Abstract

Deoxygenation in aquatic ecosystems threatens biodiversity at all levels of functional and genetic diversity. Recent studies have shown the prevalence of microorganisms that transform mercury into neurotoxic methylmercury (mercury methylators—hgcA+ prokaryotes) in oxygen-deficient water columns. As climate warming expands coastal oxygen minimum zones, ongoing and near-future changes may ultimately lead to increased methylmercury formation. However, little is known about the presence of aquatic mercury methylators before the Industrial Revolution, marked by increased mercury emissions and deposition in the environment. Here we have detected hgcA genes in Black Sea sedimentary archives, with the highest abundance 9,000–5,500 years ago when anoxic conditions were documented in the water column. Historical sedimentary and modern water column data on mercury methylators provide valuable insights for projecting future methylmercury production in aquatic ecosystems impacted by ongoing deoxygenation. It also underscores the potential impacts of climate change on human exposure to methylmercury from mercury-contaminated seafood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

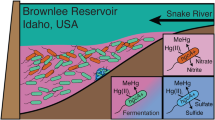

Methylmercury is a potent neurotoxic compound that poses an important risk to human health through the consumption of mercury-contaminated seafood1. This compound is formed via microbially mediated mercury (Hg) methylation, a process reported to occur in the absence of oxygen such as in oxygen-deprived aquatic ecosystems2,3. Consequently, elevated concentrations of methylmercury have recently been reported in oxygen-minimum zones4 and in deoxygenated coastal areas such as the Baltic Sea5, the Black Sea6 and fjords such as the euxinic Saanich Inlet7. In the context of ongoing climate warming, it is predicted that the expansion of coastal oxygen-minimum zones will become widespread, possibly leading to increased methylmercury formation. Climate-driven changes in marine ecosystems, particularly increased water temperatures leading to seasonal stratification, and climate-induced changes in rainfall patterns exacerbating nutrient loading are intensifying surface primary production in many regions, resulting in more frequent and intense algal blooms. Enhanced primary productivity leads to greater export of organic matter to subsurface waters, where its decomposition consumes oxygen and contributes to the expansion of oxygen-minimum zones and anoxia8. These low-oxygen conditions are known to favour the activity of anaerobic microorganisms capable of mercury methylation, thereby promoting the formation of methylmercury2. Apparent oxygen utilization, which reflects the difference between saturated and measured oxygen concentrations, serves as a useful proxy for oxygen consumption related to organic matter remineralization and can thus indicate regions with elevated potential for methylmercury production. As such, the interplay between climate-induced increases in primary productivity, resulting oxygen depletion and microbial activity is emerging as a key driver of methylmercury dynamics not only in the Black Sea but also across various stratified and hypoxic marine systems worldwide. Additionally, seasonal mixing returns nutrients and methylmercury to the upper part of the photic zone, simultaneously promoting primary productivity and the accumulation of methylmercury into higher trophic levels (for example, fish)9,10. Although microorganisms involved in Hg methylation, known as Hg methylators, have been found in the water column and surface sediments of deoxygenated ecosystems7,11,12,13, geobiological records need to be studied to elucidate whether low levels of naturally emitted Hg may have contributed to microbial Hg methylation soon after the development of permanent stratified, euxinic conditions, although probably to a much lesser extent than following the rise in anthropogenic Hg emissions. Furthermore, advancing our understanding of the extent to which anthropogenic inputs have influenced the abundance and diversity of Hg methylators remains a critical research question.

Particles from water columns carry favourable microenvironments for anaerobic and microaerophilic microorganisms as they provide them with carbon sources and nutrients14. As such, Hg methylators have been found to be prevalent in particulate organic matter in the Baltic Sea11 and Lake Geneva15. Those particles, originating mainly from terrestrial runoff and dead cells (for example, decaying plankton blooms), sink through the water column, eventually reaching the bottom and forming sediment. Thus, each sediment layer can reveal the geochemical and biological information of the palaeo-depositional environment16,17. Analysing DNA preserved in such sedimentary archives along with geochemical palaeoclimate proxies can be used for reconstructing the history of changes in aquatic biota concurrent with long-term environmental perturbations18,19. For instance, using the sedimentary DNA approach, More et al.20 reconstructed a 43-thousand-year record of long-term Protistan community responses to monsoon-triggered oxygen-minimum-zone expansion in the Northeastern Arabian Sea. Additionally, sedaDNA analysis of several lake sediments revealed an increase in the estimated abundance of merA genes that encode for an enzyme involved in Hg detoxification with the start of the Industrial Revolution21. Such detailed insights would be unattainable using traditional morphological identification of macro- and microfossils. Furthermore, it is now possible to go beyond mere taxonomic information (for example, metabarcoding) as information on key protein-coding genes can now be obtained from shotgun sequencing applied to sedimentary DNA22,23. Therefore, this analytical approach can inform about long-term changes in specific metabolic functions and the organisms mediating the process but has only been scarcely used for sedaDNA analyses

