Abstract

Well-being is commonly defined in terms of comfort, happiness, functioning, and flourishing. Scholars distinguish between subjective well-being (i.e., perceiving life as pleasant) and psychological well-being (i.e., perceiving life as meaningful). While advances in natural language processing have enabled automated assessments of subjective well-being from language, their ability to capture psychological well-being remains underexplored. Across three studies (one preregistered), we examined how well language-based models predict self-reported subjective and psychological well-being. Participants provided verbal or written responses about their satisfaction with life and autonomy, along with standard questionnaire measures. We used contextual word embeddings from transformer-based models to predict well-being scores. Language-based predictions correlated moderately with questionnaire measures of both constructs (rs = .16–.63) and generalized across well-being domains (rs = .15–.50), though these associations were weaker than previously work (rs = .72–.85). Autonomy was consistently less predictable than satisfaction with life. Comparisons with GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 revealed that both models outperformed BERT in predicting satisfaction with life (r = .71 and .75) and modestly improved predictions of autonomy (rGPT‑4 = .49). Supervised dimension projections revealed that satisfaction with life responses clustered around positive emotion and social themes, whereas autonomy responses showed more individualized linguistic patterns. These findings suggest that language-based tools are well-suited for assessing hedonic well-being but face challenges with more abstract, eudaimonic constructs. Future research should refine modeling approaches to enhance the detection of complex psychological states while striking a balance between interpretability, accuracy, and usability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Well-being is central to human functioning and flourishing and it has been linked to effective learning, creativity, prosocial behavior, and positive relationships1,2,3. Thus, accurately measuring well-being is crucial for understanding, predicting, and promoting psychological health in individuals and groups4.

Scholars have shown a growing interest in the development of tools to evaluate well-being and ill-being using language5,6,7. Language provides a natural means for people to express their states of mind, making language a suitable window for understanding well-being and how an individual evaluates their life8. Specifically, language-based assessments may capture an individual’s appraisal of their quality of life more richly and idiosyncratically than the constrained limits of close-ended questionnaire measures6. Such linguistic measures can unobtrusively detect an individual’s internal experiences, offering researchers a nuanced, context-rich approach to understanding the complexities of human psychological states and their fluctuations over time.

Previous research has demonstrated the promise of integrating computational linguistics and psychological theory to assess psychological states and traits9,10,11,12. For example, linguistic measures can be used to track changes in relationship health13, life satisfaction14, psychopathology15,16,17,18, and emotion19. Recent advancements in deep learning have enhanced the automated assessments of psychological constructs using Large Language Models (LLMs). Indeed, Artificial Intelligence (AI)-based language analysis of open-ended survey responses can generate remarkably accurate estimates of questionnaire-based measures14. The stage is set to refine tools that capture language meaning and reveal the person behind the words.

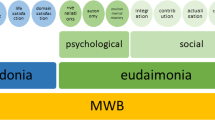

However, language-based assessments have mostly focused on just one facet of well-being: subjective well-being. Well-being can be decomposed into dimensions, namely subjective or hedonic well-being (i.e., perceiving one’s life as pleasant) and eudaimonic or psychological well-being (i.e., perceiving one’s life as meaningful)8. Further, these dimensions each have underlying components that are interrelated and support their underlying structure20,21,22,23. Subjective well-being is characterized by the experience of high levels of positive emotions, low levels of negative emotions, and high satisfaction with life24. Whereas, psychological well-being frequently includes six components: autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance25.

The language-based assessment of psychological well-being and its components remains largely unexplored, raising questions about its effectiveness compared to assessments of subjective well-being. For instance, a higher frequency of emotion words may capture the experience of subjective well-being, as prior research has demonstrated a link between the use of such words and the experience of emotional states26. Conversely, language reflecting psychological well-being may be harder to assess, as it often involves abstract, subjective, and idiosyncratic concepts like goal pursuit, purpose in life, and personal growth. Therefore, testing whether language-based assessments can measure psychological well-being as effectively as subjective well-being, and whether they generalize to other components, can clarify the strengths and limitations of these methods.

We extend prior work on language‑based well‑being assessment by asking: can language‑derived measures predict survey‑based psychological well‑being, and how does this compare to the prediction of subjective well‑being1,24,25,27? Across three studies, we applied contextual word embeddings, following the approach from Kjell et al.14, to predict scores on the Ryff Psychological Well‑Being Scale25,28 and the Satisfaction with Life Scale27, then compared predicted vs. observed scores to evaluate model performance. In Study 3, we also benchmarked our models against modern generative models (e.g., GPT-3.5 and GPT-4) to determine which yields better automated well‑being assessments.

Methods

Open science statement

All studies were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided informed consent. Data needed to reproduce our main findings are available at: https://github.com/cnlab/LP2-wellbeing-prediction/tree/main/data, and analysis code is available at: https://github.com/cnlab/LP2-wellbeing-prediction. Studies 1 and 2 were not preregistered. Study 3’s design, hypotheses, and primary analyses were preregistered on July 15, 2024, at https://osf.io/qac8j/?view_only=fa6a39b16a1c43a4afa2fb81d5cccb28. Language visualizations, correlation comparisons, and LLM comparisons were conducted post hoc and therefore not preregistered. Individual demographics and open-ended responses are not publicly available to protect participant confidentiality.

Study 1

In Study 1, we were interested in whether language-based assessments of psychological well-being could converge self-reported psychological well-being and satisfaction with life. Participants completed narrative prompts designed to elicit reflections on six well-being components, including autonomy, self-acceptance, and purpose in life. We then analyzed these responses using contextual word embeddings to explore the extent to which patterns in language corresponded with standardized self-report measures.

Participants

Study 1 recruited 185 participants in July 2023 via Prolific Academic with the following inclusion criteria: U.S. residency, English fluency, no current psychiatric diagnosis, and a Prolific approval rating above 95%. Four individuals were excluded for not complying with study instructions (e.g., failing to respond in good faith to self-reflection prompts). The final sample (N = 181) ranged in age from 19 to 75 years (M = 41.73, SD = 15.05). Gender identities were self-reported as 49.72% men, 49.17% women, and 1.11% not reported. Racial and ethnic identities were self-reported as: White (75.14%), Black or African American (11.60%), East Asian (2.76%), Southeast Asian (2.21%), South Asian (1.10%), Multiracial (5.50%), and not listed (1.66%). Additionally, 8.29% identified as Hispanic or Latino.

