Abstract

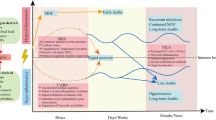

For more than two decades, sepsis was defined as a microbial infection that produces fever (or hypothermia), tachycardia, tachypnoea and blood leukocyte changes. Sepsis is now increasingly being considered a dysregulated systemic inflammatory and immune response to microbial invasion that produces organ injury for which mortality rates are declining to 15–25%. Septic shock remains defined as sepsis with hyperlactataemia and concurrent hypotension requiring vasopressor therapy, with in-hospital mortality rates approaching 30–50%. With earlier recognition and more compliance to best practices, sepsis has become less of an immediate life-threatening disorder and more of a long-term chronic critical illness, often associated with prolonged inflammation, immune suppression, organ injury and lean tissue wasting. Furthermore, patients who survive sepsis have continuing risk of mortality after discharge, as well as long-term cognitive and functional deficits. Earlier recognition and improved implementation of best practices have reduced in-hospital mortality, but results from the use of immunomodulatory agents to date have been disappointing. Similarly, no biomarker can definitely diagnose sepsis or predict its clinical outcome. Because of its complexity, improvements in sepsis outcomes are likely to continue to be slow and incremental.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 1 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $119.00 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Majno, G. The ancient riddle of σηψιζ (sepsis). J. Infect. Dis. 163, 937–945 (1991).

Bone, R. C., Sibbald, W. J. & Sprung, C. L. The ACCP-SCCM consensus conference on sepsis and organ failure. Chest 101, 1481–1483 (1992). This paper has laid the ground for our current understanding of sepsis by underlining the crucial role of the host response to infection for which the term SIRS was coined. Furthermore, it was pointed out that SIRS can also result from non-infectious causes.

Levy, M. M. et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit. Care Med. 31, 1250–1256 (2003).

Singer, M. et al. The third international consensus conference on sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315, 801–810 (2016). The third consensus update of the definitions and clinical criteria for sepsis and septic shock. Although there has been an important effort to improve the understanding of sepsis, controversy remains as to whether these new criteria will be useful or practical as early warning signs, especially in low-income and middle-income countries where it is often difficult to obtain the required measures of organ injury.

Le, J. M. & Vilcek, J. Interleukin 6: a multifunctional cytokine regulating immune reactions and the acute phase protein response. Lab. Invest. 61, 588–602 (1989).

Dinarello, C. A. Interleukin-1. Rev. Infect. Dis. 6, 51–95 (1984).

Beutler, B. & Cerami, A. The biology of cachectin/TNF — a primary mediator of the host response. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 7, 625–655 (1989).

Matzinger, P. Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 12, 991–1045 (1994).

Deutschman, C. S. & Tracey, K. J. Sepsis: current dogma and new perspectives. Immunity 40, 463–475 (2014).

Levi, M., Schultz, M. & van der Poll, T. Sepsis and thrombosis. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 39, 559–566 (2013).

Opal, S. M. & van der Poll, T. Endothelial barrier dysfunction in septic shock. J. Intern. Med. 277, 277–293 (2015).

White, L. E. et al. Acute kidney injury is surprisingly common and a powerful predictor of mortality in surgical sepsis. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 75, 432–438 (2013).

Kaukonen, K. M., Bailey, M., Suzuki, S., Pilcher, D. & Bellomo, R. Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000–2012. JAMA 311, 1308–1316 (2014). This is a retrospective analysis of an administrative database from >100,000 patients with recorded sepsis or septic shock. Mortality significantly improved in patients with both severe sepsis and septic shock, but did so at rates that were comparable to other diagnoses.

Ferrer, R. et al. Improvement in process of care and outcome after a multicenter severe sepsis educational program in Spain. JAMA 299, 2294–2303 (2008).

Levy, M. M. et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: association between performance metrics and outcomes in a 7.5-year study. Crit. Care Med. 43, 3–12 (2015). This is one of many papers to demonstrate that increasing awareness for sepsis and the initiation of quality improvement initiatives in the field of sepsis can improve patient survival.

Fleischmann, C. et al. Assessment of global incidence and mortality of hospital-treated sepsis — current estimates and limitations. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 193, 259–272 (2016). This population-level epidemiological data from 15 international databases over the past 36 years demonstrate a high level of sepsis incidence in developed countries. By contrast, the study emphasizes the paucity of sepsis data from the developing world.

Jawad, I., Luksic, I. & Rafnsson, S. B. Assessing available information on the burden of sepsis: global estimates of incidence, prevalence and mortality. J. Glob. Health 2, 010404 (2012).

Becker, J. U., Theodosis, C., Jacob, S. T., Wira, C. R. & Groce, N. E. Surviving sepsis in low-income and middle-income countries: new directions for care and research. Lancet Infect. Dis. 9, 577–582 (2009).

Murray, C. J. & Lopez, A. D. Measuring the global burden of disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 448–457 (2013).

Mayanja, B. N. et al. Septicaemia in a population-based HIV clinical cohort in rural Uganda, 1996–2007: incidence, aetiology, antimicrobial drug resistance and impact of antiretroviral therapy. Trop. Med. Int. Health 15, 697–705 (2010).

Gordon, M. A. et al. Bacteraemia and mortality among adult medical admissions in Malawi — predominance of non-typhi salmonellae and Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. 42, 44–49 (2001).

Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386, 743–800 (2015).

van den Boogaard, W., Manzi, M., Harries, A. D. & Reid, A. J. Causes of pediatric mortality and case-fatality rates in eight Medecins Sans Frontieres-supported hospitals in Africa. Public Health Action 2, 117–121 (2012).

