Abstract

Understanding how people visually engage with public transport cabins is essential for designing environments that encourage sustainable mobility. This study used eye-tracking to examine visual attention across six cabin designs: current, poorly maintained, enhanced, biophilic, cyclist-friendly, and productivity-focused. A total of 304 participants viewed each design while their eye movements were recorded, including fixation counts, time to first fixation, first fixation duration, stationary gaze entropy, and gaze transition entropy. Compared to the current version, alternative designs showed shorter TFFs and lower entropy, indicating faster orientation and more focused gaze patterns. Cabins with natural elements or functional layouts increased engagement, while poorly maintained designs led to scattered gaze. Ethnicity significantly affected FFD, with non-White participants showing shorter fixations in certain environments. Transportation habits also influenced visual attention: infrequent riders oriented more quickly in improved designs. These results highlight how design can improve user experience and support broader transit adoption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Public transportation is an integral component of urban infrastructure, facilitating the mobility of millions of people daily and contributing to economic growth and environmental sustainability1,2,3. As cities around the world face challenges such as traffic congestion, pollution, and the need for efficient and sustainable resource utilization, the role of trains, buses, and other public transit systems becomes increasingly vital. Enhancing public transportation to support sustainability moves beyond operational efficiency and environmental benefits to focus on creating systems that are inclusive, adaptive, and appealing to diverse user needs4,5. An important aspect of such systems is the overall user experience. Enhancing the user experience within these systems is paramount not only for maintaining current ridership but also for encouraging a shift away from private vehicle use, thus reducing urban carbon footprints6,7,8. Previous research shows that the physical environment of public transport cabins significantly influences passengers’ comfort, perception of safety, and overall willingness to use these services regularly9,10,11. Thus, there is a growing need to rethink and redesign these spaces to create more welcoming, functional, and user-centered environments12,13,14.

Redesigning public transportation cabins involves more than just esthetic enhancements; it requires a comprehensive understanding of how different design elements affect the passenger experience13,15. Similar to any other built environments16, one major aspect of this relationship is understanding how passengers visually interact with different cabin designs and how demographic factors influence these interactions. Traditional methods of assessing passenger experience often rely on surveys and self-reported measures, which can be subject to biases and may not capture the nuances of real-time user engagement17,18,19,20. To address this gap, there is growing interest in using objective metrics such as eye-tracking technology for measuring visual attention and cognitive processing in response to environmental variations in public transportation environments.

Eye-tracking offers a unique window into passengers’ unconscious preferences and attentional priorities by recording where, when, and how long individuals look at specific elements within a cabin space16,21,22. Metrics such as fixation duration, fixation locations and entropy measures provide quantifiable data on visual engagement, which can inform designers about which features attract attention and how users visually navigate the environment16,21,22. Understanding how various groups of users from different demographics (e.g., ethnicity, gender, public transportation use) interact with the new designs can result in efficient and more human-centric design choices, which will ultimately lead to an increase in public transportation use.

In this study, we aim to explore the intersection of public transportation cabin design, visual attention, and demographic differences by employing eye-tracking technology alongside regular survey techniques. We presented participants with six distinct cabin interior designs: Current Version, Poorly Maintained Current Version, Enhanced Version, Biophilic Design, Bike-Centered Design, and Productivity-Focused Design. These designs represent a spectrum of existing and potential future cabin configurations, each with unique features intended to address specific passenger needs and preferences.

Our objectives are threefold: first, to determine whether different cabin designs elicit varying patterns of visual attention among passengers; second, to assess how demographic factors such as frequency of public transport use, purpose of trip, and duration of use influence these patterns; and third, to provide actionable insights that can guide the development of more effective and user-friendly public transportation cabin designs. By integrating eye-tracking metrics with demographic analysis, this research contributes to a more nuanced understanding of passenger experience in public transit environments. By shedding light on how passengers of diverse backgrounds visually perceive and interact with various cabin environments, this study aims to support the creation of public transportation spaces that are not only efficient but also engaging and responsive to the needs of all users. This information is crucial for transportation authorities, designers, and policymakers seeking to enhance the appeal and functionality of public transit systems.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. We first provide a background on eye-tracking methodologies and their relevance to environmental design and public transportation research. We next detail our methodology, including participant recruitment, experimental procedures, and the specific eye-tracking metrics employed. The following section presents the results of our analysis, highlighting significant findings related to fixation counts, time to first fixation, fixation durations, and entropy measures across different cabin designs and demographic groups. We then discuss the implications of our findings, addressing how they inform design considerations and the potential limitations of our study. Finally, we conclude with recommendations for future research directions in the field of public transportation design.

This study posits that various internal and external factors significantly influence passengers’ visual engagement and overall unconscious experience. More specifically, we hypothesize that public transportation cabin designs affect visual attention metrics, including Time to First Fixation (TFF), Fixation Counts, and Gaze Entropy. Additionally, we propose that within each specific cabin, demographic factors (e.g., ethnicity, gender, frequency of public transport use, and trip purpose), as well as participants’ prior internal state (e.g., stress and emotion), influence visual attention metrics.

Literature review

User experience and the built environment

User experience in public transportation is a multifaceted construct, encompassing physical comfort, perceived safety, reliability, convenience, and the emotional response elicited by the transit environment23,24,25. Consistent with prior research on the built environment26,27,28,29,30,31, user experience is impacted by both internal and external factors, as shown in Fig. 1.

Internal factors encompass demographic characteristics and user-related states, which significantly influence how individuals perceive and interact with public transportation environments31. Demographic characteristics such as age, gender, income level, and cultural background play a crucial role in shaping expectations and preferences related to public transportation32,33. Additionally, transportation-related demographics also play an internal role. For instance, infrequent or first-time users may struggle to orient themselves in unfamiliar cabin layouts, whereas experienced commuters can more easily navigate complex environments34,35. Similarly, passengers who predominantly use public transit for work-related travel may focus on efficiency and reliability, while leisure travelers may pay more attention to esthetic quality and comfort36. Understanding these diverse user profiles is essential for developing design solutions that meet the needs of a heterogeneous ridership33 and move toward human-centric public transportation systems. Tailoring cabin features and informational materials to various user segments can enhance the overall travel experience, potentially improving satisfaction and loyalty toward public transportation systems. Another aspect of internal factors includes user-related states, such as mood, fatigue, and cognitive load, which significantly influence the perception of transit environments37,38. For instance, commuters experiencing stress or fatigue prior to entering public transit may perceive the same environment as more overwhelming compared to those in a relaxed state, affecting their satisfaction and engagement with the system. Cognitive load, often heightened by complex navigation or unclear signage, can further hinder the ability to interpret and respond to environmental cues, especially for first-time users. Addressing these states through intuitive design and clear communication can reduce cognitive strain and improve overall user experience38.

On the other hand, external factors include various physical features and maintenance-related aspects that can significantly influence user experience in public transportation39. Studies show that elements such as cabin cleanliness, ergonomic seating, proper ventilation, and lighting play a critical role in shaping how users perceive the quality and comfort of transit systems23,24,40. For example, well-maintained interiors with clean surfaces and functional amenities not only create a positive impression but also enhance users’ sense of safety and reliability23,24. Additionally, the presence of esthetic features, such as greenery, artwork, or thoughtfully designed spaces, similar to other built environments41,42,43 can evoke positive emotional responses and reduce stress levels during transit13. Maintenance-related factors, such as timely repairs, graffiti removal, and consistent upkeep, reinforce trust in the system by signaling professionalism and care for passengers44. Accessibility features, such as ramps, elevators, and clear signage, are also critical external factors that affect user experience45. These features ensure that the system is inclusive and functional for all users, including those with mobility challenges or other disabilities. Moreover, the integration of noise control measures and temperature regulation within cabins can further enhance the overall experience by addressing comfort and environmental stressors46,47.

