Abstract

Precipitation plays a crucial role in landslides, which most studies have disregarded the impact of compound temporal precipitation. Here, we developed models that incorporate compound temporal precipitation, constructed by jointly characterizing long-term accumulated precipitation and short-term precipitation immediately preceding landslides. Results show that integrating compound temporal precipitation improves predictive accuracy, with AUC increases of 1.0–6.9% across different experimental settings. The influence of compound temporal precipitation exhibits clear spatial and seasonal heterogeneity. Southern China is more sensitive to compound temporal precipitation, especially in the southeastern coastal region. The effect intensifies during summer and autumn when precipitation seasonality is strongest. Overall, this study demonstrates that integrating compound temporal precipitation not only boosts predictive accuracy but also provides new insights into the spatiotemporal variability of landslide susceptibility. These findings underscore the necessity of incorporating compound temporal precipitation in future frameworks for landslide prediction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Landslides are one of the most destructive natural disasters in the world1,2,3, characterized by abrupt initiation and extensive spatial coverage4,5. They often cause significant casualties, property losses, and damage to critical infrastructure such as transportation, telecommunication, and energy systems6,7,8,9. In addition, climate change has intensified both the frequency and magnitude of precipitation events by altering weather patterns, leading to increased surface runoff10. Since precipitation is one of the primary triggers of landslides11,12, understanding how precipitation characteristics drive landslide occurrence is essential for improving predictive accuracy and disaster preparedness.

Previous studies have primarily concentrated on the relationship between precipitation and landslides using physically based models13,14,15,16,17,18,19. These models quantify the influence of precipitation on landslide initiation by defining precipitation thresholds and integrating physical parameters to simulate hydrological and geotechnical processes20. A variety of physically based models have been developed for landslide susceptibility assessment. These models can be broadly classified into precipitation threshold–based approaches and slope stability–based models. The latter are more widely applied and include grid-based transient infiltration models, finite element methods, and infinite slope models21,22,23. However, these physically based models generally require precipitation to be prescribed at fixed temporal resolutions, which constrains their ability to systematically capture the compound temporal characteristics of precipitation, particularly the interaction between long-term accumulation and short-term intensification. Moreover, these physically based models are generally limited to small scale studies due to their dependence on detailed geotechnical and hydrological parameters, which are difficult to obtain for large region24,25,26. However, landslide early warning requires analyses at large spatial scales, for which data-driven approaches are particularly suitable. Data-driven methods have been increasingly adopted in landslide susceptibility assessment and have demonstrated substantial advantage27. Among these, machine learning28,29 and deep learning30 have gained substantial attention in recent years. These algorithms can effectively capture complex, nonlinear relationships between environmental covariates and historical landslides, enabling large-scale applications31,32. Commonly applied algorithms in landslide susceptibility assessment include Random Forest (RF)33,34, Support Vector Machine (SVM)35,36,37, Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)38,39, and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)40,41.

However, most data-driven models for landslide prediction still rely on a single precipitation covariate42,43,44. Such simplification overlooks this limitation, recent studies45,46 have begun incorporating multiple precipitation covariates to better represent these processes, which are jointly controlled by precipitation duration cumulative precipitation, and precipitation intensity. By analyzing metrics such as consecutive precipitation days and precipitation intensity, these approaches enable a more accurate characterization of the hydrological processes that lead to landslides. While previous studies have explored the influence of precipitation on landslides, they predominantly treat each precipitation variable separately and have yet to fully appreciate the significance of compound temporal precipitation in landslides. Compound temporal precipitation refers to the combined effects of long-term antecedent precipitation and short-term precipitation events. In this structure, antecedent precipitation governs the progressive build-up of soil moisture, while a subsequent short and intense precipitation episode provides the immediate triggering force for landslide initiation. This structure captures the interaction between long-duration antecedent precipitation, which controls hydrological preconditioning47, and short-term extreme precipitation, which governs the immediate triggering48. In contrast, traditional precipitation covariates (e.g., cumulative precipitation, precipitation intensity, or consecutive wet days) describe single aspects of precipitation but do not represent the temporal compounding effect across multiple temporal windows. Therefore, while multivariable precipitation studies have advanced landslide modelling. They do not fully capture the compound temporal structure arising from the interplay between long-term moisture accumulation and short-term precipitation extremes. This interaction is essential for understanding and predicting landslide occurrence.

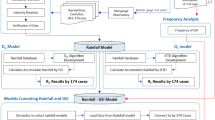

Given these challenges, we developed the dynamic landslide prediction models using a data-driven methods, incorporating compound precipitation across different temporal scales. To identify the most suitable modeling algorithm among data-driven approaches, we evaluated the performance of several machine learning methods and ultimately adopted Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) to build the dynamic landslide susceptibility assessment models. The importance of covariates was evaluated using Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) analysis, and dependence assessments were performed to examine the effects of compound temporal precipitation. The spatiotemporal influence of compound temporal precipitation in China during 2014 was analyzed. Figure 1 illustrates the framework of the landslide susceptibility assessment model based on compound temporal precipitation proposed in this study.

The analysis considered static covariates including elevation, slope, soil moisture (SM), land use and land cover change (LUCC), lithology, and annual precipitation (PreYearly). Compound temporal precipitation was incorporated by combining cumulative precipitation over the month preceding landslide occurrence (PreMonthly) with precipitation on the day of occurrence (Pre0) and cumulative precipitation over the previous 3, 5, and 7 days (PreSum3, PreSum5, PreSum7) to construct four models (LGBM-MD, LGBM-MT, LGBM-MF, LGBM-MS). Model performance was evaluated using random, spatial, and temporal cross-validation (RCV, SCV, TCV) with receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and area under the curve (AUC) as metrics, and feature contributions were analyzed using SHAP.

