Abstract

Some climate activists use nonviolent civil disobedience (NVCD) to protest the slow pace of climate policy action. Civil disobedience theorists posit that building a critical mass of support for and participation in NVCD increases the likelihood of policy success. Here we investigate predictors of public support for and personal willingness to engage in NVCD using data from a nationally representative survey of U.S. adults (n = 1303). Linear regression analysis revealed the following significant predictors of public willingness to support and engage in NVCD: collective efficacy; anger; identification with climate activists; descriptive norms and exposure to liberal news media. Similarly, all these variables were significant in the relative weight analysis. These findings provide theoretical and practical insights into the role of NVCD in the climate movement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change, which is caused primarily by the burning of fossil fuels, is an urgent global threat with far-reaching effects on human life and ecosystems. Despite decades of warnings by prominent scientific bodies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), including the recent Sixth Assessment (AR6) Synthesis Report1, fossil fuel production and consumption continues largely unabated worldwide, with the U.S. being one of the largest contributors to climate change as a result of its heavy production and use of fossil fuels2.

Some climate activists have responded to the slow pace of policy action by turning to nonviolent civil disobedience (NVCD)—including blockades, tree-sitting, symbolic defacement of art in museums, boycotts, and sit-ins (in some cases, breaking laws and inviting arrest)—to draw attention to the climate crisis and motivate the public, policymakers, and governments to act with urgency3,4.

NVCD can be defined in different ways. Social justice theorist John Rawls defines NVCD as “a public, nonviolent, conscientious yet political act contrary to law usually done to bring about a change in the law or policies of the government”5. In contrast, our study adopted a broader operationalization based on Chenoweth’s definition, which is “a form of collective action that seeks to affect the political, social, or economic status quo without using violence or the threat of violence against people to do so”6. This broader definition informed our operationalization of NVCD. An example of climate-related NVCD happened on April 6, 2022, when a coalition of climate scientists known as Scientist Rebellion coordinated acts of NVCD in 25 nations to highlight climate injustice and the ecological crisis7.

Prior research suggests that people are more likely to support and engage in NVCD when: (1) they feel a great injustice is happening, and (2) they feel there has been a failure in policy or government that must be redressed8. Prior research has found that support for organizations that engage in NVCD in defense of the climate is largely restricted to segments of the public characterized as Alarmed or Concerned about climate change9,10 and that about half of the people who support NVCD are willing to personally participate in it.

Prior research has also examined predictors of climate civil disobedience in various populations—including sentiment pools11 and Norwegians12. Other studies have examined predictors of understanding civil disobedience in Hong Kong’s political context13, and attitudes towards civil disobedience14—however, to our knowledge, there has been no prior research on the factors that predict willingness of the U.S. public to support and engage in climate-related NVCD. Here, we used data on a variety of theoretically relevant variables collected in a nationally representative survey of U.S. adults to explore predictors of public willingness to support and engage in NVCD against corporate or government activities that make global warming worse.

Drawing on prior research, our study examines a variety of potential predictors of willingness to support and engage in climate-related NVCD including: political party identification, media exposure, climate beliefs and emotions (i.e., belief certainty, human causation, risk perception, collective efficacy, hope, anger, and worry); descriptive norms; and identification with climate activists15,16,17,18. Below, we discuss the differences between climate-related NVCD and non-climate-related NVCD, as well as outline the theoretical basis for exploring these potential predictors of NVCD.

Non-normative collective action questions the legitimacy of the existing social system and seeks to redefine the boundaries of what is deemed ‘right’, ‘legal’, or acceptable19. Non-normative collective actions, such as climate-related NVCD, play an important role in many social movements by challenging established norms and agitating for change. Prior research emphasizes the psychological underpinnings of support for and engagement in more radical forms of collective action, highlighting the importance of antecedents such as collective efficacy, anger, and identification in driving participation20. Individuals demonstrate a willingness to confront injustices and disrupt the status quo, ultimately aiming to raise awareness and prompt societal transformation by engaging in NVCD. Climate-related NVCD, in particular, can draw attention to the issue and push for policy changes that address the urgent threat of climate change.

Climate-related NVCD shares similarities with NVCD in other contexts, such as those for civil rights or against tyrannous regimes, yet also presents unique aspects. Climate activists, like those in the civil rights movement, abortion-rights and pro-life movements, the women’s suffrage movement, and Black Lives Matter are driven by a profound sense of injustice and the urgent need for systemic change21,22,23,24,25,26. However, unlike civil disobedience movements that address specific national or local issues, such as civil rights or abortion, climate-related NVCD is driven by the urgent need to decrease carbon emissions, as well as address a planetary crisis23,27. Climate change is a global issue that transcends local or national boundaries28,29,30, affecting economies, communities, and ecosystems worldwide. This global dimension necessitates a broader coalition of activists and stakeholders, fostering international solidarity and collaboration.

Further, climate change is increasingly perceived as an existential threat24,31, a characterization that sets it apart from other social and political issues. Also, climate change, as a global health emergency and ethical crisis32,33, necessitates well-planned climate action to enhance health, equity, and human rights34,35,36,37,38. Faced with persistent inaction, some citizens are resorting to NVCD in an effort to compel governments to take stronger measures4. Therefore, participants in climate-related NVCD often act out of a profound sense of duty to protect future generations and preserve the planet, a motivation that is both deeply personal and universally resonant39.

These distinctive features—global scope and existential urgency—position climate-related NVCD within a unique context that blends elements of traditional civil disobedience with a broader environmental and ethical concern. By situating climate-related civil disobedience within the NVCD literature, we seek to contribute to understanding how urgent environmental concerns drive collective action and how these movements can influence policy and public behavior39. Given that research on climate-related civil disobedience is relatively new, this study aims to explore what factors predict public support and willingness to engage in such activism, and how the predictors of climate NVCD are similar or different than NVCD in other social movements. Therefore, the study of climate-related civil disobedience not only adds to the literature on civil disobedience but also engages prior research on climate change beliefs, attitudes, and behavior, investigating the evolving nature of public protest in response to global ecological challenges. Considering both the general literature on NVCD, and the climate-specific context of NVCD in support of climate action, we examine potential predictors of climate NVCD below.

Prior studies have found that political party identification can be an essential identity40,41,42,43 that influences how Americans evaluate policy44. Political party identification and ideology also impact public opinions on climate change—a highly politicized issue in the United States45,46. This polarization has resulted in strong associations between party identification, political ideology, and climate perspectives, including issue engagement, support for climate aid, and policy support46,47,48,49,50,51. Indeed, political ideology is one of the most consistent predictors of climate belief in the U.S.52. For example, in the U.S., Republicans are less likely than Democrats to believe that global warming is happening and support government action on climate change48. Furthermore, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to support and engage in social movements such as civil disobedience and climate protests11,53. Our analysis included party identification rather than political ideology for various conceptual and methodological reasons. Political parties play a key role in American politics, with many people more likely to accept party-preferred policies54,55. In addition, based on 40 years of data from the American National Election Studies, researchers discovered that 27.5% of Americans declined to identify their political ideology when given the opportunity, whereas only 4.9% declined to identify themselves on partisan lines56. Additionally, methodologically, we aimed to minimize multicollinearity in our models, and party identification and political ideology were anticipated to be highly correlated when we conceptualized the analysis (as was confirmed when the analyses were conducted). Therefore, we hypothesize:

H1: Democrats will be more likely than Republicans to support and be willing to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience in defense of the climate.

For members of the public, news media are an essential source of information about global warming. Beyond merely informing, news media coverage influences both public opinion and political agendas through an agenda-setting process whereby the amount and framing of news coverage makes the issue more salient and suggests its relative importance57. Indeed, exposure to news reporting on climate change is associated with the importance people accord global warming as a voting issue58.

The use of partisan media influences political participation59. Prior studies indicate that cable news networks (i.e., Fox News, MSNBC) take a more obvious partisan posture than traditional news networks to align with and influence the ideological inclinations of their audiences60,61. For instance, as a conservative news outlet, Fox News coverage of global warming tends to be dismissive of global warming, encouraging viewers to doubt climate scientists and climate change62,63. In contrast, as a liberal news outlet, MSNBC’s coverage of global warming encourages viewers to engage with the facts and to be critical of conservative opposition to climate science and policy64.