Quantifying user experience

To better understand user interaction with the transportation built environment, various methodologies have been used in the past; many of these methods are subjective and prone to biases. For instance, traditional surveys and interviews rely heavily on self-reported data, which can be influenced by memory recall errors, social desirability, or individual perceptions that may not accurately reflect real-time experiences48. These limitations highlight the need for objective, data-driven methods to gain a deeper understanding of user interactions and responses.

Among the objective approaches, eye-tracking technology has emerged as a powerful tool for analyzing user experience21,26,27,28. Eye-tracking is a well-established methodology in human factors, cognitive psychology, and human-computer interaction research, providing objective evidence of where, when, and how long individuals direct their visual attention21. By recording eye movements such as saccades, fixations, and scanning paths, researchers gain insight into cognitive processing, user preferences, and task performance in a range of contexts across engineering, psychology, and health26,28,49,50,51,52,53. In recent years, eye-tracking technology has become more accessible, with mobile and remote trackers enabling studies in more ecologically valid environments and by enhancing the reach to a wider audience27,54,55,56,57.

Within the domain of transportation research, eye-tracking has proven valuable for understanding various aspects of driver behavior26, pedestrian and cyclist behavior28,52, as well as how users interact with the built environment16,27. Extending this methodology to public transportation cabins allows researchers to understand how passengers visually navigate interior layouts, interpret signage, and identify amenities, thereby revealing opportunities to enhance comfort and usability through design interventions58.

Image selection

User needs in cabin design have been widely explored through empirical studies and surveys, revealing several key preferences. For example, numerous studies have found that participants value flexibility, comfort, and personalization, with specific emphasis on cabin noise, visibility through windows, and climate control. Younger users prefer modern and eco-friendly designs, while older groups lean toward modular layouts for better usability14,59,60,61. The cabin design concepts were selected based on surveys and experimental research highlighting evolving commuter needs in public transport. Studies consistently show that comfort—especially in seating, lighting, and spatial layout—is a top priority, with passengers willing to pay more for enhanced seating comfort, pleasant lighting, and quiet, clean environments62,63. The inclusion of biophilic design elements, such as visible plants, aligns with findings that natural esthetics contribute to psychological comfort and increase perceived ride quality and relaxation64,65. With the rise of hybrid work models and more flexible schedules, many individuals now commute to universities or workplaces less frequently but often over longer distances. Surveys show that average one-way commute times often exceed 30 min, especially in urban areas, making the commute a significant portion of the day for many workers and students66. Recent findings also indicate a substantial shift toward remote work post-pandemic, with fewer weekly commute days but longer travel distances per trip, highlighting a growing opportunity to use commute time productively67. Incorporating workspace-enabled cabin designs caters to this evolving behavior, providing an environment that supports productivity during long transit periods while enhancing commuter satisfaction and well-being. Lastly, the bike rack cabin design draws from successful multimodal transport strategies seen in California, addressing a documented need among urban commuters for seamless transitions between cycling and public transit—a feature still rare in East Coast transit systems68.

Eye-tracking data: feature extraction and analysis

To analyze eye-tracking data, several features are derived from the raw gaze data21,26,27. The first key metric is fixation points, which represent moments when the gaze remains stationary on a particular object or area. In contrast, a saccadic movement refers to the rapid shifts of the gaze between points of fixation. From fixation data, several features can be calculated, including time to first fixation (TFF), first fixation duration (FFD), the total number of fixation points, the average fixation duration, stationary gaze entropy, and gaze transition entropy21,26,28,52.

FFD and TFF provide insights into visual salience and attention21. FFD measures the duration of the initial fixation on a specific visual element, indicating its perceived importance or ease of processing. Shorter durations may suggest familiarity and the need to explore other stimuli69 or immediate recognition. TFF measures the time it takes for the gaze to reach a specific visual element after it is presented, highlighting the prominence and salience of the element.

In addition to linear metrics, this study employs two entropy-based eye-tracking metrics, stationary gaze entropy (SGE) and gaze transition entropy (GTE), to comprehensively assess visual engagement and attention patterns within various public transportation cabin designs21,26,28. SGE quantifies the randomness in the spatial distribution of fixations across different cabin elements, while GTE measures the unpredictability of gaze transitions between these elements. Together, these metrics provide deeper insights into participants’ visual exploration strategies and the intensity of their attention. This dual assessment enables the identification of whether passengers engage with the cabin environment in a deliberate and concentrated manner or adopt a more random and exploratory approach, thereby informing design modifications that enhance passenger experience by promoting desired visual engagement behaviors.

More specifically, SGE quantifies the unpredictability in the spatial distribution of a participant’s fixations across predefined areas of interest (AOIs) within a visual field. It serves as an indicator of how dispersed or concentrated a participant’s visual attention is during the observation of complex environments. Mathematically, let \({\mathcal{A}}=\{{A}_{1},{A}_{2},\ldots ,{A}_{n}\}\) represent a set of n non-overlapping AOIs within the cabin design. During a viewing session, let fi denote the number of fixations made within AOI Ai. The probability pi of a fixation occurring in AOI Ai is calculated using Eq. (1), where \(F=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{j = 1}^{n}{f}_{j}\) is the total number of fixations across all AOIs.

The stationary gaze entropy (SGE) is then defined using Shannon’s entropy formula as shown in Eq. (2).

A high SGE value indicates a broad and uniform distribution of fixations across multiple AOIs, reflecting exploratory viewing behavior and a wide spread of attention. Conversely, a low SGE value suggests that fixations are concentrated in a few AOIs, indicating focused and deliberate attention towards specific visual elements21.

On the other hand, GTE measures the unpredictability of transitions between different AOIs during a viewing session. It captures the complexity and randomness in the sequence of visual attention shifts, thereby reflecting whether gaze movements follow a systematic pattern or are random and exploratory. Consider the same set of AOIs \({\mathcal{A}}=\{{A}_{1},{A}_{2},\ldots ,{A}_{n}\}\). Let Tij denote the probability of transitioning from AOI Ai to AOI Aj. This transition probability is estimated as described in Eq. (3), where tij represents the number of observed transitions from AOI Ai to AOI Aj.

Gaze transition entropy (GTE) is then defined as the conditional entropy of the next fixation given the current fixation using the formula presented in Eq. (4), where pi is the stationary probability of AOI Ai, calculated as shown in Equation (5).

A high GTE value implies a high level of unpredictability and randomness in gaze transitions between AOIs, indicative of exploratory and less structured viewing behavior. In contrast, a low GTE value suggests predictable and systematic transitions between AOIs, reflecting focused and goal-directed visual attention26.

Methods

This section outlines the methodological framework of the study, describing the within-subjects design and experimental setup, the recruitment process and participant characteristics, the analysis of eye-tracking metrics and areas of interest, and the development of linear mixed-effects models to examine relationships between demographic variables, cabin designs, and visual attention patterns. A schematic view of the methodology can be viewed in Fig. 2. The data for this study were gathered through a previous experimental framework performed by Hakiminejad et al.13. Below, we provide a summary of the key information required for the subsequent analysis.

This study employs a within-subjects experimental design to investigate how demographic differences influence participants’ perceptions of various public transportation cabin designs, as assessed through eye-tracking data. By utilizing a within-subjects approach, the study controls for individual differences in visual attention, ensuring that observed effects can be more confidently attributed to the design variations of the public transportation cabins.