Results

Model selection

In this study, Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) analysis was performed conducted on the static covariates. In Fig. 2, the correlation coefficients between any two static covariates did not exceed 0.749. Therefore, elevation, slope, soil moisture (SM), land use and land cover change (LUCC), lithology, and annual precipitation (PreYearly) were retained for subsequent model construction, with no covariates removed.

The models selected for this study included LightGBM, RF, SVM, and XGBoost. All static covariates were treated as explanatory covariates for evaluating model performance. The covariates were used to fit each model and compare their predictive capabilities. In Fig. 3, RF and LightGBM achieved the highest area under the curve (AUC) values of 0.979 and 0.975, respectively, demonstrating superior predictive accuracy compared with SVM and XGBoost. LightGBM shows a marginal improvement in precision (88.7%) over RF (88.4%). Considering both predictive accuracy and computational efficiency, particularly when handling large scale datasets, LightGBM demonstrated faster processing speeds. Accordingly, LightGBM was used to construct the dynamic landslide susceptibility assessment models incorporating compound temporal precipitation.

Enhancement of model performance considering compound temporal precipitation

We developed landslide susceptibility models based on LightGBM and incorporating compound temporal precipitation. Four models were constructed using cumulative precipitation over the month preceding landslide occurrence combined with short-term precipitation over different temporal windows. The first model combined precipitation on the event day (Pre0) with the previous month’s cumulative precipitation (LGBM-MD). To assess the influence of short-term antecedent precipitation, a second model incorporating three-day antecedent precipitation (PreSum3) and the previous month’s cumulative precipitation was constructed (LGBM-MT). Extending this approach, a third model incorporating five-day antecedent precipitation (PreSum5) and the previous month’s cumulative precipitation was constructed (LGBM-MF). Finally, a model combining seven-day antecedent precipitation (PreSum7) with the previous month’s cumulative precipitation was developed (LGBM-MS). For comparison, models without dynamic precipitation covariates (LGBM) and with only the previous month’s cumulative precipitation alongside static covariates (LGBM-M) were also considered. To comprehensively evaluate predictive performance, we employed ten-fold random cross-validation (RCV), spatial cross-validation (SCV), and temporal cross-validation (TCV) to comprehensively evaluate the predictive performance of models incorporating compound temporal precipitation (Table 1).

When only static covariates were considered, without dynamic precipitation covariates preceding landslides, the mean AUC under RCV was 0.976. Including the cumulative precipitation in the month preceding landslides led to a slight improvement in mean AUC. When compound temporal precipitation before landslides was incorporated, the mean AUC further increased across different combinations of temporal precipitation. The highest mean AUC of 0.986 was achieved when combining the cumulative precipitation of the month preceding the landslide with precipitation on the day of the landslide occurrence. This demonstrated the effectiveness of compound temporal precipitation in enhancing predictive accuracy. For SCV, the model based solely on static covariates yielded a mean AUC of 0.855. Adding the cumulative precipitation of the month preceding landslides increased the AUC to 0.873, and incorporating compound temporal precipitation covariates further improved predictive performance. Similarly, under TCV, the model with only static covariates achieved a mean AUC of 0.877, which rose to 0.882 when the previous monthly cumulative precipitation was added. Incorporation of compound temporal precipitation further improved performance, with the model including precipitation on the day of landslide occurrence reaching the highest mean AUC of 0.892.

Incorporating compound temporal precipitation improved model performance across all cross-validation strategies, but the magnitude of improvement varied. In RCV, the mean AUC increased by approximately 1.0%, indicating a modest improvement. Under TCV, mean AUC rose by about 1.7%, suggesting a slight enhancement in temporal generalization. In contrast, SCV showed a mean AUC improvement of approximately 6.9%, substantially higher than RCV and TCV. These results indicate that while compound temporal precipitation only slightly enhances temporal generalization, it plays a more critical role in spatial generalization. This is because it captures both long-term wetting and short-term intense precipitation patterns that vary across different regions.

Additionally, the predictive performance of the models was further evaluated using confusion matrix analysis. Across all compound temporal precipitation models for dynamic landslide susceptibility assessment (Fig. 4), the overall classification accuracy exceeded 90%. Compared with the model that did not incorporate compound temporal precipitation covariates, the proposed models exhibited notably higher classification accuracy. Among them, compound precipitation on the day of landslide occurrence achieved the best classification performance, with true positives (TP) accounting for 31.5%, true negatives (TN) for 62.9%. False positives (FP) and false negatives (FN) accounted for only a small proportion of the total predictions. These findings further show the strong predictive capability of the proposed models, with the model incorporating precipitation data from the landslide day exhibiting the most effective performance. The stronger effect under certain spatial contexts also implies that geological and topographical conditions may modulate the sensitivity of landslide occurrence to these precipitation patterns. These observations provide a natural rationale for further investigation through SHAP analysis, which can elucidate the relative importance of different temporal precipitation features and their interactions with static covariates in driving landslide susceptibility predictions.

