Abstract

Background

Research suggests a putative role of the glucocorticoid stress hormone cortisol in the accumulation of adiposity. However, obesity and weight fluctuations may also wear and tear physiological systems promoting adaptation, affecting cortisol secretion. This possibility remains scarcely investigated in longitudinal research. This study tests whether trajectories of body mass index (BMI) across the first 15 years of life are associated with hair cortisol concentration (HCC) measured two years later and whether variability in BMI and timing matter.

Methods

BMI (kg/m2) was prospectively measured at twelve occasions between age 5 months and 15 years. Hair was sampled at age 17 in 565 participants. Sex, family socioeconomic status, and BMI measured concurrently to HCC were considered as control variables.

Results

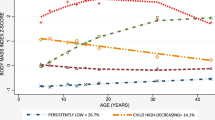

Latent class analyses identified three BMI trajectories: “low-stable” (59.2%, n = 946), “moderate” (32.6%, n = 507), and “high-rising” (8.2%, n = 128). BMI variability was computed by dividing the standard deviation of an individual’s BMI measurements by the mean of these measurements. Findings revealed linear effects, such that higher HCC was noted for participants with moderate BMI trajectories in comparison to low-stable youth (β = 0.10, p = 0.03, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [0.02–0.40]); however, this association was not detected in the high-rising BMI youth (β = −0.02, p = 0.71, 95% CI = [−0.47–0.32]). Higher BMI variability across development predicted higher cortisol (β = 0.17, p = 0.003, 95% CI = [0.10–4.91]), additively to the contribution of BMI trajectories. BMI variability in childhood was responsible for that finding, possibly suggesting a timing effect.

Conclusions

This study strengthens empirical support for BMI-HCC association and suggests that more attention should be devoted to BMI fluctuations in addition to persistent trajectories of BMI.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study were obtained from a third party, the Institut de la statistique du Québec, and are not publicly available due to the privacy legislation in the province of Québec, Canada. Requests to access these data can be directed to the Institut de la statistique du Québec’s Research Data Access Services - Home (www.quebec.ca). For more information, contact Marc-Antoine Côté-Marcil (marc-antoine.cote-marcil@stat.gouv.qc.ca).

References

Daniels SR, Arnett DK, Eckel RH, Gidding SS, Hayman LL, Kumanyika S, et al. AHA scientific statement: overweight in children and adolescents: pathophysiology, consequences, prevention, and treatment. Circulation. 2005;111:1999–2012.

Rebuffé-Scrive M, Walsh UA, McEwen B, Rodin J. Effect of chronic stress and exogenous glucocorticoids on regional fat distribution and metabolism. Physiol Behav. 1992;52:583–90.

van der Valk ES, Savas M, van Rossum E. Stress and obesity: are there more susceptible individuals? Curr Obes Rep. 2018;7:193–203.

Travison TG, O’Donnell AB, Araujo AB, Matsumoto AM, McKinlay JB. Cortisol levels and measures of body composition in middle-aged and older men. Clin Endocrinol. 2007;67:71–7.

Van Rossum EFC. Obesity and cortisol: new perspectives on an old theme. Obes Cortisol Obes 2017;25:500–1.

Rao DP, Kropac E, Do MT, Roberts KC, Jayaraman GC. Childhood overweight and obesity trends in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2016;36:194–8.

Skinner AC, Ravanbakht SN, Skelton JA, Perrin EM, Armstrong SC. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity in US children, 1999–2016. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20173459.

Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, Woolacott N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17:95–107.

Pulgarón ER. Childhood obesity: a review of increased risk for physical and psychological comorbidities. Clin Ther. 2013;35:A18–32.

Cunningham JJ, Calles-Escandon J, Garrido F, Carr DB, Bode HH. Hypercorticosteronuria and diminished pituitary responsiveness to corticotropin-releasing factor in Obese Zucker Rats*. Endocrinology. 1986;118:98–101.

Naeser P. Effects of adrenalectomy on the obese-hyperglycemic syndrome in mice (gene symbolob). Diabetologia. 1973;9:376–9.

Shibli-Rahhal A, Van Beek M, Schlechte JA. Cushing’s syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:260–5.

Bose M, Oliván B, Laferrère B. Stress and obesity: the role of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in metabolic disease. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2009;16:340–6.

Klimes–Dougan B, Hastings PD, Granger DA, Usher BA, Zahn–Waxler C. Adrenocortical activity in at-risk and normally developing adolescents: Individual differences in salivary cortisol basal levels, diurnal variation, and responses to social challenges. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13:695–719.

El-Farhan N, Rees DA, Evans C. Measuring cortisol in serum, urine and saliva – are our assays good enough? Ann Clin Biochem. 2017;54:308–22.

Stalder T, Steudte-Schmiedgen S, Alexander N, Klucken T, Vater A, Wichmann S, et al. Stress-related and basic determinants of hair cortisol in humans: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;77:261–74.

Veldhorst MAB, Noppe G, Jongejan MHTM, Kok CBM, Mekic S, Koper JW, et al. Increased scalp hair cortisol concentrations in obese children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:285–90.

Noppe G, van den Akker ELT, de Rijke YB, Koper JW, Jaddoe VW, van Rossum EFC. Long-term glucocorticoid concentrations as a risk factor for childhood obesity and adverse body-fat distribution. Int J Obes. 2016;40:1503–9.

Larsen SC, Fahrenkrug J, Olsen NJ, Heitmann BL. Association between hair cortisol concentration and adiposity measures among children and parents from the “Healthy Start” Study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0163639.

Olstad DL, Ball K, Wright C, Abbott G, Brown E, Turner AI. Hair cortisol levels, perceived stress and body mass index in women and children living in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods: the READI study. Stress. 2016;19:158–67.

