Abstract

Background

In Ireland, cancer is a leading cause of mortality. Optimising primary care cancer research is crucial for better patient outcomes and healthcare policies. This study identifies Irish health data resources relevant to primary care cancer research, addressing a gap in understanding data availability and utility to enhance cancer care.

Methods

We conducted a comprehensive review of Irish health data resources across multiple platforms, including a broad data search, expert consultations, literature review, and data synthesis. An expert roundtable refined our findings.

Results

Our review identified 39 data resources, including national registries, biobanks, and health system audits. We noted varying levels of data accessibility and comprehensiveness, with several datasets offering significant potential. Emergent themes focused on data quality and practical utility to address specific primary care cancer research questions.

Conclusion

This review provides a foundational resource for primary care cancer researchers in Ireland, highlighting available data, potential gaps, and challenges. The resulting data catalogue will guide future research, supporting evidence-based strategies and advancing health informatics and cancer research.

Highlights

-

This comprehensive review identifies and evaluates a diverse range of Irish health data resources, establishing a foundational catalogue for advancing primary care cancer research in Ireland.

-

The study highlights significant gaps in data accessibility and utility, underlining the need for enhanced data integration and linkage to improve research outcomes and healthcare strategies.

-

Our findings provide a roadmap for policymakers and researchers, recommending the optimisation of existing datasets to support evidence-based cancer care strategies and inform future healthcare improvements in Ireland.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is a significant health challenge globally, ranking as the second leading cause of death, years of life lost, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) according to the 2019 Global Burden of Disease study [1]. In Ireland, the burden of cancer is particularly high, with the European Commission identifying it as having the highest cancer incidence in the European Union in 2020. The National Cancer Registry Ireland (NCRI) estimated an annual average of 44,000, invasive cancer cases diagnosed between 2020 and 2022 [2,3,4]. This high incidence underlines the urgent need for effective cancer prevention and management strategies.

General Practitioners (GPs) are integral to the cancer care continuum, providing services that span prevention, early detection, treatment, survivorship, and end-of-life care. As the first point of contact for many patients, GPs influence patient outcomes through timely diagnosis and coordinated care [5]. The analysis of routinely collected healthcare data in primary care can identify risk factors for various cancer types, leading to more effective prevention strategies and reduced diagnostic intervals [6]. However, a significant gap exists in the integration and use of primary care data in cancer research. This study aims to help address this gap by cataloguing and evaluating Irish health data resources relevant to primary care cancer research.

Health data in cancer research

Healthcare data is fundamental for evaluating and improving cancer care. Reliable and detailed data allow researchers to understand disease patterns, identify risk factors, and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions [7].

In Ireland, cancer research utilizes various health data sources, including registry data from the NCRI, biobanks, health surveys, audits, and screening datasets from HSE national programmes. While registry data offer patient-level insights into cancer trends, the lack of primary care data limits a comprehensive view of the patient journey [8]. Biobanks support personalized medicine [9, 10], and non-individual level data from audits like National Audit of Hospital Mortality and the Irish Paediatric Critical Care Audit help assess healthcare quality [11, 12]. Additionally, socio-economic and environmental factors influencing cancer are explored through datasets from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and large social studies such as The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) and the Survey of Lifestyle, Attitudes and Nutrition (SLÁN) [13,14,15,16].

Despite the wealth of data, challenges remain in collecting cancer-relevant healthcare data in Ireland, as 85% of hospital-based healthcare records are paper-based. This underlines the need for improved data infrastructure [17, 18].

International context and best practices

Internationally, there are multiple examples of how large analytical datasets enhance cancer research. In the UK, resources like the UK BioBank, Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), and OpenSafely contain linked healthcare records for millions of individuals, facilitating extensive research into cancer patterns and outcomes [19]. The USA’s Veterans Affairs Corporate Data Warehouse has been used to study cancer screening patterns and treatment efficacy, providing valuable insights into effective cancer care strategies [20,21,22,23]. The European Cancer Observatory combines national registry information from across Europe on cancer incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence, offering a comprehensive resource for comparative research [24].

