Abstract

Under the influence of factors such as climate and land use changes, it is highly useful to investigate the spatio-temporal occurrence characteristics of forest fires using remote sensing data. This study utilized long-term remote sensing data on Active Fire Spots (AFSs), Burned Areas (BA), and Land Cover Types (LCT) in Yunnan Province. Through pixelization of AFSs, spatial extraction, and spatio-temporal clustering, 39,101 Forest Fire Events (FFEs) were identified. The results indicate that FFEs in Yunnan Province exhibit spatio-temporal clustering, with an overall annual fluctuating decline trend. The clustering is more pronounced in spring and winter, with a delayed temporal span. Over 88% of FFEs are concentrated in southern Yunnan, and the frequent occurrence areas have shifted eastward in recent years. This study deepens the understanding of the spatio-temporal dynamics of forest fires and provides a basis for regional forest fire management to promote sustainable development in related fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As an integral component of natural ecological processes, forest wildfires—when left uncontrolled—have emerged as a pressing global environmental challenge1. These disasters not only result in sharp declines in forest area and severe structural damage2,3, but also disrupt ecosystem functions4 and pose substantial risks to human societies5,6. Under the compounded influence of intensified climate change7, increasing anthropogenic activities, and land-use transformations, forest fires worldwide are exhibiting new characteristics, including increased frequency and Burned Area (BA)8,9,10,11, as well as extended fire seasons10,12. Consequently, the spatio-temporal characteristics of forest fires are undergoing marked transformations13,14,15.

Research into the spatio-temporal characteristics of forest fires aims to uncover the frequency and distributional patterns of fire occurrences at specific spatial and temporal scales. Evidence shows that forest fires do not occur randomly but instead demonstrate significant spatio-temporal clustering16,17. For instance, seasonal variations in climate exacerbate wildfire severity in the western United States15; regional susceptibility to wildfires varies in extent18; and fire intensity has been increasing in central Siberia and eastern regions11. These observations underscore the widespread and profound adverse impacts that increasingly severe forest fire regimes exert on ecological systems and sustainable development across regional and even global scales, including elevated carbon emissions19, acceleration of climate warming20, threats to forest watersheds and drinking water quality21, deterioration of air quality22, and alterations in soil properties23. Accordingly, this study selects Yunnan Province in southwestern China—a region with frequent forest fires—as the study area.

Remote sensing has become an indispensable tool for studying the spatio-temporal characteristics of forest fires, owing to its capacity to provide standardized, long-term fire records across regional or global scales. Depending on the fire phase (pre-fire, active fire, and post-fire), two types of data can be obtained: Active Fire (AF) data during the fire, and BA data following the fire. Currently, widely used AF products include the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Collection 624 and the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) V125, which provide key fire-related information such as location, ignition time, and Fire Radiative Power (FRP), with spatial and temporal resolutions ranging from 1000 m to 250 m and 12 h to 24 h, respectively. BA products, on the other hand, are categorized by spatial resolution into coarse (>1000 m), moderate (250~1000 m), and high-resolution classes (~30 m), offering BA data that are essential for quantifying fire trends and patterns, as well as for assessing the impacts of fires on a variety of natural and social systems26,27,28. Among them, MODIS MCD14ML is widely adopted in spatio-temporal wildfire research due to its extended temporal coverage (since 2000), moderate resolution (1000 m × 1000 m; ~12 h), and reliable fire occurrence information.

Nonetheless, MODIS MCD14ML AF product exhibits several limitations. First, most studies adopt a high-confidence threshold (typically confidence ≥ 80%) to screen AF Spots (AFSs), which enhances reliability but simultaneously excludes low-confidence detections—often associated with low-FRP fires or small fires—thus, potentially leading to underestimation of fire-related indicators28,29. This exclusion hampers the investigation of fire characteristics in high-latitude cold regions, cloudy mountainous terrains, or low-biomass landscapes such as croplands and grasslands. To address this, the Fire Information Resource Management System (FIRMS) recommends selecting an appropriate confidence threshold based on empirical approach30. Li et al.11, through mathematical derivation, identified AFSs with confidence > 35% as suitable for studying fire intensity in pan-Arctic forests. Second, the moderate spatial resolution of MCD14ML continues to affect the accuracy of fire distribution. The actual detection footprint is shaped by both the satellite’s orbital track and scan direction, often exceeding the nominal pixel size (1000 m × 1000 m), and may contain multiple independent fires or false detections (e.g., smoke plumes or reflective metal roofs) within a single pixel24,30. Furthermore, most existing studies focus on the frequency of discrete Forest Fire Spots (FFSs) rather than complete and independent Forest Fire Events (FFEs), limiting the accuracy of FFEs statistics and the estimation of fire behavior characteristics such as BA and fire spread rate31. Where studies do adopt event-based approaches, they tend to focus on typical or large-scale forest fires, neglecting weak and short-duration forest fires that are most frequent28,32.

The cross-validation of AF and BA datasets provides a promising pathway to address these deficiencies. Specifically, srences in sensor hardware (e.g., spectral sensitivity, spatial resolution, instantaneous field of view), orbital configuration (e.g., revisit time, temporal resolution), and data processing algorithms (e.g., fire detection algorithms, reprocessing routines)33,34 result in remote sensing data of the same forest fire events exhibiting distinct spatio-temporal characteristics. Hence, using high-resolution BA data to spatially filter other fire products can enhance the accuracy of identifying the same forest fire events. Fornacca et al.28 demonstrated that integrating AF and BA products significantly improves the producer’s accuracy (PA) of small fire detection. Similarly, Li et al.35 utilized 250 m-resolution BA data to construct a long-term, high-resolution emission inventory of Open Biomass Burning (OBB) across a regional scale.

In summary, this study employs MODIS MCD14ML data alongside high-resolution BA datasets to extract a maximal set of valid FFSs and aggregate them into complete and independent FFEs. By analyzing their occurrence patterns across multiple spatio-temporal scales, this research aims to provide robust insights for forest fire management in Yunnan Province.