Del Giudice M, Ellis BJ, Shirtcliff EA. The adaptive calibration model of stress responsivity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(Jun):1562–92.

Trickett PK, Noll JG, Susman EJ, Shenk CE, Putnam FW. Attenuation of cortisol across development for victims of sexual abuse. Dev Psychopathol. 2010;22:165–75.

Ruttle PL, Javaras KN, Klein MH, Armstrong JM, Burk LR, Essex MJ. Concurrent and longitudinal associations between diurnal cortisol and body mass index across adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:731–7.

Orri M, Boivin M, Chen C, Ahun MN, Geoffroy MC, Ouellet-Morin I, et al. Cohort profile: Quebec longitudinal study of child development (QLSCD). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2021;56:883–94.

Van Hulst A, Wills-Ibarra N, Nikiéma B, Kakinami L, Pratt KJ, Ball GDC. Associations between family functioning during early to mid-childhood and weight status in childhood and adolescence: findings from a Quebec birth cohort. Int J Obes. 2022;46:986–91.

Oskis A, Loveday C, Hucklebridge F, Thorn L, Clow A. Diurnal patterns of salivary cortisol across the adolescent period in healthy females. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:307–16.

Netherton C, Goodyer I, Tamplin A, Herbert J. Salivary cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone in relation to puberty and gender. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:125–40.

Cole TJ, Faith MS, Pietrobelli A, Heo M. What is the best measure of adiposity change in growing children: BMI, BMI %, BMI z-score or BMI centile? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:419–25.

Pryor LE, Brendgen M, Tremblay RE, Pingault JB, Liu X, Dubois L, et al. Early risk factors of overweight developmental trajectories during middle childhood. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0131231.

Ouellet-Morin I, Laurin M, Robitaille MP, Brendgen M, Lupien SJ, Boivin M, et al. Validation of an adapted procedure to collect hair for cortisol determination in adolescents. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;70:58–62.

Kirschbaum C, Tietze A, Skoluda N, Dettenborn L. Hair as a retrospective calendar of cortisol production—Increased cortisol incorporation into hair in the third trimester of pregnancy. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:32–7.

Ouellet-Morin I, Cantave C, Paquin S, Geoffroy MC, Brendgen M, Vitaro F, et al. Associations between developmental trajectories of peer victimization, hair cortisol, and depressive symptoms: a longitudinal study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;62(Jan):19–27.

Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus statistical modeling software: Release 7.0. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2012.

Kumari M, Chandola T, Brunner E, Kivimaki M. A nonlinear relationship of generalized and central obesity with diurnal cortisol secretion in the Whitehall ii study. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2010;95:4415–23.

Miller GE, Chen E, Zhou ES. If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:25.

Ruttle PL, Shirtcliff EA, Serbin LA, Ben-Dat Fisher D, Stack DM, Schwartzman AE. Disentangling psychobiological mechanisms underlying internalizing and externalizing behaviors in youth: Longitudinal and concurrent associations with cortisol. Hormones Behav. 2011;59:123–32.

Fries E, Hesse J, Hellhammer J, Hellhammer DH. A new view on hypocortisolism. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:1010–6.

McEwen BS, Wingfield JC. The concept of allostasis in biology and biomedicine. Hormones Behav. 2003;43:2–15.

McEwen BS, Stellar E. Stress and the individual: mechanisms leading to disease. Arch Internal Med. 1993;153:2093–101.

Shonkoff JP. Building a new biodevelopmental framework to guide the future of early childhood policy. Child Dev. 2010;81:357–67.

Huybrechts I, Himes JH, Ottevaere C, De Vriendt T, De Keyzer W, Cox B, et al. Validity of parent-reported weight and height of preschool children measured at home or estimated without home measurement: a validation study. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:63.

Sherry B, Jefferds ME, Grummer-Strawn LM. Accuracy of adolescent self-report of height and weight in assessing overweight status: a literature review. Arch Pediatr Adolescent Med. 2007;161:1154–61.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants who have given their time to take part in this study. Christina Y. Cantave holds a postdoctoral fellowship grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Isabelle Ouellet-Morin is the Canada Research Chair in the Developmental Origins of Vulnerability and Resilience. Michel Boivin is a Canada Research Chair in Child Development. Sonia J Lupien is a Canada Research Chair in Human Stress and is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research’s Foundation grant. Richard E. Tremblay was funded by the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research and the Canada Research Chair in Child Development. Marie-Claude Geoffroy holds a CRC (TIER-2) in Youth Suicide Prevention. The authors would like to acknowledge Elizabeth Shirtcliff for reviewing the manuscript. These results were presented at the ISPNE 2020 conference.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CYC: Responsible for data analyses, interpretation and the writing of the paper. PLR: Responsible for study design, data analyses and interpretation, and wrote a first draft of the paper. SMC: Data collection and provided feedback on the report. SJL: Data collection and provided feedback on the report. MCG: Provided feedback on the report. MB: Provided feedback on the report. RT: Data collection and provided feedback on the report. MB: Data collection and provided feedback on the report. IOM: Responsible for study design, data collection, data analyses, writing the paper, interpretation, and provided feedback on the report.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The present study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Quebec Funds for Research (FQRS, FQRSC), and the Government of Quebec through the Institut de la Statistique du Québec who collected the data. The funding sources had no involvement in the interpretation of data, writing of the report, and the decision to submit the article for publication. All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cantave, C.Y., Ruttle, P.L., Coté, S.M. et al. Body mass index across development and adolescent hair cortisol: the role of persistence, variability, and timing of exposure. Int J Obes 49, 125–132 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01640-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01640-1