Coverage of global warming on mainstream news networks (i.e., ABC, CBS, NBC) is both less partisan than coverage on Fox News and MSNBC65 and more fact-based than Fox News62. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H2a: Exposure to liberal news sources will be positively associated with support for and willingness to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience in defense of the climate.

H2b: Exposure to conservative news sources will be negatively associated with support and willingness to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience in defense of the climate.

H2c: Exposure to mainstream news sources will be positively associated with support for and willingness to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience in defense of the climate.

Previous studies find that key climate beliefs—that global warming is real, human-caused, and harmful—are related to climate policy and global warming political activism16,17,18,46,66,67. Moreover, perceived risk and collective efficacy are associated with climate activism, political activism, pro-environmental behavior, and policy support16,45,68,69,70,71. While these studies predicted more general forms of climate or environmental activism16,45,71, we anticipate that these key climate beliefs will also predict NVCD.

Belief certainty reflects the extent to which people are convinced that global warming is, or is not, happening16,17,18,72. Prior work has found that individuals who are more certain global warming is happening are more likely to support and engage in personal mitigation behaviors, political behavior, climate adaptation and mitigation, and climate policy47,72,73,74. Therefore, we hypothesize :

H3a: Greater belief certainty that global warming is happening will be positively associated with support for and willingness to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience in defense of the climate.

There is widespread consensus among scientists that carbon emissions from human activities are the primary cause of global warming75,76,77. The belief that global warming is human-caused is a key predictor of individuals’ support for and engagement in global warming political activism, climate adaptation and mitigation, climate policy, societal action, individual climate-friendly action, and climate change scientific agreement16,47,72,73,74,78. Hence, it is likely that the belief that global warming is human-caused will also be related to willingness to support and engage in nonviolent civil disobedience against corporate or government activities making global warming worse.

H3b: Belief that global warming is human-caused will be positively associated with support for and willingness to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience in defense of the climate.

Multiple studies have found that global warming risk perceptions are associated with greater support for climate policies and willingness to engage in climate activism and pro-environmental behaviors to help mitigate global warming16,45,68,79,80,81,82. Hence, we hypothesize:

H3c: Greater perceived risk will be positively associated with support for and willingness to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience in defense of the climate.

Social cognitive theory posits that collective efficacy—the belief in a group’s ability “to organize and execute the courses of action required to manage prospective situations”—strongly “influences how people think, feel, motivate themselves, and act” as a group83 (p. 2). Furthermore, several studies have found that perceived collective efficacy is a significant predictor of climate protest participation, political behavior, climate change mitigation intention, climate-related water conservation, climate policy, and pro-environmental behavior16,69,84,85,86,87. Hence, we hypothesize:

H3d: Perceived collective efficacy will be positively associated with support for and willingness to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience in defense of the climate.

Cognitive appraisal theory and the functional approach to emotion suggest that certain discrete emotions motivate behavior88,89. Anger, worry, and hope are discrete emotions in that they have “unique appraisal patterns, motivational functions, and behavioral associations”90 (p. 290). Past research indicates that anger, worry, and hope predict global warming policy support and willingness to engage in climate activism91,92,93.

Lazarus94 defines hope as “fearing the worst but yearning for better and believing the wished-for improvement is possible” (p. 16). Hope is a positive emotion associated with global warming95,96. For instance, several studies have found that feeling hopeful about global warming is a key predictor of people’s support for and engagement in climate-related activism and social movements97,98,99,100,101,102,103. Hence, we hypothesize:

H4a: Hope will be positively associated with support for and willingness to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience in defense of the climate.

Anger is a negative emotion triggered in response to a person feeling that someone or something has done wrong or committed an injustice88, leading to a tendency to retaliate against that which makes people angry104,105. Anger is an action-oriented emotion, and research suggests that it can be a powerful driving force for solidarity in social movements106,107. Several studies have found that feeling angry about global warming is a strong predictor of an individual’s willingness to engage in climate mitigation action and social movements90,92,108,109,110,111,112. Hence, we hypothesize:

H4b: Anger will be positively associated with support for and willingness to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience in defense of the climate.

Prior studies have found that worry about global warming is strongly associated with climate policy support and personal mitigation behaviors18,70,113. Similarly, previous studies have found that worry predicts participation in global warming movements, such as, climate strikes, climate activism, and marches16,114,115. Overall, prior studies indicate that worry about climate change can motivate participation in global warming-related social movements. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H4c: Worry about global warming will be positively associated with support for and willingness to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience in defense of the climate.

According to the theory of normative social behavior, descriptive norms influence people’s behavior116. Descriptive norms are an individual’s perception of whether others behave in a particular way (i.e., how common the behavior is)117. Prior studies indicate that perceptions of what other people are doing to reduce global warming, such as climate activism, collective action, and climate adaptation behaviors, influence people’s opinions about global warming118,119,120,121,122. Thus, we hypothesize:

H5: Descriptive norms will be positively associated with support for and willingness to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience in defense of the climate.

Supporting and identifying with activists influences public engagement in social movements123,124. Social categorization theory (an element of social identity theory) suggests that individuals who strongly identify with a group are more likely to adopt the group’s norms, values, and attitudes as their own and to act in ways that advance the group’s goals and interests125. Therefore, people who support and identify with activists are more likely to willingly support and engage in NVCD, due to a shared identity.

Previous research has found that people (particularly young people) who identified with climate activists (e.g., Greta Thunberg) were more likely to engage in climate strikes126,127. Similarly, Rainsford and Saunders128 found that young people are likely to participate in climate strikes due to their sense of identification with fellow young climate strikers. Further, support for and identification with the climate activism group Extinction Rebellion was strongly related to participating in the environmental movement84. Identifying oneself as an environmental activist is also associated with environmental activism129,130. The relationship between identification with activists and social movement participation provides a sense of empowerment beyond the individual self123,131, which encourages action69. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H6: Identification with climate activists will be positively associated with support for and willingness to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience against corporate or government activities that make global warming worse.

Results

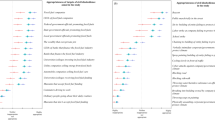

The analyses presented in this study used unweighted data. Previous research has indicated that unweighted regression models tend to exhibit superior effectiveness compared to weighted models in the analysis of data obtained through respondent-driven sampling132. Additional research indicates that preliminary exploratory studies, commonly conducted in respondent-driven sampling, should be carried out without the use of weights to enhance statistical power133. Table 1 presents the regression results for all participants, including standard errors. The hypothesized predictors of support for and willingness to engage in NVCD supported in the final model were: exposure to liberal news (H2a), collective efficacy (H3d), anger (H4b), descriptive norms (H5), and identification with climate activists (H6); all were positively associated with support for and willingness to engage in NVCD. Demographic results showed that respondents who were, respectively, younger, less educated, and Black or Hispanic were more willing to support and engage in NVCD than those who were older, more educated, or White.

Conversely, Democratic party identification (H1), exposure to conservative news (H2b), mainstream news exposure (H2c), global warming belief certainty (H3a), belief that global warming is human-caused (H3b), perceived risk (H3c), hope (H4a), and worry (H4c) were not associated with support for and willingness to engage in NVCD (see Table 1).

We inferred significance from the 95% BCa CI; all variables were significant except gender, education, income, and mainstream news sources—which also explained the least amount of variance in willingness to support and engage in nonviolent civil disobedience (see Table 2). Identification with climate activists explained the most amount of variance in willingness to support and engage in NVCD (10.41%), followed by collective efficacy (5.33%), and anger (4.13%). On the whole, eight variables each explained at least 5% of the variance, together totaling 78.9% (rescaled weight) of the variance in the model.

Discussion

This study sought to identify predictors of support for and willingness to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience against corporate or government activities that make global warming worse. Several but not all hypothesized predictors were confirmed.