Interpretation of the model incorporating compound temporal precipitation

The results provide initial evidence that explicitly accounting for compound temporal precipitation enhances the accuracy of landslide prediction. Moreover, SHAP analysis enables a deeper understanding of the driving role of compound temporal precipitation in the models and improves model interpretability. Across all compound temporal precipitation models, annual precipitation remained the strongest influence on model predictions (Fig. 5), consistently exhibiting the highest SHAP values. Short-term precipitation preceding landslide events exerted a stronger promoting effect than the cumulative precipitation of the month preceding landslide occurrence. The SHAP dependence plots reveal a clear threshold-dependent relationship between cumulative precipitation and model predictions. At low precipitation levels, precipitation contributes weakly or negatively to landslide susceptibility, suggesting that insufficient precipitation alone is unlikely to trigger landslides. Once cumulative precipitation exceeds a certain threshold, it consistently contributes positively, indicating a pronounced nonlinear response.

a, d, g, j Show feature importance for LGBM-MD, LGBM-MT, LGBM-MF, and LGBM-MS, respectively. b, e, h, k Depict feature dependence plots for precipitation on the event day and the three-day, five-day, and seven-day antecedent periods for the corresponding models (LGBM-MD, LGBM-MT, LGBM-MF, and LGBM-MS). c, f, i, l Show feature dependence plots of monthly cumulative precipitation for the models.

The interactions among compound temporal precipitation covariates were evaluated using Partial Dependence Plots as shown in Fig. 6. The probability of landslide occurrence increases notably when high short-term precipitation coincides with high antecedent monthly accumulation. When daily precipitation on the landslide day reaches around 125 mm, the probability of landslides is substantially elevated, particularly if the one-month cumulative precipitation exceeds 200 mm. Even under low daily precipitation, landslide probability remains elevated if the monthly cumulative precipitation surpasses 400 mm. A similar pattern is observed for cumulative precipitation in the days preceding landslide events. Landslide probability is relatively high when the three-day precipitation prior to the landslide exceeds approximately 125 mm under one-month cumulative totals above 530 mm. The probability of landslide occurrence is relatively high when the five-day antecedent cumulative precipitation exceeds 210 mm and the cumulative precipitation over the preceding month is around 490 mm. In addition, the probability is relatively high when the seven days preceding the landslide reaches approximately 220 mm and monthly precipitation exceeds 300 mm. These results indicate that prolonged antecedent wetness primarily conditions slope stability, while short-term precipitation serves as the immediate trigger for landslide occurrence. High probability conditions consistently arise when heavy short-term precipitation coincides with elevated monthly precipitation, underscoring the critical role of compound temporal precipitation in landslides. It should be noted that the identified thresholds do not represent deterministic triggering limits, but rather reflect probabilistic transition zones where the model sensitivity to precipitation increases markedly.

Spatiotemporal characterization of compound temporal precipitation

In addition, this study examined the influence of compound temporal precipitation on landslide occurrence across temporal and spatial dimensions. For each sample, SHAP values were calculated for all features. The feature with the highest SHAP value was identified as the dominant one. The proportion of samples dominated by each feature was then computed to investigate the temporal and spatial distribution of compound temporal precipitation.

In the spatial dimension, the distribution of the effects of compound temporal precipitation was analyzed across nine major river basins in China (Fig. 7). These basins were selected as they encompass the main topographic and climatic zones of the country, providing a comprehensive representation of regional precipitation patterns and their influence on landslide occurrence. The results indicate that landslides in the Southeast River Basin (SERB) and the Yangtze River Basin (YZRB) are more strongly influenced by compound temporal precipitation of the one-month antecedent cumulative and the landslide day, and a strong response is also observed in the Pearl River Basin (PERB). In contrast, the Continental River Basin (CORB), Songhua and Liaohe River Basin (SLRB), and Haihe River Basin (HARB) exhibit relatively weak responses to compound temporal precipitation of the one-month antecedent cumulative and the landslide day. The influence of compound temporal precipitation of the one-month antecedent cumulative and the three-day antecedent precipitation is most pronounced in the SERB and the Yellow River Basin (YERB), followed by the Southwest Rivers Basin (SWRB), Huaihe River Basin (HURB), and PERB. However, in the YZRB, where landslides occur frequently, this temporal scale of precipitation shows a relatively weak effect. The CORB and HARB exhibit minimal influence from the compound temporal precipitation of the one-month antecedent cumulative and the three-day antecedent precipitation. The influence of compound temporal precipitation of the one-month antecedent cumulative and the five-day antecedent precipitation is most pronounced in the SERB, the SWRB and the YERB. Regarding compound temporal precipitation of the one-month antecedent cumulative and the seven-day antecedent precipitation, the strongest impacts occur in the SERB, the PERB, the SWRB and the YERB. The YZRB and SLRB in China are also influenced to some extent. In comparison, the CORB, HARB, and HURB show minimal effects. In conclusion, the results demonstrate that the influence of compound temporal precipitation across multiple temporal scales varies notably among basins. In the SERB, landslides are predominantly affected by compound temporal precipitation. In contrast, landslides in the YZRB are more sensitive to compound temporal precipitation of the one-month antecedent cumulative and the landslide day. Such contrasts underscore the strong regional variability in the effects of compound temporal precipitation on landslide occurrence.

a LGBM-MD, b LGBM-MT, c LGBM-MF, and d LGBM-MS. CORB denotes the Continental River Basin, SLRB denotes the Songhua–Liaohe River Basin, YERB denotes the Yellow River Basin, HARB denotes the Haihe River Basin, HURB denotes the Huaihe River Basin, SERB denotes the Southeast River Basin, YZRB denotes the Yangtze River Basin, SWRB denotes the Southwest River Basin, and PERB denotes the Pearl River Basin.