Sundararajan, V., Macisaac, C. M., Presneill, J. J., Cade, J. F. & Visvanathan, K. Epidemiology of sepsis in Victoria, Australia. Crit. Care Med. 33, 71–80 (2005).

Seymour, C. W., Iwashyna, T. J., Cooke, C. R., Hough, C. L. & Martin, G. S. Marital status and the epidemiology and outcomes of sepsis. Chest 137, 1289–1296 (2010).

Fleischmann, C. et al. Hospital incidence and mortality rates of sepsis. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 113, 159–166 (2016).

Dombrovskiy, V. Y., Martin, A. A., Sunderram, J. & Paz, H. L. Rapid increase in hospitalization and mortality rates for severe sepsis in the United States: a trend analysis from 1993 to 2003. Crit. Care Med. 35, 1244–1250 (2007).

Martin, G. S., Mannino, D. M., Eaton, S. & Moss, M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1546–1554 (2003).

Liu, V. et al. Hospital deaths in patients with sepsis from 2 independent cohorts. JAMA 312, 90–92 (2014).

Lagu, T. et al. What is the best method for estimating the burden of severe sepsis in the United States? J. Crit. Care 27, 414.e1–414.e9 (2012).

Gaieski, D. F., Edwards, J. M., Kallan, M. J. & Carr, B. G. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit. Care Med. 41, 1167–1174 (2013). The incidence and outcome of sepsis were estimated using four different published methods; depending on the methods of data abstraction, the incidence of sepsis in the United States could vary as much as 3.5-fold.

Rhee, C., Gohil, S. & Klompas, M. Regulatory mandates for sepsis care — reasons for caution. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 1673–1676 (2014).

Whittaker, S. A. et al. Severe sepsis cohorts derived from claims-based strategies appear to be biased toward a more severely ill patient population. Crit. Care Med. 41, 945–953 (2013).

Iwashyna, T. J. & Angus, D. C. Declining case fatality rates for severe sepsis: good data bring good news with ambiguous implications. JAMA 311, 1295–1297 (2014).

McPherson, D. et al. Sepsis-associated mortality in England: an analysis of multiple cause of death data from 2001 to 2010. BMJ Open 3, e002586 (2013).

Vincent, J. L. et al. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit. Care Med. 34, 344–353 (2006).

Takeuchi, O. & Akira, S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell 140, 805–820 (2010).

Tang, D., Kang, R., Coyne, C. B., Zeh, H. J. & Lotze, M. T. PAMPs and DAMPs: signal 0s that spur autophagy and immunity. Immunol. Rev. 249, 158–175 (2012).

Bierhaus, A. & Nawroth, P. P. Modulation of the vascular endothelium during infection — the role of NF-kappa B activation. Contrib. Microbiol. 10, 86–105 (2003).

Parikh, S. M. Dysregulation of the angiopoietin–Tie-2 axis in sepsis and ARDS. Virulence 4, 517–524 (2013).

Guo, R. F. & Ward, P. A. Role of C5a in inflammatory responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23, 821–852 (2005).

Ward, P. A. The harmful role of C5a on innate immunity in sepsis. J. Innate Immun. 2, 439–445 (2010).

Stevens, J. H. et al. Effects of anti-C5a antibodies on the adult respiratory distress syndrome in septic primates. J. Clin. Invest. 77, 1812–1816 (1986).

Czermak, B. J. et al. Protective effects of C5a blockade in sepsis. Nat. Med. 5, 788–792 (1999).

Rittirsch, D. et al. Functional roles for C5a receptors in sepsis. Nat. Med. 14, 551–557 (2008).

Garcia, C. C. et al. Complement C5 activation during influenza A infection in mice contributes to neutrophil recruitment and lung injury. PLoS ONE 8, e64443 (2013).

Sun, S. et al. Inhibition of complement activation alleviates acute lung injury induced by highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus infection. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 49, 221–230 (2013).

Sun, S. et al. Treatment with anti-C5a antibody improves the outcome of H7N9 virus infection in African green monkeys. Clin. Infect. Dis. 60, 586–595 (2015). This paper demonstrates the potential beneficial effects of complement inhibition in a clinically relevant monkey model of viral infection.

US National Library of Medicine. Studying complement inhibition in early, newly developing septic organ dysfunction (SCIENS). ClinicalTrials.govhttp://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02246595 (2014).

Gentile, L. F. et al. Persistent inflammation and immunosuppression: a common syndrome and new horizon for surgical intensive care. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 72, 1491–1501 (2012). This paper provides a description of a phenotype of individuals who survived sepsis or critical illness who exhibit PICS. The authors propose that as early treatments for sepsis and trauma improve, this phenotype will predominate in survivors, especially the elderly.

Hu, D. et al. Persistent inflammation–immunosuppression catabolism syndrome, a common manifestation of patients with enterocutaneous fistula in intensive care unit. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 76, 725–729 (2014).

Vanzant, E. L. et al. Persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome after severe blunt trauma. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 76, 21–29; discussion 29–30 (2014).

Rubartelli, A. & Lotze, M. T. Inside, outside, upside down: damage-associated molecular-pattern molecules (DAMPs) and redox. Trends Immunol. 28, 429–436 (2007).

Walton, A. H. et al. Reactivation of multiple viruses in patients with sepsis. PLoS ONE 9, e98819 (2014).

Kollef, K. E. et al. Predictors of 30-day mortality and hospital costs in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia attributed to potentially antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Chest 134, 281–287 (2008).

