Abstract

Background

Past work demonstrating an association between indoor air quality and cognitive performance brought attention to the benefits of increasing outdoor air ventilation rates beyond code minimums. These code minimums were scrutinized during the COVID-19 pandemic for insufficient ventilation and filtration specifications. As higher outdoor air ventilation was recommended in response, questions arose about potential benefits of enhanced ventilation beyond infection risk reduction.

Objective

This was investigated by examining associations between indoor carbon dioxide concentrations, reflective of ventilation and building occupancy, and cognitive test scores among graduate students attending lectures in university classrooms with infection risk management strategies, namely increased ventilation.

Methods

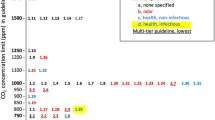

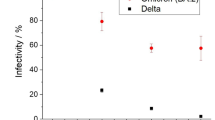

Post-class cognitive performance tests (Stroop, assessing inhibitory control and selective attention; Arithmetic, assessing cognitive speed and working memory) were administered through a smartphone application to participating students (54 included in analysis) over the 2022–2023 academic year in classrooms equipped with continuous indoor environmental quality monitors that provided real-time measurements of classroom carbon dioxide concentrations. Temporally and spatially paired exposure and outcome data was used to construct mixed effects statistical models that examined different carbon dioxide exposure metrics and cognitive test scores.

Results

Model estimates show directionally consistent evidence that higher central and peak classroom carbon dioxide concentrations, indicative of ventilation and occupancy, are associated with lower cognitive test scores over the measured range included in analysis ( ~ 440–1630 ppm). The effect estimates are strongest for 95th percentile class carbon dioxide concentrations, representing peak class carbon dioxide exposures.

Impact statement

-

As the COVID-19 pandemic eased, questions emerged on the benefits of increased outdoor air ventilation beyond infection reduction. This work assesses associations between carbon dioxide concentrations, indicative of ventilation and occupancy, and cognitive test scores among students in university classrooms with increased outdoor air ventilation. Although not causal, models show statistically significant evidence of associations between lower carbon dioxide concentrations and higher cognitive test scores over the low range of carbon dioxide exposures in these classrooms. While the underlying mechanisms remain unknown, higher outdoor air ventilation appears to provide additional benefits by reducing indoor air exposure and supporting student performance.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 6 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $43.17 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Requests for the data supporting these findings should be sent to the corresponding author.

References

Du B, Tandoc MC, Mack ML, Siegel JA. Indoor CO 2 concentrations and cognitive function: a critical review. Indoor Air. 2020;30:1067–82.

Cedeño Laurent JG, MacNaughton P, Jones E, Young AS, Bliss M, Flanigan S, et al. Associations between acute exposures to PM 2.5 and carbon dioxide indoors and cognitive function in office workers: a multicountry longitudinal prospective observational study. Environ Res Lett. 2021;16:094047.

Wargocki P, Wyon DP, Sundell J, Clausen G, Fanger PO. The effects of outdoor air supply rate in an office on perceived air quality, sick building syndrome (SBS) symptoms and productivity. Indoor Air. 2000;10:222–36.

Dedesko S, Pendleton J, Petrov J, Coull BA, Spengler JD, Allen JG Associations between indoor environmental conditions and divergent creative thinking scores in the cogfx global buildings study. Build Environ. 2025;270:112531.

Allen JG, MacNaughton P, Satish U, Santanam S, Vallarino J, Spengler JD. Associations of cognitive function scores with carbon dioxide, ventilation, and volatile organic compound exposures in office workers: a controlled exposure study of green and conventional office environments. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:805–12.

Maddalena R, Mendell MJ, Eliseeva K, Chan WR, Sullivan DP, Russell M, et al. Effects of ventilation rate per person and per floor area on perceived air quality, sick building syndrome symptoms, and decision-making. Indoor Air. 2015;25:362–70.

Tham KW. Effects of temperature and outdoor air supply rate on the performance of call center operators in the tropics. Indoor Air. 2004;14:119–25.

