Abstract

This review summarizes findings on the role of sleep and circadian rhythm disruption in perinatal anxiety. Sleep disruption is concurrently and prospectively associated with anxiety in pregnancy and postpartum. Findings on circadian rhythm disruption and perinatal anxiety are mixed. Treatments targeting sleep may be most beneficial for reducing anxiety symptoms when delivered during pregnancy. Extant findings suggest sleep and circadian rhythms play a role in perinatal anxiety and its treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Associations between sleep and circadian rhythm disruption and perinatal anxiety

The perinatal period is both a momentous time of joy and excitement and a time of risk for psychopathology. Considerable research has examined depression in the perinatal period, revealing high prevalence rates (26.3%)1, well-established risk factors, including low social support, physical health conditions, and sleep disruption1,2, and adverse effects on infant outcomes3,4. In contrast, much less attention has been given to perinatal anxiety. This relative paucity of research is particularly notable given the high prevalence of perinatal anxiety. Approximately 15% of women experience an anxiety disorder during pregnancy5,6, and 9–17% experience an anxiety disorder during postpartum5,6,7. Rates are even higher in some specific anxiety disorders. For example, approximately 9% of women will develop OCD within the first 6 months postpartum8, a prevalence rate substantially higher than the ~1% 12-month prevalence of OCD in the general population9. Further, 15–24% of perinatal women experience clinically significant anxiety symptoms5,10, and many women report new or worsening anxiety symptoms during the postpartum period7,10. Thus, the perinatal period represents a unique risk window for anxiety symptoms and disorders, which may contribute to the higher rates of anxiety disorders observed for women compared to men11.

The high prevalence of perinatal anxiety is an important public health issue, as perinatal anxiety is associated with a range of adverse maternal and infant outcomes. For mothers, perinatal anxiety is associated with comorbid eating disorders12, suicide risk13, and higher childbirth fear14. Perinatal anxiety is also associated with adverse outcomes for infants both proximally and distally to delivery. In the near-term, perinatal anxiety is associated with adverse infant obstetric outcomes, such as risk for pre-term birth15, lower Apgar scores (an assessment of infant health performed shortly after delivery, where lower scores may indicate need for medical attention)16, higher likelihood of birth complications16, and lower likelihood of breastfeeding and shorter breastfeeding duration17,18. Notably, these relations are observed over and above relevant covariates such as medical risk15, age, and parity15,18. In the long term, perinatal anxiety is associated with adverse emotional and behavioral health outcomes for the child. For example, postpartum anxiety is associated with lower social-emotional development in children at age 2 years19, anxiety during pregnancy is associated with higher internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children at ages 8–9 years20, and anxiety during pregnancy is associated with higher impulsivity in children at ages 14–15 years21. Thus, perinatal anxiety is associated with worse emotional and behavioral trajectories for children, and these effects can be observed into the teenage years. These trajectories may be due in part to the consequences of perinatal anxiety on early maternal caregiving behaviors; indeed, perinatal anxiety is associated with lower maternal-infant bonding22 and lower maternal responsivity to the infant23.

Sleep and circadian rhythm disruption: candidate risk factors

The high prevalence rates and associated consequences of perinatal anxiety symptoms and disorders highlight the need to identify modifiable predictors that could be targeted for treatment. However, despite being more common than perinatal depression6, perinatal anxiety remains understudied24,25, and risk factors for perinatal anxiety are not well-delineated. One candidate predictor of perinatal anxiety is sleep and circadian rhythm disruption. Sleep plays a crucial role in cognitive and emotional functioning26,27. Sleep disruption can refer to disruptions to the continuity of sleep, such as insufficient sleep duration and low sleep efficiency (i.e., the ratio of sleep duration to time spent in bed), the architecture of sleep (i.e., time spent in stages of sleep, defined in part by electrical activity in the brain), or subjective aspects of sleep, such as insomnia symptoms (i.e., subjective difficulties with sleep initiation and maintenance) and perceived sleep quality. In the perinatal literature, assessment of sleep has largely focused on subjective sleep duration, sleep quality, and insomnia symptoms, though some studies have used objective measures such as actigraphy and polysomnography. Human physiology and behavior, including sleep, vary across the 24-h day in a rhythmic pattern driven by the endogenous circadian clock. Circadian rhythm disruption may be indicated by the timing, amplitude, and/or alignment of markers of the circadian clock. Timing of the circadian clock can be assessed using biomarkers such as melatonin28, or estimated using indicators such as sleep timing and chronotype (individual differences in the temporal organization of behavior29). The circadian clock is entrained by light exposure30; thus, assessment of light may also provide insight into circadian rhythm disruption.

Notably, changes in sleep and circadian rhythms are characteristic of the perinatal period. Studies using subjective measures of sleep suggest that insomnia symptoms increase and sleep quality decreases from early to late pregnancy31,32. Studies using objective measures further find that sleep duration, sleep efficiency, and time spent in deep stages of sleep decrease across pregnancy33,34 followed by a sharp reduction in sleep duration in the early postpartum period due to infant caregiving demands34,35. Extant findings also suggest changes in markers of circadian rhythms during the perinatal period, though findings are less consistent than those observed for sleep. Relative to pre-pregnancy, bedtimes shift earlier across pregnancy36. Studies of sleep timing in postpartum offer mixed results: One study found that wake time was significantly later in the first 2–4 weeks postpartum compared to the third trimester of pregnancy and subsequently significantly earlier at 12–16 weeks and 12–15 months37, whereas another study found that both bedtimes and waketimes, as well as chronotype, shifted progressively earlier across 24 months postpartum compared to the third trimester of pregnancy38. However, in the absence of circadian biomarkers, changes in sleep timing in pregnancy could reflect alterations to the homeostatic sleep drive, and changes in sleep timing in the postpartum could reflect changes in the allocation of sleep to compensate for sleep loss during nocturnal caregiving. Importantly, melatonin, the primary biomarker of the timing of the human circadian clock, does exhibit changes during the perinatal period. Total melatonin output increases across pregnancy and decreases substantially following delivery39,40. Changes in melatonin output may contribute to changes in melatonin amplitude, though amplitude was not assessed in these studies. However, one study comparing postpartum women 4–10 weeks following delivery to nulliparous controls also found lower melatonin output, including lower percent rise relative to baseline41, suggesting blunted melatonin amplitude. Only one study to date has examined change in circadian melatonin phase during the perinatal period, finding that melatonin onset was delayed by ~42 min from the third trimester to 6 weeks postpartum, and the phase angle between sleep onset and DLMO shortened42, suggesting increased circadian misalignment.