Otto, G. P. et al. The late phase of sepsis is characterized by an increased microbiological burden and death rate. Crit. Care 15, R183 (2011). An important publication that documents that the majority of patients with protracted sepsis develop infections with ‘opportunistic-type pathogens’, thereby strongly supporting the concept of sepsis progressing to an immunosuppressive disorder.

Torgersen, C. et al. Macroscopic postmortem findings in 235 surgical intensive care patients with sepsis. Anesth. Analg. 108, 1841–1847 (2009).

Delano, M. J. et al. MyD88-dependent expansion of an immature GR-1+CD11b+ population induces T cell suppression and Th2 polarization in sepsis. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1463–1474 (2007).

Taneja, R., Sharma, A. P., Hallett, M. B., Findlay, G. P. & Morris, M. R. Immature circulating neutrophils in sepsis have impaired phagocytosis and calcium signaling. Shock 30, 618–622 (2008).

Munoz, C. et al. Dysregulation of in vitro cytokine production by monocytes during sepsis. J. Clin. Invest. 88, 1747–1754 (1991).

Cuenca, A. G. et al. A paradoxical role for myeloid-derived suppressor cells in sepsis and trauma. Mol. Med. 17, 281–292 (2011). A study demonstrating that the expansion of MDSCs in sepsis can be associated with the preservation of innate immunity, even in the presence of adaptive immune suppression.

Drifte, G., Dunn-Siegrist, I., Tissieres, P. & Pugin, J. Innate immune functions of immature neutrophils in patients with sepsis and severe systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Crit. Care Med. 41, 820–832 (2013).

Hashiba, M. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in patients with sepsis. J. Surg. Res. 194, 248–254 (2015).

Hynninen, M. et al. Predictive value of monocyte histocompatibility leukocyte antigen-DR expression and plasma interleukin-4 and -10 levels in critically ill patients with sepsis. Shock 20, 1–4 (2003).

Boomer, J. S. et al. Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. JAMA 306, 2594–2605 (2011). This is the first study to show that immune effector cells in tissues from patients dying of sepsis have severe impairment of stimulated cytokine production. This study also demonstrated that ‘T cell exhaustion’ is a likely mechanism that contributes to immunosuppression in patients with sepsis, providing a rationale for the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors as a novel potential therapy.

Meakins, J. L. et al. Delayed hypersensitivity: indicator of acquired failure of host defenses in sepsis and trauma. Ann. Surg. 186, 241–250 (1977).

Hotchkiss, R. S. et al. Apoptotic cell death in patients with sepsis, shock, and multiple organ dysfunction. Crit. Care Med. 27, 1230–1251 (1999). This is the first study to show that patients with sepsis develop profound loss of immune effector cells via apoptosis, establishing that sepsis-induced apoptosis is a major immunosuppressive mechanism in sepsis.

Hotchkiss, R. S. et al. Prevention of lymphocyte cell death in sepsis improves survival in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 14541–14546 (1999). This paper encourages more research on immune augmentatory approaches in sepsis.

Drewry, A. M. et al. Persistent lymphopenia after diagnosis of sepsis predicts mortality. Shock 42, 383–391 (2014). This is a study that demonstrated that a sustained low total lymphocyte count was associated with increased mortality. Although the mechanisms are unclear, the data reveal that a commonly obtained clinical measurement can identify the severity of sepsis and organ failure.

Coopersmith, C. M. et al. Antibiotics improve survival and alter the inflammatory profile in a murine model of sepsis from Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Shock 19, 408–414 (2003).

Bommhardt, U. et al. Akt decreases lymphocyte apoptosis and improves survival in sepsis. J. Immunol. 172, 7583–7591 (2004).

Hotchkiss, R. S. et al. Caspase inhibitors improve survival in sepsis: a critical role of the lymphocyte. Nat. Immunol. 1, 496–501 (2000).

Hotchkiss, R. S. et al. TAT-BH4 and TAT-Bcl-xL peptides protect against sepsis-induced lymphocyte apoptosis in vivo. J. Immunol. 176, 5471–5477 (2006).

Hotchkiss, R. S. et al. Overexpression of Bcl-2 in transgenic mice decreases apoptosis and improves survival in sepsis. J. Immunol. 162, 4148–4156 (1999).

Schwulst, S. J. et al. Agonistic monoclonal antibody against CD40 receptor decreases lymphocyte apoptosis and improves survival in sepsis. J. Immunol. 177, 557–565 (2006).

Schwulst, S. J. et al. Bim siRNA decreases lymphocyte apoptosis and improves survival in sepsis. Shock 30, 127–134 (2008).

Angus, D. C. & van der Poll, T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 840–851 (2013). This review provides a concise update of what was known at the time and what has become a very prescient appraisal of the future of sepsis research.

Chelazzi, C., Villa, G., Mancinelli, P., De Gaudio, A. R. & Adembri, C. Glycocalyx and sepsis-induced alterations in vascular permeability. Crit. Care 19, 26 (2015).

London, N. R. et al. Targeting Robo4-dependent Slit signaling to survive the cytokine storm in sepsis and influenza. Sci. Transl Med. 2, 23ra19 (2010).

Karpman, D. et al. Complement interactions with blood cells, endothelial cells and microvesicles in thrombotic and inflammatory conditions. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 865, 19–42 (2015).

Zecher, D., Cumpelik, A. & Schifferli, J. A. Erythrocyte-derived microvesicles amplify systemic inflammation by thrombin-dependent activation of complement. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 34, 313–320 (2014).