Wargocki P, Wyon DP, Fanger PO. The performance and subjective responses of call-center operators with new and used supply air filters at two outdoor air supply rates. Indoor Air. 2004;14:7–16.

Young A, Parikh S, Dedesko S, Bliss M, Xu J, Zanobetti A, et al. Home indoor air quality and cognitive function over one year for people working remotely during COVID-19. Build Environ. 2024;257:111551.

Riham Jaber A, Dejan M, Marcella U. The effect of indoor temperature and CO2 levels on cognitive performance of adult females in a university building in Saudi Arabia. Energy Procedia. 2017;122:451–6.

Joanne S. The link between buildings and cognitive performance.

Haverinen-Shaughnessy U, Shaughnessy RJ. Effects of classroom ventilation rate and temperature on students’ test scores. Shaman J, editor. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0136165.

Wargocki P, Wyon DP. The effects of moderately raised classroom temperatures and classroom ventilation rate on the performance of schoolwork by children (RP-1257). HVACR Res. 2007;13:193–220.

Wargocki P, Wyon DP. The effects of outdoor air supply rate and supply air filter condition in classrooms on the performance of schoolwork by children (RP-1257). HVAC&R Res. 2007;13.

Jareemit D, Julpanwattana P, Choruengwiwat J. Impact of outdoor air exchange rates on sleep quality and the next-day performance with application of energy recovery ventilator. JARS. 2017;14:21–32.

Strøm-Tejsen P, Zukowska D, Wargocki P, Wyon DP. The effects of bedroom air quality on sleep and next-day performance. Indoor Air. 2016;26:679–86.

Künn S, Palacios J, Pestel N. Indoor air quality and strategic decision making. Manag Sci. 2023;mnsc.2022.4643.

Gao X, Coull B, Lin X, Vokonas P, Spiro A, Hou L, et al. Short-term air pollution, cognitive performance and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in the veterans affairs normative aging study. Nat Aging. 2021;1:430–7.

Zhang X, Wargocki P, Lian Z. Human responses to carbon dioxide, a follow-up study at recommended exposure limits in non-industrial environments. Build Environ. 2016;100:162–71.

Persily A Quit Blaming ASHRAE Standard 62.1 for 1000 ppm CO2. Seoul, KR: The 16th Conference of the International Society of Indoor Air Quality & Climate (Indoor Air 2020); 2020. https://tsapps.nist.gov/publication/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=929997.

Persily A. Please don’t blame standard 62.1 for 1000 ppm CO2. ASHRAE J. 2021;63:1–2.

Fisk WJ. The ventilation problem in schools: literature review. Indoor Air. 2017;27:1039–51.

Allen JG, Marr LC. Recognizing and controlling airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in indoor environments. Indoor Air. 2020;30:ina.12697.

Melikov AK. COVID-19: Reduction of airborne transmission needs paradigm shift in ventilation. Build Environ. 2020;186:107336.

Morawska L, Tang JW, Bahnfleth W, Bluyssen PM, Boerstra A, Buonanno G, et al. How can airborne transmission of COVID-19 indoors be minimised. Environ Int. 2020;142:105832.

Sachs JD, Abdool Karim S, Aknin L, Allen J, Brosbøl K, Cuevas Barron G, et al. Lancet COVID-19 Commission Statement on the occasion of the 75th session of the UN General Assembly. Lancet. 2020;396:1102–24.

ASHRAE. ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 62.1-2022, Ventilation and Acceptable Indoor Air Quality. 2022.

Allen JG, Ibrahim AM. Indoor air changes and potential implications for SARS-CoV-2 transmission. JAMA. 2021;325:2112.

Morawska L, Allen J, Bahnfleth W, Bluyssen PM, Boerstra A, Buonanno G, et al. A paradigm shift to combat indoor respiratory infection. Science. 2021;372:689–91.

The Lancet COVID-19 Commission, Task Force on Safe Work, Safe School, and Safe Travel. Proposed Non-infectious Air Delivery Rates (NADR) for Reducing Exposure to Airborne Respiratory Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5ef3652ab722df11fcb2ba5d/t/637740d40f35a9699a7fb05f/1668759764821/Lancet+Covid+Commission+TF+Report+Nov+2022.pdf.