Large developing biobank initiatives, such as the UK’s Our Future Health project, aim to advance early diagnostic technology and preventive interventions by inviting citizens to provide biological samples and health information [25]. In Australia, the MedicineInsight database, a large-scale primary care database of longitudinal de-identified electronic health records (EHRs), has proven useful in tracking diagnosis rates for conditions such as melanoma skin cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic [26, 27]. In the Netherlands, the Julius General Practitioners’ Network (JGPN) database supports a wide range of research, including aetiological, diagnostic, and intervention studies [28, 29].

In Ireland, there is a need to define the existing cancer-relevant datasets so work can begin to optimise the use of this data in primary care cancer research.

Aims and objectives

This study aims to systematically catalogue and evaluate health data resources relevant to primary care cancer research in Ireland. The specific objectives are to:

-

1.

Identify and characterise cancer-relevant health data sources in Ireland, focusing on primary care.

-

2.

Appraise the accessibility of these data sources and identify gaps in data availability.

-

3.

Recommend strategies for optimal utilisation of these data sources in future primary care cancer research.

Methods

This study employs a systematic approach to map Irish health data resources relevant to primary care cancer research. Our methods include an literature review and expert roundtable discussion.

Literature review

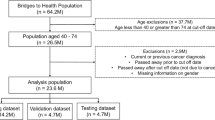

We identified relevant literature focusing on English language articles from journals and book chapters, sourced primarily from the PubMed database. The selection was based on a structured template tailored to our study, with no constraints on the publication date of the articles. This process involved all team members, who contributed to refining the literature list for manuscript development. The formal literature review was supplemented by a grey literature review (Fig. 1).

Eligibility criteria

Research was included if it pertained to databases created in the Republic of Ireland that are relevant to primary care cancer research and broadly applicable to multiple research questions.

Databases not available in English were excluded. Datasets including data from Northern Ireland were omitted due to contextual and legislative differences. A list of identified Northern Irish datasets is included in Supplementary Appendix item 4.

Our search strategy, designed in collaboration with a medical librarian, is detailed in Supplementary Appendix Item 1.

Data extraction

We extracted information using a predetermined template (Supplementary Appendix Item 3) documenting characteristics like dataset types, collection methods, geographical coverage, accessibility and size. The extraction process was conducted through shared tables in Google Sheets.

Sampling and screening

Initial screening of references was performed using EndNote software, with a systematic dual Cochrane rapid review screening process applied [30] (Supplementary Appendix Item 1). Our strategy for full-text article retrieval and the independent review of these articles helped maintain a level of consistency in our selection process. All discrepancies in inclusion decisions were resolved through consensus agreement among the reviewers. Expert roundtable discussion and feedback.

After completing a preliminary analysis of potential data sources through our search strategy and literature review, we organised a roundtable discussion with key stakeholders and experts. Experts were initially contacted based on their involvement and expertise in health data cancer research. We utilising a snowball sampling strategy; these experts recommended additional informants, thereby expanding the resource pool for our study.

This group included two researchers & policymakers in Irish cancer research, one clinician and a patient and public involvement (PPI) representative. Emphasis was placed on the importance of data protection and patient confidentiality, ensuring ethical use of the data sources.

The roundtable was conducted via videoconference. Key points of discussion included the relevance of identified data sources for primary care cancer research, identifying challenges or limitations in their usage, and considering potential additions to our list.

In addition to the roundtable, the identified databases were circulated via email to a broader group of experts in primary care cancer research. Of the ten experts contacted, five responded. These experts were invited to provide feedback on the completeness and relevance of the listed data sources. Responses were collected, consolidated, and integrated into the final dataset catalogue.

Data synthesis

The identified datasets from the literature review and expert consultations were compiled into a catalogue. This process included categorizing datasets based on data type thematic relevance, and accessibility. The synthesis also involved cross-referencing findings from the expert roundtable to validate the completeness and relevance of the identified data sources, ensuring a comprehensive representation of Irish health data relevant to primary care cancer research.

Datasets were assigned codes. The codes denote the type of data within each dataset. The codes are (i)Indiv/Cancer; (ii) Indiv/Health; (ii) Indiv/Social; (iv) Indiv/Cancer/Bio; (v) Nonin/Audit; (vi)Nonin/Cencus; (vii) Nonin/Environmental; (iix) Indiv/Bio.

