Abstract

Biological soil crusts (BSC) are the dominant functional vegetation unit in some of the harshest habitats in the world. We assessed BSC response to stress through changes in biotic composition, CO2 gas exchange and carbon allocation in three lichen-dominated BSC from habitats with different stress levels, two more extreme sites in Antarctica and one moderate site in Germany. Maximal net photosynthesis (NP) was identical, whereas the water content to achieve maximal NP was substantially lower in the Antarctic sites, this apparently being achieved by changes in biomass allocation. Optimal NP temperatures reflected local climate. The Antarctic BSC allocated fixed carbon (tracked using 14CO2) mostly to the alcohol soluble pool (low-molecular weight sugars, sugar alcohols), which has an important role in desiccation and freezing resistance and antioxidant protection. In contrast, BSC at the moderate site showed greater carbon allocation into the polysaccharide pool, indicating a tendency towards growth. The results indicate that the BSC of the more stressed Antarctic sites emphasise survival rather than growth. Changes in BSC are adaptive and at multiple levels and we identify benefits and risks attached to changing life traits, as well as describing the ecophysiological mechanisms that underlie them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

Baur A, Baur B, Fröberg L . (1994). Herbivory on calcicolous lichens: different food preferences and growth rates in two co-existing land snails. Oecologia 98: 313–319.

Belnap J, Büdel B, Lange OL . (2003a). Biological soil crusts: characteristics and distribution. In: Belnap J, Lange OL, (eds) Biological soil crusts: structure, function, and management. Ecological Studies Vol. 150 2nd edn Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 3–30.

Belnap J, Prasse R, Harper KT . (2003b). Influence of biological soil crusts on soil environment and vascular plants. In: Belnap J, Lange OL (eds) Biological soil crusts: structure, function, and management. Ecological Studies Vol. 150, 2nd edn. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 281–302.

Bewley JD, Krochko JE . (1982). Desiccation-Tolerance. In: Lange OL, Nobel PS, Osmond CB, Ziegler H, (eds) Physiological Plant Ecology 2, Water relations and carbon assimilation, Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology. Springer: Berlin, pp 325–378.

Brodo IM, Sharnoff SD, Sharnoff S . (2001). Psora. In: Brodo IM, Sharnoff SD, Láurie-Borque S, (eds) Lichens of North America. Yale University Press: New Haven, pp 597–604.

Brown DH, Snelgar WP, Green TGA . (1981). Effects of storage conditions on lichen respiration and desiccation sensitivity. Ann Bot 48: 923–926.

Büdel B . (2003). Biological soil crusts of European temperate and Mediterranean regions. In: Belnap J, Lange OL, (eds) Biological soil crusts: structure, function, and management. Ecological Studies Vol. 150, 2nd edn. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 75–87.

Büdel B, Darienko T, Deutschewitz K, Dojani S, Friedl T, Mohr K et al. (2009). Southern african biological soil crusts are ubiquitous and highly diverse in drylands, being restricted by rainfall frequency. Microb Ecol 57: 229–247.

Büdel B, Vivas M, Lange OL . (2013). Lichen species dominance and the resulting photosynthetic behavior of Sonoran Desert soil crust types (Baja California, Mexico). Ecol Proc 2: 6–15.

Campbell SE . (1979). Soil stabilization by prokaryotic desert crust: implications for precambrian land biota. Orig Life 9: 335–348.

Cannone N, Convey P, Guglielmin M . (2013). Diversity trends of bryophytes in continental Antarctica. Polar Biol 36: 259–271.

Carosi R, Giacomini F, Talarico F, Stump E . (2007). Geology of the Byrd Glacier Discontinuity (Ross Orogen): New survey data from the Britannia Range, Antarctica. Related Publications from ANDRILL Affiliates. Paper 19, http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/andrillaffiliates/19.

Cary CS, McDonald IR, Barrett JE, Cowan DA . (2010). On the rocks: the microbiology of Antarctic Dry Valley soils. Nat Rev 8: 129–138.

