Abstract

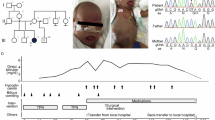

Beckwith–Wiedemann Syndrome (BWS) results from mutations or epigenetic events involving imprinted genes at 11p15.5. Most BWS cases are sporadic and uniparental disomy (UPD) or putative imprinting errors predominate in this group. Sporadic cases with putative imprinting defects may be subdivided into (a) those with loss of imprinting (LOI) of IGF2 and H19 hypermethylation and silencing due to a defect in a distal 11p15.5 imprinting control element (IC1) and (b) those with loss of methylation at KvDMR1, LOI of KCNQ1OT1 (LIT1) and variable LOI of IGF2 in whom there is a defect at a more proximal imprinting control element (IC2). We investigated genotype/epigenotype–phenotype correlations in 200 cases with a confirmed molecular genetic diagnosis of BWS (16 with CDKN1C mutations, 116 with imprinting centre 2 defects, 14 with imprinting centre 1 defects and 54 with UPD). Hemihypertrophy was strongly associated with UPD (P<0.0001) and exomphalos was associated with an IC2 defect or CDKN1C mutation but not UPD or IC1 defect (P<0.0001). When comparing birth weight centile, IC1 defect cases were significantly heavier than the patients with CDKN1C mutations or IC2 defect (P=0.018). The risk of neoplasia was significantly higher in UPD and IC1 defect cases than in IC2 defect and CDKN1C mutation cases. Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed a risk of neoplasia for all patients of 9% at age 5 years, but 24% in the UPD subgroup. The risk of Wilms’ tumour in the IC2 defect subgroup appears to be minimal and intensive screening for Wilms’ tumour appears not to be indicated. In UPD patients, UPD extending to WT1 was associated with renal neoplasia (P=0.054). These findings demonstrate that BWS represents a spectrum of disorders. Identification of the molecular subtype allows more accurate prognostic predictions and enhances the management and surveillance of BWS children such that screening for Wilms’ tumour and hepatoblastoma can be focused on those at highest risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

Elliott M, Maher ER : Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. J Med Genet 1994; 31: 560–564.

Martinez RMY : Clinical features in the Wiedemann–Beckwith syndrome. Clin Genet 1996; 50: 272–274.

Maher ER, Reik W : Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome: imprinting in clusters revisited. J Clin Invest 2000; 105: 247–252.

Turleau C, Degrouchy J, Chavincolin F, Martelli H, Voyer M, Charlas R : Trisomy 11p15 and Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome – a report of 2 cases. Hum Genet 1984; 67: 219–221.

Brown KW, Gardner A, Williams JC, Mott MG, McDermott A, Maitland NJ : Paternal origin of 11p15 duplications in the Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome – a new case and a review of the literature. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1992; 58: 66–70.

Nystrom A, Cheetham JE, Engstrom W, Schofield PN : Molecular analysis of patients with Wiedemann–Beckwith syndrome 2 paternally derived disomies of chromosome-11. Eur J Pediatr 1992; 151: 511–514.

Slavotinek A, Gaunt L, Donnai D : Paternally inherited duplications of 11p15.5 and Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. J Med Genet 1997; 34: 819–826.

Norman A, Read A, Clayton-Smith J, Andrews T, Donnai D : Recurrent Wiedemann–Beckwith syndrome with inversion of chromosome (11)(p11.2p15.5). Am J Med Genet 1992; 42: 638–641.

Tommerup N, Brandt C, Pedersen S, Bolund L, Kamper J : Sex-dependent transmission of Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome – associated with a reciprocal translocation t(9,11)(p11.2,p15.5). J Med Genet 1993; 30: 958–961.

Fisher AM, Thomas NS, Cockwell A et al: Duplication of chromosome 11p15 of maternal origin result in a phenotype that includes growth retardation. Hum Genet 2002; 111: 290–296.

Slatter RE, Elliott M, Welham K et al: Mosaic uniparental disomy in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. J Med Genet 1994; 31: 749–753.

