Abstract

Recently, we found adults who received digital bibliotherapy featuring lived-experience narratives related to suicidal thoughts and behaviors reported lower suicidal thoughts, mediated by increased social connectedness and optimism. This study aimed to identify characteristics of narratives associated with decreased suicidal thinking and increased social connectedness and optimism. 1532 users of a social media platform responded to surveys before and after reading narratives. Mixed-methods content analysis and clustered multidimensional scaling tested whether clusters that shared narrative characteristics were related to suicidal thoughts, social connectedness and optimism. We identified three narrative clusters: Cluster 1: “Encouraging Readers to Live,” Cluster 2: “Sharing Personal Stories,” and Cluster 3: “Detailed Accounts.” Clusters 2 and 3 were associated with greatest reduction in suicidal thoughts, Cluster 2 with the greatest increase in social connectedness, and Cluster 3 with the greatest increase in optimism. Results suggest the optimal narratives for reducing suicidal thoughts are personal, detailed accounts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Suicide is one of the most pressing public health issues with over 700,000 people dying by suicide around the world each year1. Despite this tremendous burden, few effective interventions exist to help people at risk for suicide2. Given the scope of this problem, it is particularly important to develop scalable interventions for suicide that are accessible, effective, and engaging3.

In the past decade, numerous new platforms have been developed to provide or promote therapeutic support for people at risk for suicide4. These include online support tools5,6 and smartphone apps7 shown to provide therapeutic benefits for people with suicidal thoughts. Many people experiencing mental health challenges related to suicide seek out support and advice online8,9. Digital tools may also help reach those who do not seek out traditional mental health care, such as those unable to attend in-person talk therapy10,11.

Social media, in particular, is an appealing domain for suicide prevention as it is easily accessible, relatively inexpensive, and scalable, reaching large populations12. People with mental health challenges, including suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STB), have been shown to use digital social media as a way of communicating with others and a means of seeking out information about their challenges9,13,14,15. For young people in particular, social media may provide an opportunity to discuss stigmatized topics more anonymously16,17.

However, media reports have suggested that social media use may be linked with increased risk of suicide deaths, with highly publicized examples like online threads about suicide methods, leading to fears about suicide contagion as a consequence of reading about suicide18. This, in turn, motivated the development of media guidelines around the world for reporting on suicide19,20,21,22. In Australia, the Chat Safe project worked with young people to develop guidelines for talking about suicide on social media23. These guidelines focus on deterring communication that could have adverse effects for people at risk for STB (e.g., avoiding explicit reporting about methods of death) with the goal of increasing safety, but no guidelines to our knowledge have promoted communication about experiences related to suicide that could help at-risk people.

Guidelines for writing about suicide also have been created for traditional media to reduce harmful messaging and increase quality reporting24,25,26, but these guidelines must adjust to keep up with the rise of social media use among all people, including for communication about suicide and related concerns14,27. In part, the lack of guidelines in this regard may be due to a relative dearth of research evaluating whether social media content can benefit people with STBs. Over the past century, scholars have theorized about the possible psychiatric benefits of reading others’ first-hand accounts of emotional struggles, often called narrative-based bibliotherapy28.

Bibliotherapy may be a promising intervention for suicidal thoughts29 and suicide attempts30. In the only randomized-controlled trial of narrative-based bibliotherapy for STB to date, we demonstrated that at-risk individuals who read first-hand accounts of experiences with and (in some cases) recovery from STBs on a social media platform reported reduced suicidal thoughts compared to those on a waitlist31. This effect was mediated by increased social connectedness (i.e., reduced loneliness) and increased optimism (i.e., reduced hopelessness). Loneliness and hopelessness are two of the most commonly-cited risk factors for suicidal thinking32,33, and these are shown to be targeted by other forms of narrative-based programs and bibliotherapy in prior work, as well29,34,35,36,37.

Further, studies have evaluated the “Papageno effect,” the notion that media portrayals of suicide may help reduce suicide risk when they also document possibility and process of recovery38,39, underscoring the notion that increasing hope through describing paths toward healing may be central to therapeutic suicide-related story telling. We must further identify which types of themes in online social media content about suicide is beneficial for at-risk individuals. Armed with this knowledge, policymakers, social media platforms, parents, and educators may be better positioned to appropriately filter and/or guide content about suicide posted online.

The purpose of this study was to identify which characteristics of online first-hand narratives about suicide are most strongly associated with reduced suicidal thinking, increased social connectedness, and increased optimism. To this end, we explored two qualitative research questions and tested two quantitative hypotheses. Our qualitative research questions were: What kind of content is included in first-hand narratives about suicide posted on a social media platform, and how frequently does this kind of content appear in a sample of popular narratives selected from this platform? Our first quantitative hypotheses was that reading suicide-related narratives would be associated with decreased suicidal thoughts, increased social connectedness, and increased optimism, as in our past randomized controlled trial. Our second quantitative hypothesis, exploratory in nature, was that clusters of narratives with different content characteristics would be differentially associated with reduced desire to die, increased social connectedness, and increased optimism.

Methods

Platform description and study overview

The Mighty (www.themighty.com) is an online social media platform dedicated to supporting people with medical and mental health concerns. Users of The Mighty share information in a variety of formats (e.g., posts, comments, likes, image/video sharing, etc.) to increase users’ knowledge, coping abilities, and feelings of social connectedness. One prominent feature of The Mighty is first-hand narrative content shared by users with lived experience of STBs, as well as related concerns. To understand how users of The Mighty engage with and relate to this type of STB content, the user experience team at The Mighty collected self-report data (described further below) from participants who read suicide-related narratives posted to the platform. Participants were recruited through “pop-up” advertisements posted on the 55 most-popular suicide-related narratives published on the platform. These advertisements asked users if they were interested in responding to a brief, anonymous survey before and after reading the story, noting that the information they provided could help other users who may be experiencing STB. After providing consent to participate, participants responded to a brief series of questions, read the story they selected, and then were asked questions again. Participants who did not provide consent for the study were able to continue on to read the article they had selected, but they received no surveys.

