Abstract

Objective

We compared neonatal (<28 days) mortality rates (NMRs) across disaggregated Asian American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (AANHPI) groups using recent, national data.

Study design

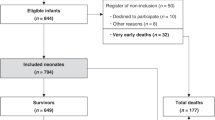

We used 2015–2019 cohort-linked birth-infant death records from the National Vital Statistics System. Our sample included 61,703 neonatal deaths among 18,709,743 births across all racial and ethnic groups. We compared unadjusted NMRs across disaggregated AANHPI groups, then compared NMRs adjusting for maternal sociodemographic, maternal clinical, and neonatal risk factors.

Results

Unadjusted NMRs differed by over 3-fold amongst disaggregated AANHPI groups. Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander neonates in aggregate had the highest fully-adjusted odds of mortality (OR: 1.08 [95% CI: 0.89, 1.31]) compared to non-Hispanic White neonates. Filipino, Asian Indian, and Other Asian neonates experienced significant decreases in odds ratios after adjusting for neonatal risk factors.

Conclusion

Aggregating AANHPI neonates masks large heterogeneity and undermines opportunities to provide targeted care to higher-risk groups.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data for this study is publicly available through the National Vitals Statistics System.

References

Mathews TJ, Driscoll AK. Trends in infant mortality in the United States, 2005–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2017:8.

Ely DM, Driscoll AK. Infant mortality in the United States, 2019: data from the period linked birth/infant death file. Natl. Vital Stat Rep. 2021;70:1–18.

Pabayo R, Cook DM, Harling G, Gunawan A, Rosenquist NA, Muennig P. State-level income inequality and mortality among infants born in the United States 2007–2010: a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1333.

Gillette E, Boardman JP, Calvert C, John J, Stock SJ. Associations between low Apgar scores and mortality by race in the United States: a cohort study of 6,809,653 infants. PLoS Med. 2022;19:e1004040.

Singh GK, Yu SM. Infant mortality in the United States, 1915–2017: large social inequalities have persisted for over a century. Int J MCH AIDS. 2019;8:19–31.

Goldfarb SS, Smith W, Epstein AE, Burrows S, Wingate M. Disparities in prenatal care utilization among U.S. versus foreign-born women with chronic conditions. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19:1263–70.

Hata J, Burke A. A systematic review of racial and ethnic disparities in maternal health outcomes among Asians/Pacific islanders. Asian Pacific Isl Nurs J. 2020;5:139–52.

Holland AT, Palaniappan LP. Problems with the collection and interpretation of Asian-American Health data: omission, aggregation, and extrapolation. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22:397–405.

MacDorman MF. Race and ethnic disparities in fetal mortality, preterm birth, and infant mortality in the United States: an overview. Semin Perinatol. 2011;35:200–8.

Nguyen KH, Lew KP, Trivedi AN. Trends in collection of disaggregated Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander data: opportunities in federal health surveys. Am J Public Health. 2022;112:1429–35.

Gong J, Savitz DA, Stein CR, Engel SM. Maternal ethnicity and pre-eclampsia in New York City, 1995–2003. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26:45–52.

Baker LC, Afendulis CC, Chandra A, McConville S, Phibbs CS, Fuentes-Afflick E. Differences in neonatal mortality among whites and Asian American subgroups: evidence from California. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:69–76.

Qin C, Gould JB. Maternal nativity status and birth outcomes in Asian immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12:798–805.

Cripe SM, O’Brien W, Gelaye B, Williams MA. Maternal morbidity and perinatal outcomes among foreign-born Cambodian, Laotian, and Vietnamese Americans in Washington State, 1993–2006. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13:417–25.

Lee HC, Ramachandran P, Madan A. Morbidity risk at birth for asian indian small for gestational age infants. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:820–2.

Li Q, Keith LG, Kirby RS. Perinatal outcomes among foreign-born and US-Born Chinese Americans, 1995–2000. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12:282–9.

Li Q, Keith LG. The differential association between education and infant mortality by nativity status of Chinese American mothers: a life-course perspective. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:899–908.

Hawley NL, Johnson W, Hart CN, Triche EW, Ching JA, Muasau-Howard B, et al. Gestational weight gain among American Samoan women and its impact on delivery and infant outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:10.

Altman MR, Baer RJ, Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL. Patterns of preterm birth among women of native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander descent. Am J Perinatol. 2019;36:1256–63.

Chang AL, Hurwitz E, Miyamura J, Kaneshiro B, Sentell T. Maternal risk factors and perinatal outcomes among pacific islander groups in Hawaii: a retrospective cohort study using statewide hospital data. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2015;15:239.

Budiman A, Ruiz NG. Asian Americans are the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in the U.S. [Internet]. Pew Research Center. 2021 [cited 7 Nov 2022]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/09/asian-americans-are-the-fastest-growing-racial-or-ethnic-group-in-the-u-s/.

Islam NS, Khan S, Kwon S, Jang D, Ro M, Trinh-Shevrin C. Methodological issues in the collection, analysis, and reporting of granular data in Asian American populations: historical challenges and potential solutions. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:1354–81.