The Black Sea is an ideal study site to investigate the presence of Hg methylators using its sedimentary archive. It is the world’s largest and deepest permanently stratified basin, with a long history of anoxia in subsurface waters24 and is nowadays enriched in methylmercury6 and Hg methylators13. Moreover, it underwent a drastic change in salinity from freshwater to saline water after its reconnection with the Mediterranean Sea as a consequence of climate warming about 9.5 thousand calendar years before present (ka cal BP) (ref. 24), affecting the fauna as evident from a dramatic shift from freshwater to marine plankton16. Considering the long-term anoxia of the Black Sea, this study aimed to address the three main research questions: (1) what was the diversity and composition of Hg methylators in the Black Sea over the past 13,500 years? (2) Were the Hg methylators that prevailed in the permanently stratified anoxic Black Sea predating the Industrial Revolution genetically similar to lineages previously described13 from the oxygen-depleted extant water column? (3) Were their abundance and diversity shaped by well-known long-term palaeoenvironmental changes that occurred before and after the transition from a low productivity oxygenated glacial freshwater lake to a permanently stratified and anoxic, more productive brackish basin following the post-glacial reconnection with the Mediterranean Sea? We used a metagenomic approach combined with the marky-coco bioinformatic pipeline25 to unveil the historical record of potential Hg methylators, hereafter referred to as hgcA+ taxa, from Late Glacial and Holocene sediments of the Black Sea. The diversity and composition of hgcA inventories that prevailed during key Late Glacial and Holocene climate stages were compared with available data from those residing in the extant Black Sea13, exposed to anthropogenic Hg deposition. Our findings emphasize the importance of deoxygenation in shaping ecological niches for methylmercury production in aquatic ecosystems.

Hg methylators in the Black Sea sedimentary archives and the water column

The number of DNA sequences obtained from Black Sea sediment and water column metagenomes ranged between 4.21–5.89 and 2.47–4.49 million reads, respectively. From the sediment record and the water column, 10 and 91 distinct hgcA genes were respectively detected (Supplementary Table 1a,b). They were identified within 46 microbial taxa (National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) taxonomic identifiers, txid), with three exclusive to the sedimentary archives, 37 to the water column and six shared between both sample types (Fig. 1). In the sedimentary record, the hgcA+ taxa belong to Desulfobacterota, Chloroflexota, Actinobacteriota, Bacteroidota, Planctomycetota, Lentisphaerota, Spirochaetota and the FCB group (Fibrobacterota, Chlorobiota and Bacteroidota). The hgcA+ taxa from the water column belong to Desulfobacterota, Chloroflexota, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Planctomycetes, Lentisphaerae and Spirochaetes. A total of 15 hgcA genes were identified in metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) belonging to Desulfobacterota (Desulfobacterales, Desulfobulbales and unclassified Desulfobacterota), Chloroflexota (Anaerolineales), Bacteroidota (Bacteroidales), Planctomycetota (Phycisphaerales), Verrucomicrobiota (Kiritimatiellales) and the KSB1 candidate division. Within Desulfobacterota, hgcA+ MAGs were assigned to uncultured species such as Desulfacyla euxinica (MAGs id: NIOZ-UU19, NIOZ-UU27), Desulfobacula maris (NIOZ-UU16), Desulfatibia profunda (NIOZ-UU30) and Desulfobia pelagia (NIOZ-UU47).

The taxonomy of each txid is presented in Supplementary Table 1c.

Long-term changes in Hg methylation concurrent with environmental changes

Changes in temperature and humidity in the Black Sea region over the past 13.5 ka cal BP have been used to define chronozones. At 9.3 ka cal BP, the sea surface water temperature increased abruptly, reaching a maximum at 7.5 ka cal BP, as deduced from the temperature-dependent ratios Mg/Ca, Sr/Ca and δ18O trend (ratio of the stable oxygen isotopes oxygen-18 and oxygen-16) (Fig. S1 in ref. 26). Similar trends in the Late Glacial and Holocene sea surface temperatures and rainfall amounts can be observed in the Eastern Mediterranean records (Fig. S2 in ref. 27). In summary, the Younger Dryas, recognized as the coldest and driest period, was followed by the cool–dry Preboreal–Boreal, the warm–wet Atlantic, the warm–dry Sub-boreal and the cool–wet Sub-Atlantic chronozones (Fig. 2). The prokaryotic community and hgcA inventories from the Black Sea sediments exhibit significant structural differences (ANOSIM, p < 0.001; Fig. 2) when comparing layers deposited during the different chronozones, from the oldest (Younger Dryas) to the most recent (sub-Atlantic). In the water column, the hgcA inventories and the prokaryotic community also showed significant structural differences among the three defined oxygen zones (oxic, suboxic and euxinic, p < 0.005). Overall, Procrustes analysis showed a significant concordance between the structure of hgcA inventories and the prokaryotic community (r = 0.86, p = 0.017).