Moderation

A team of moderators at The Mighty monitor all user generated content, including suicide-related content. The Mighty’s approach to moderation includes two manual reviews within 24 h. Content is considered in violation if it contains features such as abusive language or language that may be unnecessarily triggering to vulnerable people. Such content is edited or removed. As a result, while content related to experiencing STBs is permitted on the platform, graphic images or descriptions of suicidal behavior and methods are likely to be edited or removed. Mention of methods of self-harm or suicide attempt and descriptions of suicidal behavior, however, are not explicitly banned, and are present in our sample of narratives, assuming they did not meet criteria for moderation as abusive, unnecessary, and potentially triggering.

Participants

Participants were a novel sample of n = 1535 users of The Mighty. Nineteen participants (1.2%) did not submit ratings of the outcomes of interest after they read the narrative. These participants were thus excluded from further analyses, leaving a final analysis sample of n = 1516. To understand motivation for seeking out online suicide-related narrative content, participants in this sample were asked to “select all that apply” in response to the question “What brought you to this story on The Mighty?” Sixty-four percent indicated they “had suicidal thoughts in the past,” 42% indicated they were “currently feeling suicidal,” 21.4% indicated they knew “someone who is/was suicidal,” 17.2% indicated they were “just curious to learn more about the topic,” 5.4% indicated they were “a medical/mental health professional who works with people who are suicidal,” 3.3% indicated they were “an educator with students who are/might be suicidal,” and 5.9% indicated they preferred “not to say.” Because our intent was to understand the impact of reading these narratives, all participants were included in analyses.

No demographic information for this study’s sample was collected. However, The Mighty had previously conducted a demographic survey distributed to the users who had subscribed to the ten most popular topics hosted on The Mighty, one of which was the topic ‘Depression,’’ which features many stories about suicidal thinking. Results from n = 1407 respondents suggested that 90% identified as White, 90% identified as Female, and 72% of users were between 35 and 64 years of age (the modal age group was 45–54 and accounted for 27% of the survey’s sample). The Mighty has approximately 150,000 daily users who accessed the platform’s content across web, app, and email. Google and Pinterest were the most common ways users accessed content (typically via links to TheMighty.com), accounting for over 40% of traffic. Around 20% of users accessed TheMighty.com directly.

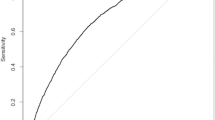

Procedures and measures

Participants responded to a brief 3-item survey before and after reading each article assessing the following constructs: suicidal thoughts, social connectedness, and optimism. Respectively, the survey items corresponding to each of these constructs were: “Right now, how much do you feel: (a) like you want to die?; (b) connected to other people (like you are not the only one with your problems)?; and (c) optimistic about your future (like your current concerns might get better)?” Participants responded to one additional survey item after reading each narrative: “how much do you feel like you can identify with the author of this story?” These items were presented in random order at each assessment point, and they were each rated using a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 10 (“definitely”). We intended these survey items to be clear and brief to reduce participant burden, maximize face validity, and increase the overall response rate. Distributions of the pre-narrative ratings of all three outcomes are displayed in Fig. 1 for those participants who reported that current suicidal thoughts motivated them to read the narrative (n = 646, 42.6%; top row) and those who did not report that current suicidal thoughts motivated them to read the narrative (n = 870, 57.4%; bottom row). At the conclusion of each suicide-related narrative, all participants were encouraged to contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline if they needed support.

Distributions in the top row (A, top left; B, top center; C, top right) are participants who reported that current suicidal thoughts motivated them to read the narrative. Distributions on the bottom row (D, bottom left; E, bottom center; F, bottom right) are participants who did not report that suicidal thoughts motivated them to read the narrative.

Data Acquisition

Data used for this study were collected by The Mighty for internal research purposes and were subsequently shared with the study team for further analyses. Preliminary results gleaned from these pilot data were used to inform the development of our randomized controlled trial, described elsewhere31. The data shared with the research team did not contain participant demographic identifiers beyond country of origin (inferred from IP addresses, which were used as individual participant identifiers). Nine IP addresses were associated with two or more pre/post ratings of the outcomes of interest. Only the first pre/post responses for each outcome of interest were analyzed for these participants; subsequent responses were excluded from analyses. Of note, results from our previous RCT indicated that reading more narratives was not associated with a greater treatment effect (i.e., we found no evidence of a dose-response effect31. The Harvard University Institutional Review Board (IRB19-0843) provided approval prior to data analysis.

Data analysis plan: qualitative analysis

We used content analysis to identify the qualitative characteristics included in each of the 43 most-popular suicide-related narratives. We chose the content analysis approach for its integration of qualitative analysis principles while allowing us to quantify the frequency that content was identified in each article40. We drew on the quantitative content analysis approach outlined by Krippendorrf41 and the methodology of Neuendorf42 to conceptualize the content of the narratives qualitatively, allowing us to interpret and describe the narratives while also calculating the frequency with which particular content is expressed as a percentage. All qualitative data were managed in NVivo (v. 11).

Content analysis began with one researcher (JS) reading and considering thematic content in a sub-selection of ten semi-randomly selected articles. A code book was then developed both inductively, based on characteristics identified within these articles, and deductively, by including specific codes of interest identified from the literature43. The process of code book development was an iterative, continuous process as is described by44. The codebook was refined and shaped with input of two additional researchers (PF, DM) to improve construct validity and ensure multiple perspectives were considered. Codes were non-exclusive, in that the same portion of each narrative could be coded at any number of codes, resulting in very rich data regarding the content of each article. Sub-codes and parent codes were organized to support the coding process and coder decision-making as they read and interpreted a text. For example, a coder could first identify that the author is describing help-seeking, then whether they specify the nature of this help-seeking, and finally if this experience was considered helpful or unhelpful.

