Abstract

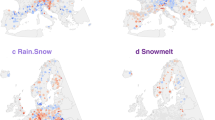

Flood fatalities remain a critical challenge in the Euro-Mediterranean region. This study analyses 2245 fatalities from 11 territories (1980–2020) using the FFEM-DB and global MSWEP rainfall datasets. Extreme rainfall is shown to be a significant risk factor, with fatal floods in many regions associated with rainfall exceeding the 99th percentile of daily values over 41 years. However, in some territories, fatalities also occurred under less severe rainfall, reflecting regional differences in exposure and vulnerability. In the South European-Mediterranean region (South EU-Med), deadly floods are triggered mainly by higher 24-hour rainfall than in the Central EU. Autumn is the most hazardous season, though summer floods in the South EU-Med demonstrate heightened exposure and impact severity. The findings are discussed in light of the climatology, geomorphology, and societal vulnerabilities, highlighting the importance of tailored management strategies to address regional disparities, particularly as climate change intensifies rainfall patterns across the Euro-Mediterranean region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rainfall-induced floods have significant socio-economic impacts worldwide. Over the last two decades, 44% of all recorded natural disasters were caused by floods, affecting millions and leading to vast economic losses1. Various factors influence the severity of the impact, enhancing populations’ exposure and vulnerability to flood risks2. As the climate crisis intensifies, international organisations like the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction3 and the European Commission (EU Floods Directive (2007/60/EC) have underscored the urgency of addressing flood risks. Their ongoing recommendations to the research community emphasise the need for more precise flood risk assessments and encourage nations to develop strategies to mitigate the socio-economic impacts of floods4.

In Europe, floods remain among the most damaging weather-related hazards, causing substantial societal impacts, including human fatalities5. Recent catastrophic events have shown the level of destruction and impact on human lives that floods can have across the continent6,7. The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015–2030) identifies primary goals of reducing mortality and improving disaster resilience. Besides, the systematic monitoring of disaster impacts, particularly flood fatalities, is crucial for tracking progress toward Sustainable Development Goals, such as SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 13 (Climate Action), which emphasize resilience-building and disaster risk reduction (DRR)8.

Human losses serve as a critical yet complex metric for assessing the direct impacts of flood events. While the number of deaths per event is often used to indicate flood severity, its interpretation requires consideration of broader disaster characteristics. Some events can be highly destructive in terms of economic losses without resulting in fatalities, while others cause disproportionate mortality despite moderate material damage. The presence of fatalities alone is frequently used as a qualitative threshold to classify floods as catastrophic9, highlighting the significance of human loss as a key impact factor. Consequently, reducing fatalities remains a central challenge for DRR efforts, as each death represents a failure of prevention or response systems10.

Flood-related mortality is driven by multiple interacting factors, including hydrometeorological conditions, geomorphology, land use, infrastructure, sociodemographics, and emergency response capacity11,12,13,14,15. While floodwater characteristics, such as inundation depth and flow velocity, are significant factors in determining the hazard severity, the absence of relevant data in many regions often requires researchers to rely on rainfall amounts as a necessary proxy for assessing flood hazard16,17. At the same time, rainfall has often been treated as an essential variable in flood impact analyses (e.g., see refs. 18,19).

Despite the critical role of rainfall as a primary driver of floods and their impacts, the relationship between rainfall characteristics and flood fatalities remains unexplored. Furthermore, many existing reports of flood fatalities rely on natural disaster databases such as EM-DAT20, which provide data on the number of deaths caused by major flood events. However, they overlook low-fatality flood events, which are more common in Europe21. As a result, while major disasters tend to dominate the focus of flood fatality research, the smaller-scale but more frequent events are underrepresented. By focusing on the full range of flood events, including those with lower mortality, we can better identify and define the critical rainfall thresholds contributing to flood fatalities.

This study addresses these gaps by analysing rainfall parameters, geomorphological and land use features, and seasonality to explore how these conditions are associated with flood fatalities (FF) in a Euro-Mediterranean region (Fig. 1) over 41 years from 1980 to 2020. The explorative analysis utilises two high-resolution datasets, i.e., the FFEM-DB21, which addresses the gaps in flood fatality research and existing data, often limited by small sample sizes, restricted geographic areas, low detail and exclusion of low-fatality events, and the Multi-Source Weighted-Ensemble Precipitation - MSWEP dataset, which is a global high-resolution precipitation product. A significant advantage of this study is that the FFEM-DB documents all recorded FF in the study area (Fig. 1) during the study period, with only a minimal possibility of missing cases21.

BAL Balearic Islands, CAT Catalonia, CYP Cyprus, CZE Czech. Republic, SFR Southern France, GER Germany, GRE Greece, ISR Israel, ITA Italy, POR Portugal, TUR Turkey, UK United Kingdom. (Original picture embedded from21. Created with QGIS 3.2 Python 3.4.).

