Abstract

The United States is experiencing significant social change, compelling white Americans to grapple more directly with their white identity. This paper examines how white Americans manage their identity amidst societal shifts using a recently developed measure of advantaged identity management, representative data (N = 2648), and latent profile analysis. The findings reveal five subgroups of white Americans, each managing their identity differently. Four profiles correspond to the main advantaged identity management strategies (defend (n = 251), deny (n = 528), distance (n = 694), dismantle (n = 612)), with a fifth using strategies flexibly (n = 563). We examined how valuing hierarchy, meritocracy, and egalitarianism predicted membership in these subgroups, and most of our predictions about how these values would predict membership were supported. These profiles show contrasting attitudes toward social change, with defender-deniers opposing, denier-distancers moderately opposing, distancers remaining neutral, and dismantlers supporting change. These findings provide empirical evidence for a recently theorized model of white identity management and suggest that how white Americans manage their identity has important implications for social change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The United States is experiencing profound social change. Amid demographic shifts that will soon render white Americans a minority1, Black Lives Matter has become the largest social movement in U.S. history2. The fight against structural racism has garnered unprecedented national attention3—while debates rage over how (and indeed whether) racial history in schools4. Such developments are transforming American race relations and political life in ways that are only beginning to come into focus. One likely outcome of this is that white Americans will be forced, more than ever before, to grapple with their identities as advantaged social actors. Yet psychologists know relatively little about how advantaged group members think about their privileged social identities5,6,7. We address this gap by examining how different groups of white Americans manage conflict between their values and racial privilege and testing the recently proposed 4-D model of advantaged identity management. To this end, the present work leverages a recently developed measure of advantaged identity management8, nationally representative data on white Americans’ attitudes, and a person-centered data-analytic approach.

Identity management and social change

Psychologists have long recognized that how disadvantaged groups manage their identities can shape social change. For example, social identity theory identifies three identity management strategies used by the disadvantaged: social competition, social creativity, and individual mobility—only one of which (social competition) is consistently linked to collective action and efforts for social change9,10. Recently, there has been growing recognition that members of advantaged groups also have identity-management needs that shape their attitudes and behaviors concerning social change, though these needs have received far less systematic research attention. For example, Phillips & Lowery (2018)11 argue that the existence of privilege associated with whiteness induces threat and necessitates identity management, and theorize about some of the individual and systemic ways white Americans are protected from this threat. Knowles et al.5 integrated the limited literature on white identity management with other research on white and advantaged identity, to propose the 3-D model of white identity management. More recently, Shuman et al.8 expanded this model framework into the 4-D model, adding another management strategy, broadening it to advantaged groups generally, and developing a measure to allow for the empirical testing of this model. However, until now this 4-D model and its underlying theory and assumptions have not been directly empirically tested, which we aim to do in this paper.

Testing a theory of advantaged identity management

The 4-D model5,8 argues that privilege and social change evoke different threats and defensive responses based on the values held by advantaged group members. Those who value dominance and hierarchy likely experience status threat, or the concern that they will lose their material advantages. Those who strongly value achievement and meritocracy may face meritocratic threat, or a fear that group privilege calls their accomplishments into question. Finally, those who endorse egalitarian values may feel moral-image threat, or concern that their membership in a group guilty of past or present wrongdoing reflects negatively on them.

Different threats evoke different identity-management strategies5,8. The defend strategy, in which one affirms the legitimacy and, ultimately, the stability of the intergroup hierarchy, is useful in coping with status threat. The deny strategy, in which one underplays the amount of inequality in society, is effective in dispelling both status and meritocratic threats. Obscuring the hierarchy both renders it safe from critique and also shields the self against the power of group advantage to discount personal accomplishments. The distancing from identity and distancing from inequality strategies, in which members of advantaged groups eschew thoughts of group identity or come to regard inequality as not personally relevant, combat meritocratic and moral-image threats by summarily shielding the self from the negative implications of advantaged-group membership. Finally, the dismantling strategy, in which the advantaged endorse actions and policies that reduce their privilege, dispels moral-image threats by recasting the group as committed to the values of fairness and equity.

The 4-D model of advantaged identity management posits that differences in people’s values lead to the emergence of distinct subgroups of white Americans that rely on different identity-management strategies. This research aims to identify subgroups within the advantaged group based on their endorsement of the various strategies and to relate these profiles to individual differences in underlying social values. This perspective is in line with a growing line of work in the study of white identity that argues that it is not just the level of identification but also the content of one’s white identity that determines one’s racial attitudes12,13, and helps to answer a recent call for research on white identity that allows for the measurement of different types of white identity14. Moreover, it grounds these different types in a theoretical framework that shows how they emerge from different values which lead to the experience of different threats. Drawing on recent work that, like ours, seeks to identify subgroups within a population of interest15, the present work leverages latent profile analysis (LPA), a person-centered (i.e., clustering) technique. Finally, we seek to document the downstream consequences of identity-management profiles for white Americans’ attitudes toward social change.

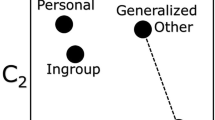

Predicted antecedents and outcomes of white identity-management strategies

We expect to find at least one latent group of white Americans characterized by high levels of each identity-management strategy (i.e., defend, deny, distance, and dismantle). We anticipate that participants’ values will predict their group membership— such that valuing hierarchy predicts membership in the defender and denier groups, valuing meritocracy predicts membership in the denier and distancer groups, and valuing egalitarianism predicts membership in the distancer and dismantler groups. Finally, these groups should react differently to social change: Defenders should strongly and actively oppose change, deniers should moderately resist change8,16, distancers should be more passive and neither actively oppose nor support change8,17, and dismantlers should actively support social change18. Figure 1 summarizes the expected subgroups, which values predict membership in each group, and the stance toward social change associated with each.