Prior to the experiment, participants completed a Qualtrics survey designed to assess their baseline emotional and cognitive states, including momentary stress, valence (emotional positivity/negativity), and arousal (level of emotional alertness)70,71. These measures serve as the internal state prior to the experiment. More specifically, each participant responded to a one-item questionnaire for each metric of internal state13. Subsequently, they were redirected to RealEye.com72.

RealEye has been employed in numerous studies for capturing remote eye-tracking data effectively27,54,55,72. This platform utilizes an innovative webcam-based eye-tracking method that predicts a user’s gaze point by leveraging the computing power of the host computer to run a deep neural network analyzing images resulting from the computer webcam. This AI-driven process detects the participant’s face and pupils, predicting gaze points in real time. RealEye has demonstrated an accuracy of ~124 pixels on desktop and laptop devices and around 60 pixels on mobile devices, allowing for precise analysis of user interactions down to the size of a single button. Additionally, gaze points are predicted at frequencies of up to 60 Hz, facilitating detailed temporal analysis of user behavior72.

Within the platform, participants were first guided through a calibration process to ensure accurate eye-tracking data collection. The participants then viewed six distinct images representing different public transportation cabin designs, presented in a randomized order to minimize order effects: Current Version, Poorly Maintained Current Version, Enhanced Version, Biophilic Design, Bike-Centered Design, and Productivity-Focused Design. Each image was displayed for a fixed duration of 10 seconds, during which participants’ eye movements were continuously recorded through their webcam, and by employing computer vision techniques performed by RealEye.

The Enhanced Version was initially generated using DALL.E (GPT-4) with prompts carefully designed to preserve the original interior details while enhancing seating comfort, materials, and overall esthetics. Following this, no additional artificial intelligence (AI) tools were used; the remaining cabin designs were created by the authors using advanced Photoshop and rendering techniques. This approach ensured visual consistency across all designs while faithfully maintaining the conceptual and design criteria for each scenario, as shown in Fig. 3.

The figure presents six distinct cabin configurations used in the study, each with a designated AOI boundary: a Current Version, b Poorly Maintained Current Version, c Bike-Centered Design, d Biophilic Design, e Enhanced Version, and f Productivity-Focused Design. The image used for the Current Version was kindly provided by Brian Solomon86.

To ensure that the designs stayed consistent, the main stimuli were placed on the left side of the images where applicable (Fig. 3). Each cabin design was characterized by specific features intended to (1) address different passenger needs and preferences, as well as (2) simulate cabin characteristics that can affect users, such as lack of maintenance. The Current Version depicted the standard, existing design with traditional seating arrangements and basic amenities retrieved from a Northeastern regional train13. The Poorly Maintained Current Version illustrated the same design in a state of disrepair, featuring worn-out seats, inadequate lighting, and cluttered spaces. The Enhanced Version showcased improvements such as upgraded materials, ergonomic seating, advanced lighting systems, and streamlined signage. The Biophilic Design integrated natural elements, including plants and natural light simulations, to create a more calming and esthetically pleasing environment. The Bike-Centered Design included dedicated bike storage areas, while the Productivity-Focused Design incorporated work-friendly amenities such as USB charging ports, foldable tables, and partitions for semi-private workspaces.

While variations in lighting, seat shape, and overall layout were inherent to the visual stimuli, we maintained material consistency as much as possible across all designs. In our statistical models, the Current Version cabin was used as the reference category for all comparisons. However, in terms of experimental intent, the Enhanced Version was conceptually positioned as the control design for evaluating the impact of the more novel environments (i.e., Bike-Centered, Biophilic, and Productivity-Focused). This distinction allowed us to interpret model estimates relative to a common baseline while also considering design logic in the structuring of comparisons.

After viewing each image, participants answered questions regarding their willingness to use the depicted design and provided feedback on other metrics related to the environment. Upon completing the eye-tracking session, participants were directed back to Qualtrics to complete a second survey, which included a comprehensive demographic questionnaire. This questionnaire collected data on age, gender, education level, frequency of public transport use, trip purpose, duration of use, personality, psychological well-being, housing condition, and ZIP code of housing location.

The study was approved by the Villanova University Institutional Review Board (IRB; Approval Number: IRB-FY2024-92). A total of 304 participants from the Northeastern region of the United States were recruited through the Prolific Platform73 as shown in Fig. 4. Each participant received $5.20 as compensation for their 15-minute participation in the study. The demographics of all the participants in the study are shown in Table 1.

Eye-tracking data were analyzed to extract gaze metrics for each participant across cabin conditions. The RealEye platform provided fixation point locations, durations, and a data quality grade (ranging from 1 to 6) based on participants’ camera and background conditions. Participants with a quality grade below 3 were excluded due to poor tracking conditions, such as low lighting, unstable camera positioning, or excessive movement, resulting in a final sample of 273 participants. These exclusions were based on technical limitations of the online eye-tracking setup and not due to identifiable participant-related characteristics. The demographics of the included participants are shown in Table 2.

From the fixation data, the following key metrics were computed per participant and per condition, focusing on both area of interest-specific and image-specific features:

-

1.

Fixation count: Total number of fixations within the AOI.

-

2.

Time to first fixation (TFF): Time elapsed before the participant’s first fixation on the AOI.

-

3.

First fixation duration (FFD): Duration of the participant’s first fixation within the AOI.

-

4.

Stationary gaze entropy (SGE): Degree of dispersion in gaze distribution across the image, indicating how uniformly attention was allocated.

-

5.

Gaze transition entropy (GTE): Randomness of gaze transitions between AOIs, reflecting the predictability of visual scanning patterns.

To compute gaze-based entropy metrics, we employed a grid-based AOI framework that uniformly divided each image into a 10 × 10 matrix of spatial segments. Each segment represented an equal proportion of the screen area (i.e., 1% per cell), providing a consistent and standardized spatial reference across all experimental conditions. This approach ensured that gaze distributions and transitions were analyzed relative to fixed, non-semantic spatial units rather than predefined objects or regions (e.g., “window” or “seat”). Such spatial AOIs enabled robust comparisons of gaze behavior between different cabin designs while avoiding interpretive bias that can arise from subjectively defined semantic zones.

To analyze the relationship between eye-tracking metrics and participants’ demographics, we employed a combination of linear and linear mixed-effects models where applicable, using the lme4 package in the R programming language as follows. Linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) are particularly well-suited for capturing individual variability by incorporating both fixed effects (e.g., cabin design) and random effects (e.g., participant-specific differences)74,75. This capability makes LMMs especially effective for analyzing hierarchical or repeated-measures data, such as eye-tracking metrics influenced by demographic factors and cabin design. By accounting for within-participant variability, this approach allows us to examine how various designs interact with eye-tracking metrics. In the context of our study, the linear mixed-effects model can be expressed as shown in Equation (6), where:

-

yij represents the dependent variable, which corresponds to the eye-tracking metrics used in this study (e.g., gaze transition entropy, time to first fixation, and stationary gaze entropy).

-

β0 is the fixed intercept, indicating the baseline value of the dependent variable.

-

β1 represents the fixed effects of gender and ethnicity.

-

β2 represents the fixed effects of the cabin design images (e.g., bike-centered design, biophilic design).

-

(Demographics)ij denotes the gender and ethnicity variables for the jth participant in the ith group.

-

(Cabin Design)ij denotes the specific cabin design image viewed by the jth participant.