Identifying with climate activists was the strongest positive predictor of support for and willingness to engage in NVCD and explained the most amount of variance. This is in line with previous climate-related research which showed that people who identified with climate activists or activism groups such as Greta Thunberg and Extinction Rebellion were more likely to engage in climate strikes84,126,127,128,129,130. Similarly, identifying with activists or opinion-based groups is a stronger predictor of participation in collective action123,131,134. Previous work suggests that certain forms of NVCD, such as physical assault, soup throwing, and breaking into buildings, are considered inappropriate by most Americans135 and may negatively impact identification with climate activists, which in turn could reduce willingness to support and engage in NVCD. Conversely, other forms of NVCD are considered appropriate by a majority of Americans, which when witnessed may increase willingness to support NVCD. The actions of civil disobedience groups, particularly those advocating for climate activism, should be cognizant of the broader social context and assess whether the way they engage in NVCD is likely to move public beliefs, attitudes, policy support, and behavior in a direction aligned with their vision of a just world—or generate alienation or backlash135. Future research should identify what strategies can increase identification with climate activists, and conversely, what factors cause people to dissociate with climate activists136.

We also found that collective efficacy was a strong positive predictor of support for and willingness to engage in NVCD. Previous studies found that collective efficacy is positively related to climate protest participation, political behavior, climate change mitigation intention, climate-related water conservation, climate policy, and pro-environmental behavior16,69,84,86,87,137. This aligns with broader social movement research finding that collective efficacy predicts engagement in collective action138,139,140. Our findings suggest that increasing people’s collective efficacy beliefs may enhance their political engagement and support for nonviolent civil disobedience. When individuals believe in their collective power to effect change, they are more likely to participate in actions that challenge the status quo and demand policy changes6.

Anger was also a significant positive predictor in our study, which is consistent with findings in previous research that anger predicts taking action to reduce global warming92,108,110. Similarly, anger about injustices is a predictor of participation in collective action139,141,142. More generally, experiences of injustice can result in anger which can galvanize people into action143. Our findings highlight that while our measure of anger did not specify a target, the presence of anger itself is correlated with political engagement. This indicates that increasing public engagement on climate change involves more than just informing people about climate science. Cultivating political action requires attention to other psychological determinants such as anger and collective efficacy, which are essential for fostering sustained political engagement139.

We also found that descriptive norms were related to support for and willingness to engage in NVCD. Prior studies indicate that perceptions of what other people are doing to reduce global warming—such as climate activism, collective action, and climate adaptation behaviors—influence people’s opinions about global warming118,119,120,121,122. More generally, descriptive norms have been found to be a predictor of voting intentions and political participation144,145. Here we found that people are more likely to support and participate in NVCD when they perceive that others around them also engage in or approve of such actions.

Furthermore, we found that exposure to the liberal news source MSNBC was positively associated with support for and willingness to engage in NVCD. MSNBC coverage is overtly critical of climate denialism and obstruction64, and therefore consuming this news source may tend to enhance viewers’ support for NVCD. Specifically, our finding emphasizes the need to account for media influences when analyzing public participation in NVCD or other social movements.

Although age was used as a covariate, and we did not hypothesize a relationship between age and NVCD support, younger people were more willing to support and engage in NVCD than older people. This aligns with prior work that finds that younger adults were more willing to support government action to reduce emissions and participate in a climate march66,128,146. Generally, younger people are more willing to engage in collective action147,148,149,150. Younger people are more likely to be angry about climate change, in part because they will experience more of the impacts of climate change128.

Similarly, we found that, in the United States, Black and Hispanic people were more willing to support and engage in NVCD. This aligns with previous research showing that Non-Whites (i.e., Latinos) are more likely to support climate mitigation efforts and to have contacted a government representative to act on climate change45,151. Black and Hispanic Americans are more likely to live in inner cities with air pollution and heat-island effects, which can worsen climate impacts. These findings suggest that non-whites (e.g., Black and Hispanic) may be more willing to engage in climate activism because they perceive climate change as a greater risk45.

Prior research has found that people with higher levels of education are more likely to participate in conventional protests152,153. However, in the context of climate-related NVCD, we found that those with less education were more willing to support and participate in NVCD. Less educated people may be more supportive and engaged in NVCD for a variety of reasons including urgency and threat related to climate change and the influence of social norms. Hence, less education may also lead to a stronger reliance on experiential reasoning, which can be associated with green activism. However, more research is needed to understand the relationship between educational level and support for climate-related NVCD.

Several predictor variables were not significant: political party identification, mainstream and conservative media exposure, belief certainty, human causation, risk perception, hope, and worry. We offer some discussion below into some potential reasons for this.

Prior research has indicated that party identification does not necessarily predict the selection of global warming as the most important voting issue58. While other research identified political party identification as a significant predictor of willingness to join a campaign154, willingness to support or engage in NVCD actions may be more complex, warranting further study. Prior research found that U.S. Democrats and Independents may be influenced to participate by witnessing NVCD, although there was no effect for Republicans11.

Exposure to mainstream and conservative news media were also nonsignificant predictors in the models. This could indicate that coverage of NVCD in conservative media does not predict partisan support or intentions to engage in NVCD, or that levels of popular support for NVCD among conservatives are sufficiently low that additional negative coverage in conservative media does not further decrease levels of support. Regarding mainstream media, prior research found that exposure to mainstream news acts as a proxy for low political interest58, and people with low political interest are less likely to support or engage in political activities such as NVCD.

Key beliefs like belief certainty, human causation, and perceived risk were also not related to support for and willingness to engage in NVCD. These findings are perplexing. It may be that belief certainty and human causation—two closely connected constructs that a large number of Americans accept as true155—may be necessary but not sufficient to affect decisions about NVCD. The Social Identity Model of Collective Action (SIMCA) posits that identity, efficacy beliefs, and a sense of injustice are core predictors of collective action139,156. Our model appears to provide support for the identity and efficacy dimensions of this model. Regarding risk perceptions, our RWA model suggests that despite being nonsignificant in the regression analysis, they do provide additional explanatory variance. For this reason, further investigations into the role of risk perceptions in climate NVCD participation would be useful. Similarly, for emotions, SIMCA would predict anger to be a significant predictor (which was supported) but hope and worry were not significant predictors. However, like risk perceptions, worry explained more variance in the RWA model. These cases suggest that the factors associated with support for or willingness to engage in NVCD are complex. Therefore, RWA could help researchers focus on the predictors that explain more variance.

We found that hope was not a significant predictor of support for and willingness to engage in climate NVCD. Prior works found that having a sense of hope regarding global warming significantly predicts individuals’ support for policy and participation in climate-related activism and social movements97,98,99,100,101,102,103,157. However, the results of this study suggest that other factors, such as anger or collective efficacy, may be more critical in predicting NVCD. One possible explanation for this finding is that while hope may inspire a general sense of optimism and belief in the possibility of change, it may not translate directly into a willingness to take confrontational actions, such as a willingness to engage in NVCD. Instead, feeling angry because of injustice and a belief in a group’s ability to make a difference (collective efficacy) may be more important drivers of climate NVCD. Our study highlights the need for a more detailed understanding of how different emotional and cognitive factors interact to influence individuals’ decisions to support or engage in NVCD.

This study explored multiple potential predictors of support for and willingness to engage in climate NVCD by analyzing theoretically relevant variables such as collective efficacy, anger, perceived risk, political identification, media exposure, and key beliefs about climate change. Our findings offer valuable insights for social science theorists refining models of protest behavior and for climate activists seeking to mobilize broader public involvement in NVCD. Our research extends existing theories by integrating these key predictors and offers practical strategies for enhancing engagement in climate related NVCD.