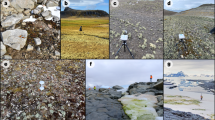

Colesie C, Gommeaux M, Green TGA, Büdel B . (2013). Biological soil crusts in continental Antarctica: Garwood Valley, southern Victoria Land, and Diamond Hill, Darwin Mountains region. Anta Sci 26: 115–123.

Cowan DA, Green TGA, Wilson AT . (1979). Lichen metabolism 1. The use of tritium labeled water in studies of anhydrobiotic metabolism in Ramalina celastri and Peltigera polydactyla. New Phytol 82: 489–503.

Del Prado R, Sancho LG . (2007). Dew as a key factor for the distribution pattern of the lichen species Teloschistes lacunosus in the Tabernas Desert (Spain). Flora 202: 417–428.

Demetras NJ, Hogg ID, Banks JC, Adams BJ . (2010). Latitudinal distribution and mitochondrial DNA (COI) variability of Stereotydeus spp. (Acari: Prostigmata) in Victoria Land and the central Transantarctic Mountains. Anta Sci 22: 749–756.

Domaschke S, Vivas M, Sancho LG, Printzen C . (2013). Ecophysiology and genetic structure of polar versus temperate populations of the lichen Cetraria aculeata. Oecologia 173: 699–709.

Dudley SA, Lechowicz MJ . (1987). Losses of polyol through leaching in subarctic lichens. Plant Physiol 83: 813–815.

Elbert W, Weber B, Burrows S, Steinkamp J, Büdel B, Andrae B et al. (2012). Contribution of crypotogamic covers to the global cycles of carbon and nitrogen. Nat Geosci 5: 459–462.

Farrar JF . (1978). Ecological physiology of the lichen Hypogymnia physodes, 4. Carbon allocation at low temperatures; New Phytol 81: 65–69.

Green TGA . (2008). Lichens in arctic, antarctic and alpine ecosystems. In: Beck A, Lange OL, (eds) Die ökologische Rolle der Flechten. Rundgespräche der Kommission für Ökologie 36, Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil: München, pp 45–66.

Green TGA, Smith DC . (1974). Lichen Physiology: 14. Differences between lichen algae in symbiosis and in isolation. New Phytol 73: 753–766.

Green TGA, Büdel B, Meyer A, Zellner H, Lange OL . (1997). Temperate rainforest lichens in New Zealand: light response of photosynthesis. New Zeal J Bot 35: 493–504.

Green TGA, Nash T-H III, Lange OL . (2008). Physiological ecology of carbon dioxide exchange. In: Nash T-H III, (ed) Lichen biology 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, pp 152–181.

Green TGA, Sancho LG, Pintado A . (2011). Ecophysiology of Desiccation/Rehydration Cycles in Mosses and Lichens. In Lüttge U, Beck E, Barthels D, (eds) Plant Desiccation Tolerance. Ecological Studies 215. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 89–116.

Grime JP . (2002) Plant strategies, vegetation processes and ecosystem properties Second edition John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: West Sussex.

Grime JP, Pierce S . (2012) The evolutionary strategies that shape ecosystems. Wiley-Blackwell: West Sussex.

Grube M, Cardinale M, de Castro JV, Müller H, Berg G . (2009). Species-specific structural and functional diversity of bacterial communities in lichen symbiosis. ISME J 3: 1105–1115.

Herms DA, Mattson WJ . (1992). The dilemma of plants: to grow or to defend. Q Ref Biol 67: 283–335.

Heber U, Lüttge U . (2011). Lichens and Bryophytes: light stress and photoinhibition in desiccation/rehydration cycles – mechanisms of photoprotection. In: Lüttge U, Beck E, Barthels D, (eds) Plant Desiccation Tolerance. Ecological Studies 215. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 212–317.

Honegger R . (2008). The impact of different long-term storage conditions on the viability of lichen forming Ascomycetes and their green algal photobiont, Trebouxia spp. Plant Biol 5: 324–330.

Hovenden MJ, Jackson AE, Seppelt RD . (1994). Field photosynthetic activity of lichens in the Windmill Islands oasis, Wilkes Land, continental Antarctica. Phys Plant 90: 567–576.