From a temporal perspective, compound temporal precipitation plays an important role in influencing landslides (Fig. 8). Specifically, the compound temporal precipitation of the one-month antecedent cumulative precipitation combined with precipitation on the landslide day shows a high contribution in September. In addition, for compound temporal precipitation in July, the one-month antecedent cumulative and landslide-day precipitation account for a larger share. Moreover, compared to cumulative precipitation over other periods, the one-month antecedent cumulative and landslide-day precipitation consistently contribute a higher percentage to the model predictions. The results indicate a relatively high influence of compound temporal precipitation in January. It should be noted that the percentages are calculated within each month, meaning that the model’s contribution of compound temporal precipitation is relatively high for landslide events occurring in January. However, the limited number of winter samples may affect representativeness, and future studies with larger winter datasets would yield more representative results. From a seasonal perspective, compound temporal precipitation exhibits varying impacts on landslides. The compound temporal precipitation of the one-month antecedent cumulative and landslide-day precipitation show stronger effects in spring, while in summer this combination contributes the largest share, followed by the compound temporal precipitation of the one-month antecedent cumulative and seven-day precipitation. During autumn, the compound temporal precipitation of the one-month antecedent cumulative and landslide-day precipitation has a significant effect, indicating its prominent role.

Discussion

In this study, our models incorporated compound temporal precipitation for landslides. This approach is innovative compared with previous studies50 because it captures both the long-term antecedent effects and the short-term triggering effects prior to landslide initiation. Monthly cumulative precipitation reflects the background wetness conditions of the slope and variations in groundwater levels, providing the hydrological setting for potential failures. In contrast, intense precipitation in the days immediately before the landslide and on the event day can rapidly increase water pressure within the soil, reduce shear strength, and directly trigger slope failure51. Cross-validation result (Table 1) show that incorporating compound temporal precipitation improved predictive performance. These findings indicate that compound temporal precipitation provides a more complete representation of hydrological mechanisms influencing landslides and enhances prediction accuracy. Although annual precipitation has the highest SHAP value, reflecting its importance in capturing the general hydrological background, its long temporal scale limits its ability to represent precipitation conditions immediately preceding landslide events. In contrast, compound temporal precipitation consistently shows higher feature importance than other covariates, highlighting its critical contribution to landslide susceptibility prediction. The partial dependence plot analysis (Fig. 6) further shows that when short-term cumulative precipitation is low, even a high level of cumulative precipitation in the previous month results in only a limited increase in model-predicted landslide probability. However, when short-term precipitation simultaneously increases substantially, landslides probability rises rapidly. This indicates a nonlinear superimposed relationship between short-term triggering effects and long-term accumulation effects. this study demonstrates that incorporating compound temporal precipitation significantly improves landslide susceptibility modeling.

This study further investigates the spatial and temporal differences in the effects of compound temporal precipitation. The results show that different river basins exhibit clear regional characteristics in their responses (Fig. 7). The YZRB is more sensitive to compound temporal precipitation of the one-month antecedent cumulative and landslide-day precipitation. While the CORB, the SLRB, and the HARB are relatively less affected by compound temporal precipitation. In contrast, the SERB are more strongly influenced. This suggests that the triggering mechanisms vary significantly across geomorphological and hydrological settings. From a temporal perspective, the seasonal characteristics of precipitation also influence landslide triggering mechanisms. During summer and autumn, when precipitation is concentrated and intense, the combined effects of short-term and long-term precipitation can easily induce landslides. Future research could further refine this approach by incorporating more comprehensive landslide datasets with larger sample sizes and improved temporal coverage. Nevertheless, the results of this study already provide initial evidence that explicitly accounting for compound temporal precipitation can enhance the accuracy of landslide prediction.

Methods

Study area and data overview

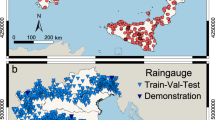

China is located in Eastern Asia, along the Western Pacific Ocean, with a national territory of approximately 9.6 million square kilometers. The convergence of diverse climate and complex topography makes landslides a frequent natural hazard throughout the region. For this study, we observed an inventory of 5372 landslide events across China in 2014 from the Ministry of Natural Resources of China. Spatially, most landslides were distributed in southern China (Fig. 9a), with the Yangtze River Basin recording the largest number of events (Fig. 9b). High concentrations of landslide events were recorded in Hunan Province, accounting for 35.9% of events, followed by Chongqing Municipality and Guizhou Province. Landslide events were unevenly distributed throughout the year (Fig. 9c), with a peak in the summer months corresponding to heavy precipitation. In total, summer accounted for 45.5% of the annual landslides and autumn for 32.8%. September saw the highest number of events, with 1662 landslides and followed by 1536 events in July. Negative samples were randomly selected to achieve a 2:1 ratio with positive landslide samples. After preprocessing, the resulting dataset contained a total of 15,933 samples.

Covariates

Drawing on previous research and expert judgment52,53,54, this study considers elevation, slope, soil moisture, lithology, land use and land cover change, and precipitation as the covariates (Table 2). These covariates capture terrain variability, geological setting, hydrological conditions, and human influence.