A team of four trained research assistants, divided into two teams of two, and one auditor (JS) coded 43 articles included in the initial analysis, including those with fewer than ten survey responders, which were subsequently excluded from quantitative analyses, as described below. Each pair of research assistants coded 75% of all articles, with 50% crossover between pairs. Coding was discussed within and between pairs and with the wider team to review consistency, refine the code book, and discuss significant discrepancies. Consensus coding was not used in cases of disagreement; discrepant codes were included to allow for the possibility that readers may understand and interpret content differently on the basis of their experiences, culture, and backgrounds. Cohen’s kappa was selected to measure inter-rater reliability given features of the code book, analytic plan, and text sample. Each narrative was coded by a pair of coders and a test statistic was needed that is well-suited to assessing inter-rater reliability in content analysis which involves interpreting rhetorical texts, such as diary entries and prose, which Cohen’s kappa may be particularly well suited for45. Across the final 77 codes inter-rater reliability was fair to excellent with a Kappa coefficient range of 0.61–0.99 (M = 0.81, SD = 0.13, Mode = 0.77). Some codes were refined throughout the coding process to improve reliability (e.g., elaborating definitions and finding additional examples). No codes were dropped due to low reliability. Coders reported that some narratives were simpler to code and produced greater agreement between coders, particularly those shorter in length, whereas other narratives were more complex and resulted in greater discrepancy between coders, particularly longer articles. The complete codebook is available to researchers on request.

Illustrative examples of each code were identified by JS and extracted to qualitatively exemplify the kind of content described by each code. NVivo software was utilized to identify the percentage of content within each story included at each code. Descriptive statistics, including mean, range, and standard deviation, were calculated for each code for the purposes of illustrating the richness of the narratives including the frequency with which codes occurred and the range across stories. After reviewing qualitative analysis, qualitative descriptions and names for each cluster were developed.

Data analysis plan: narrative cluster identification

To ensure that each narrative had a sufficient number of responses to the three assessments to permit statistical analysis, we excluded 25 articles that contained fewer than ten participant pre/post responses, leaving a final set of 19 articles for quantitative analysis. The vast majority of the sample (1507 participants, 99.41%) responded to survey items for a single narrative only. For the nine participants (0.59%) who responded to survey items for more than one narrative, we analyzed only the first submitted set of pre- and post-narrative responses.

Next, we analyzed the full set of subcategory content codes for those 19 articles with the goal of understanding how different types of articles were associated with the outcomes of interest (suicidal thoughts, social connectedness, and optimism). Due to the highly complex nature of the content code subcategories (77 different ratings for each article), we used ratio multidimensional scaling (MDS46,47; as implemented in the R package “smacof”48,49. The Stress-1 value for our model was 0.21. MDS, a close relative of principal components analysis, is a dimension reduction technique that represents proximities (i.e., correlations) among objects as distances among points in a low-dimensional space (with given dimensionality). It allows the exploration of similarity structures in a multivariate data set, and provides a “map” of the data that can be interpreted intuitively. In this study, we explored similarities among the 19 articles using metric MDS, plotted in a two-dimensional space.

Using the hclust() function, we applied the Ward2 hierarchical clustering algorithm to the fitted MDS similarity solution50,51. In conjunction with selection based on intuitive interpretability, we identified the optimal number of clusters using the R package “NbClust”52, which determined that three clusters provided the most reliable solution, according to the majority rule53. Finally, we assigned each article a nominal value corresponding to its respective cluster membership (1, 2, or 3).

Data analysis plan: quantitative analysis

We used paired-samples t-tests to evaluate whether participants reported lower suicidal thoughts, higher social connectedness, and higher optimism after reading the narratives than before reading the narratives (quantitative hypothesis 1). We performed these paired-samples t-tests across the full set of narratives, and then separately for narratives belonging to Clusters 1, 2, and 3. To identify individual differences in the users’ responses to these narratives, we divided the sample based on participant characteristics and compared outcomes before and after reading the narratives (see Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 for results of subgroup analysis).

We then used ANCOVA to evaluate whether the different narrative clusters were associated with differences in participants’ rating of suicidal thoughts, social connectedness, and optimism after reading the articles (quantitative hypothesis 2). In each of these three ANCOVAs, we modeled a single post-narrative outcome of interest as a function of cluster membership, controlling for the corresponding pre-narrative rating of the outcome. We used dummy coding for the nominal variable, cluster membership, in each of these models, with cluster 3 set as the reference category.

We used ANOVA to test whether post-narrative ratings of identification with authors of the narratives differed between the three narrative clusters.

Results

Content analysis

Seventy-seven codes were included in the final analysis. The eight core codes and the mean percentage of content included at these codes per narrative are displayed in Table 1, alongside sub-codes and an example quote from a narrative illustrating typical content within each code.

Clustering

Results of our clustered multidimensional scaling analysis indicated that narratives comprised three distinct clusters. The similarities among the narratives, which are each color-coded according to cluster membership, are displayed in Fig. 2.

A(left panel) shows a dendrogram illustrating hierarchical relationships between the suicide narratives based on each of the 77 qualitative codes. The different narratives are represented on the horizontal axis, each with a separate letter indicator. The vertical axis, height, represents Euclidean distance, a measure of multidimensional similarity between the narratives. Narratives connected at greater heights are more dissimilar than narratives connected at lower heights. Each of the three clusters is indicated with a colored box. The color of the indicator boxes and each narrative point in the figure corresponds to the narrative’s cluster membership. B(right panel) shows a configuration plot illustrating the similarities between the narratives, based on the 77 subcategory codes, in two-dimensional space. The two-dimensional distance between any pair of narratives is equivalent to the Euclidean distance between those narratives. Narratives appearing closer together are more similar than narratives that are farther apart. The mean qualitative content of each cluster by code is depicted in Fig. 2.

Illustrations of each cluster’s mean percentage of content codes can be found in Fig. 3. Descriptively, Cluster 1 narratives (Encouraging Readers to Live) featured a substantially higher proportion of Reasons for Living, Directly Addresses Reader, and Expresses Understanding content codes. Cluster 1 narratives also included a marginally higher proportion of Help-Seeking codes and relatively limited references to STB and Mental Illness.