Results

Through a series of processing steps applied to AF spots in Yunnan Province from 2001 to 2021, a total of 39,101 FFEs were identified. These included 14,154 Clustered FFEs (CFFEs, MinPts ≥2) and 24,947 Isolated FFEs (IFFEs, MinPts = 1). Based on this dataset, the distributions and durations of FFEs, CFFEs, and IFFEs were examined across multiple spatio-temporal dimensions, as detailed below:

At the spatial scale, we first analyze the spatial distribution characteristics of FFSs, FFEs, CFFEs, and IFFEs in the five major subregions of the province from 2001 to 2021. We extract a central coordinate point from multiple forest fire points included in CFFEs for display. Next, we analyze the spatiotemporal dynamics of FFEs in the province for each year and draw corresponding charts to illustrate the results.

On a temporal scale, analyze the temporal distribution characteristics of FFEs across years, months, and seasons (including the four traditional seasons and the 24 solar terms) in Yunnan Province, and create a temporal distribution table to visualize and analyze the results.

In terms of duration, this study analyzed the annual and monthly distribution of FFEs with different durations (0.5–6 days) across Yunnan Province and its five major subregions. The duration was determined based on the revisit interval (~12 h per revisit) of the Terra/Aqua dual-satellite system when AFSs were detected. FFEs with only one forest fire spotst and time record were classified as short-duration forest fire events (FFEs, duration < 0.5 day). While CFFEs are further categorized into short-duration forest fires (duration < 0.5 days) or long-duration forest fires (duration ≥0.5 days) based on their duration, with corresponding charts and explanations of the research results provided.

Spatial characterization

Provincial scale

By applying Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) to the four types of forest fires identified in Yunnan Province between 2001 and 2021, see Fig. 1, this study aims to elucidate their overall spatial distribution characteristics. Specifically, Fig. 1a illustrates FFSs prior to spatio-temporal clustering, while Fig. 1b presents FFEs after clustering, and Fig. 1c, d further delineate CFFEs and IFFEs, respectively.

Overall, all four types of forest fires exhibit broadly similar spatial patterns, with high concentrations occurring in southeastern, southwestern, and portions of central Yunnan36; however, the latter three classifications, especially post-clustering representations, more accurately capture the practical spatial characteristics of fire occurrence. Notably, the maximum density value of FFEs, which indicates areas susceptible to forest fires, has been reduced to 0.8—half the value observed for FFSs—thereby providing a more refined and statistically robust foundation for subsequent multi-scale spatio-temporal analyses. For instance, both FFSs and FFEs reveal spatial misalignments in identifying fire-prone areas in northwestern Yunnan; however, while FFSs density may partially reflect the spatial distribution of local fires, it introduces notable statistical errors when used to characterize complete and discrete fire events. Consequently, regions historically prone to forest fires in northwestern Yunnan should be reattributed to areas such as Lijiang, bordering Sichuan Province (Fig. 1b), rather than Dali, which exhibits higher fire point densities but less actual fire event occurrence (Fig. 1a).

Although both CFFEs (Fig. 1c) and IFFEs (Fig. 1d) identify subregions with notably high frequencies of FFEs between subregions, their spatial characteristics differ. First, the forest fire-prone areas identified by CFFEs have lower density values (0.2684) and are spatially concentrated and contiguous, while the high-frequency forest fire areas identified by IFFEs have higher density values (0.4694) and exhibit more pronounced clustering in localized regions. Additionally, this type of fire is often overlooked in other studies but is actually the most frequent type of forest fire. Therefore, the FFEs, which combine CFFEs and IFFEs, demonstrate more realistic regional clustering and statistical accuracy (Fig. 1b).

Major subregions

The annual trends in FFEs across the five major subregions of Yunnan Province vary significantly, as shown in the line charts for each subregion in Fig. 2 (corresponding to the left axis). It is important to note that between November 1999 and August 2002, only one satellite sensor (Terra/MODIS) was available to monitor FFSs globally, which resulted in the number of Active Fire spots being nearly halved compared to the initial period of MODIS dual-constellation integration starting in August 2002, thus mistakenly making 2001 appear as the year with the fewest fire events in Yunnan Province. As a result, these two years (2001 and 2002) should be excluded from subsequent spatio-temporal analyses.

In terms of regional statistical results, forest fires in the southeastern and southwestern parts of Yunnan have been highly prominent throughout all years, exhibiting significant interannual fluctuations that strongly influence the overall interannual trends at the provincial level. The annual average number of fires was ~800, with 802 in the southeastern part and 782 in the southwestern part. The extreme values in southeastern Yunnan occurred in 2010 (High: 2367) and 2011 (Low: 147), accounting for 53.6% and 21.3%, respectively, of the total FFEs incidents in those years. In southwestern Yunnan, the highest and lowest values were recorded in 2004 (High: 2332) and 2018 (Low: 162), accounting for 67.4% and 18.9% of the total FFEs events in those years, respectively. Afterward, the incidence continued to fluctuate annually but began to stabilize around 2015. In contrast, the fluctuations of FFEs in the northeastern, central, and northwestern subregions of Yunnan were relatively mild, with annual averages of ~57, 127, and 226 FFEs events, respectively. Peak FFEs values across these three subregions occurred in 2010, influenced by the El Niño phenomenon, with substantial fluctuations occurring during the prolonged drought period from 2012 to 201437. Notably, northwestern Yunnan, more vulnerable to extreme weather conditions, experienced greater fluctuations in FFEs occurrences during these years38, nearly double that of the other subregions (northeastern and central Yunnan).

Finally, considering the overall trend of the statistical results, the incidence of forest fires across all subregions exhibited a fluctuating decline over the years, with a stabilization occurring between 2017 and 2021.