Riewald, M. & Ruf, W. Science review: role of coagulation protease cascades in sepsis. Crit. Care 7, 123–129 (2003).

Shorr, A. F. et al. Protein C concentrations in severe sepsis: an early directional change in plasma levels predicts outcome. Crit. Care 10, R92 (2006).

Matsumoto, H. et al. Enhanced expression of cell-specific surface antigens on endothelial microparticles in sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation. Shock 43, 443–449 (2015).

Aird, W. C. The role of the endothelium in severe sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Blood 101, 3765–3777 (2003).

Levi, M. & van der Poll, T. Inflammation and coagulation. Crit. Care Med. 38, S26–34 (2010).

Sato, R. & Nasu, M. A review of sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy. J. Intensive Care 3, 48 (2015).

Galley, H. F. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in sepsis. Br. J. Anaesth. 107, 57–64 (2011).

Nizet, V. & Johnson, R. S. Interdependence of hypoxic and innate immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 609–617 (2009).

Ricci, Z., Polito, A., Polito, A. & Ronco, C. The implications and management of septic acute kidney injury. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 7, 218–225 (2011).

Angus, D. C. et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit. Care Med. 29, 1303–1310 (2001).

Watanabe, E. et al. Sepsis induces extensive autophagic vacuolization in hepatocytes: a clinical and laboratory-based study. Lab. Invest. 89, 549–561 (2009).

Scerbo, M. H. et al. Beyond blood culture and gram stain analysis: a review of molecular techniques for the early detection of bacteremia in surgical patients. Surg. Infect. (Larchmt) 17, 294–302 (2016).

Vincent, J. L., Opal, S. M., Marshall, J. C. & Tracey, K. J. Sepsis definitions: time for change. Lancet 381, 774–775 (2013). A plea to abandon the SIRS criteria and return to the meaning of ‘sepsis’ to common, everyday language — a ‘bad infection’ with some degree of organ dysfunction.

Seymour, C. W. et al. Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis: for the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315, 762–774 (2016). This review of 1.3 million electronic health records and validation with another 700,000 records identified Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) and quick SOFA (qSOFA) scores as valuable tools to predict in-hospital mortality. The qSOFA was most predictive outside the ICU, suggesting that it might be useful as a ‘prompt’ to consider sepsis in early warning systems.

Shankar-Hari, M. et al. Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: for the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315, 775–787 (2016). This systematic review of 166,479 patients with defined septic shock has revealed a working consensus definition of septic shock as hypotension requiring vasopressor support to maintain a mean arterial blood pressure of >65 mmHg and a plasma lactate level of >2 mmol per l with adequate resuscitation.

Casserly, B. et al. Lactate measurements in sepsis-induced tissue hypoperfusion: results from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign database. Crit. Care Med. 43, 567–573 (2015).

Rowland, T., Hilliard, H. & Barlow, G. Procalcitonin: potential role in diagnosis and management of sepsis. Adv. Clin. Chem. 68, 71–86 (2015).

Bloos, F. & Reinhart, K. Rapid diagnosis of sepsis. Virulence 5, 154–160 (2014).

de Jong, E. et al. Efficacy and safety of procalcitonin guidance in reducing the duration of antibiotic treatment in critically ill patients: a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00053-0 (2016). This randomized controlled trial from 15 institutions in the Netherlands demonstrated that using procalcitonin concentrations to dictate antibiotic cessation reduced antibiotic duration by 2 days and reduced in-hospital mortality.

Westwood, M. et al. Procalcitonin testing to guide antibiotic therapy for the treatment of sepsis in intensive care settings and for suspected bacterial infection in emergency department settings: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol. Assess. 19, 1–236 (2015).

Schuetz, P. et al. Procalcitonin to initiate or discontinue antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9, CD007498 (2012).

O'Grady, N. P. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52, e162–e193 (2011).

Kumar, A. et al. Initiation of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy results in a fivefold reduction of survival in human septic shock. Chest 136, 1237–1248 (2009).

Zahar, J. R. et al. Outcomes in severe sepsis and patients with septic shock: pathogen species and infection sites are not associated with mortality. Crit. Care Med. 39, 1886–1895 (2011).

Kumar, A. et al. Early combination antibiotic therapy yields improved survival compared with monotherapy in septic shock: a propensity-matched analysis. Crit. Care Med. 38, 1773–1785 (2010).

Micek, S. T. et al. Empiric combination antibiotic therapy is associated with improved outcome against sepsis due to Gram-negative bacteria: a retrospective analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 1742–1748 (2010).

Sprung, C. L. et al. An evaluation of systemic inflammatory response syndrome signs in the Sepsis Occurrence In Acutely Ill Patients (SOAP) study. Intensive Care Med. 32, 421–427 (2006).

Vincent, J. L. et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA 302, 2323–2329 (2009).

Heenen, S., Jacobs, F. & Vincent, J. L. Antibiotic strategies in severe nosocomial sepsis: why do we not de-escalate more often? Crit. Care Med. 40, 1404–1409 (2012).

Vincent, J. L. & De Backer, D. Circulatory shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 583 (2014).

Dellinger, R. P. et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 39, 165–228 (2013).

Rivers, E. et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 345, 1368–1377 (2001). This seminal clinical trial demonstrates that EGDT bundles could significantly reduce mortality in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. This study played a major supportive part in the use of standardized treatment bundles.