This study was exploratory; we included a wide range of possible predictors. Hence, future studies could build on this work to construct more precise models based on these findings. Second, the correlational nature of our analysis cannot establish causality of the relationships; experimental studies will be needed to further examine these relationships with the aim of assessing causality. Third, although our findings are relevant to the climate movement, they may not generalize to other social movements, for example, movements to promote racial justice or gender equality. Fourth, future studies should consider using longitudinal or experimental data to better understand if participants already support or have participated in nonviolent civil disobedience (or protest) more generally and the causal relationships between NVCD for climate and other social issues. This will help improve our understanding of the dynamics between past and current support for and willingness to engage in NVCD, identification with climate activists, and other related factors. Finally, while our low variance inflation factor (VIF) suggests multicollinearity was not a serious concern, there may be meaningful correlations between several variables. This calls for future research to delve deeper into the temporal ordering of related constructs, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of their interplay.

To limit global warming, governments and organizations need to take strong and coordinated action to decarbonize the global economy, reduce concentrations of heat-trapping gasses in the atmosphere to pre-industrial levels, and help communities become more resilient to rapidly intensifying climate impacts. Nonviolent civil disobedience is a growing response to government and corporate inaction. In this study, we identify several key predictors of public support for and willingness to engage in NVCD in defense of the climate. Understanding these predictors may be helpful to social science theorists and climate activists seeking to encourage more people to support and participate in NVCD actions.

Methods

The study was approved by George Mason University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB number: 531283). We conducted a nationally representative survey of the U.S. public (n = 1303) from November 8–20, 2019. The sample was drawn from the Ipsos Knowledge Panel, a probability sampling-based online panel, in which people who do not have internet access are given a computer and internet access to participate. Respondents provided their informed consent to participate in the research, and on average, it took about 25 min to complete the full survey. Ipsos Knowledge Panel provided variables for age, race, gender, education, and income information, all of which were utilized as controls in the models described below. Descriptive statistics for age, gender, race, education, and income are shown in Table 3. Gender was recoded such that 0 = male and 1 = female; 50.6% of participants were male, and 49.4% were female. All percentages are unweighted.

Measures

Party identification: party identification was assessed using responses to two questions. First, participants were asked, “Generally speaking, do you think of yourself as a…” with response options of 1 = Republican, 2 = Democrat, 3 = Independent, 4 = Other (Please specify), and 5 = No party/not interested in politics. Participants who selected Independent or Other were asked a follow-up question, “Do you think of yourself as closer to the…” with responses of 1 = Republican Party, 2 = Democratic Party, and 3 = Neither. These two items were combined to create a 5-point nominal scale (1 = Republican, 2 = lean Republican, 3 = Independent/Other, 4 = lean Democrat, 5 = Democrat). If 3 = Neither was chosen in the follow-up question, the response was coded 3 = Independent/Other category on the combined scale. Similarly, if 1 = Republican Party or 2 = Democratic Party were selected in the follow-up question, the responses represented the 2 = lean Republican and 4 = lean Democrat categories of the combined scale. Respondents who chose 5 = No party/not interested in politics to the original question were treated as missing.

Exposure to liberal news sources: MSNBC has a politically liberal point of view 158,159, including on the issue of global warming64. Participants were asked, “How often do you watch, listen to, or read content from the following? MSNBC,” with responses ranging from 1 = Never to 7 = Many times a day (M = 1.84, SD = 1.48).

Exposure to conservative news sources: Fox News has a politically conservative point of view64,160. Participants were asked, “How often do you watch, listen to, or read content from the following? The Fox News Channel,” with responses ranging from 1 = Never to 7 = Many times a day (M = 2.37, SD = 1.87).

Exposure to mainstream news sources: CBS, ABC, and NBC were classified as mainstream news media161. Participants were asked, “How often do you watch, listen to, or read content from the following? The national nightly network news on CBS, ABC, or NBC,” with response options ranging from 1 = Never to 7 = Many times a day (M = 2.89, SD = 1.87).

Belief certainty: to measure certainty about whether global warming is happening or not, participants were presented with a brief definition of global warming and first asked, “Do you think that global warming is happening?” (1 = No, 2 = Don’t know, 3 = Yes) and then, depending on whether they responded “yes” or “no” they were asked, “How sure are you that global warming is [not] happening?” (1 = Not at all sure, 4 = Extremely sure). Responses to these questions were combined to create a nine-point certainty scale (1 = Extremely sure global warming is not happening, 5 = Don’t know, 9 = Extremely sure global warming is happening) (M = 6.90 , SD = 2.82 ).

Human causation: respondents were asked a single question to assess their beliefs about whether global warming is caused by humans—“Assuming global warming is happening, do you think it is …” with responses ranging 1 = Caused mostly by human activities, 2 = Caused mostly by natural changes in the environment, 3 = Caused by natural changes and human activities, 4 = None of the above because global warming is not happening, and 5 = Other (please specify). We dichotomized the measure, such that those who selected “caused mostly by human activities” were coded as 1 and all other responses were coded as 0.

Perceived risk: respondents completed an 8-item measure which assessed how much they believe global warming will harm them personally, their families, people in their community, people in the United States, people in developing countries, the world’s poor, future generations of people, and plant and animal species. The response options were 0 = Don’t know, 1 = Not at all, 2 = Only a little, 3 = A moderate amount, and 4 = A great deal. “Don’t know” responses were treated as missing. The available items were averaged to create an overall risk perception score (α = 0.97, M = 2.89, SD = 0.98).

Collective efficacy: participants completed a 5-item measure about their confidence that people like them, working together, can affect what the following do about global warming: the federal government; their state government; their local government; corporations; and local businesses. The response options were 1 = Not at all confident, 2 = Only a little confident, 3 = Moderately confident, 4 = Very confident, 5 = Extremely confident. The items were averaged to create an overall score of collective efficacy (α = 0.94, M = 2.30, SD = 0.91).

Hope & Anger: to measure hope, participants responded to the statement about the extent to which they feel hopeful when they think about the issue of global warming. To assess anger, participants responded to a statement that asked the extent to which they feel angry when they think about the issue of global warming. The response options for both emotions were 1 = Not at all, 2 = Not very, 3 = Moderately, and 4 = Very (Hope, M = 2.28, SD = 0.90; Anger, M = 2.15; SD = 0.91).

Worry: participants were asked, “How worried are you about global warming?” on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 = Not at all worried to 4 = Very worried (M = 2.79, SD = 1.03).

Descriptive norms: to measure descriptive norms, respondents were asked, “In your estimation, over the past 12 months what percentage of adults (18+ years and older) in the United States contacted elected officials to urge them to take action to reduce global warming?” Participants positioned the slider bar to indicate the value that best describes their response. This ranged from 0% (None) to 100% (All) (M = 26.82, SD = 20.14).

Identification with climate activists: respondents were asked two questions to measure their level of identification with climate activists. First, they were asked, “How much do you support or oppose climate activists who urge elected officials to take action to reduce global warming?” Response options ranged on a five-point scale from 1 = strongly support to 5 = strongly oppose (M = 3.52, SD = 1.33). Second, participants responded to a one-item measure about how much they identify with climate activists. The response options ranged from 1 = Not at all to 4 = A great deal (M = 2.12, SD = 1.11). The responses to the first and second questions were standardized. Afterwards, responses to the two questions were then averaged into an overall score for identification with activists (r = 0.78, p < 0.001, M = 0.0, SD = 0.93).

Support for and willingness to engage in NVCD: our dependent measure was assessed with two items. “How likely would you be to do each of the following things if a person you like and respect asked you to?” (a) Support an organization engaging in nonviolent civil disobedience (e.g., sit-ins, blockades, or trespassing) against corporate or government activities that make global warming worse” and (b) “Personally engage in nonviolent civil disobedience (e.g., sit-ins, blockades, or trespassing) against corporate or government activities that make global warming worse.” Responses to these questions were recoded to 1 = Definitely would not, 2 = Probably would not, 2.5 = Don’t know, 3 = Probably would, to 4 = Definitely would, 99 = Prefer not to answer (which was treated as missing data). Those who indicated “Don’t know” were treated as midpoint, while “Prefer not to answer” were treated as missing. Because these two measures were highly correlated (r = 0.79, p < 0.001), we combined them into a single variable for parsimony in the models (M = 1.90; SD = 0.91). To demonstrate consistency in the results, we have included the regression results for each dependent variable individually in the supplementary material (Tables S5 and S6).

