Abstract

Africa is experiencing the impacts of climate change. While global epidemiological studies using traditional analytical methods to study the relations between climate change and health exist, studies using data science to tackle these topics are increasing. The aim of this study was to identify how data science is being used to understand climate change impacts on health in Africa. We carried out a scoping review to synthesize the evidence of data science applied to understand health outcomes associated with climate change in Africa. Among 100 included articles, several temporal and spatial analytical tools and models were applied to determine the relationships between climate change factors and health outcomes for morbidity and mortality. For example, early warning systems for malaria were the most studied adaptation intervention. Africa has a wealth of evidence for addressing the health impacts of climate change to inform solutions for Africa and other countries around the world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change has significantly influenced the landscape of human health risks and outcomes in the 21st century1,2,3. Health threats stemming from the impacts of climate change on the environment include meteorological changes that result in an increased frequency and magnitude of extreme weather events, such as floods, droughts, heatwaves, and wildfires4. These climate changes are associated with changes in the incidence, prevalence, spatial, and temporal distribution of diseases and adverse health outcomes5.

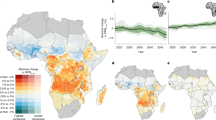

Climate change projections for Africa are considered dire against the backdrop of Africa’s existing challenges, such as poverty, inequality, food insecurity and conflict6, exacerbating Africa’s low adaptive capacity to climate change pressures and shocks7. Ambient temperatures in Africa have been steadily rising by ~0.3°C/decade between 1991 and 2021, and 2021 was among the top five warmest years on record8. Mean ambient temperatures for Africa are projected to be between 4 and 6 °C warmer by 21009, and precipitation is anticipated to change in distribution and intensity across the continent10.

Data science may be helpful for Africa to help coordinate and advance African health data infrastructure and initiatives11. Improvements in data science may advance research on climate change-related health risks, decision-making, and the prioritization of investment in adaptation interventions for the benefit of public health. In addition, there is a need to evaluate the necessity of climate health adaptation to inform the development of prioritization frameworks for decision-makers. Typically, epidemiological studies have been conducted to understand the associations between climate change and associated health outcomes and impacts on health systems to inform prevention activities and solutions aimed at protecting human health and well-being. Data science plays a crucial role in analyzing complex datasets and generating predictive models that can enhance the accuracy of early warning systems11.

Environmental health epidemiology is underpinned by established biostatistical modeling techniques that remain important12. However, as data sets grow in diversity, size and complexity, the need for data science techniques, such as machine learning, advanced statistics, and astute data management has arisen12. Statistical programming, sophisticated computational modeling and machine learning approaches, working with complex, imperfect, real-world structured and unstructured datasets, and rigorously critiquing data science-based research in environmental health are now critical skills needed when conducting environmental health epidemiological studies13.

Recently, data science and computational science have been used in public health sciences14. Data science has helped to resolve some of the methodological challenges in environmental health research, for example, high-dimensional outcomes and exposure, and the creation of prediction models (essential when trying to understand climate change). This scoping review synthesizes the existing evidence on how data science has been used to assess the relationships between climate change and health impacts in Africa to provide evidence to inform design and development of appropriate interventions to prevent adverse climate change-related adverse health impacts in Africa. While previous scoping reviews have considered climate change impacts on mental health15, child health16 and neurological health17, none of these reviews have used data science as an inclusion criterion hence our consideration that this may be the first review of its kind.

Results

Data science approaches applied in climate change and health research in Africa

The full article extractions are provided in the Supplementary material (Table S3). Among the 100 retrieved and included studies, the data science approaches applied included temporal data analysis (n = 28), spatial data analysis (n = 10), modeling of temporal data (n = 88), modeling of spatial data (n = 11) and validation of temporal data (n = 4) as illustrated in Tables 1 and 2.

Studies that used both data science and traditional approaches

Of the 100 studies, only one study compared the validity and integrity of the data science methods employed in the analysis. Sehlabana et al.18 (Table S3) compared classical and Bayesian methods of estimation when modeling malaria incidence in Limpopo province of South Africa18. Classical models used were the Poisson Regression Model, Negative Binomial Model and the Maximum Likelihood Estimation. The Bayesian approach was adopted with the Computation of Negative Binomial Using Bayesian Estimation. Both the Bayesian and the classical frameworks had similar results in terms of a negative relationship between malaria incidence and rainfall. However, the frameworks differed as the Bayesian framework indicates that an increase in Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and day temperature are associated with malaria incidence, whereas the classical framework does not provide evidence of a relationship between these elements. Additionally, the Bayesian framework identified an upward trend in malaria incidence over the study period, while the classical method failed to identify any particular trends.

Climate change and health impacts findings

The greatest number of articles were about malaria followed by all-cause mortality (Fig. 1). Specific findings of associations between climate variables and health outcomes are given in Tables 3–5 and mentioned by communicable and NCDs below. The most commonly used data science methods to study malaria, cholera, diarrhea, and meningitis include generalized additive models (GAM), Poisson and negative binomial regression, generalized linear and mixed models, Bayesian spatial and spatiotemporal models, time series analysis, and spatial analysis tools such as Moran’s I, Maxent, and GIS-based approaches.

Communicable diseases: vector-borne diseases

Malaria emerged as the most frequently studied vector-borne disease, with 38 articles. Most of these studies found that malaria incidence or prevalence increased during warmer and wetter conditions. Other vector-borne diseases, such as Rift Valley fever19, yellow fever20, and dengue fever21 were each the subject of a single article (Table S3)19,20,21.