ProCESS Investigators et al. A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early septic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 1683–1693 (2014). This is an important and somewhat controversial study showing that EGDT did not improve 60-day survival in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. These data were inconsistent with results by Rivers et al. (reference 113) found 13 years earlier; the explanation is thought to do with the better management of the control groups receiving standard care.

Weil, M. H. & Shubin, H. The “VIP” approach to the bedside management of shock. JAMA 207, 337–340 (1969).

Reinhart, K. et al. Consensus statement of the ESICM task force on colloid volume therapy in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 38, 368–383 (2012).

Myburgh, J. A. Fluid resuscitation in acute medicine: what is the current situation? J. Intern. Med. 277, 58–68 (2015).

De Backer, D., Aldecoa, C., Njimi, H. & Vincent, J. L. Dopamine versus norepinephrine in the treatment of septic shock: a meta-analysis. Crit. Care Med. 40, 725–730 (2012).

De Backer, D. et al. Comparison of dopamine and norepinephrine in the treatment of shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 779–789 (2010).

Jones, A. E. et al. Lactate clearance versus central venous oxygen saturation as goals of early sepsis therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 303, 739–746 (2010).

He, X. et al. A selective V1A receptor agonist, selepressin, is superior to arginine vasopressin and to norepinephrine in ovine septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 44, 23–31 (2016).

Marshall, J. C. Why have clinical trials in sepsis failed? Trends Mol. Med. 20, 195–203 (2014).

Alejandria, M. M., Lansang, M. A., Dans, L. F. & Mantaring, J. B. 3rd. Intravenous immunoglobulin for treating sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9, CD001090 (2013).

Fisher, C. J. Jr et al. Treatment of septic shock with the tumor necrosis factor receptor:Fc fusion protein. The Soluble TNF Receptor Sepsis Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 334, 1697–1702 (1996).

Qiu, P. et al. The evolving experience with therapeutic TNF inhibition in sepsis: considering the potential influence of risk of death. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 20, 1555–1564 (2011).

Cross, G. et al. The epidemiology of sepsis during rapid response team reviews in a teaching hospital. Anaesth. Intensive Care 43, 193–198 (2015).

Lehman, K. D. & Thiessen, K. Sepsis guidelines: clinical practice implications. Nurse Pract. 40, 1–6 (2015).

Zubrow, M. T. et al. Improving care of the sepsis patient. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 34, 187–191 (2008).

Dowdy, D. W. et al. Quality of life in adult survivors of critical illness: a systematic review of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 31, 611–620 (2005).

Prescott, H. C., Langa, K. M., Liu, V., Escobar, G. J. & Iwashyna, T. J. Increased 1-year healthcare use in survivors of severe sepsis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 190, 62–69 (2014). Using an administrative database, the authors demonstrate that individuals in hospital who survived severe sepsis spent considerable time rehospitalized and had high out-of-hospital mortality rates in the year following sepsis survival.

Nelson, J. E. et al. The symptom burden of chronic critical illness. Crit. Care Med. 32, 1527–1534 (2004).

Baldwin, M. R. Measuring and predicting long-term outcomes in older survivors of critical illness. Minerva Anestesiol. 81, 650–661 (2015).

Kaarlola, A., Tallgren, M. & Pettila, V. Long-term survival, quality of life, and quality-adjusted life-years among critically ill elderly patients. Crit. Care Med. 34, 2120–2126 (2006).

Mehlhorn, J. et al. Rehabilitation interventions for postintensive care syndrome: a systematic review. Crit. Care Med. 42, 1263–1271 (2014).

Battle, C. E., Davies, G. & Evans, P. A. Long term health-related quality of life in survivors of sepsis in South West Wales: an epidemiological study. PLoS ONE 9, e116304 (2014).

Semmler, A. et al. Persistent cognitive impairment, hippocampal atrophy and EEG changes in sepsis survivors. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 84, 62–69 (2013).

Parker, A. M. et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit. Care Med. 43, 1121–1129 (2015).

Hofhuis, J. G. et al. The impact of critical illness on perceived health-related quality of life during ICU treatment, hospital stay, and after hospital discharge: a long-term follow-up study. Chest 133, 377–385 (2008).

Poulsen, J. B., Moller, K., Kehlet, H. & Perner, A. Long-term physical outcome in patients with septic shock. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 53, 724–730 (2009).

Dellinger, R. P. et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 32, 858–873 (2004).

Bernard, G. R. et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 699–709 (2001).

Lai, P. S. & Thompson, B. T. Why activated protein C was not successful in severe sepsis and septic shock: are we still tilting at windmills? Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 15, 407–412 (2013).

Blum, C. A. et al. Adjunct prednisone therapy for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 385, 1511–1518 (2015).

Torres, A. et al. Effect of corticosteroids on treatment failure among hospitalized patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia and high inflammatory response: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 313, 677–686 (2015).

Kang, J. H. et al. An extracorporeal blood-cleansing device for sepsis therapy. Nat. Med. 20, 1211–1216 (2014).

Hutchins, N. A., Unsinger, J., Hotchkiss, R. S. & Ayala, A. The new normal: immunomodulatory agents against sepsis immune suppression. Trends Mol. Med. 20, 224–233 (2014). This paper surmises that, after many unsuccessful attempts to decrease the inflammatory response in randomized controlled trials, the possible place of immunostimulating strategies in sepsis is a reasonable option.

Meisel, C. et al. Granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor to reverse sepsis-associated immunosuppression: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 180, 640–648 (2009).

US National Library of Medicine. Does GM-CSF restore neutrophil phagocytosis in critical illness? (GMCSF). ClinicalTrials.govhttp://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01653665 (2012).