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plots showing the structure of hgcA inventories (left panel) and the prokaryotic community (right panel) from the sedimentary archives and the water column of the Black Sea. Oxygen concentrations are grouped based on three categories: oxic, ≥2 mgO2 l−1; suboxic water, >0–2 mgO2 l−1; euxinic water, 0 mgO2 l−1.

In terms of the composition of the prokaryotic community (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1d), large variations were observed across sediment chronozones, including major shifts for Alphaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria and Bacillota. Notably, higher proportions of Actinobacteriota were identified in the intervals spanning the Atlantic chronozone. The temporal changes in the abundance (normalized coverage values) of hgcA genes in Black Sea sedimentary archives (Fig. 3) revealed substantial oscillations in both the abundance and the composition of their hgcA inventories. In sediment layers corresponding to the Atlantic chronozone, the hgcA gene abundance consistently exceeded 0.15 while never reaching more than 0.12 in the older chronozones. The most abundant hgcA+ taxa belong to Desulfobacterota, Bacteroidota, Actinobacteriota and Spirochaetota. Both hgcA+ Desulfobacterota txid231684 and Actinobacteriota txid1883427 were barely detected before and after the Atlantic chronozone. The hgcA+ Lentisphaerae txid641407 was detected before the Atlantic chronozone but not after, except for the sediment layer dated to 6.0 ka cal BP. In the Atlantic chronozone, a hgcA+ Myxococcota (txid213495) was dominant, especially at 1.3 ka cal BP.

Oxygen zones (oxic, suboxic and anoxic) and chronozones (Sub-Atlantic, Sub-boreal, Atlantic, Preboreal–Boreal and Younger Dryas), according to Huang et al.24 and associated environmental conditions16, are displayed for metagenomes corresponding to the water column and sedimentary archives, respectively. Oxygen concentrations are grouped based on three categories: oxic, ≥2 mgO2 l−1; suboxic water, >0–2 mgO2 l−1; euxinic water, 0 mgO2 l−1.

From the top of the oxic zone to the bottom of the suboxic zone of the water column, the prokaryotic community showed a gradual increase in the proportion of Thaumarchaeota and a decrease in the proportions of Actinobacteriota and Bacillota. In contrast, the proportions of these groups displayed an opposite trend in the euxinic zone. A gradual increase in the abundance of hgcA genes was observed in the upper 130 m of the water column, followed by a decline with the lowest values found at 1,000 and 2,000 m depth (Fig. 3). The composition of hgcA inventories appeared to be similar in oxygen-depleted (~0.3 µmol kg−1) waters between 100 and 500 m water depths with abundant hgcA genes from Desulfobacterota (Desulfobacterales Desulfacyla sp.), Planctomycetota, Kiritimatiellaeota, Bacteroidetes (Bacteroidales) and Chloroflexota (Anaerolineales) (Fig. 3). At 1,000 and 2,000 m water depths, the abundance of hgcA genes from Kiritimatiellaeota and Desulfacyla sp. was found to be lower, resulting in a lower total abundance of hgcA genes.

Discussion

In this study, we report the first detection of hgcA genes, indicators of the presence of Hg methylators in Black Sea sediments deposited before the Industrial Revolution (that is, between 13.5 and 0.3 ka cal BP). We further observed an increased abundance of Hg methylators in the Black Sea with the establishment of permanent anoxic conditions.

We observed a lower diversity of Hg methylators in the sedimentary record compared to the water column, with only a few taxa shared between these sample types. This difference in diversity could be attributed to downcore variability in the level of DNA degradation and temporal changes in the flux and composition of particle-attached Hg methylators. During sediment burial, biological (for example, enzymatic degradation), chemical (for example, oxidation) and physical (for example, sediment compaction) processes contribute to the breakdown of DNA28. Over time, DNA and other molecules undergo fragmentation and chemical modification, leading to reduced detectability. However, in our study, higher proportions of hgcA genes were found in sediments deposited during the wet and warm (Atlantic chronozone; ~9.0–5.5 ka cal BP), also known as the mid-Holocene Climate Optimum29, compared to more recent layers, indicating a minimal, if any, gradual degradation of the hgcA gene’s molecular signal. Well-preserved ancient DNA in the sediment record of the present study was previously demonstrated based on significant correlations between copy numbers of ~500-bp-long 18S rRNA gene fragments from calcified and non-calcified haptophyte algae, which started to prevail in the Black Sea soon after the marine reconnection (~9 ka cal BP) and the concentrations of highly diagnostic and recalcitrant haptophyte lipid biomarkers (that is, long-chain alkenones)30. Moreover, up to 25% of the haptophyte 18S rRNA gene amplicons could be recovered from the high molecular weight fraction of the extracted DNA samples30. This suggests that our findings provide insights into past environmental conditions that led to changes in the Black Sea microbiota. As an alternative to DNA degradation issues, the differences in the diversity of potential Hg methylators within the water column and sediments could be attributed to the reduced survival rate of microorganisms from the water column post-burial31. Thus, because environmental factors shape microbial communities32, the difference in taxonomy between water and sediment samples may be the result of which aquatic microorganisms were selected by past environmental conditions22,33. The modern Black Sea is impacted by anthropogenic activities, such as excessive nutrient inflow, which has led to eutrophication34. Consequently, Hg methylators in the present-day Black Sea probably differ from those that existed thousands of years before the onset of anthropogenic activities related to the Industrial Revolution.