The specific objectives of this study are multifold, with the overarching aim of examining and providing evidence that rainfall is a critical risk factor in flood fatalities across the Euro-Mediterranean region. That said, we first seek to assess the temporal and spatial context of rainfall events leading to flood fatalities, identifying any seasonality or regional patterns that may contribute to flood risk. Secondly, by comparing FF-causing rainfall with the heaviest rainfall patterns in the affected areas, we aim to contextualise these fatal flood events (FE) within the broader framework of extreme precipitation. Thirdly, we examine the geographical and geomorphological context—slope gradients and levels of urbanisation—across the affected territories, providing insights into how these factors may amplify the risk of flood events. Lastly, we conduct a frequency analysis of FF-causing rainfall. This frequency analysis is carried out separately for the central and southern European & Mediterranean regions, acknowledging these sub-regions distinct climatological and geographical characteristics and enhancing our understanding of region-specific flood hazards. Although this study does not include an analysis of human behaviour, we discuss relevant issues to help contextualise the findings.

Results

Descriptive statistics

After applying the defined rainfall thresholds as described in the Methods section, the dataset for the period 1980–2020 documents a total of 2245 FF resulting from 1157 FE across the examined European and Mediterranean territories. Turkey (TUR) is the most impacted region, with 285 recorded FE leading to 822 FF, while Cyprus (CYP) shows the lowest figures, with seven FE causing 13 FF (Fig. 2).

Table 1 summarises the mean, standard deviation (SD), minimum, and maximum values of rolling maximum rainfall over the various examined durations. The values across the dataset indicate that longer rainfall durations are generally associated with higher rainfall totals, with means of R3 = 22.4 mm, R6 = 35.8 mm, R12 = 53.2 mm, R24 = 73.1 mm, and R48 = 91.1 mm. This pattern, where longer durations correspond to higher rainfall totals, greater variability, and elevated maximum values, is consistent with expected rainfall dynamics and supports the methodological validity and robustness of the findings.

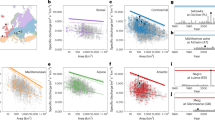

Correlation analysis

To further investigate the duration patterns of rainfall linked to FF at a regional level, i.e., the Central EU (UK, GER, CZE) and the South EU-Med (CYP, GRE, ISR, ITA, POR, TUR, CAT-BAL, and SFR), we examined the relationship between the maximum cumulative rainfall over two durations, the 2-day (R2d) and 4-day (R4d) (see Methods). The Spearman rank correlation coefficient (rho) between R2d and R4d was 23% lower for the Central EU (rho=0.69, p < 0.001) compared to the South EU-Med (rho=0.90, p < 0.001). The lower correlation in Central EU reflects a more significant disparity in rainfall totals across those time intervals and suggests more long-duration rainfall FE causing FF in these areas22,23. Prolonged rainfall events are more likely to be associated with fluvial flooding, resulting in a high cumulative R4d compared to R2d. By contrast, regions with higher rho values between R2d and R4d imply the totals across these two intervals are more similar; thus, rain accumulation occurs within a shorter duration, and these regions are likely to experience shorter, more intense rainfall events.

Weak but statistically significant relationships were found when examining the correlation between the number of FF per FE (impact severity) and the rolling maximum rainfall over the various examined durations. The rho coefficients ranged from 0.07 (p < 0.05) for R48 to 0.10 (p < 0.001) for R3 across the entire study area. Given this result and considering that 24 h rainfall is widely used in flood hazard research as a proxy for rainfall-induced flood risk16,17, we focus on R24 in the following analysis. This selection aligns with established research practices, facilitating comparability and interpretability within the broader context of flood hazard studies.

Cumulative patterns

The cumulative distribution of R24 associated with FF highlights significant regional differences (Fig. 3a). The CDF for Central EU accumulates at a lower R24 compared to South EU-Med, indicating that FF events in Central EU are associated with consistently lower R24 values. This may reflect the higher prevalence of prolonged FE in Central EU, where longer-duration events contribute to flood risk despite lower 24-h totals, as further supported by the multi-day rainfall analysis. Regarding the impact severity analysis (Fig. 3b), the CDF for FF per FE in Central EU shows accumulation at lower values, reflecting lower fatalities per event. These findings highlight that higher R24 amounts drive FE in the South EU-Med and tend to result in more severe impacts than those in the Central EU.

Rainfall distribution

The analysis of territorial and regional variations in R24 associated with FF reveals high geographic variability. The box-and-whisker plots in Fig. 4 (Central EU in blue and South EU-Med in orange) indicate clear distinctions emerging in mean values and data variability. Central EU exhibits the lowest mean R24 values, ranging from 51.9 mm in the UK to 53.7 mm in the CZE, with relatively low data variability (narrower boxes). Results suggest a higher consistency in rainfall intensity patterns associated with fatal flood events in the Central EU. A similar trend is observed in the far eastern territories of the South EU-Med, specifically TUR, CYP, and ISR. Here, the mean R24 values are slightly higher, ranging from 53.2 mm in Israel to 57.8 mm in CYP, again with comparably low data variability, indicating, at first glance, a similarity in FF-causing rainfall characteristics with Central EU despite the different geographical locations.