The structure of this figure was adapted from Lizzio-Wilson, et al.15

Finally, we also tested a potential intervention for increasing the support for social change among at least some classes. One method for attempting to increase support for policies that would advance equality has been to frame inequality in different ways—that is, either as advantages enjoyed by one group or disadvantages experienced by another. A recent study found this intervention was effective in increasing support to address income inequality19. Therefore, we aimed to test its effectiveness in the racial context, however, we did not expect it to be effective for all white Americans. Given that the strategies reflect the ways in which white Americans understand racial advantage, their choice of strategies should shape reactions to inequality frames that do (or do not) highlight that advantage. Namely, we expect that Dismantlers, who are highly aware of their privilege and motivated by the moral-image threat it poses5, will be more supportive of redistributive policies when inequality is framed as ingroup advantage18, because this framing triggers their main motivation. On the other hand, Distancers, who recognize the existence of inequality but attempt to distance themselves from privilege, should react more positively to framings of inequality as disadvantages faced by Black Americans—as this does not directly connect them to the problem. Further, we predict that Deniers, who do not believe inequality is a major problem, will be less supportive of policies regardless of framing. Defenders, who are committed to defending the racial hierarchy, will likely be strongly opposed to any policies advancing equality regardless of framing.

The current study

In sum, advantaged identity management has received relatively little research attention. Knowles et al.5 and Shuman et al.8 have integrated existing research into a theoretical model, the 4-D model, which has yet to be directly tested. We aim to provide an empirical test of this model in the context of U.S. race relations, and thus capture how white Americans currently understand their privileged position. Specifically, based on the 4-D model, we expect (a) subgroups of white Americans characterized by stable combinations of identity-management strategies, (b) specific values to predict subgroup membership, and (c) subgroups to differ meaningfully in their orientation toward social change and whether a framing intervention can shift support among some groups.

Method

To answer these questions, we conducted two studies: The first reanalyzed data collected during the validation of a measure of advantaged identity management which received ethics approval from Hebrew University (data and ethics approvals publicly available at https://zenodo.org/records/81907148,20) using person-centered analytic techniques. As the first study used a convenience sample and thus may not accurately represent white Americans, the second study replicates these findings in a high-quality nationally representative sample collected through NORC’s Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences (TESS) initiative. Study 2 was approved by the IRB at New York University. We present the two studies in parallel to facilitate direct comparisons between their results. Despite being similar, the studies differed in three respects. First, Study 1 included a measure of descriptive meritocracy (i.e., beliefs about whether the world is meritocratic), whereas Study 2 used a measure of prescriptive meritocracy (i.e., beliefs about whether the world should be meritocratic) that we felt better operationalized meritocratic values. Second, Study 1 included several measures gauging various attitudes relevant to social change, whereas Study 2 included a single, general measure, because of the length limitations for TESS studies. Third, Study 1 was entirely correlational, whereas Study 2 included an experiment examining whether the manner in which inequality is framed19 has different effects on the emergent subgroups’ social-change attitudes. This was included to test a potential intervention that might increase support for equality among some subgroups of white Americans. The materials, preregistrations, data, and code for all analyses are publicly accessible at https://osf.io/xgh9c/. Study 1 was preregistered after data collection (as it used existing data) but before running any analysis other than the LPA, as a result, the profile selection strategy for Study 1 was not pre-registered. Study 2 was preregistered before data collection, and any deviations from the pre-registrations are noted. In the Study 1 preregistration, we specify that the values of status, meritocracy, and egalitarianism would be measured using three values from the Schwartz value circumplex—namely, power, achievement, and universalism. However, after observing that these measures were low in internal reliability and produced generally weak results, we elected to test our hypotheses using measures that more directly tapped the values of hierarchy and meritocracy (i.e., SDO and the meritocracy scale). While this represents a deviation from the Study 1 preregistration, Study 2 is a preregistered replication of the reported analyses.

Participants

Study 1

1120 participants were recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, after pre-registered exclusions (for more detail see Study 1 Supplemental Methods) this left a final sample of 1028 non-Hispanic white Americans (Self-reported gender: 530 women, 494 men, 4 other; Mage = 40.8 years; 42% liberal, 15% moderate, 43% conservative) who participated between September 2020 and June 2021 in the course of developing the advantaged identity management scale (Shuman et al.8, Studies 2, 3, and 5). The data used in the present research were originally drawn from three separate samples, which we analyze integratively21 due to procedural similarities between the studies. Importantly, not all of the original studies contained the full set of measures relevant to our analyses: Only studies 3 and 5 contained measures useful in testing hypotheses related to values and only Study 5 contained outcome variables of interest. Consequently, we use the full sample of 1028 when conducting the LPA to identify subgroups in the population, but a sub-sample of 725 participants when testing hypotheses regarding values and a subsample of 520 when testing hypotheses concerning social-political outcomes (for more details regarding the integrative data analysis see study 1 supplemental methods).

Study 2

A nationally representative sample of 1631 non-Hispanic white Americans was recruited through NORC’s AmeriSpeak Panel as part of the NSF-funded Time-Sharing Experiments in the Social Sciences (TESS). This sample was nationally representative in terms of gender, age, education, and geography (census division; for more detail regarding NORC’s sampling procedures and methods, see the OSF page and https://amerispeak.norc.org/us/en/amerispeak/about-amerispeak/panel-design.html). Of these, 11 participants (0.7% of the sample) were excluded for entering the same answer consecutively to most survey questions (greater than 21 out of 33). The final sample consisted of 1620 participants (Self-reported gender: 782 women and 838 men; Mage = 51.6; 25% liberal, 45% moderate, 30% conservative). Dziak, et al.22 conducted simulations indicating that a sample of at least 1,620 is needed for 80% power in an LPA with five indicators and relatively similar profiles.

Procedure

Study 1

Participants completed the advantaged identity management scale, scales measuring values, and scales measuring social and political outcomes.

Study 2

Participants first completed the value measures, followed by the advantaged identity management scale. Then, participants were randomly assigned to read an infographic about racial inequality, adapted from Dietze & Craig (2020)19, that framed racial inequality either as advantages experienced by white Americans or disadvantages experienced by Black Americans. Specifically, the infographic highlights four statistics demonstrating racial inequality in four different domains education, employment, healthcare, and criminal justice. These statistics were either framed as an advantage for white Americans (e.g. “School districts serving predominately White communities receive $23 billion more in funding than their Black counterparts) or a disadvantage for Black Americans (e.g. “School districts serving predominately Black communities receive $23 billion less in funding than their White counterparts, see Study 2 supplemental methods for the full infographics). Participants then completed a scale measuring support for various policies to address inequality.

Measures

We report the measures for studies 1 and 2 together as they were very similar and simply note differences where relevant. All items were measured on a scale of “1 – Strongly Disagree” to “7 – Strongly Agree” unless otherwise stated.