-

b0i is the random intercept, accounting for variability between participants (e.g., individual differences in baseline perceptions).

-

ϵij is the residual error term, assumed to follow a normal distribution (ϵij ~ N(0, σ2)).

This model evaluates how demographic characteristics and the specific cabin design images influence participants’ perceptions, as measured through eye-tracking metrics. By including both fixed and random effects, the model captures individual variability while examining the broader effects of demographics and cabin designs on participant perceptions. In addition to the mixed-effects models, we conducted a series of linear regression analyses for each cabin image separately to evaluate how participants’ eye-tracking responses (e.g., fixation duration, gaze entropy) varied as a function of their transportation-related demographics (e.g., frequency of public transport use, purpose of trip, duration of use) while controlling for gender and ethnicity. These cabin-specific models allowed us to explore within-design effects and better understand how individual characteristics shaped visual engagement with each environment. All cabin designs were modeled relative to the Current Version baseline to assess their individual effects on eye-tracking metrics. Our primary interest was in evaluating how each alternative design deviated from the existing public transportation interior rather than conducting pairwise comparisons across all conditions.

Results

To present our findings in a structured and coherent manner, we begin by analyzing the specific locations where participants directed their attention across the various cabin designs. This is followed by a comparative analysis of cabin perceptions based exclusively on eye-tracking metrics. Finally, the results explore how demographic variables relate to eye-tracking measures associated with these cabin perceptions. To support clear interpretation of the findings, the Results section is structured to first present outcomes that show statistically significant differences, followed by a summary of results that were not significant. This approach highlights the main effects observed across eye-tracking measures and demographic factors, while still providing a complete overview of all analyses. Significant results (p < 0.05) are described in detail within the main section, and non-significant findings are grouped at the end of the section to maintain focus and readability.

The heatmaps presented in Fig. 5 illustrate participants’ fixation patterns across six distinct cabin designs, offering insights into areas of heightened visual attention. The red regions in the heatmaps represent high fixation density, indicating where participants focused their gaze most frequently. In the Current Version (Fig. 5a), participants predominantly fixated on the seats located in the middle of the cabin—likely due to the design’s uniformity and straightforward layout. By contrast, the Poorly Maintained Current Version (Fig. 5b) exhibits more dispersed attention, particularly drawn to obvious signs of wear and tear, scuff marks, and general clutter. These indicators of neglect appear to act as strong visual stimuli, highlighting how the lack of maintenance can significantly influence where viewers direct their gaze. The Bike-Centered Design (Fig. 5c) significantly redirected participants’ attention to the bicycle area, with the highest fixation density concentrated on the bikes themselves. This finding underscores the bike’s salience as a focal stimulus, demonstrating the design’s effectiveness in capturing visual attention.

In the Biophilic Design (Fig. 5d), participants’ gaze was drawn towards both the seating area and greenery elements. The presence of plants introduced an additional visual anchor, balancing attention between functional (seating) and esthetic (plants) components. Meanwhile, the Enhanced Version (Fig. 5e) revealed a similar concentration of fixations on seating, with a subtle shift towards the central aisle. This pattern suggests that the streamlined layout of the enhanced cabin promoted a more evenly distributed gaze, reducing visual clutter and fostering a structured viewing experience. Finally, in the Productivity-Focused Design (Fig. 5f), participants’ attention shifted towards the workstations on the right side of the cabin. By integrating functional elements such as desks and chairs, the design successfully drew participants’ gaze away from the standard seating areas and toward the workspace, emphasizing productivity-related features.

Time to first fixation was a key outcome of the study (as shown in Fig. 6), which was compared across the different cabin designs using a linear mixed-effects model. The results indicate that all tested designs elicited statistically significant reductions in TFF when compared to the baseline intercept (Current Version). As shown in Table 3, among the designs, the Biophilic design demonstrated the largest negative effect (−1443.00 ms, p < 2 × 10−16). Similarly, the Poorly Maintained Current Version, Bike, Productivity, and Enhanced Version designs also exhibited large and statistically significant reductions in TFF (p < 2 × 10−16 for all). These findings suggest that participants oriented their gaze more rapidly to each of these alternative designs than to the baseline, drawing their attention.

Stationary gaze entropy was also analyzed across the different cabin designs using a linear mixed-effects model, with the distribution presented in Fig. 7. The results, presented in Table 4, indicate that several tested designs elicited significant deviations in SGE relative to the baseline intercept (Current Version). Among the designs, the Bike configuration exhibited the largest negative effect (−0.191, p < 2 × 10−16), reflecting a substantial reduction in gaze dispersion. Similarly, the Biophilic Design (−0.124, p < 2 × 10−16), Productivity (−0.067, p < 2 × 10−16), and Enhanced Version (−0.168, p < 2 × 10−16) conditions all demonstrated significant decreases in SGE, suggesting more focused and predictable gaze behavior. In contrast, the Poorly Maintained Current Version elicited a slight but significant increase in SGE (0.012, p = 0.00705), indicating a more dispersed gaze pattern compared to the baseline. These findings suggest that certain cabin designs may promote more concentrated visual engagement, while others lead to more scattered gaze patterns.

Gaze transition entropy was also compared across the different cabin designs using a linear mixed-effects model. The overall distribution of GTE across designs is presented in Fig. 8. As shown in Table 5, the intercept (4.781) represents the baseline GTE for participants in the reference condition (Current Version), indicating a relatively high degree of randomness in gaze transitions under this condition. Among the designs, the Enhanced Version demonstrated the largest negative effect (−0.056, p < 2 × 10−16), reflecting a substantial decrease in gaze transition randomness. Similarly, the Bike (−0.053, p < 2 × 10−16), Biophilic Design (−0.025, p < 2 × 10−16), and Productivity (−0.008, p = 0.00483) conditions also exhibited significant reductions in GTE, suggesting more structured and predictable gaze transitions. In contrast, the Poorly Maintained Current Version elicited a slight but significant increase in GTE (0.017, p = 5.61 × 10−10), indicating a more scattered gaze pattern compared to the baseline. These findings imply that designs featuring more intentional, streamlined visual elements may promote focused and predictable gaze behavior, while environments with higher visual complexity or clutter may encourage more dispersed and less directed gaze transitions.

In the following section, we present the results of analyses examining the relationship between key demographic variables (i.e., frequency of public transportation use, duration of use, and purpose of trip) and selected eye-tracking metrics (i.e., FFD, TFF, SGE, and GTE). To aid clarity, results are organized by cabin design. For brevity, we report only those cabin designs that showed statistically significant effects on the respective eye-tracking metrics. Results that did not reach statistical significance are summarized later in a dedicated subsection.

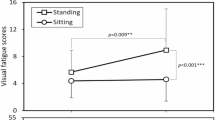

For frequency of public transport use, we grouped responses into two broader categories: Most of the Time, which combined the original responses of Always, and Most of the Time, and About Half of the Time and Less, which included the responses of About Half of the Time, Sometimes, and Never. This section focuses exclusively on the First Fixation Duration metric from the eye-tracking data, as other measures did not yield significant results in our modeling efforts. The distribution of FFD by frequency of public transport use across cabin designs is shown in Fig. 9. Overall, the regression analyses revealed that public transport use frequency did not significantly affect FFD in the Current Version, Enhanced, and Bike-Centered cabin designs. However, in the Poorly Maintained and Biophilic designs, participants who used public transport about half of the time or less exhibited significantly shorter FFDs compared to more frequent users. Additionally, in the Productivity cabin design, ethnicity emerged as a significant predictor of FFD, indicating that demographic factors may influence visual engagement in certain environments. The details of the analysis are provided below.