In contrast, the rest of the South EU-Med territories (the western-central part) show substantially higher means and variability in R24 values. In this sub-region, mean R24 values range from 69.4 mm in GRE to 123.5 mm in SFR, where the highest R24 values are observed. The more significant data variability in R24 observed in the western-central part of South EU-Med indicates that these areas are affected by a broader range of rainfall associated with FF. The lower ends of the R24 boxes in most of these territories overlap with the upper ranges seen in Central EU countries, suggesting that FE in these South EU-Med territories can occur at rainfall levels comparable to the highest levels observed in Central EU. Notably, SFR displays a distinctly higher R24 range, with the lower end of its box plot exceeding the upper quartiles of Central EU and far eastern South EU-Med territories (TUR, CYP, ISR).

To further contextualise the FF-causing rainfall values, p99 (99th percentile) box-and-whisker plots of the daily R24 distribution over the entire study period are illustrated in the plot (Fig. 4, with sienna colour). These p99 boxes are consistently narrower than the FF-causing R24 distributions, as the top 1% of all daily R24 values represent a truncated distribution with less variability, by definition. Across most territories, particularly in the Central EU and in the western-central part of the South EU-Med, especially in SFR, FF-causing R24 values tend to be relatively or significantly higher than the upper percentiles of the p99 rainfall distribution, indicating that fatal FE in these regions are predominantly associated with extreme rainfall events. In contrast, in the far eastern Mediterranean, the FF-causing R24 medians are more comparable to the median p99 values (TUR, ISR) or even much lower (CYP), suggesting that FF are not limited to extreme rainfall events in these territories.

Topographical and urban characteristics

The box plots of mean slope and urban share (Fig. 5) indicate that FE predominantly occurs in regions with gentle terrain and low urbanisation levels. Specifically, 75% of FE are located in areas with a mean slope of less than 4° and regions with less than 22% urbanisation. Among territories, ITA and CYP exhibit the highest mean slope values (4.2° and 4.3°, respectively) and data variability, suggesting that FE in these regions affect a broader range of topographies, including steeper terrains. In terms of urban share, there is substantial variability within and among territories. The UK, GER, POR, and CAT-BAL all show a high degree of variability in urban share. The UK stands out with the highest urban share profile for FE (mean = 28%), suggesting that flood risks may extend into more urbanised areas here compared to other regions.

No statistically significant difference is observed in impact severity (FF/FE) between highly urbanised areas (urban share > 50%) and less urbanised areas (urban share <50%). The mean impact severity is 1.8 FF/FE in urban areas and 1.6 FF/FE in non-urban areas (F = 0.98, chi2(1) = 0.66, p = 0.42). These findings are based on a dataset limited to high-accuracy locations, covering 63% of FE (see Methods for details). Turkey (TUR) is not included in this analysis due to the lower precision of reported locations. Additionally, data on urban categories were unavailable for Israel (ISR), limiting the analysis for this territory. To ensure that the exclusion of lower-accuracy records does not significantly alter the results or their interpretation, we also tested the analysis using the full dataset, confirming that the overall conclusions remained highly consistent.

Trends and seasonality

Regression analysis of FF-causing R24 at the daily scale over 41 years shows no statistically significant directional change for the entire study area or the Central EU and South EU-Med regions separately. A very weak but statistically significant positive trend (Poisson coef. < 0.06, p < 0.05) in the annual number of FF was detected in most territories, as well as for the entire study area in aggregate. No significant changes were found for GER, CAT-BAL, and TUR. For impact severity (FF/FE), annual patterns were generally statistically insignificant, except for GRE and UK, where very weak but statistically significant increases were found (Poisson coef. = 0.04, p < 0.05 in both cases). Fig. 6 shows FF and FE’s temporal trends for the entire study area using annual aggregates and 5-year moving averages (MA) to smooth short-term fluctuations. Fatalities peaked in the early 1990s (5-year MA reaching 83 FF), followed by a declining trend and stabilization. However, a renewed increasing trend emerged in the last decade, peaking in 2020 (80 FF). The 5-year MA of FE presents a smoother pattern with lower variability, exhibiting an increasing trend (Poisson coef. < 0.02, p < 0.001), also peaking in 2020 (51 FE).

Seasonal analysis across the study area highlights distinct patterns in rainfall, specifically the mean R24 and impact severity (namely the mean FF per FE) by season. For the entire study area, the mean R24 value is highest in autumn (92.2 mm) and lowest in spring (48.0 mm). Impact severity, however, is lowest in winter (1.4 FF per FE) and similar across other seasons, ranging from 1.9 to 2.1 FF per FE.

When examined by region, significant seasonal differences emerge (Fig. 7). In South EU-Med, autumn exhibits the highest mean R24 value (94 mm), followed by winter (71 mm), which aligns with the region’s seasonal rainfall climatology. In Central EU, the highest mean R24 value is recorded in summer (66 mm). Despite this, South EU-Med consistently shows higher impact severity across all seasons, with the most significant contrast in summer (2.7 FF per FE vs 1.4 in Central EU). Interestingly, the highest severity in South EU-Med occurs in summer, even though the mean R24 is approximately half that of autumn. This may reflect the influence of short-lived, high-intensity convective storms that dominate summer precipitation in the region, often producing severe localized impacts despite lower daily rainfall totals24,25.