Values. The following scales were used to measure the three values theorized to influence membership in different subgroups of white Americans:

Hierarchy was assessed using the Social Dominance Orientation scale23, as SDO captures a general preference for hierarchy in intergroup relations (e.g., “Superior groups should dominate inferior groups”; α = 0.84). In Study 2, we used three items (α = 0.66) due to space limitations in the TESS survey.

Meritocracy. In study 1, we used the Support for Meritocracy scale24. This scale captures people’s descriptive beliefs about whether the world functions meritocratically (e.g., “Anyone who is willing to work hard has a good chance of succeeding”; α = 0.93). In study 2, we shifted to a measure of prescriptive meritocracy beliefs, using three items from the Preference for the Merit Principle scale (Davey, et al.25, e.g., “In life, people ought to get what they deserve based on their hard work, even if this means some people are penniless”; α = 0.66).

Egalitarianism was assessed using26 three-item Universalism scale, as this instrument gauges the priority one places on creating a society that treats others equally. Respondents are asked to rate the importance they place on the values of “social justice,” “world at peace”, “and equality” as “life-guiding principles.” Participants made their responses on a −1 to 7 scale labeled as follows: “−1 (opposed to my principles),” “0 (not important),” “3 (important),” and “7 (of supreme importance)” (α = 0.81, 0.89).

White Identity Management Strategies. Identity management strategies were measured using the advantaged identity management scale developed by Shuman et al.8 in both studies, including the Defend subscale (e.g. “The inequalities that exist between Black and white Americans are a justified outcome of the real differences between the groups”; α = 0.91, 0.86), theDeny subscale (e.g., “The amount of inequality between Black and white Americans is actually quite small”; α = 0.95, 0.91), the Distance from Inequality subscale (e.g., “I have never personally benefited from the inequality that exists between Black and white Americans, though others might have”; α = 0.82, 0.72), the Distance from Identity subscale (e.g., “It bothers me when people focus on my racial identity rather than on the things that define me as an individual”; α = 0.82, 0.72), and the Dismantle subscale (e.g., “I think white Americans need to give up some of the privileges they have in order to create a more equal society”; α = 0.94, 0.92).

Social and Political Outcomes. Study 1 included measures of several social and political outcomes. We report effects involving all these variables in the supplementary materials (see Study 1 supplemental results), but in the main text focuses only on those most relevant for characterizing each subgroups’ attitudes concerning social change. Study 2 had one brief measure due to TESS length restrictions.

Study 1 Outcomes

Principle-Implementation Gap. We measured this gap in a manner similar to Tuch & Hughes (1996)27. Support for the principle of equality was assessed using four items (e.g., “Ideally, white and black Americans should be relatively equal in terms of wealth and economic status”; α = 0.88). Then, support for the implementation of equality was gauged by asking participants to rate their support for four policies (e.g., “spending more money on the schools in largely black neighborhoods, especially for preschool and early education programs”; α = 0.91).

Support for Voting Restrictions. One way in which white people can bolster their privileged position in the intergroup hierarchy is by restricting minority voting rights. In this measure, participants were prompted as follows: “Recently, a number of state legislatures have proposed changes to voting rules in their states, despite criticism that these changes will primarily make it more difficult for lower-income Americans, African Americans, and other minorities to vote.” Participants then rated their support for an array of restrictive measures (e.g., “Ending early voting”; α = 0.89).

Support for Affirmative Action. Participants’ support for affirmative action was measured using a scale developed by Kteily et al.28, which assesses both support for “indirect” affirmative action (e.g., “Giving training to certain groups so they can compete equally”; r = 0.76), and “direct” affirmative action (e.g. “Using memberships in certain groups as a tie-breaker when applicants are equally qualified”; α = 0.89).

Study 2 Outcome

Support for Inequality-Reducing Policies. Support for policies designed to reduce racial inequality was measured using four items developed for this study (e.g. “The government should ensure that schools receive equal funding regardless of the racial makeup of the students” (α = 0.81).

Analytic strategy

General analytic strategy

Our primary analyses were conducted in three steps. First, using latent profile analysis (LPA), we determined the number and nature of the subgroups in each sample using the five identity-management strategies as profile indicators. Second, using multinominal regression, we tested theoretically derived predictions about which values predict membership in the profiles. Third, we examine the social and political outcomes of membership in each of the profiles by regressing our outcome variables on the posterior probabilities of membership in each profile (while setting the model’s intercept term to 0). This approach yields predicted values of the outcomes when the probability of membership in a given subgroup is 129,30,31. All significance tests are two-sided unless stated otherwise.

Model selection approach in latent profile analysis

As a form of mixture modeling, LPA is premised on the notion that variables’ observed distributions may reflect unobserved subgroups (“profiles”) of individuals32. The goals of LPA are to identify the number of distinct subgroups in the data and to characterize each subgroup in terms of the indicator variables. LPA bears similarities to other clustering techniques, such as cluster analysis and latent class analysis (LCA). However, unlike cluster analysis, LPA has the advantage of being model-based, with criteria for helping to select an optimal solution, though theoretical interpretability also plays an important role in selecting a profile solution30. To extract latent subgroups from the population, we tested LPA models that assume the “local independence” of the indicator variables (i.e., that profile membership explains all of the observed associations between indicators). Thus, our models constrained the residual (within-profile) covariances between indicators to zero. Additionally, the variances of each indicator were constrained to equality across profiles. We attempted to estimate models that loosened these constraints. Doing so, however, led to widespread convergence problems. We therefore elected to focus on more parsimonious model specifications. We used the tidyLPA package with Mplus Integration33 in R to test LPA solutions for our five indicator variables (Defend, Deny, Distance from Inequality, Distance from Identity, Dismantle). Models specifying from one to ten profiles were examined.

In choosing a solution, we first compared models with k profiles to those with k – 1 profiles using the bootstrapped likelihood-ratio test (BLRT) and Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin (VLMR) test. Significant values on both tests indicate that an additional profile adds explanatory power to the model. Second, following Nylund et al.’s34 recommendations, we compared the models using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC). In interpreting the BIC and AIC, smaller values suggest that more variance has been accounted for35. Third, we examined entropy values for each model. Entropy ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values representing better differentiation between the profiles. Values greater than .80 indicate clear delineation between profiles36. Lower values do not necessarily indicate misfit, but rather that the profiles are less distinguishable37. Finally, because comparison of overall fit and use of model-improvement tests cannot always be relied on to prevent overfitting38,39, model selection was informed by solutions’ theoretical interpretability30 and we rejected models with extremely small profiles40,41. In sum, we attempted to identify a well-fitting, theoretically useful, and parsimonious statistical solution—one that accurately reflects contours in the data without overfitting them by estimating more model parameters than necessary30,41,42.