Elevation is one of the most widely used topographic covariates in landslide susceptibility assessments, providing an effective representation of terrain and exerting a significant influence on surface hydrological and geological processes. In this study, elevation was obtained from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) digital elevation model (DEM) with a spatial resolution of 90 m. Slope, another important terrain parameter, was derived from the DEM using the spatial analysis tools in ArcGIS. SM is an essential hydrological covariate, obtained from the European Space Agency (ESA) Soil Moisture Climate Change Initiative (CCI) project. The SM used in this study was daily observations across China for the entire year of 2014. To capture the effect of antecedent wetness on landslide occurrence, SM from the eighth day prior to each landslide event was selected. Lithology is a fundamental geological covariate in landslide susceptibility assessment. Distinct lithologic types exhibit pronounced differences in structural strength, permeability, and weathering properties, all of which govern slope stability and strongly influence landslide occurrence. Lithological data were obtained from the new global high resolution lithology map55. There are fifteen lithological categories in China, including Unconsolidated Sediments, Siliciclastic Sedimentary Rocks, Pyroclastic Rocks, among others. The LUCC obtained from the Resource and Environmental Science Data Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, influences landslide risk through its control on surface cover and vegetation, which are critical to slope stability. The classification system of the China Multi-period Land Use Remote Sensing Monitoring Dataset employs a two-tier framework. The first tier comprises six categories—arable land, forest land, grassland, water bodies, construction land, and unutilized land mainly based on land resources and their utilization attributes. The second tier is primarily based on the natural attributes of land resources and is further subdivided into 23 types. LUCC used in this study have a spatial resolution of 30 m.

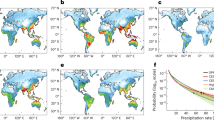

The precipitation dataset is a high-resolution meteorological dataset generated from daily observational data collected at over 2400 national meteorological stations across China (CN05.1)56,57,58. Precipitation at the national scale increases markedly from June to September. Spatially, areas of higher precipitation are predominantly distributed along the southeastern coastal regions. Based on previous studies59,60,61, precipitation accumulated over multiple antecedent periods, including one month, seven days, five days, three days, and the day of each landslide event, was extracted and used as dynamic covariates to evaluate the impact of compound temporal precipitation on landslide occurrence.

Feature selection

Correlations among explanatory covariates may induce multicollinearity and leading to redundancy. This can increase the variance of parameter estimates and reduce model interpretability62. To address these issues, correlation analysis was conducted prior to model construction. The PCC was applied to quantify linear associations among all covariate pairs, enabling the detection of highly correlated variables that may provide overlapping information. Covariates exhibiting excessively high correlation coefficients were reviewed and selectively removed to reduce redundancy while preserving the essential variability of environmental conditions represented in the dataset. This procedure ensures that the retained covariates remain relatively independent. It mitigates multicollinearity and improves the stability, interpretability and computational efficiency of subsequent landslide susceptibility models. The correlation coefficient can be broadly formulated as follows63:

Where X and Y represent two distinct covariates, \({X}_{i}\) and \({Y}_{i}\) denote their observed values, \(\bar{X}\) and \(\bar{Y}\) are the means of the respective covariates, and n denoting the sample size. The PCC measures the linear relationship between the covariates and ranges from -1 to 1. The strength of the correlation increases as the absolute value of the PCC approaches 1. In this study, a threshold of 0.7 is used to identify strongly correlated covariates. When the PCC between two covariates exceeds 0.7, one of the covariates is removed to avoid redundancy. However, no pair of static covariates exceeded this threshold in this study, and thus no covariates were removed.

LightGBM with compound temporal precipitation

In this study, we considered four machine learning models commonly applied in landslide susceptibility assessment, including RF, SVM, XGBoost, and LightGBM. A comparative evaluation revealed the superior predictive accuracy and computational efficiency of LightGBM, especially on large-scale datasets, leading to its selection as the core modeling framework. The model utilizes widely recognized static landslide-conditioning factors: elevation, slope, soil moisture, lithology, land use and cover change, and annual precipitation. The previous month’s cumulative precipitation was selected to characterize persistent wetness that gradually reduces soil strength and increases pore-water pressure, thereby creating favorable baseline conditions for slope failure. Shorter antecedent windows were incorporated to capture intense precipitation pulses that may directly initiate landslides once long-term saturation conditions have developed. To capture the role of precipitation as a triggering factor, cumulative precipitation values were calculated for multiple antecedent periods relative to each landslide event. Compound temporal precipitation refers to a combined indicator that considers both long-term and short-term cumulative precipitation prior to landslide occurrence, aiming to quantify the dynamic influence of precipitation on landslide susceptibility. Specifically, long-term precipitation in the compound temporal precipitation framework is defined as the cumulative precipitation during the one-month period prior to the landslide event, calculated as the accumulated precipitation over the 30 days preceding the event. Short-term precipitation is constructed using cumulative precipitation over multiple antecedent time windows, including seven days, five days, three days before the event, as well as the precipitation on the event day itself. It can be expressed as:

Where CTP is compound temporal precipitation, \({P}_{long}\) represents the cumulative precipitation over the month preceding the landslide occurrence:

and \({P}_{long}\) denotes the cumulative precipitation over a short-term window before the landslide:

Here, \({p}_{i}\) is the precipitation on day \(i\), \(t\) is the date of landslide occurrence, and \(n\) represents the length of the short-term window. When \(n=3\), it represents the three-day antecedent precipitation. When \(n=5\), it represents the five-day antecedent precipitation. When \(n=7\), it represents the seven-day antecedent precipitation. When \(i=t\), it represents the precipitation on the day of the landslide. For a landslide event occurring on 1 July 2014, the long-term precipitation corresponds to the cumulative precipitation from 1 June to 30 June 2014. The short-term precipitation components include the cumulative precipitation from 24 June to 30 June 2014 for the seven-day antecedent period, from 26 June to 30 June 2014 for the five-day period, from 28 June to 30 June 2014 for the three-day period, and the precipitation recorded on 1 July 2014 for the event-day component.