The higher abundance of Hg methylators detected during the Atlantic chronozone aligns with evidence of the transport of warm and humid air masses from the Atlantic to the Balkan Peninsula, resulting in this climate stage being the wettest and warmest since the start of the Holocene29. As a result of climate warming, saline seawater from the Mediterranean Sea initially flowed into the Black Sea at 9.4 ka due to post-glacial sea level rise, transforming it from a near-fresh (∼1–2 practical salinity unit (psu)) inland lake to an oligohaline (∼5–6 psu) basin connected to the global ocean24. By ∼6.9 ka, the Black Sea surface salinity had reached near-modern levels24. Due to the density difference, the heavier saline water settled at the bottom beneath the relatively fresher water, causing stratification. This stratification prevented the mixing of oxygenated surface waters with deeper layers. Subsequent consumption of dissolved organic matter by aerobic organo-heterotrophs resulted in the formation of anoxic bottom waters that became highly sulfidic through the activity of sulfate-reducing bacteria—key candidates for Hg methylation35. The ~100-m-thick oxygenated mixed surface waters are separated from the up to 2-km-deep euxinic bottom waters by a 30-m-thick oxygen-minimum zone devoid of sulfide. Consequently, the expansion of microaerophilic and anoxic conditions provided favourable conditions for Hg methylators to thrive. Organic-rich particles reaching deoxygenated water layers make optimal micro-anoxic niches14 in the Black Sea for Hg methylators, as previously reported in the Baltic Sea11. A notable example is the putative Hg methylator Desulfobacteriaceae (txid231684), currently the most abundant at depths between 170 and 500 m, covering the upper part of the euxinic water column. This group was also relatively prevalent in the sediments deposited during the Atlantic chronozone (~8–5 ka cal BP). The onset of the warm and humid Atlantic, which peaked at 8 ka cal BP (ref. 36), roughly coincides with the beginning of the deposition of the well-known organic carbon-rich sapropel in our core16. Sapropel deposition is ongoing; however, the organic carbon content in the sapropel from this chronozone (~ 15 wt%) was, on average, two to three times higher than that in the sapropel deposited during the warm but relatively dry Sub-boreal (~5.0–2.5 ka cal BP) and the Sub-Atlantic (2.5 ka BP to the present) chronozones in our core16. These results indicate that stratification and bottom water euxinia were particularly pronounced during the wettest and warmest climate stage of the Holocene, providing an extensive vertical gradient for this potential sulfate-reducing Hg methylator to thrive. Reported high total organic content (TOC) content during the Holocene Climate Maximum in the Atlantic chronozone37 could explain as well the relatively higher abundance of Hg methylators during this chronozone as organic-rich conditions may have contributed to the shifts of sulfate reducers to fermentative lifestyles, resulting in the undegraded DNA signal in this record. This hypothesis is in line with findings in the Arabian Sea sediment records showing higher proportions of putative denitrifiers during extended periods of oxygen-minimum zone expansions that resulted in the deposition of sediments with high TOC22.

In contrast, metagenomic reads of putative nitrifying Thaumarchaeota, which were not a source of the hgcA gene but were relatively most abundant in the oxygen-minimum zone between 100 and 170 m, comprised only a very small proportion of the total reads in the underlying sediments, including the Atlantic chronozone core section. This was initially unexpected, as their diagnostic lipid biomarker, crenarchaeol, had previously been reported from Black Sea sediment traps and surface sediments at a different coring location, suggesting an effective vertical flux of their biomass to the sediment floor38. The difference in Hg methylators’ diversity noticed between the modern-day water column and, most notably, those identified from the wet and warm Atlantic chronozone may also be attributed to increased drainage of stagnant anaerobic soils of flooded riparian forests aligning the Danube River39 and subsequent deposition and burial of soil particulate organic matter and associated microorganisms to the coring location with Hg methylators from anaerobic soil niches as potential microbial hitchhikers. The prevalence of Actinobacteriota, well-recognized soil microorganisms, in the sediment layers of the Atlantic chronozone supports the evidence of soil organic matter contribution to the sedimentary DNA pool recovered in our study. A higher proportion of sedimentary metagenomic reads of Actinobacteriota over Thaumarchaeota suggests that terrestrial runoff contributed more to the flux of microbial biomass, including Hg methylators and their subsequent burial in the sedimentary record, than the vertical flux of pelagic taxa, including Hg methylators that were seeded from the past suboxic and anoxic zonations in the water column.

