to also acknowledge and address the justice and equity concerns that are associated with achieving the necessary action46, to ensure a just transition to a net zero future economy and society.

These elements, we argue, are the constituent parts of a comprehensive approach to transformative climate action. We apply these to form the basis for our analytical framework to assess the extent to which climate emergency action plans of Victorian local councils constitute ‘transformative’ approaches. The following section presents results of our analysis of the Victorian local councils’ climate emergency action plans, including which councils have declared an emergency, the motivators or drivers for the declarations, and the ‘transformative’ elements included in their emergency plans. The following discussion section highlights how these results relate to research from other cities and municipalities internationally and specifically considers the role of Victorian Greenhouse Alliances in promoting climate responses amongst Victorian local governments. The research methods are included at the end of the paper.

Results

This section presents the results of our analysis of which Victorian governments have declared climate emergencies, and for what reasons; whether they have subsequently developed climate emergency action plans; and how ‘transformative’ these action plans are.

Which local governments have declared climate emergencies and why?

Of the 79 local governments in the State of Victoria, 39 had declared a climate emergency by the end of November 2022. Of these, 38 local governments (or all but one) are members of one of the Victorian Regional Greenhouse Alliances. Declarations appear to have peaked during 2019; during that year 19 declarations were made (Fig. 1).

The 39 declaring Councils represent all the different local government contexts in Victoria, including metropolitan, interface (urban-rural fringe), small and large rural shires, and rural/regional cities (Fig. 2). Notably, almost half of the declarations were made by metropolitan councils (18 out of a total of 39 declarations). While these 18 councils constitute the majority of metropolitan councils (18 of the 22 metropolitan councils or 82%) the proportion of non-metropolitan councils (including interface councils, regional cities and shires) to declare an emergency sits below 50% for all other categories (17 declaring councils out of a total of 57 non-metropolitan councils).

The key drivers or motivators for the emergency declarations, as stated in Council meeting agendas and minutes, varied considerably, with the most commonly stated motivation being a local response to global climate policy negotiations, and the intention to connect global climate policy development to local action. Other motivators and drivers included climate science reports as well as observable impacts, including sea level rise and increased frequency and severity of bushfires and heatwaves. Declarations made after 2020 highlighted the severity and impacts of wildfires that had affected much of the state of Victoria during the 2019-2020 summer period47. Some declarations were framed as responses to risk assessments (that spanned social, environmental, and economic risks, as well as legal or liability concerns). Potential risks to agriculture and tourism were noted for some rural councils and regional cities.

Importantly, responding to local community pressure and advocacy was also a key motivation. Other motivators included concerns related to climate injustice (responding to the relative socio-economic disadvantage of specific local government areas); ambitious climate leadership or, on the other side of the coin, concern of reputational risk of not declaring an emergency. The key drivers and motivators are summarised in Fig. 3 (most plans identify more than one driver or motivator, hence the total number of drivers exceeds the total number of declaring councils).

Did the declaration trigger development of an action plan? What are its key goals or objectives?

Of the 39 local governments that had declared a climate emergency by the end of November 2022, 34 had subsequently developed a dedicated climate emergency action plan. Of the other five councils, three were still developing their action plans at the time of data collection (November 2022), one had included climate action in its overarching Council Plan but had not prepared a separate climate action plan, and one council was yet to develop any subsequent action plan. Of the 34 plans that were completed, 31 of these explicitly referenced ‘climate emergency’; somewhat surprisingly, three Councils’ action plans did not explicitly reference the climate emergency, or their climate emergency declaration, in their subsequent action plans.

All of the 34 completed plans were reviewed to identify their key goals and objectives. The stated goals and objectives largely fell into six categories (Table 1); many of the action plans included more than one goal or objective. Mitigation-focused goals or objectives were framed as net zero, net carbon, or emissions reductions. Adaptation focused goals or objectives were framed as resilience, resilient community, or resilient council. Examples include ‘Reduce emissions, build community resilience against the local impacts of climate change and ultimately reverse global warming’ (Bass Coast, a large rural shire), and ‘transition to a decarbonised, thriving economy and build a vibrant and resilient community’ (Greater Shepparton, regional city).