Kappen L . (1973). Response to extreme environments – extreme habitats of lichens. In: Ahmadjian V, Hale ME, (eds) The Lichens. Academic press: London, pp 311–380.

Kappen L . (1993). Plant activity under snow and ice, with particular reference to lichens. Arctic 46: 297–302.

Körner C . (2003) Alpine plant life 2nd edn. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, New York.

Kranner I, Cram WJ, Zorn M, Wornik S, Yoshimura I, Stabentheiner E et al. (2005). Antioxidants and photoprotection in a lichen as compared with its isolated symbiotic partners. PNAS 102: 3141–3146.

Kranner I, Beckett R, Hochman A, Nash T-H III . (2008). Desiccation-tolerance in lichens: a review. Bryologist 111: 576–593.

Lange OL, Kilian E . (1985). Reaktivierung der Photosynthese trockener Flechten durch Wasserdampfaufnahme aus dem Luftraum: artspezifisch unterschiedliches Verhalten. Flora 176: 7–23.

Lange OL, Kilian E, Ziegler H . (1986). Water vapor uptake and photosynthesis of lichens: Performance differences in species with green and blue-green algae as phycobionts. Oecologia 71: 104–110.

Lange OL, Meyer A, Zellner H, Heber U . (1994). Photosynthesis and water relations of lichen soil crusts: field measurements in the coastal fog zone of the Namib Desert. Funct ecol 8: 253–264.

Lange OL, Green TGA . (2005). Lichens show that fungi can acclimate their respiration to seasonal changes in temperature. Oecologia 142: 11–19.

Lange OL, Green TGA, Melzer B, Meyer A, Zellner H . (2006). Water relations and CO2 exchange of the terrestrial lichen Teloschistes capensis in the Namib fog desert: Measurements during two seasons in the field and under controlled conditions. Flora 201: 268–280.

Melick DR, Seppelt RD . (1992). Loss of soluble carbohydrates and changes in freezing point of Antarctic bryophytes after leaching and repated freeze-thaw cycles. Anta Sci 4: 399–404.

Nash T-H III, White SL, Marsh JE . (1977). Lichen and moss distribution and biomass in hot desert ecosystems. Bryologist 80: 470–479.

Øvstedal DO, Smith RIL . (2001) Lichens of Antarctica and South Georgia. A guide to their identification and ecology. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Palmquist K, Dahlman L, Valladares F . (2002). CO2 exchange and thallus nitrogen across 75 contrasting lichens associations from different climate zones. Oecologia 13: 295–306.

Palmquist K, Dahlman L, Jonsson A, Nash T-H III . (2008). In: Nash T-H III, (ed) Lichen Biology 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press: New York, pp 183–221.

Pannewitz S, Schlensog M, Green TGA, Sancho LG, Schroeter B . (2003). Are lichens active under snow in continental Antarctica? Oecologia 135: 30–38.

Pardow A, Hartard B, Lakatos M . (2010). Morphological, photosynthetic and water relations traits underpin the contrasting success of two lichen groups at the interior and edge forest fragments. AoB Plants, (2010). plq004.

Pointing SB, Belnap J . (2012). Microbial colonization and controls in dryland systems. Nat Rev Microbiol 10: 551–562.

Poorter H, Niklas KJ, Reich PB, Oleksyn J, Poot P, Mommer L . (2012). Biomass allocation to leaves, stems and roots: meta-analysis of interspecific variation and environmental control. New Phytol 193: 30–50.

Reynolds JF, Stafford-Smith DM . (2002) Global Desertification: Do Humans Cause Deserts? Dahlem Workshop Report 88. Dahlem University Press: Berlin.

Richardson DHS, Smith DC . (1968). Lichen physiology; 9: Carbohydrate movement from the Trebouxia symbiont of Xanthoria aureola to the fungus. New Phytol 67: 61–68.

Roser DJ, Melick DR, Ling HU, Seppelt RD . (1992). Polyol and sugar content of terrestrial plants from continental Antarctica. Anta Sci 4: 413–420.

Sancho LG, Green TGA, Pintado A . (2007). Slowest to fastest: extreme range in lichen growth rates supports their use as an indicator of climate change in Antarctica. Flora 202: 667–673.