In the Poorly Maintained Current Version condition, regression analysis revealed a statistically significant association between public transport use frequency and FFD, as shown in Table 6. Participants who reported using public transport about half of the time or less exhibited a 46.96 ms decrease in FFD (p = 0.014), suggesting that they directed their gaze more rapidly than those who use public transport more frequently. Additionally, identifying as non-White was associated with a 34.36 ms reduction in FFD (p = 0.032).

In the Biophilic cabin design, regression analysis revealed a statistically significant effect of public transport use frequency on FFD, as shown in Table 7. Participants who used public transport about half of the time or less exhibited a 53.39 ms reduction in FFD (p = 0.00218), suggesting that they oriented their gaze more rapidly than those who use public transport more frequently. This finding may indicate that less frequent users are more sensitive to the biophilic elements or find them more novel, resulting in quicker initial engagement.

In the Productivity cabin design, regression analysis did not reveal a statistically significant effect of public transport use frequency on FFD, as shown in Table 8. Participants who reported using public transport about half of the time or less had an FFD that was shorter by 26.77 ms, but this difference was not significant (p = 0.139). In contrast, identifying as non-white was associated with a 29.92 ms reduction in FFD, which reached statistical significance (p = 0.049). These results highlight that demographic factors may play a role in visual engagement.

For the purpose of the trip variable, we focus exclusively on the time to first fixation metric from the eye-tracking data (as shown in Fig. 10), as other measures did not yield significant results in our modeling efforts for any of the cabin designs when considering the effect of demographic variables. Overall, the regression analyses indicated that the purpose of the trip did not significantly affect TFF in the Current Version, Poorly Maintained, Biophilic, Bike-Centered, and Productivity cabin designs. However, in the Enhanced cabin design, both commuting to work and leisure travel purposes were significantly associated with shorter TFFs compared to other usage patterns. Additionally, in the Biophilic cabin design, ethnicity emerged as a significant predictor of TFF, suggesting that demographic factors may influence visual engagement in specific environments.

In the Enhanced cabin design, regression analysis revealed a significant association between the purpose of public transport use and TFF, as shown in Table 9. Participants who commute to work (−139.20 ms, p = 0.0203) or use public transport for leisure (−140.77 ms, p = 0.0154) exhibited significantly shorter TFFs compared to those with other usage patterns. These results suggest that travel purpose may influence how quickly individuals orient their gaze in a more visually streamlined environment.

A comparison of Fixation Counts in the areas of interest between the images was carried out using linear mixed-effect model. The variation in fixation counts among cabin designs is depicted in Fig. 11. As shown in Table 10, results indicate that none of the tested designs elicited statistically significant differences in fixation counts when compared to the baseline intercept (Current Version). Among the designs, the Enhanced Version demonstrated the largest negative effect (−0.33333) and exhibited borderline significance (p = 0.0926). However, this did not meet the standard threshold for statistical significance (p < 0.05). Similarly, other designs, including Poorly Maintained Current Version, Bike, Productivity, and Biophilic Design, exhibited minor positive or negative effects, but none achieved statistical significance. These findings may suggest that participants did not exhibit substantial differentiation among the designs in terms of their fixation counts, although the possibility of differences cannot be ruled out, potentially due to limited sample size or variability in the data.

A comparison of First Fixation Duration among the different cabin designs was carried out using a linear mixed-effects model. Fig. 12 provides a visual summary of first fixation duration distributions across the different cabin designs. The results indicate that none of the tested designs elicited statistically significant differences in FFD, as shown in Table 11, when compared to the baseline intercept (Current Version). Among the designs, the Biophilic Design demonstrated the largest positive effect (16.414 ms) and approached significance (p = 0.0544), though it did not meet the conventional threshold for statistical significance (p < 0.05). Similarly, other designs, including Poorly Maintained Current Version, Bike, Productivity, and Enhanced Version, exhibited minor positive or negative effects, but none achieved statistical significance. These findings suggest that participants did not substantially differentiate among the designs in terms of their initial fixation durations, although the possibility of differences cannot be ruled out, potentially due to limited sample size or variability in the data.

While several cabin designs revealed significant associations between Demographic Variables and eye-tracking metrics, other conditions showed no statistically significant effects of factors such as the frequency or duration of public transportation use, or trip purpose, on First Fixation Duration. In this subsection, we summarize the results from cabin designs where these demographic variables did not significantly influence eye-tracking measures. Although these findings did not meet conventional significance thresholds (p > 0.05), they are reported here for completeness and to provide a comprehensive view of the data patterns across all experimental conditions.

In the Current Version condition, a linear regression model was used to examine the effect of public transport use frequency on FFD while also controlling for gender and ethnicity. As shown in Table 12, none of the included variables produced statistically significant effects on FFD. Specifically, participants who used public transport “About Half of the Time and Less” displayed no significant difference in FFD compared to those who used it “Most of the Time” (Estimate = −2.720, p = 0.885). Similarly, identifying as non-Male (Estimate = 1.228, p = 0.932) or non-White (Estimate = −13.139, p = 0.406) was not associated with any significant variation in FFD relative to the baseline categories. These findings should be interpreted with caution, as the lack of significant effects may stem from methodological constraints such as limited sample size or insufficient variability.

In the Bike-Centered cabin design, regression analysis did not reveal a statistically significant effect of public transport use frequency on FFD, as shown in Table 13. Although the estimate for participants who use public transport about half of the time or less was negative (−20.69 ms), this difference did not reach conventional levels of significance (p = 0.243).

In the Enhanced Version cabin design, regression results shown in Table 14 indicate that, similar to the Bike-Centered condition, public transport use frequency did not have a statistically significant effect on FFD. Although participants who used public transport about half of the time or less showed a slightly shorter FFD (−11.672 ms), this difference was not significant (p = 0.520).

The effect of Public Transport Use Purpose on Time to First Fixation was also examined in the Current Version environment using linear regression analysis. As shown in Table 15, the analysis did not reveal any statistically significant relationships. Neither commuting to work (Estimate = 52.50 ms, p = 0.9483) nor leisure travel (Estimate = −37.17 ms, p = 0.9626) significantly influenced TFF.

In the Poorly Maintained Current Version environment, linear regression analysis did not reveal any statistically significant effects of public transport use purpose on Time to First Fixation, as shown in Table 16. Neither commuting to work (Estimate = −2.692 ms, p = 0.937) nor leisure use (Estimate = −26.442 ms, p = 0.421) was associated with a statistically significant change in TFF.

In the Biophilic cabin design, regression analysis did not yield any statistically significant effects of public transport use purpose on Time to First Fixation, as shown in Table 17. Neither commuting to work (Estimate = 13.808 ms, p = 0.604) nor leisure travel (Estimate = 7.022 ms, p = 0.785) showed a meaningful impact on TFF. Although identifying as non-White was associated with a significant increase in TFF (p < 0.001), the absence of significant effects for travel purpose should be interpreted with caution, considering potential limitations such as sample size or variability in the data.

In the Bike-Centered cabin design, regression analysis did not reveal any statistically significant relationship between the purpose of public transport use and TFF, as shown in Table 18. Neither commuting to work (Estimate = 17.234 ms, p = 0.607) nor leisure travel (Estimate = 28.888 ms, p = 0.373) significantly influenced TFF.