Results

Step 1: Latent profile analysis

Table 1 presents fit statistics for the various profile solutions from both studies.

Study 1 model selection

In Study 1, the first model that failed to significantly improve fit according to the VLMR test was the three-profile model. However, because this test approached significance (p = 0.07), and because VLMR tests for the four-, five-, and six-profile solutions were significant (p’s < 0.008), we opted to examine these more complex solutions. The next model that failed the VLMR test was the seven-profile model. Therefore, we began by examining the six-profile solution.

Although the six-profile solution yielded a lower AIC and BIC and fit the data significantly better than the five-profile solution, inspection of the output revealed that one profile contained only 39 people (3% of the sample) scoring near the scale maximum on all indicators. Given that some indicators were strongly negatively correlated in the full sample, this profile likely reflected inattention or response set rather than a theoretically valid identity-management type. We therefore turned to the five-profile solution.

The five-profile solution had the next best AIC and BIC, provided significantly better fit to the data than did the four-profile model, and displayed an entropy value (0.83) indicating clear differentiation between the profiles. Inspection of the profiles revealed five theoretically interpretable subgroups, which we describe in detail below (see Fig. 2). Four of these profiles generally aligned with the original four predicted subgroups (i.e. Defenders, Deniers, Distancers, and Dismantlers), while a fifth appeared to deploy all the strategies to a similar degree.

Red dots represent the predicted scores on each indicator when the probability of membership in that profile is 1, and the probability of membership in the other profiles is 0, with 95% confidence intervals. Defender-Deniers (n = 86), Denier-Distancers (n = 221), Flexible-Ambivalents (n = 175), Distancers (n = 258), Dismantlers (n = 288).

Study 2 Model Selection

In Study 2, the first model to fail the VLMR test was the five-profile solution, though the test approached significance (p = 0.08). The next solution that did not increase fit relative to its corresponding k – 1 model was the seven-profile model (p = 0.27). Therefore, we elected to examine the four-, five-, and six-profile models and make a final decision based on the theoretical interpretability of the results30.

The four-profile solution largely replicated the four largest profiles found in Study 1—but did not reveal a profile characterized by a strong endorsement of the defend strategy. In contrast, the five-profile solution replicated all five profiles that emerged in Study 1 (see Fig. 3). The six-profile solution split a subgroup, found in the five-profile solution, characterized by high levels of denying (M = 5.41) and distancing from identity (M = 5.68) but moderately low levels of defending (M = 2.61), into two profiles that were the same on all other indicators but yielding one was low on defending (M = 1.95) and the another was moderately low (M = 3.87). We determined that the sixth profile failed to add theoretical value, and thus preferred the five-profile solution.

Red dots represent the predicted scores on each indicator when the probability of membership in that profile is 1, and the probability of membership in the other profiles is 0, with 95% confidence intervals. Defender-Deniers (n = 165), Denier-Distancers (n = 307), Flexible-Ambivalents (n = 388), Distancers (n = 436), Dismantlers (n = 324).

Multigroup LPA testing for invariance across samples

As a rigorous test of equivalence between the five-profile solutions in Studies 1 and 2, we conducted a multigroup LPA (though this analysis was not pre-registered). Multigroup LPA tests whether and to what degree LPA solutions are similar across samples in a manner analogous to invariance testing in confirmatory factor analysis. Multigroup LPA proceeds in four steps. First, a configural model is estimated in which a k-profile solution is estimated in both samples while freeing all parameters to vary between samples; this model serves as a baseline against which subsequent models are compared. Second, a structural invariance model is estimated in which each indicator’s mean is constrained to equality across samples, thus testing whether the profiles display the same pattern of means in both studies. Third, a dispersion invariance model is tested, in which each indicator’s variance is constrained to equality across samples, allowing us to test whether the variances around the mean are similar in both samples. Finally, distributional invariance constrains the sizes of each profile to be equal across samples, thus assessing whether the relative sizes of the latent profiles are similar in each study.

While no analog to the BLRT or VLMR is available for comparing multigroup LPA solutions, studies suggest that relative fit can be assessed using the CAIC, BIC, and SA-BIC40,43. In our data, the CAIC decreased as constraints were added to the model, indicating improvement in goodness-of-fit. Similarly, the BIC generally decreased as constraints were added to the model, indicating improvement in goodness-of-fit, with the lowest value being the distributional invariance model, though there was a very slight increase when moving from the configural to structural model. However, the SA-BIC increased very slightly (ΔSA-BIC < 80). The small size of these decrements in fit combined with the fact that the other indicators supported increasing fit, along with visual inspection of profile means and their distributions (see Figs. 2, 3), led us to conclude that the models exhibited structural, dispersion, and distributional invariance.

Below we describe each of the five profiles both in terms of their scores on the indicators used in the LPA, i.e. the different identity management strategies (for an overview see Fig. 2), and in terms of demographics. We examined demographic characteristics for each profile by regressing the posterior probabilities onto all the demographics. This gives us the predicted score (for continuous variables) or the predicted likelihood of being in a certain category (for categorical variables) for someone who has 100% probability of being in a given profile. We give a brief summary of selected demographics here (based on Study 2 data as this was the representative sample), and present full demographic information on each profile for both studies in the supplementary materials (see Study 1 and 2 supplemental results). Based on feedback we received on a draft of this manuscript, we also examined how these groups differ on a measure of white identification in a non-pre-registered analysis (see Supplementary note 1), finding that most of the profiles (3 out of 5) did not significantly differ from each other on this measure. This suggests that these profiles are picking up qualitative differences that are not captured simply by levels of white identification.

