Abstract

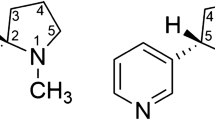

Nicotine presented to the nasal cavity at low concentrations evokes ‘odorous’ sensations, and at higher concentrations ‘burning’ and ‘stinging’ sensations. A study in smokers and nonsmokers provided evidence of a relationship between the experience with the pharmacological action of S-(−)-nicotine and the perceived pleasantness/unpleasantness following nasal stimulation with S-(−)-nicotine. Mecamylamine, a nicotinic acetylcholine-receptor-(nAch-R) antagonist, was able to block painful responses following chemical stimulation of the human tongue and to block responses from the rat's ethmoidal nerve. The aim of our study in humans was to investigate the effects of mecamylamine on the olfactory and the trigeminal chemoreception of nicotine enantiomers. In order to achieve this aim, we determined—before and after mecamylamine—(1) detection thresholds, trigeminal thresholds, and intensity estimates (stimulus intensity) and (2) recorded the negative mucosal potential (NMP) following nasal stimulation with nicotine in a placebo-controlled double blind study (n=15). CO2 was used as a trigeminal and H2S as an olfactory control stimulus. Mecamylamine significantly increased trigeminal thresholds of S-(−)-nicotine and reduced intensity estimates and NMPs following stimulation with nicotine enantiomers, whereas mecamylamine did not influence NMPs and trigeminal intensity estimates following stimulation with CO2. In contrast, mecamylamine did neither influence detection thresholds nor olfactory intensity estimates following stimulation with olfactory nicotine concentrations. These results demonstrate that the trigeminal nasal chemoreception of nicotine enantiomers, in contrast to CO2, is mediated by nAch-Receptors and give evidence that the olfactory chemoreception of nicotine is independent from peripheral nAch-Receptors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

Alimohammadi H, Silver WL (2000). Evidence for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on nasal trigeminal nerve endings of the rat. Chem Senses 25: 61–66.

American Psychiatric Association (1996). Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with nicotine dependence. Am J Psychiatry 153: 1–31.

Cepeda Benito A (1993). Meta-analytical review of the efficacy of nicotine chewing gum in smoking treatment programs. J Consult Clin Psychol 61: 822–830.

Davies HM, Vaught A (1990). Research Cigarettes. University of Kentucky Printing Services: Kentucky.

Dessirier JM, O’Mahony M, Sieffermann JM, Carstens E (1998). Mecamylamine inhibits nicotine but not capsaicin irritation on the tongue: psychophysical evidence that nicotine and capsaicin activate separate molecular receptors. Neurosci Lett 240: 65–68.

Dravnieks A, Masurat T, Lamm RA (1984). Hedonics of odors and odor descriptors. J Air Pollution Control Assoc 34: 752–755.

Eccles R, Jawad MS, Morris S (1989). Olfactory and trigeminal thresholds and nasal resistance to airflow. Acta Otolaryngol Stockh 108: 268–273.

Finger TE, Bottger B, Hansen A, Anderson KT, Alimohammadi H, Silver WL (2003). Solitary chemoreceptor cells in the nasal cavity serve as sentinels of respiration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 8981–8986.

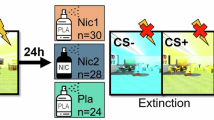

Grusser SM, Heinz A, Flor H (2000). Standardized stimuli to assess drug craving and drug memory in addicts. J Neural Transm 107: 715–720.

Handwerker HO, Kobal G (1993). Psychophysiology of experimentally induced pain. Physiol Rev 73: 639–671.

Hilberg O, Jackson AC, Swift DL, Pedersen OF (1989). Acoustic rhinometry: evaluation of nasal cavity geometry by acoustic reflection. J Appl Physiol 66: 295–303.

Hummel T, Hummel C, Pauli E, Kobal G (1992a). Olfactory discrimination of nicotine-enantiomers by smokers and non-smokers. Chem Senses 17: 13–21.

Hummel T, Livermore A, Hummel C, Kobal G (1992b). Chemosensory event-related potentials in man: relation to olfactory and painful sensations elicited by nicotine. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 84: 192–195.

Hummel T, Schiessl C, Wendler J, Kobal G (1996). Peripheral electrophysiological responses decrease in response to repetitive painful stimulation of the human nasal mucosa. Neurosci Lett 212: 37–40.

Hummel T, Sekinger B, Wolf SR, Pauli E, Kobal G (1997). Sniffin’ sticks’: olfactory performance assessed by the combined testing of odor identification, odor discrimination and olfactory threshold. Chem Senses 22: 39–52.

Kobal G (1985). Pain-related electrical potentials of the human nasal mucosa elicited by chemical stimulation. Pain 22: 151–163.

Kornitzer M, Boutsen M, Dramaix M, Thijs J, Gustavsson G (1995). Combined use of nicotine patch and gum in smoking cessation: a placebo-controlled clinical trial. Prev Med 24: 41–47.