Communicable diseases: diarrhea and cholera

Diarrhea and cholera were reported by four (Seidu et al., Asare et al., Alemayehu et al., Lee et al.,)22,23,24,25 and six (Mendelsohn et al., Fernández et al., Paz, Jutla et al., Arabi, Charnley)26,27,28,29,30,31 articles respectively. Most cholera studies found that elevated temperatures followed by heavy rain increased the risk of cholera outbreaks (Table S3).

Communicable Diseases: COVID-19

COVID-19 was reported as a health outcome in four articles (Endeshaw et al., Khalis, et al., Phiri et al., Zio et al., (Table S3)32,33,34,35. Some of these studies identified increased wind speed, humidity, rainfall, and concentrations of particulate matter and ozone as risk factors for COVID-19 infection.

Communicable diseases: respiratory diseases (tuberculosis, influenza, pneumonia)

The burden of respiratory diseases such as tuberculosis (TB), influenza, and pneumonia is influenced by climate change. In general, TB incidence increases with rising rainfall and temperature36 while influenza tends to spread with lower temperatures and higher relative humidity37 (Table S3). Pneumonia prevalence appears as a seasonal phenomenon but historical data is inconsistent and recent studies have shown a marked association between increased hospital admissions and lower temperatures and relative humidity (Table S3)38.

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs)

Cardiovascular conditions such as stroke were reported in three studies that found a strong association between these diseases and increased temperatures, as well as heatwaves (Table S3)39,40,41. Additionally, six articles referenced malnutrition, reduced weight and stunting, conditions that have been linked to high temperatures and below average rainfall (Table S3)42,43,44,45,46,47. Additionally, increased temperature and rainfall, particularly during the first and third trimesters of pregnancy, are positively associated with stunting (Table S3)43. One article (Ibekwe et al.) discussed skin diseases, such as atopic dermatitis, which is exacerbated by higher precipitation, humidity, cloud cover, temperature, and ultraviolet (UV) index (Table S3)48.

Climate change and health solutions in data science studies

Of the articles included in the analysis, the majority failed to identify any solutions or interventions. The most common solution (n = 10/100 articles) identified was for the data provided to be used to create or improve early warning systems (Alemayehu et al., Luque Fernández et al., Jutla et al., Attaway et al., Batiano et al., Tompkins et al., Kitawa and Asfaw, Faye et al., Ermert et al.)25,27,29,48,49,50,51,52,53,54. This solution was based on the seasonality of diseases (such as cholera and malaria), and the ability of the articles to model the occurrence of outbreaks. In six articles, (Chapman et al., Jankowska et al., Bunker et al., Diboulo et al., Kulkarni et al., Matthew, 2020)45,55,56,57,58,59 (Table S3), while they did not provide a solution or intervention, the authors indicated that the data and outcomes reported in their studies were able to identify risk areas based on climatic and non-climatic factors; hence, this evidence would be instrumental in creating more effective prevention programmes. Finally, two (Lee et al., Wu et al.)24,60 (Table S3) articles suggested that campaigns centered on raising awareness or educating the public should be used to improve the understanding of the impacts of weather and climate on health.

Regional distribution of research activity

Fig. 2 categorizes the number of articles conducted in each country in the continent, ranging from fewer than two articles to 18 articles. Most climate change-related health articles were from East Africa (28%), particularly in Ethiopia and Kenya, followed by West Africa (28%) and southern Africa (21%).

First authors’ country of institutional affiliation

The first authors’ country of institutional affiliation for each article were included in the extracted findings (see Table S3) and indicated that there were more articles published by authors affiliated with institutions based in the United States of America (USA) (16%) than any other country (Fig. 3). Following this was South Africa and Ethiopia that had 9% and 8% of first author affiliations, respectively. Most notably, almost half of all studies (48%) were conducted by authors whose primary affiliation was outside of Africa, predominantly in Europe or the USA.

Funding supporting data science projects on climate change and health

The majority of the articles presented projects that were funded by donors, organizations and institutions from countries in the northern hemisphere (see the last column of Table S3). Funding originating from the USA and countries from Europe, the European Commission and the UK far exceeded funding originating from African institutions and organizations, e.g., African Academy of Sciences, African Public Health Research Centre and the South African Medical Research Council.

Discussion

Data science has the capacity to identify and characterize solutions and interventions that can more effectively improve environmental and public health outcomes in Africa61. This review explored the data science methods and the health outcomes in response to different climate change exposures. The review is also the first attempt to identify solutions and interventions derived from data science methods by addressing climate change threats to reduce detrimental health outcomes in Africa.

Here, the review of 100 studies applying data science methods to climate change and health research in Africa revealed a strong concentration on communicable diseases, particularly malaria, which was the most frequently studied vector-borne disease. Warmer and wetter conditions were consistently linked to increased malaria incidence, while diarrheal diseases, cholera, and respiratory illnesses such as tuberculosis, influenza, and pneumonia also demonstrated sensitivity to climatic variability. Non-communicable diseases, including cardiovascular conditions, malnutrition, and dermatological disorders, were likewise associated with elevated temperatures, rainfall extremes, and heatwaves. The majority of studies employed advanced modeling techniques—such as Bayesian spatiotemporal approaches, generalized additive models, and GIS-based spatial analyses—underscoring the utility of data science in identifying and quantifying health risks linked to climate variability.