Over recent decades, particularly following the Industrial Revolution, two major environmental impacts have become increasingly evident: the accelerated pace of global warming40 and the eutrophication of aquatic ecosystems driven by excessive nutrient input from anthropogenic activities41 and increased Hg deposition42,43. Marsicek et al.44 showed that recent temperatures have exceeded the range of centennial mean temperatures during the Holocene in North America, Europe and the northern marine margins. The Black Sea has experienced noticeable changes in recent decades. These include the intensification of algal blooms, particularly in the northwestern region34,45, and an expansion of the anoxic zone, with a marked shallowing of the overlying oxic photic zone46,47. According to a numerical 1-D model simulating the time evolution (1850–2050) of Hg species, anthropogenic Hg in the Black Sea water column is estimated to comprise approximately 85–93% of the total Hg input, with net Hg methylation in the anoxic waters of the Black Sea reaching ~11 kmol yr−1 (ref. 6). Notably, data from the 2013 GEOTRACES MEDBlack cruise reveal the highest methylmercury/mercury percentage (up to 57%) in permanently anoxic waters, comparable to subsurface maxima in the oxygenated open ocean6. This knowledge about Hg methylators in the past anoxic Black Sea (present study) and the water column13 raised a growing concern about the future of the Black Sea as a hotspot for methylmercury production due to shallowing of the oxic photic zone replaced by deoxygenated waters.

The successful recovery of the sedimentary DNA from microorganisms capable of producing methylmercury in the past anoxic Black Sea underscores the potential of metagenomics, not only to reconstruct the past distribution of microbial communities but also to reveal functional traits preserved in potentially degraded DNA, offering novel insights into historical biogeochemical processes. It also provides valuable insights into the potential response of microbial communities involved in methylmercury formation to future environmental changes, especially in the context of climate-driven deoxygenation of coastal waters, which would result in elevated concentrations of neurotoxic methylmercury, posing risks to human exposure through seafood consumption.

Methods

Obtention of sediment metagenomes

A detailed description of the approaches used to recover and subsample a giant gravity core (GGC18), organic- and geochemical analysis and infer changes in the palaeo-depositional environment and the age model of GGC18 have been published elsewhere37,39,48. Briefly, GGC18 was recovered from a water depth of 971 m in 2006 from the western part of the Black Sea (42° 46.569′ N, 28° 40.647′ E) on board the R/V Akademic (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences) in 2006. After splitting the core in half on board, the R/V Akademik subsamples were collected at 1-cm resolution using sterile headless syringes, avoiding cross contamination. They were stored in liquid nitrogen and kept frozen until further processing. Total DNA was extracted from 8 to 10 g of wet-weight sediment sampled at a 1-cm resolution using the PowerMax Soil DNA Isolation Kit (Mo Bio) in the clean lab dedicated to ancient DNA analysis at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution48. Co-extracted PCR-inhibiting substances such as humic acids were efficiently removed using the OneStep PCR Inhibitor Removal Kit (Zymo Research). Nineteen intervals spanning 13.5 ka of deposition were available for metagenomic library preparations. Metagenomic libraries were prepared with a 50-ng template DNA using the NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England BioLabs Inc.) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The amplification involved 13–15 cycles. The resulting barcoded libraries (200–500 base pairs) were gel purified with the Monarch DNA Gel Extraction Kit (New England BioLabs Inc.) and sent to the Australian Genomic Research Facility in Perth for final quality control and sequencing using the Illumina HiSeq2500 sequencing (2 × 100-bp paired-end chemistry).

Generation of water metagenomes

The Phoxy cruise 64PE371 was conducted on 9 and 10 June 2013 in the western gyre of the Black Sea. Suspended particulate matter was collected from 15 depths across the oxygen gradient in the water column (from 50 to 2,000 m depth) at sampling station 2 (42° 53.4′ N, 30° 40.2′ E, 2,107 m depth, at 72 km from the MedBlack station 2 and visited 35 days earlier) with McLane WTS-LV in situ pumps (McLane Laboratories Inc.) on pre-combusted glass fibre filters with 142-mm diameter and 0.7-μm nominal pore size, further stored at −80 °C. DNA was extracted from sections of 15 glass fibre filters (1/8th of each filter from 50 to 130 m depth and 1/4th of each filter from 170 to 2,000 m depth) with the RNA PowerSoil Total Isolation Kit plus the DNA elution accessory (Mo Bio Laboratories) as previously described49. The 15 DNA extracts were used to prepare TruSeq nano libraries, sequenced with Illumina MiSeq (five samples multiplexed per lane) at Utrecht Sequencing Facility, generating 4.5 × 107 paired-end reads (2 × 250 base pairs).

