Abstract

Objective

Identify risk factors of postpartum depressive symptoms (PDS) among preterm infants’ mothers.

Study design

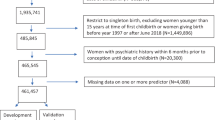

Retrospective cross-sectional analysis of Colorado’s Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System from 2012 to 2018 included weighted n = 33,633 mothers of preterm infants. Multivariate regression models calculated adjusted risk factors of PDS.

Results

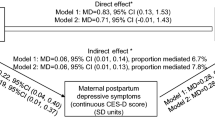

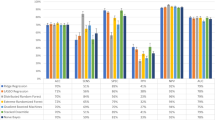

PDS risk factors include history of maternal depression (adjusted risk ratio [aRR] 1.98, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.28–3.05), early preterm birth <34wga (aRR 1.48, 95% CI 1.05–2.08), no prenatal care (aRR 3.19, 95% CI 1.52–6.71), non-Hispanic other (Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaskan, or mixed) race/ethnicity (aRR 1.76, 95% CI 1.10–2.82), and pre-pregnancy public insurance (aRR 2.34, 95% CI 1.46–3.76).

Conclusion

PDS risk factors among Colorado mothers of preterm infants slightly differ from identified risk factors among mothers of term infants. These findings can improve PDS screening and diagnosis so effective therapies and support can be offered during and after NICU hospitalization.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Haight SC, Byatt N, Moore Simas TA, Robbins CL, Ko JY. Recorded diagnoses of depression during delivery hospitalizations in the United States, 2000–2015. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:1216–23.

Bauman BL, Ko JY, Cox S, D xmaned MPH, DV, Warner L, et al. Vital signs: postpartum depressive symptoms and provider discussions about perinatal depression — United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:575–81.

Ko JY. Trends in postpartum depressive symptoms ms and provider discussions about. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6606a1.htm.

Earls MF. The committee on psychosocial aspects of child and family health. incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1032–9.

Stein A, Gath DH, Bucher J, Bond A, Day A, Cooper PJ. The relationship between post-natal depression and mother health interaction. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:46–52.

Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Verdeli H. Offspring of depressed parents: 20 years later. AJP. 2006;163:1001–8.

Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression: an update. Nurs Res. 2001;50:275–85.

Gerstein ED, Njoroge WFM, Paul RA, Smyser CD, Rogers CE. Maternal depression and stress in the neonatal intensive care unit: associations with mother-child interactions at age 5 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58:350–358.e2.

Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1012.

O’hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, Varner MW. Controlled prospective study of postpartum mood disorders: psychological, environmental, and hormonal variables. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:63–73.

O’hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depressiontum mood disorde. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8:37–54.

Bernazzani O, Saucier J-F, David H, Borgeat F. Psychosocial predictors of depressive symptomatology level in postpartum women. J Affect Disord. 1997;46:39–49.

Vigod S, Villegas L, Dennis C-L, Ross L. Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression among women with preterm and low-birth-weight infants: a systematic review: risk of postpartum depression in mothers of preterm and low-birth-weight infants. BJOG. 2010;117:540–50.

Tahirkheli NN, Cherry AS, Tackett AP, McCaffree MA, Gillaspy SR. Postpartum depression on the neonatal intensive care unit: current perspectives. Int J Women’s Health. 2014;6:975–87.

Maternal and Child Health. Pregnancy-related depression and anxiety in Colorado. Maternal and Child Health Program, Prevention Services Division: Colorado Department of Public Health and Epidemiology; 2017. p. 1–5. (Data brief) https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/LPH_MCH_Pregnancy_Related_%20Depression.pdf.

Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Barfield WD, Henderson Z, James A, Howse JL, Iskander J, et al. CDC grand rounds: public health strategies to prevent preterm birth. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:826–30.

Martin JA, Osterman MJK. Describing the Increase in preterm births in the United States, 2014-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2018;312:1–8.

Martin J, Hamilton B, Osterman M, Driscoll A. Births: Final data for 2018. Vol. 68. National Center for Health Statistics; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_13-508.pdf.

Preterm: Colorado, 2008–2018, National Center for Health Statistics, final natality data. Accessed 01 Dec 2020. www.marchofdimes.org/peristats.

Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK, Rossen LM. Births: provisional data for 2018. Vital statistics rapid release. No 7. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2019.

Beck AF, Edwards EM, Horbar JD, Howell EA, McCormick MC, Pursley DM. The color of health: how racism, segregation, and inequality affect the health and well-being of preterm infants and their families. Pediatr Res. 2020;87:227–34.

Shulman HB, D ulmann DV, Harrison L, Smith RA, Warner L. The pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS): overview of design and methodology. Am J Public Health. 2018;108:1305–13.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The patient health questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–92.

Hawes K, McGowan E, O Gowan C M, Tucker R, Vohr B. Social emotional factors increase risk of postpartum depression in mothers of preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2016;179:61–7.

Lee H, Okunev I, Tranby E, Monopoli M. Different levels of associations between medical co-morbidities and preterm birth outcomes among racial/ethnic women enrolled in Medicaid 2014artment of Public Health and. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:33.

Burris HH, Lorch SA, Kirpalani H, Pursley DM, Elovitz MA, Clougherty JE. Racial disparities in preterm birth in USA: a biosensor of physical and social environmental exposures. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104:931–5.

Melville JL, Gavin A, Guo Y, Fan M-Y, Katon WJ. Depressive disorders during pregnancy: prevalence and risk factors in a large urban sample. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1064–70.

Ver Ploeg M, Betson D, National Research Council (US), Panel to evaluate the USDA’s methodology for estimating eligibility and participation for the WIC program. Estimating eligibility and participation for the WIC program: final report. 2003. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10046839.

National Academies Press. Prenatal care: reaching mothers, reaching infants. In: Sarah S. Brown, editor. National Academies Press; 1988. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10062789.

Behrman RE, Butler AS, Institute of Medicine (US), Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. Preterm birth: causes, consequences, and prevention. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2007. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10172661.

Rogers CE, Kidokoro H, Wallendorf M, Inder TE. Identifying mothers of very preterm infants at-risk for postpartum depression and anxiety before discharge. J Perinatol. 2013;33:171–6.

Ko JY, Farr SL, Dietz PM, Robbins CL. Depression and treatment among US pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age, 2005–2009. J Womens Health. 2012;21:830–6.

United States Census Bureau. Detailed race. Colorado, United States: United States Census Bureau; 2021. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=colorado%20versus%20united%20states%20race&y=2018&tid=ACSDT5Y2018.C02003&hidePreview=true.

United States Census Bureau. Race and ethnicity: Colorado & United States, 2018. USA: United States Census Bureau; 2021. https://datausa.io/profile/geo/colorado?compare=united-states#demographics.

Cates CB, Weisleder A, Mendelsohn AL. Mitigating the effects of family poverty on early child development through parenting interventions in primary care. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16:S112–20.

Gonya J, Ray WC, Rumpf RW, Brock G. Investigating skin-to-skin care patterns with extremely preterm infants in the NICU and their effect on early cognitive and communication performance: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e012985.

Samra HA, McGrath JM, Fischer S, Schumacher B, Dutcher J, Hansen J. The NICU parent risk evaluation and engagement model and instrument (PREEMI) for neonates in intensive care units. J Obstet Gynecologic Neonatal Nurs. 2015;44:114–26.

O’Brien K, Bracht M, Macdonell K, McBride T, Robson K, O bsone L, et al. A pilot cohort analytic study of Family Integrated Care in a Canadian neonatal intensive care unit. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:S12.

Cong X, Ludington-Hoe SM, Hussain N, Cusson RM, Walsh S, Vazquez V, et al. Parental oxytocin responses during skin-to-skin contact in pre-term infants. Early Hum Dev. 2015;91:401–6.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment for allowing us to use the Colorado PRAMS data for our research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CT made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, interpreted data for the work, as well as drafted and revised the manuscript. AJ made substantial contributions to the acquisition and analysis of the work and revised the work critically for important intellectual content. SSH made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, interpreted the data for the work and revising the work critically for important intellectual contact. All authors (CT, AJ, and SH) approve this version of the work to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Truong, C., Juhl, A. & Hwang, S.S. Risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms among mothers of Colorado-born preterm infants. J Perinatol 41, 2028–2037 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01088-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01088-5