Procedure

The parent study (https://osf.io/c8wzs) used a within-person design where participants experienced both a narrative self-reflection intervention and a control (no reflection) condition. After informed consent, participants completed a baseline survey covering mental health, well-being, and demographics, followed by instructions for the intervention. They then completed daily mental health and well-being surveys for 12 days. On intervention days, participants also completed an audio-recorded self-reflection task responding to three prompts adapted from validated scales (e.g., Ryff Psychological Well-Being Scale), speaking for 1–3 min per prompt. Six prompt sets were counterbalanced via a Latin Square design and presented in varied order across participants. Attention checks (e.g., “Select ‘Strongly Agree’” and “Copy and paste this text”) were embedded to help promote data quality. Control days included daily surveys without reflection tasks. Conditions were grouped in 3-day blocks of either intervention or control. On day 14, participants completed a post-intervention survey with the same outcome measures and user experience questions, and were debriefed and compensated. Participants received $5 for the baseline survey (Day 1), $2 for each of 12 daily surveys (Days 2–13), and $3 for the final survey (Day 14), with a $5 bonus for completing at least 10 of 12 daily surveys, for a maximum compensation of $36. Primary analyses focus on baseline closed-ended responses and open-ended reflection responses from intervention days; follow-up survey analyses are in the Supplemental Information (See Figs. S1 and S3).

Instruments

Close-ended self-report

Participants’ subjective well-being was measured using the 5-item Satisfaction with Life Scale27, which showed excellent reliability (Cronbach’s α = 93; McDonald’s ω = 93). Psychological well-being was assessed with the 18-item Ryff Psychological Well-Being Scale28, comprising six subscales: Autonomy, Environmental Mastery, Personal Growth, Positive Relations, Purpose in Life, and Self-Acceptance, each scored as the mean of its items. The scale showed good reliability overall (α = 81; ω = 88). Mean scores across subscales were averaged for an overall psychological well-being score. Subscale reliabilities are in Table S2; correlations among measures appear in Table S3.

Language-based assessment

As part of the self-reflection task, participants reflected on six well-being components, and we developed three prompts to guide reflection across each of these six constructs (see Table 1 for a comprehensive list of prompts). Participants engaged with the same prompt type on a given day and completed each of the three prompts in succession (e.g., Autonomy 1, 2, and 3).

Analytic method

Analyses were conducted using the text R-package (v1.2.1)29. We first generated contextual word embeddings from transcribed self-reflections and then used these embeddings as features in ridge regression models to predict pre-intervention self-reported well-being scores. Results are reported as one-tailed Pearson correlations between predicted and observed scores (see Kjell et al.29 for more details). We focus on pre-intervention outcomes, as post-intervention results were similar (see Figs. S1 and S3).

Word embedding generation

Following past research14, we generated contextual word embeddings using bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT)-large-uncased30, a 24-layer transformer language model with 1,024 dimensions per layer. We extracted embeddings from the 23rd layer for each participant’s response, as this layer has shown strong performance in prior human-level prediction tasks31. We then concatenated embeddings across prompts for the same well-being component to create a single vector per construct using the textTrainRegression function in the text package29.

Cross-validated prediction of well-being ratings

Using the embeddings as features, we trained ridge regression models to predict self-reported well-being scores. Models were first trained to predict the same component (e.g., autonomy embeddings predicting autonomy scores), then cross-predicted other components (e.g., autonomy embeddings predicting life satisfaction). We used nested 10-fold cross-validation to obtain unbiased performance estimates. In each outer fold, 10% of the data was reserved as a test set. The remaining 90% was partitioned into training (75%) and validation (25%) subsets. Ridge regression penalties (ranging from 10⁻¹⁶ to 10¹⁶) were optimized via grid search, selecting the penalty that minimized root mean squared error (i.e., a measure of how far predictions are from actual values, on average) on the validation set. Using the optimal penalty, we retrained the model on the combined training and validation data (90%) and evaluated performance on the reserved test set (10%). All data splits were stratified by outcome quartiles to preserve distributional properties. We report one-tailed Pearson correlations between predicted and observed scores, with False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction applied for multiple comparisons32.

Transcription

All audio responses were transcribed using Phonic, an audio recording platform that utilizes Amazon Web Services’ speech-to-text technology to transcribe audio clips33. The first author reviewed transcriptions, and no manual edits or corrections were made to the transcripts following transcription.

Study 2

Building on Study 1, which showed modest correlations between language-based autonomy assessments and psychological well-being scores, Study 2 aimed to improve measurement by addressing design limitations. We collected spoken and written responses to prompts assessing autonomy (a high-performing component from Study 1) and satisfaction with life, to replicate past research14, administered language and self-report measures concurrently, and used prompts designed to elicit variance in responses (e.g, discussion of aspects a participant may [or may not] enjoy about themselves). We then examined how predictive accuracy varied by well-being type (autonomy vs. satisfaction with life), modality (audio vs. text), the language features associated with high vs. low well-being, and compared correlations between components of well-being and past literature.

Participants

Study 2 included 222 college students recruited between March and May 2024 via the SONA System at a private U.S. university with the following inclusion criteria: English fluency and no current psychiatric diagnosis. Participants were aged 18–23 years (M = 19.69, SD = 1.17). Gender identities were self-reported as 37.67% men, 60.47% women, 0.47% non-binary, and 1.40% unreported. Racial and ethnic identities were self-reported as White (44.44%), East Asian (16.20%), Black or African American (11.57%), South Asian (9.72%), Biracial (6.47%), Southeast Asian (2.31%), and American Indian or Alaska Native (0.46%). No participants were excluded.

Procedure

We conducted an experiment to compare language-based well-being assessments across spoken and written language. After providing consent, participants were randomly assigned to the Audio (N = 95) or Text condition (N = 127). All responded to two open-ended prompts assessing satisfaction with life (adapted from past research14) and autonomy (the best-performing item from Study 1), presented in randomized order. Participants then completed randomized questionnaire assessments of subjective and psychological well-being, rated the experience’s usefulness, provided user feedback, completed demographics, and exited the survey (see Fig. S5). Participants completed embedded attention checks throughout, including prompts such as “Select ‘Strongly Agree’ for this item” and “Copy and paste this text [TEXT] into the box,” and received 0.25 course credits upon completion.