Based on these four different compound temporal precipitation covariates, four dynamic landslide susceptibility models incorporating compound temporal precipitation were constructed. LGBM-MD integrates the previous month’s accumulation with precipitation on the day of the landslide. LGBM-MT combines the previous month’s accumulation with precipitation over the three days prior to the landslide, while LGBM-MF considers the five days preceding the event. LGBM-MS incorporates precipitation accumulated over the previous month and the seven days preceding the event. This design allows systematic comparison across different temporal scales, providing a clearer understanding of how long-term and short-term precipitation jointly relate to landslide occurrence.

Validation of models incorporating compound precipitation

Model performance was evaluated using the ROC and AUC. The ROC is a widely used tool for assessing the classification capability of a model, where the True Positive Rate (TPR) is plotted against the False Positive Rate (FPR). The TPR reflects the ability of model to correctly identify positive instances, while the FPR represents the proportion of negative instances incorrectly classified as positive. A ROC that lies closer to the upper-left corner indicates better discrimination ability. The AUC ranges from 0 to 1 and is used to quantify the performance of a classifier. Values closer to 1 indicate stronger ability to distinguish between positive and negative classes. RCV involves randomly partitioning the dataset into k subsets. Each iteration selects one subset as the test set, while using the remaining subsets as the training set, performing k training and validation cycles. This study employs SCV, dividing the dataset into ten folds and conducting ten cross validation iterations. The mean AUC across these ten iterations is calculated and used as the predictive performance evaluation metric. Additionally, SCV was conducted to further validate the predictive accuracy of the models. The terrain of China is characterized by significant variations in elevation and complex topographic gradients across the country. Considering these substantial differences in terrain, this study implemented a SCV approach based on the concept of three major topographic steps of China. Based on elevation, the study area was divided into three regions for cross-validation. Specifically, areas with elevations below 500 meters were classified as one region. Elevations between 500 and 4000 meters formed a second region, and those above 4000 meters formed a third. After classification, the three regions were encoded, and each sample was assigned to its corresponding region. Two regions were used as the training set and the remaining one as the test set in each iteration. This process was repeated three times, and the mean AUC value across all iterations was calculated to evaluate the overall performance of the models. In addition, TCV as conducted to evaluate the model’s temporal robustness. A rolling window approach was adopted, where data from January were initially used for model training and applied to predict landslides in February. Subsequently, the training dataset was progressively expanded by including data from previous months to predict the following month, continuing until December. The mean AUC obtained from the twelve sequential prediction rounds was then calculated to provide an overall measure of model performance in the temporal domain.

The confusion matrix is an essential tool for evaluating the classification performance of a model, particularly in binary classification tasks. It provides a visual summary of the predictive outcomes by comparing predicted values with observed values. The matrix contains four key components, which are TP, TN, FP and FN. These components together describe the overall classification performance. In landslide susceptibility assessment, TP denotes samples where a landslide actually occurred and was correctly identified by the model. TN denotes samples where no landslide actually occurred and were correctly classified as non-landslides by the model. FP refers to samples where no landslide actually occurred but were incorrectly classified as landslides by the model. FN indicates samples where a landslide actually occurred but was incorrectly classified as non-landslide by the model. Analysis of the confusion matrix provides a comprehensive understanding of the model predictive performance across different categories, enabling a more accurate evaluation of its classification capabilities. Examining the confusion matrix allows a comprehensive evaluation of predictive performance for models across all categories, and provides a clear understanding of its classification capabilities.

Data availability

Elevation data were obtained from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission digital elevation model and are available at the following URL: https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov. Land-use and land-cover data were obtained from the Resource and Environmental Science Data Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and are available at the following URL: https://www.resdc.cn. Soil moisture data were obtained from the ESA Climate Change Initiative Soil Moisture product and are available at the following URL: https://researchdata.tuwien.at/records/8dda4-xne96. Lithological data were obtained from the Global Lithological Map Database and are available at the following URL: https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.788537. Precipitation data were obtained from the CN05.1 gridded daily precipitation dataset and are available at the following URL: https://ccrc.iap.ac.cn/index.php/resource/detail?id=228. The landslide inventory data generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to data licensing restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Di Napoli, M. et al. Rainfall-induced shallow landslide detachment, transit and runout susceptibility mapping by integrating machine learning techniques and GIS-based approaches. Water 13, 488 (2021).

Froude, M. J. & Petley, D. N. Global fatal landslide occurrence from 2004 to 2016. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 2161–2181 (2018).

Haque, U. et al. Fatal landslides in Europe. Landslides 13, 1545–1554 (2016).

Huang, F. et al. Modelling landslide susceptibility prediction: A review and construction of semi-supervised imbalanced theory. Earth-Sci. Rev. 250, 104700 (2024).

Keefer, D. K. Investigating landslides caused by earthquakes–a historical review. Surv. Geophys. 23, 473–510 (2002).

Martino, S. et al. Impact of landslides on transportation routes during the 2016–2017 Central Italy seismic sequence. Landslides 16, 1221–1241 (2019).

Bricheno, L. et al. The diversity, frequency and severity of natural hazard impacts on subsea telecommunications networks. Earth-Sci. Rev. 259, 104972 (2024).

Huang, C. et al. Study of direct and indirect risk assessment of landslide impacts on ultrahigh-voltage electricity transmission lines. Sci. Rep. 14, 25719 (2024).

Marchesini, I. et al. National-scale assessment of railways exposure to rapid flow-like landslides. Eng. Geol. 332, 107474 (2024).