The extant literature indicates that the perinatal period is a time of risk for sleep and circadian rhythm disruption and new or worsening anxiety. The adverse consequences of perinatal anxiety for both mother and infant highlight the need to identify modifiable risk factors for perinatal anxiety. Given the considerable research linking sleep and circadian rhythm disruption to anxiety in the general population43, this review considers the extant research linking sleep and circadian rhythm disruption to perinatal anxiety and applications of behavioral sleep and circadian medicine in the perinatal period (see Supplementary Table 1 for summaries of individual studies reviewed).

Associations between sleep and circadian rhythm disruption and anxiety in pregnancy

Several studies have found a concurrent association between subjective sleep disruption and anxiety during pregnancy, with the most consistent link observed in late pregnancy. Indeed, higher anxiety is associated with longer sleep onset latency44,45, more nocturnal awakenings45, lower sleep quality45,46, greater global sleep disturbance47, and higher insomnia symptoms48 in the third trimester of pregnancy. In the second trimester, some studies show that higher anxiety is associated with greater global sleep disturbance49 and higher insomnia symptoms50; however, other studies have found no association between anxiety and global sleep disturbance45 or sleep quality46 in the second trimester. Finally, higher anxiety is associated with shorter sleep duration51 and greater global sleep disturbances49 in the first trimester. Further, studies that have examined the association between subjective sleep disruption and anxiety across all 3 trimesters have found that higher anxiety is associated with shorter sleep duration, lower sleep quality52, and higher insomnia symptoms53.

Notably, these associations are observed in both healthy and community (i.e., including those with and without physical and/or mental health conditions) pregnant women, suggesting the link between subjective sleep disruption and anxiety is not fully accounted for by existing pathology. Similar effects are, however, observed in clinical samples, as higher insomnia symptoms are associated with higher worry in pregnant women seeking psychiatric care54, and pregnant women with stress-related sleep disturbance are more likely to screen positive for generalized anxiety disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder55.

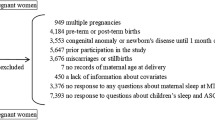

In contrast, the few studies that have used objective sleep measures (i.e., actigraphy) found no association between objective sleep and anxiety during pregnancy47,56,57. It is possible that the association between sleep disruption and anxiety during pregnancy is more strongly linked to subjective aspects of sleep, such as perceived quality, versus aspects of sleep continuity that are measured by actigraphy. Alternatively, subjective sleep disruption may represent a combination of actual sleep and psychological distress57, which may explain the discrepancies observed for subjective versus objective sleep and anxiety. Additional work using both subjective and objective measures of sleep is needed to understand these discrepant findings. Likewise, few studies have examined indicators of circadian rhythm disruption as correlates of anxiety during pregnancy. One study that measured chronotype found no association with anxiety in late pregnancy44. Another study found no association between self-reported light exposure and anxiety, although there was an association between greater evening light exposure and higher perceived stress in the third trimester46. See Fig. 1.

Prospective associations between sleep and circadian rhythm disruption in pregnancy and anxiety in postpartum

There is also a consistent prospective relation observed between insomnia symptoms in pregnancy and postpartum anxiety. Insomnia during pregnancy predicts increased postpartum general anxiety48,50,58, as well as postpartum OCD50 and PTSD symptoms59. Similarly, trajectory analyses indicate that perinatal women with an insomnia trajectory report higher postpartum anxiety than women in the subthreshold or no insomnia trajectory groups60. Three of these studies also examined the effects of insomnia during pregnancy on obstetric outcomes and found that women with insomnia during pregnancy were no more likely to have a cesarean section than women without insomnia during pregnancy, suggesting the links between insomnia in pregnancy and anxiety in postpartum are not better accounted for by obstetric risk48,50,58.

Findings regarding a prospective relation between other aspects of sleep disruption in pregnancy and postpartum anxiety are less consistent. Though some studies have shown a prospective relation between lower sleep quality in pregnancy and higher postpartum anxiety61,62, one study did not observe this effect over and above the effects of education and anxiety during pregnancy63. Similarly, though only two studies have specifically examined the prospective relation between sleep duration in pregnancy and postpartum anxiety, findings are mixed38,62. Further, two smaller studies (i.e., N < 50) of healthy women found no association between sleep disruption in pregnancy and postpartum anxiety56,57, suggesting the existence of factors that may make women more vulnerable to the effects of sleep disruption in pregnancy on postpartum anxiety.

Evidence for an association between circadian rhythm disruption in pregnancy and postpartum anxiety is also mixed. One study of women with a history of a mood disorder found no association between sleep timing in pregnancy and postpartum OCD symptoms, but did find that a longer phase angle in pregnancy (i.e., later sleep timing relative to circadian phase, measured by dim light melatonin onset) was associated with higher postpartum OCD symptoms64. In contrast, a study of healthy women found no prospective relation between chronotype in pregnancy and postpartum anxiety. These findings suggest that physiological measures of circadian rhythms (e.g., melatonin phase) may be needed to reveal potential effects of circadian rhythm disruption on postpartum anxiety in vulnerable women. See Fig. 2.

Summary of associations between sleep and circadian rhytm disruption in pregnancy and postpartum anxiety (A) and associations between postpartum sleep and circadian rhythm disruption and anxiety (B). Arrows (↑↓) indicate significant findings, X indicates null findings, and ? indicates mixed findings.