Despite the methodological advances, relatively few studies translated findings into actionable solutions. Among those that did, the most common proposals included strengthening or developing early warning systems for climate-sensitive diseases and leveraging data outputs to identify geographic and population-level hotspots for targeted prevention. However, only a minority of articles addressed public health interventions directly, with some calling for improved awareness campaigns. The analysis highlighted an imbalance in research production: while East and West Africa hosted the largest share of studies, nearly half of the first authors were based outside Africa, primarily in the USA and Europe. This trend was mirrored in funding patterns, where support was predominantly sourced from Northern Hemisphere donors and institutions, reflecting both the global significance of the issue and persistent gaps in African-led capacity and ownership of climate–health research.

Climate change and environmental factors are complex and interactive. The climatic variables and their interactions with health outcomes and disease agents discussed in many of the articles in this study highlighted the complexity of datasets that can be managed by data science methods. Climate change frequently causes simultaneous exposure to several environmental risks, both directly and indirectly, and include variables such as severe temperatures, air pollution, and water scarcity62. Data science provides the tools needed to study interactions between complex datasets and understand how they affect health outcomes63. Researchers can obtain insights into how multiple environmental factors influence illness risk by constructing models that account for these complex relationships, resulting in evidence to inform more comprehensive and effective health interventions13. The scalability of computational data is critical for managing the massive amounts of data required for thorough climate and health assessments64. As the volume and complexity of data increase, it is critical to provide scalable computational frameworks capable of handling massive datasets and sophisticated models. Furthermore, resolving dimensionality difficulties, such as choosing essential variables for specific models, is critical for improving the accuracy and usefulness of data science research studies64.

Given that climate change is affecting the patterns of communicable diseases and NCDs65,66, spatio-temporal analyses of the associations between climate variables and health outcomes is crucial, as it allows us to observe changes in geographical and temporal distribution patterns. This evidence is likely to support climate actions that address the prevalence and geographical extent of diseases and their climatic drivers. Spatio-temporal analysis presents a valuable opportunity to enhance our understanding of how climate change affects disease patterns. By examining the geographical and temporal distribution of climate variables and health outcomes, data scientists can identify trends and correlations that inform targeted climate actions.

Robust data collection and management systems are crucial for applying data science methods to climate change and health. Although there is a growing trend of investment in digital climate health systems, challenges persist in areas such as data quality, completeness, and timeliness67. Despite these challenges, opportunities exist to leverage the advancements in digital transformation, including increased connectivity and mobile phone usage. There is also an opportunity to harness data science methods to create and understand new forms of datasets, such as machine learning of seasonal topographical data68. The emergence of generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) (large language models) can facilitate interactive collection of a variety of datasets and dissemination of data science solutions to the population in novel ways that are impossible with the current approaches67,69.

One of the barriers to effective data science in Africa is the lack of capacity for adequate data infrastructure70. Thus, many countries in Africa rely on traditional statistical methods that are less data-intensive, which often results in gaps in the analyzed health data. For instance, access to quality data from hospital records and civil registries is limited, affecting the ability to make evidence-based policy decisions71. The reliance on less sophisticated data collection methods exacerbates these issues, making it challenging to develop robust data repositories and predictive models.

The reliance on traditional statistical methods, which are less data-intensive, highlights the lack of access to comprehensive health data (e.g., hospital records, civil registries). Data science techniques require large-scale data. Therefore, investment to support infrastructure and skilled staffing are key elements of developing and maintaining quality data repositories, such as electronic hospital records61. Open data initiatives, cross-border and community-driven data collection modalities should also be considered in this endeavor72.

Vector-borne diseases are more widely studied in connection with climate change, as temperature, rainfall patterns and humidity can directly influence the habitats and behaviors of vectors leading to shifts in disease transmission seasons72,73,74. Some diseases have seasonal cycles that respond to climatic factors and are well-documented in Africa75. However, several non-climatic factors influence transmission as well. Tuberculosis has been recognized as a bacterial disease that is climate sensitive but complicated by several other factors associated with socioeconomic conditions, such as crowded housing and malnutrition, HIV coinfection, diabetes, smoking, alcohol use, and sensitivity of children and the elderly76. Thus, the relationship between climate change and diseases that are not transmitted by vectors can be more complex and indirect. Data science is able to use a variety of variables and complex datasets to find links between climatic variables and the spread of diseases by (1) identifying patterns of diseases occurrence in relation to climate, (2) the development of predictive models to forecast future climate conditions and associated disease risk and (3) establishing associations between pathways/mechanisms of disease and climate variables77.

While there is a well-established focus on febrile and vector-borne diseases in Africa, particularly in malaria-endemic regions, NCDs have not received the same level of research attention78. This imbalance persists even though NCDs are contributing to the disease burden on the continent. The potential of data science to illuminate the impacts of climate change on NCDs, and to identify novel approaches for prevention and management, remains untapped. The viability of data science in identifying the potential impact of climate change on NCDs cannot be underestimated, considering the significance of this phenomenon in exploring unique approaches for addressing the increasing burden of NCDs in Africa79. Promoting specialized multidisciplinary research pivots targeted at applying environmental and climate data to harness the gains of data science to address the burden of NCDs in Africa would be promising in addressing this gap. This approach would extend the frontiers of understanding the impact of climate change on NCDs, thereby offering new prevention and treatment opportunities for NCDs management in Africa.