Alcántara-Ayala, I. Landslides in a changing world. Landslides 22, 2851–2865 (2025).

Khan, S., Kirschbaum, D. & Stanley, T. Investigating the potential of a global precipitation forecast to inform landslide prediction. Weather Clim. Extremes 33, 100364 (2021).

Handwerger, A. L., Fielding, E. J., Sangha, S. S. & Bekaert, D. P. Landslide sensitivity and response to precipitation changes in wet and dry climates. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099499 (2022).

Gutierrez-Martin, A. A GIS-physically-based emergency methodology for predicting rainfall-induced shallow landslide zonation. Geomorphology 359, 107121 (2020).

Liu, H. D., Li, D. D., Wang, Z. F., Geng, Z. & Li, L. D. Physical modeling on failure mechanism of locked-segment landslides triggered by heavy precipitation. Landslides 17, 459–469 (2020).

Ma, S. Y., Shao, X. Y., Xu, C. & Xu, Y. R. Insight from a physical-based model for the triggering mechanism of loess landslides induced by the 2013 Tianshui heavy rainfall event. Water 15, 443 (2023).

Reder, A., Rianna, G. & Pagano, L. Physically based approaches incorporating evaporation for early warning predictions of rainfall-induced landslides. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 613–631 (2018).

Salvatici, T. et al. Application of a physically based model to forecast shallow landslides at a regional scale. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 1919–1935 (2018).

Wei, Z. L., Wang, D. F., Sun, H. Y. & Yan, X. Comparison of a physical model and phenomenological model to forecast groundwater levels in a rainfall-induced deep-seated landslide. J. Hydrol. 586, 124894 (2020).

Zhang, S. J., Zhao, L. Q., Delgado Tellez, R. & Bao, H. J. A physics-based probabilistic forecasting model for rainfall-induced shallow landslides at regional scale. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 969–982 (2018).

Segoni, S., Piciullo, L. & Gariano, S. L. A review of the recent literature on rainfall thresholds for landslide occurrence. Landslides 15, 1483–1501 (2018).

Montrasio, L., Schilirò, L. & Terrone, A. Physical and numerical modelling of shallow landslides. Landslides 13, 873–883 (2015).

Zhou, W. Q. et al. Combining rainfall-induced shallow landslides and subsequent debris flows for hazard chain prediction. Catena 213, 106199 (2022).

Ma, S., Shao, X., Xu, C., Chen, X. & Yuan, R. Topographic location and connectivity to channel of earthquake- and rainfall-induced landslides in Loess Plateau area. Sci. Rep. 15, 628 (2025).

Peruccacci, S., Brunetti, M. T., Luciani, S., Vennari, C. & Guzzetti, F. Lithological and seasonal control on rainfall thresholds for the possible initiation of landslides in central Italy. Geomorphology 139, 79–90 (2012).

Alvioli, M. & Baum, R. L. Parallelization of the TRIGRS model for rainfall-induced landslides using the message passing interface. Environ. Model. Softw. 81, 122–135 (2016).

Tran, T. V., Alvioli, M., Lee, G. & An, H. U. Three-dimensional, time-dependent modeling of rainfall-induced landslides over a digital landscape: a case study. Landslides 15, 1071–1084 (2018).

Zêzere, J., Pereira, S., Melo, R., Oliveira, S. & Garcia, R. A. Mapping landslide susceptibility using data-driven methods. Sci. Total Environ. 589, 250–267 (2017).

Ghorbanzadeh, O. et al. Evaluation of different machine learning methods and deep-learning convolutional neural networks for landslide detection. Remote Sens 11, 196 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Modelling of shallow landslides with machine learning algorithms. Geosci. Front. 12, 385–393 (2021).

Prakash, N., Manconi, A. & Loew, S. Mapping landslides on EO data: Performance of deep learning models vs. traditional machine learning models. Remote Sens 12, 346 (2020).

Gong, W., Zhang, S., Juang, C. H., Tang, H. & Pudasaini, S. P. Displacement prediction of landslides at slope-scale: Review of physics-based and data-driven approaches. Earth-Sci. Rev. 258, 104948 (2024).

Li, S., Wu, L., Chen, J. & Huang, R. Multiple data-driven approach for predicting landslide deformation. Landslides 17, 709–718 (2020).

Stumpf, A. & Kerle, N. Object-oriented mapping of landslides using Random Forests. Remote Sens. Environ. 115, 2564–2577 (2011).

Tanyu, B. F., Abbaspour, A., Alimohammadlou, Y. & Tecuci, G. Landslide susceptibility analyses using Random Forest, C4. 5, and C5. 0 with balanced and unbalanced datasets. Catena 203, 105355 (2021).

Ali, S. A. et al. An ensemble random forest tree with SVM, ANN, NBT, and LMT for landslide susceptibility mapping in the Rangit River watershed, India. Nat. Hazards. 113, 1601–1633 (2022).

Huang, Y. & Zhao, L. Review on landslide susceptibility mapping using support vector machines. Catena 165, 520–529 (2018).

Kavzoglu, T., Sahin, E. K. & Colkesen, I. Landslide susceptibility mapping using GIS-based multi-criteria decision analysis, support vector machines, and logistic regression. Landslides 11, 425–439 (2014).

Kavzoglu, T. & Teke, A. Advanced hyperparameter optimization for improved spatial prediction of shallow landslides using extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost). Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 81, 201 (2022).

Zhang, J. Y. et al. Insights into geospatial heterogeneity of landslide susceptibility based on the SHAP-XGBoost model. J. Environ. Manag. 332, 117357 (2023).