It is noteworthy that while mitigation and adaptation were amongst the most frequently mentioned goals or objectives, nonetheless at least half the plans did not include a goal or objective related to these specific themes, with many of these plans instead focused on more generalised goals or objectives of thriving communities, liveable cities, and sustainable environments. Examples included ‘A thriving community of empowered citizens working together for an inclusive and sustainable future’ (Glen Eira, a metropolitan council); and ‘Thriving, safe, just, and prosperous local communities’ (Hepburn, a small rural shire). Another group of objectives or goals focused on mobilising council, community or ‘collective’ action. Examples included ‘We have the capacity to achieve our aspirations, and inspire others along the way’ (Boroondara, a metropolitan Council); ‘Mobilise and enable the community to act on climate change’ (Indigo, a small rural shire); and ‘leverage Council resources and spheres of influence to support and accelerate our community response’ (Kingston, a metropolitan council). Other themes included ‘Guided by science’ (Queenscliffe, a small rural shire); ‘living within planetary boundaries’ (Hepburn, a small rural shire); and ‘pushing for urgent change and changing the way we live and work’ (Yarra, a metropolitan council).

Which transformative elements are included in climate plans?

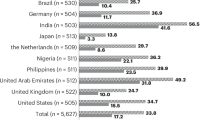

All completed and draft plans were analysed to assess the inclusion and relative frequency of the key dimensions of transformative climate action: mitigation; adaptation; collaboration; biodiversity; Indigenous/First Peoples’ perspectives; and justice and equity considerations. All text for each Council’s climate plan was included in the analysis (not just the key goals or objectives, that were the focus of the previous section of this research). The relative frequency, rather than absolute frequency or total number of inclusions, was analysed, so that shorter plans (with fewer words) could be effectively compared with longer plans. The relative frequency of terms in each of the climate action plans is represented in Fig. 4.

Of the 38 plans analysed, 30 plans included at least one reference to all dimensions of transformative climate action. Of the remaining eight plans, four plans included at least one reference to all dimensions except Indigenous/First Peoples’ perspectives; three plans included at least one reference to all dimensions except justice and equity considerations; and one plan did not include Indigenous/First Peoples’ perspectives or justice and equity considerations.

Of the 38 plans, 36 plans’ relative frequency of mitigation and adaptation dimensions exceeded the relative frequency of the other dimensions. Of the other 2 plans, one showed a greater frequency of Indigenous/First Peoples’ perspectives than mitigation; and the other showed a greater frequency of both Indigenous/First Peoples’ perspectives and justice and equity considerations than mitigation. However, for most plans, mitigation frequency exceeded 20% (34 plans), and adaptation frequency exceeded 20% (34 plans). Likewise, for most plans the other four dimensions were less than 20% each (37 plans for collaboration; 37 plans for biodiversity; 36 plans for Indigenous/First Peoples; and 37 plans for justice and equity considerations).

The results reflect that local governments are actively engaged in planning for climate mitigation and adaptation actions, which are broadly understood to form the basic and ‘universal’ elements of climate action planning48,49,50,51. Examples include Bass Coast Shire’s goals of ‘zero net emissions by 2030 and to respond to climate impacts already being felt and projected in the future’. Darebin’s plan states that core goals include ‘to provide maximum protection for the community of Darebin and for people, civilisation and species globally, especially the most vulnerable; … to protect people, species and civilisation from near-term dangerous temperatures, while zero emission and carbon dioxide drawdown strategies are being enacted; to enable our community to be resilient in the face of any unavoidable dangerous climate impacts’. Port Phillip’s plan states ‘Council declared a climate emergency in 2019, recognising that climate change is a global challenge, and everyone must play their part. We are reducing our own emissions and preparing our City and community for a changing environment’. These quotes highlight the centrality of mitigation and adaptation in most plans, as well as recognition of the need for collaboration between local government and community, other levels of government and business.

