Abstract

Marine spatial planning (MSP) and marine protected area (MPA) planning are two distinct area-based management processes that are often conflated. While engaging in MPA planning is crucially important for biodiversity conservation and localized sustainable use, it cannot bring the benefits that larger scale MSP can deliver. Confusing the two can lead not only to missed opportunities to support ocean sustainability, but also to inefficiencies and even conflict. Here, we clearly define and distinguish each approach, then discuss opportunities to optimise synergies, especially under rapidly changing climate. MSP can support conservation efforts by taking the broader context into account, while integrating conservation and MPA planning into MSP allows for the maintenance of ocean health—always a core goal of marine management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Marine spatial planning (MSP) and marine protected area (MPA) planning are two distinct area-based management processes used worldwide to support sustainable ocean use and conservation1,2. Both approaches are paramount for improving marine management, particularly in the face of increasing anthropogenic impacts on coupled ocean–human health3,4,5. While MSP and MPA planning share a variety of similarities, they target different goals and objectives, and use different methodologies, tools, and practitioner skillsets. For instance, planning for sustainable use and a sustainable blue economy through MSP is vastly different from planning to reach conservation goals and targets through MPA planning. They also have different “maturity” levels, with formal MSP processes emerging only over the past two decades6,7; in contrast to MPA planning that has been undertaken for 50 years or more. From a policy standpoint, these two approaches are also perceived very differently by ocean users, decision-makers, and the general public. Yet, MSP and MPA planning concepts are often used interchangeably in multiple contexts8,9,10, leading to confusion, conflict, and missed opportunities to achieve ocean sustainability (Box 1).

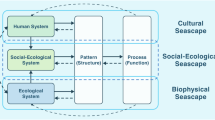

As the world moves to incorporate climate change considerations into planning, the lack of clarity around these distinct approaches may sow further confusion and limit our pathways to sustainable solutions. To ensure progress, there is an urgent need to dispel confusion about these approaches and provide a clear pathway for practitioners to adopt “climate-smart” approaches in MSP and MPA planning practices. Both MSP and MPA planning are affected by climate-driven changes in marine environments (and in how humans use these environments) and both approaches must become climate-smart by necessity11,12,13. Therefore, it is crucial to distil the best contributions of each approach and maximise their benefits while leveraging complementarity. Here, we clearly distinguish MSP from MPA planning (Fig. 1) (and climate-smart MSP from climate-smart MPA planning), critically evaluate the key contributions from each approach, and identify future opportunities to optimise synergies between them to support ocean sustainability.

Defining MSP and MPA planning

MSP is a multi-sectoral and multi-objective process that broadly targets sustainable ocean use and blue economy development by balancing ecological, social, and economic dimensions (Fig. 1). While MSP takes many forms in practice (Box 2) and is highly context-dependent, the most well-established definition of MSP is from the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO-IOC). UNESCO-IOC guidance defines MSP as “a public process of analysing and allocating the spatial and temporal distribution of human activities in marine areas to achieve ecological, economic, and social objectives that are usually specified through a political process”2. Simply put, MSP seeks to integrate and balance existing and emergent human uses, to minimise conflicts and to foster compatibility among them, as well as between such uses and the environment. Therefore, MSP offers a vehicle for a structured consideration of economic, social and environmental objectives within a given marine area. Effective MSP is ecosystem-based (considering the entire ecosystem, including humans, and balancing ecological, economic, and social goals), integrated (across sectors, agencies and levels of government), area and place-based (focusing on a specific area with a specific meaning14), adaptive (able to deliver despite changing conditions), strategic (that is, focused on the long term), and—crucially—participatory (with the active involvement of rightsholders and stakeholders)2,15. MSP involves creating a shared vision for the future across many divergent viewpoints and aspirations, from multiple stakeholders and sectors. MSP is usually done at broad geographical scales, encompassing entire bioregions or national jurisdictions7, with the potential to be applied in larger spaces, namely in areas beyond national jurisdiction16,17.