In the visualization of the annual FFEs’ kernel density across Yunnan Province, the spatial distribution and changing trends between subregions are more clearly evident, Fig. 3. Between 2001 and 2013, FFEs in Yunnan Province were significantly concentrated in the southwestern regions of Xishuangbanna and Pu’er, as well as the southeastern regions of Honghe and Wenshan, located between 21°N and 25°N. The average annual FFEs density value was 0.0486, maintaining a relatively high level throughout this period. Over time, the FFEs high-incidence zones in southwestern Yunnan showed a trend of gradual reduction, while the FFEs high-incidence zones in southeastern Yunnan exhibited a trend of gradual expansion, reaching a peak density difference of 0.0763 in 2010.

Between 2014 and 2021, the centers of the FFEs high-incidence zones shifted significantly eastward to the southeastern Yunnan subregion. Although some years, such as 2018, saw significant interannual fluctuations in southwestern Yunnan, the overall trend showed a decrease and contraction in the high-incidence areas of FFEs across the province, which became more concentrated in the Pu’er region of southwestern Yunnan. The average annual FFEs density value in this region decreased to 0.0364, reflecting a 25% reduction compared to the 2001–2013 period. As the region most severely affected by forest wildfires during the past three years (2019–2021), the southeastern Yunnan region has also experienced shifts in its FFEs high-incidence zones. Overall, these zones are contracting horizontally while expanding vertically towards the south, forming a spindle-like shape, indicating that the regional clustering characteristics of forest fires in southeastern Yunnan are both prominent and widespread.

Temporal characterization

Annual analysis

From 2001 to 2021, the annual FFEs in Yunnan Province exhibited pronounced interannual variability and distinct seasonal distribution patterns, as illustrated in Fig. 4. The interannual variation of FFEs is shown in Fig. 4a, the annual extremes in FFEs incidence occurred consecutively in 2010 and 2011, exerting a notable influence on the subsequent temporal distribution of FFEs and marking 2010 as a critical turning point in the long-term trend. Prior to 2010, excluding the data-limited years of 2001 and 2002, the province experienced a seven-year period (2003–2010) during which the number of FFEs exceeded 2000 annually, with an average of 2698 events per year, indicating a persistently high incidence rate. In contrast, between 2011 and 2021, the average annual number of FFEs declined to 1359, representing a 49.6% reduction compared to the earlier period. Notably, only in 2012 and 2014 did annual FFEs once again surpass 2000 events, a phenomenon likely attributable to the prolonged and severe drought experienced in Yunnan between 2012 and 201439,40, which led to a high average annual FFEs count of 2317—more than twice the average of other years, which stood at approximately 1000 events. During the period from 2015 to 2021, FFEs in the province stabilized, with an annual average of 1044 events.

Furthermore, statistical analyses reveal that years with high FFEs incidence (exceeding 2000 events) tend to correspond with a higher proportion of CFFEs and a concomitant rise in IFFEs, while years with lower FFEs incidence are characterized by a diminished presence of both CFFEs and IFFEs.

Seasonal classification of annual FFEs incidence, based on the traditional four-season scheme, reveals marked seasonal disparities, Fig. 4b. Overall, the annual distribution of FFEs across seasons follows a descending order of spring, winter, summer, and autumn, accounting for 74.19%, 17.37%, 7.73%, and 0.72% of total events, respectively. These findings indicate that spring and winter have historically accounted for over 90% of the annual FFEs occurrence, whereas summer and autumn combined have contributed less than 10%, consistent with other studies41,42,43.

Monthly analysis

Between 2001 and 2010, monthly FFEs in Yunnan Province were predominantly concentrated in the first five months of each year, Fig. 5, collectively accounting for an average of 92.8% of annual incidents, with February to April alone contributing as much as 73.9%; notably, in 2004, 2005, 2007, 2009, and 2010, the number of FFEs recorded in February or March exceeded 1150, culminating in the peak monthly values of 1721 and 1160 cases in February and March of 2010, respectively. Correspondingly, the total incidents for these years reached elevated annual proportions: 2622 cases in 2004 (75.8%), 1609 in 2005 (49.4%), 1958 in 2007 (71.7%), 2,167 in 2009 (69.6%), and 2981 in 2010 (67.5%); in contrast, the average February–March share during other years was only 58.1%, highlighting the pronounced temporal imbalance in monthly fire occurrences, with disproportionately high concentrations in the early months of the year and significantly reduced activity thereafter.

Since 2010—widely regarded as a turning point in forest fire management across Yunnan—the monthly frequency of FFEs has exhibited a sustained decline; peak monthly incidents in subsequent years consistently fell below 800 cases, with only minor deviations (e.g., 805 cases in February 2014), and this downward trend became more pronounced between 2017 and 2021, during which all monthly peaks remained under 400. Specifically, February–March incidents during these five years comprised 440 cases in 2017 (57.5%), 523 in 2018 (61.0%), 482 in 2019 (37.3%), 421 in 2020 (47.7%), and 526 in 2021 (61.6%), all markedly lower than the peak-month proportions observed between 2001 and 2010. This shift suggests that although February and March remain the primary months for fire activity, the number of monthly incidents during this period has declined substantially, indicating a trend toward more evenly distributed FFEs occurrences across the first half of the year.

Solar term analysis

As a key agroforestry province in southern China, Yunnan exhibits a marked correlation between crop phenology and the occurrence of wildfires. The Twenty-Four Solar Terms, derived from both empirical observation and scientific validation, not only demarcate the four seasons based on the sun’s path along the ecliptic but also divide the year into 15-day intervals, each reflecting specific climatic transitions and phenological phenomena44. This traditional temporal framework offers a more practical and granular temporal window for examining the spatio-temporal characteristics of FFEs in Yunnan Province, Fig. 6.

According to the temporal variations in FFEs across solar terms, FFEs predominantly occurred between Major Cold and Beginning of Summer (January 5 to May 20). After the beginning of Summer, the number of FFEs per solar term sharply declined and stabilized at ~20 events until a sustained increase began after the beginning of Winter (November 7), eventually peaking before the following year’s Pure Brightness (April 5).