It is notable that 30 of the 38 plans included at least one reference to all the dimensions of transformative climate action, suggesting that the local governments that have made emergency declarations have also developed a relatively comprehensive and sophisticated approach to climate action planning that integrates at least some mention of a broad range of transformative dimensions. For example, Hepburn’s plan includes an opening statement on ‘Caring for and Healing Country’ from the CEO of the Djaara (Dja Dja Wurrung People) Traditional Owners Corporation, that states ‘we have a duty to care for our Country and feel ashamed and sad that it is currently suffering. When the Country suffers, we suffer. … [this plan] presents an important opportunity to walk together and heal Country’. City of Greater Geelong’s Plan Executive Summary states that ‘Climate change is not solely an environmental issue. It has implications for every aspect of how we live – our social systems, economic systems and the natural systems upon which we all depend. We need to act quickly, decisively and collaboratively to make a difference’. However, mitigation and adaptation still dominate the majority of the plans analysed, with considerably less coverage of the other dimensions.

Discussion

Climate emergency declarations have been an important focus for community advocacy and mobilisation. To ensure that a declaration is more than grandstanding, hollow symbolism or greenwashing10, some form of action plan development, followed by associated implementation of these plans is necessary. Almost all Victorian Councils that have declared emergencies, have since developed climate action plans, demonstrating a commitment to moving from declaration to planning for climate action. Many of the plans define ambitious targets and whole-of-council responses. Collaboration and intermediation are important – these are acknowledged in both the emergency declarations themselves, and in the subsequent action plans. Collaboration includes efforts across Councils as well as between Councils and their local communities, while intermediation includes linking between councils and other organisations, often through membership of a local government or climate change alliance or network52,53.

Membership and involvement in alliances and partnerships appears to play a role in raising ambition and informing the development of subsequent action plans. The global climate emergency declaration database (https://climateemergencydeclaration.org/) highlights membership of a range of alliances including C40, ICLEI, Global Covenant of Mayors, Under2, Cities Power Partnership, Race to Zero, and the Fossil Fuel Non-proliferation Treaty. Research on regional alliances and networks has pointed to the processes and mechanisms by which these networks can extend or ‘scale up’ action17,53,54,55,56. For example, a study that compared adaptation actions at the local and regional scale in Melbourne Australia and Gothenburg Sweden, found that regional scale adaptation can ‘identify, connect, and amplify small-scale (local) wins and utilize this collective body of knowledge to challenge and advocate57.

In Victoria, many local governments are members of one of the 8 Victorian Greenhouse Alliances, which provide forums for local government members’ information sharing, collaboration, and project implementation4. The first regional greenhouse alliance formed in 2000; by 2018 there were 8 regional alliances with membership including 70 of the 79 Victorian local governments4. The minutes of the council meetings at which the emergency declarations were made, as well as the subsequent emergency action plans, recorded the vital roles that both global and local/regional partnerships, networks, and alliances played in accelerating climate action within the declaring local governments. Terms such as knowledge sharing, capacity building, competition, and local climate leadership were common within most of the action plans. Councils with limited capacity to tackle the climate emergency (including smaller councils and rural shires), were keen for support, while the highly active and well-resourced councils (often larger metropolitan councils) saw alliance membership as an additional opportunity to demonstrate leadership. Arguably, the alliances create an ‘implementation ecosystem’ or enabling environment58 that both informs climate action planning and encourages ambitious action through ‘friendly competition’ between alliance members. There are opportunities for further research to elaborate the roles of regional alliances and collaborations in climate action planning, implementation and evaluation.

Emergency declarations have been framed as public and ambitious commitments to increased climate change action, potentially pushing both local accountability and local influence on national and global climate policy decision-making59. Transformative action has been contrasted with business-as-usual and incremental approaches60,61; in this research we have applied a framework for ‘transformative’ elements that highlights the range of dimensions that need to be included. This provides a contribution towards tangible guidance for climate emergency action plan development. Importantly, while the plans analysed in this research included a range of ‘transformative’ elements, plans must be implemented for results to be achieved, and a key challenge in moving from ambition to action is ensuring adequate allocation of funding and resources to enable this shift62. This is beyond the scope of the current research, but further research that evaluates the effectiveness of implementation of climate action plans would be highly relevant.