Schroeter B, Scheidegger C . (1995). Water relations in lichens at subzero temperatures: structural changes and carbon dioxide exchange in the lichen Umbilicaria aprina from continental Antarctica. New Phytol 131: 273–285.

Schroeter B, Green TGA, Pannewitz S, Schlensog M, Sancho LG . (2010). Fourteen degrees of latitude and a continent apart: comparison of lichen activity over two years at continental and maritime Antarctic sites. Anta Sci 22: 681–690.

Singh R, Ranjan S, Nayaka S, Pathre UV, Shirke PA . (2013). Functional characteristics of a fruticose type of lichen, Stereocaulon foliosum Nyl. in response to light and water stress. Acta Physiol Plant 5: 1605–1615.

Søchting U, Castello M . (2012). The polar lichens Caloplaca darbishirei and C. soropelta highlight the direction of bipolar migration. Polar Biol 35: 1143–1149.

Storey BC, Fink D, Hood D, Joy K, Shulmeister J, Riger-Kusk M et al. (2010). Cosmogenic nuclide exposure age constraints on the glacial history of the Lake Wellman area, Darwin Mountains, Antarctica. Anta Sci 22: 603–618.

Tearle PV . (1987). Cryptogamic carbohydrate release and microbial response during spring freeze-thaw cycles in Antarctic fellfield fines. Soil Biol Biochem 19: 381–390.

Warren-Rhodes KA, Rhodes KL, Pointing SB, Ewing SA, Lacap DC, Gómez-Silva B et al. (2006). Hypolithic cyanobacteria, dry limit of photosynthesis, and microbial ecology in the hyperarid Atacama Desert. Microb Ecol 52: 389–398.

Wynn-Williams DD, Holder JM, Edwards HGM . (2000). Lichens at the limits of life: past perspectives and modern technology. In Schroeter B, Schlensog M, Green TGA, (eds) New aspects in cryptogamic research. Cramer: Berlin, pp 275–288.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Antarctica New Zealand (AntNZ) for logistical support over several years as part of the Latitudinal Gradient Project coordinated by Shulamit Gordon. Logistics support was also provided by the Australian Antarctic Program, the Spanish National Antarctic Program and the US Coastguard Reserve. They are all gratefully thanked. The New Zealand Foundation for Research, Science and Technology (FRST), the University of Waikato Vice Chancellor’s Fund and the Department of Biological Sciences, University of Waikato provided financial support. The research was supported by the FRST grant, ‘Understanding, valuing and protecting Antarctica’s unique terrestrial ecosystems: predicting biocomplexity in Dry Valley ecosystems’ and TGAG by the Spanish Education Ministry grants POL2006-08405 and CTM2009-12838-C04-01. BB and CC acknowledge the DFG Schwerpunktprogramm 1158 (BU 666/11-1). Part of the research were also funded by the ERA-Net BiodivERsA program, with the national funders German Research Foundation (DFG), Austrian Science Fund (FWF), The Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning (FORMAS), and the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (MINECO), part of the 2010-2011 BiodivERsA joint call. We thank Professor Neuhaus (TU Kl) for logistic support in the isotope laboratory.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Colesie, C., Allan Green, T., Haferkamp, I. et al. Habitat stress initiates changes in composition, CO2 gas exchange and C-allocation as life traits in biological soil crusts. ISME J 8, 2104–2115 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.47

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.47

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Changes in Microbial Composition During the Succession of Biological Soil Crusts in Alpine Hulun Buir Sandy Land, China

Microbial Ecology (2024)

-

Summer activity patterns for a moss and lichen in the maritime Antarctic with respect to altitude

Polar Biology (2021)

-

Ecophysiological properties of three biological soil crust types and their photoautotrophs from the Succulent Karoo, South Africa

Plant and Soil (2018)

-

Environmental determinants of biocrust carbon fluxes across Europe: possibilities for a functional type approach

Plant and Soil (2018)

-

Biological soil crusts of Arctic Svalbard and of Livingston Island, Antarctica

Polar Biology (2017)