Henry I, Bonaitipellie C, Chehensse V et al: Uniparental paternal disomy in a genetic cancer-predisposing syndrome. Nature 1991; 351: 665–667.

Dutley F, Baumer A, Kayserili H et al: Seven cases of Wiedemann–Beckwith syndrome including the first reported case of mosaic paternal isodisomy along the whole of chromosome 11. Am J Med Genet 1998; 79: 347–353.

Catchpoole D, Lam WWK, Valler D et al: Epigenetic modification and uniparental inheritance of H19 in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. J Med Genet 1997; 34: 353–359.

Hatada I, Ohashi H, Fukushima Y et al: An imprinted gene p57KIP2 is mutated in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Nat Genet 1996; 14: 171–173.

Lam WWK, Hatada I, Ohishi S et al: Analysis of germline CDKN1C (p57KIP2) mutations in familial and sporadic Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome (BWS) provides a novel genotype–phenotype correlation. J Med Genet 1999; 36: 518–523.

Lee M, Debaun M, Randhawa G, Reichard B, Elledge S, Feinberg A : Low frequency of p57KIP2 mutation in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 1997; 61: 304–309.

Hark A, Schoenherr C, Katz D, Ingram R, Levorse J, Tilghman S : CTCF mediates methylation-sensitive enhancer-blocking activity at the H19/Igf2 locus. Nature 2000; 405: 486–489.

Bell A, Felsenfeld G : Methylation of a CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression of the Igf2 gene. Nature 2000; 405: 482–485.

Nakagawa H, Chadwick RB, Peltomaki P, Plass C, Nakamura Y, de la Chapelle A : Loss of imprinting of the insulin-like growth factor II gene occurs by biallelic methylation in a core region of H19-associated CTCF-binding sites in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98: 591–596.

Sparago A, Cerrato F, Vernucci M, Ferrero GB, Silengo MC, Riccio A : Microdeletions in the human H19 DMR result in loss of IGF2 imprinting and Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Nat Genet 2004; 36: 958–960.

Smilinich NJ, Day CD, Fitzpatrick GV et al: A maternally methylated CpG island in KCNQ1 is associated with an antisense paternal transcript and loss of imprinting in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999; 96: 8064–8069.

Lee M, DeBaun M, Mitsuya K et al: Loss of imprinting of a paternally expressed transcript, with antisense orientation to K(V)LQT1, occurs frequently in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome and is independent of insulin-like growth factor II imprinting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999; 96: 5203–5208.

Engel JR, Smallwood A, Harper A et al: Epigenotype–phenotype correlations in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. J Med Genet 2000; 37: 921–926.

Diaz-Meyer N, Day C, Khatod K et al: Silencing of CDKN1C (p57(KIP2)) is associated with hypomethylation at KvDMR1 in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. J Med Genet 2003; 40: 797–801.

Niemitz EL, DeBaun MR, Fallon J et al: Microdeletion of LIT1 in familial Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2004; 75: 844–849.

DeBaun MR, Niemitz EL, McNeil DE, Brandenberg SA, Lee MP, Feinberg AP : Epigenetic alterations of H19 and LIT1 distinguish patients with Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome with cancer and birth defects. Am J Hum Genet 2002; 70: 604–611.

Weksberg R, Nishikawa J, Caluseriu O et al: Tumor development in the Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome is associated with a variety of constitutional molecular 11p15 alterations including imprinting defects at KCNQ1OT1. Hum Mol Genet 2001; 10: 2989–3000.

Bliek J, Maas SM, Ruijter JM et al: Increased tumour risk for BWS patients correlates with aberrant H19 and not KCNQ1OT1 methylation: occurrence of KCNQ1OT1 hypomethylation in familial cases of BWS. Hum Mol Genet 2001; 10: 467–476.

Reik W, Brown KW, Slatter RE, Sartori P, Elliott M, Maher ER : Allelic methylation of H19 and IGF2 in the Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 1994; 3: 1297–1301.

Agathanggelou A, Honorio S, Macartney D et al: Methylation associated inactivation of RASSF1A from region 3p21.3 in lung, breast and ovarian tumours. Oncogene 2001; 20: 1509–1518.