ASHRAE. ASHRAE Standard 241, Control of Infectious Aerosols. 2023.

CDC. Improving Ventilation In Buildings [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Jan 23]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/improving-ventilation-in-buildings.html.

CDC. Ventilation in Buildings [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/ventilation.html#print.

Fox J Equivalent Clean Airflow Rates from ASHRAE 241 Control of Infectious Aerosols (Part 2) [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Jan 23]. Available from: https://itsairborne.com/ashrae-241-control-of-infectious-aerosols-part-2-equivalent-clean-airflow-rates-76a511769d4d.

Callen I, Carbonari MV, DeArmond M, Dewey D, Dizon-Ross E, Goldhaber D et al. Summer School As a Learning Loss Recovery Strategy After COVID-19: Evidence from Summer 2022. Cambridge, MA: Center for Education Policy Research, Harvard University; 2023. Report No.: CALDER Working Paper No. 2901-0823.

Levinson M, Geller AC, Allen JG. Health equity, schooling hesitancy, and the social determinants of learning. Lancet Regional Health - Am. 2021;2:100032.

Lumpkin L, Jayaraman S. Schools got $122 billion to reopen last year. Most has not been used. The Washington Post [Internet]. 2022; Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2022/10/24/covid-spending-schools-students-achievement/.

Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection. Massachusetts 2021 Air Quality Report. 37 Shattuck Street Lawrence, Massachusetts 01843: Department of Environmental Protection Bureau of Air and Waste Division of Air and Climate Programs Air Assessment Branch; 2022.

Goletto V, Mialon G, Faivre T, Wang Y, Lesieur I, Petigny N, et al. Formaldehyde and total VOC (TVOC) commercial low-cost monitoring devices: from an evaluation in controlled conditions to a use case application in a real building. Chemosensors. 2020;8:8.

Molhave L, Clausen G, Berglund B, Ceaurriz J, Kettrup A, Lindvall T, et al. Total volatile organic compounds (TVOC) in indoor air quality investigations*. Indoor Air. 1997;7:225–40.

Barner C, Schmid SR, Diekelmann S. Time-of-day effects on prospective memory. Behav Brain Res. 2019;376:112179.

Hasler BP, Dahl RE, Holm SM, Jakubcak JL, Ryan ND, Silk JS, et al. Weekend-weekday advances in sleep timing are associated with altered reward-related brain function in healthy adolescents. Biol Psychol. 2012;91:334–41.

Scarpina F, Tagini S. The stroop color and word test. Front Psychol. 2017;8:557.

Saenen ND, Provost EB, Viaene MK, Vanpoucke C, Lefebvre W, Vrijens K, et al. Recent versus chronic exposure to particulate matter air pollution in association with neurobehavioral performance in a panel study of primary schoolchildren. Environ Int. 2016;95:112–9.

MacLeod CM Stroop effect in language. In: Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics [Internet]. Elsevier; 2006 [cited 2023 Dec 4]. p. 161–5. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B0080448542008713.

Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1992;121:15–23.

McMorris T History of Research into the Acute Exercise–Cognition Interaction. In: Exercise-Cognition Interaction [Internet]. Elsevier; 2016 [cited 2023 Dec 4]. p. 1–28. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780128007785000013.

Cragg L, Richardson S, Hubber PJ, Keeble S, Gilmore C. When is working memory important for arithmetic? The impact of strategy and age. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0188693.

Zhang Y, Tolmie A, Gordon R. The relationship between working memory and arithmetic in primary school children: a meta-analysis. Brain Sci. 2022;13:22.

Cowan N. Working memory underpins cognitive development, learning, and education. Educ Psychol Rev. 2014;26:197–223.

Liesefeld HR, Janczyk M. Combining speed and accuracy to control for speed-accuracy trade-offs(?). Behav Res. 2019;51:40–60.

Mitchell MR, Potenza MN. Stroop, Cocaine Dependence, and Intrinsic Connectivity. In: The Neuroscience of Cocaine [Internet]. Elsevier; 2017 [cited 2023 Dec 4]. p. 331–9. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780128037508000348.