Using 2010 as the cutoff year for the number of forest fire incidents occurring between solar terms, the peak values of FFEs between solar terms in all years prior to 2010 reached 500 incidents, except for 2008. In 2004 and 2009, the peak values even exceeded 750 events, with the highest value recorded during the Rain Water solar term (February 19–March 5) in 2010 (1198 events). During this period, the annual seasonal peaks, secondary peaks, and third peaks exhibited a clustering relationship, with the peaks and secondary peaks being closely aligned. The total number of FFEs during these three peaks accounted for an average of 59.2% of the annual total, indicating that ~60% (1031.6 events) of forest fires occurred within a 45–60 day period (average 52.5 days) each year.

From 2011 to 2016, only two solar terms recorded over 500 FFEs—Waking of Insects in 2014 (504 events) and Major Cold in 2016 (510 events). During this period, the three peak solar terms accounted for an average of 55.7% of annual FFEs (~502.6 events), with peak clustering becoming less pronounced than in the 2003–2010 period. The temporal window during which these events occurred expanded to 45–90 days (average: 67.5 days), reflecting a ~50% decline in fire frequency and a 15-day extension in fire duration compared to the earlier period.

Between 2017 to 2021, the peak values of FFEs during the solar terms did not exceed 250 events. The clustering of the three peak types (peak, secondary peak, and third peak) was further dispersed, and the differences between the peaks decreased significantly compared to the previous period. This indicates that forest fire events during this period were no longer significantly concentrated in a few major winter-spring solar terms but extended toward spring-type solar terms. and shifted toward and increased in summer-type solar terms. This indicates that the forest fire prevention period in Yunnan Province needs to be extended accordingly. Fortunately, since the relevant authorities introduced forest fire prevention period management regulations in 2021, the high-risk period (March 1 to April 30) within the forest fire prevention period (December 1 to June 15 of the following year) has been extended to May 31.

Duration analysis

A total of 39,101 FFEs, including both CFFEs and IFFEs, were recorded in Yunnan Province between 2001 and 2021. Among these, 88.6% (34,643 events) were extinguished or burned out within 0.5 days (corresponding to the left axis in Fig. 7). An additional 7.4% (2903 events) persisted for 0.5 to 1 day, 1.3% (517 events) for 1–2 days, and 1.4% (551 events) for 2–3 days. Only 1.1% (492 events) lasted longer than 3 days, as shown in Fig. 7.

Short-duration FFEs have significantly shaped the temporal patterns of forest fire occurrences in Yunnan Province, with a distribution predominantly concentrated between January and May, in line with the province’s designated fire-prone season. However, distinct differences in FFEs duration were observed across subregions.

In northeastern Yunnan, the lowest FFEs frequency was recorded, with a monthly average of 4.2 events. Of all FFEs in this subregion, 94.3% (1006 events) were short in duration. Notably, 40% of the short-duration FFEs (430 events) and 24 long-duration FFEs occurred in February, with monthly averages of 20.4 and 1.1 events, respectively.

In central Yunnan, the monthly average number of FFEs was 16.55. From January to April, short-duration FFEs accounted for 82.8% (1973 events), averaging 493 events per month. However, the peak months for short- and long-duration FFEs did not align; long-duration FFEs peaked one month later than short-duration ones. While only 17 short-duration FFEs occurred in May, long-duration FFEs increased unexpectedly to 28 events, suggesting a delayed and abrupt escalation of long-duration fires specific to this subregion.

In northwestern Yunnan, the monthly average was 29.6 FFEs, with both short- and long-duration events highly concentrated between January and March, averaging 823.3 and 164 events per month, respectively. This pattern indicates an earlier onset and rapid escalation of fire activity, sustained through April.

In southeastern Yunnan, the monthly average reached 105.2 FFEs, with peak short- and long-duration activity occurring in February and March—averaging 355.1 and 49.2 events per month, respectively. Despite comprising only 16.5% of Yunnan’s land area, this subregion accounted for 38.7% of all FFEs, identifying it as the most severely affected region and a priority for fire management.

In southwestern Yunnan, FFEs occurred at a monthly average of 108.3. From January to May, short-duration FFEs exhibited an A-shaped distribution, while long-duration FFEs were relatively low in January (85 events), surged in February (408 events), and peaked in March (530 events).

In summary, FFEs in Yunnan Province were predominantly concentrated in the first half of the year, particularly during February and March. From June to October, all subregions experienced low FFEs frequencies, followed by a gradual rise in short-duration FFEs from November, accompanied by the emergence of long-duration events. Although FFEs frequency generally decreased with increasing duration, slight rebounds were observed in the 2–3 day and 4–5 day classes, increasing by 0.1% (391.6 events) and 0.2% (783.2 events), respectively, compared to the preceding duration categories. A pronounced surge in long-duration FFEs from January to February was particularly evident in southeastern and southwestern Yunnan.

Discussion

This paper presents a novel approach combining MODIS AF data, BA data, and land cover type data from Yunnan Province for the period 2001–2021. Through methods such as AFSs pixelization, spatial extraction, and spatio-temporal clustering, the study aims to retain as many authentic and usable AFSs as possible to describe the spatio-temporal dynamics of forest fires in Yunnan Province. The findings are as follows:

Temporal studies indicate that the occurrence of forest fires in various regions of the province has generally shown a fluctuating downward trend over the years, stabilizing since 2017. This significant trend is largely due to effective policy formulation, fire prevention measures enacted by relevant departments, and the joint efforts of community groups. Looking back at the historical occurrence of forest fires, extreme climate conditions (such as La Niña/El Niño phenomena and consecutive droughts) remain the most significant adverse factors disrupting the spatio-temporal characteristics of forest fires38. For instance, in 2010, 2012–2014, and 2018, significant changes in forest fire occurrence were observed in Yunnan Province, particularly with frequent and scattered forest fires in the southwestern region. Additionally, complex and varied geographical factors contribute to the frequency of forest fires. In the northwestern Yunnan region studied in this research, the interaction between the Hengduan Mountains and southwest warm and humid air currents leads to the formation of foehn winds in certain river valleys45,46, creating “climate islands” with tropical characteristics, which exacerbate the frequency of forest fires. Although the number of forest fires in Yunnan Province remained stable between 2017 and 2021, global warming and the increasing frequency of extreme weather events41,47,48 are escalating forest fire risks worldwide. For example, vegetation fires in the rapidly greening Pan-Arctic region are increasing11, and extreme heat is amplifying forest fire risks in parts of India42.