Cluster 2 narratives (Sharing Personal Stories) were substantially higher than the other clusters in the use of personal stories. In other words, these authors tended to share their own lived experiences with STBs and distress through anecdotes and accounts of experiences within their lives (e.g., an author describing a day in their life and how suicide-related experiences impact them). Cluster 2 narratives had the lowest proportion of Expresses Understanding codes, included proportionately greater Reasons for Living than Reasons for Dying codes, and moderate references to Help Seeking and STBs.

Cluster 3 narratives (Detailing Accounts of STB) had a substantially higher proportion of references to STBs (e.g., an author describing the content of their suicidal thoughts), and a substantially lower proportion of Personal Story codes, relative to narratives in Clusters 1 and 2. In Cluster 3 narratives, Reasons for Living codes were relatively equivalent to Reasons for Suicide codes. Cluster 3 narratives also contained moderate references to Help-Seeking and Mental Illness.

Change in outcomes after reading narratives

Overall (collapsing across the three narrative clusters and all participants), we found that participant ratings of all three outcomes of interest improved after reading STB narratives (Table 2). Across all narratives and all participants improvements in suicidal thoughts were associated with improvements in connectedness (r = −0.15, p < .001) and optimism (r = −0.21, p < .001).

Specifically for Cluster 1 narratives, we found that participant ratings of suicidal thoughts did not change significantly, but social connectedness and optimism each improved after reading the narratives (Table 2). Among Cluster 1 narratives, improvements in suicidal thoughts were associated with improvements in connectedness (r = -0.19, p = 0.004) and optimism (r = −0.34, p < 0.001).

For Cluster 2 narratives, we found that participant ratings of all three outcomes improved after reading the narratives (Table 2). Among Cluster 2 narratives, improvements in suicidal thoughts were associated with improvements in connectedness (r = −0.14, p < 0.001) and optimism (r = −0.15, p < 0.001).

For Cluster 3 narratives, we found that participant ratings of all three outcomes improved after reading the narratives (Table 2). Among Cluster 3 narratives, improvements in suicidal thoughts were associated with improvements in connectedness (r = −0.21, p = 0.020) and optimism (r = −0.36, p < 0.001).

Next, to evaluate the possibility of different benefits across subgroups of participants, we examined pre/post changes in outcomes across groups of participants with differing pre-narrative characteristics: 1325 participants (87.5%) who reported some suicidal thoughts (≥1 on “desire to die”), 191 participants (12.6%) who reported no suicidal thoughts (0 on “desire to die”), 646 participants (42.6%) who reported current suicidal thoughts as a motivator for finding the narrative, and 870 participants (57.4%) who did not report current suicidal thoughts as a motivator for finding the narrative. Results of these subgroup analyses (Supplemental Table 1) largely mirrored those of the entire sample (Table 2), with three noteworthy distinctions: participants who reported no baseline suicidal thoughts experienced a small increase in suicidal thoughts after reading narratives from Cluster 2 (d = 0.22) and no change in connectedness or optimism after reading narratives from Cluster 1.

We also identified that 454 participants (29.95%) reported decreases in suicidal thoughts, 224 participants (14.78%) reported increases in suicidal thoughts, and 838 participants (55.28%) reported no change in suicidal thoughts. Comparing benefits across these three subgroups, we found that those with decreases in suicidal thoughts reported the largest absolute change in suicidal thoughts (d = −1.33) and the greatest increase in connectedness (d = 0.57) and optimism (d = 0.43). Although those with increases in suicidal thoughts reported a large increase in suicidal thoughts on average (d = 1.26), they also reported increases in connectedness (d = 0.23) and optimism (d = 0.15). Those with no change in suicidal thoughts included the greatest proportion of participants who reported no pre-narrative suicide thoughts (19.44%), and they had the highest correlation between post-narrative suicidal thoughts and connectedness (r = −0.45) and between post-narrative suicidal thoughts and optimism (r = −0.65). These three subgroups did not differ substantially in other ways. Further details on these subgroup comparisons can be found in Supplemental Table 2.

Comparison of outcomes between clusters

To more directly compare the benefits of narratives from the three clusters, we evaluated associations between cluster membership and T2 ratings of suicidal thoughts, social connectedness, and optimism (Table 3). Participants rated their suicidal thoughts as lower after reading narratives in Clusters 2 and 3, relative to narratives in Cluster 1 (see note following Table 3 for further detail about pairwise comparisons). Participants rated their social connectedness as higher after reading narratives in Cluster 2, relative to narratives in Cluster 3. Participants rated their optimism as higher after reading narratives in Cluster 3, relative to narratives in Cluster 1. No other comparisons were significantly different from one another.

Finally, relative to narratives in Cluster 3, participants reported higher feelings of being able to identify with the authors of narratives from Cluster 1 (ß = 0.51, CI: 0.29, 0.74, p < 0.001) and Cluster 2 (ß = 0.53, CI: 0.35, 0.72, p < 0.001).

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to understand which characteristics of first-hand narratives about STBs are most helpful for the mental health of readers. Our recent work showed that reading these types of narratives benefits people at risk for suicide31, but no prior work has systematically explored how specific types of content contained within suicide narratives (i.e., narrative characteristics) can help at-risk individuals. To fill this gap in our knowledge, we used a mixed-method design to analyze the content of suicide-related narratives, identify clusters of narratives based on similar content, and test whether readers’ suicide risk improved after reading narratives from each of the three clusters. Our primary results suggested that after reading the narratives, participants on average reported improvements in the three outcomes of this study: suicidal thoughts, social connectedness, and optimism. We further found that clusters of narratives with similar characteristics were uniquely associated with improvements in the measured outcomes. We provide further commentary on each result below.

Despite the differential benefits of the three clusters, the narratives comprising these clusters were associated with improvements in each of the three outcomes at the group level (except for Cluster 1, for which readers reported a non-significant reduction in suicidal thoughts). Given that these narratives were selected from the most popular suicide-related content on a highly moderated social media platform intended to help people who are struggling, this result matched our expectations.