Periáñez JA, Lubrini G, García-Gutiérrez A, Ríos-Lago M. Construct validity of the stroop color-word test: influence of speed of visual search, verbal fluency, working memory, cognitive flexibility, and conflict monitoring. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2021;36:99–111.

Cedeño Laurent JG, Williams A, Oulhote Y, Zanobetti A, Allen JG, Spengler JD. Reduced cognitive function during a heat wave among residents of non-air-conditioned buildings: An observational study of young adults in the summer of 2016. Patz JA, editor. PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002605.

Lan L, Tang J, Wargocki P, Wyon DP, Lian Z. Cognitive performance was reduced by higher air temperature even when thermal comfort was maintained over the 24–28 °C range. Indoor Air [Internet]. 2022;32:e12916 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ina.12916[cited 2022 Nov 13]Available from.

Porras-Salazar JA, Wyon DP, Piderit-Moreno B, Contreras-Espinoza S, Wargocki P. Reducing classroom temperature in a tropical climate improved the thermal comfort and the performance of elementary school pupils. Indoor Air. 2018;28:892–904.

Seppänen O, Fisk WJ, Lei Q Effect of temperature on task performance in office environment. pdf. Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Lab; 2006. Available from: https://eta-publications.lbl.gov/sites/default/files/lbnl-60946.pdf.

Dedesko S, Jones ER, Allen JG Thermal conditions and associations with divergent creative thinking scores in office environments. In: Proceedings, Indoor Air 2022. Kuopio, Finland. Kuopio, Finland: ISIAQ; 2022.

Goldberg TE, Harvey PD, Wesnes KA, Snyder PJ, Schneider LS. Practice effects due to serial cognitive assessment: implications for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease randomized controlled trials. Alzheimer’s Dement: Diagnosis, Assess Dis Monit. 2015;1:103–11.

ASHRAE. Standard 55-2023—Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy (ANSI Approved). 2023.

Arens E, Heinzerling D, Liu S, Paliaga G, Pande A, Zhai Y, et al. Advances to ASHRAE Standard 55 to encourage more effective building practice. 2020;19.

Pistochini T, Ellis M, Meyers F, Frasier A, Cappa C, Bennett D. Method of test for CO2-based demand control ventilation systems: Benchmarking the state-of-the-art and the undervalued potential of proportional-integral control. Energy Build. 2023;301:113717.

Thom SR, Bhopale VM, Hu J, Yang M. Inflammatory responses to acute elevations of carbon dioxide in mice. J Appl Physiol. 2017;123:297–302.

Thom SR, Bhopale VM, Hu J, Yang M. Increased carbon dioxide levels stimulate neutrophils to produce microparticles and activate the nucleotide-binding domain-like receptor 3 inflammasome. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;106:406–16.

Rodeheffer CD, Chabal S, Clarke JM, Fothergill DM. Acute exposure to low-to-moderate carbon dioxide levels and submariner decision making. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2018;89:520–5.

Snow S, Boyson AS, Paas KHW, Gough H, King MF, Barlow J, et al. Exploring the physiological, neurophysiological and cognitive performance effects of elevated carbon dioxide concentrations indoors. Build Environ. 2019;156:243–52.

Cronyn PD. Chronic exposure to moderately elevated CO2 during long-duration space flight. 2012.

Jacobson TA, Kler JS, Hernke MT, Braun RK, Meyer KC, Funk WE. Direct human health risks of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide. Nat Sustain. 2019;2:691–701.

Maula H, Hongisto V, Naatula V, Haapakangas A, Koskela H. The effect of low ventilation rate with elevated bioeffluent concentration on work performance, perceived indoor air quality, and health symptoms. Indoor Air. 2017;27:1141–53.

Meadow JF, Altrichter AE, Kembel SW, Kline J, Mhuireach G, Moriyama M, et al. Indoor airborne bacterial communities are influenced by ventilation, occupancy, and outdoor air source. Indoor Air. 2014;24:41–8.

Tang X, Misztal PK, Nazaroff WW, Goldstein AH. Volatile organic compound emissions from humans indoors. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50:12686–94.