There were some study limitations. The terminology related to climate change and human health, as well as key concepts in this review, is evolving, and new terms may not have been encompassed in our search strategy, which may have resulted in some literature being missing. Within the context of data science, a new and evolving field, there are bound to be new terms associated with these broader topics. While we searched five databases, we may have missed some peer-reviewed literature. In anticipation of this challenge, we searched the reference lists of all included articles to identify any additional literature that may be relevant to the review. Also, we only included English articles and articles written in other languages were not included. Another limitation was that we did not specifically include tropical neglected diseases in our search terms. As this was a scoping review with a very broad topic, we did not conduct a quality assessment of the included articles and this is noted as a limitation. The diversity of data science methods and health outcomes assessed precludes a formal quality assessment or the application of risk of bias tools in this review. We also did not investigate missingness in the data that were presented in the articles included in the review.

The primary focus of this scoping review was on synthesizing existing literature to explore how data science is being applied in public health research, rather than presenting new analytical work by the extensive list of authors. Our contribution lies in the analysis and interpretation of trends across studies, rather than the application of data science techniques ourselves, however, this may be a path for future research.

This scoping review highlights the need for investment into training and retaining data scientists on the African continent to advance a region-specific climate and health agenda. The lack of solutions identified further amplifies the need for more specialized data scientists who will be able to bridge the divide between scientific evidence and action. We also identified the underutilization of data science for automated data analysis which would be a valuable contribution to resource constrained countries.

Finally, this study makes a significant contribution to global public health by synthesizing evidence on how data science methods can illuminate the links between climate variability and health outcomes in Africa, a region disproportionately vulnerable to climate change. By highlighting both communicable and non-communicable disease risks, as well as identifying gaps in intervention design and African-led research, the review provides a foundation for strengthening climate–health surveillance, early warning systems, and adaptation planning. Importantly, the findings underscore the urgency of expanding locally driven, well-funded research and policy responses, ensuring that African institutions are central to generating and applying evidence to protect the health of their populations in the face of accelerating climate risks.

Methods

Our search was informed by the conceptual framework adapted from Helldén et al.16 in Fig. 4. Due to the complex nature of the topic and the possible wide range of studies addressing it, a scoping review method was selected using the Joanna Briggs Institute framework80 adapted from Arksey and O’Malley81 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR)82, We applied the following steps: (i) developing the objectives and questions; (ii) developing the search strategy; (iii) identifying the inclusion and exclusion criteria; (iv) conducting extraction and charting of results; (v) undertaking expert consultation; (vi) presenting the results; and (vii) developing the discussion, conclusion and implications for research and practice. The protocol was not registered prior to execution of the study.

Defining data science

We applied the National Institute of Health Strategic Plan for Data Science definition of data science as “the interdisciplinary field of inquiry in which quantitative and analytical approaches, processes, and systems are developed and used to extract knowledge and insights from increasingly large and/or complex sets of data.”83 Data science encompasses a wide range of topics, including data, big data, blockchain analytics, digital technology, mobile technology and informatics63. It also covers methods useful for spatial data analysis, such as geospatial analysis, image processing and remote sensing84,85. Data analytics, artificial intelligence algorithms, complex systems approaches and complex networks algorithms uncover patterns and solve complex problems86. Additionally, data science methodologies include time series analysis, computational analysis and modeling and regression analysis and modeling, which include multi-level modeling and time-to-event analysis (please see the glossary in the Supplementary material A file for a definition of each of these terms)87.

Defining climate change

Long-term significant changes in temperature and weather patterns are referred to as climate change88. Natural processes, such as fluctuations in the solar cycle, sea spray and volcanic eruptions occur. However, since the 1800s, human activities, primarily the combustion of fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas, have been the primary cause of climate change89.

Defining human health

The World Health Organization defines human health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”.90 Regarding health outcomes, we used the definition of general morbidity to denote a morbidity outcome as “a value describing the presence of disease in the population, or the degree of risk of an event”.91 We used the mortality rate definition of “a measure of the frequency of deaths in a defined population over a certain period of time”.76 The health outcomes included in this review include non-communicable (NCDs), communicable diseases and all-cause mortality. Non-communicable diseases are commonly referred to as chronic diseases and are non-transmissible diseases of often long duration, including mental health conditions, stroke, heart disease, cancer, diabetes and chronic lung disease92. Communicable diseases encompass contagious diseases caused by transmission of an infective agent and include vector-borne diseases such as malaria or Rift Valley fever93.

Eligibility criteria

We followed the PECOS (Population, Exposure, Concept/Context, Outcome and Study design)94 framework in identifying our eligibility criteria. The framework guidance was discussed with an information specialist. Studies eligible for inclusion had to meet the following criteria:

-

Population: Studies conducted in Africa with an emphasis placed on groups who are vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, e.g., infants and children (infants and children are different, primarily in their age and developmental stage; infants are typically defined as babies from birth up to 1 year old, while children encompasses a broader age range, generally from infancy through puberty), older persons, people with pre-existing/chronic diseases, and outdoor workers.

-

Exposure: Studies that assessed environmental factors, agents or exposures related to climate change, such as heat, heatwaves, temperature, floods, and droughts.

-

Concept/Context: Literature focused on climate change in an African setting.