We did, however, identify that a proportion of participants (~1 in 6.5) reported higher suicidal thoughts after reading the narratives. It is possible that for some of the participants, reading suicide-related narratives increased suicidal ideation. These participants did not read different narrative clusters than participants who reported decreases or no change in suicidal thoughts, suggesting that increases in suicidal thoughts were not associated with reading narratives from one particular cluster. These results reflect a core issue in suicide prevention research and intervention design: what works for one person may not work for another. In the case of communicating about suicide, while this may be beneficial for some people, it is not for all. We must remain mindful of balancing the potential benefits of bibliotherapy for suicide prevention with its potential harms. An alternative explanation is that we have no knowledge about their suicidal thoughts outside of the periods immediately before and after reading the narrative. Given that the intensity of suicidal thoughts varies naturally across periods as brief as 10 min54, it is possible that participants may have been experiencing increases in suicidal thoughts prior to reading the narrative, and the narrative could have had no effect on or even helped to stabilize this increase. Interestingly, these participants who reported increases in suicidal thoughts also reported improvements in both connectedness and optimism, on average, suggesting they may have derived some benefit from the narratives. It is possible that for some participants anti-suicidal benefits lag behind improvements in mechanisms that support reductions in suicidal thoughts, like social connectedness and optimism31. Further research is needed to clarify the contexts in which and the people for whom supportive STB narratives are most likely to provide anti-suicidal benefits, as well as improve our understanding of the people who may not be benefit or whose suicidal ideation may increase. One especially important consideration in this regard is the exact time course over which these narratives influence suicidal thoughts. Other important considerations that we did not measure are participants’ familiarity with others’ STB narratives, perceived accessibility of suggested strategies for improvement, mental health conditions, and affective state at the time of reading the narratives. Each of these factors could influence the impact of STB narratives on the reader, and are topics for exploration in future research.

Nevertheless, these findings also offer further evidence that supportive digital communities can benefit the mental health of people who may be at risk for suicide, consistent with results from our prior clinical trial31. In addition, reductions in suicidal thoughts were associated with increases in social connectedness and optimism across the entire set of narratives and for each cluster individually. This finding provides support, in line with our prior work, that social connectedness and optimism are possible mechanisms of change for suicidal thoughts that can be targeted by digital narrative communication. Although the effect sizes we reported for the entire sample are small, even modest effects can translate to societal benefits when applied at scale55,56. This possibility is especially likely given that this bibliotherapy is brief and low-burden, features that are important in suicide prevention where scalable interventions are needed3.

Considering the differential benefits of narratives from the three clusters, we found that participants reported the greatest reduction in suicidal thoughts after reading Cluster 2 narratives, which featured personal experiences with STB, and Cluster 3 narratives, which featured a relatively high degree of detail about these experiences. Although there are concerns about suicide contagion via digital social media12,18,57, our results demonstrate that in some contexts, sharing personal details about experiences related to STB can benefit readers at risk for suicide. In fact, narratives from Clusters 2 and 3 included more explicit references to STB than those from Cluster 1, suggesting that sharing such details in a supportive context (e.g., alongside strategies for help-seeking, which were common in Clusters 2 and 3) can benefit others with similar concerns.

Given that Cluster 1 narratives were associated with a smaller reduction in suicidal thoughts than the other two clusters, it may be tempting to conclude that Cluster 1’s defining characteristics (e.g., directly addressing the reader, expressing understanding, and discussing reasons for living) should be avoided in online suicide-related narrative sharing. However, these characteristics were present in Clusters 2 and 3, though to a somewhat lesser degree. One possible explanation for the lower suicidal benefit of Cluster 1 narratives is that these were experienced as more prescriptive, which can result in feelings of invalidation58 that might increase risk for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors59,60,61. Future research should investigate whether prescriptive aspects of online communication about suicide are experienced by the reader as more invalidating and less helpful. Nevertheless, our results suggest that optimal characteristics for buffering against suicide risk are personal, detailed narratives (which defined Clusters 2 and 3, respectively) that directly address the reader, express understanding, and discuss reasons for living.

We also found that participants rated their social connectedness (i.e., feeling less alone in one’s struggles) as highest after reading Cluster 2 narratives, which prominently featured personal, first-hand lived experiences. These narratives in Cluster 2 typically featured details about the authors’ past and current STB, including the content of suicidal thoughts and the authors’ motivations for thinking about suicide. Our prior work suggests that increasing social connectedness is a key mechanism supporting the buffering effects of reading these suicide-related narratives31. Thus, the present study extends our prior work by underscoring that the sharing of first-hand narrative details specifically may help readers feel more connected to the experiences of others, consistent with prior research on narrative therapy29,34,35,36,37. Further, communicating about first-hand struggles likely showcases transparency and authenticity, which are shown to support social connectedness in therapeutic contexts62,63,64. In line with this view, participants were most able to identify with the authors of narratives from Cluster 2 (alongside narratives from Cluster 1: Encouraging readers to live), providing further evidence that reading others’ personal narrative details related to STB can help reduce loneliness, a top risk factor for suicide65.

Our next result indicated that participants reported the greatest increase in optimism after reading Cluster 3 narratives, which tended to discuss experiences with STB in a high degree of detail. We were somewhat surprised that Cluster 1 narratives, which contained higher references to reasons for living and help seeking, were associated with lower subsequent optimism than Cluster 3 narratives. It is possible that readers may have felt more optimistic after reading Cluster 3 narratives because their authors offered details of their challenges and chose to persist with life, potentially providing readers with a sense for the magnitude of challenges that can be overcome. Future research can evaluate this possibility directly by comparing the benefits of reading narratives with similarly prevalent reasons for living and help seeing, but with varying degrees of detail offered. Another possibility is that Cluster 3 narratives induced greater downward social comparison (i.e., perceiving the author as “worse off” than themselves), related to less prevalent reasons for living and marginally more prevalent reasons for dying. Downward social comparison is used to support distress tolerance in Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), an evidence-supported treatment for STBs66, though evidence on the efficacy of social comparison is mixed67. Nevertheless, downward social comparisons may have helped participants perceive their own concerns as less dire, increasing their feelings of optimism, an effect that has been demonstrated in prior work68,69. This may be a fruitful area for future research, given the motivation to reduce the negative consequences of social comparisons via social media, especially among adolescents70.