The datasets have been initially divided into either individual-level or non-individual-level patient data. Individual level datasets have been further subdivided into data that is cancer-specific, biobank data, health but not solely cancer-related data and social data. Social data relates to data that primarily related to demographic or social science data but which may also contain relevant health data. Non-individual is aggregate data that has been further subdivided into data from audits or health reporting, national census data and environmental data (which has no patient data present at all).

Furthermore, all data present has been assigned themes describing the nature of the data content in a more general way. (i) Disease registry data; (ii) Screening programme data; (iii) Small-scale/institutional data relates to smaller-scale data that is hosted at either one or two institutions with defined geographical or population boundaries relating to the jurisdiction of the institution, rather than national or multi-institutional data; (iv) Mixed data are datasets that contains both individual cancer-specific patient data and biobank data; (v) Historic data are datasets that are no longer active and have been integrated into other, live, datasets; (vi) Hospital data is data derived from hospital administrative records on hospital discharges; (vii) Cancer-specific biological data; are biobank datasets specific to cancer; (iix) Biobank denotes biological datasets that are not specific to cancer; (ix) Cencus data from the national census; (x) Non-clinical social science data; (xi) Environmental data; (xii) Health system audits and reporting; (xiii) Mortality data are datasets registering national mortality; (xiv) Miscellaneous datasets do not fit easily into a given category.

Results

Literature review and data source identification

A systematic search identified 6789 unique citations. Following screening, 274 full-text articles were reviewed, of which 32 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The grey literature review supplemented this with five relevant datasets. The expert roundtable discussions facilitated the identification of two additional datasets not captured in the literature review. This process resulted in a total of thirty-nine datasets.

In addition to the thirty-nine datasets described, three previously existing dataset repositories emerged as highly relevant to the primary care setting. A dataset is a single collection of related data, while a dataset repository is a collection that stores and organizes multiple datasets. The three identified repositories are: 1) Health Atlas Ireland contains over 1.7 million records covering areas such as demography, hospital activity, and mortality. Although this breadth of data is comprehensive, its restricted access limits usability for external researchers. 2) The Joint Irish Nutrigenomics Organisation (JINGO) datasets offer lifestyle and nutritional information on 7000 participants through the TUDA study, NANS, and MECHE, supporting research into the role of lifestyle factors and genomics in cancer outcomes. 3) The Irish Social Science Data Archive (ISSDA) hosts various datasets, including the All Ireland Traveller Health Survey (AITHS) and The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA), which contribute demographic and social data applicable to primary care research (Table 1).

Data source themes and classification

The datasets were grouped based on their data type (individual-level vs non-individual-level) and thematic relevance (cancer-specific, biobank, health-related, social) (Fig. 2). Individual-level datasets are particularly notable, as they contain detailed clinical data at the patient level. The National Cancer Registry Ireland (NCRI), with over 600,000 records, is one of the most comprehensive sources, documenting cancer incidence, prevalence, and survival since 1991. Other individual-level datasets include national screening programmes such as BowelScreen, CervicalCheck, and BreastCheck, which provide large-scale data on cancer screening and early detection.

33 of the 39 datasets identified were non-individual datasets. Non-individual-level datasets, such as the National Audit of Hospital Mortality (NAHM) and the Irish Paediatric Critical Care Audit (IPCCA), provide system-wide insights into healthcare delivery. These datasets focus on healthcare quality and outcomes, contributing to a broader understanding of the performance of the healthcare system in cancer care.

Table 2 provides a full summary of the identified datasets, detailing their data type, thematic focus, record numbers, controlling organisations, temporal coverage, and accessibility status. The median size of all datasets listed in the table is 9832 records. In the table, in respect to the “Number of records” column, this identifies the existing number of records as per the most recent available information at the time the research was conducted. N/A denotes information that was not openly accessible during the research process. Not all dataset characteristics originally included in the extraction tool feature in the table as for some characteristics, the available data was insufficient to support a meaningful analysis or accurate reporting.