Zhang X, Wargocki P, Lian Z, Xie J, Liu J. Responses to human bioeffluents at levels recommended by ventilation standards. Procedia Eng. 2017;205:609–14.

Zhang X, Wargocki P, Lian Z, Thyregod C. Effects of exposure to carbon dioxide and bioeffluents on perceived air quality, self-assessed acute health symptoms, and cognitive performance. Indoor Air. 2017;27:47–64.

Stönner C, Edtbauer A, Williams J. Real-world volatile organic compound emission rates from seated adults and children for use in indoor air studies. Indoor Air. 2018;28:164–72.

Herbig B, Norrefeldt V, Mayer F, Reichherzer A, Lei F, Wargocki P. Effects of increased recirculation air rate and aircraft cabin occupancy on passengers’ health and well-being—results from a randomized controlled trial. Environ Res. 2023;216:114770.

Herbig B, Schneider A, Nowak D. Does office space occupation matter? The role of the number of persons per enclosed office space, psychosocial work characteristics, and environmental satisfaction in the physical and mental health of employees. Indoor Air. 2016;26:755–67.

Arikrishnan S, Roberts AC, Lau WS, Wan MP, Ng BF. Experimental study on the impact of indoor air quality on creativity by serious brick play method. Sci Rep. 2023;13:15488.

Ng E, editor. Designing high-density cities for social and environmental sustainability. London Sterling, Va: Earthscan; 2010. 1 p.

Baum A, Davis GE. Reducing the stress of high-density living: an architectural intervention. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1980;38:471–81.

Abuimara T, O’Brien W, Gunay B. Quantifying the impact of occupants’ spatial distributions on office buildings energy and comfort performance. Energy Build. 2021;233:110695.

Pampati S, Rasberry CN, McConnell L, Timpe Z, Lee S, Spencer P, et al. Ventilation improvement strategies among K–12 public schools—the National School COVID-19 prevention study, United States, February 14–March 27, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:770–5.

ASHRAE. ASHRAE Position Document on Indoor Carbon Dioxide. ASHRAE; 2025.

ASHRAE. ASHRAE Position Document on Indoor Carbon Dioxide. ASHRAE; 2022.

Oke O, Persily A Sensitivity Analysis of CO2 Concentrations as Ventilation Metrics.

Molina C, Jones B, and Persily A. Investigating Uncertainty in the Relationship between Indoor Steady-State CO2 Concentrations and Ventilation Rates. In ASHRAE Topical Conference Proceedings; Atlanta, 2021.

Dedesko S, Mahdavi A, Schweiker M, Vakalis D. The Need for Causal Inference Methods in Indoor Environmental Quality Research. In Kuopio, Finland; 2022.

Chen X, Sun R, Saluz U, Schiavon S, Geyer P. Using causal inference to avoid fallouts in data-driven parametric analysis: A case study in the architecture, engineering, and construction industry. Dev Built Environ. 2024;17:100296.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Parham Azimi, Zahra Keshavarz, Gen Pei, Brian Sousa, Jose Vallarino, and Jiaxuan Xu for their help during this study. We would also like to thank the academic programs at this Boston-based University who participated in this study and helped review and facilitate recruitment and participation of their students.

Funding

Sandra Dedesko was supported by a Postgraduate Scholarship—Doctoral Program from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada; Anna S. Young was supported by the NIEHS T32 ES007069 grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sandra Dedesko: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, software, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. Joseph Pendleton: data curation, methodology, writing—review and editing. Anna S. Young: methodology, software, supervision, writing—reviewing and editing. Brent A Coull: methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing. John D. Spengler: methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing. Joseph G. Allen: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Study ethics approval was obtained from Harvard University’s Human Research Protection Program (IRB protocol IRB21-1243). Signed informed consent was obtained from all participants who enrolled in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Dedesko, S., Pendleton, J., Young, A.S. et al. Associations between indoor air exposures and cognitive test scores among university students in classrooms with increased ventilation rates for COVID-19 risk management. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 35, 661–671 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-025-00770-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-025-00770-6