While an emergency declaration is seen as a key statement of ambition and commitment, it is the subsequent framing and implementation of actions that constitutes and demonstrates the extent to which this can be considered transformative action. This research has focused on the development and content of climate action plans following the emergency declaration; further research is required to assess whether a climate emergency declaration has indeed generated increased implementation of transformative action and responses. Recent research has examined the adequacy of mitigation targets in built environment policies across Federal, State and local government in the City of Melbourne63; future research could apply this approach to an analysis of the climate emergency plans identified in this research to assess adequacy and ambition. It would also be informative to examine more recent emergency declarations and associated plans to assess whether approaches have evolved or strengthened over time. Future research could also consider whether there are differences between planning and implementation based on size and location (urban-rural context) of the local governments, and whether there are differences in content, ambition and implementation between declaring and non-declaring councils.

A focus on integrating all elements of transformative action into subsequent planning and implementation is essential to ensure that the transition to a safe climate future is also a just climate future28, and that ‘inequalities are not exacerbated by climate action64. This research has contributed to research in this area by identifying five key elements for transformative climate responses; and by bringing together an important data set – Victorian local governments that have declared a climate emergency. Victoria is a significant location, being the state in which the first emergency declaration in the world was made in December 2016 by Darebin City Council. To date, Victorian Councils that have declared an emergency appear to be reinforcing the importance of collaboration, agency, and empowerment for local communities, and as such aiming to foreground approaches to just, comprehensive, and effective climate action. Reviewing the implementation of the climate action plans in future will likely prove instructive.

Methods

This qualitative research focused on examining climate emergency declarations and subsequent climate action plans in Victorian local governments. The State of Victoria, in south-eastern Australia includes 79 local governments, including the metropolitan-based City of Darebin, which was the first jurisdiction in the world to declare a climate emergency, in December 2016. The research brought together data from civil society and local government online published meeting agendas, minutes, reports and strategies. These were analysed using directed content analysis to generate research findings. Analysis was informed by the key principles and research to date on climate emergency declarations and on climate action planning, which was discussed in the Introduction.

Firstly, to identify which of Victoria’s 79 local governments had declared a climate emergency by the end of November 2022, data was accessed from the Climate Emergency Declaration global database (https://climateemergencydeclaration.org/). This database and website are created and maintained by a collaboration of Australian-based civil society climate activist groups (https://climateemergencydeclaration.org/about/). Following the identification of which local governments had declared a climate emergency, the meeting agendas, meeting minutes, and Council reports were downloaded from each of the 39 declaring Councils’ respective website. These documents were used to identify the motivation for declaring a climate emergency, and the stated wording of the emergency declaration.

To address the second research question, did the emergency declaration trigger the development of a climate emergency action plan, the websites of the 39 Victorian Councils that had declared a climate emergency were searched to discover whether a climate change action plan had been developed following the declaration, and whether the action plan specifically referenced the emergency declaration. Where an action plan had been published (34 published plans, that include 3 draft plans and 31 final plans), the overarching objective, aim or goal was recorded.

To address the third question, which ‘transformative’ elements were included, we undertook content analysis of the most recent climate plans of declaring councils (38 in total, see Table 2) using NVivo, a software program for qualitative data analysis. (For the 4 councils where a draft or final plan had not been published, the Council’s key strategic plan was analysed).

First, each plan was read in its entirety to develop a general understanding of the content. The plans were then uploaded into NVivo. For the ‘text’ search function, 22 terms (including stemmed words, see Table 3) were used across the transformative concepts:

-

Explicit inclusion of both mitigation and adaptation

-

Collaboration across Council, including a suite of actions across whole of Council, and collaboration between departments within Council

-

Recognition or inclusion of intersecting biodiversity emergency

-

Indigenous knowledges, perspectives and aspirations

-

Social justice

The list of terms was developed based on our literature review and was adapted through multiple rounds of coding the plans to determine the most appropriate terms. Each term was input into the ‘text search’ one at a time. With each search, the query results were reviewed to determine the location, context, and use of the word in each plan. The frequency of the terms was recorded for each transformative category for each local government. Analysing the frequency of terms is used to identify trends, priorities, and prevalence of words and phrases65. This analysis provided us with data across the 38 plans, as well as for the individual plans. Analysis and comparison of the search findings focused on the relative proportional inclusion of terms, in the form of percentages, rather than absolute number of term inclusions (so that shorter plans were not disproportionally impacted compared with longer plans).

