Abstract

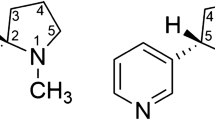

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has the authority to regulate cigarette smoke constituents, and a reduction in nicotine content might benefit public health by reducing the prevalence of smoking. Research suggests that cigarette smoke constituents that inhibit monoamine oxidase (MAO) may increase the reinforcing value of low doses of nicotine. The aim of the present experiments was to further characterize the impact of MAO inhibition on the primary reinforcing and reinforcement enhancing effects of nicotine in rats. In a series of experiments, rats responded for intravenous nicotine infusions or a moderately-reinforcing visual stimulus in daily 1-h sessions. Rats received pre-session injections of known MAO inhibitors. The results show that (1) tranylcypromine (TCP), a known MAO inhibitor, increases sensitivity to the primary reinforcing effects of nicotine, shifting the dose-response curve for nicotine to the left, (2) inhibition of MAO-A, but not MAO-B, increases low-dose nicotine self-administration, (3) partial MAO-A inhibition, to the degree observed in chronic cigarette smokers, also increases low-dose nicotine self-administration, and (4) TCP decreases the threshold nicotine dose required for reinforcement enhancement. The results of the present experiments suggest cigarette smoke constituents that inhibit MAO-A, in the range seen in chronic smokers, are likely to increase the primary reinforcing and reinforcement enhancing effects of low doses of nicotine. If the FDA reduces the nicotine content of cigarettes, then variability in constituents that inhibit MAO-A could impact smoking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

Arnold MM, Loughlin SE, Belluzzi JD, Leslie FM (2014). Reinforcing and neural activating effects of norharmane, a non-nicotine tobacco constituent, alone and in combination with nicotine. Neuropharmacology 85: 293–304.

Bardo MT, Green TA, Crooks PA, Dwoskin LP (1999). Nornicotine is self-administered intravenously by rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 146: 290–296.

Belluzzi JD, Wang R, Leslie FM (2005). Acetaldehyde enhances acquisition of nicotine self-administration in adolescent rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 30: 705–712.

Benowitz NL, Henningfield JE (1994). Establishing a nicotine threshold for addiction. The implications for tobacco regulation. N Engl J Med 331: 123–125.

Brennan KA, Crowther A, Putt F, Roper V, Waterhouse U, Truman P (2015). Tobacco particulate matter self-administration in rats: differential effects of tobacco type. Addict Biol 20: 227–235.

Buffalari DM, Marfo NY, Smith TT, Levin ME, Weaver MT, Thiels E et al (2014). Nicotine enhances the expression of a sucrose or cocaine conditioned place preference in adult male rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 124: 320–325.

Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Palmatier MI, Liu X, Chaudhri N, Sved AF (2009). The role of nicotine in smoking: a dual-reinforcement model. Nebr Symp Motiv 55: 91–109.

Clemens KJ, Caille S, Stinus L, Cador M (2009). The addition of five minor tobacco alkaloids increases nicotine-induced hyperactivity, sensitization and intravenous self-administration in rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 12: 1355–1366.

Costello MR, Reynaga DD, Mojica CY, Zaveri NT, Belluzzi JD, Leslie FM (2014). Comparison of the reinforcing properties of nicotine and cigarette smoke extract in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 39: 1843–1851.

Depootere R, Li D, Lane J, Emmett-Oglesby M (1993). Parameters of self-administration of cocaine in rats under a progressive-ratio schedule. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 45: 539–548.

Donny EC, Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Evans-Martin FF, Booth S, Gharib MA et al (2003). Operant responding for a visual reinforcer in rats is enhanced by noncontingent nicotine: implications for nicotine self-administration and reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 169: 68–76.

Donny EC, Denlinger RL, Tidey JW, Koopmeiners JS, Benowitz NL, Vandrey RG et al (2015). Randomized trial of reduced-nicotine standards for cigarettes. N Engl J Med 373: 1340–1349.

Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Pappas N, Logan J, MacGregor R et al (1996a). Inhibition of monoamine oxidase B in the brains of smokers. Nature 379: 733–736.

Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Pappas N, Logan J, Shea C et al (1996b). Brain monoamine oxidase A inhibition in cigarette smokers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 14065–14069.

Guillem K, Vouillac C, Azar MR, Parsons LH, Koob GF, Cador M et al (2005). Monoamine oxidase inhibition dramatically increases the motivation to self-administer nicotine in rats. J Neurosci 25: 8593–8600.

Guillem K, Vouillac C, Azar MR, Parsons LH, Koob GF, Cador M et al (2006). Monoamine oxidase A rather than monoamine oxidase B inhibition increases nicotine reinforcement in rats. Eur J Neurosci 24: 3532–3540.

Hatsukami DK, Perkins KA, Lesage MG, Ashley DL, Henningfield JE, Benowitz NL et al (2010). Nicotine reduction revisited: science and future directions. Tob Control 19: e1–10.