We conducted a supplementary analysis to examine whether the measure we utilized for nonviolent civil disobedience (NVCD) had a different pattern of responses than for “willingness to attend a rally” (a lower-risk form of activism). The regression analysis results are provided in Table S7 for the “willingness to attend a rally” variable (Supplementary Material) and Table 1 for the NVCD variable (the dependent variable in our paper).

We found some similarities and differences in the relationships between predictor variables and these two outcomes. We found that four predictors (exposure to liberal news sources, collective efficacy, anger, and identification with climate activists) were positively associated with willingness to attend a rally. Similarly, exposure to liberal news sources, collective efficacy, anger, and identification with climate activists predicted willingness to engage in NVCD. For the differences, while we found that no demographic variables were significantly associated with willingness to attend a rally; a broader range of factors, including other demographic variables and descriptive norms, predicted willingness to engage in NVCD. For example, age and education were negatively related to support for and willingness to engage in NVCD. Additionally, race (Black and Hispanic Americans) and descriptive norms were positively related to support for and willingness to engage in NVCD.

Also, we conducted supplementary analysis of descriptives for “willingness to attend a rally” and “willingness to engage in NVCD” (supplementary material, Tables S8 and S9). We found that willingness to attend a rally is higher than willingness to engage in NVCD, thus suggesting that NVCD may be perceived as higher risk. There was a significant difference in the scores for “willingness to support for and engage in NVCD” (M = 1.90, SD = 0.91) and “willingness to attend a rally” (M = 2.12, SD = 0.96), t (1302) = −10.90, p < 0.001. This supports the argument that there are meaningful differences between these two measures, suggesting that participants may be responding differently to low-risk climate protest behaviors like attending a rally compared to potential NVCD activities.

These differences in predictors for the two types of collective action support the idea that respondents perceive and respond to these questions differently. Although we do not have questions that directly assess whether participants perceive these various actions to be illegal, this supplementary analysis begins to address the concern that the NVCD question is interpreted similarly to other lower-risk forms of protest action.

Regression analysis was used to test our hypotheses by examining the relationships between the predictors and support for and willingness to engage in NVCD. The predictors included demographic variables (age, gender, race, education, and income), party identification, mainstream news sources, conservative news sources, liberal news sources, belief certainty, human causation, risk perception, collective efficacy, worry, hope, anger, descriptive norms, and identification with climate activists.

Since regression coefficients are sensitive to other variables in the model, they frequently do not provide accurate estimates of effect size; thus, regression analysis does not necessarily elucidate the relative importance of each predictor162,163. Consequently, after conducting the regression analysis, we used a web-based relative weight analysis (RWA) tool developed by Mizumoto164 (based on prior work165) to estimate the amount of variance each predictor explains in the linear model, as well as generate significance tests for the raw weights of each predictor (based on 10,000 replications bootstrapping approach at the 95% confidence interval. Additionally, we used bias corrected and accelerated (BCa) confidence intervals (CIs) to determine which of the variables in the RWA were statistically significant. BCa CIs works by comparing the variables in RWA to a randomly generated variable with a population relative weight of zero166. Statistical significance for each RWA variable is then identified by looking at whether the BCa CI crosses zero. If not, then the variable in the RAW explains a statistically significant amount of variance at the p < 0.05 level166.

RWA produces two primary effect size metrics, raw weights and rescaled weights. The total model R2 is the sum of the raw weights, representing the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that each variable explains. Rescaled weights show how much of the variance is explained by each predictor relative to how much is explained by the entire model (i.e., rescaled weights sum to 100%).

To replace missing data, we used Hotdeck imputation (Myers167) with age, gender, and education as the deck variables (see Table S1 in the Supplementary Material for original % missing). Hence the sample size for the analysis was the full sample (n = 1303). Further, we assessed multicollinearity by examining Variation Inflation Factor (VIF) and tolerance scores variables in all the models. All VIF scores were below 4.32, and all tolerance scores were above 0.22, indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern (Kleinbaum et al.168; see details in Supplementary Material Table S2).

Data availability

The authors will provide the data supporting the findings of the study upon reasonable request.

Change history

17 July 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44168-025-00277-8

References

IPCC. Summary for policymakers. in Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Core Writing Team, Lee, H. & Romero, J.) 1–34 (IPCC, 2023).

EPA. Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions. EPA. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions (2022).

Kinyon, L., Dolšak, N. & Prakash, A. When, where, and which climate activists have vandalized museums. npj Clim. Action 2, 27 (2023).

Watts, J. Germany’s dirty coalmines become the focus for a new wave of direct action. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/nov/08/germanys-dirty-coalmines-become-the-focus-for-a-new-wave-of-direct-action (2017).

Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice (Harvard University Press, 1999).

Chenoweth, E. Civil Resistance: What Everyone Needs to Know? (Oxford University Press, 2021).

Schank, E. Scientists arrested for peaceful climate protests around the World Say “Climate Revolution Now”. Salon. https://www.salon.com/2022/04/08/scientists-arrested-for-peaceful-climate-around-the-world-say-climate-revolution-now/ (2022).

Lemons, J. & Brown, D. A. Global climate change and nonviolent civil disobedience. Ethics Sci. Environ. Polit. 11, 3–12 (2011).

Campbell, E., Kotcher, J., Maibach, E., Rosenthal, S., & Leiserowitz, A. Climate Change and Civil Disobedience. Yale University and George Mason University (Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, 2022).

Leiserowitz, A., Roser-Renouf, C., Marlon, J. & Maibach, E. Global Warming’s Six Americas: a review and recommendations for climate change communication. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 42, 97–103 (2021).

Bugden, D. Does climate protest work? Partisanship, protest, and sentiment pools. Socius, 6, 1-13 (2020).

Doran, R., Ogunbode, C. A., Böhm, G. & Gregersen, T. Exposure to and learning from the IPCC special report on 1.5 °C global warming, and public support for climate protests and mitigation policies. npj Clim. Action 2, 11 (2023).

Lee, F. L. F. Social movement as civic education: communication activities and understanding of civil disobedience in the Umbrella Movement. Chin. J. Commun. 8, 393–411 (2015).

Behr, D., Braun, M., Kaczmirek, L. & Bandilla, W. Item comparability in cross-national surveys: results from asking probing questions in cross-national web surveys about attitudes towards civil disobedience. Qual. Quant. 48, 127–148 (2012).

Haugestad, C. A. P., Skauge, A. D., Kunst, J. R. & Power, S. A. Why do youth participate in climate activism? A mixed-methods investigation of the #FridaysForFuture climate protests. J. Environ. Psychol. 76, 101647 (2021).

Roser-Renouf, C., Maibach, E. W., Leiserowitz, A. & Zhao, X. The genesis of climate change activism: from key beliefs to political action. Clim. Change 125, 163–178 (2014).

Van der Linden, S. L., Leiserowitz, A. A., Feinberg, G. D. & Maibach, E. W. The scientific consensus on climate change as a gateway belief: experimental evidence. PLoS ONE 10, 1–8 (2015).

Van der Linden, S., Leiserowitz, A. & Maibach, E. The gateway belief model: a large-scale replication. J. Environ. Psychol. 62, 49–58 (2019).

Wright, S. C. Collective action and social change. In Dovidio J. F., Hewstone M., Glick P., Esses V. M. (Eds.), Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination, (SAGE, 2010).

Becker, J. C. & Tausch, N. A. dynamic model of engagement in normative and non-normative collective action: psychological antecedents, consequences, and barriers. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 26, 43–92 (2015).

Celikates, R. Rethinking civil disobedience as a practice of contestation-beyond the liberal paradigm. Constell 23, 37–45 (2016).

Danielsen, S. Mobilizing on abortion: social networks, civil disobedience, and the clergy consultation service on abortion, 1967–1973. J. Church State 63, 461–484 (2021).

Llewellyn, J. J. Transforming restorative justice. Int. J. Restor. Just. 4, 374 (2021).