Data availability

Data available on request.

References

Spratt, D. & Sutton, P. Climate Code Red: The Case for Emergency Action. (Scribe Publications, 2008).

Davidson, K. et al. The making of a climate emergency response: examining the attributes of climate emergency plans. Urban Clim. 33, 100666 (2020).

Doyon, A., Moore, T., Moloney, S. & Hurley, J Evaluating evolving experiments: the case of local government action to implement ecological sustainable design. J. Environ. Planning Management, 1–22 https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2019.1702512 (2020).

Law, R. Regional Victorian Greenhouse Alliances: local governments working together on climate change. (Victorian Greenhouse Alliances, Victoria, 2018).

Climate Emergency Declaration. Climate Emergency Declaration (CED) places, https://www.cedamia.org/ (2023).

Howarth, C., Lane, M. & Fankhauser, S. What next for local government climate emergency declarations? The gap between rhetoric and action. Climatic Change 167 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03147-4 (2021).

Harvey-Scholes, C., Mitchell, C., Britton, J. & Lowes, R. Citizen policy entrepreneurship in UK local government climate emergency declarations. Rev. Policy Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12522 (2022).

Ruiz-Campillo, X., Broto, V. C. & Westman, L. Motivations and intended outcomes in local governments’ declarations of climate emergency. Politics Gov. 9, 17–28 (2021).

Chou, M. Australian local governments and climate emergency declarations: Reviewing local government practice. Aust. J. Public Adm. 80, 613–623 (2021).

Greenfield, A., Moloney, S. & Granberg, M. Climate Emergencies in Australian Local Governments: From Symbolic Act to Disrupting the Status Quo? Climate 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/cli10030038 (2022).

Chu, E. K. & Cannon, C. E. Equity, inclusion, and justice as criteria for decision-making on climate adaptation in cities. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustainability 51, 85–94 (2021).

Osborne, N. & Carlson, A. Against a nation state of emergency: how climate emergency politics can undermine climate justice. npj Clim. Action 2, 46 (2023).

Cretney, R. & Nissen, S. Emergent Spaces of Emergency Claims: Possibilities and Contestation in a National Climate Emergency Declaration. Antipode https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12843 (2022).

Hollo, T. What does ‘climate emergency’ mean? https://www.greeninstitute.org.au/what-does-climate-emergency-action-mean/ (2020).

Nissen, S. & Cretney, R. Retrofitting an emergency approach to the climate crisis: A study of two climate emergency declarations in Aotearoa New Zealand. Environ. Plan. C: Politics Space 40, 340–356 (2022).

Henman, J., Shabb, K. & McCormick, K. Slow Emergency but Urgent Action? Exploring the impact of municipal climate emergency statements in Sweden. Urban Climate 49 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2023.101575 (2023).

Salvia, M. et al. Key dimensions of cities’ engagement in the transition to climate neutrality. J. Environ. Management 344, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118519 (2023).

Gudde, P., Oakes, J., Cochrane, P., Caldwell, N. & Bury, N. The role of UK local government in delivering on net zero carbon commitments: you’ve declared a Climate Emergency, so what’s the plan? Energy Policy 154 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112245 (2021).

Moore, B. et al. Transformations for climate change mitigation: A systematic review of terminology, concepts, and characteristics. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 12 https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.738 (2021).

Castán Broto, V., Olazabal, M. & Ziervogel, G. Disrupting the imaginaries of urban action to deliver just adaptation. Build. Cities 5, 199–214 (2024).

Filho, W. L. et al. Transformative adaptation as a sustainable response to climate change: insights from large-scale case studies. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 27, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-022-09997-2 (2022).

O’Hare, P. Not ‘just’ climate adaptation—towards progressive urban resilience. Humanities Soc. Sci. Commun. 12, 260 (2025).