-

Outcome: Outcomes related to climate change, including climate change-related morbidities or mortalities.

-

Study designs: Primary studies/original research (qualitative and quantitative) that used or investigated the use of data science to address health outcomes caused by climate change.

Exclusion criteria

Articles were excluded for the following reasons:

-

Population: Studies conducted in populations outside the African continent.

-

Exposure: Studies that failed to assess environmental factors related to climate change, such as pesticides and heavy metals.

-

Concept/Context: Studies that excluded countries in Africa or the African continent.

-

Outcomes: Studies that did not report human health impacts.

-

Study designs/type of article: Studies that did not apply data science. Conference abstracts, books, book chapters, book reviews, protocols, animal studies, and studies without full text.

Search strategy

We first conducted a pilot search strategy with an information specialist to enhance our search precision. A comprehensive literature search was then conducted after the pilot search in five relevant electronic databases selected to cover both health and climate topics: Web of Science Core Collection (accessed via Web of Science); Scopus (accessed via Elsevier); CAB Abstracts (accessed via Web of Science/OVID); MEDLINE; and EMBASE. The search period was from the inception of the database (no limitations) to 18 October 2023 for articles written in English. In addition, reference lists of eligible peer-reviewed articles were manually searched for additional articles relevant to the scoping review. The databases were searched for relevant articles using text words and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms as part of the search strategy for data science, climate change, and solutions to prevent adverse associated human health outcomes, as defined above, including all literature added to the database until the date of the search (i.e., 31 July 2023). The text words and MeSH terms included those identified below while the full set of search terms is included in the Supplementary material (Table S1):

-

Methods: Methods like data science, crowdsourcing, artificial neural networks, database systems, classification techniques, machine learning and more.

-

Exposures: Climate change, extreme weather events, natural disasters (i.e., drought, floods, landslides, fires, dust storms or windblown dust, heatwaves, hurricanes, tropical cyclones, storm surges and more).

-

Outcomes: Health impacts, such as mortality, morbidity, diet, nutrition, mobility, injury, and mental health.

-

Solutions: Interventions, implementation, climate adaptation, adaptive capacity, and resilience.

Study selection

The search results were consolidated, checked and managed in EndNoteTM version 2095 and Rayyan (https://www.rayyan.ai/)96. Rayyan was used for semi-automation of the initial screening of titles and abstracts. Four reviewers (C.W., A.J., S.M., and T.K.) independently screened the titles and abstracts for relevance against the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed above. Subsequently, the authors independently screened the full texts of potentially eligible articles for inclusion and exclusion. During the article selection phase, disagreements between two authors were resolved through discussion with another author (C.Y.W.) to reach a consensus. We initially retrieved 15,711 records. Following deduplication, the remaining 15,249 records were then imported to an online reviewing platform called Rayyan, where a second round of deduplication removed 415 duplicates. The remaining 14,834 records were screened by four reviewers (C.W., T.K., A.J., S.M., C.Y.W.) who independently assessed the title and abstract of each record for inclusion. Full texts were sourced for 140 records that met the inclusion criteria. The full texts were assessed for eligibility and if they failed to meet the eligibility criteria, the reason for exclusion was as detailed in the PRISMA diagram (Fig. 5). This resulted in 100 articles being included in the final review. Since this was a scoping review, articles were not assessed for methodological quality or risk of bias as is done for systematic reviews. This is aligned with our aim to identify and map existing literature on the use of data science to address climate change-related health problems in Africa.

Data charting and synthesis

All authors assisted to independently extract the article data using a piloted data extraction form in Microsoft Word TM. Data extracted from eligible studies included the surname and initial of the first author, year of publication, the first author’s country of affiliation, the country where the study was conducted, study design, study period, climate change variables used, health outcomes, data science technique (method), suggested intervention or solutions (if any) and key findings (i.e., associations between climate change and human health).

Analysis

The charted data were checked and categorized by three authors (C.W., S.B., and C.Y.W.) to ensure uniformity in the reporting of outcomes for effective tabulation. Data synthesis involved analyzing findings from the identified articles using thematic analysis approaches. Since the scope of data science is vast, the included studies were broadly categorized. We categorized articles by data science method and then we applied three high-level categories for reporting health outcomes: all-causes, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and communicable diseases. Where possible, we considered sex-based differences and other socio-demographic characteristics (i.e., socio-economic status, age) mentioned in the studies.

Data availability

All the data reported in this review article are included in the body of the manuscript and in the supplementary tables.

References

Romanello, M. et al. The 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels. Lancet 400, 1619–1654 (2022).

Rocha, J., Oliveira, S., Viana, C. M. & Ribeiro, A. I. Climate change and its impacts on health, environment and economy. in One Health 253–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-822794-7.00009-5 (Elsevier, 2022).

Zhao, Q. et al. Global climate change and human health: pathways and possible solutions. Eco Environ. Health 1, 53–62 (2022).

Ebi, K. L. et al. Extreme weather and climate change: population health and health system implications. Annu. Rev. Public Health 42, 293–315 (2021).

Bianco, G. et al. Projected impact of climate change on human health in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ Glob. Health 8, e015550 (2024).

Muyambo, F., Belle, J., Nyam, Y. S. & Orimoloye, I. R. Climate-change-induced weather events and implications for urban water resource management in the Free State Province of South Africa. Environ. Manag. 71, 40–54 (2023).