Discussion

The analysis reveals significant regional disparities in rainfall patterns, exposure-related factors, and flood impacts across the studied Euro-Mediterranean region. While the study does not cover all of Europe, it provides insights into the rainfall-related fatal floods in the studied territories based on a detailed available dataset. The frequency distributions of R24 and impact severity indicate that FE in Central EU occur mainly at lower R24 thresholds and cause fewer deaths. The R24 difference may reflect the influence of longer-duration rainfall processes; however, R24 remains a consistent and comparable indicator across regions to explore rainfall intensity near the time of FE. Regarding the South EU-Med, between Portugal in the western Mediterranean and Greece in the eastern part of the basin, FF-causing R24 values are primarily associated with heavy or extreme rainfall events, as indicated by their relationship to the p99 values of the study period’s daily rainfalls. This connection demonstrates that a significant proportion of FE occur during periods of R24 comparable to the uppermost extremes, reinforcing its critical role as a driver of flood risk. Previous studies highlighted Southern Europe as a hotspot for extreme floods26,27. The above findings also align with previous literature identifying the region between Catalonia, south France and northern Italy as a high-impact area8,23,27 with relatively higher peak flows26,28,29. Exceptions were found for far eastern Mediterranean areas like Turkey, Israel, and Cyprus, where fatalities often occur under less severe rainfall conditions. These patterns may reflect inadequate flood defences, poor infrastructure, or heightened population exposure in these regions. While this study does not directly assess governance factors, our findings align with the literature indicating that institutional capacity, emergency planning, and risk awareness are key elements influencing flood fatality patterns across regions30,31.

Results show a higher prevalence of long-duration rainfall events leading to FF in the Central EU. Previous research emphasises the role of prolonged rainfall in triggering extensive riverine (fluvial) floods in Central Europe5,32, representing a significant hazard when they occur. In contrast, the South EU-Med demonstrates greater vulnerability to flash floods caused by severe, short-duration rainfall5,33,34. There is evidence that in Southern Europe, smaller catchments are more vulnerable to high-intensity short-duration storms, with spiky hydrographs, high slope values, rapid onset flooding, and high discharge peaks, in comparison to Central Europe, where lower slope values, larger catchment sizes, and lower peak discharges are more common26,35. Our findings also agree with Paprotny et al.27, who show the prevalence of river FF in the UK, Germany, and the Czech Republic, in contrast with the dominance of flash flood-induced fatalities in territories of Southern Europe. However, as shown, flash floods are not uncommon in Central EU. They exhibit distinct seasonality and are typically characterised by lower rainfall totals compared to those in Southern Europe36.

Seasonal patterns show autumn as the season with the highest rainfall, highlighting its role as a critical period for flood hazards37. The South EU-Med region faces heightened vulnerabilities across all seasons compared to the Central EU, particularly during summer. Despite occurring under less intense rainfall conditions, the elevated impact severity of summer floods points to increased exposure during this period. Summer activities such as tourism, outdoor work, and agriculture likely amplify risks, contributing to more significant fatalities when floods occur. Additionally, while higher rainfall thresholds are needed to trigger floods in South EU-Med, consequences are more severe when they happen, reflecting the interplay between extreme weather and human exposure.

Vulnerability factors further underscore the spatial heterogeneity of flood risks across the study region. Fatal flood events predominantly occurred in areas with gentle slopes (mean slope < 4°), aligning with findings that steeper slopes promote rapid surface flow, reduce infiltration time, and increase surface runoff, thereby limiting stormwater accumulation and ponding38. Fatal events were also more frequent in low urbanisation areas (urban share < 22%), highlighting vulnerabilities in rural and semi-rural regions, where limited flood defences, infrastructure, and evacuation options can exacerbate flood impacts39. However, compared to others, some regions, such as the UK and CAT-BAL, often experience events in more urbanised environments, likely due to extensive development along their coastal and inland areas, where managing floodwaters poses additional challenges in densely built settings. As urbanisation accelerates across Europe, cities will increasingly face heightened flood risks unless investments are made in adaptive infrastructure and drainage systems40,41.

Recent studies of disaster events suggest a broader decline in flood-related mortality attributed to risk reduction measures, such as improved risk awareness and structural flood defences42,43,44. Yet, the past three decades have been among the most flood-rich periods in Europe over the past 500 years, with changes in flood extent, seasonality, and air temperatures distinguishing them from previous flood-rich periods37. Our results indicate a persistence of fatal flood events in the study area, which underlines the need for continued investment in flood risk reduction and public awareness campaigns. It is important to emphasize why and how significant it is to consider low-mortality events for DRR. According to the frequency analysis results of the impacts’ severity, in both Central EU and South EU-Med, the overwhelming majority of the data are concentrated around a low number of victims per event. Studies on individual behaviour during floods show that the percentage of victims who exhibit “active behaviour”, meaning that they adopt a risky attitude towards the flood hazard, is higher in low-mortality events45,46. This suggests that human behaviour plays an essential role in shaping the fatal outcomes of floods, especially in less severe floods.