Hurlimann, A. C., Moosavi, S. & Browne, G. R. Climate change transformation: a definition and typology to guide decision making in urban environments. Sustain. Cities Soc. 70, 102890 (2021).

Hurlimann, A. et al. Integrating Climate Change Action Across the Built Environment: A Guide for Transformative Action. (The University of Melbourne, Parkville, 2025).

Hölscher, K., Frantzeskaki, N., Jäger, J., Holman, I. & Pedde, S. Co-producing transformative visions for Europe in 2100: A multi-scale approach to orientate transformations under climate change. Futures 143, 103025 (2022).

Bush, J. & Doyon, A. Tackling intersecting climate change and biodiversity emergencies: opportunities for sustainability transitions research. Environ. Innov. Societal Transit. 41, 57–59 (2021).

Bush, J. & Doyon, A. Planning a just nature-based city: Listening for the voice of an urban river. Environ. Sci. Policy 143, 55–63 (2023).

IPCC. Synthesis Report of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6). Summary for Policymakers. (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2023).

UNEP. Making Peace with Nature: A scientific blueprint to tackle the climate, biodiversity and pollution emergencies, (United Nations Environment Program, Nairobi, 2021).

Pörtner, H. O. et al. IPBES-IPCC co-sponsored workshop report on biodiversity and climate change. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4659158 (2021).

WWF. Climate, nature and our 1.5°C future. A synthesis of IPCC and IPBES reports. (World Wildlife Fund, Switzerland, 2019).

Wamsler, C. & Pauleit, S. Making headway in climate policy mainstreaming and ecosystem-based adaptation: two pioneering countries, different pathways, one goal. Climatic Change 137, 71–87 (2016).

Braunschweiger, D. & Pütz, M. Climate adaptation in practice: how mainstreaming strategies matter for policy integration. Environ. Policy Gov. 31, 361–373 (2021).

Pörtner, H.-O. et al. Overcoming the coupled climate and biodiversity crises and their societal impacts. Science 380, eabl4881 (2023).

Smith, P. et al. How do we best synergize climate mitigation actions to co-benefit biodiversity?. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 2555–2577 (2022).

Gorman, C. E. et al. Reconciling climate action with the need for biodiversity protection, restoration and rehabilitation. Sci. Total Environ. 857, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159316 (2023).

Pasimeni, M. R., Valente, D., Zurlini, G. & Petrosillo, I. The interplay between urban mitigation and adaptation strategies to face climate change in two European countries. Environ. Sci. Policy 95, 20–27 (2019).

Seddon, N. Harnessing the potential of nature-based solutions for mitigating and adapting to climate change. Science 376, 1410–1416 (2022).

Jackson, S., Porter, L. & Johnson, L. C. Planning in Indigenous Australia: from imperial foundations to postcolonial futures. (Routledge, 2017).

Cumpston, Z. To address the ecological crisis, Aboriginal peoples must be restored as custodians of Country. The Conversation https://theconversation.com/to-address-the-ecological-crisis-aboriginal-peoples-must-be-restored-as-custodians-of-country-108594 (2020).

Langton, M. The Welcome to Country Handbook : A Guide to Indigenous Australia. (Hardie Grant Explore, 2023).

Bush, J., West, K. & Miller, M. in Planning in an uncanny world: Australian Urban Planning in International Context (eds N. A.Phelps, J.Bush, & A.Hurlimann) (Routledge, 2022).

IPCC. AR6 Climate Change 2022. Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Summary for Policymakers. (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2022).

IPCC. Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC special report. (Cambridge University Press, UK, 2018).

Rockström, J. et al. Safe and just Earth system boundaries. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06083-8 (2023).

Chu, E., Schenk, T. & Patterson, J. The dilemmas of citizen inclusion in urban planning and governance to enable a 1.5 °C climate change scenario. Urban Plan. 3, 128–140 (2018).

Vardoulakis, S., Marks, G. & Abramson, M. J. Lessons learned from the Australian bushfires: climate change, air pollution, and public health. JAMA Intern. Med. 180, 635–636 (2020).

Castán Broto, V. & Bulkeley, H. A survey of urban climate change experiments in 100 cities. Glob. Environ. Change 23, 92–102 (2013).