Bioinformatics

Metagenomes from the water column and the sediments were analysed using the same software. First, fastp (v0.23.2)50 was used to quality trim the data with the following parameters: -q 30 -l 25 --detect_adapter_for_pe --trim_poly_g --trim_poly_x. The two co-assemblies generated using the assembler MEGAHIT (v 1.1.2)51 with default settings yielded 6,764,645 and 971,921 contigs for water and sediment metagenomes, respectively. Prodigal (v2.6.2)52 was used for prokaryotic gene prediction and detected 9,124,496 and 1,435,036 protein-coding genes from water and sediment metagenomes, respectively. The DNA reads from the metagenomes were mapped against the contigs from their respective co-assemblies with bowtie2, and the resulting.sam files were converted to.bam files using samtools (v1.9)53. The.bam files and the prodigal output.gff file were used to estimate read counts using the featureCounts function from subread (1.5.2)54. The overall community composition from both water and sediment metagenomes was evaluated using the kraken2 and bracken functions from kraken2 (v2.0.8)55 and bracken (v2.5)56,57,58,59, respectively, with default settings for the taxonomic classification of the sequences obtained in the metagenomes. To detect hgcA and hgcB homologues, we used the procedure described in Capo et al.25. Coverage values of hgcA genes were calculated as the number of reads mapped to the gene divided by its length in base pairs and were further normalized by dividing them by the coverage values of the marker gene rpoB. Some hgcA genes were found in previously reconstructed metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs)60.

Statistical analysis

A principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was performed using the R package vegan61. Specifically, the function wcmdscale was applied to a Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrix built with the function vegdist from (hgcA+ taxa abundance table (hgcA inventories, marky-coco analysis) and the taxa abundance table (overall prokaryotic community, kraken2-bracken analysis). An ANOSIM analysis was performed using PAST62 to study the differences in the distribution of hgcA+ microbial groups and the whole prokaryotic community along the sediment records comparing six selected climate periods. A PROTEST permutation procedure analysis (1,000 permutations) was performed using the function Procrustes from the vegan package to evaluate the level of concordance between the structure differences in hgcA inventories and the whole prokaryotic community.

Data availability

The sediment metagenomes have been submitted to MG-RAST, and accession numbers are available in More et al.37. The 15 water metagenomes (raw data) have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject ID PRJNA649215.

References

Selin, N. E. Global biogeochemical cycling of mercury: a review. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 34, 43–63 (2009).

Bravo, A. G. & Cosio, C. Biotic formation of methylmercury: a bio–physico–chemical conundrum. Limnol. Oceanogr. 65, 1010–1027 (2020).

Wang, Y., Wu, P. & Zhang, Y. Climate-driven changes of global marine mercury cycles in 2100. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2202488120 (2023).

Adams, H. M., Cui, X., Lamborg, C. H. & Schartup, A. T. Dimethylmercury as a source of monomethylmercury in a highly productive upwelling system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 10591–10600 (2024).

Soerensen, A. L. et al. Deciphering the role of water column redoxclines on methylmercury cycling using speciation modeling and observations from the Baltic Sea. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 32, 1498–1513 (2018).

Rosati, G. et al. Mercury in the Black Sea: new insights from measurements and numerical modeling. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 32, 529–550 (2018).

Lin, H. et al. Mercury methylation by metabolically versatile and cosmopolitan marine bacteria. ISME J. 15, 1810–1825 (2021).

Friedrich, J. et al. Investigating hypoxia in aquatic environments: diverse approaches to addressing a complex phenomenon. Biogeosciences 11, 1215–1259 (2014).

Schartup, A. T. et al. Climate change and overfishing increase neurotoxicant in marine predators. Nature 572, 648–650 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Dutkiewicz, S. & Sunderland, E. M. Impacts of climate change on methylmercury formation and bioaccumulation in the 21st century ocean. One Earth 4, 279–288 (2021).

Capo, E. et al. Deltaproteobacteria and Spirochaetes-like bacteria are abundant putative mercury methylators in oxygen-deficient water and marine particles in the Baltic Sea. Front. Microbiol. 11, 574080 (2020).

Capo, E. et al. Oxygen-deficient water zones in the Baltic Sea promote uncharacterized Hg methylating microorganisms in underlying sediments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 67, 135–146 (2022).

Cabrol, L. et al. Redox gradient shapes the abundance and diversity of mercury-methylating microorganisms along the water column of the Black Sea. mSystems 8, e00537-23 (2023).

Bianchi, D., Weber, T. S., Kiko, R. & Deutsch, C. Global niche of marine anaerobic metabolisms expanded by particle microenvironments. Nat. Geosci. 11, 263–268 (2018).