Instruments

Close-ended self-report

We used the same self-report measures as Study 1. Participants’ subjective well-being was assessed with the Satisfaction with Life Scale, which demonstrated strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s ɑ = 0.86; McDonald’s ω = 0.86). Psychological well-being was assessed with the Ryff Psychological Well-Being scale, which demonstrated strong reliability (ɑ = 0.82; ω = 0.86). Subscale item reliabilities are reported in Table S6 and correlations between the measures of well-being are available in Table S8.

Language-based assessment

Participants answered two open-ended questions on satisfaction with life and autonomy, responding either in writing (at least one paragraph) or speech (at least 60 s), depending on random assignment to the Text or Audio condition (see Table 2).

Text analysis methods

We applied the same text analysis approach as Study 1. The first author reviewed transcriptions, and no manual edits or corrections were made to the transcripts following transcription.

Visualizing language‑based assessments of well-being

To identify words distinguishing high- from low-well-being responses, we used a supervised dimension projection approach29. Unlike unsupervised dimensionality reduction methods such as principal components analysis, this method identifies words in embedding space that best separate predefined groups, enabling us to focus specifically on the language features that track high vs. low well-being29. After tokenizing open-ended responses, removing Snowball stop words (i.e., a, and, the, etc.)34, and retaining tokens occurring at least five times, we passed the remaining tokens through BERT-large-uncased, extracted embeddings from the 23rd layer, and averaged embeddings to represent each response. Responses were then split into “low” and “high” groups based on the lower and upper quartiles of well-being scores (e.g., autonomy, life satisfaction; see Kjell et al.29 for a full overview). We then subtracted average embeddings of low from high groups to produce a direction vector capturing maximal variation between groups. Each word embedding was projected onto this vector by taking the dot product of the word embedding and the direction vector, where values near zero indicated no association and larger magnitudes indicated stronger relations with high or low well-being.

We assessed significance by comparing dot products to a null distribution from 10,000 permutations (i.e., randomized reshufflings of the group labels), with p values corrected for multiple comparisons using a FDR correction. Before visualization, we stemmed each token (e.g., collapsing “happy”/“happier”/“happiest” into the word “happy”), summed its frequency, and combined its multiple permutation‑based p values using Fisher’s method35, yielding one significance test per stem.

For visualization, we selected the top 100 significant stems (50 associated with high well-being, 50 with low) showing the strongest effect sizes for each well-being measure. We then analyzed these stems using LIWC-2236, weighting dictionary scores by stem frequency, and then rank-ordered the LIWC dictionaries by weighted frequency (see Fig. S11).

Transcription

We used the same audio transcription approach as Study 1. The first author reviewed transcriptions, and no manual edits or corrections were made to the transcripts following transcription.

Comparing accuracy by method

We assessed prediction accuracy by computing squared errors for models using text vs. audio input, then conducted Welch’s t-tests to evaluate differences between methods. All results were FDR-corrected for multiple comparisons.

Study 3

In Study 3, we aimed to replicate the findings from Study 2 in a fully powered, preregistered study using text-based well-being assessments of autonomy and satisfaction with life. We hypothesized that predictions generated from participants’ language-based assessments of satisfaction with life and autonomy would significantly converge with self-reported ratings of these components. We anticipated that the accuracy of satisfaction with life predictions would be higher than that for autonomy. Lastly, we compared the performance of our BERT-based models against current state-of-the-art LLMs that were less common when the original studies were conducted.

Power analysis

We conducted a power analysis, informed by Studies 1 and 2, and determined that at a minimum, we would require N = 255 to have 90% power, with an alpha of 0.05, to detect a small-to-medium effect size of r = 0.20 between the predicted and observed values. To account for potential data loss, we aimed to recruit 285 participants.

Participants

Study 3 recruited 285 participants in June 2024 via Prolific Academic with the following inclusion criteria: U.S. residency, English fluency, no current psychiatric diagnosis, and either a Prolific approval rating above 95%. Participants ranged from 18 to 79 years old (M = 38.16, SD = 12.28). Gender identities were self-reported as 48.07% men, 50.88% women, 0.70% non-binary, and 0.35% genderqueer. Racial and ethnic identities were self-reported as White (58.25%), Black or African American (27.02%), Multiracial (4.90%), East Asian (3.16%), Southeast Asian (1.75%), South Asian (1.05%), other/unlisted (2.81%), and 1.05% preferred not to say; 9.12% identified as Hispanic/Latino. No participants were excluded due to failed attention checks or data quality issues.

Procedure

The same procedure as in Study 2 was used here with the following exceptions. First, all participants provided written responses. Second, we altered the wording of the prompts from Study 2 based on user feedback to promote user engagement (see Table 3 for revised prompts). Upon survey completion, participants were compensated $3 for their time.

Instruments

Close-ended self-report

We used the same self-report measures as Studies 1–2. The Satisfaction with Life Scale showed excellent reliability (Cronbach’s ɑ = 0.92; McDonald’s ω = 0.92), and the Ryff Psychological Well-Being Scale demonstrated good reliability (ɑ = 0.83; ω = 0.85). Subscale reliabilities are in Table S10; correlations appear in Table S12.

Language-based assessments

Participants were instructed to write at least five sentences in response to open-ended questions assessing their satisfaction with life and autonomy.

Text analysis methods

The same text analysis approach described in Studies 1–2 was used in this study.

Visualizing language‑based assessments of well-being

The same word-embedding visualization technique described in Study 2 was used in this study.

GPT-based assessment

To benchmark our BERT-based language-based prediction models against current state-of-the-art LLMs, we evaluated Study 3 responses using OpenAI’s GPT-3.5-turbo-1106 and GPT-4. Results are reported as two-tailed Pearson correlations between predicted and observed scores.

Model querying

We queried the models using the OpenAI Application Programming Interface Python library and analyzed results in R. A temperature of 0 was used to ensure consistent, high-probability outputs. Analyses were conducted in June 2025.

Model prompting

Using the chat completion feature, we instructed GPT to rate open-ended responses along seven well-being dimensions (e.g., Autonomy, Satisfaction with life) on a 1–7 scale. Ratings were returned as JSON objects (see Table S13 for full prompt). Psychological well-being was computed as the mean of six components. All texts were evaluated with identical prompts, without few-shot examples or chain-of-thought reasoning. Autonomy and satisfaction responses were analyzed separately.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Study 1

To what degree do language‑based assessments of psychological well-being components converge with self-reports of these components?

We examined how well contextual embeddings from language-based assessments predicted self-reported scores of the same psychological well-being components (e.g., autonomy embeddings predicting autonomy). Predicted autonomy scores correlated moderately with self-reports (r(179) = 0.36, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.249, 1]), while associations for other well-being components were not significant (see Fig. 1).