Conversely, MPA planning focuses explicitly on biodiversity protection and meeting conservation goals. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), a protected area is “a clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values”18 (Box 2). IUCN guidelines highlight, through protected area management categories, that there is a “continuum” of MPAs. The same is reflected in the MPA Guide1, a newer framework intended to complement the IUCN categories by providing a typology based on the degree of implementation and protection level. Both cases include MPAs which are deemed “fully protected” or “strictly protected”, being “no take” areas that prohibit all extractive uses1,18. Other MPAs in these typologies are referred to as “multiple-use” MPAs and allow for varying extents of extractive, recreational, traditional, subsistence or cultural uses, as well as shipping and military uses. While allowing differing degrees of human use, these various types of MPAs19 aim to limit uses that are destructive or incompatible with nature protection1. In effect, not all existing or potential human uses are considered nor accommodated in multiple-use MPAs exactly because the goal is to protect biodiversity and delivery of ecosystem services. Regardless of what category is implemented and objectives are being targeted, MPAs focus on areas with distinctive biological features and ecological values. MPAs also tend to cover only small parts of a nation’s marine estate—with the exception of a few large MPAs in international waters, or large MPAs covering the entire maritime jurisdiction of island states (extending up to 200 nautical miles offshore)20,21.

Pinpointing overlaps and conflation

The frequent conflation of MSP and MPA planning likely stems from their similarities and frequent overlaps (Fig. 1). First, both spatial planning approaches share concerns over sustainable ocean use and conservation and often co-exist in space. Second, MSP generally intersects with MPA planning, as allocating space for an MPA or MPA networks can be (and, often, is) one of the outcomes of MSP. Third, when MSP initiatives are defined as “ecosystem-based” or “conservation-ready”22,23, they can be confused with conservation planning specifically for MPAs (Box 2). Conservation-ready MSP recognises conservation as the foundation for the entire planning process and views conservation policy as a way to ensure ocean use is sustainable and benefits society in the long term. Thus, ecosystem-based and conservation-ready MSP may be misconceived as a tool for creating new MPAs as their ultimate goal. For such reasons, many sectors have viewed MSP as “marine protected areas spelt differently”24. Fourth, the original zoning scheme of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park in Australia is considered by many (and often referred to) as a “pioneer example” of MSP25,26, which leads to further confusion.

While most MPA planning optimises conservation at small scales, MSP addresses multiple objectives, integrates diverse stakeholder perspectives, and provides a broader framework that intends to support both conservation goals and a sustainable blue economy. In the following paragraphs we address a number of aspects that explain how these processes differ, and how they can be undertaken synergistically. These distinctions between MSP and MPA planning include differences in: use of zonation, scale (temporal and spatial), “systems view”, stakeholder involvement, and the integration of climate change considerations. Recognising these distinctions can shine light on how to best utilise and support these processes (Fig. 1).

Scale

MSP tends to operate at broader spatial and temporal scales than MPA planning. As noted above, MSP generally takes place at a national scale, while MPAs tend to cover small, isolated bits of areas under national jurisdiction. As for the temporal dimension, MSP is more forward-looking than MPA planning by design. For example, while both approaches want to ensure effectiveness over the long term, generally only MSP uses scenario development and visioning processes to analyse imagined futures15,27. The analysis of future conditions is one of the “key steps” of developing MSP2, which requires projecting current trends in ocean use, identifying possible alternative futures, defining the future we want, and establishing a plan to achieve it. Indeed, several authors acknowledge that MSP is all about the future, a way to look forward and to guide human action toward a vision for tomorrow’s ocean (e.g., refs. 27,28,29,30). By contrast, MPA planning focuses on existing evidence of conservation benefits (e.g., biodiversity hotspots, nursery areas of key species) identified and monitored at present and in the past31. Also, MSP is proactive2,32,33, and is about maintaining a dynamic process that is continuous and iterative as it aims to optimise ocean health to benefit people over the long term11, while MPAs (once designated) are fixed and subjected to management plans to implement protection zonation.