Global analyses demonstrate that flood vulnerability exhibits varying trends depending on socio-economic efforts, population distribution, and exposure, with both increases and decreases observed across countries, highlighting the complexity of flood risk projections47. Recent catastrophic events in Germany in 2021, Greece (‘Ianos’ in 202048, ‘Daniel’ in 2023), and Spain in 2024 illustrate the urgency of addressing these challenges. Rainfall totals of 150 mm in the Ahr Valley, Germany, 750 mm in Thessaly (‘Daniel), Greece and 300 mm in Valencia are among the extreme values identified in this study for the specific territories, stressing the growing severity of flood events. According to relevant studies, these disasters highlight vulnerabilities from inadequate preparedness, outdated flood risk maps, and infrastructure deficiencies49,50. Integrating these events into future analyses will help refine risk models and address the increasing frequency of extreme floods driven by climate change.

This study highlights rainfall as a critical flood hazard, with extreme R24 values driving fatal flood events in most regions. Tailored risk management strategies are needed to address regional disparities, as the intensifying impacts of climate change51 and factors such as extensive forest fires demand urgent updates to flood risk assessments, infrastructure, and public awareness. Expanding research across additional regions is vital to better understand the interplay between rainfall, exposure, and flood mortality, enhancing mitigation and preparedness efforts.

Methods

Material

The FFEM-DB (Database of Flood Fatalities from the Euro-Mediterranean Region) was the source of fatality data for this study, encompassing 2875 recorded flood fatalities (FF) from 11 territories (nine of which are entire countries) within the Euro-Mediterranean region for 41 years21. Specifically, the territories covered are Cyprus (CYP), the Czech Republic (CZE), Germany (GER), Greece (GRE), Israel (ISR), Italy (ITA), Portugal (POR), Turkey (TUR), the United Kingdom (UK), the Spanish regions of Catalonia (CAT) and Balearic Island (BAL) and the southern region of France (SFR) (Fig. 1). The study territories are covered in their entirety; thus, the FFEM-DB includes all recorded FFs in these areas during the study period, with only a minimal possibility of missing cases21.

The FFEM-DB database provides comprehensive details on each fatality, including victim profiles, the circumstances and the place of death, along with its corresponding geographical coordinates. The geographical information varies in precision, consisting of exact latitude and longitude coordinates, approximated locations, or the central coordinates of municipalities (classified as Territory 3 level in the database). This variability in location data facilitated the spatial analysis of rainfall and its association with FF, allowing for regional comparisons and assessments of geographical distribution.

The rainfall data were extracted from the MSWEP (Multi-Source Weighted-Ensemble Precipitation). The MSWEP is a global precipitation dataset combining various sources to provide accurate rainfall estimates at high spatial (0.1 × 0.1 deg) and temporal (3-h) resolutions available from 1979. It integrates precipitation data from several sources, including satellite data (e.g., TRMM and GPM), ground-based measurements from rain gauges, and reanalysis datasets (e.g., ERA5, MERRA-2). This multi-source approach ensures a robust and consistent representation of precipitation patterns over extended periods. MSWEP allows for the alignment of rainfall data with the geographical locations of FF, facilitating detailed analyses of the rainfall characteristics associated with these events. At this point, it should be mentioned that although the MSWEP dataset provides accurate rainfall estimates, it cannot reproduce the local maxima of rainfall events as they could have been recorded by in situ rain gauges. This limitation affects our study, possibly resulting in lower rainfall values. On the other hand, this same dataset offers the possibility of consistently analysing the whole study area.

The CORINE Land Cover dataset was used to extract land use and geomorphological data to contextualise the environmental factors characterizing the locations of the FF. Regarding land use, urban areas classified under CORINE codes 111, 112, and 121 (continuous urban fabric, discontinuous urban fabric, and industrial or commercial units, respectively) were selected to define the urban share. Data on urban categories were unavailable for Israel (ISR).

Data elaboration

The rainfall conditions associated with each FF were estimated through a multi-step process that involved calculating the rolling maximum rainfall over various time intervals. The first step was to extract data points corresponding to each fatality’s latitude, longitude and date of the incident from the MSWEP dataset. This approach ensured the analysis was spatially and temporally aligned with the recorded FF and the corresponding fatal flood events (FE). We define FE as an event occurring within a specific municipality on a given date, resulting in one or more flood fatalities.

A spatial window with a 0.15-degree radius was created for each extracted point, encompassing an area approximately equivalent to a 4 × 4 grid. This window allowed for the consideration of nearby variations in rainfall data. Additionally, a temporal window covering five days was established, including three days before the incident, the incident date and one day following it. This temporal scope enabled the analysis to capture rainfall patterns and accumulations leading up to and shortly after the FE.

Within these spatial and temporal windows, precipitation data were processed to calculate rolling maximum rainfall over several time intervals (3 h (R3), 6 h (R6), 12 h (R12), 24 h (R24), and 48-h (R48). For each time interval, the maximum rolling rainfall was identified and linked to the geolocation of the FF. This method provided a systematic framework for analysing rainfall intensity across different durations, ensuring consistency in evaluating potential contributions to flood fatalities. Accordingly, for each FE, the maximum rainfall for each interval was calculated from the individual rainfall values linked to the fatalities of the FE.