Azarafza, M., Azarafza, M., Akgün, H., Atkinson, P. M. & Derakhshani, R. Deep learning-based landslide susceptibility mapping. Sci. Rep. 11, 24112 (2021).

Kikuchi, T., Sakita, K., Nishiyama, S. & Takahashi, K. Landslide susceptibility mapping using automatically constructed CNN architectures with pre-slide topographic DEM of deep-seated catastrophic landslides caused by Typhoon Talas. Nat. Hazards. 117, 339–364 (2023).

Lin, Q. G. et al. National-scale data-driven rainfall induced landslide susceptibility mapping for China by accounting for incomplete landslide data. Geosci. Front. 12, 101248 (2021).

Rong, G. Z. et al. Population amount risk assessment of extreme precipitation-induced landslides based on integrated machine learning model and scenario simulation. Geosci. Front. 14, 101541 (2023).

Ye, P., Yu, B., Chen, W. H., Liu, K. & Ye, L. Z. Rainfall-induced landslide susceptibility mapping using machine learning algorithms and comparison of their performance in Hilly area of Fujian Province, China. Nat. Hazards. 113, 965–995 (2022).

Huang, F. M. et al. Regional rainfall-induced landslide hazard warning based on landslide susceptibility mapping and a critical rainfall threshold. Geomorphology 408, 108236 (2022).

Cui, H. Z., Ji, J., Hürlimann, M. & Medina, V. Probabilistic and physically-based modelling of rainfall-induced landslide susceptibility using integrated GIS-FORM algorithm. Landslides 21, 1461–1481 (2024).

Gariano, S. et al. Long-term analysis of rainfall-induced landslides in Umbria, central Italy. Nat. Hazards. 106, 2207–2225 (2021).

Kim, S. W. et al. Effect of antecedent rainfall conditions and their variations on shallow landslide-triggering rainfall thresholds in South Korea. Landslides 18, 569–582 (2021).

Kalantar, B. et al. Landslide susceptibility mapping: Machine and ensemble learning based on remote sensing big data. Remote Sens 12, 1737 (2020).

Gariano, S., Rianna, G., Petrucci, O. & Guzzetti, F. Assessing future changes in the occurrence of rainfall-induced landslides at a regional scale. Sci. Total Environ. 596, 417–426 (2017).

Agboola, G., Beni, L. H., Elbayoumi, T. & Thompson, G. Optimizing landslide susceptibility mapping using machine learning and geospatial techniques. Ecol. Inf. 81, 102583 (2024).

Gaidzik, K. & Ramirez-Herrera, M. T. The importance of input data on landslide susceptibility mapping. Sci. Rep. 11, 19334 (2021).

Ren, T. H., Gao, L. & Gong, W. P. An ensemble of dynamic rainfall index and machine learning method for spatiotemporal landslide susceptibility modeling. Landslides 21, 257–273 (2023).

Fang, Z. C., Wang, Y., van Westen, C. & Lombardo, L. G. Landslide hazard spatiotemporal prediction based on data-driven models: Estimating where, when and how large landslide may be. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 126, 103631 (2024).

Hartmann, J. & Moosdorf, N. The new global lithological map database GLiM: A representation of rock properties at the Earth surface. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GC004370 (2012).

Xu, Y. et al. A daily temperature dataset over China and its application in validating a RCM simulation. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 26, 763–772 (2009).

Wu, J. & Gao, X.-J. A gridded daily observation dataset over China region and comparison with the other datasets. Chin. J. Geophys. https://doi.org/10.6038/cjg20130406 (2013).

Wu, J., Gao, X. J., Giorgi, F. & Chen, D. L. Changes of effective temperature and cold/hot days in late decades over China based on a high resolution gridded observation dataset. Int. J. Climatol. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5038 (2016).

Li, B. H. et al. Global Dynamic Rainfall-Induced Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Machine Learning. Remote Sens 14, 5795 (2022).

Xiong, J., Pei, T. & Qiu, T. A Novel Framework for Spatiotemporal Susceptibility Prediction of Rainfall-Induced Landslides: A Case Study in Western Pennsylvania. Remote Sens 16, 3526 (2024).

Cui, W. F. et al. Interpretable machine learning incorporating major lithology for regional landslide warning in northern and eastern Guangdong. npj Nat. Hazards. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00146-8 (2025).

Selamat, S. N., Majid, N. A., Taha, M. R. & Osman, A. Landslide susceptibility model using artificial neural network (ANN) approach in Langat river basin, Selangor, Malaysia. Land 11, 833 (2022).

Benesty, J., Chen, J. D., Huang, Y. T. & Cohen, I. Noise Reduction in Speech Processing Springer Topics in Signal Processing (eds Benesty, J., Chen, J. D., Huang, Y. T. & Cohen, I) 37–40 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No.2024YFC3014100) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.42077437). The funders provided financial support for the study. We gratefully acknowledge the Ministry of Natural Resources of China for providing valuable resources and support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Wang. wrote the original draft, developed the methodology, conducted the formal analysis, and prepared the visualizations. J.Wu. conceptualized the study, supervised the research, reviewed and edited the manuscript, and acquired the funding. H.F. contributed to data preparation and reviewed the manuscript. M.W. reviewed the manuscript, participated in the discussion of the study, and contributed to funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Wu, J., Fang, H. et al. Incorporating compound temporal precipitation dynamics to enhance landslide susceptibility modeling. npj Nat. Hazards 3, 18 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-026-00181-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-026-00181-z