Zonation

Both MSP and MPA planning use zonation. Developing a zoning plan is a key task in MSP development according to the UNESCO-IOC MSP guide2. MSP zoning includes locating and designing zones; designing systems of permits, licences, and use rules within each zone; establishing compliance mechanisms; and creating programmes to monitor, review, and adapt the zoning system2. Similarly, some multiple-use MPAs have zoning schemes to establish where specific uses are allowed and where certain uses may be prohibited8. In effect, MPA planning entails two main tasks: (1) identifying the location and shape of an MPA or a network of MPAs (i.e., where MPAs are to be located); and (2) designing the “interior” of an MPA (i.e., how different areas within such MPA are to be managed)28. One could argue that MPA planners adopt a “MSP” approach within MPA boundaries. However, while in MPA planning zonation largely focuses on the restriction of certain ocean uses that may hinder conservation, in MSP the allocation of areas to certain uses is based on the assessment of potential conflicts and compatibilities among existing/future human uses (e.g., fisheries, tourism, shipping) and between such uses and the environment. Further, MPA planning is focused on what happens within its boundaries, while MSP is by design meant to account for transboundary effects34,35.

Systems view

This relates to the fact that the skillsets needed for MPA planning are quite different from MSP. A systems view is commonly absent in MPA planning. Such an approach requires the recognition of complex social-ecological dynamics and interactions; these considerations include economic costs and benefits but extend beyond to other measures of human well-being. Social–economic–ecological processes support the delivery of ecosystem goods and services, and a holistic focus on all of them can lead to an integrated vision of planning that crosses biophysical (e.g., ocean–land), social, economic, and political boundaries11. Contrary to MSP processes8, professional planners are rarely employed in MPA planning, and the full consideration of marine and coastal values, the identification of the full suite of pressures affecting these values, and the full range of existing and emergent maritime uses are generally not considered—although there are exceptions (e.g., ref. 36). In isolation, MPAs often create “islands of protection” in a sea of degradation and user conflict because the planning spotlight used for siting and designing MPAs is focused on priority sites and not the broader social-ecological context37. While systematic conservation planning (Box 2) can address this gap, there are still challenges to how MPA planning effectively integrates social and economic dimensions38,39. Under these circumstances, challenges can arise and result in potentially damaging human uses that are simply displaced (or partially displaced) to areas outside MPAs rather than managed, which can have unintended negative consequences39. Also, pressures from other drivers outside MPAs may persist, as they cannot be managed through MPA planning36,40. These “system effects” are something that MSP, with its broader strategic framework, systems view and recognition of complex social–ecological connections, can consider and mitigate11. By its very nature, the process of MSP allows thinking through connections, single cause-effect relationships, and the functional relationships between multiple causes and related multiple effects36,41.

Stakeholders

By virtue of scale alone, MSP implicitly engages a broader range of stakeholder groups. But it is more than just a question of scale. MSP is a process designed to allow for the integration of all voices at the same table, develop a common understanding, establish a joint vision, and use planning tools to achieve that vision2, in a way that MPA planning alone cannot. While some ocean uses are addressed in MPA planning (e.g., local fisheries, sustainable tourism), the full multiplicity of stakeholders and sectors are usually not holistically considered and integrated as in MSP, especially where user groups are not directly affected by a proposed MPA. Involving the full range of key stakeholders in MSP development from the onset is essential, mainly because MSP aims to achieve multiple objectives (social, economic and ecological), and for that purpose, must reflect as many expectations, opportunities and conflicts occurring in the planning area as possible. Properly engaging the full range of stakeholders is key to MSP acceptance, adoption and enforcement. Planning decisions need to be grounded in what is acceptable by society, what is cost-effective, and what can be implemented by various regulatory authorities to succeed in the long term39. If maintaining a fully functioning ocean is the goal of planning, a critical component will be to protect the ecosystem functions and the ecologically important areas that bring value to all stakeholders.