Note. N = 181. Values are Pearson correlations, with disattenuated correlations in parentheses (adjusted to account for measurement unreliability, representing the estimated true correlation between constructs); 95%CIs and RMSE indicated in brackets. Columns are grouped by prompt type. RMSE reflects average prediction error; lower values indicate better model performance. P values were FDR-corrected for multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (FDR-corrected). Significant correlations are bolded. PWB Ryff Psychological Well-Being, PWB mean Overall PWB score, SWLS Satisfaction With Life Scale.

To what degree do language‑based assessments of psychological well-being components correlate with other components?

We next tested whether models trained on embeddings from language-based assessments of one well-being component correlated with other components. Estimates generated from autonomy models correlated weakly with self-reported environmental mastery (r(179) = 0.28, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.163, 1]), overall psychological well-being (r(179) = 0.21, p = 0.003, 95% CI [0.087, 1]), satisfaction with life (r(179) = 0.14, p = 0.03, 95% CI [0.017, 1]), and self-acceptance (r(179) = 0.14, p = 0.03, 95% CI [0.02, 1]). Predictions from models trained on positive affect embeddings correlated weakly with satisfaction with life (r(179) = 0.16, p = 0.02, 95% CI [0.038, 1]) and overall psychological well-being (r(179) = 0.15, p = 0.02, 95% CI [0.027, 1]). Models trained on other psychological well-being components did not significantly correlate with other components.

Comparisons with previous research

We also tested whether our observed correlations differed from those reported in prior work using Fisher’s r-to-z transformation with a z-test37. Our results showed that the correlation between language-based assessments of autonomy and self-reported autonomy in our sample (r = 0.36, N = 181) was significantly lower than the correlation reported by Kjell et al.14 (r = 0.74, N = 608) (z = –6.73, p < 0.001, 95% CI [–0.74, –0.41]) for language-based assessments of satisfaction with life.

Study 2

To what degree do language‑based assessments of satisfaction with life converge with self-reports?

We first assessed how well model predictions based on language‑based assessments of satisfaction with life responses correlated with self-reported well-being (see Fig. 2). We observed that predictions from language-based assessments of satisfaction with life were moderately correlated with survey ratings of satisfaction with life (r(213) = 0.43, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.339, 1]). Concerning cross-construct convergence, we found model predictions from language-based assessments of satisfaction with life correlated with self-reported levels of self-acceptance (r(213) = 0.29, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.187, 1]), environmental mastery (r(213) = 0.30, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.189, 1]), and overall psychological well-being (r(213) = 0.24, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.135, 1]).

Note. N = 222. Values are Pearson correlations, with disattenuated correlations in parentheses (adjusted to account for measurement unreliability, representing the estimated true correlation between constructs); 95%CIs and RMSE indicated in brackets. Columns are grouped by prompt type. RMSE reflects average prediction error; lower values indicate better model performance. P values were FDR-corrected for multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (FDR-corrected). Significant correlations are bolded. PWB Ryff Psychological Well-Being, PWB mean Overall PWB score, SWLS Satisfaction With Life Scale.

How does the performance of language-based assessments of autonomy compare to that of satisfaction with life?

In contrast to satisfaction with life, model predictions based on language‑based assessments of autonomy responses were weakly correlated with self-reported ratings of autonomy (r(213) = 0.16, p = 0.02, 95%CI [0.047, 1]) and were considerably smaller than those in Study 1. When examining generalizability, predictions from language-based assessments of autonomy were moderately correlated with participants’ self-reported ratings of positive relationships (r(213) = 0.21, p = 0.003, 95%CI [0.097, 1]), environmental mastery (r(213) = 0.25, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.146, 1]), and overall psychological well-being (r(213) = 0.26, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.149, 1]). Notably, some of these effect sizes are larger than that for self-reported autonomy, supposedly the same component as what the language prompt targeted.

Language features associated with well-being

Panel a of Fig. 3 shows the 100 words that best differentiate low- and high-autonomy responses. Low-autonomy participants used more tentative and cognitive processing words (e.g., maybe, guess), signaling uncertainty and problem-solving. High-autonomy participants also used cognitive words but favored insight- and goal-related action terms (e.g., deemed, goal), reflecting clarity and purposeful behavior. Panel B shows a similar pattern for satisfaction with life: low scorers used cognitive and function words (e.g., think, seem), indicating uncertainty, while high scorers used positive-emotion and social words (e.g., love, spouse), reflecting positive affect and relationships.

Note. Words significantly associated with low well-being (red) and high well-being autonomy (green) and satisfaction with life (blue) are displayed in the embedding space. a Shows words significantly associated with autonomy, and b shows words significantly associated with satisfaction with life. Font size reflects word frequency. The x-axis represents association strength (the dot product along the primary embedding dimension), with higher values indicating stronger associations with higher well-being. The y-axis is used only for visual separation and has no interpretive meaning.

Does accuracy differ as a function of response modality?

In comparing the accuracy of models trained on data across response modality (i.e., comparing squared errors for Audio [N = 95] or Text condition [N = 127]), results revealed no significant differences (See Tables 4–5). Post hoc sensitivity analyses suggest that, given the sample size and observed variability, the study was adequately powered to detect moderate differences in errors (Cohen’s d = 0.3–0.438), but underpowered to detect small effects. Given that our observed differences were small (Cohen’s d = 0.01–0.28), these results may reflect a false negative.

Comparing correlations

We also compared our observed correlations with those reported in Kjell et al.14 using Fisher’s r-to-z transformations with a z-test37. The correlation between our language-based assessment of life satisfaction and self-reported satisfaction with life (r = 0.44, N = 215) was significantly weaker than the correlation reported by Kjell et al. (r = 0.74, N = 608) (z = –5.99, p < .001, 95% CI [–0.64, –0.32]). Similarly, the correlation between our language-based assessment of autonomy and its corresponding self-report measure (r = 0.18, N = 215) was significantly lower than the value reported by Kjell et al.14 (z = –6.73, p < .001, 95% CI [–0.74, –0.41]).

Next, we compared the strength of correlations between autonomy and satisfaction with life within our own sample using Steiger’s Test (i.e., testing for a statistically significant difference between dependent correlations with different variables)39. The correlation between language-based satisfaction with life and self-reported satisfaction with life was significantly stronger than the correlation between language-based autonomy and self-reported autonomy (r = 0.44 vs r = 0.16; z = −9.887, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.738, −0.560].