Adjei, V. & Amaning, E. F. Low adaptive capacity in Africa and climate change crises. J. Atmos. Sci. Res. 4, https://doi.org/10.30564/jasr.v4i4.3723 (2021).

Wright, C. Y. et al. Climate change and human health in Africa in relation to opportunities to strengthen mitigating potential and adaptive capacity: strategies to inform an African “Brains Trust”. Ann Glob Health 90, 7 (2024).

Engelbrecht, F. et al. Projections of rapidly rising surface temperatures over Africa under low mitigation. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 085004 (2015).

Bobde, V., Akinsanola, A. A., Folorunsho, A. H., Adebiyi, A. A. & Adeyeri, O. E. Projected regional changes in mean and extreme precipitation over Africa in CMIP6 models. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 074009 (2024).

Adebamowo, C. A. et al. The promise of data science for health research in Africa. Nat. Commun. 14, 6084 (2023).

Comess, S. et al. Bringing big data to bear in environmental public health: challenges and recommendations. Front. Artif. Intell. 3, 31 (2020).

Choirat, C., Braun, D. & Kioumourtzoglou, M.-A. Data science in environmental health research. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 6, 291–299 (2019).

Goldsmith, J. et al. The emergence and future of public health data science. Public Health Rev. 42, 1604023 (2021).

Charlson, F. et al. Climate change and mental health: a scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 4486 (2021).

Helldén, D. et al. Climate change and child health: a scoping review and an expanded conceptual framework. Lancet Planet Health 5, e164–e175 (2021).

Louis, S. et al. Impacts of climate change and air pollution on neurologic health, disease, and practice. Neurology 100, 474–483 (2023).

Sehlabana, M. A., Maposa, D. & Boateng, A. Modelling malaria incidence in the Limpopo Province, South Africa: comparison of classical and Bayesian methods of estimation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 5016 (2020).

Gikungu, D. et al. Dynamic risk model for Rift Valley fever outbreaks in Kenya based on climate and disease outbreak data. Geospat. Health 11, 377 (2016).

Hamlet, A. et al. The seasonal influence of climate and environment on yellow fever transmission across Africa. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 12, e0006284 (2018).

Ouattara, C. A. et al. Climate factors and dengue fever in Burkina Faso from 2017 to 2019. J. Public Health Afr. 13, 2145 (2022).

Seidu, R., Stenström, T. A. & Löfman, O. A comparative cohort study of the effect of rainfall and temperature on diarrhoeal disease in faecal sludge and non-faecal sludge applying communities, Northern Ghana. J. Water Clim. Chang. 4, 90–102 (2013).

Asare, E. O., Warren, J. L. & Pitzer, V. E. Spatiotemporal patterns of diarrhea incidence in Ghana and the impact of meteorological and socio-demographic factors. Front. Epidemiol. 2, https://doi.org/10.3389/fepid.2022.871232 (2022).

Lee, T. T. et al. Understanding diarrhoeal diseases in response to climate variability and drought in Cape Town, South Africa: a mixed methods approach. Infect. Dis. Poverty 12, 76 (2023).

Alemayehu, B., Ayele, B. T., Melak, F. & Ambelu, A. Exploring the association between childhood diarrhea and meteorological factors in Southwestern Ethiopia. Sci. Total Environ. 741, 140189 (2020).

ARABI, M. & NGWA, M. C. Modeling the relationship between weather parameters and cholera in the City of Maroua, Far North Region, Cameroon. Geogr. Tech. 14, 1–13 (2019).

Jutla, A. et al. Satellite based assessment of hydroclimatic conditions related to cholera in Zimbabwe. PLoS One 10, e0137828 (2015).

Paz, S. Impact of temperature variability on cholera incidence in Southeastern Africa, 1971–2006. Ecohealth 6, 340–345 (2009).

Luque Fernández, M. Á. et al. Influence of temperature and rainfall on the evolution of cholera epidemics in Lusaka, Zambia, 2003–2006: analysis of a time series. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 103, 137–143 (2009).

Mendelsohn, J. & Dawson, T. Climate and cholera in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: the role of environmental factors and implications for epidemic preparedness. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 211, 156–162 (2008).

Charnley, G. E. C. et al. Exploring relationships between drought and epidemic cholera in Africa using generalised linear models. BMC Infect. Dis. 21, 1177 (2021).

Zio, S. et al. Multi-outputs Gaussian process for predicting Burkina Faso COVID-19 spread using correlations from the weather parameters. Infect. Dis. Model. 7, 448–462 (2022).

Phiri, D. et al. Spread of COVID-19 in Zambia: an assessment of environmental and socioeconomic factors using a classification tree approach. Sci. Afr. 12, e00827 (2021).

Khalis, M. et al. Relationship between meteorological and air quality parameters and COVID-19 in Casablanca region, Morocco. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 4989 (2022).

Endeshaw, F. B. et al. Effects of climatic factors on COVID-19 transmission in Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 12, 19722 (2022).

Kharwadkar, S., Attanayake, V., Duncan, J., Navaratne, N. & Benson, J. The impact of climate change on the risk factors for tuberculosis: a systematic review. Environ Res. 212, 113436 (2022).

Lane, M. A. et al. Climate change and influenza: a scoping review. J. Clim. Chang. Health 5, 100084 (2022).

Pedder, H. et al. Lagged association between climate variables and hospital admissions for pneumonia in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 191 (2021).