Climate change

Finally, to be effective in the long term, both MSP and MPA planning must properly integrate climate change. As climate-related drivers alter marine environments, they affect how people relate to and benefit from the ocean5,42. Indeed, areas where human activities are most amenable to occur today will likely be different in the near future. The same applies to areas with distinctive biological features and ecological values that are protected under MPAs. Both MSP and MPA planning initiatives must, therefore, anticipate these climate-induced changes, respond to them and adapt accordingly, while enabling sustainable and equitable ocean use11,12,29,43. “Climate-smart MSP” is now recognised as crucial by international organisations such as UNESCO, the United Nations Environment Programme, the European Commission, and the World Bank44,45,46. To be climate-smart, MSP must integrate climate-related knowledge, be flexible and adapt to changing conditions, and support climate adaptation and mitigation actions11,29 (Box 2). This includes, for example, developing proactive future-looking plans, using modelling tools and vulnerability analyses, balancing flexibility with legal certainty, and understanding system interactions and dynamics11. At the same time, with climate change altering ecological conditions and diminishing ecosystem health at an ever-increasing pace, creating static areas of protection will not lead to lasting conservation outcomes. As a result, there has been a push to develop guidelines for designing “climate-smart MPAs”12,43 (Box 2). Such guidelines recognise that networks of MPAs must protect critical sites, including climate refugia47,48, and that adapting to climate change requires transboundary management and coordination of shared ecoregions12. Climate-smart MPA planning can, therefore, use some of the same approaches and tools as climate-smart MSP. For instance, climate-smart MPA planning can encompass moving or dynamic areas of protection, establish monitoring programmes that allow for adaptation of management, and protect marine refugia located in areas that may be less important today, but exceedingly important in the future49,50. However, while climate-smart MPA planning tends to focus on the biophysical dimension of change12, climate-smart MSP requires broader knowledge of what will change (how, when and where) at both biophysical and human levels, together with the expected social, economic, political, and environmental consequences of such change11. Also, by being multi-sectoral, climate-smart MSP has more tools (e.g., regulations, policies) at its disposal to implement adaptive strategies.

Leveraging synergies and moving forward

We advocate that clearly recognising MSP and MPA planning as serving different goals and resulting in different outcomes is a prerequisite to moving from conflation towards leveraging synergies between the two (and by extension, between climate-smart MSP and MPA planning). Clearly, both approaches are fundamental to supporting sustainable ocean use and conservation, particularly under change, while responding to different challenges. MSP and MPA planning are not interchangeable (nor competing) approaches. MSP is not intended to substitute MPA planning or promote economic growth at the expense of biodiversity, ecosystem health, and collective human well-being. The processes are mutually synergistic, and ideally should work in parallel—and be further integrated (Box 3)—to support ocean sustainability under dramatic and rapid change.

MSP can leverage MPA planning to achieve specific conservation goals. MPA planning can benefit from MSP by allowing planners to consider what is happening beyond the boundaries of protection, with conservation interests ensured a “seat” at the table in the broader management of ocean use, and ways to mediate conflicts37. Indeed, the broader scope of MSP—regarding scale, stakeholder involvement, the ability to take a systems view, or the integration of climate-smart approaches—offers opportunities to expand MPA planning. At the same time, integrating MPA planning with MSP ensures that the critical focus on ecosystem health remains central to the planning process, and does not come second to economic goals. A central emphasis on ocean health is particularly crucial to the achievement of global commitments such as the ones from the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Global Biodiversity Framework51 (including Target 1 on integrated spatial planning and management), the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, or the Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction—the BBNJ Agreement16,52.

Climate-smart MPA planning and MSP can thus be synergistic. Incorporating conservation planning into climate-smart MSP can provide the foundation for more effective and just management, alongside boosting biodiversity protection, in areas where human dependence on the sea is strong11. Moving away from community needs on the coast, climate-smart MSP has considerable potential to support the implementation of the BBNJ Agreement, as it can provide a framework for enhanced cooperation and adoption of area-based management tools16. In the jurisdiction of coastal nations and beyond, climate-smart MSP can support existing and new MPAs and can advance MPA planning through multiple pathways (Fig. 2). These include: (1) highlighting areas where new MPAs (and networks of MPAs) need to be established to meet a variety of conservation objectives under a changing ocean; (2) setting the stage for dynamic MPAs as part of dynamic ocean planning and management; (3) furthering our understanding of social-ecological systems to help redesign or adapt existing MPAs to be more effective; (4) promoting both natural (passive) recovery as well as restoration of ecosystem functioning and ocean health53,54; (5) allowing examination of trade-offs between use and conservation, and the sustainability of use over time, in light of climate change; (6) strategically allocating a full range of uses in such a way that conflicts are minimised and both human well-being and a sustainable blue economy are enhanced; and (7) helping local communities, the public, and decision-makers to anticipate—and adapt to—potential futures.