Study 3

To what degree do language‑based assessments of satisfaction with life converge with self-reports?

Consistent with preregistered hypotheses, BERT-based predictions from satisfaction with life language‑based assessments strongly correlated with survey ratings (r(283) = 0.62, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.561, 1]; Fig. 4). These predictions were also moderately correlated with other well-being components such as self-acceptance (r(283) = 0.50, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.424, 1]), environmental mastery (r(283) = 0.44, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.358, 1]), overall psychological well-being (r(283) = 0.40, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.318, 1]), and purpose (r(283) = 0.22, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.129, 1]). However, they weakly correlated with positive relationships (r(283) = 0.15, p = 0.006, 95%CI [0.057, 1]), personal growth (r(283) = 0.12, p = 0.025, 95%CI [0.019, 1]), and autonomy (r(283) = 0.13. p = 0.016, 95%CI [0.034, 1]).

Note. N = 285. Values are Pearson correlations, with disattenuated correlations in parentheses (adjusted to account for measurement unreliability, representing the estimated true correlation between constructs); 95%CIs and RMSE indicated in brackets. Columns are grouped by prompt type. RMSE reflects average prediction error; lower values indicate better model performance. P values were FDR-corrected for multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (FDR-corrected). Significant correlations are bolded. PWB Ryff Psychological Well-Being, PWB mean Overall PWB score, SWLS Satisfaction With Life Scale.

How does the performance of language-based assessments of autonomy compare to that of satisfaction with life?

Predictions from BERT-based predictions from autonomy language‑based assessments were again less accurate than those from satisfaction with life prompts. These predictions were moderately correlated with participants’ survey ratings of autonomy (r(283) = 0.41, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.329, 1]) and weakly correlated with survey scores for satisfaction with life (r(283) = 0.21, p = 0.001, 95%CI [0.111, 1]), self-acceptance (r(283) = 0.18, p = 0.004, 95%CI [0.079, 1]), and environmental mastery scores (r(283) = 0.17, p = 0.004, 95%CI [0.073, 1]).

Language features associated with well-being

Figure 5a shows the top 100 words distinguishing low- vs. high-autonomy responses. Low-autonomy participants used more cognitive processing, affect, and function words (e.g., ensure, maintain, strike, evaluate), suggesting a focus on negative states. High-autonomy participants also used cognitive words, but alongside insight, social, and action-oriented terms (e.g., go, let, spend, care), reflecting agency and problem-solving. Figure 5b shows the analogous pattern for satisfaction with life: low-satisfaction responses included cognitive, function, and tentative words (e.g., think, seem, sometimes), indicating uncertainty and negative experiences. High-satisfaction responses featured positive-emotion and social words (e.g., love, fortunate, husband), reflecting positive affect and connection.

Words significantly associated with low well-being (red) and high well-being autonomy (green) and satisfaction with life (blue) are displayed in the embedding space. a Shows words significantly associated with autonomy, and b shows words significantly associated with satisfaction with life. Font size reflects word frequency. The x-axis represents association strength (the dot product along the primary embedding dimension), with higher values indicating stronger associations with higher well-being. The y-axis is used only for visual separation and has no interpretive meaning.

Comparison to state-of-the-art LLMs

Do GPT language‑based assessments of satisfaction with life converge with self-reports?

GPT-3.5

Results showed that GPT-3.5-generated satisfaction with life ratings strongly correlated with self-reported scores (r(283) = 0.71, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.65, 0.77]; Fig. 4). Predictions also moderately converged with self-acceptance (r(283) = 0.61, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.53, 0.68]) and environmental mastery (r(283) = 0.51, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.41, 0.59]), but were weaker for personal growth (r(283) = 0.25, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.13, 0.35]), positive relations (r(283) = 0.21, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.09, 0.32]), and autonomy (r(283) = 0.15, p = 0.014, 95% CI [0.03, 0.26]). The correlation with purpose in life was not significant (r(283) = 0.10, p = 0.083, 95% CI [–0.01, 0.22]).

GPT-4

GPT-4-generated satisfaction with life ratings were strongly correlated with self-reported scores (r(283) = 0.75, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.69, 0.79]; Fig. 4). Predictions also converged moderately with self-acceptance (r(283) = 0.65, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.57, 0.71]) and environmental mastery (r(283) = 0.57, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.47, 0.63]), and more weakly with personal growth (r(283) = 0.24, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.16, 0.37]), positive relations (r(283) = 0.16, p = 0.010, 95% CI [0.04, 0.26]), purpose in life (r(283) = 0.14, p = 0.011, 95% CI [0.04, 0.26]), and autonomy (r(283) = 0.13, p = 0.028, 95% CI [0.01, 0.24]).

How does performance of GPT language-based assessments of autonomy compare to that of satisfaction with life?

GPT-3.5

GPT-3.5-generated autonomy ratings were moderately correlated with self-reported autonomy (r(283) = 0.41, p < .001, 95% CI [0.30, 0.50]), and showed modest convergence with self-acceptance (r(283) = 0.30, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.19, 0.40]), environmental mastery (r(283) = 0.29, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.18, 0.39]), and satisfaction with life (r(283) = 0.29, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.18, 0.39]). Correlations with personal growth (r(283) = 0.09, p = 0.132, 95% CI [–0.03, 0.20]), positive relations (r(283) = 0.07, p = 0.248, 95% CI [–0.05, 0.18]), and purpose in life (r(283) = 0.06, p = 0.287, 95% CI [–0.05, 0.18]) were not significant.

GPT-4

GPT-4-generated autonomy ratings showed stronger correspondence with self-reported autonomy (r(283) = 0.49, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.40, 0.58]). Predictions also moderately converged with environmental mastery (r(283) = 0.34, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.23, 0.44]), satisfaction with life (r(283) = 0.34, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.23, 0.44]), and self-acceptance (r(283) = 0.25, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.14, 0.36]). A weaker correlation emerged with personal growth (r(283) = 0.14, p = 0.018, 95% CI [0.03, 0.25]); correlations with purpose in life (r(283) = 0.11, p = 0.060, 95% CI [–0.00, 0.23]) and positive relations with others (r(283) = 0.02, p = 0.702, 95% CI [–0.09, 0.14]) were not significant.