Associations between sleep and circadian rhythm disruption and anxiety in postpartum

Fewer studies have examined the associations between sleep and circadian rhythm disruption and anxiety in the postpartum period, but findings similarly point to an association between sleep disruption and higher anxiety. In women with a history of depression, greater global sleep disturbance is associated with higher anxiety from 1 to 6 months postpartum65, and shorter subjective sleep duration is associated with higher anxiety, particularly during the early postpartum period66; however, sleep duration did not prospectively predict postpartum anxiety66. Further, women with consistently high subjective sleep disturbance up to 6 months postpartum report higher anxiety than women with low or increasing sleep disturbance trajectories67. In contrast to the lack of evidence for an association between objective sleep and anxiety in pregnancy, higher objective wake after sleep onset (i.e., time spent awake after initially falling asleep) predicts higher anxiety symptoms in the postpartum period, though this effect was at trend-level68. There is also preliminary evidence for a link between circadian rhythm disruption and postpartum anxiety. One study that used multiple methods of assessment of sleep and circadian rhythms found that greater subjective biological rhythm disruption and higher mean activity at night (i.e., higher average nocturnal activity measured by actigraphy) were associated with higher anxiety from 1 to 12 weeks postpartum. This study also found earlier mean light exposure timing (i.e., time at which average light exposure is centered) was associated with higher anxiety, specifically at 6–12 weeks postpartum69. In contrast, one study found no association between sleep timing and anxiety in postpartum women66. These findings highlight the need for additional work to understand the role of sleep and circadian rhythm disruption in anxiety during the postpartum period. See Fig. 2.

Potential mechanisms linking sleep and circadian rhythm disruption to perinatal anxiety

Sleep and circadian rhythm disruption have known downstream consequences for physiological, cognitive, and affective function70,71,72. These consequences may point to putative mechanisms by which sleep and circadian rhythm disruption contribute to perinatal anxiety. Circadian misalignment occurs when there is a mismatch between the circadian clock and social demands and/or desynchrony between central (i.e., brain) and peripheral (e.g., liver, muscle, etc.) clocks73. Exposure to light, the primary time cue for the central circadian clock in humans, at night (e.g., during nocturnal caregiving) may contribute to circadian misalignment by delaying the circadian clock. Multiple theoretical mechanisms of anxiety-related disorders, such as monoamine signaling and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function, are under circadian control and/or interface with the circadian system71. Findings from the animal literature also show that circadian misalignment during pregnancy results in alterations in maternal hormone rhythms and circadian gene expression and has adverse consequences for offspring74. Thus, the physiological consequences of circadian rhythm disruption may in turn contribute to anxiety in the perinatal period.

Sleep is theorized to function to consolidate and organize information accumulated during the waking day through long-term synaptic potentiation, a process known as synaptic homeostasis75. In the absence of sufficient sleep, synaptic overload may then contribute to deficits in cognitive and emotional function due in part to decreased neuronal signal-to-noise ratios and reduced plasticity75. These cognitive and emotional impairments of sleep disruption have been well-documented in the general population. For example, prior work has demonstrated that sleep loss results in deficits in inhibitory control76 and memory encoding77, as well as increased emotional reactivity to negative stimuli78 and higher subjective stress to stressors79. The known disruptions to sleep experienced by perinatal women may therefore have similar downstream consequences that confer vulnerability for anxiety. See Fig. 3.

Notably, sleep and circadian rhythm disruption are characteristic of the perinatal period, whereas clinically significant anxiety is relatively more rare80,81. Possible explanations for this imbalance come from the 3P model of insomnia, which proposes that chronic insomnia arises from a combination of predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors82. Indeed, pregnancy and childbirth are common precipitating factors for developing insomnia83,84. Predisposing factors refer to individual differences that increase vulnerability for insomnia, for example, personality traits such as neuroticism. Further, there are individual differences in sensitivity to sleep and circadian rhythm disruption, which may confer vulnerability for perinatal anxiety. Indeed, prior work in healthy adults has demonstrated that sensitivity to the consequences of sleep deprivation and circadian misalignment for cognitive performance is trait-like80,81. Perpetuating factors refer to behaviors engaged in to compensate for sleep loss that maintain insomnia over time. For example, daytime napping, a common compensatory strategy for sleep fragmentation due to nocturnal caregiving, is associated with more wake after sleep onset in postpartum women85. Further, though few studies have characterized personal light exposure in the perinatal period, extant findings suggest postpartum women are exposed to insufficient intensities of daytime light86, which may exacerbate sleep and circadian rhythm disruption. Thus, the extant literature offers several factors that may increase vulnerability to and/or amplify the negative effects of sleep and circadian rhythm disruption, which may in turn contribute to perinatal anxiety.

Implications of maternal sleep disruption for infant outcomes

As noted above, it is well-established that maternal anxiety during pregnancy and postpartum is associated with adverse outcomes for infant physical and mental health15,16,19,20. Likewise, maternal sleep and circadian rhythm disruption are associated with adverse infant outcomes. Worse subjective maternal sleep disruption during pregnancy predicts worse infant sleep at age 187, although one study did not detect this predictive effect when infant sleep was assessed at 6 weeks postpartum88. Likewise, worse subjective89,90 and objective91,92 postpartum maternal sleep is associated with worse infant sleep, particularly during the early postpartum months93. Maternal sleep disruption during pregnancy94 and postpartum95,96,97 has also been associated with a more difficult infant temperament95. Further, later objective maternal sleep timing and higher maternal intra-daily variability in diurnal activity rhythms during pregnancy predict higher externalizing symptoms in infants at age 187, and insomnia during pregnancy predicts worse social-emotional development in children at age 298.