The temporal clustering of forest fires within the year is even more pronounced. During the fire prevention period, the high-incidence period for forest fires in January–February coincides with the window period for various social activities. Research shows that nearly 90% of forest fires are directly or indirectly caused by human activities. January and February, as one of the periods with the most significant population mobility in China, witness a concentration of social activities such as returning home for the New Year, fireworks, spring plowing and burning, open-fire rituals, and tourism. Under the combined influence of this active, relaxed social atmosphere and widespread traditional social activities, there is a logical explanation for the significant occurrence of forest fires during this period. During March to May, the triggers for forest fires become more complex43, influenced by a combination of multiple driving factors. The most obvious factors are water-related elements such as rainfall, air humidity, moisture content of dead/living combustible materials, and soil moisture49,50. These factors are crucial for reducing the frequency of fires, so we introduce the 24 solar terms as a more granular time window on the temporal scale, which more essentially describes the annual variation patterns of water quantity and form. The 24 solar terms are applicable to most of China and even Asia, but this study only preliminarily utilized the time window. Further research should incorporate water-related data to deepen the analysis. During the non-fire prevention period, forest fire occurrence in Yunnan Province remains at a low level, primarily due to the climate characteristics of concurrent rainfall and heat. However, we logically infer that the primary triggers for the prolonged spring and shifted summer forest fire seasons in the central Yunnan region are likely the intensification of human activities and the relaxation of forest fire prevention awareness. Specifically, the central Yunnan region has high population density, good road accessibility, rapid forest fire response, and efficient prevention and control measures, which maintain low forest fire occurrence rates during the fire prevention period. During the transition phase between the fire prevention period and the non-fire prevention period (May), the public, who have experienced months of strict forest fire restrictions, may exhibit fatigue and relaxation in fire prevention awareness, coupled with increased outdoor recreational activities during holidays, as well as the cumulative effects of environmental conditions (combustible materials, temperature, etc.) and the oscillating cycle of alternating dry and wet periods (3–5 years)49. These factors collectively contribute to the prolonged spring season of frequent forest fires in the central Yunnan region. However, this requires further verification through the incorporation of additional data and the application of scientific and rigorous methods.

Spatial domain research results indicate that FFEs estimated using KDE exhibit significant clustering characteristics. This is particularly pronounced in most of southeastern Yunnan and the Pu’er region in southwestern Yunnan, which may be related to the region’s fragile ecological environment and human activities. Studies indicate that human activities accounted for 93% of forest fires in the Pu’er region between 2003 and 2016, with 65% of fires caused by slash-and-burn practices51. The northeastern and southeastern parts of Yunnan, located on China’s most typical karst terrain, originated from the uplift of the Earth’s crust, exposing soluble rocks at the surface, which were then eroded by water over long periods, resulting in sparse soil distribution. This environment is relatively suitable for the growth of shrubs with low soil requirements, while inhibiting the growth of tall trees, leading to land scarcity, rapid accumulation of flammable materials, and, combined with the tropical climate of southeastern Yunnan, planned burning practices, and slash-and-burn agriculture, has contributed to frequent forest fires in the region. In contrast, in northeastern Yunnan, combustible materials are distributed in fragmented patterns. Additionally, the quasi-stationary ridge along the north–south direction obstructs the flow of warm, moist air from the Pacific Ocean, resulting in relatively abundant moisture and lower temperatures in some parts of northeastern Yunnan. This maintains a lower incidence of forest fires in the region.

The spatial resolution of AF data (MODIS MCD14ML) was improved through cross-validation with high-resolution remote sensing data (GABAM and CLCD), thereby enhancing the accuracy and availability of FFSs and increasing their potential research value. In fields such as remote sensing mapping, researchers strive to reduce classification errors and omission errors in generated remote sensing data to provide a more comprehensive and objective representation of the real world. AF data can exclude BA pixels caused by classification errors within forest pixels, providing accurate spatio-temporal records for interannual BA data. Conversely, high-spatial-resolution BA data can remove high-confidence but erroneous fire points (e.g., drifting fire plumes; see Fig. 11d), thereby overcoming the limitations of traditional methods that screen high-availability FFSs based on high-confidence criteria (confidence ≤80). This provides new effective references for studying fire characteristics in high-latitude, cloudy mountainous regions (e.g., small-scale/weak forest fires, fire spread rates, peak fire intensity, and fire risk zoning).

Furthermore, the Terra/Aqua MODIS sensors, which have been in service for over 20 years, are nearing the end of their operational lifespan and are set to be retired. The vast dataset they have produced has been the most commonly used data source for previous studies on wildfire spatio-temporal dynamics. Subsequent studies often utilize the AF product suite (VIIRS V1/J1/J2)34 from the Trident satellites, which are the successors to MODIS. However, these two types of AF products exhibit significant differences in key parameters such as fire spot confidence, spatio-temporal resolution, and FRP. Therefore, introducing high-spatial-resolution third-party remote sensing data (such as the BA data used in this study) can serve as a reference for integrating the two AF spot datasets, thereby mitigating data mismatch issues caused by differences in confidence standards. This approach is applicable to studies requiring longer spatio-temporal spans and finer spatio-temporal scales.

Future research can combine remote sensing data with higher spatio-temporal resolution (such as NOAA/VIIRS, FY series, and geostationary satellites) to explore new factors influencing forest fires and assess their broader ecological impacts, such as estimating carbon flux emissions from forest fires and their feedback effects on atmospheric composition. Establishing a comprehensive forest fire information database and implementing it at regional and global scales can serve as a unified standard for detailed forest fire observation records, thereby better supporting forest fire research. Advanced geospatial technologies should be adopted and combined with current artificial intelligence technologies to enhance the reliability of forest fire risk zoning and prediction.