The profiles

Defender-Deniers

Defender-Deniers made up 8% of the Study 1 sample and 10% of the Study 2 sample. These white Americans are characterized by high levels of the defend and deny strategies—and very low levels of the dismantle strategy. In fact, all members of this profile are at or above the midpoint on the defend and deny and at or below the midpoint on dismantle. While Defender-Deniers tended to score above the midpoint on the two forms of distancing, we see high dispersion around these means and notice that the subgroup’s distancing scores are similar to those in other profiles—thus indicating that distancing is not a distinguishing feature of this profile. Members of this subgroup of white Americans believe that any inequalities between white and Black Americans are legitimate, while also minimizing the extent of those inequalities. A person most characteristic of the Defender-Denier profile was most likely to be male (67%), aged 54, very conservative (4.01 on a 1–5 scale), and a Republican (76%). In terms of religious identity, they were most likely to identify as Protestant/Just Christian (51%) or Catholic (18%). They were not likely to have earned a college degree (25%) and were estimated to earn around $53,000 per year.

Denier-Distancers

Denier-Distancers comprised 21% of the Study 1 sample and 19% of the Study 2 sample. These white Americans are characterized by high levels of the deny and distancing from identity strategies: All members of this profile are at or above the midpoint on deny and tend to score very high on distancing from identity, although a few cases dip below the midpoint. Although Denier-Distancers are almost as low on dismantling as are Defender-Deniers, Denier-Distancers tend not to defend racial inequality. This subgroup of white Americans asserts that racial inequality is minimal or nonexistent and prefers to avoid thinking about themselves in racial terms. In terms of demographics, the person most characteristic of the Denier-Distancer profile was most likely to be male (54%), aged 54, conservative (3.88 on a 1–5 scale), and a Republican (76%). In terms of religious identity, they were most likely to identify as Protestant/Just Christian (67%) but had a higher likelihood of being “None/Other” (20%) than the Defender-Deniers. They were not likely to have earned a college degree (37%) and were estimated to earn around $57,000 per year.

Distancers

Distancers made up 25% of the Study 1 sample and 26% of the Study 2 sample. These white Americans are characterized by high levels of the two distancing strategies. Indeed, these white people distance from identity and inequality more than all other strategies. Distancers score low on defend and deny but display middling levels of and high variance on the dismantling strategy. These white Americans acknowledge that there is racial inequality and that it is illegitimate—but they do not regard it as highly self-relevant. Demographically speaking, A person most characteristic of the Distancer profile was most likely to be female (52%) aged 52, moderately liberal (2.78 on a 1–5 scale), and a Democrat (63%). In terms of religious identity, this was one of the most religiously diverse groups, with a moderate likelihood of being Protestant/Just Christian (38%), and a relatively equal likelihood of being Atheist/Agnostic (18%) or Catholic (17%) or None/Other (19%). They were relatively equally likely to have earned a college degree (47%) versus not (53%) and were estimated to earn around $54,000 per year.

Dismantlers

Dismantlers comprise 28% of Study 1 sample and 20% of Study 2 sample. These white Americans strongly endorse dismantling and display very low levels of the defend and deny strategies. Dismantlers also distance from identity to a moderate extent; however, they do so less than all other profiles and display high variance on this indicator, suggesting that distancing from identity is not a defining feature of this subgroup. In general, these white Americans acknowledge that racial inequality exists, is illegitimate, and should be confronted—while also regarding it as self-relevant. The person most characteristic of the Dismantler profile was mostly female (58%), aged 47, liberal (1.75 on a 1–5 scale), and a Democrat (96%). In terms of religious identity, this was one of the least religious groups, with moderate likelihood of being Atheist/Agnostic (41%) and an equal likelihood of being None/Other (21%) or Protestant/Just Christian (21%). They were very likely to have earned a college degree (70%) and were estimated to earn around $73,000 per year.

Flexible-Ambivalents

This subgroup makes up 17% of the Study 1 sample and 24% of the Study 2 sample. These white Americans appear ambivalent in their stances regarding inequality and endorse most of the identity-management strategies to some extent. That said, Flexible-Ambivalents deploy the distancing significantly more than the other strategies, which may comport with their general ambivalence. When comparing the levels of the different strategies within the Flexible-Ambivalent profile, these white Americans endorse dismantling significantly less than they do all other strategies, suggesting that they lack a strong commitment to equality. We suspect that these white Americans lack strong ideological commitments and thus may deploy any strategy that is most effective in a given situation. A person most characteristic of this profile was most likely to be to be male (54%), aged 51, moderately conservative (3.40 on a 1–5 scale), and a Republican (54%). This group was highly likely to be Christian: Protestant/Just Christian (49%) or Catholic (24%). They were very unlikely to have earned a college degree (30%) and were estimated to earn around $48,000 per year.

Step 2: testing links between subgroup membership and underlying values

Having uncovered a consistent set of five white identity management profiles in two independent samples, we proceeded to test our predictions concerning links between subgroup membership and white Americans’ underlying social values5,8. Specifically, we examined how hierarchy, meritocracy, and egalitarianism values relate to the probability of membership in each of the five subgroups. In three multinomial logistic regression analyses, we regressed profile membership (coded as a nominal variable) on a value while weighting the observations by the corresponding profile frequency—thus accounting for the subgroups’ differing base rates. We then calculated the predicted change in profile membership probability when moving from low levels (i.e., the 16th percentile) to high levels (i.e., the 84th percentile) of the value, testing the significance of this change relative to 0. We chose this approach because the coefficients generated by our multinomial logistic regressions are expressed in terms of the relative probability of belonging to one profile versus another omitted baseline category. As such, the coefficients do not provide a global estimate of the relationship between a value and the probability of belonging to a specific profile. Examining the predicted change in membership likelihood for each profile as a function of value endorsement captures the overall value–profile link44.

For a summary of our predictions versus the observed effects in Studies 1 and 2, see Fig. 4. We did not begin this project with predictions concerning the Flexible-Ambivalent profile. Nonetheless, in keeping with this subgroup’s roughly equal endorsement of every strategy, we developed the expectation that membership in the Flexible-Ambivalent profile might vary somewhat as a function of all three values. Overall, 13 of our 15 effects were in the predicted direction and 11 were of the predicted size—providing generally strong support for the 4-D model of advantaged identity management. We next describe in detail the results of our multinomial logistic models.