Downstream effects of maternal sleep and circadian rhythm disruption on infant outcomes may occur through physiological mechanisms, such as neurodevelopment99. For example, objective sleep irregularity and later sleep timing during pregnancy predict smaller total cortical gray and white matter values and smaller subcortical gray matter volumes, respectively, in neonates100. Another non-mutually exclusive possibility is that maternal sleep and circadian rhythm disruption influence infant outcomes through behavioral pathways. Indeed, postpartum insomnia is associated with lower maternal-infant bonding90, and lower postpartum sleep regularity and later sleep timing are associated with lower objectively rated parenting quality101.

Effects of behavioral sleep and circadian medicine on perinatal anxiety

The consistent link between perinatal insomnia and anxiety symptoms suggests the utility of treatments targeting insomnia symptoms to reduce perinatal anxiety. Cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia (CBTI) is a behavioral sleep medicine treatment that is effective at reducing insomnia symptoms in the general population102 and in the perinatal period103. In addition to treating insomnia, CBTI has also been shown to reduce anxiety in the general population104,105. However, evidence for anxiety reduction following CBTI during the perinatal period varies by study sample and time of treatment delivery. In pregnant women with insomnia, CBTI delivered during pregnancy yields medium to large improvements in subjective106,107 and objective107 sleep during pregnancy and medium reductions in anxiety during pregnancy. Further, improvements in insomnia as a result of CBTI during pregnancy are associated with reductions in perseverative thinking108. In contrast, one study that delivered CBTI in pregnancy and postpartum to women with elevated insomnia symptoms found no effect of CBTI on postpartum anxiety symptoms109, and another study that delivered CBTI to postpartum women with insomnia likewise found no effect on postpartum anxiety110. Further, a study that delivered CBTI in pregnancy and postpartum to healthy women also found no effect on anxiety symptoms in late pregnancy or postpartum111. Together, these findings suggest that improving insomnia symptoms through CBTI may be most beneficial for anxiety symptom reduction among women with clinical insomnia during pregnancy, but less impactful for postpartum anxiety symptoms in women with less severe sleep disruption.

Light therapy is a chronotherapy involving the application of timed light exposure, commonly morning bright light112. Although prior work suggests that light therapy is effective for reducing perinatal depression symptoms113, the efficacy of light therapy for perinatal anxiety is unclear. One study of postpartum women with insomnia who were instructed to complete 20 min of light therapy each morning and minimize evening light exposure found no significant change in anxiety compared to treatment as usual (i.e., routine care)110. However, no study has examined the effect of light therapy on perinatal anxiety in women with an anxiety disorder, although there is preliminary evidence that longer doses (e.g., 1 h) of light therapy reduce anxiety symptoms in adults with anxiety-related disorders in the general population114,115.

Opportunities for behavioral sleep and circadian medicine in the perinatal period

Though mixed, the extant findings suggest that directly targeting sleep disruption may have some anxiety-reducing effects in the perinatal period. Behavioral sleep and circadian medicine may be particularly desirable during the perinatal period, as pregnant women report preferring CBTI to medication or acupuncture for the treatment of insomnia116. Further, stigma and concerns about being perceived as an “unfit mother” are identified as being barriers to seeking treatment for perinatal anxiety117,118; thus, treatments targeting sleep and circadian rhythms may offer an easier point of entry to mental health care for perinatal women. However, recent findings also suggest there is a need for improvement in the application of sleep and circadian medicine to the perinatal period. For example, qualitative patient feedback provided after a trial of digital CBTI for pregnant women with insomnia revealed that women found the treatment was limited by a lack of tailoring to the specific challenges of the perinatal period108. Thus, future work is needed to assess the utility of sleep and circadian medicine treatments tailored for the perinatal period for improving perinatal anxiety.

Conclusions and future directions

The strength of the association between sleep disruption and perinatal anxiety varies by assessment period, sleep measure, and study sample. In pregnancy, subjective sleep disruption is most consistently linked to higher anxiety in the third trimester, and insomnia symptoms, relative to other sleep indicators, are the most robust correlate of anxiety. There is also consistent evidence that insomnia symptoms in pregnancy predict postpartum anxiety symptoms, whereas findings for prediction by sleep quality and duration are mixed. The few studies that have examined prospective relations between postpartum sleep disruption and anxiety find that both subjective and objective measures of sleep disruption predict higher postpartum anxiety. Across the perinatal period, studies that have found no association between sleep disruption and anxiety have largely examined healthy women, suggesting that physical or mental health risk factors may amplify the effects of sleep disruption on perinatal anxiety. Similarly, studies examining the efficacy of CBTI in the perinatal period suggest potential utility of intervening on insomnia symptoms to reduce anxiety during pregnancy among those with clinical insomnia, whereas these benefits may not extend to the postpartum period or to women with less disturbed sleep.

In contrast, the extant research examining associations between circadian rhythm disruption and perinatal anxiety is limited, and findings are mixed. At present, there is no evidence that later chronotype or later sleep timing are associated with perinatal anxiety. However, studies using objective measures reveal associations between perinatal anxiety and circadian phase angle, diurnal activity rhythms, and light exposure. These findings suggest that there is more to be learned about the potential role of circadian rhythms in perinatal anxiety.

Future work in this area is needed to address the limitations of the extant research. One notable issue is the reliance on general measures of anxiety versus perinatal-specific measures, which may underestimate the effect of sleep disruption on perinatal anxiety. For example, prior work suggests that the prevalence of perinatal OCD is underestimated in the absence of assessing perinatal-specific symptoms8. Similarly, few studies have used objective measures of sleep and circadian rhythm disruption. Although subjective measures are more feasible, particularly in this difficult-to-recruit population, wearables offer a relatively low-burden objective measure that can provide insight into multiple indicators of sleep and circadian rhythm disruption, including sleep/wake, diurnal activity rhythms, and personal light exposure. Further, none of the studies reviewed here examined the role of the distribution of caregiving responsibilities, which could moderate the reported effects in the postpartum period. Another limitation of the extant research is the dearth of studies in clinical samples. No study has examined the role of sleep and circadian rhythm disruption in perinatal anxiety in women with an anxiety disorder, at risk for an anxiety disorder, or with a history of an anxiety disorder. The majority of the work reviewed here was conducted in healthy or community samples, though a few studies examined women with a history of depression or women with insomnia. Thus, the degree to which these findings extend to women with clinically significant anxiety is unknown, representing an important question for future research.