Laviolette SR, van der Kooy D (2004). The neurobiology of nicotine addiction: bridging the gap from molecules to behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci 5: 55–65.

Menini A, Picco C, Firestein S (1995). Quantal-like current fluctuations induced by odorants in olfactory receptor cells (see comments). Nature 373: 435–437.

Papke RL, Sanberg PR, Shytle RD (2001). Analysis of mecamylamine stereoisomers on human nicotinic receptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 297: 646–656.

Renner B, Meindorfner F, Kaegler M, Thuerauf N, Barocka A, Kobal G (1998). Discrimination of R- and S-nicotine by the trigeminal nerve. Chem Senses 29: 602.

Silagy C, Mant D, Fowler G, Lodge M (1994). Meta-analysis on efficacy of nicotine replacement therapies in smoking cessation. Lancet 343: 139–142.

Stein C, Mendl G (1988). The German counterpart to McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain 32: 251–255.

Sutherland G, Stapleton JA, Russell MA, Jarvis MJ, Hajek P, Belcher M et al (1992). Randomised controlled trial of nasal nicotine spray in smoking cessation. Lancet 340: 324–329.

Thuerauf N, Friedel I, Hummel C, Kobal G (1991). The mucosal potential elicited by noxious chemical stimuli with CO2 in rats: is it a peripheral nociceptive event? Neurosci Lett 128: 297–300.

Thuerauf N, Günther M, Pauli E, Kobal G (2002). Sensitivity of the negative mucosal potential to the trigeminal target stimulus CO2 . Brain Res 942: 79–86.

Thuerauf N, Hummel T, Kettenmann B, Kobal G (1993). Nociceptive and reflexive responses recorded from the human nasal mucosa. Brain Res 629: 293–299.

Thuerauf N, Kaegler M, Dietz R, Barocka A, Kobal G (1999). Dose-dependent stereoselective activation of the trigeminal sensory system by nicotine in man. Psychopharmacology 142: 236–243.

Thuerauf N, Kaegler M, Renner B, Barocka A, Kobal G (2000). Specific sensory detection, discrimination, and Hedonic estimation of nicotine enantiomers in smokers and nonsmokers: are there limitations in replacing the sensory components in nicotine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 20: 472–478.

Thuerauf N, Renner B, Kobal G (1995). Responses recorded from the frog olfactory epithelium after stimulation with R(+)- and S(−)-nicotine. Chem Senses 20: 337–344.

Tonnesen P, Norregaard J, Mikkelsen K, Jorgensen S, Nilsson F (1993). A double-blind trial of a nicotine inhaler for smoking cessation. JAMA 269: 1268–1271.

Walker JC, Kendal-Reed M, Keiger CJ, Bencherif M, Silver WL (1996). Olfactory and trigeminal responses to nicotine. Drug Dev Res 38: 160–168.

Westman EC, Behm FM, Rose JE (1995). Airway sensory replacement combined with nicotine replacement for smoking cessation: a randomized, placebo controlled trial using a citric acid inhaler. Chest 107: 1358–1364.

Westman EC, Behm FM, Rose JE (1996). Dissociating the nicotine and airway sensory effects of smoking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 53: 309–315.

Woodruff-Pak DS (2003). Mecamylamine reversal by nicotine and by a partial alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist (GTS-21) in rabbits tested with delay eyeblink classical conditioning. Behav Brain Res 143: 159–167.

Wysocki CJ, Beauchamp GK (1984). Ability to smell androstenone is genetically determined. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81: 4899–4902.

Zattore RJ, Jones-Gotman M (1990). Right-nostril advantage for discrimination of odors. Percept Psychophys 47: 526–531.

Acknowledgements

The research described in this article was supported by Philip Morris USA Inc. (Philip Morris External Research Program/Fellowship). We thank Susanne Schroeder-Thuerauf (Department of Languages for Special Purposes, University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany) and Bruce Bryant (Monell Chemical Senses Center, Philadelphia, PA USA) for helpful suggestions during the preparation of the manuscript and Elfriede Hoh (Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Erlangen-Nürnberg) for assistance during the experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thuerauf, N., Markovic, K., Braun, G. et al. The Influence of Mecamylamine on Trigeminal and Olfactory Chemoreception of Nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacol 31, 450–461 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300842

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1300842

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Does Menopausal Status Affect Dry Eye Disease Treatment Outcomes with OC-01 (Varenicline Solution) Nasal Spray? A Post Hoc Analysis of ONSET-1 and ONSET-2 Clinical Trials

Ophthalmology and Therapy (2023)

-

Nasal Chemesthesis: Similarities Between Humans and Rats Observed in In Vivo Experiments

Chemosensory Perception (2015)

-

Environmental and non-infectious factors in the aetiology of pharyngitis (sore throat)

Inflammation Research (2012)

-

Gustatory, Trigeminal, and Olfactory Aspects of Nicotine Intake in Three Mouse Strains

Behavior Genetics (2012)

-

Olfactory and trigeminal interaction of menthol and nicotine in humans

Experimental Brain Research (2012)