Because we did not ask respondents to identify their demographic information, we are unsure of who, exactly, responded to the study’s surveys. Based on past demographic surveys of this site’s readership, it is likely that participants were predominantly women, identifying as white, in middle adulthood. Further research is needed to explore both the generalizability of these findings across groups, and whether content differentially impacts suicidal ideation based on population characteristics. For instance, without demographic information we are unable to measure whether social connectedness relates solely to the content of narratives or is also influenced by sharing identities such as gender or race with the author. Given our limited knowledge of the sample and their experience reading the narratives, we also cannot conclude on the basis of this pilot why content of this kind may have increased optimism and reduced suicidal ideation. Additionally, understanding the characteristics of those who access sites like The Mighty or other popular media platforms may help identify specific phenotypes of characteristic, mechanism, and response to suicide related narratives, critical to understanding how, for whom, and when these may serve as effective interventions. Without demographic characteristics from this sample, the degree to which we can generalize these findings to users of other social media platforms is limited. We also are not able to explore if there may be characteristics of a reader that contribute to their decision to click on a particular story, and it is possible that different readers will select different stories. For example, Cluster 3 readers tended to have higher baseline suicidal ideation. Understanding the characteristics of readers would allow us to explore decision making in viewing certain content and how this may influence outcomes.

Next, the team of trained coders who provided ratings of each narrative’s qualitative dimensions may not have had lived experience with STB. This limitation highlights the nuance of language and its contextual interpretation, as well as the importance of consulting with stakeholders to understand how particular content impacts them directly. The voices and expertise of those with lived experience of suicidality should be included in all intervention designs71 especially in regard to digital and social media based intervention.

Additionally, narratives used for this study were selected from a site with the explicit goal of helping people who are struggling. As such, all narrative content we used in this study was moderated with this goal in mind. Our results therefore may not generalize to other less well-moderated social media platforms.

Finally, most major codes were present in all clusters – with the exception of Expressing Understanding codes. Variation in the kind of content and overall narrative ‘type’ was generally observed not from the presence of each code, but the frequency of its presence, as illustrated in Fig. 2. This highlights an important challenge for digital platforms that may host content related to STBs. Namely, identifying narratives that are more likely to be associated with positive change for readers is a complex task, and simple solutions (such as banning any reference to specific methods, as is common in traditional media) are unlikely to be effective. More sophisticated methods of reviewing content at scale are essential to meet this challenge.

This study provides further support that narrative-based bibliotherapy can be an effective, low-burden intervention for suicide risk. This study also helps us understand which thematic components of suicide-related narratives may be most beneficial for reducing suicide risk in others. For many people, access to mental healthcare is limited. This is due to a variety of factors such as the low supply of providers, limited flexibility in work, financial burdensomeness of mental healthcare, competing family obligations (e.g., childcare), stigma, or a combination of these factors72. In marginalized communities, these concerns may be especially prevalent73,74. Narrative-based bibliotherapy, consisting of reading narratives like those featured in this study, can provide a needed resource to support mental health in these communities. Moreover, narrative-based therapy can be a more democratized intervention than traditional mental healthcare, which relies on the expertise of highly educated professionals who have benefitted from privilege. By leveraging lived experience with psychological challenges, narrative-based bibliotherapy can speak to the needs of marginalized people, helping them feel more supported and less isolated. One future direction, therefore, is to adapt narrative-based bibliotherapy to support people from marginalized communities by collecting, studying, and sharing the first-hand STB narratives of people from diverse cultural and sociodemographic backgrounds. Another related future direction is to evaluate whether narrative-based bibliotherapy can help with other stigmatized conditions, such as challenges with substance use. A final future direction is to test whether narrative-based bibliotherapy can provide a stabilizing resource in contexts where treatment providers are unavailable or as a bridge to treatment for people who are on waiting lists for traditional mental healthcare services.

This study has implications for intervention design demonstrating that user-generated narratives about STBs, particularly those containing balanced accounts of suicidality and first-hand stories, show promise as a scalable intervention for suicidal ideation. Additionally, the findings of this study have significant implications for social media networks and other digital platforms. Platforms which host user generated content frequently implement community posting guidelines related to content which include references to STBs. For example, platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Reddit encourage users to report posts related to STBs and state they will contact users posting such content with helpful information or crisis resources. However, existing guidelines often contain no references to posting helpfully about suicide on their platforms. This is an important gap that our study helps start to fill. Providing users advice about how to post suicide related content that could be beneficial to readers can promote agency and empowerment. Such guidelines could also be beneficial to content evaluators facing the challenges of determining what content to block, de-platform, hide behind trigger warnings, or stop promoting. Importantly, banning content related to suicide or which references an author’s own suicide narrative or suicidal thoughts and behavior would have excluded the majority of narratives included in this study.

User-generated digital content shows potential as an effective, scalable suicide intervention. Our findings indicate that the type of content has important implications for predicting the experience of reading narratives about suicide posted online. In particular, content that increases a readers’ social connectedness, possibly through sharing personal stories, and content that increases a sense of optimism, likely through offering balanced, nuanced, and hopeful stories, is particularly likely to be associated with reduced suicidal thoughts. Social media and digital companies should be encouraged to consider their policies regarding posting about suicide on their platforms. Authors of digital content can be empowered to know that sharing their stories of resilience, hope, and recovery can meaningfully impact others in their community.

Data availability

Data are available to qualified researchers upon request.

Code availability

Code is available to qualified researchers upon request.

References

World Health Organisation. Suicide. (WHO, 2021).

O’Connor, R. C. & Portzky, G. Looking to the future: a synthesis of new developments and challenges in suicide research and prevention [Perspective]. Front. Psychol. 9, 2139 (2018).

Kreuze, E. et al. Technology-enhanced suicide prevention interventions: a systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare 23, 605–617 (2017).

Torok, M. et al. Suicide prevention using self-guided digital interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Digital Health 2, e25–e36 (2020).

Jaroszewski, A. A.-O., Morris, R. R. & Nock, M. K. Randomized controlled trial of an online machine learning-driven risk assessment and intervention platform for increasing the use of crisis services. J. Consulting Clin. Psychol. 87, 370–379 (2019).