Despite these limitations, the work conducted in this area also has several strengths, including the frequent use of longitudinal designs and large sample sizes. The extant literature suggests that sleep disruption is associated with perinatal anxiety both concurrently and prospectively. In contrast, there is insufficient evidence for a similar association between circadian rhythm disruption and perinatal anxiety, though the few studies using objective measures suggest more work in this area is needed. Behavioral sleep medicine approaches, such as CBTI, offer novel, nonpharmacological treatments for sleep disruption during pregnancy. Thus, sleep and circadian health may represent an important perspective from which to understand perinatal anxiety.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Al-abri, K., Edge, D. & Armitage, C. J. Prevalence and correlates of perinatal depression. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 58, 1581–1590 (2023).

Dagher, R. K., Bruckheim, H. E., Colpe, L. J., Edwards, E. & White, D. B. Perinatal depression: challenges and opportunities. J. Womens Health 30, 154–159 (2021).

Fan, X. et al. Perinatal depression and infant and toddler neurodevelopment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2024.105579 (2024).

Rogers, A. et al. Association between maternal perinatal depression and anxiety and child and adolescent development: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 174, 1082–1092 (2020).

Dennis, C. L., Falah-Hassani, K. & Shiri, R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 210, 315–323 (2017).

Fairbrother, N., Janssen, P., Antony, M. M., Tucker, E. & Young, A. H. Perinatal anxiety disorder prevalence and incidence. J. Affect. Disord. 200, 148–155 (2016).

Goodman, J. H., Watson, G. R. & Stubbs, B. Anxiety disorders in postpartum women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 203, 292–331 (2016).

Fairbrother, N. et al. High prevalence and incidence of OCD among women across pregnancy and the postpartum. J. Clin. Psychiatry 82, 20m13398 (2021).

Ruscio, A. M., Stein, D. J., Chiu, W. T. & Kessler, R. C. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol. Psychiatry 15, 53–63 (2010).

Wenzel, A., Haugen, E. N., Jackson, L. C. & Brendle, J. R. Anxiety symptoms and disorders at eight weeks postpartum. J. Anxiety Disord. 19, 295–311 (2005).

McLean, C. P., Asnaani, A., Litz, B. T. & Hofmann, S. G. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J. Psychiatr. Res 45, 1027–1035 (2011).

Micali, N., Simonoff, E. & Treasure, J. Pregnancy and post-partum depression and anxiety in a longitudinal general population cohort: the effect of eating disorders and past depression. J. Affect. Disord. 131, 150–157 (2011).

Farias, D. R. et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the first trimester of pregnancy and factors associated with current suicide risk. Psychiatry Res. 210, 962–968 (2013).

Hall, W. A. et al. Childbirth fear, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep deprivation in pregnant women. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 38, 567–576 (2009).

Staneva, A., Bogossian, F., Pritchard, M. & Wittkowski, A. The effects of maternal depression, anxiety, and perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth: a systematic review. Women Birth 28, 179–193 (2015).

Dowse, E. et al. Impact of perinatal depression and anxiety on birth outcomes: a retrospective data analysis. Matern. Child Health J. 24, 718–726 (2020).

Fallon, V., Groves, R., Halford, J. C. G., Bennett, K. M. & Harrold, J. A. Postpartum anxiety and infant-feeding outcomes: a systematic review. J. Hum. Lact. 32, 740–758 (2016).

Paul, I. M., Downs, D. S., Schaefer, E. W., Beiler, J. S. & Weisman, C. S. Postpartum anxiety and maternal-infant health outcomes. Pediatrics 131, e1218–e1224 (2013).

Polte, C. et al. Impact of maternal perinatal anxiety on social-emotional development of 2-year-olds, a prospective study of Norwegian mothers and their offspring: the impact of perinatal anxiety on child development. Matern. Child Health J. 23, 386–396 (2019).

Van Den Bergh, B. R. H. & Marcoen, A. High antenatal maternal anxiety is related to ADHD symptoms, externalizing problems, and anxiety in 8- and 9-year-olds. Child. Rev. 75, 1085–1097 (2004).

Van Den Bergh, B. R. H. et al. High antenatal maternal anxiety is related to impulsivity during performance on cognitive tasks in 14- and 15-year-olds. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 29, 259–269 (2005).

Fallon, V., Silverio, S. A., Halford, J. C. G., Bennett, K. M. & Harrold, J. A. Postpartum-specific anxiety and maternal bonding: further evidence to support the use of childbearing specific mood tools. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 39, 114–124 (2021).

Miller, M. L. & O’Hara, M. W. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms, intrusive thoughts and depressive symptoms: a longitudinal study examining relation to maternal responsiveness. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 38, 226–242 (2020).

Field, T. Postnatal anxiety prevalence, predictors and effects on development: a narrative review. Infant Behav. Dev. 51, 24–32 (2018).

Pawluski, J. L., Lonstein, J. S. & Fleming, A. S. The neurobiology of postpartum anxiety and depression. Trends Neurosci. 40, 106–120 (2017).

Tempesta, D., Socci, V., De Gennaro, L. & Ferrara, M. Sleep and emotional processing. Sleep Med. Rev. 40, 183–195 (2018).

Hobson, J. A. Sleep is of the brain, by the brain and for the brain. Nature 437, 1254–1256 (2005).

Broussard, J. L. et al. Circadian rhythms versus daily patterns in human physiology and behavior. In Biological Timekeeping: Clocks, Rhythms, and Behaviour (ed. Kumar, V.) 279–295 (Springer India, 2017).