Valuing hierarchy was strongly linked to profile membership in both Study 1 (χ2(3) = 1342.21, p < 0.001, McFadden’s Pseudo-r2 = 0.20) and Study 2 (χ2(4) = 2948.2, p < 0.001, McFadden’s Pseudo-r2 = 0.11). Participants high (vs. low) in SDO were significantly more likely to be Defender-Deniers and significantly less likely to be Dismantlers. Membership in the Distancer profile was most likely when SDO was relatively low, and membership in the Denier-Distancer and Flexible-Ambivalent profiles was most likely when SDO was moderate (see Fig. 5).

Meritocratic values were strongly linked to profile membership in Study 1 (χ2(4) = 2479.3, p < 0.001, McFadden’s Pseudo-r2 = 0.22) and Study 2 (χ2(4) = 4267.5, p < 0.001, McFadden’s Pseudo-r2 = 0.16). Participants high (vs. low) in support for meritocracy were significantly more likely to be Defender-Deniers and Denier-Distancers, and significantly less likely to be Dismantlers. Membership in the Distancer and Flexible-Ambivalent profiles was most likely when support for meritocracy was moderate to high (see Fig. 6).

Egalitarian values were strongly linked to profile membership in Study 1 χ2(4) = 1671.8, p < 0.001, McFadden’s Pseudo-r2 = 0.15) and Study 2 (χ2(4) = 1967.1, p < 0.001, McFadden’s Pseudo-r2 = 0.08). Participants high (vs. low) in universalism were significantly more likely to be Dismantlers and significantly less likely to be Defender-Deniers. Membership in the Flexible-Ambivalent profile was most likely when universalism was moderate. Membership in the Distancer profile also tended to increase with universalism, though not to the same extent as did membership in the Dismantler profile. The only profile that showed a different pattern between Study 1 and Study 2 was the Denier-Distancers. This inconsistency when levels of universalism are low may reflect imprecision due to very few people scoring on the low end of the scale for this value. When the effects of universalism are expressed in terms of changes in the probability of membership between the 16th to 84th universalism percentiles (which is less affected by skew), a more consistent pattern emerges (see Fig. 7).

Step 3: Outcomes of profile membership

We turn next to the outcomes of profile membership. Study 1 included a large number of outcome measures, of which we present a selection in the main text; the complete set of results can be found in the supplementary materials. Study 2 included only a single short measure of social-change attitudes due to limitations in the length of the TESS survey. Recall that this measure was preceded by an experimental manipulation in which participants saw an infographic (found in the supplementary materials) that framed racial inequality in terms of advantages experienced by white people or disadvantages experienced by Black people.

In Study 1, we observed large differences between most profiles on every outcome variable (see Fig. 8; for more detailed results see the supplementary materials). Although the Flexible-Ambivalent profile sometimes overlapped with the Denier-Distancer or the Distancer profiles, the results tended to confirm the hypothesized differences between the four main profiles on all outcomes. Specifically, Defender-Deniers were the group most likely to reject the principle of equality. Although Defender-Deniers’ support for the principle of equality was significantly lower than that of any other subgroup, their scores were still high in absolute terms—perhaps reflecting strong norms against the explicit rejection of equality. Defender-Deniers were also strongly opposed to policies implementing equality, including affirmative action, and more supportive than any other group of voting restrictions that would disproportionately affect minority voters.

Denier-Distancers generally resembled the Defender-Deniers in their attitudes toward social change—except in their higher support for the principle of equality, more moderate opposition to policies implementing equality, and weaker support for voting restrictions. Distancers strongly supported the principle of equality while still exhibiting a principle-implementation gap consistent with their theorized lack of enthusiasm for social change. Consistent with this, Distancers tended to support indirect affirmative action (e.g., providing trainings) but opposed direct affirmative action (e.g., using race as a tie-breaker in hiring). Distancers’ opposition to social change tended to be passive, however, as they opposed actively curtailing social change through the implementation of voting restrictions. Dismantlers were the only group to exhibit almost no principle-implementation gap, to strongly support both indirect and direct affirmative action, and to oppose voting restrictions. As might be expected, the Flexible-Ambivalent group tended to score near the midpoint of the scale or the middle of the distribution of the scores of the other groups on our outcome measures.

In Study 2, we also tested whether a type of framing manipulation known to increase support for action to combat economic inequality19 might also increase support for action to reduce racial equality—at least among some groups of white Americans. However, we observed no statistically significant overall effect of the framing manipulation, nor any statistically significant effect within any specific identity-management profile (see Table 2, Fig. 9). Despite this, we were able to use the outcome measure of support for inequality-advancing policies to again test our hypotheses regarding different profiles’ stances toward social change. The results generally supported our hypotheses, with Defender-Deniers displaying the strongest opposition to these policies, followed by Denier-Distancers, Flexible-Ambivalents, Distancers, and finally Dismantlers (who were highly supportive of such policies all differences were significant p < .001; see details in Supplementary Materials).

Red points are estimated values based on regression with the posterior class probabilities, such that they reflect the estimated value for a person who has a 100% probability of being in a given class and a 0% probability of being in any of the other classes. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. Defender-Deniers (Advantage n = 78; Disadvantage n = 87), Denier-Distancers (Advantage n = 153; Disadvantage n = 154), Flexible-Ambivalents (Advantage n = 191; Disadvantage n = 187), Distancers (Advantage n = 223; Disadvantage n = 213), Dismantlers (Advantage n = 155; Disadvantage n = 169).

General discussion

The present research found strong support for the 4-D model and its underlying theory. Overall, the observed identity management profiles of white Americans aligned with our theory, showing at least one profile characterized by each of the four primary identity-management strategies (i.e., defend, deny, distance, and dismantle). We also found a fifth profile whose members endorsed all strategies to some degree. Moreover, 13 of our 15 preregistered predictions concerning how values would predict membership in the identity-management subgroups were supported across both studies. As theorized, hierarchy values predicted membership in profiles with high levels of defend or deny (i.e., Defend-Deniers and Denier-Distancers), meritocratic values predicted membership in profiles with high levels of deny or distance (i.e., Denier-Distancers and Distancers), and egalitarian values predicted membership in profiles with high levels of distancing or dismantling (i.e. Distancers and Dismantlers). Finally, the emergent subgroups of white Americans differed in theorized ways in their stances toward social change: Specifically, Defender-Deniers were most strongly and actively opposed to change, Denier-Distancers were moderately opposed, Distancers neither actively opposed nor supported social change, and Dismantlers strongly supported change.