US National Library of Medicine. The effects of interferon-gamma on sepsis-induced immunoparalysis. ClinicalTrials.govhttp://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01649921 (2012).

US National Library of Medicine. Safety, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of BMS-936559 in severe sepsis. ClinicalTrials.govhttps://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02576457 (2015).

Wu, J. et al. The efficacy of thymosin alpha 1 for severe sepsis (ETASS): a multicenter, single-blind, randomized and controlled trial. Crit. Care 17, R8 (2013).

Hotchkiss, R. S. & Moldawer, L. L. Parallels between cancer and infectious disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 380–383 (2014). Sepsis and cancer have many features in common, including that both are heterogeneous conditions; the host response has an essential role in the evolution of the diseases.

Mackall, C. L., Fry, T. J. & Gress, R. E. Harnessing the biology of IL-7 for therapeutic application. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 330–342 (2011).

US National Library of Medicine. CYT107 after vaccine treatment (Provenge) in patients with metastatic hormone-resistant prostate cancer. ClinicalTrials.govhttps://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01881867 (2013).

Levy, Y. et al. Effects of recombinant human interleukin 7 on T-cell recovery and thymic output in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy: results of a phase I/IIa randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 55, 291–300 (2012).

Venet, F. et al. IL-7 restores lymphocyte functions in septic patients. J. Immunol. 189, 5073–5081 (2012).

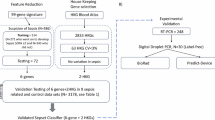

Sweeney, T. E., Shidham, A., Wong, H. R. & Khatri, P. A comprehensive time-course-based multicohort analysis of sepsis and sterile inflammation reveals a robust diagnostic gene set. Sci. Transl Med. 7, 287ra71 (2015). Investigating a large number of publically available gene expression sets, the authors identify a pattern of gene expression that can be used to diagnose sepsis in a clear demonstration that ‘-omics’ is being used to diagnose and prognose sepsis.

Maslove, D. M. & Wong, H. R. Gene expression profiling in sepsis: timing, tissue, and translational considerations. Trends Mol. Med. 20, 204–213 (2014).

Sutherland, A. et al. Development and validation of a novel molecular biomarker diagnostic test for the early detection of sepsis. Crit. Care 15, R149 (2011).

Davenport, E. E. et al. Genomic landscape of the individual host response and outcomes in sepsis: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med. 4, 259–271 (2016).

Chung, L. P. & Waterer, G. W. Genetic predisposition to respiratory infection and sepsis. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 48, 250–268 (2011).

Bone, R. C. et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest 101, 1644–1655 (1992).

Teasdale, G. & Jennett, B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet 2, 81–84 (1974).

Williams, M. D. et al. Hospitalized cancer patients with severe sepsis: analysis of incidence, mortality, and associated costs of care. Crit. Care 8, R291–R298 (2004).

Bone, R. C. Sir Isaac Newton, sepsis, SIRS, and CARS. Crit. Care Med. 24, 1125–1128 (1996).

US National Library of Medicine. Trebananib in treating patients with persistent or recurrent endometrial cancer. ClinicalTrials.govhttps://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01210222 (2010).

US National Library of Medicine. ACT-128800 in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. ClinicalTrials.govhttps://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01006265 (2009).

US National Library of Medicine. ACT-128800 in psoriasis. ClinicalTrials.govhttps://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00852670 (2009).

US National Library of Medicine. Efficacy of FX06 in the prevention of myocardial reperfusion injury. ClinicalTrials.govhttps://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00326976 (2006).

US National Library of Medicine. Safety study of PZ-128 in subjects with multiple coronary artery disease risk factors. ClinicalTrials.govhttps://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01806077 (2013).

Thomas, G. et al. Statin therapy in critically-ill patients with severe sepsis: a review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Minerva Anestesiol. 81, 921–930 (2015).

US National Library of Medicine. Selepressin evaluation programme for sepsis-induced shock — adaptive clinical trial (SEPSIS-ACT). ClinicalTrials.govhttps://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02508649 (2015).

Wang, C. et al. Low-dose hydrocortisone therapy attenuates septic shock in adult patients but does not reduce 28-day mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth. Analg. 118, 346–357 (2014).

Annane, D. et al. Corticosteroids in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock in adults: a systematic review. JAMA 301, 2362–2375 (2009).

Russell, J. A. et al. Vasopressin versus norepinephrine infusion in patients with septic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 877–887 (2008).

Angus, D. C. et al. E5 murine monoclonal antiendotoxin antibody in Gram-negative sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. E5 Study Investigators. JAMA 283, 1723–1730 (2000).

McCloskey, R. V., Straube, R. C., Sanders, C., Smith, S. M. & Smith, C. R. Treatment of septic shock with human monoclonal antibody HA-1A. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CHESS Trial Study Group. Ann. Intern. Med. 121, 1–5 (1994).

Dellinger, R. P. et al. Efficacy and safety of a phospholipid emulsion (GR270773) in Gram-negative severe sepsis: results of a phase II multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-finding clinical trial. Crit. Care Med. 37, 2929–2938 (2009).

Levin, M. et al. Recombinant bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (rBPI21) as adjunctive treatment for children with severe meningococcal sepsis: a randomised trial. rBPI21 Meningococcal Sepsis Study Group. Lancet 356, 961–967 (2000).

Opal, S. M. et al. Effect of eritoran, an antagonist of MD2-TLR4, on mortality in patients with severe sepsis: the ACCESS randomized trial. JAMA 309, 1154–1162 (2013).