Roenneberg, T., Wirz-Justice, A. & Merrow, M. Life between clocks: Daily temporal patterns of human chronotypes. J. Biol. Rhythms 18, 80–90 (2003).

Golombek, D. A. & Rosenstein, R. E. Physiology of circadian entrainment. Physiol. Rev. 90, 1063–1102 (2010).

Sedov, I. D., Cameron, E. E., Madigan, S. & Tomfohr-Madsen, L. M. Sleep quality during pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 38, 168–176 (2018).

Sedov, I. D., Anderson, N. J., Dhillon, A. K. & Tomfohr-Madsen, L. M. Insomnia symptoms during pregnancy: a meta-analysis. J. Sleep Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13207 (2021).

Guo, Y., Xu, Q., Dutt, N., Kehoe, P. & Qu, A. Longitudinal changes in objective sleep parameters during pregnancy. Womens Health 19, 1–8 (2023).

Lee, K. A., Zaffke, M. E. & McEnany, G. Parity and sleep patterns during and after pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 95, 14–18 (2000).

Horwitz, A. et al. Sleep of mothers, fathers, and infants: a longitudinal study from pregnancy through 12 months. Sleep 46, 1–16 (2023).

Zhao, P. et al. Sleep behavior and chronotype before and throughout pregnancy. Sleep Med. 94, 54–62 (2022).

Wolfson, A. R. et al. Changes in sleep patterns and depressive symptoms in first-time mothers: Last trimester to 1-year postpartum. Behav. Sleep Med. 1, 54–67 (2003).

Verma, S., Pinnington, D. M., Manber, R. & Bei, B. Sleep–wake timing and chronotype in perinatal periods: longitudinal changes and associations with insomnia symptoms, sleep-related impairment, and mood from pregnancy to 2 years postpartum. J. Sleep Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.14021 (2023).

Ejaz, H., Figaro, J. K., Woolner, A. M. F., Thottakam, B. M. V. & Galley, H. F. Maternal serum melatonin increases during pregnancy and falls immediately after delivery implicating the placenta as a major source of melatonin. Front. Endocrinol. 11, 623038 (2021).

Nakamura, Y. et al. Changes of serum melatonin level and its relationship to feto-placental unit during pregnancy. J. Pineal Res. 30, 29–33 (2001).

Thomas, K. A. & Burr, R. L. Melatonin level and pattern in postpartum versus nonpregnant nulliparous women. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 35, 608–615 (2006).

Sharkey, K. M., Pearlstein, T. B. & Carskadon, M. A. Circadian phase shifts and mood across the perinatal period in women with a history of major depressive disorder: a preliminary communication. J. Affect. Disord. 150, 1103–1108 (2013).

Cox, R. C. & Olatunji, B. O. Sleep in the anxiety-related disorders: A meta-analysis of subjective and objective research. Sleep Med. Rev. 51, 101282 (2020).

Loret de Mola, C. et al. Sleep and its association with depressive and anxiety symptoms during the last weeks of pregnancy: a population-based study. Sleep Health 9, 482–488 (2023).

Polo-Kantola, P., Aukia, L., Karlsson, H., Karlsson, L. & Paavonen, E. J. Sleep quality during pregnancy: associations with depressive and anxiety symptoms. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 96, 198–206 (2017).

Ng, C. M. et al. Sleep, light exposure at night, and psychological wellbeing during pregnancy. BMC Public Health 23, 1803 (2023).

Volkovich, E., Tikotzky, L. & Manber, R. Objective and subjective sleep during pregnancy: links with depressive and anxiety symptoms. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 19, 173–181 (2016).

Palagini, L. et al. Prenatal insomnia disorder may predict concurrent and postpartum psychopathology: a longitudinal study. J. Sleep Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.14202 (2024).

Song, B. et al. Physical activity and sleep quality among pregnant women during the first and second trimesters are associated with mental health and adverse pregnancy outcomes. BMC Womens Health 24, (2024).

Osnes, R. S. et al. Mid-pregnancy insomnia is associated with concurrent and postpartum maternal anxiety and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: a prospective cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 266, 319–326 (2020).

van der Zwan, J. E. et al. Longitudinal associations between sleep and anxiety during pregnancy, and the moderating effect of resilience, using parallel process latent growth curve models. Sleep Med. 40, 63–68 (2017).

Yu, Y. et al. Sleep was associated with depression and anxiety status during pregnancy: a prospective longitudinal study. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 20, 695–701 (2017).

Aukia, L. et al. Insomnia symptoms increase during pregnancy, but no increase in sleepiness - associations with symptoms of depression and anxiety. Sleep Med. 72, 150–156 (2020).

Swanson, L. M., Pickett, S. M., Flynn, H. & Armitage, R. Relationships among depression, anxiety, and insomnia symptoms in perinatal women seeking mental health treatment. J. Womens Health 20, 553–558 (2011).

Sanchez, S. E. et al. Association of stress-related sleep disturbance with psychiatric symptoms among pregnant women. Sleep Med. 70, 27–32 (2020).

Bei, B., Milgrom, J., Ericksen, J. & Trinder, J. Subjective perception of sleep, but not its objective quality, is associated with immediate postpartum mood disturbances in healthy women. Sleep 33, 531–538 (2010).

Coo Calcagni, S., Bei, B., Milgrom, J. & Trinder, J. The relationship between sleep and mood in first-time and experienced mothers. Behav. Sleep Med. 10, 167–179 (2012).

Osnes, R. S., Roaldset, J. O., Follestad, T. & Eberhard-Gran, M. Insomnia late in pregnancy is associated with perinatal anxiety: a longitudinal cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 248, 155–165 (2019).

Deforges, C., Noël, Y., Eberhard-Gran, M., Garthus-Niegel, S. & Horsch, A. Prenatal insomnia and childbirth-related PTSD symptoms: a prospective population-based cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 295, 305–315 (2021).

Sedov, I. D. & Tomfohr-Madsen, L. M. Trajectories of insomnia symptoms and associations with mood and anxiety from early pregnancy to the postpartum. Behav. Sleep Med. 19, 395–406 (2021).