In the Productivity cabin design, regression analysis did not reveal any statistically significant effects of public transport use purpose on TFF, as shown in Table 19. Neither commuting to work (Estimate = −27.801 ms, p = 0.4687) nor leisure travel (Estimate = −24.051 ms, p = 0.5168) significantly influenced TFF. Although identifying as non-White was associated with a significant increase in TFF (p < 0.0002), the overall results suggest that the purpose of public transport use did not meaningfully shape participants’ initial visual engagement with this cabin.

This analysis examines the impact of public transport use duration on FFD across various cabin designs (see Fig. 13). Across all cabin designs—including Current Version, Poorly Maintained, Enhanced, Biophilic, Bike-Centered, and Productivity—the regression analyses consistently indicated no statistically significant relationships between public transport use duration and FFD. The duration categories (e.g., 15–30, 30–45, 45–60 min, “Don’t Know,” and “More than One Hour”) did not produce notable deviations in FFD compared to the reference condition (all p > 0.05). A detailed analysis of the results is provided as an “Supplementary Information”.

While the majority of results were non-significant, certain demographic variables exhibited significant effects in specific cabin designs:

-

Poorly Maintained Current Version: Identifying as non-White was associated with a statistically significant reduction in FFD (p = 0.00593).

-

Enhanced Version: Identifying as non-White remained a significant predictor, associated with a 41.66 ms reduction in FFD (p = 0.0147).

In order to access a consolidated view of the regression results across all cabin designs, refer to Table 20.

We investigated the influence of participants’ emotional states before viewing the cabin designs as a proxy for their emotional state prior entering public transportation, specifically stress, valence, and arousal on their visual engagement, as measured by Time to First Fixation, First Fixation Duration and Entropy measures across the cabin designs. The regression analyses did not reveal any statistically significant relationships between these emotional state variables and the eye-tracking metrics. These findings suggest that baseline emotional states may not substantially impact initial visual attention in the context of observing cabin environments. For a comprehensive overview of the regression results, please refer to “Supplementary Information”.

Discussion

This study advances our understanding of how passengers visually engage with public transportation cabin environments by integrating eye-tracking metrics with public transportation usage factors. While earlier research primarily relied on self-reported surveys13,76,77, our approach offers a more direct and nuanced perspective on how passengers visually navigate these spaces. By analyzing gaze behavior across groups defined by various usage patterns and demographic factors, we uncover subtle relationships that may be overlooked by self-reported measures alone. Our findings demonstrate that while certain cabin designs and demographic variables can influence the manner and speed with which participants direct their gaze, these effects are neither universal nor consistent across all measured dimensions. In the following discussion, we highlight key observations for each eye-tracking metric, consider their potential implications for improving cabin design, and examine how participant characteristics—such as frequency, purpose, and duration of public transportation use—shape visual engagement patterns.

The comparisons of fixation counts among the various cabin designs revealed no statistically significant differences relative to the baseline Current Version (Table 10). Although the Enhanced Version approached significance, the lack of a definitive effect may suggest that participants did not fundamentally vary their distribution of fixations based solely on the cabin design. One interpretation is that fixation count alone may be insufficiently sensitive to detect subtle differences in how participants visually parse a complex environment. Similar results were observed in previous studies with eye-tracking data, where fixation counts did not adequately capture nuanced attentional shifts in intricate visual settings78.

In contrast, the Time to First Fixation results presented a more pronounced pattern (Table 3) and revealed a different story. All tested designs, including Biophilic Design, Poorly Maintained Current Version, Bike, Productivity, and Enhanced Version, demonstrated significantly shorter TFFs compared to the Current Version. This pattern suggests that participants oriented their gaze more rapidly to features within these alternative configurations. In line with prior literature, one possible explanation is that these designs contain more salient or attention-grabbing elements, guiding participants’ gaze more efficiently79,80. Prior studies show that environments incorporating biophilic design elements improve participants’ perceptions of comfort and reduce stress levels41,43,81,82,83. These results were also replicated for cabin designs by increasing comfort, decreasing stress, and negative emotions13. The eye-tracking results support these findings by indicating that such designs contain highly salient features that facilitate intuitive visual engagement. For example, previous findings revealed that participants rated biophilic cabins as significantly more calming and inviting, which aligns with the shorter TFF observed here, suggesting that participants quickly focused on familiar and visually appealing elements like greenery and natural textures. Our findings demonstrate how both conscious impressions and unconscious gaze behaviors highlight the importance of design choices that foster positive user experiences.

For First Fixation Duration, no design exhibited a statistically significant difference compared to the Current Version, though the Biophilic Design approached significance (Table 11). FFD reflects the initial temporal investment of attention on the first element viewed, and the lack of significant differences implies that once participants found their initial fixation point, they did not spend substantially more or less time there across different designs. This outcome further underscores the complexity of interpreting eye-tracking metrics in isolation. The rapid orientation suggested by TFF findings does not necessarily translate into deeper attention as measured by FFD.

The entropy-based metrics, SGE and GTE, provide a more holistic measure of visual exploration patterns. The results indicated that certain cabin designs led to more structured and predictable gaze distributions (lower entropy), while others encouraged more scattered gaze patterns (higher entropy) (Tables 4 and 5). Specifically, the Bike, Biophilic Design, Productivity, and Enhanced Version designs all resulted in significantly lower SGE and GTE, suggesting that participants visually parsed these environments in a more systematic and coherent manner, which aligns with prior findings demonstrating that structured environments facilitate more efficient visual processing84. These patterns may reflect a design’s visual clarity, thematic coherence, or presence of salient features that help guide participants’ gaze. Conversely, the Poorly Maintained Current Version condition resulted in increased entropy measures, potentially indicating visual clutter or elements that distract participants from forming a stable viewing pattern. These findings imply that designs featuring more intentional, streamlined visual elements promote focused and predictable gaze behavior, enhancing the efficiency with which passengers navigate the space. Lower entropy in gaze patterns can be indicative of environments that facilitate easier information processing and reduce cognitive load, contributing to a more comfortable and user-friendly experience21. These findings collectively suggest that intentional and streamlined visual elements in cabin designs not only attract quicker attention but also facilitate more organized visual processing, enhancing the efficiency with which passengers navigate the space. Beyond cabin design, we explored how demographic variables—specifically frequency, purpose, and duration of public transportation use—relate to eye-tracking metrics. These factors offer insights into how individual differences and travel behaviors influence visual engagement with cabin environments. For the frequency of public transport use, most cabin designs did not show a significant relationship with FFD, except for a few noteworthy cases. In the Poorly Maintained Current Version and Biophilic Design conditions, participants who used public transport about half of the time or less exhibited significantly shorter FFDs compared to more frequent users (Tables 6 and 7). These findings point out that less frequent users might find certain elements more novel or striking, prompting quicker initial fixations. Alternatively, familiarity with public transport settings could influence the expectation of what to observe first, leading frequent users to scan more systematically rather than locking onto salient features immediately.

Regarding the purpose of the trip, the regression analyses indicated that the purpose of the trip did not significantly affect TFF in most cabin designs, including Current Version, Poorly Maintained, Biophilic, Bike-centered, and Productivity (Table 20). However, in the Enhanced Version cabin design, both commuting to work and leisure travel purposes were significantly associated with shorter TFFs compared to other usage patterns (Table 9). This suggests that in more visually streamlined environments, the purpose of travel can influence how quickly individuals orient their gaze, potentially reflecting different attentional strategies based on travel motivations.