Davoudi, S., Crawford, J. & Mehmood, A. Planning for climate change. Strategies for mitigation and adaptation for spatial planners. (Earthscan, 2009).

Howarth, C. & Robinson, E. J. Z. Effective climate action must integrate climate adaptation and mitigation. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 300–301 (2024).

Hurlimann, A., Moosavi, S. & Browne, G. R. Urban planning policy must do more to integrate climate change adaptation and mitigation actions. Land Use Policy, 105188 (2021).

Horne, R. & Moloney, S. Urban low carbon transitions: institution-building and prospects for interventions in social practice. Eur. Plan. Stud. 27, 336–354 (2019).

Moloney, S., Bosomworth, K. & Coffey, B. in Urban Sustainability Transitions: Australian Cases - International Perspectives (eds Moore, T., Haan, F. D., Horne, R. & Gleeson, B J) Ch. 6, 91-108 (Springer Singapore, 2018).

Hölscher, K., Frantzeskaki, N. & Loorbach, D. Steering transformations under climate change: capacities for transformative climate governance and the case of Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Regional Environ. Change, 1–15 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-018-1329-3 (2018).

Moloney, S. & Fünfgeld, H. Emergent processes of adaptive capacity building: local government climate change alliances and networks in Melbourne. Urban Clim. 14, 30–40 (2015).

Salvia, M. et al. Understanding the motivations and implications of climate emergency declarations in cities: The case of Italy. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 178, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.113236 (2023).

Granberg, M., Bosomworth, K., Moloney, S., Kristianssen, A. C. & Fünfgeld, H. Regional-scale governance and planning support transformative adaptation: a study of two places. Sustainability (Switzerland) 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/su11246978 (2019).

Moloney, S. & Doyon, A. The Resilient Melbourne experiment: Analyzing the conditions for transformative urban resilience implementation. Cities 110, 103017 (2021).

Kythreotis, A. P., Howarth, C., Mercer, T. G., Awcock, H. & Jonas, A. E. G. Re-evaluating the changing geographies of climate activism and the state in the post-climate emergency era in the build-up to COP26. J. Br. Acad. 9, 69–93 (2021).

Heikkinen, M., Ylä-Anttila, T. & Juhola, S. Incremental, reformistic or transformational: what kind of change do C40 cities advocate to deal with climate change?. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 21, 90–103 (2019).

Hopwood, B., Mellor, M. & O’Brien, G. Sustainable development: mapping different approaches. Sustain. Dev. 13, 38–52 (2005).

Dyson, J. & Harvey-Scholes, C. in Addressing the Climate Crisis: Local action in theory and practice (eds Howarth C., Lane M., & Slevin A) 51-61 (Springer International Publishing, 2022).

Hurlimann, A., Browne, G. R., March, A., Moosavi, S. & Bush, J. Translating global emission reduction goals into built environment policy instruments: an ambitious yet inadequate policy portfolio for Victoria, Australia. Climate Policy, 1–14 https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2025.2459319 (2025).

Ross, A., Van Alstine, J., Cotton, M. & Middlemiss, L. Deliberative democracy and environmental justice: evaluating the role of citizens’ juries in urban climate governance. Local Environ. 26, 1512–1531 (2021).

MacCallum, D., Babb, C. & Curtis, C. Doing research in urban and regional planning: lessons in practical methods. (Routledge, 2019).

Acknowledgements

Research assistance was provided by Haritima Bahuguna and Ashley Armitage.Thanks to Sally MacAdams, Coordinator of Climate Emergency Australia, for context and references on local government emergency action plan guides and resources. Judy Bush is the recipient of an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award DE240100699 (2024–2027).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.B. and A.D.: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. Judy Bush was previously employed by one of the regional greenhouse alliances discussed in the article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bush, J., Doyon, A. Climate emergency declarations by local governments– what comes next?. npj Clim. Action 4, 44 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-025-00253-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-025-00253-2

This article is cited by

-

Crisis as catalyst? Exploring cities’ climate emergency declarations for transformative urban governance

Urban Transformations (2025)