Rice, T. W. et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of TAK-242 for the treatment of severe sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 38, 1685–1694 (2010).

Axtelle, T. & Pribble, J. An overview of clinical studies in healthy subjects and patients with severe sepsis with IC14, a CD14-specific chimeric monoclonal antibody. J. Endotoxin Res. 9, 385–389 (2003).

Abraham, E. et al. Double-blind randomised controlled trial of monoclonal antibody to human tumour necrosis factor in treatment of septic shock. NORASEPT II Study Group. Lancet 351, 929–933 (1998).

Cohen, J. & Carlet, J. INTERSEPT: an international, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of monoclonal antibody to human tumor necrosis factor-α in patients with sepsis. International Sepsis Trial Study Group. Crit. Care Med. 24, 1431–1440 (1996).

Abraham, E. et al. Lenercept (p55 tumor necrosis factor receptor fusion protein) in severe sepsis and early septic shock: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III trial with 1,342 patients. Crit. Care Med. 29, 503–510 (2001).

Opal, S. M. et al. Confirmatory interleukin-1 receptor antagonist trial in severe sepsis: a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. The Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist Sepsis Investigator Group. Crit. Care Med. 25, 1115–1124 (1997).

Poeze, M., Froon, A. H., Ramsay, G., Buurman, W. A. & Greve, J. W. Decreased organ failure in patients with severe SIRS and septic shock treated with the platelet-activating factor antagonist TCV-309: a prospective, multicenter, double-blind, randomized phase II trial. TCV-309 Septic Shock Study Group. Shock 14, 421–428 (2000).

Suputtamongkol, Y. et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of an infusion of lexipafant (platelet-activating factor receptor antagonist) in patients with severe sepsis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 693–696 (2000).

Bernard, G. R. et al. The effects of ibuprofen on the physiology and survival of patients with sepsis. The Ibuprofen Sepsis Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 336, 912–918 (1997).

Zeiher, B. G. et al. LY315920NA/S-5920, a selective inhibitor of group IIA secretory phospholipase A2, fails to improve clinical outcome for patients with severe sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 33, 1741–1748 (2005).

Bakker, J. et al. Administration of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor NG-methyl-l-arginine hydrochloride (546C88) by intravenous infusion for up to 72 hours can promote the resolution of shock in patients with severe sepsis: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study (study no. 144–002). Crit. Care Med. 32, 1–12 (2004).

Preiser, J. C. et al. Methylene blue administration in septic shock: a clinical trial. Crit. Care Med. 23, 259–264 (1995).

Annane, D. et al. Recombinant human activated protein C for adults with septic shock: a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 187, 1091–1097 (2013).

Abraham, E. et al. Efficacy and safety of tifacogin (recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor) in severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290, 238–247 (2003).

Warren, B. L. et al. Caring for the critically ill patient. High-dose antithrombin III in severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 286, 1869–1878 (2001).

Morris, P. E. et al. A phase I study evaluating the pharmacokinetics, safety and tolerability of an antibody-based tissue factor antagonist in subjects with acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome. BMC Pulm. Med. 12, 5 (2012).

Zarychanski, R. et al. The efficacy and safety of heparin in patients with sepsis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Crit. Care Med. 43, 511–518 (2015).

Vincent, J. L. et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin, ART-123, in patients with sepsis and suspected disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit. Care Med. 41, 2069–2079 (2013).

Kong, Z., Wang, F., Ji, S., Deng, X. & Xia, Z. Selenium supplementation for sepsis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 31, 1170–1175 (2013).

Fein, A. M. et al. Treatment of severe systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis with a novel bradykinin antagonist, deltibant (CP-0127). Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CP-0127 SIRS and Sepsis Study Group. JAMA 277, 482–487 (1997).

Spapen, H. D., Diltoer, M. W., Nguyen, D. N., Hendrickx, I. & Huyghens, L. P. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on microalbuminuria and organ failure in acute severe sepsis: results of a pilot study. Chest 127, 1413–1419 (2005).

Szakmany, T., Hauser, B. & Radermacher, P. N-acetylcysteine for sepsis and systemic inflammatory response in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9, CD006616 (2012).

Reinhart, K. et al. Open randomized phase II trial of an extracorporeal endotoxin adsorber in suspected Gram-negative sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 32, 1662–1668 (2004).

Flohe, S. et al. Effect of granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor on the immune response of circulating monocytes after severe trauma. Crit. Care Med. 31, 2462–2469 (2003).

Leentjens, J. et al. Reversal of immunoparalysis in humans in vivo: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized pilot study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 186, 838–845 (2012).

Woods, D. R. & Mason, D. D. Six areas lead national early immunization drive. Public Health Rep. 107, 252–256 (1992).

Root, R. K. et al. Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the use of filgrastim in patients hospitalized with pneumonia and severe sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 31, 367–373 (2003).

Nelson, S. et al. A randomized controlled trial of filgrastim as an adjunct to antibiotics for treatment of hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. CAP Study Group. J. Infect. Dis. 178, 1075–1080 (1998).

Dries, D. J. Interferon gamma in trauma-related infections. Intensive Care Med. 22, S462–S467 (1996).

Dries, D. J. et al. Effect of interferon gamma on infection-related death in patients with severe injuries. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch. Surg. 129, 1031–1041; discussion 1042 (1994).

Kasten, K. R. et al. Interleukin-7 (IL-7) treatment accelerates neutrophil recruitment through γδ T-cell IL-17 production in a murine model of sepsis. Infect. Immun. 78, 4714–4722 (2010).