Wiedemann HR : Tumors and hemihypertrophy associated with Wiedemann–Beckwith syndrome. Eur J Pediatr 1983; 141: 129.

Gaston V, Le Bouc Y, Soupre V et al: Analysis of the methylation status of the KCNQ1OT and H19 genes in leukocyte DNA for the diagnosis and prognosis of Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 2001; 9: 409–418.

Ward A, Dutton JR : Regulation of the Wilms’ tumour suppressor (WT1) gene by an antisense RNA: a link with genomic imprinting? J Pathol 1998; 185: 342–344.

Moorwood K, Charles AK, Salpekar A, Wallace JI, Brown KW, Malik K : Antisense WT1 transcription parallels sense mRNA and protein expresssion in foetal kidney and can elevate protein levels in vitro. J Pathol 1998; 185: 352–359.

Malik K, Salpekar A, Hancock A et al: Identification of differential methylation of the WT1 antisense regulatory region and relaxation of imprinting in Wilms’ tumor. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 2356–2360.

Malik KT, Wallace JI, Ivins SM, Brown KW : Identification of an antisense WT1 promoter in intron 1: implications for WT1 gene regulation. Oncogene 1995; 11: 1589–1595.

Martin RA, Grange DK, Zehnbauer B, Debaun MR : LIT1 and H19 methylation defects in isolated hemihyperplasia. Am J Med Genet 2005; 134: 129–131.

Craft AW, Parker L, Stiller C, Cole M : Screening for Wilms-tumor in patients with aniridia, Beckwith–Syndrome, or hemihypertrophy. Med Pediatr Oncol 1995; 24: 231–234.

Choyke PL, Siegel MJ, Craft AW, Green DM, DeBaun MR : Screening for Wilms tumor in children with Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome or idiopathic hemihypertrophy. Med Pediatr Oncol 1999; 32: 196–200.

Moulton T, Crenshaw T, Hao Y et al: Epigenetic lesions at the H19 locus in Wilms-tumor patients. Nat Genet 1994; 7: 440–447.

Ogawa O, Eccles MR, Szeto J et al: Relaxation of insulin-like growth factor II gene imprinting implicated in Wilms’ tumour. Nature 1993; 362: 749–751.

Dallosso AR, Hancock AL, Brown KW, Williams AC, Jackson S, Malik K : Genomic imprinting at the WT1 gene involves a novel coding transcript (AWT1) that shows deregulation in Wilms’ tumours. Hum Mol Genet 2004; 13: 405–415.

Sun F-L, Dean WL, Kelsey G, Allen ND, Reik W : Transactivation of Igf2 in a mouse model of Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Nature 1997; 389: 809–815.

Yan Y, Lee M, Massague J, Barbacid M : Ablation of the CDK inhibitor p57(Kip2) results in increased apoptosis and delayed differentiation during mouse development. Genes Dev 1997; 11: 973–983.

Zhang P, Liégeois NJ, Wong C et al: Altered cell differentiation and proliferation in mice lacking p57KIP2 indicates a role in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Nature 1997; 387: 151–158.

Acknowledgements

We thank the many referring clinicians and the patients and their families for their help with this study. We thank SPARKS and the MRC for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cooper, W., Luharia, A., Evans, G. et al. Molecular subtypes and phenotypic expression of Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 13, 1025–1032 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201463

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201463

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Ultrasonographic characteristics, genetic features, and maternal and fetal outcomes in fetuses with omphalocele in China: a single tertiary center study

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2023)

-

Male Factors: the Role of Sperm in Preimplantation Embryo Quality

Reproductive Sciences (2021)

-

Cancer incidence and spectrum among children with genetically confirmed Beckwith-Wiedemann spectrum in Germany: a retrospective cohort study

British Journal of Cancer (2020)

-

The genetic changes of Wilms tumour

Nature Reviews Nephrology (2019)

-

The effectiveness of Wilms tumor screening in Beckwith–Wiedemann spectrum

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2019)