Capo, E. et al. Anaerobic mercury methylators inhabit sinking particles of oxic water columns. Water Res. 229, 119368 (2023).

Coolen, M. J. L. et al. Evolution of the plankton paleome in the Black Sea from the deglacial to Anthropocene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 8609–8614 (2013).

Gregory-Eaves, I. & Smol, J. P. in Wetzel’s Limnology 4th edn (eds Jones, I. D. & Smol, J. P.) 1015–1043 (Academic Press, 2024); https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-822701-5.00030-6

Armbrecht, L. H. The potential of sedimentary ancient DNA to reconstruct past ocean ecosystems. Oceanography 33, 116–123 (2020).

Capo, E. et al. Environmental paleomicrobiology: using DNA preserved in aquatic sediments to its full potential. Environ. Microbiol. 24, 2201–2209 (2022).

More, K. D. et al. A 43 kyr record of protist communities and their response to oxygen minimum zone variability in the northeastern Arabian Sea. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 496, 248–256 (2018).

Ruuskanen, M. O., Aris-Brosou, S. & Poulain, A. J. Swift evolutionary response of microbes to a rise in anthropogenic mercury in the Northern Hemisphere. ISME J. 14, 788–800 (2020).

Orsi, W. D. et al. Climate oscillations reflected within the microbiome of Arabian Sea sediments. Sci. Rep. 7, 6040 (2017).

Armbrecht, L. et al. Ancient marine sediment DNA reveals diatom transition in Antarctica. Nat. Commun. 13, 5787 (2022).

Huang, Y., Zheng, Y., Heng, P., Giosan, L. & Coolen, M. J. L. Black Sea paleosalinity evolution since the last deglaciation reconstructed from alkenone-inferred Isochrysidales diversity. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 564, 116881 (2021).

Capo, E. et al. A consensus protocol for the recovery of mercury methylation genes from metagenomes. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 23, 190–204 (2023).

Bahr, A. et al. Abrupt changes of temperature and water chemistry in the late Pleistocene and early Holocene Black Sea. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 9, Q01004 (2008).

Göktürk, O. M. et al. Climate on the southern Black Sea coast during the Holocene: implications from the Sofular Cave record. Quat. Sci. Rev. 30, 2433–2445 (2011).

Corinaldesi, C., Beolchini, F. & Dell’anno, A. Damage and degradation rates of extracellular DNA in marine sediments: implications for the preservation of gene sequences. Mol. Ecol. 17, 3939–3951 (2008).

Birks, H. J. B. in Natural Climate Variability and Global Warming (eds Battarbee, R. W. & Binney, H. A.) 7–57 (John Wiley & Sons, 2008); https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444300932.ch2

Coolen, M. J. L. et al. Ancient DNA derived from alkenone-biosynthesizing haptophytes and other algae in Holocene sediments from the Black Sea. Paleoceanography https://doi.org/10.1029/2005PA001188 (2006).

Vuillemin, A., Coolen, M. J. L., Kallmeyer, J., Liebner, S. & Bertilsson, S. in Tracking Environmental Change Using Lake Sediments: Volume 6: Sedimentary DNA (eds Capo, E. et al.) 85–151 (Springer International Publishing Cham, 2023); https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-43799-1_4

Li, S.-J. et al. Microbial communities evolve faster in extreme environments. Sci. Rep. 4, 6205 (2014).

Møller, T. E., van der Bilt, W. G. M., Roerdink, D. L. & Jørgensen, S. L. Microbial community structure in Arctic lake sediments reflect variations in Holocene climate conditions. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1520 (2020).

Silkin, V. A. et al. Drivers of phytoplankton blooms in the northeastern Black Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 138, 274–284 (2019).

King, J. K., Kostka, J. E., Frischer, M. E. & Saunders, F. M. Sulfate-reducing bacteria methylate mercury at variable rates in pure culture and in marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 2430–2437 (2000).

Filipova-Marinova, M., Pavlov, D., Coolen, M. & Giosan, L. First high-resolution marinopalynological stratigraphy of Late Quaternary sediments from the central part of the Bulgarian Black Sea area. Quat. Int. 293, 170–183 (2013).

More, K. D., Giosan, L., Grice, K. & Coolen, M. J. L. Holocene paleodepositional changes reflected in the sedimentary microbiome of the Black Sea. Geobiology 17, 436–448 (2019).

Wakeham, S. G., Lewis, C. M., Hopmans, E. C., Schouten, S. & Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. Archaea mediate anaerobic oxidation of methane in deep euxinic waters of the Black Sea. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 1359–1374 (2003).

Giosan, L. et al. Early Anthropogenic transformation of the Danube-Black Sea system. Sci. Rep. 2, 582 (2012).