Okun, M. L., Mancuso, R. A., Hobel, C. J., Schetter, C. D. & Coussons-Read, M. Poor sleep quality increases symptoms of depression and anxiety in postpartum women. J. Behav. Med. 41, 703–710 (2018).

Basu, A. et al. An examination of sleep as a protective factor for depression and anxiety in the perinatal period: novel causal analyses in a prospective pregnancy cohort. Am. J. Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwae349/7755081 (2024).

Tham, E. K. H. et al. Associations between poor subjective prenatal sleep quality and postnatal depression and anxiety symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 202, 91–94 (2016).

Obeysekare, J. L. et al. Delayed sleep timing and circadian rhythms in pregnancy and transdiagnostic symptoms associated with postpartum depression. Transl. Psychiatry 14, 4–11 (2020).

Okun, M. L. & Lac, A. Postpartum insomnia and poor sleep quality are longitudinally predictive of postpartum mood symptoms. Psychosom. Med. 85, 736–743 (2023).

Cox, R. C., Aylward, B. S., Macarelli, I. & Okun, M. L. Concurrent and prospective associations between sleep duration and timing and postpartum anxiety symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 119523 (2025).

Tomfohr, L. M., Buliga, E., Letourneau, N. L., Campbell, T. S. & Giesbrecht, G. F. Trajectories of sleep quality and associations with mood during the perinatal period. Sleep 38, 1237–1245 (2015).

Gueron-Sela, N., Shahar, G., Volkovich, E. & Tikotzky, L. Prenatal maternal sleep and trajectories of postpartum depression and anxiety symptoms. J. Sleep Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13258 (2020).

Slyepchenko, A., Minuzzi, L., Reilly, J. P. & Frey, B. N. Longitudinal changes in sleep, biological rhythms, and light exposure from late pregnancy to postpartum and their impact on peripartum mood and anxiety. J. Clin. Psychiatry 83, 21m13991 (2022).

Harvey, A. G., Murray, G., Chandler, R. A. & Soehner, A. Sleep disturbance as transdiagnostic: consideration of neurobiological mechanisms. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31, 225–235 (2011).

McClung, C. A. How might circadian rhythms control mood? Let me count the ways. Biol. Psychiatry 74, 242–249 (2013).

Meyer, N. et al. The sleep-circadian interface: a window into mental disorders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2214756121 (2024).

Chaput, J. P. et al. The role of insufficient sleep and circadian misalignment in obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 19, 82–97 (2023).

Logan, R. W. & McClung, C. A. Rhythms of life: circadian disruption and brain disorders across the lifespan. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 49–65 (2019).

Tononi, G. & Cirelli, C. Sleep function and synaptic homeostasis. Sleep Med. Rev. 10, 49–62 (2006).

Drummond, S. P. A., Paulus, M. P. & Tapert, S. F. Effects of two nights sleep deprivation and two nights recovery sleep on response inhibition. J. Sleep Res. 15, 261–265 (2006).

Cousins, J. N., Sasmita, K. & Chee, M. W. L. Memory encoding is impaired after multiple nights of partial sleep restriction. J. Sleep Res. 27, 138–145 (2018).

Reddy, R., Palmer, C. A., Jackson, C., Farris, S. G. & Alfano, C. A. Impact of sleep restriction versus idealized sleep on emotional experience, reactivity and regulation in healthy adolescents. J. Sleep Res. 26, 516–525 (2017).

Minkel, J. D. et al. Sleep deprivation and stressors: evidence from elevated negative affect in response to mild stressors when sleep deprived. Emotion 12, 1015–1020 (2014).

Galli, O., Jones, C. W., Larson, O., Basner, M. & Dinges, D. F. Predictors of interindividual differences in vulnerability to neurobehavioral consequences of chronic partial sleep restriction. Sleep 1, 14 (2022).

Sprecher, K. E. et al. Trait-like vulnerability of higher-order cognition and ability to maintain wakefulness during combined sleep restriction and circadian misalignment. Sleep 42, 1–15 (2019).

Spielman, A. J., Caruso, L. S. & Glovinsky, P. B. A behavioral perspective on insomnia treatment. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 10, 541–553 (1987).

Bastien, C. H. et al. Precipitating factors of insomnia. Behav. Sleep Med. 2, 50–62 (2004).

Swanson, L. M., Kalmbach, D. A., Raglan, G. B. & O’Brien, L. M. Perinatal insomnia and mental health: a review of recent literature. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-020-01198-5 (2020).

Lillis, T. A., Hamilton, N. A., Pressman, S. D. & Khou, C. S. The association of daytime maternal napping and exercise with nighttime sleep in first-time mothers between 3 and 6 months postpartum. Behav. Sleep Med. 16, 527–541 (2018).

Tsai, S. Y., Barnard, K. E., Lentz, M. J. & Thomas, K. A. Twenty-four hours light exposure experiences in postpartum women and their 2-10-week-old infants: an intensive within-subject design pilot study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 46, 181–188 (2009).

Hoyniak, C. P. et al. The association between maternal sleep and circadian rhythms during pregnancy and infant sleep and socioemotional outcomes. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-024-02571-y (2024).

Ciciolla, L., Addante, S., Quigley, A., Erato, G. & Fields, K. Infant sleep and negative reactivity: The role of maternal adversity and perinatal sleep. Infant Behav. Dev. 66, 101664 (2022).

Brown, S. M., Donovan, C. M. & Williamson, A. A. Maternal sleep quality and executive function are associated with perceptions of infant sleep. Behav. Sleep Med. 22, 697–708 (2024).

Kalmbach, D. A. et al. Mother-to-infant bonding is associated with maternal insomnia, snoring, cognitive arousal, and infant sleep problems and colic. Behav. Sleep Med. 20, 393–409 (2022).

Tikotzky, L. et al. Infant sleep development from 3 to 6 months postpartum: Links with maternal sleep and paternal involvement. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1, 107–124 (2015).