Acknowledging differences and complementarities between MSP and MPA planning, and adopting a climate-smart approach in both MPA planning and MSP, are key to sustainability in a changing ocean. Leveraging synergies among these processes and their outcomes is fundamental to achieving multiple conservation objectives while fostering social benefits, and will help build cooperation among existing conventions and initiatives. By contrast, conflating the two approaches is problematic, as it can lead to missed opportunities and inhibit necessary MPA planning and effective MSP. Mutual recognition of the benefits of undertaking both MPA planning and MSP is needed in their respective policy arenas. In addition, since planning is only as good as the management that flows from it, climate-smart MPAs and marine spatial plans will also require implementation by practitioners around the world and long term support from marine management agencies. Providing that support to translate plans to action will amplify the strengths of these processes and contribute to ensuring a sustainable ocean for all.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Grorud-Colvert, K. et al. The MPA guide: a framework to achieve global goals for the ocean. Science 373, eabf0861 (2021).

Ehler, C. N. & Douvere, F. Marine Spatial Planning: A Step-by-Step Approach toward Ecosystem-Based Management (UNESCO-IOC, 2009).

Rockström, J. et al. The planetary commons: a new paradigm for safeguarding Earth-regulating systems in the anthropocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 121, e2301531121 (2024).

Halpern, B. S. et al. Recent pace of change in human impact on the world’s ocean. Sci. Rep. 9, 11609 (2019).

Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2023).

State of the Ocean Report (UNESCO-IOC, 2024).

Ehler, C. N. Two decades of progress in marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy 132, 104134 (2021).

Vaughan, D. & Agardy, T. Marine protected areas and marine spatial planning – allocation of resource use and environmental protection. Mar. Protected Areas 13–35 (2020).

Trouillet, B. & Jay, S. The complex relationships between marine protected areas and marine spatial planning: Towards an analytical framework. Mar. Policy 127, 104441 (2021).

Santos, D. A. et al. (Mis) Perceptions of marine spatial planning in changing polar regions (2025). [Manuscript submitted for publication, see www.plantproject.eu].

Frazão Santos, C. et al. Key components of sustainable climate-smart ocean planning. npj Ocean Sustain. 3, 10 (2024).

Arafeh-Dalmau, N. et al. Integrating climate adaptation and transboundary management: guidelines for designing climate-smart marine protected areas. One Earth 6, 1523–1541 (2023).

Hannah, L. et al. To save the high seas, plan for climate change. Nature 630, 298–301 (2024).

Wedding, L. M. et al. Integrating the multiple perspectives of people and nature in place-based marine spatial planning. npj Ocean Sustain. 3, 43 (2024).

Reimer, J. M. et al. The marine spatial planning index: a tool to guide and assess marine spatial planning. npj Ocean Sustain. 2, 15 (2023).

Frazão Santos, C. et al. Taking climate-smart governance to the high seas. Science 384, 734–737 (2024).

Wright, G. et al. Marine spatial planning in areas beyond national jurisdiction. Marine Policy 132, 103384 (2021).

Day, J. C. et al. Guidelines for Applying the IUCN Protected Area Management Categories to Marine Protected Areas (IUCN, 2019).

Gill, D. A. et al. A diverse portfolio of marine protected areas can better advance global conservation and equity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 121, e2313205121 (2024).

Pike, E. P. et al. Ocean protection quality is lagging behind quantity: applying a scientific framework to assess real marine protected area progress against the 30 by 30 target. Conserv. Lett.17, e13020 (2024).

Protected Area Profiles from the World Database on Protected Areas (UNEP-WCMC, 2025).

Reimer, J. et al. Conservation ready marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy 153, 105655 (2023).

Ansong, J., Gissi, E. & Calado, H. An approach to ecosystem-based management in maritime spatial planning process. Ocean Coastal Manage.141, 65–81 (2017).