Methods

Study area

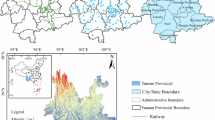

The study area is Yunnan Province (21°09′–29°15′N, 97°30′–106°12′E), located in the southwestern frontier of China. It spans a total area of 394,100 km2, with plateaus and mountains occupying over 90% of its territory, and a forest coverage rate reaching 60%. The terrain descends in a stepped pattern from the northwest (Meili Snow Mountain, elevation: 6740 m) to the southeast (Honghe River Valley, elevation: 76.4 m), with an average elevation of ~2000 m, This topography forms a typical highland mountainous landscape, Fig. 8a. The region encompasses four climatic zones—tropical, subtropical, temperate, and cold—and 26 ethnic minorities of China live in this generation.

a Distribution of MODIS Active Fire Spots (FFSs) within the study area in 2020 (Type = 0, confidence ≥ 0%). b Land cover types, geographical features, and administrative divisions of Yunnan Province in 2020 based on the CLCD with a spatial resolution of 30 meters (Northeast Yunnan includes: Zhaotong, Qujing; Southeast Yunnan includes: Wenshan, Honghe; Central Yunnan includes: Kunming, Yuxi, Chuxiong; Northwest Yunnan includes: Dali, Lijiang, Nujiang, Diqing; Southwest Yunnan includes: Pu’er, Xishuangbanna, Dehong, Baoshan, Lincang).

Based on natural geographical features, Yunnan is broadly divided into five major subregions, as shown in Fig. 8b: Northeast Yunnan is dominated by fragmented highland terrain with sparse vegetation; Southeast Yunnan exhibits typical karst landscapes with ecologically fragile environments; Central Yunnan enjoys a mild climate and is the province’s population and economic center; Northwest Yunnan comprises alpine gorges dominated by cold-temperate coniferous forests; and Southwest Yunnan features mountainous river valleys with well-developed tropical rainforests. The region’s complex geomorphology and distinctive climate conditions lead to uneven spatial climate distribution, giving rise to localized microclimates. These environmental characteristics have made Yunnan one of the most biologically rich areas on Earth, ranking among the top 25 global biodiversity hotspots52. A highly enriched gene pool of flora and fauna, together with the province’s diverse geo-climatic context and the continued practice of slash-and-burn agriculture, has made Yunnan one of the most wildfire-prone regions53.

Data sources

AF data

Compared to AF data collected by relevant authorities (which often face challenges such as limited human and material resources, leading to difficulties in data acquisition and incompleteness), the MODIS MCD14ML AF product, provided free of charge by FIRMS, offers a longer temporal span and moderate spatio-temporal resolution. It has been widely validated in wildfire studies at both regional and global scales28,29,54. The data are currently stored in a Standard Processing (SP) Level 2 vector format, including geographic coordinates of AFSs and related attribute information, as shown in Table 1. Each piece of data represents one or more heat sources/fires that may exist within the actual spatial resolution of MODIS, and under ideal observation conditions, even small-scale fires as small as 100 m2 or 50 m2 can be detected24, providing long-term and standardized data support for global forest fire spatio-temporal characteristic studies.

BA data

The Global Annual Burned Area Maps (GABAM) is an automated dataset of BA data generated using nearly all available Landsat imagery on the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform. It provides free access to 30-meter annual BA data for most regions of the world from 2000 to 2021 (covering the range 180°W–180°E and 80°N–60°S), with detailed information available in Table 2. This dataset demonstrates a similar spatial distribution and strong correlation when compared with the BA in the Fire_CCI 5.0 product. In global stratified sampling validation, the commission errors and omission errors of GABAM were 13.17% and 30.13%, respectively, with global accuracy exceeding 90%26.

Land Cover Dataset

The China Land Cover Dataset (CLCD) is a dataset used to describe Cand Cover Types and their spatial distribution in China from 1985 to 2023. It is also jointly developed and regularly updated based on the GEE platform55, with high temporal and spatial consistency56. It includes nine major land cover types: Cropland, Forest, Shrub, Grassland, Water, Snow/Ice, Barren, Impervious, and Wetland, as shown in Fig. 8b and Table 2.

Data processing methods

To match the spatio-temporal characteristics of multi-source remote sensing data and to investigate the spatio-temporal dynamics of FFEs, a series of datasets—AFSs, BA, and Land Cover Type—from Yunnan Province during 2001–2021 were processed using ArcGIS Pro and Python. The method flowchart is shown in Fig. 9.

First, to preserve potential wildfire information to the greatest extent, all suspected vegetation fire spots (i.e., TYPE = 0; total of 133,968) were retained, encompassing the full range of confidence levels (0 %≤ confidence ≤100%). AFSs located within forest, shrubland, and grassland pixels in the Land Cover Type dataset were uniformly classified as FFSs, while Active Fire Spots(AFSs) associated with cropland, urban, and other non-target land types were excluded.

Second, to improve the spatial accuracy of FFSs, the actual spatial extent of each point was reconstructed based on the orbital characteristics of the EOS MODIS sensor and metadata fields (TRACK and SCAN) in the MCD14ML product. The observation geometry under which surface thermal anomalies were detected by MODIS was restored to ensure accurate matching with corresponding BA pixels in subsequent analysis, as shown in Fig. 10.

a Schematic illustration of the inclination angle between the Aqua satellite’s orbit and the equatorial plane, used to determine the angle of the pixelated active fire spots of the satellite source. b Schematic illustration of the inclination angle between the Terra satellite’s orbit and the equatorial plane, used to determine the angle of the pixelated active fire spots of the satellite source. c Pixelized forest active fire spots.