Comparing correlations

We compared our observed correlations with those reported in prior work as well as across different model types. A Fisher’s r-to-z transformations with a z-test revealed the correlation between our BERT-based language assessment of life satisfaction and self-reported life satisfaction (r = 0.62) was significantly lower than the correlation reported by Kjell et al.14 (r = 0.74) (z = –3.13, p = 0.002, 95% CI [–0.35, –0.08]).

Next, we compared performance across between language models in our Study using Williams’s Test (i.e., testing for a statistically significant difference between dependent correlations sharing one variable)40. For autonomy, correlations with self-reports did not significantly differ between BERT and GPT-4 (r = 0.41 vs. 0.49) (t = –1.53, p = 0.128, 95% CI [–0.23, 0.04]), nor between BERT and GPT-3.5 (r = 0.41 vs. 0.41), (t = 0.01, p = 1.00, 95% CI [–0.14, 0.14]). In contrast, GPT-4 showed significantly stronger correlations than GPT-3.5 for autonomy (r = 0.49 vs. 0.41), t = –2.98, p = 0.003, 95% CI [–0.15, –0.06]). For satisfaction with life, GPT-4 achieved a stronger correlation with self-reported scores than BERT (r = 0.75 vs. 0.62), (t = –5.61, p < 0.001, 95% CI [–0.30, –0.18]), and GPT-3.5 also exceeded BERT (r = 0.71 vs. 0.62), (t = –3.50, p = 0.001, 95% CI [–0.23, –0.09]). GPT-4 additionally outperformed GPT-3.5 (r = 0.75 vs. 0.71), (t = –3.36, p = 0.001, 95% CI [–0.11, –0.07]).

Finally, using Steiger’s Test39, we examined differences between autonomy and satisfaction-with-life correlations within each language model. In all cases, correlations with satisfaction with life were significantly stronger than those with autonomy: BERT (r = 0.62 vs. 0.41), (z = 3.44, p = 0.001, 95% CI [–0.43, –0.12]); GPT-3.5 (r = 0.71 vs. 0.41), (z = 5.36, p < 0.001, 95% CI [–0.55, –0.28]); and GPT-4 (r = 0.75 vs. 0.49), (z = 5.19, p < 0.001, 95% CI [–0.54, –0.27].

General discussion

Language-based assessments and advanced NLP methods have successfully predicted subjective well-being14, but their effectiveness in capturing psychological well-being constructs like autonomy25 remains unclear. Across three studies, we tested whether narrative language-based assessments could reliably predict self-reported autonomy and how this compared to satisfaction with life. Results showed that although language-based models captured broad well-being dimensions, they predicted autonomy less accurately than life satisfaction. Language linked to lower well-being involved coping and evaluative words indicating rumination, whereas high-autonomy reflections combined insight with action-oriented language, and high life satisfaction featured positive social language. Benchmarking our models against state-of-the-art language models showed that newer models significantly improved satisfaction predictions but did not significantly improve autonomy predictions, perhaps reflecting the more diffuse nature of autonomy. Overall, our findings demonstrate both the potential and current boundaries of language-based well-being assessments, underscoring the need to clarify their scope before wider use.

While we replicated prior findings that language-based assessments of satisfaction with life converge with self-reports14, our models showed lower accuracy. Across three studies, we ruled out certain methodological factors, such as modality (text vs. audio), as primary explanations. Differences in sample characteristics may explain the improved accuracy in Study 3 (a diverse U.S. online sample) compared to Study 2 (college students surveyed during end-of-term stress). One untested factor that may account for the significantly smaller effect sizes relative to Kjell et al.14 is our use of narrative responses rather than keyword inputs. Although narrative responses can enable naturalistic, rich, context-dependent language, their greater variability in composition may weaken convergence with structured self-report scales relative to keyword responses, which have been shown to possess higher validity (e.g., correlation to rating scales)14.

We also compared how accurately language-based models assess autonomy versus satisfaction with life. Prior research suggests that language-based analyses can approach the theoretical upper limits of prediction accuracy for subjective well-being6. In Studies 2 and 3, language-based predictions of satisfaction with life significantly correlated more strongly with self-reports than autonomy predictions. Benchmarking against GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 revealed that state-of-the-art LLMs significantly improved satisfaction predictions but only modestly enhanced autonomy predictions compared to our BERT-based models. Together, these results suggest that newer GPT models may provide marginal improvements for some constructs and highlight a fundamental distinction between the constructs when evaluated through language.

When we analyzed words in embedding space, high satisfaction with life responses were anchored in social and affective language, whereas low satisfaction responses were characterized by cognitive processing and function words indicative of active problem solving12. Our findings align with prior research linking satisfaction with life to positive emotions and low distress3,24, detectable in language with small to moderate effects41. In contrast, autonomy-related language exhibited less clear distinctions: both high- and low-autonomy reflections relied on cognitive and function words, though high-autonomy responses uniquely incorporated insight and action-oriented terms. These language features suggest that, in our studies, autonomy is reflected in more individualized and context-dependent language to capture self-directed action and meaning-making. This variability in expression is consistent with Self-Determination Theory, which posits autonomy as a subjective sense of following one’s own goals and values42,43. Indeed, autonomy seems inherently more variable across individuals, making it more challenging to detect reliably through language. Despite NLP advances, our results suggest autonomy and other nuanced well-being dimensions may need more construct-specific modeling. Echoing prior calls7,44, we stress the importance of understanding the boundaries of these methods before replacing traditional self-reports at scale.

In addition to within-construct convergence, we saw that language-based assessments of both satisfaction with life and autonomy converged with other components of subjective and psychological well-being. This aligns with and extends existing research on the interrelation of subjective and psychological well-being components8,20,23, showing that this connection is present even when assessed with language. The ability of these language-based measures to capture multiple facets of well-being is exciting and underscores their potential, with careful development, as ecologically valid tools for assessing the various components that support subjective and psychological well-being.

Limitations

Despite our work’s strengths, including the use of state-of-the-art NLP techniques, several limitations exist. First, this research only focuses on examining the relationship between language-based assessments and self-reported rating scales. It does not compare which of the two is more valid or reliable. Even though self-report scales are validated measures, they should not be viewed as ground truth, but rather approximations about one’s state. In fact, recent research has shown that language-based responses analyzed with computational methods can classify narratives into groups more accurately than analyses of rating scales45,46. Thus, the relative strengths and weaknesses of different approaches are still being evaluated. We encourage additional research that not only examines self-report scales vs. self-report narratives but also integrates these streams of data with reports from others (e.g., friends, clinicians), biological data, or passively-sensed data. Exploring the language-based assessment of other psychological well-being components may broaden the field’s understanding of the boundaries of language-based assessments of well-being. Second, despite applying quality control procedures (including manual review), it remains possible that some participants relied on AI tools when producing their written reflections. This concern is especially relevant for Studies 2–3, which were conducted during a period of widespread and accelerating LLM adoption.