Frazão Santos, C. et al. Ocean planning and conservation in the age of climate change: a roundtable discussion. Integr. Organis. Biol.6, obae037 (2024).

Frazão Santos, C. et al. Marine Spatial Planning. World Seas: an Environmental Evaluation (Elsevier, 2019).

Day, J. C. Zoning—lessons from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. Ocean Coastal Manage.45, 139–156 (2002).

Gissi, E., Fraschetti, S. & Micheli, F. Incorporating change in marine spatial planning: A review. Environ. Sci. Policy 92, 191–200 (2019).

Agardy, T. Ocean Zoning: Making Marine Management More Effective (Earthscan, 2010).

Frazão Santos, C. et al. Integrating climate change in ocean planning. Nat. Sustain. 3, 505–516 (2020).

Edwards, R. & Evans, A. The challenges of marine spatial planning in the Arctic: results from the ACCESS programme. Ambio 46, 486–496 (2017).

Secretariat for the Convention on Biological Diversity. Article 8. In-Situ Conservation. Convention on Biological Diversity: Text and Annexes (CBD, 2011).

A Marine Spatial Planning Framework for Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction. UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC, 2019).

Reimer, J. M., Devillers, R., Ban, N. C., Westhead, M. & Claudet, J. in A Research Agenda for Sustainable Ocean Governance (eds Alger, J. & Sumaila, U. J.) Ch. 14 (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2025).

Jay, S. et al. Transboundary dimensions of marine spatial planning: fostering inter-jurisdictional relations and governance. Marine Policy 65, 85–96 (2016).

Van Tatenhove, J. P. M. Transboundary marine spatial planning: a reflexive marine governance experiment?. J. Environ. Policy Plan.19, 783–794 (2017).

Carlucci, R. et al. Managing multiple pressures for cetaceans’ conservation with an Ecosystem-Based Marine Spatial Planning approach. J. Environ. Manage.287, 112240 (2021).

Agardy, T., Di Sciara, G. N. & Christie, P. Mind the gap: addressing the shortcomings of marine protected areas through large scale marine spatial planning. Marine Policy 35, 226–232 (2011).

Giakoumi, S. et al. Advances in systematic conservation planning to meet global biodiversity goals. Trends Ecol. Evol. 40, 395–410 (2025).

Halpern, B. S., Lester, S. E. & McLeod, K. L. Placing marine protected areas onto the ecosystem-based management seascape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107, 18312–18317 (2010).

Menegon, S. et al. A modelling framework for MSP-oriented cumulative effects assessment. Ecol. Indicat.91, 171–181 (2018).

Hammar, L. et al. Cumulative impact assessment for ecosystem-based marine spatial planning. Sci. Total Environ.734, 139024 (2020).

Pecl, G. T. et al. Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: impacts on ecosystems and human well-being. Science 355, eaai9214 (2017).

Brito-Morales, I. et al. Towards climate-smart, three-dimensional protected areas for biodiversity conservation in the high seas. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 402–407 (2022).

Climate-Informed Marine Spatial Planning (The World Bank, 2021).

Updated Joint Roadmap to Accelerate Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning Processes Worldwide - MSProadmap (2022-2027) (UNESCO-IOC & European Commission, 2022).

MSPglobal Policy Brief: Climate Change and Marine Spatial Planning (UNESCO-IOC, 2021).

Buenafe, K. C. V., et al. A metric-based framework for climate-smart conservation planning. Ecol. Appl. 33, e2852 (2023).

Buenafe, K. C. V. et al. Current approaches and future opportunities for climate-smart protected areas. Nat. Rev. Biodivers. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44358-025-00041-0.

Maxwell, S. M. et al. Dynamic ocean management: defining and conceptualizing real-time management of the ocean. Mar. Policy 58, 42–50 (2015).

Maxwell, S. M., Gjerde, K. M., Conners, M. G. & Crowder, L. B. Mobile protected areas for biodiversity on the high seas. Science 367, 252–254 (2020).

Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. CBD/COP/DEC/15/4 (CBD, 2022).

Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction (United Nations, 2024).