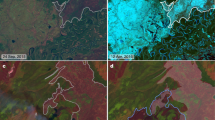

Secondly, to retain as many genuine AFSs as possible, the following situations must be distinguished during the overlay screening of AF and BA data: First, reduce the misclassification error caused by BA data incorrectly identifying farmland or bare soil pixels as BA, and exclude unnecessary BA pixels such as urban fires (Fig. 11a), and ignore the interference of BA pixels that are still misclassified within forest pixels (Fig. 11b). Second, for AF spots where there are no BA pixels within their pixelization range (Fig. 11c), we believe that this is likely due to misclassification errors in the BA data or temporary heat sources detected by MODIS during its pass that did not result in forest fires, and therefore, we also exclude such active FFSs. Third, in a given forest fire, the pixel-based forest AF spots exhibit significant spatial displacement, and the larger the fire area, the farther these fire spots deviate from the BA pixels. Some fire spots have displacement distances exceeding the pixelization range (Fig. 11d). Therefore, this process retains only forest AF spots that still overlap with BA pixels after pixelization, focusing on actual forest fires. In summary, after cross-validation among various datasets, 71,263 FFSs (accounting for 53.29% of the total) were selected from the initial 133,968 AFSs.

a Comparison of before and after removal of misclassified farmland/bare soil from BA pixels. b The contiguous black pixels on the left side of the image show BA pixels that was misclassified within the forest area. c Yellow dots indicate invalid forest fire spots within the forest area. d Yellow dots indicate active fire spots that were misclassified due to being too far from BA pixels.

Finally, in order to cluster spatially and temporally discrete FFSs into FFEs31, this study adopts a machine learning-based spatio-temporal clustering algorithm, ST-DBSCAN. This method segments spatio-temporal entities into a series of distinct clusters based on similarity criteria, thereby addressing the integration of spatial, non-spatial, and temporal attributes of AFSs57. Three key threshold parameters were determined by synthesizing multi-year official forest fire reports from Yunnan Province, prior research31, and empirical estimates derived from visual inspection: spatial threshold (Eps) = 2000 m, temporal threshold (Δt) = 6 days, and density threshold (MinPts) = 2.

To ensure that all available AFSs are incorporated into fire event clusters, a minimum density threshold of MinPts = 2 was applied. This yielded two categories of FFEs: Clustered FFEs (CFFEs, MinPts ≥ 2) and Isolated FFEs (IFFEs, MinPts = 1). Each CFFEs and IFFEs was assigned a unique event identifier. Furthermore, to satisfy the requirements of spatio-temporal clustering and subsequent analysis, each forest fire point was converted from UTC to Beijing Time, and the Day-Of-Year (DOY) was computed cumulatively.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors.

Code availability

The code for this study is available upon reasonable request from the authors.

References

Cunningham, C. X. et al. Increasing frequency and intensity of the most extreme wildfires on Earth. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 1420–1425 (2024).

Revich, B. A. Climate change and forest fires as health risk factors (analytical review). Health Risk Anal. 3, 132–145(2024).

Flannigan, M. D. et al. Climate change and forest fires. Sci. Total Environ. 262, 221–229 (2000).

Ciais, P. et al. The carbon balance of Africa: synthesis of recent research studies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 369, 2038–2057 (2011).

Forradellas, A. C. Ecology, meteorology and simulation of large wildland fires. Available at: https://repositori.udl.cat/items/8bfca74a-12b4-4716-8faf-8621963921f8/full (2015).

Diakakis, M. et al. Analysis of forest fire fatalities in Greece: 1977–2013. Int. J. Wildland Fire 25, 797–809 (2016).

Stevens-Rumann, C. S. et al. Evidence for declining forest resilience to wildfires under climate change. Ecol. Lett. 21, 243–252 (2018).

Cardil, A. et al. Extreme temperature conditions and wildland fires in Spain. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 122, 219–228 (2015).

Taylor, A. H. et al. Socioecological transitions trigger fire regime shifts and modulate fire–climate interactions in the Sierra Nevada, USA, 1600–2015 CE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 13684–13689 (2016).

Westerling, A. L. et al. Warming and earlier spring increase western U.S. forest wildfire activity. Science 313, 940–943 (2006).

Li, Y. et al. Trends and drivers of Arctic-boreal fire intensity between 2003 and 2022. Sci. Total Environ. 926, 172020 (2024).

Jolly, W. M. et al. Climate-induced variations in global wildfire danger from 1979 to 2013. Nat. Commun. 6, 7537 (2015).

Bowman, D. M. et al. Fire in the earth system. Science 324, 481–484 (2009).

Archibald, S. et al. Evolution of human-driven fire regimes in Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 847–852 (2011).

Westerling, A. L. et al. Warming and earlier spring increase western US forest wildfire activity. Science 313, 940–943 (2006).

Parente, J. et al. Space-time clustering analysis of wildfires: the influence of dataset characteristics, fire prevention policy decisions, weather and climate. Sci. Total Environ. 559, 151–165 (2016).

Lian, C. et al. Accelerating decline of wildfires in China in the 21st century. Front. Glob. Change 6, 1252587 (2024).

Wang, W. et al. Seasonal differences in the spatial patterns of wildfire drivers and susceptibility in the southwest mountains of China. Sci. Total Environ. 869, 161782 (2023).

Van Der Werf, G. R. et al. Carbon emissions from fires in tropical and subtropical ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 9, 547–562 (2003).

Randerson, J. T. et al. The impact of boreal forest fire on climate warming. Science 314, 1130–1132 (2006).

Hohner, A. K. et al. Wildfires alter forest watersheds and threaten drinking water quality. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 1234–1244 (2019).

Voulgarakis, A. & Field, R. D. Fire influences on atmospheric composition, air quality and climate. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 1, 70–81 (2015).

Alcañiz, M. et al. Effects of prescribed fires on soil properties: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 613, 944–957 (2018).

Giglio, L. et al. The collection 6 MODIS active fire detection algorithm and fire products. Remote Sens. Environ. 178, 31–41 (2016).

Zhou, M. et al. Enhancement of nighttime fire detection and combustion efficiency characterization using Suomi-NPP and NOAA-20 VIIRS instruments. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 1–20 (2023).