Additionally, to explore rainfall duration patterns in relation to FE, we also extracted the FF-causing daily R24 values for each of the five days in the temporal window (i.e., three days before the incident, the day of the event, and one day after). Based on these daily values, we then calculated the maximum cumulative rainfall totals over 2-day (R2d) and 4-day (R4d) periods within the same window. These aggregated metrics enabled the assessment of whether rainfall associated with fatalities was concentrated over shorter or longer periods, providing deeper insight into the temporal dynamics of rainfall linked to fatal flood events across different regions.

A rainfall threshold was established to refine the dataset and focus on significant rainfall events. Specifically, an R24 or R48 threshold of 20 mm was applied. This criterion effectively narrowed the dataset to 2245 flood fatalities (78% of the FFEM-DB records), ensuring that the analysis centred on events where rainfall was likely a major contributing factor. By applying this threshold, the study also aimed to minimise the influence of potential discrepancies in reported incident locations or dates and limitations in capturing localised rainfall patterns. This approach helped maintain the robustness of the analysis by focusing on substantial rainfall events that were more reliably represented in the datasets.

Geomorphological data and land use characteristics were analysed within a 2.5 km radius of each fatality. Key variables included slope, urban share, and distance from a water source. The urban share data were adjusted to align with the dates of the fatal incidents, ensuring an accurate temporal representation, while sea surface areas were excluded from these calculations to prevent skewed data. However, the analysis faced limitations regarding water sources, as the CORINE dataset does not comprehensively cover all rivers or streams, and certain hydrological persistence data remained unavailable or outdated for drainage systems. Therefore, hydrological data such as stream length and type of persistence were not considered.

To ensure the reliability of the mean slope and urban share analyses, we applied a filtering process to exclude records with low location precision. Specifically, we removed records where the reported location was classified as approximated or as the central coordinates of a municipality (Territory 3 level in the database) unless the municipality’s total area was less than 19 km². This threshold aligns with the 2.5 km radius used to calculate the mean slope and urban share around each reported flood fatality location. The slope and urbanisation analysis dataset now includes 63% of all FE (734 out of 1157) and 52% of FF (1178 out of 2245), providing a refined sample with high location accuracy. Turkey (TUR) was excluded from this analysis, as 98% of FF locations were reported only at the municipality centroid level, where the large administrative areas (higher than 20 km²) introduce significant uncertainty in slope and urbanisation estimates.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were employed to summarise data across the study period, providing an overview of central tendencies, variability, and overall patterns. We performed Spearman correlation analysis between rainfall parameters to assess regional patterns in rainfall durations and identify areas where long-duration events occur. A linear regression analysis was applied to evaluate trends in FF-causing R24, using daily observations over 41 years to detect any directional changes. Poisson regression was applied to examine annual trends in FF and FE, accounting for variations over time in count data. The p-values are set at a significance threshold of 0.05. Cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) were constructed to assess the regional differences in R24 causing FF and the impact severity (FF per FE) distributions. Further, ANOVA was applied to analyse seasonal variations and patterns of rainfall and their potential impact on flood fatalities.

Box and Whisker Plots distributions served a dual purpose. First, to illustrate the distribution and variability of rainfall amounts in different territories, highlighting outliers and identifying patterns possibly associated with flood deaths. Second, to compare the 24 h rainfall, R24, related to flood fatalities with the heaviest rainfall amounts that typically occur in those same locations over the past 41 years. For this comparison, daily rainfalls over 1.0 mm were extracted for the period 1980–2020 for the location of each flood fatality event, using the same methodology applied to extract the fatality-related rainfall parameters. The 99th percentile (p99) of daily R24 values was used as a benchmark, a threshold representing the heaviest rainfall in these areas.

We conducted the statistical analyses at the territorial or regional levels, contrasting patterns between the Central European (UK, GER, CZE; referred to as Central EU in this study) and Southern Mediterranean European regions (CYP, GRE, ISR, ITA, POR, TUR, CAT-BAL, and SFR; referred to as EU-Med in this study) under examination. This regional segmentation reflects inherent differences in climatological and meteorological conditions and geographical locations52,53. These climatic contrasts shape rainfall events’ intensity, duration, and seasonality, which is essential in understanding the diverse flood hazards across the study area26,54. The division between Central EU and Southern EU-Mediterranean used in this study is a pragmatic grouping designed to facilitate the analysis and interpretation of results. It does not represent a strict climatic classification but rather reflects a functional categorization informed by geographic proximity and broad climatic and socio-economic characteristics relevant to the studied territories.

Data availability

The underlying code (and links to the raw data sources) and the dataset developed for this study are available in 4TU.ResearchData. They can be accessed via https://data.4tu.nl/datasets/711991db-d803-4388-8b0e-72893b314533.

Code availability

The underlying code (and links to the raw data sources) are available in 4TU.ResearchData. They can be accessed via https://data.4tu.nl/datasets/711991db-d803-4388-8b0e-72893b314533.

References

CRED-UNDRR. The human cost of disasters: An overview of the last 20 years (2000–2019). Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters—UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. https://cred.be/sites/default/files/adsr_2019.pdf (2020).

Tellman, B. et al. Satellite imaging reveals increased proportion of population exposed to floods. Nature 596, 80–86 (2021).