Dataset accessibility

Of the thirty-nine datasets catalogued, six are publicly accessible. These datasets are valuable resources for researchers, as they offer open access to national and environmental data. In order to access the other datasets, access must be specifically granted to approved researchers only.

Cancer type-specific data sources

The categorisation of datasets by cancer type reveals a range of data availability for specific cancers (Table 3). Breast cancer is particularly well-represented across various datasets, including the BreastCheck national screening programme and multiple biobanks, such as the Breast Cancer Ireland Biobank and BREAST PREDICT. These datasets cover various aspects of breast cancer care, from early detection to treatment outcomes. Similarly, IPCOR and BowelScreen provide data on prostate and bowel cancers, respectively.

However, data availability for other cancers, such as pancreatic and neurological cancers, is more limited. Relevant to these cancer types are The National Pancreas Transplant Programme and the Paediatric Neuroblastoma Biobank.

Dataset utility across the cancer care continuum

The datasets have varying utility across different stages of the cancer care continuum. Individual-level cancer data provides the most direct applicability to primary care research, supporting analyses of patient pathways from screening and diagnosis to treatment and survivorship. Thematic mapping of datasets (Fig. 3) shows how they align with different stages of the cancer continuum.

Discussion

This study catalogued thirty-nine Irish health datasets relevant to primary care cancer research, providing a resource for researchers to understand the scope, accessibility, and thematic focus of available data.

Of note, only one dataset was identified that exclusively utilises primary care data. This was the PCRS (Primary Care Reimbursement Service), a non-individual-level dataset that tracks the financial reimbursements made to healthcare primary care healthcare providers. This highlights a significant gap in the health data landscape which limits the potential of future cancer research in the primary care space. Without primary care-specific datasets, it becomes challenging to evaluate diagnostic pathways, referral patterns, and the role of general practitioners in early cancer detection. This gap significantly limits the ability to understand how primary care contributes to timely cancer diagnosis and management.

Key findings highlight the availability of large-scale cancer registries such as the National Cancer Registry Ireland (NCRI), which provides comprehensive data on cancer incidence, prevalence, and survival. Screening datasets like CervicalCheck and BowelScreen contribute valuable insights into population-level screening uptake and diagnostic pathways. The thematic analysis shows a strong presence of data sources for breast, prostate, and bowel cancer research, while less common cancers, such as pancreatic or neurological cancers, are less comprehensively represented.

Context of existing research

The comprehensive mapping of Irish health datasets reveals a potential for advancing primary care cancer research, in line with international trends. Dataset linkage enables the combination of patient data from diverse sources, such as primary care records, hospital data, and socioeconomic information, providing a holistic view of patient care pathways and facilitating better-informed research and policy [31,32,33]. Dataset linkage refers to ‘the bringing together from two or more different sources, data that relate to the same individual, family, place or event’ [34]. Examples of this exist in Canada, where linked health and socioeconomic datasets have been utilised to develop a range of microsimulation models with a view to analysing policy and health management system resilience in the face of unexpected events [35].

In Australia, the utilisation of data linkage platforms has informed a wide range of cancer research and policy development. Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre Data Connect is a single platform for facilitating access to a range of Victorian health data sources [36]. Data connect consists of linked hospital and primary care data. Uses for Data Connect to date include the analysis of diagnostic intervals for lung and colorectal cancers [10, 37] and improving primary care diagnostic tools in the early detection of cancer [36].

Large datasets such as the CPRD and Data Connecthave paved the way for evidence-based practices and targeted interventions through facilitating research into risk profiling, new models of care delivery and innovative interventions. Research into the ethnic differences in hypertension management utilising these datasets show the potential for their integration to provide more tailored patient-centred care [38,39,40]. Diagnostic tools such as electronic clinical decision support tools (eCDSTs), developed and validated through these large datasets, have shown a potential to impact improvements in decision making related to cancer diagnosis and reduced time to diagnosis [41, 42].

The Irish healthcare context brings unique considerations for the application of these findings. Primary care is often the first point of contact for cancer patients, making it critical to have access to real-time, comprehensive data. Data from screening programmes such as CervicalCheck and BowelScreen are highly relevant for understanding population-level screening uptake and outcomes. However, the limited open access to cancer-specific datasets, along with fragmented data governance policies, creates barriers to research and limits the ability to address research gaps effectively. There is a clear opportunity to enhance data-sharing frameworks, which would align Irish practices with existing international data-sharing frameworks and maximise the utility of existing datasets.