However, some results were unexpected. First, a fifth profile emerged that was characterized by the use of all identity management strategies. While not anticipated, this does not contradict the model, which sees the strategies as ways of reducing identity threat from conflicts between one’s values and one’s advantaged position in the racial hierarchy. The model does not preclude the possibility that some people may hold many values and thus deploy the strategies relatively flexibly. This may also reflect a general sense of obliviousness, or lack of sophistication when thinking about racial issues which has been discussed in the white identity content literature12,13. In other words, these participants may exhibit mixed responses because they have not previously given their racial identity and its consequences much thought.

Second, the four anticipated profiles were not as neat as expected. The Defender profile also exhibited high levels of the deny strategy, and the Denier profile showed high levels of the distance strategy. It is important to note, however, that this pattern does not contradict the 4-D model, which links both defend and deny to the same conjunction of threat and value—that is, status threat stemming from valuing hierarchy. Likewise, deny and distance are both seen as addressing meritocratic threat5,8. The observed overlap makes sense given these commonalities between pairs of identity-management strategies.

Third, the most significant deviation from theory was that meritocracy most strongly predicted membership in the Defender-Denier profile despite our prediction that this relationship would be null. This unexpected finding may reflect that the Defender-Denier profile, though uniquely high in the defend strategy, also exhibited high levels of the deny strategy and moderate levels of the distance strategy—both of which are theoretically linked to meritocracy. It may be that no coherent subgroup of white Americans values hierarchy to the exclusion of meritocracy. While a deviation from our predictions, this highlights the value of a person-centered approach. A variable-centered approach might reveal a stronger correlation between defend and hierarchy values than meritocracy, suggesting that people high on Defend value hierarchy over meritocracy. But by taking a person-centered approach, we find that no such group of people exists. Rather people very high on defend value both hierarchy and meritocracy, and thus are not uniquely high on defend but are also high on deny.

Finally, the framing intervention did not produce any meaningful effects. This may indicate that while framing inequality as an advantage rather than disadvantage may be effective in other domains19, it is not applicable to the racial context, though further research is needed to confirm and explain why this is the case. That being said, we did not expect the framing intervention to be effective for Defender-Deniers or Denier-Distancers, so the lack of effect here was not entirely unanticipated. Further, one of the groups where we did expect an effect, Dismantlers, had such high values on the outcome measure that this ceiling effect may have presented us from detecting an effect. While this study does not offer guidance for interventions, the results do indicate certain forms of white identity management can undergird significant opposition to social change, so additional work is needed to identify interventions that can effectively address this.

Limitations and future directions

While our findings support the 4-D model of advantaged identity management, our studies have limitations. First, we did not measure the threats specified in the theory (i.e., status threat, meritocratic threat, and moral image threat). These threats provide the link between values and identity management strategies, and our ongoing research seeks to document them. Second, the data are correlational, so we cannot say with certainty that the values cause profile membership. Future work should manipulate the salience of different values or the threats linked to them to examine the effect on identity-management strategies18. Third, it is unclear how these patterns of identity management develop and how stable they are over time. While observing similar profiles in two independent samples at two different points in time suggests some stability, people may adjust strategies based on situational demands. Future experimental work should directly manipulate and measure the threats specified by this theory to test their causal links to the strategies and examine the stability of identity-management profiles. Relatedly, chronic use of identity management profiles may consolidate into a certain white identity content12,13,14, and thus might be able to provide a measure for different forms of white identity content, for which adequate measures are lacking. So future research should investigate the relationship between chronic use of these strategies and white identity content.

Conclusion

This research uncovers subgroups among white Americans based on their management of white identity. In doing so, we demonstrate that both the nature of these groups and how values predict membership in them align with the current model of advantaged identity management5,8. Further, we demonstrate that how white Americans manage their identity has significant consequences for their stances on social change toward racial equality. Taken together, our work underscores the importance of understanding of advantaged identity management to promote a more equal society.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data are publicly accessible at https://osf.io/xgh9c/.

Code availability

The materials, preregistrations, and code for all analyses are publicly accessible at https://osf.io/xgh9c/

References

Craig, M. A. & Richeson, J. A. On the precipice of a “Majority-Minority” America: Perceived status threat from the racial demographic shift affects white Americans’ political ideology. Psychol. Sci. 25, 1189–1197 (2014).

Buchanan, L., Quoctrung, B. & Patel, J. Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in U.S. History. The New York Times (2020).

The White House. Executive Order On Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government. (2021).

Ellis, N. Florida’s new standards on Black history curriculum are creating outrage. CNN, (2023).

Knowles, E. D., Lowery, B. S., Chow, R. M. & Unzueta, M. M. Deny, distance, or dismantle? How White Americans manage a privileged identity. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9, 594–609 (2014).

Haslam, S. A. Psychology in Organizations: The Social Identity Approach. (Sage, London, 2001).

Leach, C. W., Snider, N. & Iyer, A. ‘Poisoning the Consciences of the Fortunate’: The Experience of Relative Advantage and Support for Social Equality. In Relative Deprivation: Specification, Development, and Integration (eds. Walker, I. & Smith, H. J.) (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK, 2002).

Shuman, E., Van Zomeren, M., Saguy, T., Knowles, E. & Halperin, E. Defend, deny, distance, and dismantle: a new measure of advantaged identity management. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672231216769 (2024).

Blanz, M., Mummendey, A., Mielke, R. & Klink, A. Responding to negative social identity: a taxonomy of identity management strategies. Eur. J. Soc. Psych. 28, 697–729 (1998).

Tajfel, H. & Turner, J. C. An integrative theory of group conflict. in The social psychology of intergroup relations (eds. Austin, W. G. & Worchel, S.) 7–24 (Nelson-Hall, Chicago, IL, 1979).

Phillips, L. T. & Lowery, B. S. Herd invisibility: the psychology of racial privilege. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 27, 156–162 (2018).

Goren, M. J. & Plaut, V. C. Identity form matters: white racial identity and attitudes toward diversity. Self Identity 11, 237–254 (2012).

Goren, M. & Plaut, V. Racial identity denial and its discontents: Implications for individuals and organizations. In K. M. Thomas, V. C. Plaut, & N. M. Tran (Eds.), Diversity ideologies in organizations. in Diversity ideologies in organizations (eds. Thomas, K., Plaut, V. & Tran, N.) 43–66 (Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2014).

