Abstract

Stimulus payment programs have been instrumental in supporting economic activity during the COVID-19 pandemic, yet their public health implications remain underexplored. This study examines a unique policy in Seoul, South Korea, which restricted stimulus spending to recipients’ residential cities, to assess its potential in mitigating virus transmission. Using credit card transactions, mobility records and COVID-19 case data, we apply a triple difference-in-differences approach to analyze how the policy reshaped spatial consumption patterns. Results indicate that while the stimulus program boosted overall spending, it also significantly redistributed spending geographically. The restriction led to reduced consumption outside Seoul and a greater concentration of local spending, effectively limiting mobility. Spillover analysis shows localized consumption had a lower impact on infection rates than cross-neighborhood consumption. Simulations suggest the geographic restriction reduced COVID-19 cases by 17% versus an unrestricted scenario. These findings suggest geographically targeted stimulus policies can balance economic recovery with public health objectives.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The mobility dataset is proprietary to SK Telecom, and the dataset is subject to strict privacy regulations. The credit card consumption dataset is proprietary to BC Card and subject to privacy regulations. Both datasets were anonymized and aggregated before being shared with the authors. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Other datasets, including the official COVID-19 cases, are publicly accessible via Github at https://github.com/jieun0441/SP_Korea. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Due to the confidentiality of the data used in this study, the code will be shared in compliance with applicable data protection regulations, ensuring privacy. The publicly accessible code can be accessed via Github at https://github.com/jieun0441/SP_Korea. Additional custom code that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Anzai, A., Jung, S.-m. & Nishiura, H. Go To Travel campaign and the geographic spread of COVID-19 in Japan. BMC Infect. Dis. 22, 808 (2022).

Kanamori, R. et al. Changes in social environment due to the state of emergency and go to campaign during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: an ecological study. PLoS ONE 17, e0267395 (2022).

Baker, S. R., Farrokhnia, R. A., Meyer, S., Pagel, M. & Yannelis, C. Income, liquidity, and the consumption response to the 2020 economic stimulus payments. Rev. Finance 27, 2271–2304 (2023).

Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N. & Stepner, M. The economic impacts of COVID-19: evidence from a new public database built using private sector data. Q. J. Econ. 139, 829–889 (2024).

Guerrieri, V., Lorenzoni, G., Straub, L. & Werning, I. Macroeconomic implications of COVID-19: can negative supply shocks cause demand shortages? Am. Econ. Rev. 112, 1437–1474 (2022).

Angmo, S. in Virus Outbreaks and Tourism Mobility (ed. Kulshreshtha, S. K.) 15–30 (Emerald, 2021).

Anzai, A. & Nishiura, H. “Go To Travel” campaign and travel-associated coronavirus disease 2019 cases: a descriptive analysis, July–August 2020. J. Clin. Med. 10, 398 (2021).

Chudik, A., Pesaran, M. H. & Rebucci, A. Voluntary and Mandatory Social Distancing: Evidence on COVID-19 Exposure Rates from Chinese Provinces and Selected Countries Globalization Institute Working Paper number 382 (Dallas Fed, 2020).

Farboodi, M., Jarosch, G. & Shimer, R. Internal and external effects of social distancing in a pandemic. J. Econ. Theory 196, 105293 (2021).

Fowler, J. H., Hill, S. J., Levin, R. & Obradovich, N. Stay-at-home orders associate with subsequent decreases in COVID-19 cases and fatalities in the United States. PLoS ONE 16, e0248849 (2021).

Iacus, S. M. et al. Human mobility and COVID-19 initial dynamics. Nonlinear Dyn. 101, 1901–1919 (2020).

Shenoy, A. et al. God is in the rain: the impact of rainfall-induced early social distancing on COVID-19 outbreaks. J. Health Econ. 81, 102575 (2022).

Kim, S., Koh, K. & Lyou, W. Spend as you were told: evidence from labeled COVID-19 stimulus payments in South Korea. J. Public Econ. 221, 104867 (2023).

Kubota, S., Onishi, K. & Toyama, Y. Consumption responses to COVID-19 payments: evidence from a natural experiment and bank account data. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 188, 1–17 (2021).

Misra, K., Singh, V. & Zhang, Q. Frontiers: impact of stay-at-home-orders and cost-of-living on stimulus response: evidence from the CARES Act. Mark. Sci. 41, 211–229 (2022).

Feldman, N. & Heffetz, O. A grant to every citizen: survey evidence of the impact of a direct government payment in Israel. Natl Tax J. 75, 229–263 (2022).

Allcott, H. et al. Polarization and public health: partisan differences in social distancing during the coronavirus pandemic. J. Public Econ. 191, 104254 (2020).

Gollwitzer, A. et al. Partisan differences in physical distancing are linked to health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 1186–1197 (2020).