UNDRR, Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2024. https://www.undrr.org/gar/gar2024-special-report (2024).

UNDRR. Main findings and recommendations of the midterm review of the implementation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. http://sendaiframework-mtr.undrr.org/quick/76209 (2023).

Paprotny, D., Terefenko, P. & Śledziowski, J. HANZE v2.1: an improved database of flood impacts in Europe from 1870 to 2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 5145–5170 (2024).

Fekete, A. & Sandholz, S. Here Comes the Flood, but Not Failure? Lessons to Learn after the Heavy Rain and Pluvial Floods in Germany 2021. Water 13, 3016 (2021).

Wise, J. Spanish floods: Experts call for clearer warnings. BMJ 387, q2421. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.q2421 (2024).

Stamos, I. & Diakakis, M. Mapping Flood Impacts on Mortality at European Territories of the Mediterranean Region within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Framework. Water 16, 2470 (2024).

Gil-Guirado, S., Pérez-Morales, A. & Lopez-Martinez, F. SMC-Flood database: a high-resolution press database on flood cases for the Spanish Mediterranean coast (1960–2015). Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 19, 1955–1971 (2019).

Diakakis, M. et al. An integrated approach of ground and aerial observations in flash flood disaster investigations: The case of the 2017 Mandra flash flood in Greece. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 33, 290–309 (2019).

Han, Z. & Sharif, H. O. Analysis of flood fatalities in the United States, 1959–2019. Water 13, 1871 (2021).

Jonkman, S. N. & Kelman, I. An analysis of the causes and circumstances of flood disaster deaths. Disasters 29, 75–97 (2005).

Petrucci, O. Factors leading to the occurrence of flood fatalities: a systematic review of research papers published between 2010 and 2020. Nat. hazards earth Syst. Sci. 22, 71–83 (2022).

Petrucci, O. et al. Flood Fatalities in Europe, 1980–2018: Variability, Features, and Lessons to Learn. Water 11, 1682 (2019).

Salvati, P. et al. Gender, age and circumstances analysis of flood and landslide fatalities in Italy. Sci. total Environ. 610, 867–879 (2018).

Cortès, M., Turco, M., Llasat-Botija, M. & Llasat, M. C. The relationship between precipitation and insurance data for floods in a Mediterranean region (Northeast Spain). Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 857–868 (2018).

Papagiannaki, K. et al. Identification of Rainfall Thresholds Likely to Trigger Flood Damages across a Mediterranean Region, Based on Insurance Data and Rainfall Observations. Water 14, 994 (2022a).

Esbrí, L., Rigo, T., Llasat, M. C. & Aznar, B. Identifying Storm Hotspots and the Most Unsettled Areas in Barcelona by Analysing Significant Rainfall Episodes from 2013 to 2018. Water 13, 1730 (2021).

Saharia, M. et al. On the impact of rainfall spatial variability, geomorphology, and climatology on flash floods. Water Resour. Res. 57, e2020WR029124 (2021).

Guha-Sapir, D., Below, R. & Hoyois, P. EM-DAT: The CRED/OFDA International Disaster Database. www.emdat.be (2021).

Papagiannaki, K. et al. Developing a large-scale dataset of flood fatalities for territories in the Euro-Mediterranean region, FFEM-DB. Sci. Data 9, 166 (2022b).

Cipolla, G., Francipane, A. & Noto, L. V. Classification of Extreme Rainfall for a Mediterranean Region by Means of Atmospheric Circulation Patterns and Reanalysis Data. Water Resour. Manag. 34, 3219–3235 (2020).

Gaume, E. et al. Mediterranean extreme floods and flash floods. The Mediterranean Region under Climate Change. A Scientific Update, IRD Editions, pp.133-144, Coll. Synthèses, 978-2-7099-2219-7. ffhal-01465740v2 (2016).

Michaelides, S. et al. Reviews and perspectives of high impact atmospheric processes in the Mediterranean. Atmos. Res. 208, 4–44 (2018).

Taszarek, M. et al. A Climatology of Thunderstorms across Europe from a Synthesis of Multiple Data Sources. J. Clim. 32, 1813–1837 (2019).

Gaume, E. et al. A compilation of data on European flash floods. J. Hydrol. 367, 70–78 (2009).

Paprotny, D., Sebastian, A., Morales-Nápoles, O. & Jonkman, S. N. Trends in flood losses in Europe over the past 150 years. Nat. Commun. 9, 1985 (2018).

Amponsah, W. et al. Integrated high-resolution dataset of high-intensity European and Mediterranean flash floods. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 1783–1794 (2018).

Llasat, M. C. et al. High-impact floods and flash floods in Mediterranean countries: the FLASH preliminary database. Adv. Geosci. 23, 47–55 (2010).

Barriendos, M. et al. Climatic and social factors behind the Spanish Mediterranean flood event chronologies from documentary sources (14th–20th centuries). Glob. Planet. Chang. 182, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2019.102997 (2019).

Pérez Morales, A., Gil Guirado, S. & Olcina Cantos, J. Housing bubbles and the increase of flood exposure. Failures in flood risk management on the Spanish south-eastern coast (1975–2013). J. Flood Risk Manag. 11, 1–12 (2015).