Limitations

This study faces several methodological limitations. One significant limitation relates to dataset accessability. While we aimed to include a wide range of data sources, the accessibility and availability of these datasets varied, potentially leading to an incomplete representation of all relevant health data resources. There is the potential for selection bias in the identification of data sources, as our search strategies and inclusion criteria may have inadvertently favoured certain types of datasets. Additionally, while we sought to include a wide range of experts and stakeholders in our consultations, the scope of our expert input may have been limited by logistical and time constraints, potentially impacting the breadth of insights gathered.

Implications for policy, research, and practice

The findings have implications for policy, research, and clinical practice in Ireland.From a policy perspective, the development of an open-access data catalogue as a resource for primary care cancer research aligns with broader goals to improve health data governance and accessibility. Policymakers could leverage this catalogue to prioritise efforts in data integration, establish clearer access protocols, and enhance the utility of data sources for informing national cancer care strategies.

For researchers, the catalogue serves as a centralised reference to identify existing datasets, reducing time spent on data search and allowing greater focus on analysis and application. It also highlights the importance of multidisciplinary collaborations, as linking diverse data types—such as clinical records, biobanks, and socioeconomic data—can produce comprehensive research insights. The study also suggests areas where data collection could be improved.

In clinical practice, the insights from this study could support the development of targeted interventions for specific patient groups based on their primary care pathways. The potential development of clinical decision support tools (eCDSTs) based on integrated data, as evidenced in UK practices, could significantly improve diagnostic accuracy and timely referral for suspected cancers [40].

Recommendations for future research, practice, and policy

These recommendations are directly based on the findings from the expert consultation and data synthesis, outlined in the results section, addressing the gaps in cancer-relevant health datasets identified during the dataset mapping process and outlined. Based on these results, future research should focus on developing a user-friendly online platform to centralise access to these datasets, incorporating detailed metadata and access protocols to facilitate researchers’ work. There is a need to evaluate data quality indicators to understand the reliability and completeness of datasets for primary care cancer research applications. Monitoring the data using standardised metrics could enhance the reliability of the repository researches. Efforts to streamline ethical approvals, data-sharing agreements, and compliance with GDPR will be crucial to enhance data accessibility while protecting patient privacy. Additionally, exploring data integration possibilities across primary and secondary care settings is essential to ensure that linked datasets can provide a full view of the patient care pathway. Expanding data collection efforts to improve the representation of less prevalent cancers, as well as incorporating social determinants of health, would enrich the catalogue’s relevance for primary care cancer research.

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive overview of Irish health data resources, with a focus on their application in primary care cancer research. By characterising datasets according to their size, theme, coverage, and access conditions, it lays the groundwork for improved data integration and accessibility in Ireland. Implementing the recommendations put forth can guide future research directions, inform policy decisions, and support enhanced cancer care practices in primary care settings.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are derived from publicly available resources identified in the manuscript. The PRiCAN (Primary Care Cancer Research Network) data catalogue, will be accessible via our searchable platform at prican.eu. This platform will offer a comprehensive catalogue of Irish health data resources relevant to primary care cancer research. Each dataset listed in the catalogue will be accompanied by detailed metadata, including access conditions, dataset size, collection period, and geographic coverage.Additionally, supplementary materials, methodologies, and related data files that were used to construct this catalogue will be deposited in Zenodo. These materials can be accessed at Zenodo under the DOI: [10.5281/zenodo.12658132]. This ensures that all resources are preserved in a citable, shareable, and discoverable manner.

References

Global Burden of Disease Cancer C. Cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life years for 29 cancer groups from 2010 to 2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8:420–44.

NCRI. Cancer in Ireland 1994-2022 with estimates for 2020-2022: Annual report of the National Cancer Registry. 2024. Ireland: National Cancer Registry Ireland; 2024.