Scheuerman, W. E. Political disobedience and the climate emergency. Philos. Soc. Crit. 48, 791–812 (2021).

Trumpy, A. J. Woman vs. fetus: frame transformation and intramovement dynamics in the pro-life movement. Sociol. Spectr. 34, 163–184 (2014).

Wilt, M. P. Civil disobedience and the rule of law: punishing good lawbreaking in a new era of protest. Geo. Mason. UCRLJ 28, 43 (2017).

Martiskainen, M. et al. Contextualizing climate justice activism: knowledge, emotions, motivations, and actions among climate strikers in six cities. Glob. Environ. Change 65, 102180 (2020).

Beck, U., Blok, A., Tyfield, D. & Zhang, J. Y. Cosmopolitan communities of climate risk: conceptual and empirical suggestions for a new research agenda. Glob. Netw. J. 13, 1–21 (2013).

Boykoff, M. T. & Boykoff, J. M. Climate change and journalistic norms: a case-study of US mass-media coverage. Geoforum 38, 1190–1204 (2007).

Nisbet, M. C. & Myers, T. The polls—trends twenty years of public opinion about global warming. Public Opin. Q. 71, 444–470 (2007).

United Nations News. Ban urges leaders at Davos to forge “green new deal” to fight world recession | UN News. United Nations. https://news.un.org/en/story/2009/01/289302 (2009).

McCoy, D., Montgomery, H., Arulkumaran, S. & Godlee, F. Climate change and human survival. BMJ 348, g2351 (2014).

Patz, J., Gibbs, H., Foley, J., Rogers, J. & Smith, K. Climate change and global health: quantifying a growing ethical crisis. EcoHealth 4, 397–405 (2007).

Bennett, H. et al. Health and equity impacts of climate change in Aotearoa–New Zealand, and health gains from climate action. N. Z. Med. J. 127, 16–31 (2014).

Haines, A. et al. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: overview and implications for policy makers. Lancet 374, 2104–2114 (2009).

Jones, R., Bennett, H., Keating, G. & Blaiklock, A. Climate change and the right to health for Māori in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Health Hum. Rights16, 54–68 (2014).

Tonmoy, F. N., Cooke, S. M., Armstrong, F. & Rissik, D. From science to policy: development of a climate change adaptation plan for the health and wellbeing sector in Queensland, Australia. Environ. Sci. Policy 108, 1–13 (2020).

Watts, N. et al. Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health. Lancet 386, 1861–1914 (2015).

Berglund, O. Disruptive protest, civil disobedience & direct action. Politics 45, 1–19 (2023).

Mason, L. Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity (University of Chicago Press, 2018).

Huddy, L., Mason, L. & Aarøe, L. Expressive partisanship: campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 109, 1–17 (2015).

Achen, C. H. & Bartels, L. M. Democracy for Realists: Why Elections do not Produce Responsive Government (Princeton University Press, 2017).

Iyengar, S. & Westwood, S. J. Fear and loathing across party lines: new evidence on group polarization. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 59, 690–707 (2015).

Greene, S. Social identity theory and party identification*. Soc. Sci. Q. 85, 136–153 (2004).

Ballew, M. T., Goldberg, M. H., Rosenthal, S. A., Cutler, M. J. & Leiserowitz, A. Climate change activism among Latino and White Americans. Front. Commun. 3, 1–15 (2019).

Goldberg, M. H., Gustafson, A., Ballew, M. T., Rosenthal, S. A. & Leiserowitz, A. Identifying the most important predictors of support for climate policy in the United States. Behav. Public Policy 5, 480–502 (2020).

Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A., Bain, P. G. & Fielding, K. S. Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 622–626 (2016).

McCright, A. M., Dunlap, R. E. & Xiao, C. Increasing influence of party identification on perceived scientific agreement and support for government action on climate change in the United States, 2006–12. Weather Clim. Soc. 6, 194–201 (2014).

Ansah, P. O. et al. Predictors of U.S. public support for climate aid to developing countries. Environ. Res. Commun. 5, 125003 (2023).

Brulle, R. J., Carmichael, J. & Jenkins, J. C. Shifting public opinion on climate change: an empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the U.S., 2002–2010. Clim. Change 114, 169–188 (2012).

McCright, A. M. & Dunlap, R. E. The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public’s views of global warming, 2001-2010. Sociol. Q. 52, 155–194 (2011).

Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A. & Fielding, K. S. Relationships among conspiratorial beliefs, conservatism and climate scepticism across nations. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 614–620 (2018).

McCright, A. M. & Dunlap, R. E. The nature and social bases of progressive social movement ideology: examining public opinion toward social movements. TSQ 49, 825–848 (2008).

Bolsen, T. & Shapiro, M. A. The U.S. News Media, polarization on climate change, and pathways to effective communication. Environ. Commun. 12, 149–163 (2018).

Druckman, J. N., Peterson, E. & Slothuus, R. How elite partisan polarization affects public opinion formation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 107, 57–79 (2013).

Kinder, D. R. & Kalmoe, N. P. Neither Liberal Nor Conservative: Ideological Innocence in the American Public (University of Chicago Press, 2017).

McCombs, M. E. & Shaw, D. L. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin. Q. 36, 176 (1972).

Campbell, E., Kotcher, J., Maibach, E., Rosenthal, S. A. & Leiserowitz, A. Predicting the importance of global warming as a voting issue among registered voters in the United States. Curr. Res. Ecol. Soc. Psychol. 2, 100008 (2021).

Wojcieszak, M., Bimber, B., Feldman, L. & Stroud, N. J. Partisan news and political participation: exploring mediated relationships. Pol. Comm. 33, 241–260 (2016).

Martin, G. J. & Yurukoglu, A. Bias in cable news: persuasion and polarization. Am. Econ. Rev. 107, 2565–2599 (2017).

Weaver, D. A. & Scacco, J. M. Revisiting the protest paradigm. Int. J. Press/Polit. 18, 61–84 (2012).

Feldman, L., Maibach, E. W., Roser-Renouf, C. & Leiserowitz, A. Climate on cable. Int. J. Press/Polit. 17, 3–31 (2012).

Krosnick, J. A. & MacInnis, B. Frequent Viewers of Fox News Are Less Likely to Accept Scientists’ Views of Global Warming. Report for The Woods Institute for the Environment. http://woods.stanford.edu/docs/surveys/Global-Warming-Fox-News.pdf (2010).

Feldman, L. Effects of T.V. and cable news viewing on climate change opinion, knowledge, and behavior. In Nisbet M. C. (ed.) Oxford Encyclopedia of Climate Change Communication. New York: Oxford University Press, (2016).

Carmichael, J. T., Brulle, R. J. & Huxster, J. K. The great divide: understanding the role of media and other drivers of the Partisan Divide in public concern over climate change in the USA, 2001–2014. Clim. Change 141, 599–612 (2017).

Krosnick, J. A., Holbrook, A. L., Lowe, L. & Visser, P. S. The origins and consequences of Democratic Citizens’ policy agendas: a study of popular concern about global warming. Clim. Change 77, 7–43 (2006).

Van der Linden, S. The Gateway Belief Model (GBM): a review and research agenda for communicating the scientific consensus on climate change. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 42, 7–12 (2021).

Maartensson, H. & Loi, N. M. Exploring the relationships between risk perception, behavioural willingness, and constructive hope in pro-environmental behaviour. Environ. Educ. Res. 28, 600–613 (2021).

Rees, J. H. & Bamberg, S. Climate protection needs societal change: determinants of intention to participate in collective climate action. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 44(5), 466–473 (2014).

Van der Linden, S. Determinants and measurement of climate change risk perception, worry and concern. In Schafer, M., Markowitz, E., Ho, S., O’Neill, S., Thaker, J., Nisbet, M. C. (Eds.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Climate Change Communication 369–401, (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2017).

Wallis, H. & Loy, L. S. What drives pro-environmental activism of young people? A survey study on the Fridays for Future Movement. J. Environ. Psychol. 74, 101581 (2021).

Vainio, A. & Paloniemi, R. Does belief matter in climate change action?. Public Underst. Sci. 22, 382–395 (2011).