The analysis of public transport use duration revealed that, overall, duration did not significantly influence FFD across most cabin designs (Table 20). However, ethnicity emerged as a significant predictor of FFD in several cabin environments. Specifically, in the Productivity cabin design, participants identifying as non-White exhibited a significant reduction in FFD (Table 8). Additionally, in both the Enhanced Version and Poorly Maintained Current Version cabin designs, non-White participants demonstrated shorter FFDs (Tables 9 and 8). These demographic differences suggest that ethnicity may influence visual attention patterns within certain cabin environments, potentially reflecting diverse visual processing strategies or varying levels of familiarity with the design elements. This finding underscores the importance of considering demographic diversity in cabin design to ensure that visual elements cater to a broad spectrum of users.

While frequency and purpose of public transport use generally did not impact FFD and TFF across all designs, significant effects emerged within specific cabin environments, suggesting that passenger characteristics may modulate how certain designs are visually processed.

These findings point to several implications for public transport cabin design that can enhance both user experience and operational efficiency. First, maintaining cleanliness and reducing clutter is essential for minimizing visual distractions. Environments that resemble the Poorly Maintained Current Version produce scattered gaze patterns and heightened mental effort as passengers attempt to navigate disordered spaces. By keeping interiors tidy, organized, and free from unnecessary signage or decorations, designers can help passengers quickly locate important features, fostering a sense of comfort and trust that may encourage continued ridership.

In addition to cleanliness, integrating natural elements and employing structured layouts can guide passenger attention more intuitively. Cabins inspired by the Biophilic Design or Enhanced Version concepts, for instance, were associated with more predictable gaze patterns and faster orientation. Incorporating greenery, uniform color schemes, and clearly delineated zones can help passengers efficiently process visual information, improving their perception of the environment’s esthetics and functionality. This streamlined visual experience not only enhances user satisfaction but may also reinforce perceptions of safety and well-being13.

Demographic considerations further inform these design strategies. Since less frequent or first-time public transport users may struggle to orient themselves, the aforementioned designs can enhance their experience. By ensuring that diverse passenger groups—from daily commuters to occasional leisure travelers—can quickly and confidently interpret the environment, transportation systems can become more inclusive and appealing. Additionally, recognizing that ethnicity can influence visual engagement patterns, designers should consider culturally diverse perspectives to create universally navigable and comfortable spaces.

Crucially, these implications need not remain static. Continuous refinement through feedback—collected via passenger surveys, focus groups, and pilot tests—can guide incremental improvements. By complementing traditional qualitative insights with objective, real-time measures obtained through eye-tracking, our methodology establishes a feedback loop that connects genuine user perceptions with tangible design adaptations. This approach allows designers to test new interventions, observe how users genuinely respond in real-world scenarios, and then refine the space accordingly. In doing so, public transport cabin environments can evolve steadily, becoming not only cleaner, more organized, and more intuitive but also finely attuned to passengers’ evolving expectations and needs. Over time, this iterative process holds the potential to make public transportation more accessible, enjoyable, and appealing to a wide range of users, ultimately advancing broader sustainability and mobility objectives.

While our findings provide valuable insights into how passengers visually engage with different public transportation cabin designs, several limitations should be noted. The study was conducted using static images rather than immersive or real-world conditions. Although eye-tracking data from these images can highlight participants’ initial visual orientation, it may not fully capture the dynamic nature of real transit environments—where movement, crowding, and ambient factors (e.g., noise, temperature) can influence attention and perception. Future research could employ virtual reality (VR) headsets or augmented reality (AR) simulations to create more ecologically valid scenarios, enabling participants to navigate and interact with virtual cabin spaces in real time.

Another limitation of this study is the use of RealEye’s AI-based gaze estimation system, for which we did not develop or have access to the underlying deep learning model, its training data, or its demographic composition. While the platform reports compatibility across diverse populations and devices, the lack of transparency in its development and validation processes raises concerns about potential demographic bias in gaze estimation accuracy. As such, systematic errors introduced by the model—particularly those affecting specific demographic groups—cannot be ruled out. Although our study focused on comparing visual attention patterns across cabin designs rather than validating the gaze model itself, we acknowledge that model bias could influence results. Future research should critically assess and report the demographic performance of gaze estimation tools to enhance the equity and interpretability of visual attention studies.

The within-subjects design, while controlling for individual differences in baseline visual behavior, could introduce familiarity effects. Although the image presentation was randomized, repeated exposure to multiple cabin designs may have led participants to become more familiar with the task and change their exploration patterns (e.g., scanning more quickly or focusing on different elements) by the final designs. Employing between-subjects designs or counterbalancing the order of stimuli across subgroups may help mitigate these potential carryover effects.

The demographic breakdown of the sample—while diverse—may not fully represent broader transit-riding populations, especially regarding age, health, and socio-economic diversity. Factors such as visual acuity, disability, cultural background, or experience with other transit systems can mediate user responses. Additionally, participants were recruited via an online platform (Prolific), which may skew toward individuals who are more technologically savvy or have reliable internet access. Future investigations could integrate on-site or lab-based data collection to sample passengers with different technology access or specific ridership profiles (e.g., older adults, individuals with visual or cognitive impairments) for more inclusive insights.

One important aspect for consideration related to demographic background is the interaction between cabin design and demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, or transit familiarity. While the current analysis focused on main effects, future work will incorporate interaction terms to explore how user characteristics may differentially influence visual attention patterns. For example, certain design features—such as biophilic elements or lighting configurations—may elicit stronger responses from particular demographic groups. Employing two-way or multi-way ANOVA in future analyses would enable us to capture these nuanced relationships and better understand for whom and under what conditions specific cabin designs are most effective. However, detecting interaction effects robustly requires adequate statistical power, which may necessitate larger and more balanced samples. Therefore, future studies will prioritize broader participant recruitment and stratified sampling strategies to enable a more comprehensive, inclusive, and scientifically robust examination of these potential moderating effects.

Additionally, the grouping of participants into broad demographic categories—such as “non-White”—may have introduced greater variability within groups, potentially affecting model assumptions such as homoscedasticity. While linear mixed-effects models are generally robust to moderate violations of this assumption, future studies may benefit from modeling heterogeneous variances or using more granular demographic groupings to capture within-group diversity more accurately.

While the remote eye-tracking approach enabled broad participation and flexible data collection, it inherently introduces variability—such as differences in monitor size, lighting conditions, or webcam quality—that may affect tracking accuracy. Although the RealEye platform includes calibration procedures and data-quality metrics, minor inaccuracies could still influence the results (e.g., drifting fixations in edge regions of the screen). Employing standardized hardware in controlled laboratory settings or using portable eye-tracking glasses for field studies can improve data precision and validate these remote findings.

Given that the eye-tracking data in this study were obtained using a deep neural network model embedded within a commercial platform (RealEye), and that we do not have access to details about the demographic composition of its training set, there remains a possibility that observed differences between demographic groups could be partially influenced by uncorrected model bias. While prior work has extensively used this platform27,54,55,72, future research should consider the validation of such AI-based gaze estimation tools across diverse populations to disentangle behavioral differences from potential algorithmic bias.

The study focused on relatively short (10-s) exposures to each cabin image. Although this duration is useful for capturing quick, initial impressions and “bottom-up” visual salience, longer viewing times might reveal deeper exploration strategies—such as searching for signage, noticing comfort features, or assessing cleanliness more thoroughly. Future work could vary exposure lengths or allow participants to freely explore 360° cabin panoramas to better simulate how actual passengers might scan a space over the course of a journey.