Third, our study focused on models using BERT-based embeddings and state-of-the-art LLMs for language-based well-being predictions. While these models offer valuable context-sensitive insights47, they have limitations. Research has shown that more modern LLMs can outperform older methods like bag-of-words (e.g., LIWC) and pre-trained language models (e.g., RoBERTa), as seen in our study, where GPT outperformed BERT. However, LLMs are costly48, prone to biases from unrepresentative training data49, and operate as black boxes with limited interpretability in closed-source models. Additionally, their outputs can be sensitive to prompt phrasing and few-shot examples, reducing reliability across contexts50,51,52. Researchers should weigh these factors when choosing language model architectures for specific applications in mental health and well-being research (see Mesquiti & Nook53 for a review).

Another limitation is that correlations between language‑based model outputs and self‑report scores may be influenced by the size of the training data used when constructing our models. Prior work suggests that, as the number of observations increases, the correlation between predicted and actual scores tends to improve and may plateau only once samples reach several hundred individuals54. While our samples fall within a range that has been associated with moderate‑to‑high predictive validity, readers might view our reported correlations with an understanding that sample size could have a modest influence.

Lastly, the current sample was limited to respondents from the United States, which limits the generalizability of findings. Culture profoundly shapes how individuals express psychological constructs like emotion, self-concept, and social values, all of which influence language use55,56. As a result, language models trained or validated exclusively on data from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic populations may yield biased or inaccurate predictions when applied to different cultural groups47,55,57. These findings underscore the importance of culturally diverse training data, as well as caution in applying models without appropriate validation.

While our findings offer insights into language-based assessments of psychological well-being, several avenues for future research remain. First, expanding automated psychological assessments to include additional states and traits could enhance the ecological validity of this approach. Future studies should also examine the predictive power of diverse text sources. In our study, participants were explicitly prompted to reflect on their well-being, which likely heightened the relevance and clarity of their language for psychological assessment. However, it remains an open question whether similar levels of accuracy for components of psychological well-being can be achieved using more passive text sources, such as everyday conversations, journal entries, or social media posts, where references to well-being are less direct. Comparing these different types of language could help clarify how context and linguistic styles influence the detectability of psychological constructs. Such work would also speak to the generalizability of language-based well-being assessments across settings and populations. We encourage future work to pursue these directions, particularly given the growing interest in automated, language-based assessments in social science.

Our research highlights the promise of modern NLP tools in predicting self-reported well-being, revealing nuanced links between linguistic patterns and distinct dimensions of psychological functioning. These findings also emphasize the importance of recognizing the boundaries of current NLP techniques. Even with rapid advancements in prompt engineering and model training, LLMs can still produce inaccurate assessments. In our studies, LLMs were notably more effective at detecting satisfaction with life than autonomy, suggesting that these models may be better at recognizing straightforward expressions of well-being than more idiosyncratic, self-reflective dimensions of functioning. In practice, this raises caution about their use as assessment tools in mental health care. If LLMs struggle to capture context-dependent qualities like autonomy, they may fall short in supporting interventions that hinge on the assessment of other idiosyncratic qualities. As automated methodologies, like LLMS, become increasingly central to well-being research, refining these tools is essential for ensuring more accurate and meaningful assessments. This work sets the stage for future innovations in psychological evaluation and intervention, with the potential to better understand well-being at individual, community, and societal levels.

Data availability

Data needed to reproduce our main findings are available at: https://github.com/cnlab/LP2-wellbeing-prediction/tree/main/data.

Code availability

The code needed to reproduce our main findings are available at: https://github.com/cnlab/LP2-wellbeing-prediction or https://osf.io/qac8j/files/mbgjy?view_only=fa6a39b16a1c43a4afa2fb81d5cccb28.

References

Diener, E. New findings and future directions for subjective well-being research. Am. Psychol. 67, 590–597 (2012).

Huppert, F. A. & So, T. T. C. Flourishing across Europe: application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 110, 837–861 (2013).

Oishi, S., Diener, E. & Lucas, R. E. The optimum level of well-being: can people be too happy?. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2, 346–360 (2007).

Allin, P. & Hand, D. J. New statistics for old?—measuring the wellbeing of the UK. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 180, 3–43 (2017).

Jackson, J. C. et al. From text to thought: how analyzing language can advance psychological science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 17, 805–826 (2022).

Kjell, O., Kjell, K. & Schwartz, H. A. Beyond rating scales: with targeted evaluation, large language models are poised for psychological assessment. Psychiatry Res 333, 115667 (2024).

Nook, E. C. The promise of affective language for identifying and intervening on psychopathology. Affect. Sci. 4, 517–521 (2023).

Ruggeri, K., Garcia-Garzon, E., Maguire, Á, Matz, S. & Huppert, F. A. Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: a multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 18, 192 (2020).

Boyd, R. L. & Markowitz, D. M. Verbal behavior and the future of social science. Am. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001319 (2024).

Eichstaedt, J. C. et al. Closed-and open-vocabulary approaches to text analysis: a review, quantitative comparison, and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 26, 398 (2021).

Kern, M. L. et al. Gaining insights from social media language: methodologies and challenges. Psychol. Methods 21, 507–525 (2016).

Tausczik, Y. R. & Pennebaker, J. W. The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 29, 24–54 (2010).

Seraj, S., Blackburn, K. G. & Pennebaker, J. W. Language left behind on social media exposes the emotional and cognitive costs of a romantic breakup. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2017154118 (2021).

Kjell, O. N. E., Sikström, S., Kjell, K. & Schwartz, H. A. Natural language analyzed with AI-based transformers predict traditional subjective well-being measures approaching the theoretical upper limits in accuracy. Sci. Rep. 12, 3918 (2022).

Hur, J. K., Heffner, J., Feng, G. W., Joormann, J. & Rutledge, R. B. Language sentiment predicts changes in depressive symptoms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2321321121 (2024).

Nook, E. C., Hull, T. D., Nock, M. K. & Somerville, L. H. Linguistic measures of psychological distance track symptom levels and treatment outcomes in a large set of psychotherapy transcripts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2114737119 (2022).

Rai, S. et al. Key language markers of depression on social media depend on race. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2319837121 (2024).