Steinhausen, M. et al. Drivers of future fluvial flood risk change for residential buildings in Europe. Glob. Environ. Change 76, 102559 (2022).

Drori, R., Ziv, B., Saaroni, H., Etkin, A. & Sheffer, E. Recent changes in the rain regime over the Mediterranean climate region of Israel. Climatic Change 167, 15 (2021).

Lionello, P. & Giorgi, F. Winter precipitation and cyclones in the Mediterranean region: future climate scenarios in a regional simulation. Adv. Geosci. 12, 153–158 (2007).

Kuentz, A., Arheimer, B., Hundecha, Y. & Wagener, T. Understanding hydrologic variability across Europe through catchment classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 2863–2879 (2017).

Brázdil, R. et al. Spatiotemporal variability of flash floods and their human impacts in the Czech Republic during the 2001–2023 period. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 24, 3663–3682 (2024).

Blöschl, G. et al. Current European flood-rich period exceptional compared with past 500 years. Nature 583, 560–566 (2020).

Li, X. et al. A Study of Rainfall-Runoff Movement Process on High and Steep Slopes Affected by Double Turbulence Sources. Sci. Rep. 10, 9001 (2020).

Diakakis, M. Characteristics of infrastructure and surrounding geo-environmental circumstances involved in fatal incidents caused by flash flooding: evidence from Greece. Water 14, 746 (2022).

Andreadis, K. M. et al. Urbanizing the floodplain: global changes of imperviousness in flood-prone areas. 2022 Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 104024 (2022).

Feyen, L., Dankers, R., Bódis, K., Salamon, P. & Barredo, J. I. Fluvial flood risk in Europe in present and future climates. Climatic change 112, 47–62 (2012).

Formetta, G. & Feyen, L. Empirical evidence of declining global vulnerability to climate-related hazards. Glob. Environ. Change 57, 101920 (2019).

Jonkman, S. N., Curran, A. & Bouwer, L. M. Floods have become less deadly: an analysis of global flood fatalities 1975–2022. Nat. Hazards 120, 6327–6342 (2024).

Merz, B. et al. Causes, impacts and patterns of disastrous river floods. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 592–609 (2021).

Diakakis, M. et al. How different surrounding environments influence the characteristics of flash flood-mortality: The case of the 2017 extreme flood in Mandra, Greece. J. Flood Risk Manag. 13, e12613 (2020).

Vinet, F., Lumbroso, D., Defossez, S. & Boissier, L. A comparative analysis of the loss of life during two recent floods in France: The sea surge caused by the storm Xynthia and the flash flood in Var. Nat. Hazards 61, 1179–1201 (2012).

Tanoue, M., Hirabayashi, Y. & Ikeuchi, H. Global-scale river flood vulnerability in the last 50 years. Sci. Rep. 6, 36021 (2016).

Lagouvardos, K., Karagiannidis, A., Dafis, S., Kalimeris, A. & Kotroni, V. Ianos—A Hurricane in the Mediterranean. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 103, 1621–1636 (2022).

Faranda, D., Alvarez-Castro, M. C., Ginesta, M., Coppola, E. & Pons, F. M. E. Heavy precipitations in October 2024 South-Eastern Spain DANA mostly strengthened by human-driven climate change. ClimaMeter. Inst. Pierre Simon Laplace, CNRS. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14052042 (2024).

Rhein, B. & Kreibich, H. Causes of the exceptionally high number of fatalities in the Ahr valley, Germany, during the 2021 flood. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 25, 581–589 (2025).

Tradowsky, J. S. et al. Attribution of the heavy rainfall events leading to severe flooding in Western Europe during July 2021. Climatic Change 176, 90 (2023).

Eiras-Barca, J. et al. European West Coast atmospheric rivers: A scale to characterize strength and impacts. Weather Clim Extremes 31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2021.100305 (2021).

Rivoire, P., Le Gall, P., Favre, A. C., Naveau, P. & Martius, O. High return level estimates of daily ERA-5 precipitation in Europe estimated using regionalized extreme value distributions. Weather Clim. Extremes 38, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2022.100500 (2022).

Mediero, L. et al. Identification of coherent flood regions across Europe by using the longest streamflow records. J. Hydrol. 528, 341–360 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work has been partially supported by the DataGEMS project, funded by the European Union's Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No. 101188416. The authors also acknowledge the availability of the MSWEP database, which was essential for the rainfall analysis conducted in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.P., V.K., and K.L. designed the research. K.P. analysed the data & prepared the figures. K.P., V.K., K.L. and M.D. wrote the main manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript. P.K. developed the codes to extract MSWEP and extracted Corine Land Cover data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Papagiannaki, K., Kotroni, V., Lagouvardos, K. et al. Rainfall patterns and their association with flood fatalities across diverse Euro-Mediterranean regions over 41 years. npj Nat. Hazards 2, 39 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00095-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00095-2

This article is cited by

-

Deformation monitoring and spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of Jungong landslide based on InSAR technology

npj Natural Hazards (2025)

-

Mortality Related to Climate Change and Environmental Hazards in the Mediterranean Region: A Scoping Review

Current Environmental Health Reports (2025)