Manea, E., Agardy, T. & Bongiorni, L. Link marine restoration to marine spatial planning through ecosystem-based management to maximize ocean regeneration. Aquatic Conserv. 33, 1387–1399 (2023).

Wedding, L. M. et al. Global biodiversity recovery requires synergies between restoration and planning (2025). [Manuscript submitted for publication, see www.oxfordseascapeecologylab.com].

ATCM. Marine Spatial Planning for a Sustainable and Climate-Resilient Antarctic Ocean. Information Paper IP167. www.ats.aq/devAS/Meetings/Past/97 (2024).

Final Report of the Forty-Sixth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting. Kochi, India, 20-30 May 2024. Volume I (Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty, 2024).

Directive 2014/89/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 2014, Establishing a Framework for Maritime Spatial Planning (European Union, 2014).

Rilov, G. et al. A fast-moving target: achieving marine conservation goals under shifting climate and policies. Ecol. Appl. 30, e02009 (2020).

Kirkfeldt, T. S. & Frazão Santos, C. A review of sustainability concepts in marine spatial planning and the potential to supporting the UN sustainable development goal 14. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 713980 (2021).

100% Sustainable Ocean Management: An Introduction to Sustainable Ocean Plans (High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, 2021).

Qiu, W. & Jones, P. J. S. The emerging policy landscape for marine spatial planning in Europe. Mar. Policy 39, 182–190 (2013).

Pressey, R. L., Cabeza, M., Watts, M. E., Cowling, R. M. & Wilson, K. A. Conservation planning in a changing world. Trends Ecol. Evol.22, 583–592 (2007).

Margules, C. R. & Pressey, R. L. Systematic conservation planning. Nature 405, 243–253 (2000).

Ban, N. C. & Klein, C. J. Spatial socioeconomic data as a cost in systematic marine conservation planning. Conserv. Lett. 2, 206–215 (2009).

Araújo, M.B. Conflicting rationalities limit the uptake of spatial conservation prioritizations. Nat. Rev. Biodivers. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44358-025-00042-z.

The Seychelles Marine Spatial Plan: On the Leading Edge of Marine Conservation & Climate Change (SMSP, 2022).

Booth, M. & Brooks, C. M. Financing marine conservation from restructured debt: a case study of the Seychelles. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 899256 (2023).

SMSP. Seychelles Marine Spatial Plan Initiative. https://seymsp.com (2025).

Marine Spatial Plans for Gulf of Bothnia, Baltic Sea and Skagerrak/Kattegat. Proposal to the Government (Reg. No 3628-2019) (Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management, 2019).

Marine Spatial Plans for the Gulf of Bothnia, the Baltic Sea and the Skagerrak/Kattegat (Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management, 2023).

SwAM. Marine Spatial Planning. www.havochvatten.se/en/eu-and-international/marine-spatial-planning (2025).

Acknowledgements

C.F.S. acknowledges funding from the European Union (ERC-2023-StG, GA 101117443) and the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia—FCT (doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04292/2020, doi.org/10.54499/UIDP/04292/2020, doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0069/2020). Views and opinions expressed are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union nor the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.F.S., L.M.W., and T.A. conceptualised and developed the first draft of the manuscript. E.G., H.C,. and J.M.R commented on the initial draft and contributed to revised versions of the manuscript. J.M.R. created Figs. 1 and 2. All authors revised and agreed on the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

C.F.S. is an Editor-in-Chief (co), L.M.W. is an Associate Editor, and E.G. and H.C. are Guest Editors of npj Ocean Sustainability but were not involved in the peer-review process or decision-making for this manuscript. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Frazão Santos, C., Wedding, L.M., Agardy, T. et al. Marine spatial planning and marine protected area planning are not the same and both are key for sustainability in a changing ocean. npj Ocean Sustain 4, 23 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44183-025-00119-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44183-025-00119-4

This article is cited by

-

Identifying priority areas for marine protection in Europe to support fisheries

npj Ocean Sustainability (2025)

-

Projecting climate change impacts on the distribution of the most captured tuna species on Atlantic waters

Biodiversity and Conservation (2025)

-

Five key opportunities to enhance the effectiveness of area-based marine conservation

npj Ocean Sustainability (2025)