Stade, E. C., Ungar, L., Eichstaedt, J. C., Sherman, G. & Ruscio, A. M. Depression and anxiety have distinct and overlapping language patterns: results from a clinical interview. J. Psychopathol. Clin. Sci. 132, 972–983 (2023).

Mesquiti, S. et al. Analysis of social media language reveals the psychological interaction of three successive upheavals. Sci. Rep. 15, 5740 (2025).

Gallagher, M. W., Lopez, S. J. & Preacher, K. J. The hierarchical structure of well-being. J. Personal. 77, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00573.x (2009).

Keyes, C. L. M. Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 73, 539–548 (2005).

Keyes, C. L. M. Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: a complementary strategy for improving national mental health. Am. Psychol. 62, 95–108 (2007).

Woerkom, M. van. et al. Networks of happiness: applying a network approach to well-being in the general population. J. Happiness Stud. 23, 3215–3231 (2022).

Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 95, 542–575 (1984).

Ryff, C. D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 57, 1069–1081 (1989).

Hoemann, K. et al. The construction of emotional meaning in language. Commun. Psychol. 3, 99 (2025).

Pavot, W. & Diener, E. The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. J. Posit. Psychol. 3, 137–152 (2008).

Ryff, C. D. & Keyes, C. L. M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 69, 719–727 (1995).

Kjell, O., Giorgi, S. & Schwartz, H. A. The text-package: an R-package for analyzing and visualizing human language using natural language processing and transformers. Psychol. Methods https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000542 (2023).

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1810.04805 (2019).

Ganesan, A. V., Matero, M., Ravula, A. R., Vu, H. & Schwartz, H. A. Empirical evaluation of pre-trained transformers for human-level NLP: the role of sample size and dimensionality. Proc. Conf. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. North Am. Chapter Meet. 2021, 4515–4532 (2021).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Phonic. Phonic-Voice and Video Surveys https://www.phonic.ai/ (2023).

Porter, M. Snowball: a language for stemming algorithms. http://snowball.tartarus.org/texts/introduction (2001).

Fisher, R. A. Statistical Methods for Research Workers 4th edn, Vol. xi, 307 (Oliver & Boyd, Oxford, England, 1932).

Pennebaker, J. W., Boyd, R. L., Booth, R. J., Ashokkumar, A. & Francis, M. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count: LIWC-22. Pennebaker Conglomerates, Inc. https://www.liwc.app/ (2022).

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G. & Aiken, L. S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203774441 (Routledge, 2013).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587 (Routledge, 1988).

Steiger, J. Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychol. Bull. 87, 245–251 (1980).

Williams, E. J. The analysis of association among many variates. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 29, 199–228 (1967).

Munin, S., Ong, D. C., Okland, S., Freedman, G. & Beer, J. S. Language measures correlate with other measures used to study emotion. Commun. Psychol. 3, 1–9 (2025).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268 (2000).

Ryan, R. et al. We know this much is (meta-analytically) true: a meta-review of meta-analytic findings evaluating self-determination theory. Psychol. Bull. 148, 813 (2023).

Malgaroli, M., Hull, T. D., Zech, J. M. & Althoff, T. Natural language processing for mental health interventions: a systematic review and research framework. Transl. Psychiatry 13, 1–17 (2023).

Sikström, S., Nicolai, M., Ahrendt, J., Nevanlinna, S. & Stille, L. Language or rating scales based classifications of emotions: computational analysis of language and alexithymia. Npj Ment. Health Res. 3, 37 (2024).

Sikström, S., Valavičiūtė, I., Kuusela, I. & Evors, N. Question-based computational language approach outperforms rating scales in quantifying emotional states. Commun. Psychol. 2, 1–11 (2024).

Mihalcea, R. et al. How developments in natural language processing help us in understanding human behaviour. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 1877–1889 (2024).

Narayanan, D. et al. Efficient large-scale language model training on GPU clusters using megatron-LM. In Proc. International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1145/3458817.3476209 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2021).

Demszky, D. et al. Using large language models in psychology. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-023-00241-5 (2023).

Anagnostidis, S. & Bulian, J. How susceptible are LLMs to influence in prompts? Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2408.11865 (2024).

Binz, M. et al. How should the advancement of large language models affect the practice of science?. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 122, e2401227121 (2025).

Chen, L., Zaharia, M. & Zou, J. How is ChatGPT’s behavior changing over time? Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2307.09009 (2023).

Mesquiti, S. & Nook, E. C. Artificial intelligence in mental health treatment and research. Preprint at https://osf.io/jvf2z_v1 (2025).

Kjell, O. N. E., Kjell, K., Garcia, D. & Sikström, S. Semantic measures: using natural language processing to measure, differentiate, and describe psychological constructs. Psychol. Methods 24, 92–115 (2019).

Charlesworth, T. E. S., Morehouse, K., Rouduri, V. & Cunningham, W. Echoes of culture: relationships of implicit and explicit attitudes with contemporary English, historical English, and 53 non-English languages. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 15, 812–823 (2024).

Michel, J.-B. et al. Quantitative analysis of culture using millions of digitized books. Science 331, 176–182 (2011).

Charlesworth, T. E. S., Yang, V., Mann, T. C., Kurdi, B. & Banaji, M. R. Gender stereotypes in natural language: word embeddings show robust consistency across child and adult language corpora of more than 65 million words. Psychol. Sci. 32, 218–240 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Lentic Fund, which is an unrestricted gift from Lotic.ai to E.B.F. Lotic.ai had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. E.C.N. is supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (31386) and a Princeton Precision Health seed grant. We are indebted to the following people for support, advice, and/or feedback on earlier drafts of the paper: Bernice Cheung and Drs. Anne Park, Suzanne Button, Tania Lombrozo, and James Pennebaker.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M., D.C., E.C.N., E.B.F., and S.B. designed the studies. S.M. and D.C. collected, processed, and extracted the data. S.M. analyzed the data under the supervision of S.B., D.C., and E.B.F. S.M., D.C., E.C.N., E.B.F., and S.B. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

E.B.F. serves on the scientific advisory board for Kumanu and has done consulting for Panasonic Well. S.M., D.C., E.C.N., and S.B. declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Psychology thanks Sverker Sikström and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jixing Li and Jennifer Bellingtier. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mesquiti, S., Cosme, D., Nook, E.C. et al. Language-based assessments can predict psychological and subjective well-being. Commun Psychol 4, 33 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-026-00400-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-026-00400-3