Witzig R. The medicalization of race: scientific legitimization of a flawed social construct. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:675–9.

National Center for Health Statistics. The U.S. Vital Statistics System: a national perspective. In: Vital statistics: summary of a workshop [Internet]. National Academies Press (US); 2009 [cited 5 Aug 2024]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK219884/.

CDC National Center for Health Statistics [Internet]. [cited 2023 Apr 30]. NVSS—Linked Birth and Infant Death Data. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/linked-birth.htm.

Baumeister L, Marchi K, Pearl M, Williams R, Braveman P. The validity of information on “race” and “Hispanic ethnicity” in California birth certificate data. Health Serv Res. 2000;35:869–83.

Mason LR, Nam Y, Kim Y. Validity of infant race/ethnicity from birth certificates in the context of U.S. demographic change. Health Serv Res. 2014;49:249–67.

Balayla J, Azoulay L, Abenhaim HA. Maternal marital status and the risk of stillbirth and infant death: a population-based cohort study on 40 million births in the United States. Women’s Health Issues. 2011;21:361–5.

Huang X, Lee K, Wang MC, Shah NS, Perak AM, Venkatesh KK, et al. Maternal nativity and preterm birth. JAMA Pediatr. 2023;178:65–72.

Kim HJ, Min KB, Jung YJ, Min JY. Disparities in infant mortality by payment source for delivery in the United States. Prev Med. 2021;145:106361.

Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:163–8.

SAS software [computer software], Version 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; Copyright © 2023.

National Center for Health Statistics. Data File Documentations, Birth Cohort Linked Birth/Infant Death, 2002, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Maryland.

Python software [computer software], Version 3.9.13. Python Software Foundation; Released 2022. Available from: https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-3913/.

Seabold S, Perktold J. Statsmodels: econometric and statistical modeling with Python. In: Proceedings of the 9th Python Science Conference. 2010;2010.

Budiman A, Ruiz NG. Key facts about Asian Americans, a diverse and growing population [Internet]. Pew Research Center. 2021 [cited 16 Mar 2023]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/29/key-facts-about-asian-americans/.

Suss R, Mahoney M, Arslanian KJ, Nyhan K, Hawley NL. Pregnancy health and perinatal outcomes among Pacific Islander women in the United States and US Affiliated Pacific Islands: protocol for a scoping review. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0262010.

Bane S, Abrams B, Mujahid M, Ma C, Shariff-Marco S, Main E, et al. Risk factors and pregnancy outcomes vary among Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander individuals giving birth in California. Ann Epidemiol. 2022;76:128–35.e9.

Lee SM, Sie L, Liu J, Profit J, Lee HC. The risk of small for gestational age in very low birth weight infants born to Asian or Pacific Islander mothers in California. J Perinatol. 2020;40:724–31.

Rao AK, Daniels K, El-Sayed YY, Moshesh MK, Caughey AB. Perinatal outcomes among Asian American and Pacific Islander women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:834–8.

Monte L, Shin H. US Census Bureau. 20.6 Million people in the U.S. identify as Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. 2022. [cited 27 April 2023]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/05/aanhpi-population-diverse-geographically-dispersed.html.

Fuentes-Afflick E, Odouli R, Escobar GJ, Stewart AL, Hessol NA. Maternal acculturation and the prenatal care experience. J Women’s Health. 2014;23:688–706.

Gregory ECW, Martin JA, Argov EL, Osterman MJK. Assessing the quality of medical and health data from the 2003 birth certificate revision: results from New York City. Natl Vital- Stat Rep. 2019;68:1–20.

Northam S, Knapp TR. The reliability and validity of birth certificates. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35:3–12.

Gemmill A, Passarella M, Phibbs CS, Main EK, Lorch SA, Kozhimannil KB, et al. Validity of birth certificate data compared with hospital discharge data in reporting maternal morbidity and disparities. Obstet Gynecol. 2024;143:459–62.

CDC Wonder [Internet]. Births Data Summary—Natality 1995–2022. [cited 21 Dec 2023]. Available from: https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/natality.html.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Stanford Center for Asian Health Research and Education for their support of this study.

Funding

Unrestricted funding was provided through the Stanford Center for Asian Health Research and Education and Chi-Li Pao Foundation. This study was also in part supported by funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development R01HD103662, Profit J and Main E, co-PIs; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 1K24HL150476, Palaniappan L, PI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Isabelle Maricar drafted the initial manuscript, coordinated research group meetings, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Santhosh Nadarajah and Risa Akiba drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Daniel Helkey prepared the study’s data, carried out the analyses, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Adrian Bacong, Sheila Razdan, and Latha Palaniappan critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Ciaran Phibbs and Jochen Profit conceptualized and designed the study, supervised the research group and manuscript progress, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was deemed exempt by Institutional Board Review by the Stanford University School of Medicine as data are publicly available and de-identified by the National Vitals Statistics System. Thus, this study was also conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Maricar, I.N.Ý., Helkey, D., Nadarajah, S. et al. Neonatal mortality among disaggregated Asian American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander populations. J Perinatol 45, 1520–1527 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-024-02149-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-024-02149-1