Unsinger, J. et al. Interleukin-7 ameliorates immune dysfunction and improves survival in a 2-hit model of fungal sepsis. J. Infect. Dis. 206, 606–616 (2012).

Inoue, S. et al. IL-15 prevents apoptosis, reverses innate and adaptive immune dysfunction, and improves survival in sepsis. J. Immunol. 184, 1401–1409 (2010).

Pelletier, M., Ratthe, C. & Girard, D. Mechanisms involved in interleukin-15-induced suppression of human neutrophil apoptosis: role of the anti-apoptotic Mcl-1 protein and several kinases including Janus kinase-2, 38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinases-1/2. FEBS Lett. 532, 164–170 (2002).

Saikh, K. U., Kissner, T. L., Nystrom, S., Ruthel, G. & Ulrich, R. G. Interleukin-15 increases vaccine efficacy through a mechanism linked to dendritic cell maturation and enhanced antibody titers. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 15, 131–137 (2008).

Chen, H., He, M. Y. & Li, Y. M. Treatment of patients with severe sepsis using ulinastatin and thymosin α1: a prospective, randomized, controlled pilot study. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 122, 883–888 (2009).

Chang, K. C. et al. Blockade of the negative co-stimulatory molecules PD-1 and CTLA-4 improves survival in primary and secondary fungal sepsis. Crit. Care 17, R85 (2013).

Huang, X. et al. PD-1 expression by macrophages plays a pathologic role in altering microbial clearance and the innate inflammatory response to sepsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 6303–6308 (2009).

West, E. E. et al. PD-L1 blockade synergizes with IL-2 therapy in reinvigorating exhausted T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 2604–2615 (2013).

Inoue, S. et al. Dose-dependent effect of anti-CTLA-4 on survival in sepsis. Shock 36, 38–44 (2011).

Yang, X. et al. T cell Ig mucin-3 promotes homeostasis of sepsis by negatively regulating the TLR response. J. Immunol. 190, 2068–2079 (2013).

Zhao, Z. et al. Blockade of the T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain protein 3 pathway exacerbates sepsis-induced immune deviation and immunosuppression. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 178, 279–291 (2014).

Workman, C. J. et al. LAG-3 regulates plasmacytoid dendritic cell homeostasis. J. Immunol. 182, 1885–1891 (2009).

Durham, N. M. et al. Lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG-3) modulates the ability of CD4 T-cells to be suppressed in vivo. PLoS ONE 9, e109080 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This Primer does not promulgate the clinical use of a drug that is not approved by the US FDA or the off-label use of any FDA-approved drug.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authorship is ordered alphabetically. Introduction (L.L.M. and J.-L.V.); Epidemiology (J.-L.V., K.R. and S.M.O.); Mechanisms/pathophysiology (L.L.M., R.S.H., I.R.T. and K.R.); Diagnosis, screening and prevention (L.L.M., J.-L.V. and S.M.O.); Management (J.-L.V., S.M.O., R.S.H. and I.R.T.); Quality of life (L.L.M.); Outlook (all authors); Overview of the Primer (L.L.M.).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

R.S.H. has received no direct financial support, nor does he or his family hold patents or equity interest in any biotech or pharmaceutical company. He has received laboratory research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline and Medimmune. He has served as a paid consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Medimmune and Merck. R.S.H. and Washington University in St Louis, Missouri, USA, have also received grant support from the US NIH, US Public Health Service for research investigations of sepsis. L.L.M. and the University of Florida College of Medicine, USA, have received financial support from the US National Institute of General Medical Sciences, US Public Health Service. No other financial support, patents or equity interest to him or his family are disclosed. S.M.O. has received no direct financial support, nor does he or his family hold patents or equity interest in any biotech or pharmaceutical company. S.M.O. and Brown University, Rhode Island, USA, have received preclinical grants in the past from the NIH, US Public Health Service, Atoxbio, GlaxoSmithKline and Arsanis, and have received financial support for assistance with clinical trial coordination from Asahi Kasei, Ferring, Cardeas and Biocartis. S.M.O. serves as a member of the Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) for Paratek (for Omadcycline), Acheogen (for Placomicin) and Bristol-Myers Squibb (anti-PDL1 monoclonal antibody). He also serves on the DSMB for two NIH-funded studies: one examining procalcitonin-guided antibiotic administration and the other investigating early intervention for community-acquired sepsis. S.M.O. serves as a paid consultant for BioAegis, Arsanis, Aridis, Batelle and Cyon on various biodefense and monoclonal antibody projects. He also receives royalty payments from Elsevier publishers for the textbook entitled, Infectious Diseases 4th edition. K.R. holds an equity interest in InflaRx and is a paid consultant for Adrenomed. J.-L.V. and I.R.T. declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hotchkiss, R., Moldawer, L., Opal, S. et al. Sepsis and septic shock. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2, 16045 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.45

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.45

This article is cited by

-

Update on vitamin D role in severe infections and sepsis

Journal of Anesthesia, Analgesia and Critical Care (2024)

-

Interorgan communication networks in the kidney–lung axis

Nature Reviews Nephrology (2024)

-

Severe neurological impairment and immune function: altered neutrophils, monocytes, T lymphocytes, and inflammasome activation

Pediatric Research (2024)

-

Investigating the efficacy of dapsone in treating sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture surgery in male mice

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology (2024)

-

Serum Lactate Is an Indicator for Short-Term and Long-Term Mortality in Patients with Acute Pancreatitis

Digestive Diseases and Sciences (2024)