Jiang, M., Ammerman, B. A., Zeng, Q., Jacobucci, R. & Brodersen, A. Phrase-level pairwise topic modeling to uncover helpful peer responses to online suicidal crises. Humanities Soc. Sci. Commun. 7, 36 (2020).

Franklin, J. C. et al. A brief mobile app reduces nonsuicidal and suicidal self-injury: evidence from three randomized controlled trials. J. Consulting Clin. Psychol. 84, 544–557 (2016).

Berry, N. A.-O. et al. #WhyWeTweetMH: understanding why people use Twitter to discuss mental health problems. J. Med. Internet Res. 19, e107 (2017).

Mitchell, K. J. & Ybarra, M. L. Online behavior of youth who engage in self-harm provides clues for preventive intervention. Preventive Med. 45, 392–396 (2007).

Perrin, P. A.-O. X., Pierce, B. S. & Elliott, T. R. COVID-19 and telemedicine: a revolution in healthcare delivery is at hand. Health Sci. Rep. 3, e166 (2020).

Yuen, E. K., Goetter, E. M., Herbert, J. D. & Forman, E. M. Challenges and opportunities in internet-mediated telemental health. Professional Psychol.: Res. Pract. 43, 1–8 (2012).

Robinson, J. et al. Social media and suicide prevention: a systematic review. Early Intervention Psychiatry 10, 103–121 (2016).

Eichenberg, C. Internet message boards for suicidal people: a typology of users. CyberPsychology Behav. 11, 107–113 (2008).

Franz, P. J., Nook, E. C., Mair, P. & Nock, M. K. Using topic modeling to detect and describe self-injurious and related content on a large-scale digital platform. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 50, 5–18 (2020).

Niederkrotenthaler, T., Gould, M., Sonneck, G., Stack, S. & Till, B. Predictors of psychological improvement on non-professional suicide message boards: content analysis. Psychological Med. 46, 3429–3442 (2016).

Gibson, K., Wilson, J., Grice, J. L. & Seymour, F. Resisting the silence: The impact of digital communication on young people’s talk about suicide. Youth Soc. 51, 1011–1030 (2017).

Weinstein, E. et al. Positive and negative uses of social media among adolescents hospitalized for suicidal behavior. J. Adolesc. 87, 63–73 (2021).

Pirkis, J., Blood, W., Sutherland, G. & Currier, D. Suicide and the news and information media: a critical review. (Everymind, 2018).

Everymind. Reporting suicide and mental ill-health: a mindframe resource for media professionals., (Mindframe, 2020).

Pirkis, J. et al. Media guidelines on the reporting of suicide. Crisis 27, 82–87 (2006).

Reporting on Suicide. Best practices and recommendations for reporting on suicide. https://reportingonsuicide.org/recommendations/ (2020).

World Health Organisation. Preventing suicide: a resource for media professionals, update 2017. (World Health Organisation, 2017).

La Sala, L. et al. Can a social media intervention improve online communication about suicide? A feasibility study examining the acceptability and potential impact of the #chatsafe campaign. PLoS ONE 16, e0253278 (2021).

Bohanna, I. & Wang, X. Media guidelines for the responsible reporting of suicide: a review of effectiveness. Crisis 33, 190–198 (2012).

Pirkis, J. et al. Changes in media reporting of suicide in Australia between 2000/01 and 2006/07. Crisis 30, 25–33 (2009).

Gould, M. S. Suicide and the media. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 932, 200–224 (2001).

Maloney, J. et al. How to adjust media recommendations on reporting suicidal behavior to new media developments. Arch. Suicide Res. 18, 156–169 (2014).

Aiex, N. K. Bibliotherapy. Vol. Report NO. EDO-CS-93-05 (Indiana University, 1993).

Akhouri, D. Bibliotherapy as a self management method to treat mild to moderate level of depression. Int. J. Res. Soc. Sci. 8, 2249–2496 (2018).

Evans, K. et al. Manual-assisted cognitive-behaviour therapy (MACT): a randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention with bibliotherapy in the treatment of recurrent deliberate self-harm. Psychol. Med. 29, 19–25 (1999).

Franz, P. J. et al. Digital bibliotherapy as a scalable intervention for suicidal thoughts: A randomized controlled trial. J. Consul. Clin. Psychol. 90, 626–637 (2022).

McClelland, H., Evans, J. J., Nowland, R., Ferguson, E. & O’Connor, R. C. Loneliness as a predictor of suicidal ideation and behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J. Affect. Disord. 274, 880–896 (2020).

Ribeiro, J. D., Huang, X., Fox, K. R. & Franklin, J. C. Depression and hopelessness as risk factors for suicide ideation, attempts and death: meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Br. J. Psychiatry 212, 279–286 (2018).

Berkley-Patton, J. et al. Adapting effective narrative-based HIV-prevention interventions to increase minorities’ engagement in HIV/AIDS services. Health Commun. 24, 199–209 (2009).

Gualano, M. R. et al. The long-term effects of bibliotherapy in depression treatment: Systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 58, 49–58 (2017).

Llewellyn-Beardsley, J. et al. Characteristics of mental health recovery narratives: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. PLoS ONE 14, e0214678 (2019).

Monroy-Fraustro, D. et al. Bibliotherapy as a non-pharmaceutical intervention to enhance mental health in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods systematic review and bioethical meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 9, 629872 (2021).

Lueck, J. A. & Poe, M. Werther or Papageno? Examining the effects of news reports of celebrity suicide versus non-celebrity peer suicide on intentions to seek help among vulnerable young adults. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 53, 1038–1054, (2023).

Niederkrotenthaler, T. et al. Role of media reports in completed and prevented suicide: Werther v. Papageno effects. Br. J. Psychiatry 197, 234–243 (2010).

Bengtsson, M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open 2, 8–14 (2016).

Krippendorff, K. COntent Analysis: An Introduction To Its Methodology. (Sage Publications, 2018).

Neuendorf, K. A. The Content Analysis Guidebook. (Sage Publications, 2017).