Joint Research Centre - EU Science - Ireland is the country with the highest cancer incidence in the EU [WWW Document]. 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/eusciencehubnews/items/684847/en. Accessed 12.9.23

National Cancer Registry Ireland. Cancer in Ireland 1994-2018 with estimates for 2018-2020: Annual report of the National Cancer Registry. Ireland: National Cancer Registry Ireland; 2020.

Rubin G, Berendsen A, Crawford SM, Dommett R, Earle C, Emery J, et al. The expanding role of primary care in cancer control. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1231–72.

Canaway R, Boyle DI, Manski-Nankervis JE, Bell J, Hocking JS, Clarke K, et al. Gathering data for decisions: best practice use of primary care electronic records for research. Med J Aust. 2019;210:S12–6.

Liu F, Panagiotakos D. Real-world data: a brief review of the methods, applications, challenges and opportunities. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022;22:287.

Dulaney C, Wallace AS, Everett AS, Dover L, McDonald A, Kropp L. Defining Health Across the Cancer Continuum. Cureus. 2017;9:e1029.

Charmsaz S, Doherty B, Cocchiglia S, Varešlija D, Marino A, Cosgrove N, et al. ADAM22/LGI1 complex as a new actionable target for breast cancer brain metastasis. BMC Med. 2020;18:349.

David W, Usha M, Alina Zalounina F, Henry J, Andriana B, et al. Diagnostic routes and time intervals for patients with colorectal cancer in 10 international jurisdictions; findings from a cross-sectional study from the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership (ICBP). BMJ Open. 2018;8:e023870.

Gunne E, McGarvey C, Hamilton K, Treacy E, Lambert DM, Lynch SA. A retrospective review of the contribution of rare diseases to paediatric mortality in Ireland. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15:311.

Foley J, Cronin M, Brent L, Lawrence T, Simms C, Gildea K, et al. Cycling related major trauma in Ireland. Injury. 2020;51:1158–63.

Dempsey S, Lyons S, Nolan A. High Radon Areas and lung cancer prevalence: evidence from Ireland. J Environ Radioact. 2018;182:12–9.

O’Sullivan K, O’Donovan A. Factors associated with breast cancer mammography screening and breast self-examination in Irish women: results from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Acta Oncologica. 2022;61:1301–8.

Connolly S, Whyte R. Uptake of cancer screening services among middle and older ages in Ireland: the role of healthcare eligibility. Public Health. 2019;173:42–7.

Burns R, Walsh B, Sharp L, O’Neill C. Prostate cancer screening practices in the Republic of Ireland: the determinants of uptake. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2012;17:206–11.

Hickey D, O’Connor R, McCormack P, Kearney P, Rosti R, Brennan R. The data quality index: improving data quality in Irish healthcare records. In: 24th International Conference Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS ‘21). Orcid; SciTEPress: 2021.

Thompson S. Delay in rolling out electronic health records an ‘enormous missed opportunity’. The Irish Times; 2022.

O’Dowd EL, Ten Haaf K, Kaur J, Duffy SW, Hamilton W, Hubbard RB, et al. Selection of eligible participants for screening for lung cancer using primary care data. Thorax. 2022;77:882–90.

Imperiale TF. CRC screening with sigmoidoscopy extends life by 110 d; other cancer screening tests do not extend life. Ann Intern Med. 2024;177:Jc9.

Choi E, Ding VY, Luo SJ, Ten Haaf K, Wu JT, Aredo JV, et al. Risk model-based lung cancer screening and racial and ethnic disparities in the US. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9:1640–8.

Saini SD, Lewis CL, Kerr EA, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Hawley ST, Forman JH, et al. Personalized multilevel intervention for improving appropriate use of colorectal cancer screening in older adults: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183:1334–42.

Mahashabde R, Bhatti SA, Martin BC, Painter JT, Rodriguez A, Ying J, et al. Real-world survival of first-line immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment versus chemotherapy in older patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and synchronous brain metastases. JCO Oncol Pr. 2023;19:1009–19.

Steliarova-Foucher E, O’Callaghan M, Ferlay J, Masuyer E, Rosso S, Forman D, et al. The European cancer observatory: a new data resource. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1131–43.