Long, T. et al. 30 m resolution global annual burned area mapping based on Landsat images and google earth engine. Remote Sens. 11, 489 (2019).

Katagis, T. & Gitas, I. Z. Assessing the accuracy of MODIS MCD64A1 C6 and FireCCI51 burned area products in Mediterranean ecosystems. Remote Sens. 14, 602 (2022).

Fornacca, D. et al. Performance of three MODIS fire products (MCD45A1, MCD64A1, MCD14ML), and ESA Fire_CCI in a mountainous area of Northwest Yunnan, China, characterized by frequent small fires. Remote Sens. 9, 1131 (2017).

Fu, Y. et al. Fire detection and fire radiative power in forests and low-biomass lands in Northeast Asia: MODIS versus VIIRS fire products. Remote Sens. 12, 2870 (2020).

FIRMS, N. Fire information for resource management system. Available at: https://firms.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/ (2022).

Dong, B. et al. Spatiotemporal analysis of forest fires in China from 2012 to 2021 based on visible infrared imaging radiometer suite (VIIRS) active fires. Sustainability 15, 9532 (2023).

Randerson, J. et al. Global burned area and biomass burning emissions from small fires. J. Geophys. Res, Biogeosci. 117, Issue G4 (2012).

Justice, C. et al. The MODIS fire products. Remote Sens. Environ. 83, 244–262 (2002).

Schroeder, W. et al. The New VIIRS 375 m active fire detection data product: algorithm description and initial assessment. Remote Sens. Environ. 143, 85–96 (2014).

Li, B. et al. Development of a finer-resolution multi-year emission inventory for open biomass burning in Heilongjiang Province. China Sci. Rep. 14, 1–12 (2024).

Xu, H. et al. Temporal–spatial characteristics and influencing factors of forest fires in the tropic of cancer (Yunnan Section). Forests 15, 661 (2024).

Zong, X. et al. Occurrence and hotspots of multivariate and temporally compounding events in China from 1961 to 2020. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 1–11 (2023).

Yin, J. et al. Drought-related wildfire accounts for one-third of the forest wildfires in subtropical China. Agric. Meteorol. 346, 109893 (2024).

Abbas, S. et al. Characterization of drought development through remote sensing: a case study in Central Yunnan, China. Remote Sens. 6, 4998–5018 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. Drought variability at various timescales over Yunnan Province, China: 1961–2015. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 138, 743–757 (2019).

Zhao, R. et al. Projections of compound wet-warm and dry-warm extreme events in summer over China. J. Hydrol. 639, 131635 (2024).

Sahu, V. et al. Assessing forest fire dynamics and risk zones in Central Indian forests: a comparative study of the Khandwa and North Betul forest divisions of Madhya Pradesh. Environ. Monit. Assess. 196, 810 (2024).

Zhu, Z. et al. How environmental factors affect forest fire occurrence in yunnan forest region. Forests 13, 1392 (2022).

Yang, J. et al. Global 24 solar terms phenological MODIS normalized difference vegetation index dataset in 2001–2022. Geosci. Data J. 11, 936–947 (2024).

Zumbrunnen, T. et al. Linking forest fire regimes and climate—a historical analysis in a dry inner alpine valley. Ecosystems 12, 73–86 (2009).

Fan, Z.-X. & Thomas, A. Spatiotemporal variability of reference evapotranspiration and its contributing climatic factors in Yunnan Province, SW China, 1961–2004. Clim. Change 116, 309–325 (2013).

Wang, L. & Ma, S. Extreme winter-spring drought in Southwest China in 2023: response to the phase transition from La Niña to El Niño. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 084042 (2024).

Jain, P. et al. Observed increases in extreme fire weather driven by atmospheric humidity and temperature. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 63–70 (2022).

Yang, C. et al. Spatial and temporal evolution characteristics of drought in Yunnan Province from 1969 to 2018 based on SPI/SPEI. Water Air Soil Pollut. 230, 1–13 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. Spatial and temporal patterns and driving factors of forest fires based on an optimal parameter-based geographic detector in the Panxi region, Southwest China. Fire Ecol. 20, 27 (2024).

Fujing, Z. Study on forest fire occurrence law and forest fire risk grade in pu’er city, yunnan province. Beijing Forestry University. (2018).

Yang, Y. et al. Biodiversity and biodiversity conservation in Yunnan, China. Biodivers. Conserv. 13, 813–826 (2004).

Ying, L. et al. Relative humidity and agricultural activities dominate wildfire ignitions in Yunnan, Southwest China: Patterns, thresholds, and implications. Agric. Meteorol. 307, 108540 (2021).

Roy, D. P. et al. The collection 5 MODIS burned area product—global evaluation by comparison with the MODIS active fire product. Remote Sens. Environ. 112, 3690–3707 (2008).

YangJie, H. X. The 30 m annual land cover dataset and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 3907–3925 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Regional accuracy assessment of 30-meter GLC_FCS30, GlobeLand30, and CLCD products: a case study in Xinjiang area. Remote Sens. 16, 82 (2023).

Birant, D. & Kut, A. ST-DBSCAN: an algorithm for clustering spatial–temporal data. Data Knowl. Eng. 60, 208–221 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects, China (Grant No. 202301AT070223); the Yunnan Reserve Projects for Young and Middle-Aged Academic and Technological Leading Talent (Grant No. 202405AC350034); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32160374).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.D., F.Z. ; Methodology, H.D., F.Z.; Software, H.D., J.Z. and D.L.; Validation, H.D., J.Z., and F.Z.; Data curation, S.C., J.Z. and D.L.; Writing – original draft preparation, H.D. and F.Z.; Writing –review and editing, H.D. and F.Z.; Visualization, H.D.; Supervision, F.Z.; Project administration, F.Z.; Funding acquisition, F.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, H., Li, D., Cai, S. et al. Spatio-temporal dynamics of forest fire occurrence in Yunnan, China from 2001 to 2021 based on MODIS. npj Nat. Hazards 2, 52 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00102-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00102-6