Bauer, M. W. in Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound (eds Martin W. B. & G. Gaskell) (SAGE Publications, 2000).

Erlingsson, C. & Brysiewicz, P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 7, 93–99 (2017).

Oleinik, A., Popova, I., Kirdina, S. & Shatalova, T. On the choice of measures of reliability and validity in the content-analysis of texts. Qual. Quant. 48, 2703–2718 (2014).

Borg, I. & Groenen, P. J. F. Modern Multidimensional Scaling. 2nd Ed. edn, (Springer, 2005).

Kruskal, J. B. Multidimensional scaling by optimizing goodness of fit to a nonmetric hypothesis. Psychometrika 29, 1–27 (1964).

Leeuw, J. D. & Mair, P. Multidimensional scaling using majorization: SMACOF in R. J. Stat. Softw. 31, 1–30 (2009).

Mair, P., Groenen, P. J. F. & Leeuw, J. D. More on multidimensional scaling and unfolding in R: smacof version 2. J. Stat. Softw. 102, 1–47 (2022).

Kruskal, J. B. In Classification and Clustering (ed J. Van Ryzin) 17–44 (Academic Press, 1977).

Murtagh, F. & Legendre, P. Ward’s hierarchical agglomerative clustering method: which algorithms implement ward’s criterion? J. Classif. 31, 274–295 (2014).

Charrad, M., Ghazzali, N., Boiteau, V. & Niknafs, A. NbClust: an R package for determining the relevant number of clusters in a data set. J. Stat. Softw. 61, 1–36 (2014).

Prieto, M. et al. Data-driven classification of the certainty of scholarly assertions. PeerJ. 8, e8871 (2020).

Coppersmith, D. D. et al. Mapping the timescale of suicidal thinking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2215434120 (2023).

Carey, E. G., Ridler, I., Ford, T. J. & Stringaris, A. Editorial Perspective: when is a ‘small effect’ actually large and impactful?. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 64, 1643–1647 (2023).

Funder, D. C. & Ozer, D. J. Evaluating effect size in psychological research: sense and nonsense. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2, 156–168 (2019).

Swedo, E. A. et al. Associations between social media and suicidal behaviors during a youth suicide cluster in Ohio. J. Adolesc. Health 68, 308–316 (2021).

Ramaiya, M. et al. Competency of primary care providers to assess and manage suicide risk in Nepal: The role of emotional validation and invalidation techniques. SSM - Ment. Health 4, 100229 (2023).

Adrian, M. et al. Parental validation and invalidation predict adolescent self-harm. Professional Psychol. Res. Pract. 49, 274–281 (2018).

Linehan, M. M. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment Of Borderline Personality Disorder. (Guilford Publications., 1993).

Yen, S. et al. Perceived family and peer invalidation as predictors of adolescent suicidal behaviors and self-mutilation. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 25, 124–130 (2015).

Glickman, K., Katherine Shear, M. & Wall, M. M. Therapeutic alliance and outcome in complicated grief treatment. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 11, 222–233 (2018).

Langhoff, C., Baer, T., Zubraegel, D. & Linden, M. Therapist–patient alliance, patient–therapist alliance, mutual therapeutic alliance, therapist–patient concordance, and outcome of CBT in GAD. J. Cogn. Psychother. 22, 68–79 (2008).

Zur, O., Williams, M. H., Lehavot, K. & Knapp, S. Psychotherapist self-disclosure and transparency in the Internet age. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 40, 22–30 (2009).

Franklin, J. C. et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 143, 187–232 (2017).

Linehan, M. M. DBT® skills training manual, 2nd ed. (Guilford Press, 2015).

Richmond, J. R., Edmonds, K. A., Rose, J. P. & Gratz, K. L. Experimental investigation of social comparison as an emotion regulation strategy among young women with a range of borderline personality disorder symptoms. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 44, 1077–1089 (2022).

Brown, S. L. & Imber, A. The effect of reducing opportunities for downward comparison on comparative optimism. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 33, 1058–1068 (2003).

Park, S. Y. & Baek, Y. M. Two faces of social comparison on Facebook: the interplay between social comparison orientation, emotions, and psychological well-being. Comp. Hum. Behav. 79, 83–93 (2018).

Nesi, J. & Prinstein, M. J. Using social media for social comparison and feedback-seeking: Gender and popularity moderate associations with depressive symptoms. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 43, 1427–1438 (2015).

Watling, D., Preece, M., Hawgood, J., Bloomfield, S. & Kõlves, K. Developing an intervention for suicide prevention: A rapid review of lived experience involvement. Arch. Suicide Res. 26, 465–480 (2022).

Andrade, L. H. et al. Barriers to mental health treatment: results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Psychol. Med. 44, 1303–1317 (2014).

Brown, K. et al. How can mobile applications support suicide prevention gatekeepers in Australian Indigenous communities? Soc. Sci. Med. 258, 113015 (2020).

Wexler, L. et al. Advancing suicide prevention research with rural American Indian and Alaska Native populations. Am. J. Public Health 105, 891–899 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge our research assistants who contributed to analysis on this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Co-first authors (J.S. and P.F.) drafted the original manuscript. Authors 1–3 (J.S. and P.F., D.M., A.J.), 5 (D.K.) and 11 (M.N.) contributed to conceptualization and design of the study. Authors 1 (J.S. and P.F.) and author 4 (P.M.) contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. Authors 6–10 (S.R., V.C.S., S.B., S.S., D.G., M.P.) contributed to the study conceptualization, design, and data acquisition. All authors reviewed and provided revisions on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Sara Ray, Vy Cao-Silveira, Savannah Bachman, Sarah Schuster, Daniel Grupensparger, and Mike Porath were employees of The Mighty when this study was conducted.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stubbing, J., Franz, P.J., Mou, D. et al. Identifying therapeutic characteristics of digital social media narratives about suicide: a mixed methods investigation. npj Mental Health Res 4, 41 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-025-00155-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-025-00155-5

This article is cited by

-

A Novel Hashtag Density Method for Identifying Suicide and Self-Harm Content on TikTok

Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science (2026)