Dave, D., Friedson, A. I., Matsuzawa, K. & Sabia, J. J. When do shelter‐in‐place orders fight COVID‐19 best? Policy heterogeneity across states and adoption time. Econ. Inq. 59, 29–52 (2021).

Gupta, S. et al. Tracking public and private responses to the COVID-19 epidemic: evidence from state and local government actions. Am. J. Health Econ. 7, 361–404 (2021).

Wright, A. L., Sonin, K., Driscoll, J. & Wilson, J. Poverty and economic dislocation reduce compliance with COVID-19 shelter-in-place protocols. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 180, 544–554 (2020).

Zhang, R. Economic impact payment, human mobility and COVID-19 mitigation in the USA. Empirical Econ. 62, 3041–3060 (2022).

Kim, M. J. & Lee, S. Can stimulus checks boost an economy under COVID-19? Evidence from South Korea. Int. Econ. J. 35, 1–12 (2021).

Lee, K. O. & Lee, H. Public responses to COVID‐19 case disclosure and their spatial implications. J. Reg. Sci. 62, 732–756 (2022).

Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., Hendren, N., Stepner, M. & Team, T. O. I. How Did COVID-19 and Stabilization Policies Affect Spending and Employment? A New Real-time Economic Tracker Based on Private Sector Data Vol. 91 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020).

Kaplan, G., Moll, B. & Violante, G. L. The Great Lockdown and the Big Stimulus: Tracing the Pandemic Possibility Frontier for the US (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020).

Argente, D., Hsieh, C.-T. & Lee, M. The cost of privacy: welfare effects of the disclosure of COVID-19 cases. Rev. Econ. Stat. 104, 176–186 (2022).

Kontokosta, C. E., Hong, B. & Bonczak, B. J. Socio-spatial inequality and the effects of density on COVID-19 transmission in US cities. Nat. Cities 1, 83–93 (2024).

Brinkman, J. & Mangum, K. JUE insight: the geography of travel behavior in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Urban Econ. 127, 103384 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank SK Telecom and BC Card for providing us access to mobility and credit card transaction data, respectively. This work is supported by the Singapore Ministry of Education (MOE) Academic Research Fund (AcRF) Tier 1 Grant (A-0003825-01-00, K.O.L.). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.O.L. conceived and designed the study. J.E.L. analyzed the data. All authors wrote the first draft and provided critical revisions. All authors read and approved the submitted paper. All authors accessed and verified the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Cities thanks Mozhgan Pourmoradnasseri and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Summary of Data and Sources.

This figure shows various data types, sources, spatial- and time- units we employed for this study’s analyses.

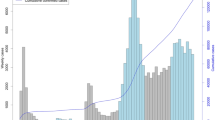

Extended Data Fig. 2 Temporal Trend of Card Transactions by Seoul Residents.

The height of bar graph shows trends in total number of card transactions in Seoul, which is sum of the stimulus payments transactions (red) and non-stimulus payments transactions (gray). The dashed line graph shows the percentage of the stimulus payments transactions in each week.

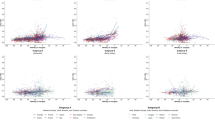

Extended Data Fig. 3 Trends of Stimulus and Non-Stimulus Transactions.

a, Event study results for all transactions. b, Event study results for non-stimulus transactions. Consistent with Extended Data Fig. 2, our analysis is limited to Seoul residents and focuses solely on physical transactions. We use the aggregate number of transactions rather than individual customer transactions. Data are presented as coefficient values (point estimate) +/- SE. (n = 16,540,750 transaction groups for a; n = 16,479,308 transaction groups for b) Transaction groups refer homogeneous transactions groups having the same O-D and occurred in the same week. Number of transactions in each observation was employed as a weight variable.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Pre- and Post-Stimulus Trends in Public Mobility.

a, Event study results of cross-neighbourhood mobility within Seoul, b, Event study results of cross-city mobility from non-Seoul, c, Weekly new infection rate per 100 K population of Seoul. Data are presented as coefficient values (point estimate) +/- SE. (n = 27,918 homogeneous trip groups with same O-D in each week). Panels a and b present temporal changes in commuting inflows to neighbourhoods in Seoul. In South Korea, the two days in the 18th week were Children’s Day and Mother’s Day, which are peak times for family trips and parent visits. However, the impact of these holidays on public mobility and seasonality is accounted for by the weekly fixed effects.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Discussions 1–4.

Supplementary Data 1

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 3.

Supplementary Data 2

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 4.

Supplementary Data 3

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 5.

Supplementary Data 4

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 6.

Supplementary Data 5

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 7.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J.E., Lee, K.O. & Lee, H. Geographic restrictions in stimulus spending mitigated COVID-19 transmission in Seoul. Nat Cities 2, 969–979 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-025-00318-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-025-00318-7