Bo, W. et al. A progressive prediction model towards home-based stroke rehabilitation programs. Smart Health 23, 100239 (2022).

Kynast-Wolf, G., Preuß, M., Sié, A., Kouyaté, B. & Becher, H. Seasonal patterns of cardiovascular disease mortality of adults in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Trop. Med. Int. Health. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02586.x (2010).

Makunyane, M. S., Rautenbach, H., Sweijd, N., Botai, J. & Wichmann, J. Health risks of temperature variability on hospital admissions in Cape Town, 2011–2016. Int J. Environ. Res Public Health 20, 1159 (2023).

Thiede, B. C. & Strube, J. Climate variability and child nutrition: findings from sub-Saharan Africa. Glob. Environ. Chang. 65, 102192 (2020).

Randell, H., Gray, C. & Grace, K. Stunted from the start: early life weather conditions and child undernutrition in Ethiopia. Soc. Sci. Med 261, 113234 (2020).

McLaughlin, S. M., Bozzola, M. & Nugent, A. Changing climate, changing food consumption? impact of weather shocks on nutrition in Malawi. J. Dev. Stud. 59, 1827–1848 (2023).

Jankowska, M. M., Lopez-Carr, D., Funk, C., Husak, G. J. & Chafe, Z. A. Climate change and human health: Spatial modeling of water availability, malnutrition, and livelihoods in Mali, Africa. Appl. Geogr. 33, 4–15 (2012).

Grace, K., Davenport, F., Funk, C. & Lerner, A. M. Child malnutrition and climate in Sub-Saharan Africa: an analysis of recent trends in Kenya. Appl. Geogr. 35, 405–413 (2012).

Amondo, E. I., Nshakira-Rukundo, E. & Mirzabaev, A. The effect of extreme weather events on child nutrition and health. Food Secur. 15, 571–596 (2023).

Ibekwe, P. U. & Ukonu, B. A. Impact of weather conditions on atopic dermatitis prevalence in Abuja, Nigeria. J. Natl. Med Assoc. 111, 88–93 (2019).

Attaway, D. F., Jacobsen, K. H., Falconer, A., Manca, G. & Waters, N. M. Risk analysis for dengue suitability in Africa using the ArcGIS predictive analysis tools (PA tools). Acta Trop. 158, 248–257 (2016).

Ermert, V., Fink, A. H. & Paeth, H. The potential effects of climate change on malaria transmission in Africa using bias-corrected regionalised climate projections and a simple malaria seasonality model. Clim. Chang. 120, 741–754 (2013).

Faye, M., Dème, A., Diongue, A. K. & Diouf, I. Impact of different heat wave definitions on daily mortality in Bandafassi, Senegal. PLoS One 16, e0249199 (2021).

Kitawa, Y. S. & Asfaw, Z. G. Space-time modelling of monthly malaria incidence for seasonal associated drivers and early epidemic detection in Southern Ethiopia. Malar. J. 22, 301 (2023).

Tompkins, A. M., Colón-González, F. J., Di Giuseppe, F. & Namanya, D. B. Dynamical malaria forecasts are skillful at regional and local scales in Uganda up to 4 months ahead. Geohealth 3, 58–66 (2019).

Bationo, C. et al. Malaria in Burkina Faso: a comprehensive analysis of spatiotemporal distribution of incidence and environmental drivers, and implications for control strategies. PLoS ONE 18, e0290233 (2023).

Chapman, S. et al. Past and projected climate change impacts on heat-related child mortality in Africa. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 74028 (2022).

Bunker, A., Sewe, M. O., Sié, A., Rocklöv, J. & Sauerborn, R. Excess burden of non-communicable disease years of life lost from heat in rural Burkina Faso: a time series analysis of the years 2000–2010. BMJ Open 7, e018068 (2017).

Diboulo, E. et al. Weather and mortality: a 10 year retrospective analysis of the Nouna Health and Demographic Surveillance System, Burkina Faso. Glob. Health Action 5, 6–13 (2012).

Kulkarni, M. A. et al. 10 years of environmental change on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro and its associated shift in malaria vector distributions. Front. Public Health 4, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00281 (2016).

Matthew, O. J. Investigating climate suitability conditions for malaria transmission and impacts of climate variability on mosquito survival in the humid tropical region: a case study of Obafemi Awolowo University Campus, Ile-Ife, south-western Nigeria. Int. J. Biometeorol. 64, 355–365 (2020).

Wu, Y. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of mortality associated with short-term temperature variability from 2000–19: a three-stage modelling study. Lancet Planet. Health 6, e410–e421 (2022).

Coker, M. O. et al. Data science training needs in sub-Saharan Africa: implications for biomedical research and therapeutics capacity. Open Res. Afr. 6, 21 (2023).

Ofremu, G. O. et al. Exploring the relationship between climate change, air pollutants and human health: impacts, adaptation, and mitigation strategies. Green Energy Resour. 3, 1000074 (2025).

Subrahmanya, S. V. G. et al. The role of data science in healthcare advancements: applications, benefits, and future prospects. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 191, 1473–1483 (2022).

Malhotra, A. Scalability and performance optimization in big data analytics platforms. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 4, 2857–2864 (2023).

Baker, R. E. et al. Infectious disease in an era of global change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 193–205 (2022).