Sharkey, K. M., Iko, I. N., Machan, J. T., Thompson-Westra, J. & Pearlstein, T. B. Infant sleep and feeding patterns are associated with maternal sleep, stress, and depressed mood in women with a history of major depressive disorder (MDD). Arch. Womens Ment. Health 19, 209–218 (2016).

Okun, M. L., Aylward, B. S. & Phillips, E. M. Dynamic associations among infant sleep duration, maternal sleep quality and postpartum mood symptoms. J. Sleep Res. e70057 (2025).

Nakahara, K. et al. Association of maternal sleep before and during pregnancy with preterm birth and early infant sleep and temperament. Sci. Rep. 10, 11084 (2020).

Tikotzky, L., Chambers, A. S., Gaylor, E. & Manber, R. Maternal sleep and depressive symptoms: links with infant negative affectivity. Infant Behav. Dev. 33, 605–612 (2010).

Goyal, D., Gay, C. & Lee, K. Fragmented maternal sleep is more strongly correlated with depressive symptoms than infant temperament at three months postpartum. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 12, 229–237 (2009).

Cox, R.C. & Okun, M.L (in press). Postpartum maternal sleep disruption is associated with perception of infant temperament: Findings from a 6-month longitudinal study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health.

Adler, I., Weidner, K., Eberhard-Gran, M. & Garthus-Niegel, S. The impact of maternal symptoms of perinatal insomnia on social-emotional child development: a population-based, 2-year follow-up study. Behav. Sleep Med. 19, 303–317 (2021).

Pires, G. N. et al. Effects of sleep modulation during pregnancy in the mother and offspring: evidences from preclinical research. J. Sleep Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13135 (2021).

Hoyniak, C. P. et al. Sleep and circadian rhythms during pregnancy, social disadvantage, and alterations in brain development in neonates. Dev. Sci. 27, e13456 (2024).

Bai, L., Whitesell, C. J. & Teti, D. M. Maternal sleep patterns and parenting quality during infants’ first 6 months. J. Fam. Psychology https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000608 (2019).

van Straten, A. et al. Cognitive and behavioral therapies in the treatment of insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 38, 3–16 (2018).

Feng, S., Dai, B., Li, H., Fu, H. & Zhou, Y. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in the perinatal period: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep. Biol. Rhythms 22, 207–215 (2024).

Cox, R. C. & Olatunji, B. O. Concurrent and prospective links between sleep disturbance and repetitive negative thinking: specificity and effects of cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia. J. Behav. Cogn. Ther. 32, 57–66 (2022).

Belleville, G., Cousineau, H., Levrier, K. & St-Pierre-Delorme, M. E. Meta-analytic review of the impact of cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia on concomitant anxiety. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31, 638–652 (2011).

Felder, J. N., Epel, E. S., Neuhaus, J., Krystal, A. D. & Prather, A. A. Efficacy of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of insomnia symptoms among pregnant women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 77, 484–492 (2020).

Tomfohr-Madsen, L. M., Clayborne, Z. M., Rouleau, C. R. & Campbell, T. S. Sleeping for two: an open-pilot study of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in pregnancy. Behav. Sleep Med. 15, 377–393 (2017).

Kalmbach, D. A. et al. Examining patient feedback and the role of cognitive arousal in treatment non-response to digital cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia during pregnancy. Behav. Sleep Med. 20, 143–163 (2022).

Quin, N. et al. Preventing postpartum insomnia: findings from a three-arm randomized-controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, a responsive bassinet, and sleep hygiene. Sleep 47, 1–13 (2024).

Verma, S. et al. Treating postpartum insomnia: a three arm randomised controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy and light dark therapy. Psychol Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291722002616 (2022).

Bei, B. et al. Improving perinatal sleep via a scalable cognitive behavioural intervention: findings from a randomised controlled trial from pregnancy to 2 years postpartum. Psychol. Med. 53, 513–523 (2023).

Terman, M. & Terman, J. S. Light therapy for seasonal and nonseasonal depression: efficacy. Protocol, safety, and side effects. CNS Spectr. 10, 647–663 (2005).

Du, L. et al. Efficacy of bright light therapy improves outcomes of perinatal depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychiatry Res. 344, 116303 (2025).

Ricketts, E. J. et al. Morning light therapy in adults with Tourette’s disorder. J. Neurol. 269, 399–410 (2022).

Zalta, A. K., Bravo, K., Valdespino-Hayden, Z., Pollack, M. H. & Burgess, H. J. A placebo-controlled pilot study of a wearable morning bright light treatment for probable PTSD. Depress Anxiety 36, 617–624 (2019).

Sedov, I. D., Goodman, S. H. & Tomfohr-Madsen, L. M. Insomnia treatment preferences during pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 46, e95–e104 (2017).

Goodman, J. H. Women’s attitudes, preferences, and perceived barriers to treatment for perinatal depression. Birth 36, 60–69 (2009).

Maguire, P. N., Clark, G. I., Cosh, S. M. & Wootton, B. M. Exploring experiences, barriers and treatment preferences for self-reported perinatal anxiety in Australian women: a qualitative study. Aust. Psychol. 59, 46–59 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This manuscript is the result of funding in whole or in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (NIMHK23 MH137376). It is subject to the NIH Public Access Policy. Through acceptance of this federal funding, NIH has been given a right to make this manuscript publicly available in PubMed Central upon the Official Date of Publication, as defined by NIH. The funder played no role in the writing of this manuscript. The author would like to thank Drs. Lauren Hartstein & Christine So for their feedback on this manuscript and Alyssa Week and Kaitlyn Butler for their contributions to figures and tables.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.C.C. completed the literature review and wrote the manuscript text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cox, R.C. Associations between sleep and circadian rhythm disruption and perinatal anxiety. npj Biol Timing Sleep 2, 33 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44323-025-00051-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44323-025-00051-3