Arbuckle, J. G., Morton, L. W. & Hobbs, J. Farmer beliefs and concerns about climate change and attitudes toward adaptation and mitigation: evidence from Iowa. Clim. Change 118, 551–563 (2013).

Ding, D., Maibach, E. W., Zhao, X., Roser-Renouf, C. & Leiserowitz, A. Support for climate policy and societal action are linked to perceptions about scientific agreement. Nat. Clim. Change 1, 462–466 (2011).

Cook, J. et al. Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 048002 (2016).

Myers, K. F., Doran, P. T., Cook, J., Kotcher, J. E. & Myers, T. A. Consensus revisited: quantifying scientific agreement on climate change and climate expertise among Earth scientists 10 years later. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 104030 (2021).

Tosun, J. & Schoenefeld, J. J. Collective climate action and networked climate governance. WIREs Clim. Change 8, e440 (2017).

Myers, T. A., Maibach, E., Peters, E. & Leiserowitz, A. Simple messages help set the record straight about scientific agreement on human-caused climate change: the results of two experiments. PLoS ONE 10, 1–17 (2015).

Leiserowitz, A. Climate change risk perception and policy preferences: the role of affect, imagery, and values. Clim. Change 77, 45–72 (2006).

Lubell, M., Vedlitz, A., Zahran, S. & Alston, L. T. Collective action, environmental activism, and Air Quality Policy. Polit. Res. Q 59, 149–160 (2006).

Milfont, T. L. The interplay between knowledge, perceived efficacy, and concern about global warming and climate change: a one-year longitudinal study. Risk Anal. 32, 1003–1020 (2012).

Zahran, S., Brody, S. D., Grover, H. & Vedlitz, A. Climate change vulnerability and policy support. Soc. Nat. Resour. 19, 771–789 (2006).

Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy in Changing Societies (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Furlong, C. & Vignoles, V. L. Social Identification in collective climate activism: predicting participation in the environmental movement, Extinction Rebellion. Identity 21, 20–35 (2021).

Hamann, K. R. & Reese, G. My influence on the World (of others): goal efficacy beliefs and efficacy affect predict private, public, and activist Pro-Environmental. Behav. J. Soc. Issues 76, 35–53 (2020).

Thaker, J., Maibach, E., Leiserowitz, A., Zhao, X. & Howe, P. The role of collective efficacy in climate change adaptation in India. Weather Clim. Soc. 8, 21–34 (2016).

Wang, X. The role of attitudinal motivations and collective efficacy on Chinese consumers’ intentions to engage in personal behaviors to mitigate climate change. J. Soc. Psychol. 158, 51–63 (2017).

Lazarus, R. S. Emotion and Adaptation (Oxford University Press, 1991).

Smith, C. A. & Ellsworth, P. C. Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 48, 813–838 (1985).

Nabi, R. L. Discrete emotions and persuasion. In Dillard, J. P., Pfau, M., The Persuasion Handbook: Developments in Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks: 289-308, (SAGE Publications, 2002).

Bieniek-Tobasco, A. et al. Communicating climate change through documentary film: imagery, emotion, and efficacy. Clim. Change 154, 1–18 (2019).

Chu, H. & Yang, J. Z. Emotion and the psychological distance of climate change. Sci. Commun. 41, 761–789 (2019).

Myers, T. A., Roser-Renouf, C. & Maibach, E. Emotional responses to climate change information and their effects on policy support. Front. Clim. 5, 1–12 (2023).

Lazarus, R. S. Emotions and interpersonal relationships: toward a person-centered conceptualization of emotions and coping. J. Pers. 74, 9–46 (2006).

Myers, T. A., Nisbet, M. C., Maibach, E. W. & Leiserowitz, A. A. A public health frame arouses hopeful emotions about climate change. Clim. Change 113, 1105–1112 (2012).

Stern, P. C. Fear and hope in climate messages. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 572–573 (2012).

Courville, S. & Piper, N. Harnessing hope through NGO activism. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 592, 39–61 (2004).

Chadwick, A. E. Toward a theory of persuasive hope: effects of cognitive appraisals, hope appeals, and hope in the context of climate change. Health Commun. 30, 598–611 (2015).

Foster-Fishman, P. G., Cantillon, D., Pierce, S. J. & Van Egeren, L. A. Building an active citizenry: the role of neighborhood problems, readiness, and capacity for change. Am. J. Community Psychol. 39, 91–106 (2007).

Kleres, J. & Wettergren, Å. Fear, hope, anger, and guilt in climate activism. Soc. Mov. Stud. 16, 507–519 (2021).

Markowitz, E. M. & Shariff, A. F. Climate change and moral judgement. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 243–247 (2012).

Ojala, M. Hope and climate change: the importance of hope for environmental engagement among young people. Environ. Educ. Res. 18, 625–642 (2011).

Stevenson, K. & Peterson, N. Motivating action through fostering climate change hope and concern and avoiding despair among adolescents. Sustainability 8, 6 (2015).

Han, S., Lerner, J. S. & Keltner, D. Feelings and consumer decision making: the appraisal-tendency framework. J. Consum. Psychol. 17, 158–168 (2007).

Yang, J. Z. & Chu, H. Who is afraid of the Ebola outbreak? The influence of discrete emotions on risk perception. J. Risk Res. 21, 834–853 (2018).

Carver, C. S. & Harmon-Jones, E. Anger is an approach-related affect: evidence and implications. Psychol. Bull. 135, 183–204 (2009).

Rodgers, K. ‘Anger is why we’re all here’: mobilizing and managing emotions in a professional activist organization. Soc. Mov. Stud. 9, 273–291 (2010).

Lu, H. & Schuldt, J. P. Compassion for climate change victims and support for mitigation policy. J. Environ. Psychol. 45, 192–200 (2016).

McDonald, R. I., Chai, H. Y. & Newell, B. R. Personal experience and the ‘psychological distance’ of climate change: an integrative review. J. Environ. Psychol. 44, 109–118 (2015).

Stanley, S. K., Hogg, T. L., Leviston, Z. & Walker, I. From anger to action: differential impacts of eco-anxiety, eco-depression, and eco-anger on climate action and wellbeing. J. Clim. Change Health 1, 100003 (2021).

Thomas, E. F. et al. Whatever happened to Kony2012? understanding a global internet phenomenon as an emergent social identity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 45, 356–367 (2015).

Wlodarczyk, A., Basabe, N., Páez, D. & Zumeta, L. Hope and anger as mediators between collective action frames and participation in collective mobilization: the case of 15-M. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 5, 200–223 (2017).

Bouman, T. et al. When worry about climate change leads to climate action: how values, worry and personal responsibility relate to various climate actions. Glob. Environ. Change 62, 1–11 (2020).

Brügger, A., Gubler, M., Steentjes, K. & Capstick, S. B. Social Identity and risk perception explain participation in the Swiss youth climate strikes. Sustainability 12, 10605 (2020).

Noth, F. & Tonzer, L. Understanding climate activism: who participates in climate marches such as “Fridays for future” and what can we learn from it?. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 84, 102360 (2022).

Rimal, R. N., Lapinski, M. K., Cook, R. J. & Real, K. Moving toward a theory of normative influences: how perceived benefits and similarity moderate the impact of descriptive norms on behaviors. J. Health Commun. 10, 433–450 (2005).

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R. & Kallgren, C. A. A focus theory of normative conduct: recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 58, 1015–1026 (1990).

Cialdini, R. B. Crafting normative messages to protect the environment. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 12, 105–109 (2003).

Doherty, K. & Webler, T. Social norms and efficacy beliefs drive the alarmed segment’s public-sphere climate actions. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 879–884 (2016).

Gonzalez, A. M., Reynolds-Tylus, T. & Skurka, C. Young adults’ willingness to engage in climate change activism: an application of the theory of normative social behavior. Environ. Commun. 16, 388–407 (2021).