OFHOFHRP. Our future health research portal. 2025. https://research.ourfuturehealth.org.uk/.

Busingye D, Gianacas C, Pollack A, Chidwick K, Merrifield A, Norman S, et al. Data Resource Profile: MedicineInsight, an Australian national primary health care database. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48:1741-h.

Roseleur J, Gonzalez-Chica DA, Emery J, Stocks NP. Skin checks and skin cancer diagnosis in Australian general practice before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2011-2020. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:853–5.

Sollie A, Roskam J, Sijmons RH, Numans ME, Helsper CW. Do GPs know their patients with cancer? Assessing the quality of cancer registration in Dutch primary care: a cross-sectional validation study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012669.

Smeets HM, Kortekaas MF, Rutten FH, Bots ML, van der Kraan W, Daggelders G, et al. Routine primary care data for scientific research, quality of care programs and educational purposes: the Julius General Practitioners’ Network (JGPN). BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:735.

Garritty C, Gartlehner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B, King VJ, Hamel C, Kamel C, et al. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;130:13–22.

Milne BJ, Atkinson J, Blakely T, Day H, Douwes J, Gibb S, et al. Data resource profile: the New Zealand integrated data infrastructure (IDI). Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48:677-e.

Aanestad M, Grisot M, Hanseth O, Vassilakopoulou P. Information infrastructures within European health care: Working with the installed base. Cham; Springer: 2017.

Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K, Forbes H, Mathur R, Van Staa T, et al. Data resource profile: clinical practice research datalink (CPRD). Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:827–36.

Emery J, Boyle D. Data linkage. Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46:615–9.

Michael W. Conference Handbook. International Health Data Linkage Conference. 2014. https://www.popdata.bc.ca/sites/default/files/documents/events/popdata/IHDLN_2014_Conference_Handbook.pdf.

Lee A, McCarthy D, Bergin RJ, Drosdowsky A, Martinez Gutierrez J, Kearney C, et al. Data resource profile: victorian comprehensive cancer centre data connect. Int J Epidemiol. 2023;52:e292–300.

Usha M, Peter V, Alina Zalounina F, Henry J, Samantha H, Irene R, et al. Time intervals and routes to diagnosis for lung cancer in 10 jurisdictions: cross-sectional study findings from the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership (ICBP). BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025895.

Eastwood SV, Hughes AD, Tomlinson L, Mathur R, Smeeth L, Bhaskaran K, et al. Ethnic differences in hypertension management, medication use and blood pressure control in UK primary care, 2006-2019: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2023;25:100557.

Fahmi A, Wong D, Walker L, Buchan I, Pirmohamed M, Sharma A, et al. Combinations of medicines in patients with polypharmacy aged 65-100 in primary care: large variability in risks of adverse drug related and emergency hospital admissions. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0281466.

Padmanabhan S, Carty L, Cameron E, Ghosh RE, Williams R, Strongman H. Approach to record linkage of primary care data from Clinical Practice Research Datalink to other health-related patient data: overview and implications. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34:91–9.

Koshiaris C, Van den Bruel A, Nicholson BD, Lay-Flurrie S, Hobbs FDR, Oke JL. Clinical prediction tools to identify patients at highest risk of myeloma in primary care: a retrospective open cohort study. Br J Gen Pract. 2021;71:e347.

Chima S, Reece JC, Milley K, Milton S, McIntosh JG, Emery JD. Decision support tools to improve cancer diagnostic decision making in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69:e809.

Acknowledgements

The study team would like to acknowledge and express thanks for the support and participation of the group convened for the expert roundtable discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Oisín Brady Bates: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Article Screening, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Project AdministrationAlexander Carroll: Writing – Review & EditingCaoimhe Hughes: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Article Screening, Writing – Review & EditingCollette Murtagh: Writing – Review & EditingBenjamin Jacob: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Article Screening, Writing – Review & EditingKathleen Bennett: Writing – Review & EditingPatrick Redmond: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and agree to its submission and publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brady Bates, O., Carroll, A., Hughes, C. et al. Cataloguing and evaluating Irish health data resources for primary care cancer research. BJC Rep 3, 59 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44276-025-00170-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44276-025-00170-1