Metrics based on entropy, such as Shannon’s entropy (SGE) and gaze transition entropy (GTE), are widely used to analyze visual attention and engagement patterns. However, their sensitivity to the number of defined Areas of Interest (AOIs) can influence the interpretation of results. In this study, AOIs were consistently defined across all cabin design conditions, reducing variability and enhancing the comparability of entropy values. Despite this control, entropy-based measures still face limitations in their ability to reflect uniformity across different visual contexts. To improve the robustness and interpretability of such analyses, future research could consider incorporating normalized indices like Pielou’s Evenness, which accounts for differences in category count and provides a more balanced view of distribution evenness85.

It is important to note that each cabin design used in this study represented a composite of multiple design elements—such as materials, lighting, and spatial arrangements—intended to simulate realistic and varied transit environments. As such, observed differences in visual attention patterns cannot be definitively attributed to any single design feature. Future work should employ more controlled experimental conditions that systematically vary individual environmental components to isolate their specific contributions to gaze behavior. This will allow for a clearer causal interpretation of how particular features influence visual engagement.

Although multiple regression models were conducted across different cabin designs, each analysis was interpreted independently to assess within-cabin demographic effects. Therefore, no multiple comparison correction was applied across designs. Nonetheless, marginally significant results should be interpreted with caution.

One important aspect for future consideration is the inclusion of interaction terms between cabin design and demographic variables. Incorporating moderation models would allow researchers to examine whether the effect of a given cabin design on visual attention metrics differs systematically across demographic groups. This would enable more fine-grained modeling of heterogeneous user experiences. Future studies with larger sample sizes or extended datasets should consider testing such interaction effects and comparing model fit using AIC/BIC, or similar criteria.

Finally, while the entropy-based metrics (stationary gaze entropy and gaze transition entropy) offer rich insights into the structure of visual exploration, they do not directly capture emotional responses or interpret whether a gaze pattern is “positive” or “negative.” Integrating psychophysiological measures (e.g., skin conductance, heart rate variability), observational data (e.g., dwell times near certain amenities in an actual transit car), or qualitative interviews could enrich our understanding of the interplay between visual engagement, emotional reactions, and ultimate behavior (e.g., willingness to ride). Longitudinal studies, following participants over repeated encounters with newly implemented cabin features, could also ascertain whether initial attention patterns predict real shifts in satisfaction, perceived safety, and ridership.

By addressing these methodological and contextual constraints, future research can build upon our findings to develop more comprehensive and ecologically valid evaluations of public transportation environments. Doing so will not only improve cabin design strategies but also help meet broader goals of increasing transit adoption, enhancing user well-being, and promoting more sustainable mobility.

Conclusion

Our study contributes to a nuanced understanding of how cabin design influences visual attention and exploration. While the Current Version did not strongly differ from other designs in fixation counts or FFD, significant patterns in TFF and entropy-based metrics emerged, painting a more intricate picture of engagement. Designs that introduce biophilic elements, enhanced organization, or thematic coherence appear to encourage more structured and focused gaze patterns, whereas cluttered or less optimized environments foster more dispersed viewing.

Demographic variables related to public transport use also demonstrated selective influences on gaze metrics, highlighting that not all individuals engage with these environments in the same manner. Such differences may reflect varying levels of familiarity, motivation, or susceptibility to environmental cues. Although many relationships did not reach statistical significance, the trends observed encourage further exploration into the interplay between user characteristics and environmental design.

Overall, these findings emphasize the importance of employing multiple eye-tracking metrics and considering participant heterogeneity when evaluating visual engagement in complex environments. By doing so, researchers and designers can gain richer insights into how to create or modify spaces that better guide attention, improve user experience, and ultimately influence perception and behavior.

Data availability

Due to ethical considerations and privacy restrictions imposed by the Institutional Review Board, the data supporting the findings of this study cannot be shared publicly. The data include sensitive information about participant demographics and eye-tracking metrics, which are subject to confidentiality agreements to protect participant privacy. For further inquiries, please contact the corresponding author. The data can be made available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of the IRB.

Code availability

No custom code or scripts were used in the generation or analysis of the data. All analyses were performed using standard, publicly available software packages, as detailed in the Methods section.

References

Zhou, B., Jin, J., Huang, H. & Deng, Y. Exploring the macro economic and transport influencing factors of urban public transport mode share: a Bayesian structural equation model approach. Sustainability 15, 2563 (2023).

Chatman, D. G. & Noland, R. B. Do public transport improvements increase agglomeration economies? a review of literature and an agenda for research. Transp. Rev. 31, 725–742 (2011).

Nanaki, E. et al. Environmental assessment of 9 European public bus transportation systems. Sustain. Cities Soc. 28, 42–52 (2017).

Nahiduzzaman, K. M. et al. Influence of socio-cultural attributes on stigmatizing public transport in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 13, 12075 (2021).

Te Morsche, W., Puello, L. L. P. & Geurs, K. T. Potential uptake of adaptive transport services: an exploration of service attributes and attitudes. Transp. Policy 84, 1–11 (2019).

McLeod, S., Scheurer, J. & Curtis, C. Urban public transport: planning principles and emerging practice. J. Plan. Lit. 32, 223–239 (2017).

Adewumi, E. & Allopi, D. Rea Vaya: South Africa’s first bus rapid transit system. S. Afr. J. Sci. 109, 1–3 (2013).

Foth, M. & Schroeter, R. Enhancing the experience of public transport users with urban screens and mobile applications. In MindTrek '10: Proc. of the 14th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments 33–40 (2010).

Morton, C., Caulfield, B. & Anable, J. Customer perceptions of quality of service in public transport: evidence for bus transit in Scotland. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 4, 199–207 (2016).

Friman, M., Lättman, K. & Olsson, L. E. Public transport quality, safety, and perceived accessibility. Sustainability 12, 3563 (2020).

Ingvardson, J. B. & Nielsen, O. A. The influence of vicinity to stations, station characteristics and perceived safety on public transport mode choice: a case study from Copenhagen. Public Transp 14, 459–480 (2022).

Putri, N. F. et al. Ergonomic evaluation in public transport particularly in public transportation with an anthropometric approach in Tegal city: enhancing comfort and safety in urban transportation through anthropometric design adjustments. J. Sci. Res. Educ. Technol. 3, 1680–1690 (2024).

Hakiminejad, Y., Pantesco, E. & Tavakoli, A. Public transit of the future: Enhancing well-being through designing human-centered public transportation spaces.Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 30, 101365 (2025).

Stolz, M., Reimer, F., Moerland-Masic, I. & Hardie, T. A user-centered cabin design approach to investigate peoples preferences on the interior design of future air taxis. In 2021 IEEE/AIAA 40th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), San Antonio, TX, USA (IEEE, 2021).

Tyrinopoulos, Y. & Antoniou, C. Public transit user satisfaction: variability and policy implications. Transp. Policy 15, 260–272 (2008).

Hollander, J. B. et al. Seeing the city: using eye-tracking technology to explore cognitive responses to the built environment. J. Urban. 12, 156–171 (2019).

Zammarchia, G., Contua, G. & Frigaua, L. Using eye-tracking to evaluate the viewing behavior on tourist landscapes. In ASA 2021 Statistics and Information Systems for Policy Evaluation 127, 141–146 (2023).

Schrammel, J. et al. Attentional behavior of users on the move towards pervasive advertising media. In Pervasive Advertising (eds Müller, J., Alt, F. & Michelis, D.) 287–307 (Springer, 2011).

Piao, G., Zhou, X., Jin, Q. & Nishimura, S. Capturing unselfconscious information seeking behavior by analyzing gaze patterns via eye tracking experiments. In IEEE Conference Anthology, China (IEEE, 2013).