Yantis, C. The role of White identity in anti‐racist allyship. Soc. Personal. Psych. 18, e70005 (2024).

Lizzio-Wilson, M. et al. How collective-action failure shapes group heterogeneity and engagement in conventional and radical action over time. Psychol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620970562 (2021).

Knowles, E. D. & Lowery, B. S. Meritocracy, self-concerns, and whites’ denial of racial inequity. Self Identity 11, 202–222 (2012).

Apfelbaum, E. P., Pauker, K., Sommers, S. R. & Ambady, N. In blind pursuit of racial equality? Psychol. Sci. 21, 1587–1592 (2010).

Lowery, B. S., Chow, R. M., Knowles, E. D. & Unzueta, M. M. Paying for positive group esteem: How inequity frames affect whites’ responses to redistributive policies. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 102, 323–336 (2012).

Dietze, P. & Craig, M. A. Framing economic inequality and policy as group disadvantages (versus group advantages) spurs support for action. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 349–360 (2020).

Annonymous. Defend, Deny, Distance, and Dismantle: A Measure of How Advantaged Group Members Manage Their Identity. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8190714 (2022).

Curran, P. J. & Hussong, A. M. Integrative data analysis: The simultaneous analysis of multiple data sets. Psychol. Methods 14, 81–100 (2009).

Dziak, J. J., Lanza, S. T. & Tan, X. Effect size, statistical power, and sample size requirements for the bootstrap likelihood ratio test in latent class analysis. Struct. Equ. Modeling: A Multidiscip. J. 21, 534–552 (2014).

Ho, A. K. et al. The Nature of Social Dominance Orientation: Theorizing and Measuring Preferences for Intergroup Inequality Using the New SDO7 Scale. 26 (2017).

Major, B., Kaiser, C. R., O’Brien, L. T. & McCoy, S. K. Perceived discrimination as worldview threat or worldview confirmation: Implications for self-esteem. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 92, 1068–1086 (2007).

Davey, L. M., Bobocel, D. R., Hing, L. S. S. & Zanna, M. P. Preference for the Merit Principle Scale: An Individual Difference Measure of Distributive Justice Preferences. 18 (1999).

Schwartz, S. H. & Boehnke, K. Evaluating the structure of human values with confirmatory factor analysis. J. Res. Personal. 38, 230–255 (2004).

Tuch, S. A. & Hughes, M. Whites’ racial policy attitudes. Soc. Sci. Q. 77, 723–745 (1996).

Kteily, N. S., Sheehy-Skeffington, J. & Ho, A. K. Hierarchy in the eye of the beholder: (Anti-)egalitarianism shapes perceived levels of social inequality. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 112, 136–159 (2017).

Knowles, E. D., McDermott, M. & Richeson, J. A. Varieties of White Working-Class Identity. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations (2024).

Pastor, D. A., Barron, K. E., Miller, B. J. & Davis, S. L. A latent profile analysis of college students’ achievement goal orientation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 32, 8–47 (2007).

Rivera Pichardo, E. J., Vargas Salfate, S. & Knowles, E. D. The psychology of colonial ideologies: Decoupling pro‐egalitarian and neo‐colonial sources of support for Puerto Rico statehood. British J Social Psychol .(2022) https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12591.

Oberski, D. Mixture Models: Latent Profile and Latent Class Analysis. In Modern Statistical Methods for HCI (eds. Robertson, J. & Kaptein, M.) 275–287 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26633-6_12.

Rosenberg, J., Beymer, P., Anderson, D., Van Lissa, C. J. & Schmidt, J. tidyLPA: An R Package to easily carry out Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) using open-source or commercial software. JOSS 3, 978 (2018).

Nylund, K. Latent transition analysis:Modeling extensions and anapplication to peer victimization. (University of California, Los Angeles., 2007).

Posada, D. & Buckley, T. R. Model selection and model averaging in phylogenetics: advantages of akaike information criterion and bayesian approaches over likelihood ratio tests. Syst. Biol. 53, 793–808 (2004).

Magidson, J. & Vermunt, J. Latent class models. In The SAGE Handbook of Quantitative Methodology for the Social Sciences (2004).

Celeux, G. & Soromenho, G. An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. J. Classif. 13, 195–212 (1996).

Ferguson, S. L., G. Moore, E. W. & Hull, D. M. Finding latent groups in observed data: A primer on latent profile analysis in Mplus for applied researchers. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 44, 458–468 (2020).

Masyn, K. E. Latent Class Analysis and Finite Mixture Modeling. (Oxford University Press, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199934898.013.0025.

Lubke, G. & Neale, M. C. Distinguishing between latent classes and continuous factors: resolution by maximum likelihood? Multivar. Behav. Res. 41, 499–532 (2006).

Spurk, D., Hirschi, A., Wang, M., Valero, D. & Kauffeld, S. Latent profile analysis: A review and “how to” guide of its application within vocational behavior research. J. Vocation. Behav. 120, 103445 (2020).

Weller, B. E., Bowen, N. K. & Faubert, S. J. Latent class analysis: a guide to best practice. J. Black Psychol. 46, 287–311 (2020).

Petras, H. & Masyn, K. General growth mixture analysis with antecedents and consequences of change. in Handbook of Quantitative Criminology (eds. Piquero, A. R. & Weisburd, D.) 69–100 (Springer New York, New York, NY, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-77650-7.

Hanmer, M. J. & Ozan Kalkan, K. Behind the curve: clarifying the best approach to calculating predicted probabilities and marginal effects from limited dependent variable models. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 57, 263–277 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported a Binational Science Foundation grant [2020013] to the final two authors. The Binational Science Foundation had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. This work was also support supported by a Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences (TESS) Award to the first author. TESS reviewers reviewed the study design but no changes to study design were made based on their recommendations. TESS paid for NORC Amerispeak to collect the data for Study 2. Other than this, TESS had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Eric Shuman: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Data curation; Formal analysis; Project administration; Resources; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. Eran Halperin: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Writing—review & editing. Eric Knowles: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Psychology thanks Nils Karl Reimer and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Marike Schiffer. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shuman, E., Halperin, E. & Knowles, E. Advantaged identity management strategies differentiate five subgroups of white Americans. Commun Psychol 3, 58 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00239-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-025-00239-0