Abram, N. J. et al. Early onset of industrial-era warming across the oceans and continents. Nature 536, 411–418 (2016).

de Jonge, V. N., Elliott, M. & Orive, E. Causes, historical development, effects and future challenges of a common environmental problem: eutrophication. In Nutrients and Eutrophication in Estuaries and Coastal Waters: Proc. 31st Symposium of the Estuarine and Coastal Sciences Association (ECSA) (eds Orive, E. et al.) 1–19 (Springer, 2002); https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-2464-7_1

Mason, R. P. et al. Mercury biogeochemical cycling in the ocean and policy implications. Environ. Res. 119, 101–117 (2012).

Cooke, C. A., Martínez-Cortizas, A., Bindler, R. & Sexauer Gustin, M. Environmental archives of atmospheric Hg deposition – a review. Sci. Total Environ. 709, 134800 (2020).

Marsicek, J., Shuman, B. N., Bartlein, P. J., Shafer, S. L. & Brewer, S. Reconciling divergent trends and millennial variations in Holocene temperatures. Nature 554, 92–96 (2018).

Bakan, G. & Büyükgüngör, H. The Black Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 41, 24–43 (2000).

Pakhomova, S. et al. Interannual variability of the Black Sea proper oxygen and nutrients regime: the role of climatic and anthropogenic forcing. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 140, 134–145 (2014).

Vidnichuk, A. V. & Konovalov, S. K. Changes in the oxygen regime in the deep part of the Black Sea in 1980–2019. Phys. Oceanogr. 28, 180–190 (2021).

Coolen, M. J. L. et al. DNA and lipid molecular stratigraphic records of haptophyte succession in the Black Sea during the Holocene. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 284, 610–621 (2009).

Villanueva, L. et al. Bridging the membrane lipid divide: bacteria of the FCB group superphylum have the potential to synthesize archaeal ether lipids. ISME J. 15, 168–182 (2021).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Li, D. et al. MEGAHIT v1.0: a fast and scalable metagenome assembler driven by advanced methodologies and community practices. Methods 102, 3–11 (2016).

Hyatt, D. et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinform. 11, 119 (2010).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. The subread aligner: fast, accurate and scalable read mapping by seed-and-vote. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e108 (2013).

Wood, D. E., Lu, J. & Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 20, 257 (2019).

Lu, J., Breitwieser, F. P., Thielen, P. & Salzberg, S. L. Bracken: estimating species abundance in metagenomics data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 3, e104 (2017).

Gionfriddo, C. M. et al. An improved hgcAB primer set and direct high-throughput sequencing expand Hg-methylator diversity in nature. Front. Microbiol. 11, 541554 (2020).

Finn, R. D., Clements, J. & Eddy, S. R. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W29–W37 (2011).

Matsen, F. A., Kodner, R. B. & Armbrust, E. V. pplacer: linear time maximum-likelihood and Bayesian phylogenetic placement of sequences onto a fixed reference tree. BMC Bioinform. 11, 538 (2010).

van Vliet, D. M. et al. The bacterial sulfur cycle in expanding dysoxic and euxinic marine waters. Environ. Microbiol. 23, 2834–2857 (2021).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. Version 2.6–10 https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.vegan (2001).

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T. & Ryan, P. D. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 4, 4 (2001).

Acknowledgements

E.C. was funded by the Swedish Research Council VR (VR starting grant 2023-03504). I.B.A. was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (project number 221959) and the Agustin Lombard grant from the SPHN Society of Geneva. M.P. was funded by Kempestilferna. E.B. was funded by the Swedish Research Council Formas (grant 2018-01031). M.J.L.C. was funded through the US National Science Foundation (OCE grants 0602423 and 0825020). The computations were enabled by resources provided by the National Academic Infrastructure for Supercomputing in Sweden (NAISS), partially funded by the Swedish Research Council through grant agreement numbers 2023/5-183 and 2023/6-139. We thank the SNP&SEQ Technology Platform in Uppsala, which is a part of the National Genomics Infrastructure (NGI) Sweden, and the Science for Life Laboratory for the sequencing. The SNP&SEQ Platform is also supported by the Swedish Research Council and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Umea University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Z. performed bioinformatics analysis and data analysis and co-wrote the first draft of the manuscript. I.B.A., K.D.M. and M.P. performed bioinformatics analysis and data analysis and edited the manuscript draft. E.B., A.G.B. and S.B. contributed to method development for the bioinformatics and edited the manuscript draft. M.J.L.C. obtained the sediment samples and DNA dataset used in this study. E.C. designed this study, performed bioinformatic analysis and data analysis, and co-wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Water thanks Yanxu Zhang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 1

a, List of hgcA genes from water metagenomes. b, List of hgcA genes from sediment metagenomes. c, hgcA+ taxa abundance table. d, Prokaryotic community.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhong, M., Barrenechea Angeles, I., More, K.D. et al. Climate-driven deoxygenation promoted potential mercury methylators in the past Black Sea water column. Nat Water 3, 1389–1396 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-025-00526-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-025-00526-4