Siiba, A., Kangmennaang, J., Baatiema, L. & Luginaah, I. The relationship between climate change, globalization and non-communicable diseases in Africa: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 19, e0297393 (2024).

World Bank. Digital Transformation Drives Development in Africa. https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2024/01/18/digital-transformation-drives-development-in-afe-afw-africa (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Machine learning methods in weather and climate applications: a survey. Appl. Sci. 13, 12019 (2023).

Yu, P., Xu, H., Hu, X. & Deng, C. Leveraging generative AI and large language models: a comprehensive roadmap for healthcare integration. Healthcare 11, 2776 (2023).

Mwelwa, J., Boulton, G., Wafula, J. M. & Loucoubar, C. Developing open science in Africa: barriers, solutions and opportunities. Data Sci. J. 19, 31 (2020).

Musa, S. M. et al. Paucity of health data in Africa: an obstacle to digital health implementation and evidence-based practice. Public Health Rev. 44, 1605821 (2023).

Jetzek, T., Avital, M. & Bjorn-Andersen, N. Data-driven innovation through open government data. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 9, 15–16 (2014).

Adeola, A. et al. Rainfall trends and malaria occurrences in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245156 (2019).

Adeola, A. M. et al. Predicting malaria cases using remotely sensed environmental variables in Nkomazi, South Africa. Geospat. Health 14, https://doi.org/10.4081/gh.2019.676 (2019).

Fuhrmann, C. The effects of weather and climate on the seasonality of influenza: what we know and what we need to know. Geogr. Compass 4, 718–730 (2010).

Mathema, B. et al. Drivers of tuberculosis transmission. J. Infect. Dis. 216, S644–S653 (2017).

Zhao, A. P. et al. AI for science: Predicting infectious diseases. J. Saf. Sci. Resil. 5, 130–146 (2024).

Luna, F. & Luyckx, V. A. Why have non-communicable diseases been left behind?. Asian Bioeth. Rev. 12, 5–25 (2020).

Gouda, H. N. et al. Burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2017: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Glob. Health 7, e1375–e1387 (2019).

Jordan, Z., Lockwood, C., Munn, Z. & Aromataris, E. The updated Joanna Briggs Institute model of evidence-based healthcare. Int. J. Evid. Based Health. 17, 58–71 (2019).

Arksey, H. & O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 19–32 (2005).

Tricco, A. C. et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169, 467–473 (2018).

National Institutes of Health. NIH Strategic Plan for Data Science 2025–2030. https://datascience.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2025-05/NIH%20Strategic%20Plan%20for%20Data%20Science%202025-2030.pdf (2025).

Maantay, J. A. & McLafferty, S. Geospatial Analysis of Environmental Health (SpringerLink, 2011).

He, Y. & Weng, Q. High Spatial Resolution Remote Sensing: Data, Analysis, and Applications. (CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, 2018).

Joksimovic, S. et al. Opportunities of artificial intelligence for supporting complex problem-solving: findings from a scoping review. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 4, 100138 (2023).

Sarker, I. H. Data science and analytics: an overview from data-driven smart computing, decision-making and applications perspective. SN Comput. Sci. 2, 377 (2021).

United Nations. What is climate change? https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/what-is-climate-change (2023).

IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647 (2023).

World Health Organization. Health and Well-Being. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/major-themes/health-and-well-being (2023).

Choi, J. et al. Health indicators related to disease, death, and reproduction. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 52, 14–20 (2019).

UNICEF. Non-communicable diseases. https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/noncommunicable-diseases/ (2024).

IPCC. Appendix B.: Glossary of terms. in Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels (eds Masson-Delmotte V. et al.) (2018) (in Press).

Higgins, J. P. T. & Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. www.handbook.cochrane.org (2011).

The Endnote Team. EndNote (Version 2025, 64-bit) [Computer software]. Philadelphia, PA. Clarivate. https://endnote.com/ (2013).

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z. & Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 5, 210 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This manuscript is part of a broader writing project on the State of Data Science for Health in Africa (https://bit.ly/StateDataSciAfrica). The project is led by three Scientific Co-Chairs, Catherine Kyobutungi of the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC, Kenya), Emile R. Chimusa of the Northumbria University Newcastle (United Kingdom), and A. Kofi Amegah of the University of Cape Coast (Ghana). The project is coordinated and supported by the Center for Global Health Studies at the Fogarty International Center, U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC), Wellcome through Grant No. 228261/Z/23/Z, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through Grant No. INV-058418, in collaboration with other partner organizations. The authors are grateful to Catherine Kyobutungi, A. Kofi Amegah, and Jantina de Vries (University of Cape Town) for their insightful comments and useful feedback on various drafts of the manuscript. C.Y.W. receives research funding from the South African Medical Research Council and National Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Y.W. conceptualized the study and was responsible for preparing the first draft of the manuscript. C.W., A.J., and T.K. independently screened the titles and abstracts of the initial set of retrieved articles. C.W., T.K., and C.Y.W. conducted the data analysis. C.Y.W., N.N., B.A., E.B., K.B., S.B., A.G.K., R.N., B.N., B.K.N., A.P.O., T.O., R.Q., S.T., I.S.Z., N.B., E.R.C., and C.W. extracted data from articles, provided input and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wright, C.Y., Jaca, A., Kapwata, T. et al. Using data science to identify climate change and health adverse impacts and solutions in Africa: a scoping review. npj Health Syst. 3, 16 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44401-025-00057-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44401-025-00057-w