Inaba-Hasegawa K, Akao Y, Maruyama W, Naoi M (2013). Rasagiline and selegiline, inhibitors of type B monoamine oxidase, induce Type A monoamine oxidase in human SH-SY5Y cells. J Neural Transm 120: 435–444.

Lewis AJ, Truman P, Hosking MR, Miller JH (2012). Monoamine oxidase inhibitory activity in tobacco smoke varies with tobacco type. Tob Control 21: 39–43.

Lotfipour S, Arnold MM, Hogenkamp DJ, Gee KW, Belluzzi JD, Leslie FM (2011). The monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitor tranylcypromine enhances nicotine self-administration in rats through a mechanism independent of MAO inhibition. Neuropharmacology 61: 95–104.

Murphy SE, Park SS, Thompson EF, Wilkens LR, Patel Y, Stram DO et al (2014). Nicotine N-glucuronidation relative to N-oxidation and C-oxidation and UGT2B10 genotype in five ethnic/racial groups. Carcinogenesis 35: 2526–2533.

Palmatier MI, Coddington SB, Liu X, Donny EC, Caggiula AR, Sved AF (2008). The motivation to obtain nicotine-conditioned reinforcers depends on nicotine dose. Neuropharmacology 55: 1425–1430.

Palmatier MI, Evans-Martin FF, Hoffman A, Caggiula AR, Chaudhri N, Donny EC et al (2006). Dissociating the primary reinforcing and reinforcement-enhancing effects of nicotine using a rat self-administration paradigm with concurrently available drug and environmental reinforcers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 184: 391–400.

Palmatier MI, Liu X, Matteson GL, Donny EC, Caggiula AR, Sved AF (2007). Conditioned reinforcement in rats established with self-administered nicotine and enhanced by noncontingent nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 195: 235–243.

Rodgman A, Perfetti TA (2013) The Chemical Components of Tobacco and Tobacco Smoke 2nd edn. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA.

Rupprecht LE, Smith TT, Schassburger RL, Buffalari DM, Sved AF, Donny EC (2015). Behavioral mechanisms underlying nicotine reinforcement. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 24: 19–53.

Smith TT, Levin ME, Schassburger RL, Buffalari DM, Sved AF, Donny EC (2013). Gradual and immediate nicotine reduction result in similar low-dose nicotine self-administration. Nicotine Tob Res 15: 1918–1925.

Smith TT, Schaff MB, Rupprecht LE, Schassburger RL, Buffalari DM, Murphy SE et al (2015). Effects of MAO inhibition and a combination of minor alkaloids, beta-carbolines, and acetaldehyde on nicotine self-administration in adult male rats. Drug Alcohol Depend 155: 243–252.

U.S. Congress (2009). Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (H.R. 1256). Available at: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/111/hr1256/text. Accessed 23 February 2016.

Villegier AS, Belluzzi JD, Leslie FM (2011). Serotonergic mechanism underlying tranylcypromine enhancement of nicotine self-administration. Synapse 65: 479–489.

Villegier AS, Blanc G, Glowinski J, Tassin JP (2003). Transient behavioral sensitization to nicotine becomes long-lasting with monoamine oxidases inhibitors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 76: 267–274.

Villegier AS, Lotfipour S, McQuown SC, Belluzzi JD, Leslie FM (2007). Tranylcypromine enhancement of nicotine self-administration. Neuropharmacology 52: 1415–1425.

Villegier AS, Salomon L, Granon S, Changeux JP, Belluzzi JD, Leslie FM et al (2006). Monoamine oxidase inhibitors allow locomotor and rewarding responses to nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology 31: 1704–1713.

Weaver MT, Geier CF, Levin ME, Caggiula AR, Sved AF, Donny EC (2012). Adolescent exposure to nicotine results in reinforcement enhancement but does not affect adult responding in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend 125: 307–312.

Wing VC, Shoaib M (2010). A second-order schedule of food reinforcement in rats to examine the role of CB1 receptors in the reinforcement-enhancing effects of nicotine. Addict Biol 15: 380–392.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Joshua Alberts, Samuel Gutherz, Emily Pitzer, and Elizabeth Shupe for their extensive help in conducting experimental sessions. Thanks to undergraduates in the laboratory including E Corina Andriescu, Kayla Convry, Dora Danko, Mackenzie Meixner, Jessica Pelland, Hangil Seo, Nicole Silva, Isha Vasudeva, and Marisa Wallas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, T., Rupprecht, L., Cwalina, S. et al. Effects of Monoamine Oxidase Inhibition on the Reinforcing Properties of Low-Dose Nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacol 41, 2335–2343 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2016.36

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2016.36

This article is cited by

-

Tabakentwöhnung

MMW - Fortschritte der Medizin (2020)

-

The nicotine-degrading enzyme NicA2 reduces nicotine levels in blood, nicotine distribution to brain, and nicotine discrimination and reinforcement in rats

BMC Biotechnology (2018)

-

Reduced-Nicotine Cigarettes in Young Smokers: Impact of Nicotine Metabolism on Nicotine Dose Effects

Neuropsychopharmacology (2017)