Smith, J. R. et al. Congruent or conflicted? The impact of injunctive and descriptive norms on environmental intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 32, 353–361 (2012).

van Valkengoed, A. M. & Steg, L. Meta-analyses of factors motivating climate change adaptation behaviour. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 158–163 (2019).

Simon, B. et al. Collective identification and social movement participation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 646–658 (1998).

Thomas, E. F., McGarty, C. & Mavor, K. I. Transforming “apathy into movement”: the role of prosocial emotions in motivating action for social change. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 13, 310–333 (2009).

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D. & Wetherell, M. S. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory (Blackwell, 1987).

Sabherwal, A. et al. The Greta Thunberg effect: familiarity with Greta Thunberg predicts intentions to engage in climate activism in the United States. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 51, 321–333 (2021).

Wahlström, M., Kocyba, P., De Vydt, M. & de Moor, J. Protest for a future: composition, mobilization and motives of the participants in Fridays for Future climate protests on 15 march, 2019 in 13 European cities. https://osf.io/xcnzh/ (2019).

Rainsford, E. & Saunders, C. Young climate protesters’ mobilization availability: climate marches and school strikes compared. Front. Polit. Sci. 3, 713340 (2021).

Bamberg, S., Rees, J. & Seebauer, S. Collective climate action: determinants of participation intention in community-based pro-environmental initiatives. J. Environ. Psychol. 43, 155–165 (2015).

Fielding, K. S., McDonald, R. & Louis, W. R. Theory of planned behaviour, identity and intentions to engage in environmental activism. J. Environ. Psychol. 28, 318–326 (2008).

Stürmer, S. & Simon, B. Collective action: towards a dual-pathway model. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 15, 59–99 (2004).

Avery, L. et al. Unweighted regression models perform better than weighted regression techniques for respondent-driven sampling data: results from a simulation study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 19, 1–13 (2019).

Miratrix, L. W., Sekhon, J. S., Theodoridis, A. G. & Campos, L. F. Worth weighting? How to think about and use weights in survey experiments. Polit. Anal. 26, 275–291 (2018).

Thomas, E. F., McGarty, C. & Mavor, K. I. Group interaction as the crucible of social identity formation: a glimpse at the foundations of social identities for collective action. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 19, 137–151 (2015).

Badullovich, N. et al. How does public perception of climate protest influence support for climate action?. npj Clim. Action. 3, 16 (2024).

Stenhouse, N. & Heinrich, R. Breaking negative stereotypes of climate activists: a conjoint experiment. Sci. Commun. 41, 339–368 (2019).

Thaker, J., Howe, P., Leiserowitz, A. & Maibach, E. Perceived collective efficacy and trust in government influence public engagement with climate change-related water conservation policies. Environ. Commun. 13, 681–699 (2019).

Pozzi, M. et al. ‘Coming together to awaken our democracy’: examining precursors of emergent social identity and collective action among activists and non-activists in the 2019–2020 ‘chile despertó’ protests. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 32, 830–845 (2022).

van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T. & Spears, R. Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: a quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychol. Bull. 134, 504–535 (2008).

Velasquez, A. & LaRose, R. Youth collective activism through social media: the role of collective efficacy. N. Media Soc. 17, 899–918 (2015).

Leach, C. W., Iyer, A. & Pedersen, A. Anger and guilt about ingroup advantage explain the willingness for political action. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 32, 1232–1245 (2006).

Walker, I. & Smith, H. J. Relative Deprivation: Specification, Development, and Integration (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Harmon-Jones, E. Anger and the behavioral approach system. Pers. Individ. Dif. 35, 995–1005 (2003).

Sani, G. M. D. & Quaranta, M. Chips off the old blocks? The political participation patterns of parents and children in Italy. Soc. Sci. Res. 50, 264–276 (2015).

Glynn, C. J., Huge, M. E. & Lunney, C. A. The influence of perceived social norms on college students’ intention to vote. Polit. Commun. 26, 48–64 (2009).

McCright, A. M., Dunlap, R. E. & Xiao, C. Perceived scientific agreement and support for government action on climate change in the USA. Clim. Change 119, 511–518 (2013).

Ang, A. U., Dinar, S. & Lucas, R. E. Protests by the young and digitally restless: the means, motives, and opportunities of anti-government demonstrations. Inf. Commun. Soc. 17, 1228–1249 (2014).

Valenzuela, S., Arriagada, A. & Scherman, A. The social media basis of youth protest behavior: the case of Chile. J. Commun. 62, 299–314 (2012).

Valenzuela, S., Arriagada, A. & Scherman, A. Facebook, Twitter, and youth engagement: a quasi-experimental study of social media use and protest behavior using propensity score matching. Int. J. Commun. 8, 25–39 (2014).

Weiner, E. & Federico, C. M. Authoritarianism, institutional confidence, and willingness to engage in collective action. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 43, 392–406 (2017).

Schuldt, J. P. & Pearson, A. R. The role of Race and ethnicity in climate change polarization: evidence from a U.S. national survey experiment. Clim. Change 136, 495–505 (2016).

DiGrazia, J. Individual protest participation in the United States: conventional and unconventional activism. Soc. Sci. Q. 95, 111–31 (2014).

Schussman, A., Sarah, A. & Soule, S. A. Process and protest: accounting for individual protest participation. Soc. Forces 84, 1083–108 (2005).

Munson, S., Kotcher, J., Maibach, E., Rosenthal, S. A. & Leiserowitz, A. The role of felt responsibility in climate change political participation. Oxf. Open Clim. Change 1, 1–8 (2021).

Leiserowitz, A. et al. Climate Change in the American Mind: Politics & Policy, Spring 2023. Yale University and George Mason University (Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, 2023).

Thomas, E. F., Zubielevitch, E., Sibley, C. G. & Osborne, D. Testing the social identity model of collective action longitudinally and across structurally disadvantaged and advantaged groups. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 46, 823–838 (2020).

Solnit, R. Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities. Militarization (Duke University Press, 2020).

Kaye, B. K. & Johnson, T. J. Across the great divide: how partisanship and perceptions of media bias influence changes in time spent with media. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 60, 604–623 (2016).

Padgett, J., Dunaway, J. L. & Darr, J. P. As seen on T.V.? How gatekeeping makes the U.S. House seem more extreme. J. Commun. 69, 696–719 (2019).

Feldman, L., Myers, T. A., Hmielowski, J. D. & Leiserowitz, A. The mutual reinforcement of media selectivity and effects: testing the reinforcing spirals framework in the context of global warming. J. Commun. 64, 590–611 (2014).

Boykoff, M. T. Lost in translation? United States television news coverage of Anthropogenic climate change, 1995–2004. Clim. Change 86, 1–11 (2008).

Lebreton, J. M., Ployhart, R. E. & Ladd, R. T. A Monte Carlo comparison of relative importance methodologies. Organ. Res. Methods 7, 258–282 (2004).

Tonidandel, S. & LeBreton, J. M. Relative importance analyses: a useful supplement to multiple regression analyses. J. Bus. Psychol. 26, 1–9 (2011).

Mizumoto, A. Langtest (Version 1.0) [Web application]. http://langtest.jp (2015).

Tonidandel, S. & LeBreton, J. M. RWA web: a free, comprehensive, web-based, and user-friendly tool for relative weight analyses. J. Bus. Psychol. 30, 207–216 (2015).

Tonidandel, S., LeBreton, J. M. & Johnson, J. W. Determining the statistical significance of relative weights. Psychol. Methods 14, 387–399 (2009).

Myers, T. A. Goodbye, Listwise Deletion: Presenting Hot Deck Imputation as an Easy and Effective Tool for Handling Missing Data. Commun Methods Meas 5, 297–310 (2011).

Kleinbaum, D. G., Kupper, L. L., Nizam, A. & Rosenberg, E. S. Applied regression analysis and other multivariable methods. Cengage Learn (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, which have significantly improved this manuscript. Funding for this project is provided by the 11th Hour Project, the Energy Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, and the Grantham Foundation. For information on Climate Change in the American Mind (CCAM), please refer to the following link: https://www.climatechangecommunication.org/climate-change%20in-the-american-mind/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions