Abstract

Early nautiloids evolved siphon-like structures hundreds of millions of years ago as a propulsion mechanism for maneuvering in underwater environments. Over time, siphons became the cephalopod method for jetting locomotion, but few bio-mimetic soft robotic replicas have been developed. The principal challenge is the limited selection of solid-state, active soft materials that can replicate the function of the active mantle in a natural siphon. Here, we present a Nautilus-inspired propulsion system that employs multilayered solid-state dielectric elastomer actuators (DEAs) to produce an artificial siphon. The system features a soft robotic siphon, onboard sensors for semi-autnonomous operation, and a 3D-printed shell with an internal air pocket for buoyancy and self-righting ability. Through analytical modeling and empirical approaches, we develop a soft muscle for vortex ring formation and thrust output of 17 mN at 2 kV. These findings provide a framework for designing soft actuators that can be used as new propulsors to enable efficient (Cost of Transport = 2.51), low-noise, underwater locomotion for exploration and environmental monitoring applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cephalopods are the only natural swimmers to use jet propulsion as a method for underwater locomotion, which can be highly energy efficient at low speeds1. This jetting capability arises from a primary anatomical features: a soft, hollow mantle cavity that expands and contracts to draw in and expel water2,3. Unlike most fish or marine mammals that rely on undulatory motions of rigid skeletal systems, cephalopods leverage the added-mass effects, fluid volume changes, and vortex ring formation to propel themselves efficiently through the water4,5. These natural mechanics of cephalopod jet propulsion provide a compelling blueprint for bioinspired engineering solutions, offering advantages in maneuverability, reduced noise generation, and mechanical simplicity.

Despite its simplicity, a siphon is challenging to reproduce in soft robotic systems, which use bioinspiration as design guidance6,7,8. The primary challenge is the limited selection of solid state, artificial muscles that can be used as the active material in an artificial mantle. A rigid motor demonstration proved that reproducing the volume change of a mantle leads to jetting propulsion9. Cable-driven mantles can be made completely from soft materials, yet still require rigid motors10. Hydraulic systems can generate substantial pressure and flow regulation for thrust vectoring, but tend to be large, power intensive, and difficult to fully seal for standalone operation11. To reproduce biomimetic siphons, the primary requirements for soft actuators are that they (i) can provide sufficient energy density while deforming as soft membranes out of plane relative to a mechanical ground, (ii) are made completely from solid-state materials for operation across broad depths in aquatic environments, and (iii) allow for operation at power levels accessible by commercial high voltage boosters and peripherals.

Dielectric elastomer actuators (DEAs) have the necessary attributes to address these requirements, as electro-mechanical transducers that convert electrical energy into mechanical work12. Despite the advantage of a simple construction, most DEAs are limited by the need for a rigid frame, which keeps the elastomer in a strained state for improved electro-mechanical performance, but makes the entire assembly rigid13. As a result, most underwater robots powered by DEAs leverage deformable frames to produce undulatory locomotion14. An alternative approach uses frameless fluid electrodes and the surrounding water as electrical ground15. One demonstration has shown the ability to eject water from a cavity using a DEA membrane expanding out of plane, but it required an additional rigid pump to pressurize the membrane16. Advances in multilayering17and material selection18 have produced DEAs which are soft and lightweight, while demonstrating either high energy density (20 kJ/kg) or rapid response (up to 200 Hz)19. Multilayered DEAs can be adapted to address all of the siphon requirements, including power autonomy, as previously demonstrated in robots with flapping fins20.

In this work, we introduce a novel underwater propulsion system that leverages multilayer, solid-state DEAs to replicate the shape-changing siphon mechanism of the Nautilus. While previous studies have demonstrated the feasibility of DEAs in soft robotic components, no existing systems achieve true cephalopod-like jet propulsion without the assistance of a rigid device (spring, pump, motor, etc.) or by relying on undulatory fin like motion. Our design achieves pulsed-jets by using a soft actuator to directly impart energy into the working fluid. We further characterize the mechanical and electrical performance of the actuator and flow characteristics of the siphon to assess contributions to thrust generation. Finally, we show that the resulting system can achieve autonomous operation with onboard vision, temperature, and salinity sensing, moving at speeds up to 40 cm/min (2.5 BL/min) in a self-contained platform.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In the section “Results”, we present the design, experimental thrust measurements, and flow characteristics for our bioinspired Nautilus system. Section “Methods” details the materials, fabrication steps, and dynamic mechanical analyses of the DEAs, while section “Discussion” discusses the implications of our findings for future underwater soft robotics and highlights potential improvements.

Results

Design of bioinspired Nautilus system

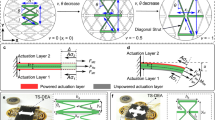

We developed a 3D-printed Nautilus-inspired robot that integrates a flexible siphon and onboard sensors to emulate cephalopod-like jet propulsion (Fig. 1C). The shell geometry is based on the Nautilus belauensis, with selected internal walls removed to provide space for electronics and accommodate an internal air pocket (Fig. 1B, C). This internal pocket allowed for a favorable upright orientation in shallow water (<10 ft) by placing the center of buoyancy above the center of mass. If deeper submersion is required or if bottom-floor navigation is desired, small weights can be added to the inside of the shell to achieve slightly negative buoyancy.

A Top view of the RoboNautilus. B The natural Nautilus, a cephalopod that uses jet propulsion for locomotion. C Bio-inspired robotic system that integrates flexible DEAs to actuate a soft siphon for water expulsion. The system includes an onboard camera, temperature, and salinity senors. An onboard high-voltage power supply circuit enables the robot to be run in an autonomous configuration through cyclic actuation at 1 Hz. The use of DEAs allows for consistent actuation for a given electric field, enabling generation of vortex rings similar to those produced by cephalopods. D Soft actuator within frame showing out of plane deformation at 2 kV. E Time-lapse snapshots of the dyed vortex plume expelled through the siphon, illustrating how the jet flow evolves and forms distinct vortex structures. The resulting vortex profile is given for a stroke ratio of 3.4 and actuation voltage of 1.5 kV. F Autonomous swimming demonstration of the robot shown to move at a speed of 40 cm/min.

At the shell’s anterior opening, we mounted a custom-fabricated dielectric elastomer actuator (DEA) assembly that function as an artificial “mantle" for drawing in and expelling water (Fig. 1D). The DEA assembly is secured to a rigid support frame to ensure consistent actuation during repeated cycles. In cyclically inflating and deflating the elastomer membrane, water is pulled into an internal cavity through the nozzle and then ejected, generating net thrust in a manner similar to that of cephalopods2,21. The robot was shown to move at speed of 40 cm/min (2.5 BL/min) and ran continuously for up to an hour due to the actuators low power consumption (Fig. 1F). To quantify the energetic efficiency of our system we use the cost of transport (COT) (Eq.(1)). P is the power consumed by the actuator (W), m is the mass of the system (kg), and v is the velocity (m/s)22. We obtain a COT of 2.51J kg−1m−1 for our system. This value is lower than previously reported values for a Nautilus (3 Jkg−1m−1)23, highlighting the efficiency of dielectric elastomer actuators and jet propulsion.

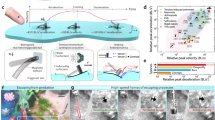

A dedicated onboard high-voltage power supply (Figure S4) (rated up to 2 kV) drives the DEA, while low-voltage systems power a waterproof camera, temperature sensor, and salinity sensor. These additional sensors will enable semi-autonomous operation and environmental monitoring, making the robot suitable for shallow-water exploration or lab-based testing. Underwater soft robots have been effectively used as non-invasive monitoring systems for delicate ecosystems such as coral reefs24. With global temperatures rising, its becoming more important to monitor ocean temperatures and salinity levels25. Thus, to demonstrate our robot’s potential, a temperature and salinity sensor were integrated into the robot as an example. The results are shown in Fig. 2B, C.

A Testing setup used to record underwater thrust measurements. B Thrust as a function of stroke ratio of fluid column displaced and nozzle diameter. C Underwater thrust recorded for DEAs in a 10, 20, and 40 active layer configuration as a function of input voltage. The 20 layer actuator offered the best performance with an average thrust of 17 mN over 5 actuation trials. Increasing the layer count resulted in a stiffer actuator that was unable to displace water out of the nozzle. D Thrust output recorded as a function of actuation frequency for a 20 active layer DEA at an input voltage of 1.5 kV. Thrust decreases for higher frequencies due to the device being unable to achieve a maximum deformation and speed at which the cavity can refill with water. Error bars represent one standard deviation from the mean.

Preliminary tests indicated that the elastomer’s thickness and number of actuator layers significantly influences the thrust output and responsiveness of the siphon. We optimized the design by varying overall actuator thickness to balance large strain output and minimal energy dissipation. In the following sections, we detail how we characterized thrust as a function of actuation voltage and frequency, and discuss how the mantle-like deformation leads to vortex ring formation.

Underwater thrust performance

To quantify the propulsive force generated by the Nautilus-inspired robot, we measured thrust output using a bench-top load cell system (Fig. 3A). A series of (DEAs) was fabricated and tested using Elastosil due to its favorable mechanical response time and dielectric properties. DEAs with 10, 20, and 40-layer configurations were designed to understand the relationship between input voltage, actuation frequency, and thrust generation. Each device had an active area of 16.7 mm2 and an elastomer layer thickness of 50 μm.

A water tank (0.8 m × 0.5 m × 0.35 m) was used for controlled thrust measurements. A custom experimental setup was employed to measure the thrust produced during underwater actuation. This setup incorporated a TAL221 load cell (SparkFun Electronics, Boulder, CO) as outlined in SparkFun tutorials26. The DEAs were mounted in a 3D printed rigid frame that mechanically grounded all four sides of the active area to restrict in-plane motion and maximize out-of-plane deformation. The complete siphon assembly is shown in Figure S3. This configuration ensured that the actuation generated a unidirectional thrust force through the siphon. A high-voltage DC power supply (TREK 610E, Sausalito, California) regulated by a waveform generator (Model 4063B, BK Precision, Yorba Linda, California) applied cyclic signals (0.1–5 Hz) to the DEA. The water was maintained at a constant depth (2.5 cm above the nozzle) to avoid variations in hydrostatic pressure. Figure 3C shows the peak average thrust over five cycles recorded across increasing voltage (0.5–2.0 kV) for three different DEA layer configurations (10-layer, 20-layer, and 40-layer). The 20-layer exhibited the highest net thrust (17 mN at 2 kV) due to a combination of material compliance and energy density contributed by each additional elastomer/electrode layer. The 10-layer device exhibited moderate performance, with a maximum thrust of 11.7 mN. In contrast, the 40-layer design generated visibly smaller displacement due to the increased stiffness associated with more elastomer layers. This is consistent with previous studies that highlight the trade-off between energy density and mechanical constraints in soft actuators12.

In addition to voltage, frequency strongly influenced thrust performance (Fig. 3D). At low actuation frequencies (<1 Hz), the DEA undergoes nearly complete expansion and contraction within each cycle, allowing sufficient time for fluid intake and expulsion, thereby maximizing thrust output. As the frequency increases, the actuator does not fully relax between cycles, resulting in reduced stroke volume and diminished thrust. Two coupled mechanisms cause the phase lag between the voltage input and thrust response. First, the viscoelastic nature of the DEA introduces a time-dependent mechanical delay, whereby the deformation lags behind the applied electric field due to the finite reorientation time of polymer chains27. This effect becomes more pronounced at higher frequencies, where the material cannot respond instantaneously to the input signal. Second, the fluid inertia and added mass effects impose an additional delay as the motion of the actuator must accelerate the surrounding water. The fluid loading resists rapid deformation and becomes increasingly significant as the actuation frequency approaches the resonant range, further shifting the phase lag between electrical excitation and mechanical response. The diminished thrust output at higher frequencies is shown in Fig. 3D and reduced volumetric flow rate is shown in Figure S5B.

Vortex profile

To characterize jet flow generated by our bioinspired propulsion system, we performed flow visualization with red dye injected into the siphon’s internal chamber (Fig. 1E) and particle image velocimetry (PIV). Closely examining the evolving fluid “packets", we could track the formation and pinch-off of vortex rings over time.

A key dimensionless parameter for evaluating vortex ring formation is the stroke ratio, defined as the ratio of the piston (or membrane) stroke length L to the nozzle diameter D. Previous studies on mechanical fluid systems have shown that when \(\frac{L}{D}\approx 4\) a vortex ring typically “pinches off" from the trailing flow, achieving near-optimal circulation and propulsive efficiency28,29. Meanwhile, cephalopods have also been shown to achieve optimal thrust performance under similar conditions30,31,32).For our bioinspired propulsion system we designed three configurations of the siphon frame corresponding to stroke ratios of 1.8, 2.5, and 3.4, observing the resulting flow structures and thrust output (Fig. 3B).

We observed that at a stroke ratio of 3.4, coherent vortex rings formed at the nozzle exit (Fig. 1E, t = 0-3s), separating cleanly from the trailing fluid and propagating downstream. At t = 0 s, the actuator begins contracting, pushing dye-rich water out of the nozzle. By t = 1-2 s, a distinct vortex ring has formed and begun to detach from the shear layer at the nozzle lip. As the ring travels further downstream, subsequent fluid is expelled behind it. Under these conditions, the siphon produced a peak thrust output of 8 mN.

Next, we performed quantitative flow experiments to characterize the fluid dynamics resulting from different nozzle geometries and actuation regimes. The measured velocity and vorticity fields (Fig. 4) reveal the formation of coherent vortex rings during each actuation stroke and show how pulsing frequency governs their evolution, strength, and interaction. These flow features are consistent with thrust trends presented earlier. The evolution of a typical vortex ring generated by a single actuation pulse is depicted in Fig. 4A. As expected, the shear layer rolls up into a toroidal vortex that propagates downstream while entraining ambient fluid. The vortex continues to grow as circulation Γ accumulates, with the majority of the expelled fluid volume entrained into the ring. The clarity and coherence of the resulting structure reflect the efficient conversion of DEA motion into fluid impulse, underscoring the fundamental role of vortex rings in thrust generation. Time-averaged axial velocity profiles, shown in Fig. 4B, were used to estimate bulk Reynolds numbers as Re = UbulkD/ν, yielding values of 264 and 496 for the 12 mm and 16 mm nozzles, respectively. These profiles indicate that the pulsed jet exhibits features similar to a classical steady jet, including a persistent axial core and gradual radial spreading, particularly under moderate pulsing frequencies. The instantaneous flow fields presented in Fig. 4C illustrate the effect of increasing actuation frequency on vortex organization. At low frequencies (e.g., f ≈ 0.5 Hz), pulses occur in isolation, producing distinct vortex rings with negligible interaction. As the frequency increases to 1–2 Hz, the interval between pulses decreases, and consecutive vortex rings begin to interact, forming a ‘vortex ring train.’ These interactions can manifest as mutual induction, deformation of the forming ring, or alterations in vortex trajectory, and in some cases resemble vortex pairing. At higher frequencies (f = 4–5 Hz), the flow transitions to a regime in which individual rings are no longer clearly distinguishable. Instead, the shear layer rolls up into a train of smaller, less coherent vortices, often accompanied by Kelvin-Helmholtz-type instability. At these high frequencies, the vorticity field becomes continuous downstream of the nozzle, and ring structures rapidly dissipate into turbulence within a few nozzle diameters. PIV experiments also revealed circulation Γ, and volumetric flow rate Q(t) in a near-nozzle region obtained from previous vortex structures (Figure S5A, S5B).

Long-term cyclic actuator performance

To evaluate the long-term performance and structural integrity of our DEAs, we performed a series of cyclic actuation experiments under varying high-voltage conditions. These tests aimed to assess how sustained mechanical and electrical loads affect the DEAs’ displacement capabilities and potential failure modes over time.

A planar DEA of 20 active layers was fixed to a rigid frame to prevent lateral expansion. A laser displacement sensor was positioned orthogonally to the geometric center of the membrane (Fig. 5A), measuring the difference between the actuator’s rest position and its out-of-plane deformation during each cycle. Testing proceeded at 1 Hz to capture average displacement cycles at incremental voltage levels and for extended cycling. As shown in Fig. 5B, average displacement increased with rising voltage, reaching a maximum of 3.1 mm at 1.8 kV. The breakdown actuator deformation was about 4 mm at 2.5 kV. This behavior is consistent with previously established models of a DEA membrane33. Using Eq.(3) we get an R2 value of 0.73 when comparing the measured deformation at the center of the actuator. The deviation in our observed behavior arises from a possible nonuniform electric field distribution and inability to account for elastic properties of the elastomer. However, at the upper voltage range, we observed greater standard deviation in displacement measurements, indicative of less consistent surface actuation. These variations suggest that while higher voltage levels achieve greater deformation, reliability and uniformity across the electrode area may diminish when approaching the materials critical dielectric breakdown threshold.

A Displacement measurement principle. The displacement is the difference between the initial and actuation distances measured at the geometric center of the planar actuator. Notice the actuator is bound by a rigid frame. B Average displacement at different voltages. Notice average displacement values are taken across each short testing period. C Accelerated degradation process under high electrical field. (i) displacement across 1000 cycles at 1 Hz. (ii-iv) zoomed in views of displacement deterioration at different time intervals.

To investigate actuator longevity, we subjected the same DEA to 3600 cycles of continuous actuation at a rate of 1 Hz, maintaining a high electric field (>30 V/μm). Figure 5C displays the recorded displacement over the full range of cyclic testing. A 30 W high-voltage power supply provided an electrical field greater than the application scenario. Previous work has shown that current is the primary factor contributing to device degradation34. Under integrated robotic conditions, the DEA would normally be current-limited to around 500 μA, extending device lifespan beyond what we observed here. Gradual decline in peak displacement emerged beyond 220 cycles, correlated with localized electrode wear. To highlight how deterioration evolved over time, Fig. 5C(ii)–(iv) shows snapshots of the displacement waveform at distinct intervals.

This continuous cyclic actuation provides a realistic estimate of device lifetime under conditions more severe than typical usage, helping pinpoint failure mechanisms (e.g., dielectric breakdown, electrode degradation, mechanical fatigue) at high fields.

Discussion

In this work, we explored a bio-inspired approach to underwater jet propulsion by integrating dielectric elastomer actuators (DEAs) within a Nautilus-like shell. The results presented underscore the interplay between mechanical design, material properties, and fluid dynamics in achieving jetting behavior. Through a combination of analytical modeling, fabrication advancements, fluid dynamics experiments, and long-term cyclic testing, we demonstrated how a soft, solid state actuator can replicate key functional aspects of a biological siphon. Our findings provide both a feasibility demonstration of this bioinspired concept and a quantitative framework for future optimization.

We showed that a 3D-printed Nautilus shell with an internal air pocket can maintain an upright orientation in shallow water, enabling stable operation. This design highlights the importance of integrating biological design with engineering solutions to achieve favorable buoyancy and self-righting behavior.

By systematically varying the number of elastomer layers and electrical power input, we identified an optimal balance between membrane compliance and mechanical stiffness. A 20-layer DEA achieved the highest thrust (17 mN at 2 kV), emphasizing the trade-off between large out-of-plane strains (needed for water displacement) and actuator energy density. Our established COT of 2.51 is lower than previously reported studies on the natural Nautilus itself23. The performance of this actuator was tested in the underwater Nautilus robot platform, producing a peak travel speed of 0.66 cm/s (40 cm/min). A jellyfish inspired soft robot powered by fluidic actuators was able to generate an average speed of 0.03 cm/s (1.8 cm/min) in an untethered configuration at a higher actuation voltage of 7 kV35. Another bioinspired soft robot based on single-layer DEAs reported a peak thrust of 0.12 mN and untethered speed of 0.5 cm/s (30 cm/min)36. Our study highlights the effectiveness of pulsed jets and multilayered DEAs for improving underwater propulsion.

Our Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) confirmed that the chosen silicone elastomer (Elastosil P 7670) offers moderate stiffness with relatively low energy loss at an actuation frequency of 1 Hz, making it suitable for efficient, cyclical underwater actuation. Tests performed on actuator degradation under a high electric field ((>30 V/μm) at 1 Hz indicate electrode degradation and dielectric stress due to electrical current as primary failure modes at high voltages. These results affirm that robust, current limiting electronics can extend device longevity.

Dye visualization experiments demonstrated the formation of vortex rings at stroke ratios of approximately 4, consistent with classical fluid dynamics studies of pulsed jets28,32. The formation of vortex rings indicates our system achieves increased propulsive efficiency. PIV testing on the resulting flow structure confirmed earlier findings with thrust output. Low frequency actuation cycles produced coherent vortex rings. Interactions between subsequent jets at higher actuation frequencies obstructed the exit flow where vortices were no longer distinguishable.

The temperature and salinity sensors on the robot are examples of sensors that can be used on the system in the ocean. Other sensors can be implemented to collect different information such as a pressure sensor to record depth. Additionally, we plan to investigate ways of implementing the sensors into the robot’s control algorithm. This will enable fully autonomous movement in an ocean environment.

These findings contribute to the expanding field of bioinspired soft robotics, demonstrating how combining compliant materials, minimal rigid components, and fluid characterization techniques can yield insights into propulsive performance. Such approaches have applications in underwater exploration, surveillance, and environmental monitoring, especially in scenarios where quiet or gentle propulsion is paramount. Future iterations of this design could incorporate soft active elements to control flow rate or thrust vectoring. Thrust output can be optimized through the use of FEA analysis to find optimal actuator geometry that balances strain with energy output. Beyond hardware, actuation timing and profile can be optimized for stronger jets. Drawing inspiration from cephalopod inspired locomotion principles highlights the importance of nature-inspired design strategies for the next generation of underwater systems.

Methods

Analytical model of deformation

The dielectric elastomer actuator in this study undergoes a unique mode of deformation as it is mechanically grounded on all sides. Under no electrical stimuli the DEA starts as a flat two dimensional plane. When high voltage (>1 kV) is applied across the dielectric elastomer, an electric field (Ez) is generated, producing an electrostatic force known as Maxwell stress. This stress compresses the elastomer in the thickness direction and causes the DEA to expand out of plane (Fig. 1G). The elastomer must satisfy the incompressibility condition λ1λ2λ3 = 1. The in-plane strain λ1, λ2 increase during actuation which results in a corresponding decrease in out of plane stretch (λ3). The resulting Maxwell pressure (σ) can be therefore be expressed as:

where ε0 is the permittivity of free space, εr is the relative permittivity of the dielectric material, and \({E}_{z}=\frac{V}{t}\) is the electric field applied. The thickness t is taken to be 50μm for all actuator layers reported in this study.

The out of plane deformation for an electroactive polymer membrane of thickness t and side length a has been derived previously33. This model relates the Maxwell pressure (σx,y) to known material properties: Poisson ratio (ν), Young’s Modulus (E). External pressure (p) is taken to be zero allowing one to model the deformation (z) at the center of the membrane as a function of applied electric field.

To capture the elastomer’s mechanical response under large deformations, we use the strain energy density function, which quantifies the stored energy in the material as it stretches. For incompressible elastomers, the strain energy density function Eq.(4) is commonly expressed in terms of the invariants of the deformation tensor:

I1 and I2 are the first and second invariants of the deformation tensor. C1 and C2 are material constants that define the elastomer’s behavior under strain. The deformation of the DEA is governed by the balance of electrical and mechanical strain energy. The total energy of the system Utotal can be expressed as:

with the strain energy stored in the elastomer, given by:

and the electrical input energy given by:

where A is the active surface area of the DEA containing the electrode. This framework allows us to optimize the performance of the siphon system by choosing materials with favorable mechanical properties and providing high power to the actuator under the constraint of the material’s dielectric breakdown.

Dielectric elastomer actuator fabrication

The composition of the two-part silicone elastomer was Elastosil P 7670 (Wacker, Munich, Germany) mixed in equal weights. The electrodes were prepared by vacuum filtering 2.5 mL of aqueous P3 SWNT inks (Carbon Solutions Inc., Riverside, CA) diluted with isopropanol through polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) filters with pore sizes of 0.2 μm (Spectrum Chemical Mfg. Group). P3 SWNT inks were diluted with DI water using a UV spectrometer (OceanOptics, Orlando, FL) to have 17% optical transmittance at 550 nm wavelength. The filters were then dried at 120 °C in a vacuum oven for 2 h to remove any excess water. 50 μm elastomer layers were cured using a thin film blade coater (Elcometer 4340, Manchester, UK). The electrodes were stamped in between subsequent layers of elastomer and repeated until the desired amount of layers was achieved (Figure S2). Device geometry was controlled by stamping onto a pair of custom cut masks made from Drytac Silicone Release Film (Drytac, Sandston, VA). Actuator release cuts were done using a Universal VLS 3.75 CO2 laser. (Universal Laser Systems, Scottsdale, AZ).

Robot fabrication

All siphon frames and the Nautilus shell were designed in CAD (Solidworks, Waltham, MA) and printed using a fused deposition modeling (FDM) printer (Bambu Labs, Shenzen, China). The Nautilus included an air pocket located in the top portion of the shell. To achieve this, the top portion of the shell was printed with a 10 percent infill.

Dynamic mechanical analysis

A thorough understanding of the elastomer’s mechanical behavior under cyclic loads is crucial for optimizing the actuator’s underwater performance. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) was conducted to evaluate both the storage modulus \({\varepsilon}^{\prime}\) (indicative of the material’s stiffness) and the loss modulus ε″ (reflecting energy dissipation) over a range of frequencies relevant to our actuator’s operational bandwidth. High values for tan(δ) indicate significant energy dissipation, reducing efficiency and slowing down the material’s deformation. Conversely, materials with low tan(δ) exhibit faster response times as more energy is transferred to the fluid for propulsion.

Testing was performed using a DMA850 (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE) in a compression configuration and the results are shown in Figure S1. Temperature was kept fixed at 22 °C to simulate ambient conditions. The test was performed over 0.1 Hz–200 Hz, however the loss tangent of interest was evaluated in the 0.1 Hz to 3 Hz range as this was suitable for the capabilities of the high-voltage power circuit. Based on our DMA findings, we selected Elastosil P 7670, balancing moderate stiffness (\(\varepsilon {\prime} \approx 1.1\) MPa at 1 Hz) with relatively low tan(δ) (0.11). This ensures the membrane can undergo large strain deformations while minimizing energy losses per cycle37,12.

Quantification of vortex ring parameters

Experiments were conducted in a quiescent water tank with a square cross-section measuring 500 mm x 500 mm and a height of 400 mm. The vertical walls were constructed from double-pane, evacuated tempered glass to reduce thermal gradients and minimize optical distortion during imaging. The tank was filled with water maintained at ambient laboratory conditions. Flow was induced through siphon nozzles of diameters D = 12 mm and 16 mm, operated in both single-pulse and continuous modes at discrete actuation frequencies of f = 1–5 Hz, in 1 Hz increments. The resulting velocity fields were measured using planar particle image velocimetry (PIV) in the vertical mid-plane of the nozzle. The measurement domain extended x ∈ [0, 10D] in the streamwise direction and y ∈ [− 3D, 2D] in the wall normal direction, with the coordinate origin located at the nozzle center. Silver coated tracer particles of 44 μm diameter were used for flow seeding and were illuminated by a dual-cavity 532 nm Nd:YAG laser. A 2.3 MP high-speed camera acquired images at a sampling rate of 100 Hz. For each case, 500 velocity fields were obtained using a multi-pass cross correlation algorithm, with a final interrogation window of 32 x 32 pixels and 50% overlap, resulting in a spatial resolution of approximately 1.4 mm.

High-voltage circuit

The untethered high-voltage power supply and switching circuitry are shown in Figure S4. An Arduino Nano microcontroller supplies control signals to the switching circuitry. The HV DC-DC boost converter (SMHV0520, HVM Technology Inc.) converts a 5 V input to a 2 kV output used to power the actuators. OR-100 (HVM Technology Inc.) optorelay is used to rapidly charge and discharge the DEA. IXTF02N450 (IXYS) high voltage MOSFET used for rapidly discharging the DEA. Linear voltage regulator (LM2940T-5.0/NOPB) used to step down the 7.4 V supply provided by two series LiPo batteries to 5 V.

Salinity and temperature sensing

To simulate a field scenario for the test robot, a temperature sensor and simplified salinity sensor were integrated into the mock robot. Simplified versions of both sensors were assembled for demonstration purposes. For the tests, they were controlled by a separate Arduino Uno (Arduino, Italy) located in a hollow top cavity shown in Fig. 1D. To ensure all electronics were waterproof, they were sealed in Ecoflex 00-35 Fast silicone rubber (Smooth-on, PA, USA) along with the sensors.

The temperature sensor was a TMP36 (Adafruit, New York City, NY) that was potted in silicone, leaving the sensing portion exposed to the water. A simplified salinity sensor was assembled using a 1k ohm resistor, two 22 AWG wires, and a single 3D printed mount. The Arduino was programmed to use the 1 k ohm resistor as a reference to calculate the resistance between the two submerged prongs. The 3D-printed mount ensured the wires remained at a fixed distance of 3 mm.

The resistance was used to calculate the Practical Salinity of the water using the Thermodynamic Equation of Seawater - 2010 (TEOS 10), an international standard for seawater property calculations. The equation utilizes conductivity of the salt solution, temperature, and pressure to determine Practical Salinity. Conductivity was derived from the measured resistance and the wire configuration. To reduce noise, a fixed temperature was used for the TEOS 1038 calculation for salinity so only the measured resistance was used. To ensure the salinity sensor worked properly, it was calibrated with a mixture of 20 mL deionized water (DI) and 0.7 g of salt. This mixture has a practical salinity of 35 g/kg which is about the average value of the ocean39.The Arduino was connected to a computer and continuously collected data in an underwater test.

Data availability

Processed data supporting the findings of this study are available in the Article and the Supplementary Information. Raw data is available by request from the Authors. No purpose-made code was produced or utilized during the current study.

Code availability

No purpose-made code was produced or utilized during the current study.

References

Neil, T. R. & Askew, G. N. Swimming mechanics and propulsive efficiency in the chambered nautilus. R. Soc. Open Sci. 5, 170467 (2018).

Bi, X. & Zhu, Q. Numerical investigation of cephalopod-inspired locomotion with intermittent bursts. Bioinspiration Biomim. 13, 056005 (2018).

O’dor, R., Forsythe, J., Webber, D., Wells, J. & Wells, M. Activity levels of nautilus in the wild. Nature 362, 626–628 (1993).

Chamberlain Jr, J. A. Locomotion in ancient seas: constraint and opportunity in cephalopod adaptive design. Geobios 26, 49–61 (1993).

Lee, J. S. et al. Origin and dynamics of vortex rings in drop splashing. Nat. Commun. 6, 8187 (2015).

Li, G. et al. Bioinspired soft robots for deep-sea exploration. Nat. Commun. 14, 7097 (2023).

Bang, J. et al. Bioinspired electronics for intelligent soft robots. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 1, 597–613 (2024).

Laschi, C. & Mazzolai, B. Bioinspired materials and approaches for soft robotics. Mrs Bull. 46, 345–349 (2021).

Christianson, C. et al. Cephalopod-inspired robot capable of cyclic jet propulsion through shape change. Bioinspiration Biomim. 16, 016014 (2020).

Serchi, F. G., Arienti, A. & Laschi, C. Biomimetic vortex propulsion: toward the new paradigm of soft unmanned underwater vehicles. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 18, 484–493 (2012).

Zhang, R. et al. A cephalopod-inspired soft-robotic siphon for thrust vectoring and flow rate regulation. Soft Robot. 8, 416–431 (2021).

Pelrine, R., Kornbluh, R., Pei, Q. & Joseph, J. High-speed electrically actuated elastomers with strain greater than 100%. Science 287, 836–839 (2000).

Wang, Z., Xu, Q., Zhou, Y., Li, G. & He, B. Effect of temperature and pre-stretch on the dynamic performance of dielectric elastomer minimum energy structure. Sci. Rep. 14, 15411 (2024).

Shintake, J., Cacucciolo, V., Shea, H. & Floreano, D. Soft biomimetic fish robot made of dielectric elastomer actuators. Soft Robot. 5, 466–474 (2018).

Christianson, C., Goldberg, N. N., Deheyn, D. D., Cai, S. & Tolley, M. T. Translucent soft robots driven by frameless fluid electrode dielectric elastomer actuators. Sci. Robot. 3, eaat1893 (2018).

Godaba, H., Li, J., Wang, Y. & Zhu, J. A soft jellyfish robot driven by a dielectric elastomer actuator. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 1, 624–631 (2016).

Duduta, M., Wood, R. J. & Clarke, D. R. Multilayer dielectric elastomers for fast, programmable actuation without prestretch. Adv. Mater. 28, 8058–8063 (2016).

Duduta, M., Hajiesmaili, E., Zhao, H., Wood, R. J. & Clarke, D. R. Realizing the potential of dielectric elastomer artificial muscles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 116, 2476–2481 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Controlled flight of a microrobot powered by soft artificial muscles. Nature 575, 324–329 (2019).

Berlinger, F. et al. A modular dielectric elastomer actuator to drive miniature autonomous underwater vehicles. 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) 3429–3435 (2018).

Anderson, E. J. & Grosenbaugh, M. A. Jet flow in steadily swimming adult squid. J. Exp. Biol. 208, 1125–1146 (2005).

Coe, M. & Gutschmidt, S. Cost of transport is not the whole story-a review. Ocean Eng. 313, 119332 (2024).

O’dor, R. & Webber, D. Invertebrate athletes: trade-offs between transport efficiency and power density in cephalopod evolution. J. Exp. Biol. 160, 93–112 (1991).

Katzschmann, R. K., DelPreto, J., MacCurdy, R. & Rus, D. Exploration of underwater life with an acoustically controlled soft robotic fish. Sci. Robot. 3, eaar3449 (2018).

Durack, P. J., Lee, T., Vinogradova, N. T. & Stammer, D. Keeping the lights on for global ocean salinity observation. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 228–231 (2016).

Electronics, S. Load cell amplifier hx711 breakout hookup guide https://learn.sparkfun.com/tutorials/load-cell-amplifier-hx711-breakout-hookup-guide/all. Accessed: 07/21/2024.

Tan, M. W. M., Thangavel, G. & Lee, P. S. Enhancing dynamic actuation performance of dielectric elastomer actuators by tuning viscoelastic effects with polar crosslinking. NPG Asia Mater. 11, 62 (2019).

Gharib, M., Rambod, E. & Shariff, K. A universal time scale for vortex ring formation. J. Fluid Mech. 360, 121–140 (1998).

Krueger, P. S. & Gharib, M. The significance of vortex ring formation to the impulse and thrust of a starting jet. Phys. fluids 15, 1271–1281 (2003).

Dabiri, J. O. & Gharib, M. The role of optimal vortex formation in biological fluid transport. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 272, 1557–1560 (2005).

Stewart, W. J., Bartol, I. K. & Krueger, P. S. Hydrodynamic fin function of brief squid, lolliguncula brevis. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 2009–2024 (2010).

Bartol, I. K., Krueger, P. S., Stewart, W. J. & Thompson, J. T. Pulsed jet dynamics of squid hatchlings at intermediate reynolds numbers. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 1506–1518 (2009).

Rosset, S., Niklaus, M., Dubois, P. & Shea, H. R. Mechanical characterization of a dielectric elastomer microactuator with ion-implanted electrodes. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 144, 185–193 (2008).

Li, A. et al. Data-driven long-term energy efficiency prediction of dielectric elastomer artificial muscles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2406710 (2024).

Christianson, C. et al. Jellyfish-inspired soft robot driven by fluid electrode dielectric organic robotic actuators. Front. Robot. AI 6, 126 (2019).

Cheng, T. et al. Untethered soft robotic jellyfish. Smart Mater. Struct. 28, 015019 (2018).

Carpi, F., Chiarelli, P., Mazzoldi, A. & De Rossi, D. Electromechanical characterisation of dielectric elastomer planar actuators: comparative evaluation of different electrode materials and different counterloads. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 107, 85–95 (2003).

McDougall, T. et al. The international thermodynamic equation of seawater 2010 (teos-10): Calculation and use of thermodynamic properties. Global ship-based repeat hydrography manual, IOCCP report no14 (2009).

Millero, F. J., Feistel, R., Wright, D. G. & McDougall, T. J. The composition of standard seawater and the definition of the reference-composition salinity scale. Deep Sea Res. Part I: Oceanographic Res. Pap. 55, 50–72 (2008).

Acknowledgements

D.F., S.S. and A.W. thank the Connecticut NASA Space Grant Consortium for graduate fellowship support. M.D. thanks the National Institute for Undersea Vehicle Technology (NIUVT) for experimental resources and student support. Additional experimental support was provided by a prototyping award from the Mid-Atlantic Hub of the Air Force Resesarch Laboratory. The authors wish to thank Tirth Thakar and Dr. Codrin Tugui for helpful discussions regarding elastomer preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.F. and M.D. developed the artificial siphon and nautilus robot concept. D.F. performed thrust measurements. D.F. and S.S. fabricated the dielectric elastomer actuators, and A.L. characterized the devices. D.F., S.S. and A.Y. performed underwater testing of the robot. A.Y. integrated the temperature and salinity sensors. A.W. and A.L. developed and integrated the power electronics. D.F. wrote the main manuscript text, and made the figures 1, 2, 3 and 5. S.K., Y.W., and L.C. made figure 4 and helped with PIV testing/analysis. M.D. coordinated the research, and edited the manuscript, figures and videos. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Flores, D., Sandhu, S., White, A. et al. RoboNautilus: a cephalopod-inspired soft robotic siphon for underwater propulsion. npj Robot 3, 17 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-025-00035-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-025-00035-2